| CARVIEW |

The post Trouble on the Elwha: Trump’s Budget Cuts Undermine Iconic Salmon Restoration Project appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>Ten distinct runs of salmon and oceangoing trout, including all five North American Pacific salmon species, spawned in the Elwha watershed — until a pair of dams built in the early twentieth century blocked salmon from 90% of the river.

More than a century later, advocacy by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and conservation groups led to the dams’ removal. With the Elwha flowing free again and other habitat restoration in progress, the Olympic Peninsula is regaining its status as a salmon hotspot. Olympic National Park lies at the center.

“Olympic is probably the greatest salmon sanctuary in the national park system outside of Alaska,” says Colin Deverell, acting Northwest regional director for the National Parks Conservation Association. “We’re talking over 3,000 miles of rivers and streams in an area bigger than Rhode Island — most of it wilderness.”

The future of salmon in this vast region is far from assured, however. In fact staff and funding cuts at the National Park Service have jeopardized habitat restoration work in the Elwha and other park watersheds at a crucial time. Olympic Park’s fisheries team has dropped from five staff at the beginning of the second Trump administration to one intern by the start of this year.

“There’s no way one person could possibly fulfill all the responsibilities the national park has toward its fish and communities who rely on healthy fisheries,” says Deverell.

This hollowing out of staff has meant salmon returning to the Elwha go uncounted, hindering work to establish sustainable fisheries. Efforts to end illegal fishing in the Quillayute River are languishing, while a restoration project on the park’s Ozette Lake is in danger of being put on hold. Tribal nations and nonprofits who partner with the Park Service are struggling to fill the gaps.

“The near obliteration of Olympic Park’s fisheries program means it’s all but impossible to do the science that supports restoration work,” Deverell says. “It makes managing fish for people and communities that much harder.”

Staffing Exodus

When Congress passed the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act in 1992, it set in motion a long process meant to restore Elwha salmon to something like their former glory. The law authorized the Department of the Interior to acquire and decommission the river’s Elwha and Glines Canyon dams, a project completed in 2014. This was only the beginning for salmon recovery, however.

The newly freed Elwha transported sediment that had been trapped behind the dams for a century downstream, where it replenished the river delta. Restored river and estuary habitat supported not just returning salmon, but other species from Dungeness crabs to lampreys.

In 2023, for the first time since the dams came down, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe held a ceremonial and subsistence fishery for coho salmon on the Elwha. Supporting treaty-protected Tribal fishing rights is a major objective for salmon recovery. However, setting science-based parameters for fishing requires reliable data about salmon numbers — data the Park Service is best equipped to provide.

“There are now almost no fisheries staff left to do this work,” Deverell says.

The federal hiring freeze of 2025 put seasonal additions to Olympic Park’s fisheries staff on hold. Though the freeze expired in fall, uncertainty over possible future hiring directives from the administration continues to pose challenges. Budget cuts compound the problem.

“The freeze may be technically over, but there’s still very little hiring going on,” Deverell says. “Writ large, the reason comes down to budget issues and personnel directives from the Trump administration.”

Last year Trump’s “Big, Beautiful Bill” cancelled $267 million in funding for staff at the already chronically underfunded Park Service. The departure of all Olympic National Park’s permanent fisheries biologists follows a larger pattern of staff exoduses caused by lack of funding and untenable conditions.

“These are experienced biologists we’re losing,” says Tim McNulty, a board member of Olympic Park Advocates, one of the organizations that pushed for removal of the Elwha dams. “They’re people who have spent years working with the park’s many important salmon streams.”

The void left behind may not be visible to most visitors, but it puts Tribal nations and others who collaborate with the Park Service on fisheries in a difficult situation.

“It’s a predicament, because we share the load of conducting certain salmon and steelhead surveys with the Park Service and Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife,” says Frank Geyer, natural resources director for the Quileute Tribe.

For centuries the Quileute have fished in the Olympic Peninsula’s Quillayute watershed, which includes the Sol Duc, Calawah, and Bogachiel Rivers. The watershed is one of the few places that supports year-round salmon and steelhead fishing, thanks to the Tribe’s sustainable stewardship.

“Going into last fall, we were trying to figure out how to cover work the park would normally do,” Geyer says. “Soon we’ll be starting winter steelhead surveys. If the park doesn’t have staff to help, it’ll be up to the comanagers — Quileute Tribe and WDFW — to cover the gap.”

With basic monitoring of salmon runs barely getting done, many habitat restoration efforts have fallen by the wayside. Most of these projects are far less visible than removal of the Elwha River dams. However, they are part of the same legacy of restoration — one that’s now in danger of faltering.

Struggling Restoration

For the past few summers, Liz Allyn has worked to restore the edges of Olympic National Park’s Ozette Lake, home to a population of Endangered Species Act-listed, genetically distinct sockeye salmon.

Logging near the lake in the 20th century caused erosion that led to sediment building up in the shallows, burying gravel beds where sockeye once made their spawning nests, called redds. Plants took root, further changing the environment in ways that made life harder for salmon.

“Huge areas that used be spawning sites are now covered in native vegetation,” Allyn says. “It’s not an invasive species situation, but it’s a human-caused impact that negatively affects salmon.”

Removing the vegetation would allow sediment to wash away, restoring spawning opportunities. It’s a relatively simple project with big payoffs that is currently being spearheaded by the Makah Tribe with support from the Coast Salmon Partnership, where Allyn works. However, with almost no park resources going toward it, the effort is in danger of collapsing.

“The park has been underfunded for a long time, so their engagement was always limited,” Allyn says. “But in the past, park staff were there to handle permits and certain logistics. Last summer we didn’t even have that.”

Throughout the park similar examples of restoration falling through the cracks amid short staffing abound. In a tributary of the Quinault River, efforts to remove a pile of rubble from a dilapidated bridge that impedes salmon swimming upstream have been delayed. Along the Sol Duc River, Tribal elders can’t access traditional fishing grounds because of a washed-out road.

Even more worrying, there’s often no one on hand when a crisis hits.

Disaster Response

On July 18 a petroleum tanker truck ran off U.S. Highway 101 on the northern Olympic Peninsula, overturning and spilling 3,000 gallons of diesel into a tributary of the Elwha. While the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and Washington’s Department of Ecology rushed to respond, the ability of the Park Service to assist was hamstrung by lack of staff.

Thousands of salmon fingerlings died in the disaster. A more robust initial Park Service response wouldn’t have prevented this, but it could have helped provide vital information as multiple agencies struggled to assess the damage and calculate penalties for the company involved. It’s yet another example of how Trump administration cuts are impeding continued salmon recovery in a dynamic landscape.

At more than 922,600 acres, Olympic National Park is a big place. Ninety-five percent is Congressionally designated wilderness, much of it consisting of steep mountains and valleys. Keeping tabs on salmon throughout such a vast area, let alone outside the park boundaries, is an enormous undertaking that requires deep understanding of the watersheds involved.

When long-time fisheries staff depart, they take years of valuable experience and institutional knowledge with them. This means any new hires will have a lot of catching up to do before they can fill the same roles.

“The decisions we’re making today are built on decades of science that’s given us a picture of how salmon populations are succeeding or failing over time,” Deverell says. “All of that is informed by data from the park. But now we’re at a point where the Park Service can no longer fill that function.”

Previously in The Revelator:

The Monumental Effort to Replant the Klamath River Dam Reservoirs

The post Trouble on the Elwha: Trump’s Budget Cuts Undermine Iconic Salmon Restoration Project appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Animals Are Climate Allies. So Why Are We Leaving Them Out of Climate Policy? appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>It seems we do. Humans.

Over 60,000 penguins off the coast of South Africa, to be more specific.

Through a combination of human-induced climate change and overfishing, we caused sardine populations to collapse. Sardines who are vital for African penguins’ survival.

These penguins normally prepare for a brutal 21-day fasting period, during which they must stay on land to shed and replace their feathers by munching on sardines to build up fat reserves that allow them to survive the fast.

Instead we took their food, and then they starved. More than 60,000 in just eight years.

We’ve pushed them entre la espada y la pared — between a sword and a wall. On one side, a changing climate. On the other, an empty ocean.

And it’s not just penguins.

Late last year a study found that the November floods in Sumatra may have pushed the world’s rarest great apes, Tapanuli orangutans, even closer to extinction. Before the floods fewer than 800 remained in the wild, living in habitats already threatened by industrial activity and growing conflict with humans. According to reporting from Inside Climate News, those floods were “likely exacerbated by widespread deforestation, which stripped the land of its capacity to absorb rainfall and retain soil.” Much of this deforestation was caused by infrastructure development, mining, and palm oil expansion in and around the orangutan’s habitat.

Between causing extreme heat events and making drastic changes to wild habitats, we’re narrowing the safe zone for animals, leaving them with nowhere to go. We may effectively be pushing nearly 80,000 animal species toward extinction in under 80 years.

And yet those same wild animals have a role to play in stabilizing the climate. If we give them a hand.

Wild Animals Are Our Allies

Late last year in Brazil, governments from countries that are parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change met for the 30th time to negotiate a response to the climate crisis — a meeting called COP30.

In the midst of it, at an official event, scientist Dr, Ana Cristina Mendes-Oliveira talked about agoutis, small rodents who live in the Amazon and are responsible for the evolution of Brazil nut trees.

Agoutis, with their sharp teeth and strong jaws, are among the few animals able to crack the nut open. Because one nut can hold up to a couple of dozen seeds, more than a hungry agouti can eat at once, the animals have the habit of burying some of them to snack on another time. They also have the habit of forgetting where they buried them. And so many of those forgotten seeds survive and sprout into impressive trees that can reach heights of up to 160 feet and live for hundreds of years.

Through their hunger and forgetfulness, agoutis enhance carbon sequestration and storage in the Amazon.

Like agoutis, many other wild animals disperse seeds, pollinate, and help cycle nutrients in ecosystems, contributing substantially to the maintenance and restoration of key natural environments.

For example, take the tapir, another forest maker in the Amazon:

-

- They swallow whole fruits and release thousands of seeds in their dung. Many of these seeds belong to species that grow into large, carbon-rich trees.

- Because they travel and drop their waste more often in degraded parts of the forests, they often deliver seeds in spots where regeneration is most needed.

- Since their movements can span miles, they’re long-distance seed dispersers who help connect fragmented habitats.

Beyond these two cases, there are many more, including the American alligator. Studies show that ecosystems with more diverse animal communities are often associated with higher levels of carbon storage and sequestration.

The loss of wild animals in their natural habitats is a problem — not only for them but for our climate, sustainability, and wellbeing.

Animal-Washing No More

At UNFCCC COP30 in Brazil, governments spent two weeks talking about how to confront climate change, including in food systems, in relation to biodiversity loss and desertification, and through adaptation efforts. These issues are inseparable.

And one way or another, animal wellbeing sits at the center of them all.

And yet, despite the walls at the venue being draped with beautiful images of Amazon wildlife, animals themselves barely featured in the negotiations. Mitigation discussions largely sidelined food systems, even though they are responsible for at least a third of global greenhouse gas emissions. And when food systems were discussed, they were discussed without meaningfully addressing the climate, land-use, and biodiversity impacts of industrial animal agriculture or fishing, or what those systems mean for the animals trapped inside of them. Adaptation was debated without recognizing wildlife’s active role in stabilizing ecosystems.

That is animal-washing: celebrating animals in imagery while sidelining them in policy.

This matters not only because animals are on the frontline of the climate crisis, but also because they are ecosystem engineers, essential for effective climate action. Ignoring their contributions in climate policy is a missed opportunity.

Encouragingly, that logic is starting to reach policymakers.

At COP30, Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Environment announced that African leaders had agreed to back a Wildlife for Climate Action Agenda, paving the way for a Global Wildlife for Climate Action Declaration to be launched at COP31. This political commitment was formally endorsed weeks earlier at the African Union Biodiversity Summit in Botswana, where heads of state adopted the Gaborone Declaration on Biodiversity, including a pledge to promote wildlife as part of Africa’s climate response.

In a world that’s pushing penguins, orangutans, and thousands of other species between a sword and a wall, that shift matters.

Because if we stop treating animals as background scenery and start recognizing and protecting them as climate allies, we may yet give both them and ourselves a fighting chance.

Previously in The Revelator:

The post Animals Are Climate Allies. So Why Are We Leaving Them Out of Climate Policy? appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Gator Country’s Climate Guardians appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>In Gainesville the reptiles cluster in places like Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park, but they don’t stay confined there. They make use of the sewer system and sometimes stroll through the city streets.

For my future wife, alligators were simply part of the landscape. For me, with roots in a different part of the world, they were foreign. I’d never seen an alligator up close until adulthood, when I began visiting her in Florida.

The experience was awe-inspiring — and not just because of the reptiles themselves. In Florida I witnessed approaches to large carnivore conservation that reached beyond wilderness and protected areas into shared human landscapes, sustaining populations that remained both demographically and genetically viable.

Alligators teetered on the brink of extinction in the 1950s but recovered thanks to conservation work that took a broad approach: a federal ban on hunting, protection under the Endangered Species Act, wetland preservation, and an innovative management model that combined science, legislation, and local economies.

In Florida today there are about 1.3 million alligators, and altogether in the United States there are about 5 million — from smaller individuals in southern North Carolina to massive beasts in Florida, Louisiana, and eastern Texas.

Millions of people now live close to these big predators, who can weigh around 600 pounds. Around the southeastern U.S. they attract tourists to swamps, so they’re important to the local economy.

One autumn, when my wife and I visited Louisiana, we found ourselves in lush wetlands where heavy Spanish moss hung from cypresses that cast shade over some of the region’s momentarily sleepy alligators. A herd of wild pigs also moved through the swamp.

That surprised us, but what shocked us was seeing wetlands near the bayou drained to make room for suburban housing, asphalt, and concrete. That was hard to understand since Hurricane Katrina had visited the region in 2005 and showed how indispensable wetlands were when the waters rose.

These landscapes are certainly scenic, but they’re also a vital protective infrastructure.

Alligators belong to that infrastructure. Their presence, I learned, shapes wetlands in ways that extend far beyond what meets the eye — including how much carbon these places can keep out of the atmosphere.

Wetlands are among Earth’s richest — and most endangered — ecosystems. Between 60 and 70% of the wetlands that existed in preindustrial times have been wiped out. The wetlands that remain, however, store large amounts of carbon in oxygen-poor soils. When these ecosystems are drained, carbon dioxide is released. Today drained wetlands account for up to 10% of the world’s land-use emissions.

The draining and building we witnessed in Louisiana’s swamps were thus driving human-caused climate change.

But the United States can play an important role regarding wetlands’ significance for climate mitigation: North America harbors 42% of the world’s tidal-influenced wetlands.

Researchers speak of “blue carbon,” the carbon stored in marine biomes and coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, salt marshes, and swamps. These environments are particularly effective carbon sinks because they combine rich vegetation with slow decomposition.

For a long time, science mainly focused on the roles of plants and microorganisms in the carbon cycle. But researchers at Southeastern Louisiana University and the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium wanted to find out what role predators — in this case, alligators — might play. One of the researchers, Christopher Murray, who has worked with alligators for more than two decades, told me in an email, “I believe the value of a single animal can be quantified in terms of carbon stock.”

To test that idea, the researchers analyzed 649 soil samples from wetlands along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, drawing from the Smithsonian’s Coastal Carbon Network. They compared carbon levels in surface soils with maps of alligator distribution and density, focusing on samples collected over recent decades.

The pattern was consistent. Across alligators’ native range, wetlands stored about 0.16 grams more carbon per square centimeter in surface soils when alligators were present. In mangrove forests, the difference rose to roughly 0.20 grams per square centimeter — a trivial amount in a handful of mud, but a substantial gain when multiplied across thousands of square miles of coastline.

Louisiana offered even clearer insight. There, researchers had precise data on nesting patterns and population density. They found that carbon storage increased every time alligator numbers increased. More gators meant more carbon locked into the soil.

How does this work? The answer lies in chain reactions in the ecosystem — the ecological domino effects that occur when top predators influence whole habitats.

Alligators feed, among other things, on herbivorous mammals such as nutria (Myocastor coypus), as well as crabs, fish, and sometimes various kinds of wild pigs. By keeping these populations in check, alligators protect vegetation that would otherwise be trampled or devoured. More plants mean more photosynthesis — and therefore more carbon bound in biomass and soil.

Alligators also function as ecosystem engineers. When they dig dens, move through the muck, or create small pools, sediments and nutrients are redistributed. These processes can create pockets where organic material is preserved for longer.

And the animals can live for 35 to 50 years (or even longer). Their impact accumulates slowly but persistently.

Alligators affect both what is eaten and what the landscape looks like. In short, these enormous reptiles are living regulators of carbon flows, and the predator’s presence enhances nature’s own climate solutions.

The relationship between alligators and carbon storage is strongest in mangrove forests — tropical wetlands where tree roots stretch like braids into the tidal zone.

Mangrove forests are already recognized as outstanding carbon sinks. They store up to 10 times more carbon per acre than an average forest. That alligators can amplify that effect shows how a predator’s presence can improve nature’s own climate solutions.

Researchers have previously found similar patterns in the ocean. Where sea otters (Enhydra lutris) live, kelp forests flourish. But in areas without these predators, kelp forests are decimated by sea urchins (class Echinoidea), and much of the carbon-sequestration capacity is lost.

When top predators return, ecosystems’ structure and function change — including how they store carbon. A British study estimates that reintroducing wolves (Canis lupus) to Scotland — where they could prey upon vegetation-eating deer and other animals and allow woodland to expand — could lead to an additional 1 million tons of CO2 stored per year. Each individual gray wolf is estimated, through its ecological impact, to contribute to the absorption of 6,080 tons of CO2 per year. Each wolf is therefore worth about £154,000 ($202,763), using accepted current valuations of carbon.

In boreal Canada scientists estimate that recovering wolf populations to historical levels could allow forests to store 46 to 99 million additional tons of CO₂ every year — equivalent to the annual emissions of up to 71 million cars.

This new understanding also reveals that predator-control policies have a hidden climate cost. In many regions — from Scandinavia to the U.S. West — large predators are deliberately kept at densities far below what ecosystems can naturally sustain. These decisions are typically justified through concerns about livestock, hunting interests, or culturally ingrained fear. But the climate consequences are rarely counted.

In Sweden undersized predator populations have led to oversized populations of ungulates who consume enormous quantities of young trees, slowing natural forest growth. Forest ecologists estimate that this overgrazing reduces Sweden’s carbon sink potential by about 12 million tons of CO₂ per year. Allowing predator populations to recover to ecologically functional levels could restore roughly half of that capacity — a natural climate gain of about 6 million tons of CO₂ annually.

There are not yet precise figures for alligators’ influence, but the research already suggests that each individual, through its lifelong presence, contributes to increased carbon storage in wetlands.

That biodiversity and climate wins often go hand in hand is an established reality. Protecting top predators is therefore not just about saving species but about preserving an entire ecosystem’s ability to help stabilize the climate.

Conservation should therefore not only be about counting species and their populations, but also about measuring how much CO2 their presence helps to sequester. Nature itself, with its ancient networks and its interplay of life and death and life, shows that everything is intertwined. When balance is found here, it is also found in the atmosphere.

In parts of the Southeast, they have managed to combine climate work with industry. Alligator-related commerce, which partly relies on limited hunting and farming, requires viable wild populations. That means that, on a practical level, the economy favors the conservation of both predators and wetlands.

Generally speaking Americans accept alligators because people feel it’s possible to live with them, control the risks, and even benefit from their presence.

For my wife it was natural to grow up with alligators almost on her doorstep. She knows the folklore and believes that Floridians take pride in them as a natural part of both regional identity and environment. In the primordial creature that is the alligator, culture and nature are united.

Alligators may not care much about this as they go about their lives in the swamps. But these ancient beasts nevertheless do great good, and benefit life on our shared living planet.

Previously in The Revelator:

The post Gator Country’s Climate Guardians appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Rocket Frog, Damselfish, and Bandicoots: The Species Declared Extinct in 2025 appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>This once-common, reef-dwelling fish — described by the Galápagos Conservancy as a “shimmering jewel” — hasn’t been seen since the 1982-1983 El Niño Southern Oscillation, which devastated the ecology around the Galápagos. Fueled by climate change, the weather event brought months of warm water to the normally cooler areas where the fish lived and decreased supplies of the plankton they depended on for food.

By the time weather conditions returned to normal, the damselfish was nowhere to be found.

Divers have spent the past 40 years looking for the fish, to no avail. A 2025 paper published in the Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation concluded that the species should now be considered “likely extinct,” although it encourages ongoing environmental DNA sampling just in case the animal persists.

In a press release about this research, the Conservancy wrote that simply mourning this species is not enough. “Every species lost is a page torn from the book of life. But there’s still time to write a different ending. Let this story move us. Let it motivate us. Because we can still make a difference — if we choose to act.”

Sadly the Galápagos damselfish is not an isolated story. This past year scientists announced many other species we appear to have lost. Their stories are often haunting, but they can motivate us to learn from our mistakes, take advantage of conservation opportunities, and act to prevent further erosions of the natural world.

Here are the stories of the past year, drawn from scientific papers, media reports, and the IUCN Red List.

Christmas Island shrew (Crocidura trichura)

This tiny but loud species — “its distinctive shrill squeaks could be heard all around as one stood quietly in the rainforest,” according to a 2004 species recovery plan — was last seen in 1985, although its final days really began in the first decade of the 20th century, when humans carried rats (and the rats carried diseases) to Christmas Island. That was just the first blow, though. After that came nonnative yellow crazy ants, cats, and other predators. Then came roads, habitat loss, and — finally — the arrival of yet one more nonnative predator, common wolf snakes, in the 1980s. The last two known shrews were found mid-decade; they died soon after, and the species has long been feared extinct. Last year the IUCN calculated the slim possibility of their continued survival and made it official.

The 52-square-mile Christmas Island — a territory of Australia — may not be very big, but it looms large in the extinction crisis. Isolated from other land masses by hundreds of miles of ocean, dozens of unique species had the opportunity to evolve there. That worked just fine until humans arrived and knocked the delicate system out of whack. This shrew is at least the fourth extinction of the island’s unique species. Let’s hope it’s the last.

Mimo jiaoyue

A paper published in February 2025 described this freshwater mussel for the first time … and declared its possible extinction. The authors based its name on “an ancient Chinese term for the moon, used to describe the shell’s shape as being as round as the bright moon in the night sky.” The species was native to Lake Fuxian in China, but the paper points out that the lake is highly polluted, with low levels of dissolved oxygen, and the shoreline has been destroyed by development. The paper reports that no living specimens have been found and pollution levels suggest it’s “highly unlikely that any surviving populations remain.” (A 2021 paper identified a host of threats to this lake, including “rural domestic pollution, farmland runoff pollution, urban domestic pollution, phosphorous chemical pollution, and tourism pollution.”)

And this species may not have been the only one to disappear from the lake: Freshwater mussels rely on specific fish species to host their larvae, and the authors suggest that M. jiaoyue’s unidentified host species may have also gone extinct.

Dryadobates erythropus

Sometimes we find evidence of extinction not in the wild but in museums or other scientific collections. That’s the case with this 14-millimeter (.55 inches) frog, described by researchers as a new species based on a “badly desiccated and extremely fragile” specimen that had been collected by pioneering herpetologist Doris Cochran in Brazil in 1963 (and stored at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, ever since).

The authors noted that the site where the original specimen was collected “has been transformed into a highly developed residential and commercial area lacking suitable habitat,” so it seems unlikely the frog persists in the wild.

Like other so-called “rocket frogs,” this species had a thin, streamlined body, a pointed face, and probably the ability to leap many times its body length. Too bad they couldn’t jump out of the way of humanity.

Ngutu kākā (Clianthus puniceus)

This shrub with delightful red flower clusters hails from New Zealand’s North Island, where it hasn’t been seen in the wild since 2015, although it still exists in a handful of herbariums. The reasons for its disappearance remain unclear, but it seems likely to have fallen prey to nonnative herbivores such as feral goats, red deer, and snails. Extensive surveys have failed to turn up any free-growing populations, so the IUCN this year assessed the plant as “extinct in the wild.”

A related species, C. maximus, persists in the wild — barely — with about 150 known plants (a number New Zealand’s Department of Conservation is actively working to increase). Both species are collectively known as “Kākābeak” because their flowers are shaped like the beak of the kākā parrot (Nestor meridionalis).

Slender-billed curlew (Numenius tenuirostris)

This once-wide-ranging bird led our annual extinction list in 2024 after a scientific paper declared it lost due to overhunting and habitat loss. This year the IUCN used the paper as the basis for wider scientific consensus and similarly listed the species as extinct.

Eugenia acutissima

This Cuban plant hasn’t been seen since 1952 and probably fell victim to agricultural development; it was only observed by scientists once. In 2025 the IUCN declared it extinct.

Delissea sinuata

Native to the Waianae Mountains of Oʻahu, this plant hasn’t been seen since 1937. Nonnative species have heavily degraded its former habitat — another example of why Hawai‘i is often referred to as the “extinction capital of the world.” It would be easy to spot if it still existed, because it grew up to four feet high and bore striking purple berries.

Diospyros angulata

Proof that science takes its time: This plant from the island of Mauritius (home of the infamously extinct dodo) was last seen in 1851. The IUCN finally published an assessment identifying the species as extinct in 2025. The likely causes of its extinction include logging, grazing, soil erosion, and competition from nonnative plants and animals.

Syzygium ampliflorum

This tree grew on an active volcano — Mount Galunggung in Java, Indonesia — which last erupted over a nine-month period beginning Oct. 8, 1982. The eruption killed 2,000 people, wiped out 88 villages, and presumably caused this plant’s extinction — that is, if it hadn’t already been killed off during earlier eruptions in 1894 and 1918. An expedition in January 2025 failed to turn up signs of this plant’s existence, and a paper published in September suggested it should now be considered possibly extinct. If so, that would make it one of the few extinctions on this list not directly linked to human activity.

This small, flowering herb from New Caledonia was only documented twice, in 1967 and 1968. Its only habitat has suffered from frequent fires and grazing from nonnative Rusa deer. The IUCN assessed it as extinct in 2022 but only published that in 2025.

Another rarely documented New Caledonian herb — Pytinicarpa tonitrui — faced the same threats and has also been declared extinct.

Kākāpō parasites

New Zealand’s critically endangered kākāpō parrots (one of our species to watch in 2026) nearly went extinct a few decades ago. Conservationists saved the species by moving the last of these flightless birds to safe, predator-free islands. They’ve been doing fairly well ever since and may experience a baby boom in the year ahead, but they’ve lost something else along the way: their parasites. A study published this past July found more than 80% of the parasite species previously associated with kākāpō prior to the 1990s have disappeared. Of the 16 parasites the researchers identified, only three remain on the birds.

The paper suggests that four of these parasites were associated exclusively with kākāpō and, with no other species to host them, have gone extinct.

This might seem like a “no big whoop” deal, but parasites rarely deserve their bad reputation. They often play important ecological roles — research suggests they can help keep our immune systems healthy and may even protect us from any new, potentially more destructive parasites that arrive.

Their disappearance, meanwhile, is a sign that natural systems are deeply disturbed — and if a habitat can’t support a parasite, what does that mean for the fate of the host species?

A press release about this research gives us further food for thought. It reminds us that parasites live on a small proportion of the population of their host species, so when the bigger species become endangered, the parasites are likely to go extinct faster than the hosts (a process called secondary extinction or coextinction). This means parasite declines could be considered an early warning system and tip us off to problems in the hosts.

At the same time, the paper warns that we may have underestimated the rate of parasite extinction worldwide and failed to account for them in our documentation of disappearing species. Case in point: What if every extinction announced this year also involved the extinction of one or two parasite species?

So let’s spare a moment to think about these lost species — and maybe give those that remain a little extra attention and appreciation.

Madeiran large white (Pieris wollastoni)

This striking, 2-inch butterfly once flew in Madeira, an autonomous region of Portugal, but hasn’t been seen since 1986. The IUCN SSC Butterfly Specialist Group assessed it as extinct in 2023, but that wasn’t published to the IUCN Red List until last year. The cause of its extinction remains unclear, but possible factors include pesticides, a virus, or the decline of the plants the butterflies’ larvae depended on.

Conus lugubris

This poor little cone snail was once abundant on the Cape Verde Islands, which have since become a tourist mecca. Rapid coastal development since the late 1980s has destroyed the snails’ habitat and the species is now presumed extinct.

Leptaxis vetusta

This Portuguese land snail was scientifically described in 1857 based on a fossil shell and has never been observed alive. The IUCN this past year assessed it as extinct.

Mastigodiaptomus galapagoensis

This small copepod (a type of crustacean) lived until recently in El Junco, a high-elevation freshwater crater lake on San Cristóbal island in the Galápagos that has no naturally occurring fish. An illegal attempt to establish a tilapia fishery there in 2005 or 2006 devastated the lake’s ecology. By the time efforts to eradicate the nonnative fish began in 2008, the lake held an estimated 40,000 tilapia. Native invertebrates didn’t stand a chance. A paper published in 2021 suggested this had caused an extinction; the IUCN this year gave broader consensus to that sad reality.

Snowy owls (Bubo scandiacus) in Sweden

Sometimes species disappear on the regional level, which is known as extirpation rather than extinction. This year the conservation organization BirdLife declared snowy owls regionally extinct in Sweden, a decade after the last sign of the birds breeding in that country.

BirdLife says this should serve as a warning for all northern countries in which snowy owls still roam, where climate change is rapidly altering ecosystems and making them less hospitable to these iconic birds (and so many other species in the process).

Thaumastus teixeirensis

Another land snail, this time from Brazil. Scientists have previously identified dozens of other species in this genus, but this one slipped by until a paper published this past year. Evidence of the species emerged from sambaquis — shell mounds left as monuments by prehistoric people. Researchers found the shells for this new species in these mounds and wrote that “efforts to find similar living specimens, or even empty shells, in that region were fruitless, strongly suggesting that the species is currently extinct.”

Acropora corals

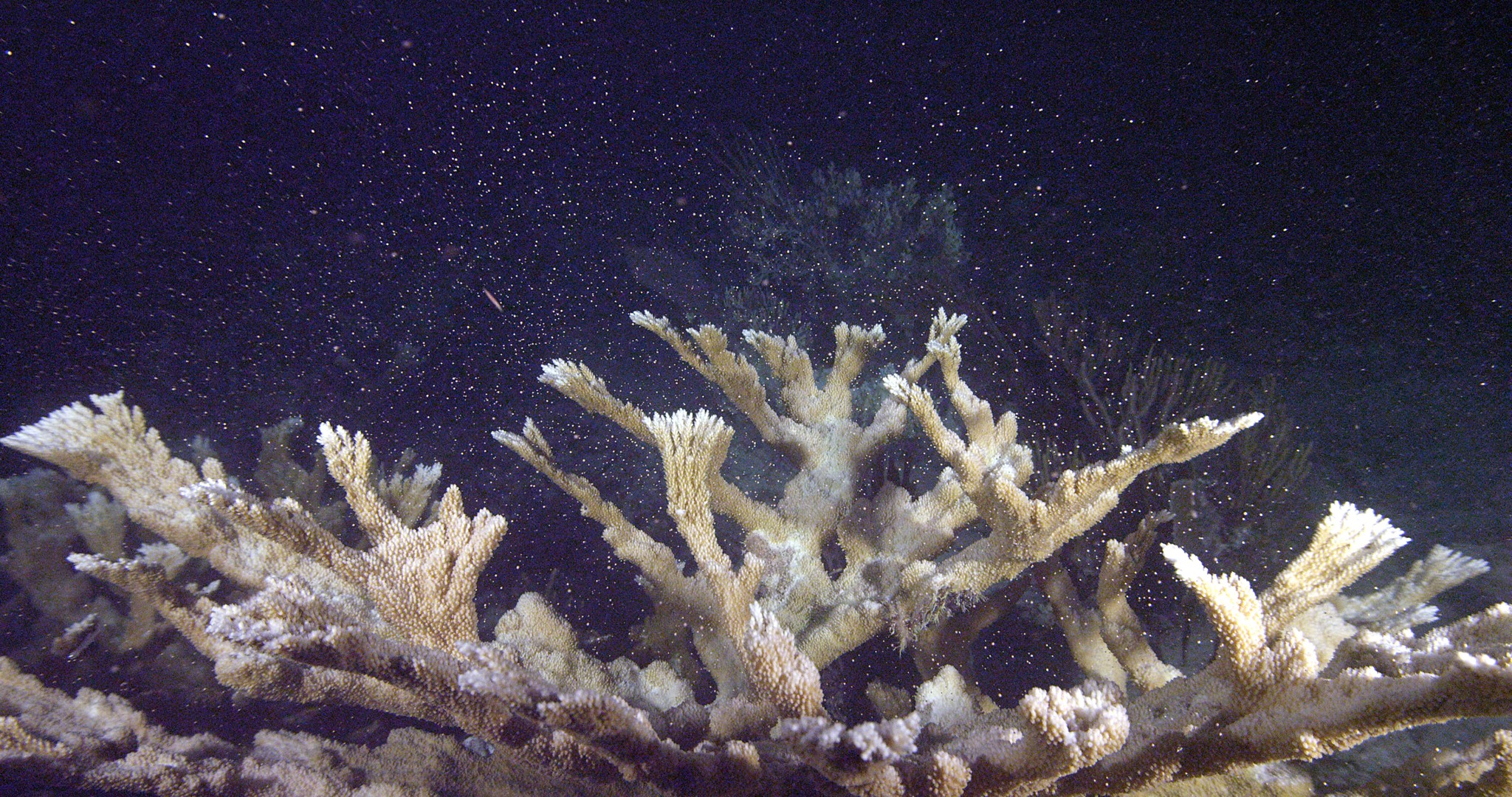

Not an extinction, and not an extirpation, but about as close as you can get: A paper published this past October warned that an “acute heating event” along the Florida Keys in 2023 killed between 97.8% and 100% of elkhorn (Acropora palmata) and staghorn (A. cervicornis) coral colonies. So many corals died that further reproduction remains unlikely, leaving the species in this area “functionally extinct.” This is climate change in a nutshell, folks.

Several Italian plant species

A massive study of the vascular plants of Italy (i.e., most plants other than mosses and the like) reassessed 628 species, resulting in conservation status updates for 44% of them. The 100-plus authors fanned out across the country and found that the fate of 57 species has improved. But they also found that 176 species fared worse than their previous assessments, and the researchers confirmed several regional and national extinctions, mostly in aquatic habitats.

Among the losses:

-

- Atriplex mollis in Sardegna

- Coleanthus subtilis in Trentino-Alto Adige

- Taraxacum pauckertianum in Toscana

- Aldrovanda vesiculosa all over Italy

- Mentha cervina in Abruzzo

- Nuphar lutea and Nymphaea alba in Sicilia

- Utricularia minor and vulgaris in Toscana

- Potamogeton gramineus and Sonchus palustris in Veneto

- Crucianella maritima in Calabria

- Juniperus sabina in the Marche

Other countries would do well to follow the lead of these Italian botanists. As they write in the paper, “This research also underscores the importance of botanical collections and historical records to reconstruct the history, dynamics, and current distribution of plant species, and addresses challenges such as limited access to the collections. This study is not only a milestone in Italian floristics but also provides a replicable methodology for updating national floras globally.”

Six bandicoots

These long-unseen (and in some cases newly identified) Australian marsupials got their first — and last —entries on the IUCN Red List this past year when all were listed as extinct species:

-

- Northern pig-footed bandicoot or Yirratji (Chaeropus yirratji) and southern pig-footed bandicoot (C. ecaudatus) — Previously considered one species, they were reassessed as two species in 2019 using a combination of fossil records, Aboriginal oral accounts, bones, and taxidermied specimens. Unseen since the 1950s and 1930s, respectively, the two bandicoots probably disappeared due to introduced predators (like cats and foxes), changes in fire regimes instituted by European settlers, and habitat degradation by livestock. The rest of the bandicoots on this list faced similar stories.

- Nullarbor barred or butterfly bandicoot (Perameles papillon) — Last seen alive in 1928 and identified as their own species in 2018 based on museum specimens. The only known photos of this species were rediscovered in 2025.

- South-eastern striped or southern barred bandicoot (Perameles notina) — Last seen in the mid-19th century.

- Liverpool Plains striped bandicoot (Perameles fasciata) and southwestern barred bandicoot or Marl (P. myosuros) — Previously considered subspecies, these bandicoots were elevated to full species status in research published in 2018. They were last seen in 1846 and 1907, respectively, and cats once again get the blame for most of their declines.

Three Caribbean lizards

A recent study took a deep dive into the DNA of forest lizards from the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, and Hispaniola and shook things up quite a bit, ultimately defining 35 new species — including one that lives near Goldeneye, Jamaica, where author Ian Fleming wrote his James Bond novels (they of course named the species Celestus jamesbondi). In the process they declared the Altagracia giant forest lizard (Caribicus anelpistus) and yellow giant forest lizard (Celestus occiduus) “critically endangered (possibly extinct)” (assessments already made by the IUCN Red List under different common names) and added a newly identified species, the black giant forest lizard (Celestus macrolepis), to the list of lost species.

Armeria maritima

An odd case to wrap up this list: Botanists considered this species “extinct in the wild,” with the last living samples growing at Utrecht University Botanic Gardens in the Netherlands. But recent DNA tests of the living plant and 19th-century specimens showed that the gardens actually held a hybrid of two different Armeria species. That allowed them to declare that Armeria arcuate is truly extinct — but at the same time it illustrated the value of botanical gardens and herbarium collections, which can still provide critical scientific evidence even if the samples are decades or centuries old. Many herbarium collections themselves face extinction in an age of scientific budget cuts, so that’s an important message we’d do well to take to heart.

Previously in The Revelator:

The Curlew, the Cactus, and the Obliterated Whitefish: The Species We Lost in 2024

The post Rocket Frog, Damselfish, and Bandicoots: The Species Declared Extinct in 2025 appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Protect This Place: Elijio Panti National Park, a Mayan Heritage Site in the Heart of Belize’s Rainforest appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>We’re in Noj Kaax Meen Elijio Panti National Park, a protected area situated in the heart of the Maya Mountains in western Belize, near the border with Guatemala. Bounded by the Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve and the Macal River, it’s an extremely biodiverse, tropical rainforest with some remaining intact areas of primary broadleaf forest.

Why It Matters:

Named after the world-renowned traditional Mayan healer Don Elijio Panti, Noj Kaax Meen (which means “canopied rainforest of healers”) Elijio Panti National Park is home to some of the most emblematic and endangered wildlife of the Neotropics, including jaguars, spider monkeys, tapirs, and scarlet macaws. It also conceals several large, intricate caves full of artifacts and relics where the ancient Mayas conducted rituals and ceremonies. Some of these caves remain unexplored.

The Mayas’ descendants still live here. They consider the land, rivers, trees, herbs, birds, jaguars, and other wildlife to be their heritage, which they are honored to take care of. They’re dedicated to preserving the delicate balance between the territory and the people. The legacy that Don Elijio Panti, a spiritual leader as well as a healer, left within the national park is also paramount for this community, as he offered ceremonies of gratitude to the spirits and the land, meditated, and gathered sacred herbs to serve his people.

The park is full of economically important trees, such as mahogany, nargusta, rosewood, sapodilla and ceiba, which supply food for many insects, birds, and mammals. They’re also important habitat: In their massive crowns and branches, you can find nests of top predators such as the stunning ornate hawk-eagle or the black-and-white owl.

At the same time, as if these trees represent a duality of blessing and curse, they attract national and international logging companies, eager to cut them down and extract their precious timber at any cost.

The Threat:

Last July the government granted a logging license to Belize Woodmark Designs Ltd., allowing the furniture company to harvest wood in approximately 11,500 acres of the area known as the Western Hardwoods. The area is situated within the Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve and directly borders Elijio Panti National Park to the south. According to park head ranger Rigoberto Saqui, this logging concession will severely harm ecological connectivity and populations of mammals with large home ranges like jaguars and tapirs.

“It’s a ripple effect that happens when a logging concession begins in an area,” he says. “When new roads are opened, it makes it easier and accessible for other loggers, looters, or poachers to do illegal activities within the park.”

He also mentions a consequence that would reach areas even beyond the park.

“The Western Hardwoods are very sensitive when it comes to its ecological functioning: It has a lot of headwaters that flow into the major tributaries of Belize.” This means the effects of the operation would stretch into areas and communities far away from the park through damage done by logging to water quality.

The license was granted for 30 years, with the option to be extended for an additional 30, and was granted despite the opposition of the chief of the Forest Office Department.

My Place in This Place:

I visited Elijio Panti National Park for the first time last summer, leading a group of college students in environmental sciences from the United States. As an ecologist and passionate naturalist, I immediately connected with the exuberant jungle and spent the days walking trails up and down, checking jaguar and tapir tracks, birdwatching, swimming in the beautiful waterfalls, exploring deep caves, and learning nonstop from the park rangers who accompanied us.

I felt privileged to witness such a vibrant landscape, and I also observed my students’ constant enthusiasm in discovering the rainforest for the first time, opening their eyes to a new world full of unique species, sounds, and scents.

When the rangers told me about the ongoing situation with the logging concession, I felt powerless in the face of corporate interests that care nothing about the needs of nature and the people, so I decided to do my part and share the voice of the park and its community. I will continue to bring my students to Elijio Panti every year, so they can learn about rainforest ecology, its brimming wildlife, and the endless challenges human greed poses to the common good.

Who’s Protecting It Now:

The Itzamna Society has co-managed the park with the state since 2001. A team of four brave rangers patrols about 16,000 acres (roughly 9,000 football fields) of hilly terrain. They have been navigating the dense rainforest and working to control groups of illegal poachers, loggers, and looters with the help of two motorbikes, machetes for opening small trails, their strong legs, and determined hearts.

What This Place Needs:

In the words of the head ranger Rigoberto Saqui, “The number of rangers that we have — it’s not enough, and we have seen the consequences of our limited capacity to safeguard the park.”

The park requires more personnel to initiate proper long-term research and be more efficient in patrolling and protecting the area. It’s crucial to initiate research to identify key sites within the park that may contain hidden Maya caves before looters arrive. There’s also a significant chance that the park holds new-to-science species of insects, plants, and other groups, which means that the community and rangers need equipment and training to start monitoring and collecting data.

The rangers also need to acquire fire-extinguishing equipment, since the dry season is about to start and they have had difficult experiences in the past trying to fight wildfires with minimal tools. The government does not have either the initiative or the capacity to provide help in these situations.

The Itzamna Society is trying to secure a large grant that will allow it to implement several processes to better address the park’s needs, but the team is struggling to write the proposal due to a lack of grant-writing expertise. If anyone reading this article has experience with grant-writing for conservation or environmental causes and is willing to help, please contact me so I can connect you with the team.

Lessons From the Fight:

The oppression carried out by companies and corporations to destroy the last wild places on this planet for mere profit and personal convenience can’t be allowed anymore. It’s clear that we can’t trust governments to take care of mountains, rivers, and forests, so what are our options as citizens?

Elijio Panti National Park and the Itzamna Society are a clear example of the power of communities in protecting nature. This Mayan community will defend their place with their lives as long as they exist, because it’s part of their identity and legacy.

Similarly, rebuilding our relationship with nature is a duty we have as humans, so we’re intrinsically motivated and ready to do whatever’s necessary to safeguard the sources of food, clean water, and clean air for ourselves and the rest of the fellow creatures with whom we share the world. Most of Western society has lost our connection to our territories, allowing private interests to extract the land’s wealth without resistance.

Lastly, one of our greatest powers as citizens comes from our ability to make informed choices as consumers. What would happen if no one bought any furniture from the company that received the logging concession that now threatens Elijio Panti National Park — or other exploitative companies?

Follow the Fight:

Follow the Itzamna Society, the local community and co-managers of Elijio Panti National Park, on Facebook.

And visit the park’s own website, where you can find detailed information on this unique protected area.

Share your stories:

Do you live in or near a threatened habitat or community, or have you worked to study or protect endangered wildlife? You’re invited to share your stories in our ongoing features, Protect This Place and Save This Species.

Previously in The Revelator:

The post Protect This Place: Elijio Panti National Park, a Mayan Heritage Site in the Heart of Belize’s Rainforest appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Incredible Journeys: Filling in the Blanks of Sea Turtle Migrations appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>Recent studies are giving scientists a better understanding of migrations at the species and population levels and reveal implications for conservation. This series focuses on a few particular species, what we’re learning about their migrations, and how that knowledge may help us protect them.

This second installment in the series looks at a group of reptiles who really get around: sea turtles.

Sea turtles live complex lives that have mostly gone unstudied and unobserved by human researchers. But new technology, including lightweight satellite transmitters as small as a thumb drive, is increasing the ability of scientists to tag and track the turtles at every stage of their development. The resulting data have upended several major assumptions and revealed details of the movements of these highly migratory marine reptiles — details that could support efforts to protect them.

“If you look at their life cycle, sea turtles occupy the entire oceanic realm,” says Pam Plotkin, a retired Texas A&M University Department of Oceanography professor. “They’re in bays and estuaries, on beaches, near shore, and out in the high seas. And threats exist in all those areas.”

Sea turtles nest on beaches, and hatchlings move to nursery areas over waters deeper than about 650 feet (200 meters). Scientists long believed the young turtles passively drifted with ocean currents for four to six years, but didn’t know much about this oceanic stage, calling it the “lost years.”

They also assumed that after the animals returned to coastal waters as larger juveniles, they remained there through adulthood, with seasonal migrations to foraging areas and nesting beaches.

But those assumptions weren’t entirely accurate.

“The more tags we put out, the more we saw turtles doing things we weren’t expecting,” says Kate Mansfield, a professor at the University of Central Florida Marine Turtle Research Group, who started satellite-tracking animals more than 12 years ago during their post-hatchling period (after they leave their natal beaches for the open ocean). “It was our first inkling that there’s more nuance to it.”

The first unexpected discovery was that post-hatchlings are active swimmers, confirmed by research on oceanic-stage loggerheads (Caretta caretta) and green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the North Atlantic and juveniles of different species tagged in the Gulf.

Tracking also showed that not all adults migrate predictably to foraging areas and nesting beaches.

For example, juvenile loggerheads spend their summers in Chesapeake Bay before heading south to warm Gulf Stream waters in fall. But about a third to a quarter of those tracked went far offshore, some for a long time.

“We started questioning the model that once they check the box on the oceanic stage, they move into coastal habitat and remain the rest of their lives,” Mansfield says. “That has big implications for understanding where and when these animals are and the threats they may encounter.”

Those peripatetic loggerheads, for example, pass through coastal and longline fishery areas.

Olive Ridleys

Research that Plotkin started in 1990 upended another truism, this one about olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea), who practice mass nesting events called arribadas.

Plotkin expected to track throngs of them migrating between a Costa Rican arribada beach and a feeding ground somewhere in the eastern Pacific Ocean. That would have made it relatively easy to protect their route between the two.

But the data showed olive ridleys swim hundreds to thousands of miles from their nesting beach, taking different and unpredictable routes among multiple areas that vary one year to the next. Not so easy to protect.

In addition, conservation efforts had focused on protecting known arribada beaches in Mexico and Costa Rica, but it turned out that many olive ridleys nest alone on beaches from Mexico to Ecuador.

“The idea had persisted that solitary nesters just missed the arribada, didn’t get the memo,” Plotkin says. “But there are hundreds of thousands of them, and they are widely distributed.”

Olive ridleys are classified as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. The most recent status report on this species, to which Plotkin contributed, noted significant declines on many solitary nesting beaches, highlighting the need to protect those sites as well.

Green Sea Turtles

The IUCN Red List recently reclassified green turtles from Endangered to Least Concern, noting that the population has increased by 28% since the 1970s. This positive milestone reflects international, long-term conservation and protection of nesting beaches and marine habitats, guided by a lot of research.

Green sea turtles nest in significant numbers on the Florida and Texas Gulf coasts. As Mansfield’s research showed, after years in the open ocean after hatching, as small juveniles they move to nearshore seagrass beds, reefs, and lagoons.

Ryan Welsh, a senior scientist at the Inwater Research Group, says larger juveniles then go to areas like the Florida Keys, where deeper waters near seagrass beds help them avoid predators as they mature into adults. In 2022 he and Mansfield found one of the world’s densest green sea turtle foraging aggregations near Key West, in an area called the Eastern Quicksands. An estimated 3,000 animals, ranging from 150 to 500 pounds, occupied 18 to 22 square miles (30 to 36 square km).

“This is unique in the density of animals, especially big animals,” says Welsh.

The Eastern Quicksands are under jurisdiction of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, providing some protection for the turtles and seagrasses. But Welsh recommends further protecting the area with Endangered Species Act critical habitat designation.

“Adults are especially vulnerable,” he says. “As they migrate to nesting beaches in Costa Rica, Mexico, and the eastern U.S., they’re exposed to a lot of risks and enter areas where they might not be protected. Giving them the best protection we can where they spend the majority of their time is critical and the least we can do.”

In July 2023 NOAA published a proposed rule to designate critical habitat for green sea turtles that included the Quicksands and other areas. But it remains just a proposal.

The Quicksands are the site of a lot of fishing activity for Caribbean spiny lobster and Florida stone crab, and those nets can entangle sea turtles. Welsh would like to see the sanctuary prohibit or limit fishing there. A series of meetings with multiple stakeholders proposed creating a Marquesas Keys Turtle Wildlife Management Area, he says, but the Florida governor vetoed it.

Other Protections

It takes more than protected areas to help these highly mobile reptiles, though.

Incidental capture by fisheries is a common threat, including from bottom trawlers, which tow a net along the ocean floor to capture target species such as shrimp. A 2021 paper in Nature reported that trawlers scrape some 1.9 million square miles each year.

Turtle excluder devices, or TEDs, have reduced capture of sea turtles by bottom trawlers in the United States, according to Plotkin. A TED is a grid of bars in the neck of the net and an opening in the net’s top or bottom. Small shrimp pass through the bars and into the net while larger animals, such as sea turtles, are stopped by the bars and escape through the opening. A recent NOAA pilot project showed that narrower bar spacing reduced bycatch of juvenile sea turtles, which could slip through standard bars, without significantly decreasing shrimp catch.

Texas Sea Grant, where Plotkin previously served as director, was instrumental in developing these devices and gaining their acceptance among Gulf of Mexico shrimpers. But the U.S. currently requires TEDS only in shrimp and summer flounder trawl fisheries. Other countries don’t always require them or enforce their use.

“Catch remains a significant problem for sea turtles,” Plotkin says. “And trawlers operating near nesting grounds or foraging grounds can do a lot of damage.”

Pelagic or deep-sea longline fisheries, which set out baited hooks at various depths that often remain in place for hours, are another threat. Sea turtles can swallow hooks, be hooked in the flippers or head, or become entangled in longlines and drown.

Sea turtles are less likely to swallow circle hooks and can more easily escape this type of gear. Other techniques to reduce bycatch include changing baits, minimizing how long lines are in the water, and limiting mainline length. But these methods are not used everywhere, Plotkin says.

Other options are moving fisheries to areas less frequented by sea turtles and closing areas at certain times to accommodate their migrations.

Those measures require ongoing research to better identify those areas.

“Just a handful of tags opened our eyes to how complex the picture is,” Mansfield says. “We have holes to fill in. A lot of our work is in the North Atlantic and we need similar work elsewhere.”

More research also is needed on the role of temperature on migration and other behaviors. Sea turtles are ectotherms (what we used to call “cold-blooded”) and cannot regulate their body temperatures, which means water temperatures affect their bodies and behavior. In addition, sex is determined by the temperatures that eggs are exposed to in the nest, with higher temperatures producing females. Changing temperatures therefore could shift sea turtle sex ratios as well as nesting and foraging habitats, according to scientists at the Université libre de Bruxelles in Belgium. They predict the disappearance of 50% of current known sea turtle hotspots by 2050.

The lengthy sea turtle life cycle is another reason for ongoing study.

“Even when we see upticks in nesting, as we have with greens, that needs to be maintained for a long time before it represents a solid recovery,” Mansfield says. “You can’t just take a good year here and there, it takes generations. Bottom line, we need to learn more about where these animals are going and what they are doing there.”

Previously in The Revelator:

The post Incredible Journeys: Filling in the Blanks of Sea Turtle Migrations appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Photo Essay: Climate Change and Deforestation Collide in Indonesia’s Deadly Floods appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>“I lost my husband, and our house is damaged and filled with mud,” says Siti Basmallah, of Babo village in Aceh Tamiang Regency.

“I saw the flood reach 15 meters [50 feet] above our houses,” Siti says. “Villages turned into rivers and homes were destroyed.”

The damage has made it difficult for response teams to reach villages and deliver aid, worsening suffering.

Amid views of damaged homes and debris in Aceh Tamiang, Syahrial Umar says the community urgently needs clean water and food.

“Our settlement was destroyed, as if by a tsunami,” he says. “Many victims remain missing.”

Logs, swept along by deadly flash floods, became destructive battering rams as waters carried them into communities.

“I saw many logs carried away by the flood,” Syahrial says. “They came from upstream, likely due to logging.”

This destruction, extreme weather, and heavy and unpredictable rainfall are signs that the impacts of the climate crisis are real, says experts. Indonesia’s Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency classified the Senyar cyclone an unusual phenomenon.

Widespread deforestation has made the effects of climate change worse in Indonesia. According to a Greenpeace report, based on data from the Ministry of Forestry for the period 1990-2024, many natural forests in North Sumatra Province have been converted to crop plantations, tree plantations, and dryland agriculture. A similar situation is also occurring in Aceh and West Sumatra. Land conversion is also taking place in watershed areas.

Sapta Ananda Proklamasi, senior researcher of the Greenpeace Indonesia Forest Campaign Team, says most Sumatra watersheds are in critical condition, with natural forests covering less than 25% of their original range.

“Now only 10 to 14 million hectares [54,000 square miles] of natural forest remain in Sumatra — less than 30% of the island’s 47 million hectares,” he says.

The decrease in forest cover must be taken seriously, as it changes the environment’s carrying capacity and resilience.

He adds that a thorough investigation is needed into the large number of small and large pieces of wood swept away by the floods in Sumatra.

“It could be from old or new logging, or incomplete land clearing,” Sapta says.

Arie Rompas, chair of the Greenpeace Indonesia Forest Campaign Team, echoed these concerns, saying the increasingly severe climate crisis, coupled with damaged forests and declining environmental carrying capacity, will further hurt the community. The government must also acknowledge that forest and land management have been conducted improperly.

“As a result, the forests of Sumatra are nearly depleted, severe environmental degradation has occurred, and now the people of Sumatra must bear the high cost of this ecological disaster,” says Arie.

Nearly two months after the disaster, millions of people across Sumatra remain displaced. Floods have damaged roads and bridges, cut off villages, and left widespread mud, debris, and power outages.

Zul, of Lintang Bawah City, Aceh Tamiang, says floods there rose up to 15 feet. The city was among the worst hit by the flash flood.

“My family is just surviving on whatever we have,” he says. “We only have the clothes we’re wearing and [did not eat] for three days during the flash floods; we’re just collecting rainwater to drink.”

Local leaders across Aceh are urgently calling on the government to declare a national emergency to enable the swift allocation of additional funds for rescue and relief efforts.

The post Photo Essay: Climate Change and Deforestation Collide in Indonesia’s Deadly Floods appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post The Seduction of Despair, the Persistence of Possibility appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>Not dramatically, not like a crashing wave or a siren, but quietly, like a fog: soft at first, then everywhere. It shows up on my phone, in headlines, on social media: policies rolled back. Protections stripped. Science defunded. Expertise ridiculed. Species disappearing. A political climate that feels more handheld flamethrower than democratic process. And beneath all of that, the quiet exhaustion of living through cascading crises without a pause button.

It’s especially loud now, at the turn of the year, a time when we’re told to make plans, set goals, and imagine better futures. But imagining can feel dangerous when the world feels fragile. The idea of resolve can seem almost laughable.

Despair is seductive because it offers a strangely rational refuge: If everything is collapsing, then nothing is required of you anymore. And there’s relief — brief, dangerous — in imagining the story is already over.

But despair isn’t neutral. It doesn’t just describe reality. It shapes it. Despair hands momentum to the forces counting on our fatigue. To the industries that benefit when we withdraw. To leaders who flourish when we believe we are powerless. It masquerades as honesty. Underneath it is permission — not to feel, but to quit.

Why We Stay in the Work

There have been days — fieldwork days, policy days, loss-of-another-species days — when I thought: Maybe the wild world will outlive us. Maybe the most we can do is bear witness to the ending. But then I think of future generations forced to inherit a planet stripped of its complexity and wildness, and bearing witness feels too much like quiet betrayal.

And then something interrupts. A headline — quiet, almost buried — about wolves returning or a coastal ecosystem recovering faster than expected. A student’s email saying they never realized nature was part of their story too, even from a city block surrounded by concrete. A grainy livestream of coral spawning — imperfect, but undeniable evidence that life is still trying. A community cleanup that began with six hesitant strangers and somehow became a recurring ritual people now protect on their calendars. A message from someone I’ll never meet saying they felt less alone because I didn’t give up.

And then, perhaps most powerful, I sit in a folding chair at a community meeting. The room isn’t glamorous. There’s no dramatic soundtrack. People are tired. Some are angry. Some are afraid. No one knows everything. But they showed up anyway. And in that small, imperfect room, I remember: Despair isolates. Community builds momentum.

We Are Not at the End — We Are at the Fork

This is a threshold moment. The kind future generations will study — not because we were certain, but because the uncertainty cornered us into choosing who we were willing to be.

History is full of inflection points when the future could have veered toward collapse or reinvention. And in those moments, there were always people who refused to leave the page blank: people who showed up tired. People who acted without guarantees. People who believed — not because the outcome was certain, but because living without trying felt unbearable.

That’s us now. Not the first generation to fight for wildlife, rivers, forests, or ocean. Not the last. But the generation with the least time to hesitate.

So what do we do when despair feels stronger than resolve? We don’t banish it. We don’t pretend we’re immune. We learn to feel it — and then move anyway.

Here’s how we keep going — not perfectly, but sustainably.

1. Shrink the Horizon.

Not everything needs to be solved at planetary scale. When the global feels unbearable, go local. This isn’t evasion, it’s strategic retreat. When we successfully restore one stream, one prairie, one forest patch, one shoreline, we break the logic of despair that says our efforts are futile. We create our own momentum. Small work is not small if it moves the world forward.

2. Build Belonging, Not Just Awareness.

Loneliness is one of despair’s most reliable accomplices. Hope doesn’t thrive alone. Find your people — the conservationists, scientists, artists, kids, elders, divers, farmers, fishers, hikers, hunters, dreamers, pragmatists — anyone who still believes a living planet is worth fighting for.

Community transforms despair from a boulder into a load shared. Show up to talks. Host a nature walk. Make space for questions, grief, curiosity, laughter, failure, and trying again. Movements don’t survive because they are correct. They survive because they are connected.

3. Let Awe Recalibrate You.

Get on your belly at the edge of a tidepool and watch barnacles open, each one waiting for the right moment to feed as the tide breathes in. Watch ants rebuild a colony after rain. Follow animal tracks in the snow. Stand beside a river and notice its pull. Watch a storm build over a lake and feel how water holds mood and memory. Plant native grasses and discover how soil — quiet, unglamorous soil — becomes an ecosystem. Grab a map and trace the flight paths of migrating birds overhead. Watch a livestream of a loud, chaotic romp of giant river otters in the Amazon and feel how wildness doesn’t apologize for taking up space.

Awe doesn’t erase the grief, but it reminds us why grief exists in the first place: because we love something worth protecting.

4. Act Anyway.

Even when discouraged. Even when unsure. Even when afraid. Action is not the opposite of despair — it is the antidote that makes despair bearable.

Write. Vote. Volunteer. Donate. Protest. Teach. Repair. Create. Speak up in rooms where silence is easy. Hope grows where footsteps repeat.

5. Rest. Seriously.

Burnout doesn’t make you a martyr. It makes you absent. Rest isn’t quitting; it’s recharging the part of you that refuses to give up.

Even ecosystems rest: Seasons shift, fires reset forests, tides withdraw, storms spend themselves. Your rest is part of the rhythm, not a deviation from it. Rest doesn’t pause the movement. It preserves the mover.

The Persistence of Possibility

Here’s a truth: Despair is honest.

Hope is honest, too. The difference is that hope participates. Hope has calluses. Hope stumbles and keeps going. Hope is the quiet refusal to surrender the future. The living world is not gone. And neither are we. This story isn’t finished. We are still writing it… species by species, action by action, community by community.

So as we step into 2026, maybe the resolution isn’t flashy or tidy. Maybe it’s this: Show up. For the wild. For each other. For the future. Some days that will mean attending hearings. Some days that will mean protecting your rest. Some days it will simply mean refusing to say “It’s too late” even when despair feels convincing.

Hope isn’t something we wait for. It’s a discipline we practice.

And as we cross into this new year — with uncertainty in one hand and possibility in the other — we make a quiet, stubborn promise: We will not hand the living world over to despair. Not this year. Not while we are here. Not while there’s still something left to protect.

The post The Seduction of Despair, the Persistence of Possibility appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>The post Species to Watch in 2026 appeared first on The Revelator.

]]>We’d do well to pay attention to these 20 species (or 21, depending how you count them). The threats and opportunities these animals and plants face could mean the difference between disappearance and survival, but they also illustrate the situations faced by countless other species around the world — including Homo sapiens.

Kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) — These endearing flightless parrots are about to enjoy what could be their best breeding season since 1977. And they need it: Only 242 of the critically endangered birds remain, on three remote, predator-free islands off the coast of Aotearoa New Zealand. They breed about every 2-4 years, when a native conifer called the rimu tree produces its nutritious fruit. This year 84 kākāpō females could potentially lay eggs, and while not every female is guaranteed to reproduce — nor every egg or chick guaranteed to hatch or survive — 2026 could still be a banner year.

And we won’t need to wait too long for the results: Nesting and hatching season will take place from January to March, and conservationists will monitor the chicks through May. They won’t manage the process as heavily as in past years — the goal is to establish a self-sustaining population that doesn’t need as much human intervention — but I expect plenty of photos of eggs, chicks, and proud kākāpō parents in the months ahead.

North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) — These critically endangered baleen whales are already in their calving season, which will run through mid-April. And as with the kākāpō, every newborn matters.

North Atlantic right whales have had a hard time the past few years, with more than 20% of the population dying after being entangled in fishing gear or struck by boats or ships. Their population fell about 25% from 2010 to 2020 but has been on the upswing since then, rising 7% since the start of this decade to an estimated 384 whales.

The good news: As of this week, conservation teams have already spotted an amazing 15 calves — a great start to the season. But at the same time, a male whale named Division experienced “life-threatening” fishing-line entanglements, with the cords embedded in his jaw and cutting his blowhole. A two-day rescue effort appears to have saved his life — but the crisis reminds us that many threats remain for these struggling whales.

Pangolins — These scaly anteaters from Africa and Asia are among the world’s most-trafficked species, and that’s put them on the fast track to extinction. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed legal protection for seven of the eight (or is that nine?) pangolin species, with a decision due in 2026. The United States hasn’t been directly linked to much pangolin trafficking, but federal protection here would lend support to international efforts.

Unfortunately the Trump administration wants to dismantle or neuter the Endangered Species Act, so the fate of the proposal seems uncertain at this time — a situation that echoes throughout the rest of this list.

Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) — This third orangutan species, only described by science in 2017, may have a hard time making it out of this decade. A massive flood this November wiped out somewhere between 6-11% of the species’ population, which before this disaster was estimated at just 800 apes. As Gloria Dickie wrote for The Guardian, Tapanuli orangutans only reproduce every six to nine years, so this mass mortality is a terrible blow. Much of their habitat and food also got washed away, so the survivors will have an especially hard time recovering.

It doesn’t help that gold miners have taken aim at Tapanuli orangutans’ habitat. Not only have roads further carved up the apes’ territory, but the deforestation and land degradation caused by a billion-dollar mining project may have made the recent flood much worse.

White storks (Ciconia ciconia) — These long-legged birds are widespread throughout much of Europe, Asia, and Africa — but not so much in Britain, where the last breeding birds were documented in 1416. The storks were wiped out in the British Isles by habitat loss, overhunting, and persecution. But in 2026 conservationists aim to return the birds to the skies around London for the first time in 600 years in one of the world’s most visible rewilding and reintroduction efforts.