| CARVIEW |

After introductory remarks by Ted Underwood, Matthew Wilkens (Notre Dame) gave a talk (9:20), “Where Was the American Renaissance? Computation, Space, and Literary History in the Civil War Era.” That was followed by a short roundtable on “Digital Collections and the Future of Literary Study” (49:58) that included Harriett Green (English and Digital Humanities Librarian, UIUC) and Wilkens. All the presentations have been archived in a single video, including captions that make the video full-text-searchable.

The Uses of Scale meeting was immediately followed by another (separate but related) conference on “Digital Humanities: Literary Studies and Information Science.”

]]>Schedule

Morning: Discussion among project participants. Room 109, Graduate School for Library and Information Science, 501 E. Daniel St.

9:15 What new opportunities do digital collections and methods open up (for literary study, or for the humanities more generally)? What are the remaining barriers to exploration? What are the barriers to entry for our colleagues and students? (See technical note below.)

11:00 How could institutions in the Humanities Without Walls consortium most effectively coordinate their efforts in this domain, to address the barriers we’ve identified?

12:00 break for lunch

Afternoon: Public events on the 3rd floor of the Levis Faculty Center, 919 W. Illinois St.

1:30 Opening remarks, Ted Underwood.

1:45 – 2:45 Matthew Wilkens, “Where Was the American Renaissance? Computation, Space, and Literary History in the Civil War Era.”

3:00 – 4:15 Digital Collections and the Future of Literary Study: a discussion with Harriett Green, Ted Underwood, Robin Valenza, and Matthew Wilkens.

* * *

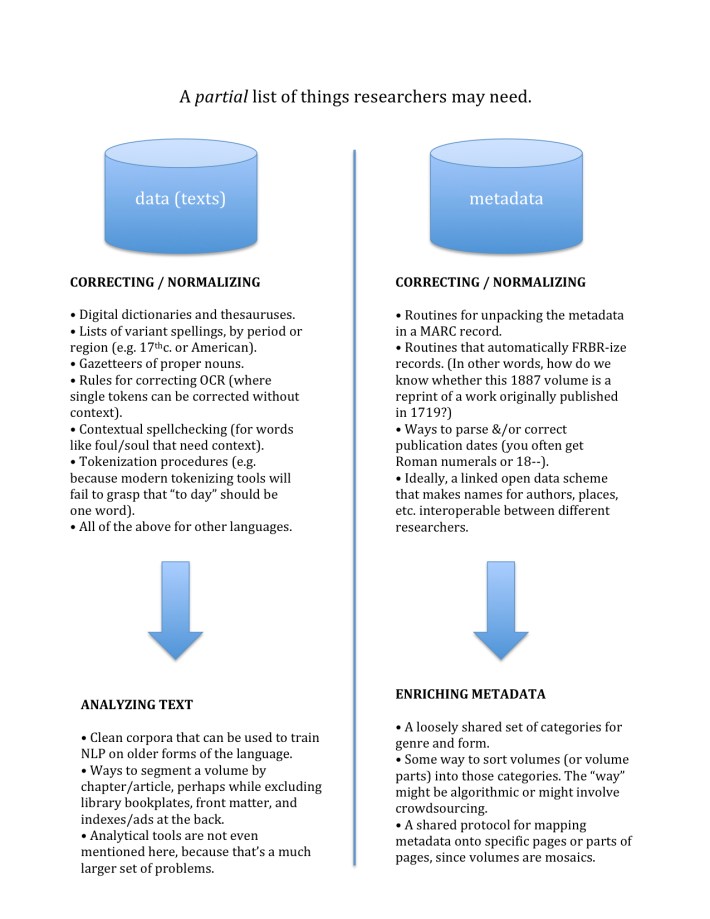

Our goal in this meeting is to frame a flexible discussion that can grapple with a wide range of questions: theoretical, social, and institutional as well as technical. But because the technical obstacles to text mining at scale may be unfamiliar — and tend to form a hazy cloud of minutiae even after they are familiar! — it seemed worthwhile to list some of them in advance. They’re presented below in a very sketchy flowchart. Many important problems are missing here, and some problems listed have already been solved (perhaps in different ways by different research teams). But this at least gives us a place to begin discussion. (Click through for a full-size version, and click again to enlarge.)

]]>We’re hoping Robin Valenza will be able to join us as well. Stay tuned.

This event is free and open to all members of the Notre Dame community.

]]>Once you get to the later nineteenth century, OCR errors may be random enough that they don’t constitute a huge problem for data mining. But before about 1820 they’re shaped by period typography, and are therefore distributed unevenly enough to pose a problem. If you topic-model uncorrected 19c corpora, you get topics containing, e.g., all words with a medial or initial s.

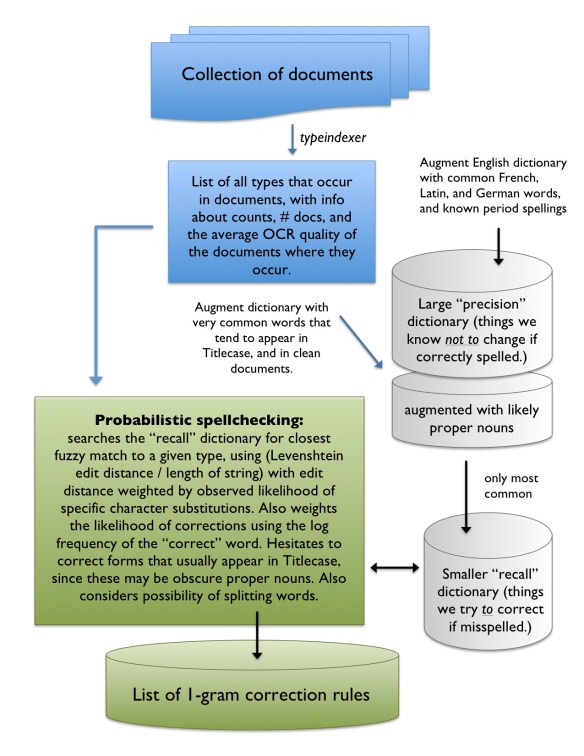

So I’ve been developing a workflow for OCR correction. My goal is not to correct everything, but to correct the most common kinds of errors, especially ones that affect relatively common words (say, the top 50,000 or so).

I’ve borrowed the probabilistic (roughly Bayesian) approach adopted by Lasko and Hauser in this paper for the National Library of Medicine.

- 1. When you hit a token not in the dictionary, search for fuzzy matches in the dictionary.

2. Find the “edit distance” separating the token from each fuzzy match. The edit distance is normally the number of characters that have to be added, deleted, or substituted in order to turn one word into another. But in correcting OCR, some substitutions, like s->f or ct -> d, are much more likely than others, so I weight substitutions by their observed probability in the corpus. The program can learn this as it goes along. The probability of a given correction should also be weighted by the frequency of the “correct” word. E.g., a correction to “than” is more likely than one to “thane.”

3. Decide whether the closest match is close enough to risk making the correction. You have to be cautious correcting short tokens (since there’s not much evidence to go on).

These rules were embodied in a Python script I wrote last year, which worked well enough to make OCR “artefacts” vanish in my analysis of 4,000 volumes. But now that I’m confronting a corpus of 500k volumes, Python is a bit too slow — so I’m rewriting the core of the process in Java. Also, I’ve realized that the scale of the corpus itself gives me certain new kinds of leverage. For instance, you can record the average OCR quality of documents where a given token-type appears, and use that information probabilistically to help decide whether the type is an error needing correction.

I’m now about halfway through designing a workflow to do probabilistic correction on 500,000 HathiTrust documents, and thought I would share my workflow in case people have suggestions or critiques. Click to enlarge.

Two areas where I know people are going to have questions:

1) Why use Titlecase to identify proper nouns? Why not do NLP? The short answer is, I’m mortal and lazy. The longer answer is that there’s a circular problem with NLP and dirty data. With 18c documents, I suspect I may need to do initial cleaning before NLP becomes practical. And since I’m correcting 18/19c books as one gigantic corpus, the 18c habit of titlecasing common nouns isn’t too disruptive. However, this is a place where I would welcome help, if someone happens to have a huge gazetteer of known proper nouns.

2) Why have separate precision and recall dictionaries? In part, this helps avoid improbable corrections. “\vholes” could be an error for the Dickens character Mr. Vholes. But it’s much more likely to be an error for “wholes.” So, while I want to recognize “Vholes” as a valid word, I don’t really want to consider it as a possible “fuzzy match.” You could achieve the same thing with probabilistic weighting, but using a relatively small “fuzzy matching” dictionary also significantly boosts speed, and last year that was an issue. It may be less of an issue now that I’m working in concurrent Java, and running the script on a cluster.

]]>