| CARVIEW |

The talk takes you through some of the ideas and findings that will appear in StudyingFiction‘s forthcoming book!

Click the image or below to access the video.

NB/CORRECTION: At 26:00 I accidentally say ’88 *percent* of participants said’ where I should have said ’88 *participants* said’. The data is correctly displayed on the slide.

The talk explores some initial findings from the ‘Talking About Texts’ study, an anonymous questionnaire completed by 650 participants. Respondents shared their experiences of the relationships that can exist between reading and discussing books, and our sense of identity, covering topics such as honesty and dishonesty, embarrassment and judgement in relation to talking about texts.

In particular, it considers how pressures on English teachers and academics to present as prolific readers can shape perceptions of the subject, and what it means to be good at it. It will explore talk about texts as a socially and culturally loaded aspect of reading, which often requires individuals to disclose whether or not they are familiar with specific works and their attitudes towards them.

]]>Cognitive linguistics, and specifically cognitive poetics, is a relatively new discipline within the field of language and linguistics. The last fifteen years have brought huge advances in our understanding of reading and the mind, not just in terms of basic language acquisition and literacy development, but the fundamental tenets of what it means to read and engage with fiction. Current work in the field is beginning to understand why a text can make a reader grieve for a character they know was never real, physically increase their heart rate and prompt genuine fear responses, even make them look at the world differently and affect their real-world behaviours. We believe that this research is of huge potential value to English education practitioners and researchers alike, working across the full range of provision from Early Years to Higher Education.

Our book will offer an academic, accessible and applied overview of the latest work in cognitive linguistics in the context of studying fiction. Chapters will include exploration and discussion of

- Reading and the mind

- A history of literature teaching in schools

- Reading, attention and cognition

- Re-reading

- The roles of readers and writers in creating meaning

- Empathy and social justice

- Choosing fiction: children’s and YA literature in education

We’ll also be keeping updating this blog regularly as we work on the manuscript – watch this space for more details!

]]>

Every year there are a few essays that are too important and salient to discussions in the profession not to ask the students whether we could share them with the StudyingFiction readership and this year is no exception. Here’s the second of these, by Jennifer Henson (@jenhensonn): a powerful, insightful and academically-grounded reflection on the author’s experiences of setting and mixed ability grouping, and its potential impact on student well-being. The paper also offers a comprehensive overview of key research on setting which should be a useful resource for all teachers interested in finding out more about the academic work on this area. Enjoy! We’d love to hear your thoughts on Jennifer’s reflection and your own views on setting.

A First-hand Account of Setting, Attainment and Well-being, by Jennifer Henson

In the UK, children in public schools can be split into teaching groups in numerous different ways. Sukhnandan (1998) has produced definitions of streaming, setting, banding, within-class grouping and mixed ability teaching. When discussing the different forms of grouping within this account, I will be using these definitions. However, I have not personally experienced streaming or banding at this point in my education, therefore it is unlikely that these will be mentioned or discussed in great detail.

Setting: ‘The (re)grouping of pupils according to their ability in a particular subject. Setting can be imposed on a whole year group or on a particular band at a time’

Mixed Ability Teaching: ‘Teaching groups include pupils of widely ranging abilities. The spread of ability in such a group depends upon the ability range for which the school provides’

(Sukhnandan 1998: 2)

Sukhnandan also explains the purposes of each form of grouping, stating that: ‘setting can be used to reduce the size of teaching groups’ (1998: 4) and adds that Slavin (1978) believes that it ‘reduces the negative psychological effects on pupils that are often associated with streaming’. In contrast, ‘the aim of mixed-ability grouping is to provide individual pupils with individualised teaching that is specifically tailored for their needs’, consequently, ‘it provides all pupils with equality of opportunity… and reduces the negative consequences often associated with homogenous grouping [streaming and setting]’ (Sukhnandan 1998: 4).

After the 1944 Educational Butler Act was introduced, ‘streaming became the standard form of pupil organisation’ (Sukhnandan 1998: 7). However, ‘by the 1960’s the system of streaming had become increasingly unpopular’ (ibid). Following the introduction of major educational policies, including the National Curriculum, ‘there has been increased debate about the most effective way to group pupils in order to raise levels of attainment’ (Sukhnandan, 1998: 1), these debates have seen the introduction, and more common use of other forms of grouping, including setting and mixed-ability grouping. Ireson and Hallam suggest that ‘changes in the education system were accompanied by recommendations for schools to adopt setting by ability’ (2001: 8), quoting the government White Paper Excellence in Schools (1997) to say: ‘Unless a school can demonstrate that it is getting better than expected results through a different approach, we do make the presumption that setting should be the norm in secondary schools’. This forms the basis of a debate around what is the most beneficial form of grouping, but also whether student attainment is more important than student well-being.

During my time in secondary school, I experienced both setting and mixed ability teaching, during key stage four (KS4). Core subjects (English, Maths and Science) were the only subjects grouped in the form of setting, whereas optional GCSE subjects were mixed ability taught – due to the school not having control over who opted to study each subject. Interestingly, the school also chose to mix year tens and elevens within these optional lessons which created even less of an academic divide between students. Due to having experienced the two different types of grouping, I am able to present a first-hand account of how I perceived a direct effect that setting had on a student’s level of attainment and well-being, in comparison to mixed ability grouping.

Previous studies and research into setting and mixed ability teaching:

Ireson and Hallam (2001) provide an outline of the effects that ability grouping (selection and setting) has on students’ attainment and self-image. They state that although one of the main arguments for ability grouping is that it ‘enables teaching to be more effectively geared for pupils of differing abilities, allowing the most able to reach the highest standards’, it has an equally strong counter argument of ‘[denying] equality of educational opportunity to many young people, limiting life chances and increasing social exclusion’ (2001: 1). Exploring the first statement, it can be presumed that people are already aware that ability grouping only benefits “the most able”. Ireson and Hallam claim that although there is little research to suggest this is an accurate statement, it does still appear that there are ‘differential benefits for pupils in selective and unselective systems… selection and ability grouping tend to work to the advantage of pupils in higher attaining groups’ (2001: 17). Within their findings, it is also discussed that teachers also believe that ‘setting benefits the more able child [and that] there are more discipline problems in the lower ability classes’ (2001: 126) suggesting that time is taken away from students’ learning, to deal with these problems.

Ireson and Hallam have also highlighted the student well-being problems that setting can create. Mainly that, ‘placement in the bottom groups has an adverse impact on pupils’ self-esteem, self-concept and their attitudes towards school’ (2001: 40), they also uncover long term effects including ‘a reluctance to take up training opportunities… [and lack of] motivation to continue or return to education’ (2001: 206). They confirm that ‘pupils in schools with more structured grouping feel less positive about school’ (2001: 62).

Boaler, William and Brown (2000) also provide an insight into the effects that ability grouping has on students. Within the research, ‘high sets’ are linked to ‘high expectations [and] high pressure’ (2000: 635), whilst ‘low sets’ are linked to ‘low expectations [and] limited opportunities’ (2000: 637). However, it is suggested that, ‘the traditional British concern with ensuring that some of the ablest students reach the highest possible standards appears to have resulted in a situation in which the majority of students achieve well below their potential’ (2000: 646).

Barker (2003) provides a case study that compares both teaching mixed ability and a low ability English class. Barker found that ‘the teaching of mixed ability groups makes greater demands on teachers’ (2003: 13), however, she preferred to teach this way, rather than by sets. This is likely to be due to the many negative impacts being placed in a low ability set has on a student, for example ‘[being in a low ability class] damages their chances for improvement… damages working conditions and self-esteem’ and also means that ‘potential is repeatedly limited’ (ibid).

Mills (1977) more explicitly discusses the effects of mixed ability teaching, that he discovered when exploring teaching strategies for use in mixed ability English lessons. These effects include: ‘concentration on needs of individual, wide provision of multi-media materials [and] flexible grouping of learning’ (1977: 28). Mills presented this in his model, entitled The Singing Spheres, which identifies ‘wider implications which may be faced by the whole school when one of its departments moves to mixed ability work’ (1977: 27), The corresponding implications of the aforementioned effects were ‘revision of remedial policy, resource centre [and] intra and inter departmental cooperation’ (1977: 28). Within this model, Mills highlights that mixed ability teaching can be beneficial for both teachers and students. When taking this account of benefits from a teaching point of view, and putting it with the suggested benefits from anti-setting studies, considering also that Ireson and Hallam confirmed that previous research on grouping by ability has ‘rather little impact on overall entertainment’ (2001: 38), it appears that mixed ability grouping is the most beneficial form of grouping for students.

To summarise, the current literature surrounding what style of grouping is best used suggests that there is no proven correlation between setting and attainment, but, there is a proven correlation between setting and student well-being.

A Personal Reflection

In all three of my core subjects, which were grouped via setting, I was predicted A grades. I only achieved this in English Language and Literature, whilst achieving D’s across the board in science and a C in foundation Mathematics in Year Nine – I attained the same grade on the higher paper in Year Eleven. This shows clearly that, in my case, setting resulted in low attainment of grades. The most notable aspect of my case is that I was more successful in English, where I was placed in a set two class, than I was in both subjects in which I was placed in the highest set. This supports what Boaler, William and Brown found in their case study, as many students claimed that ‘they could not cope with the fast pace of lessons and the pressure to work at a high level’ (2000: 635). This is something that I personally related to at school, as even though I had been placed in the top sets, I still doubted my ability to perform at the same academic standard as my peers.

My mixed ability, optional subjects appear to be my highest performing area when looking at my GCSE results. I managed to attain distinctions in Art and ICT, a B in Religion and Geography and a C in Media Studies. I achieved all of my target grades in these subjects, even exceeding them in Art and Geography. During these lessons, I felt more comfortable about the pace of the learning, and also benefited from the different teaching strategies that were being used. Again, this supports what Boaler, William and Brown found in their case study, where one student fed back that when they were not in a mixed ability group the previous year, ‘it [was] a whole different process… you’re not being rushed all the time’ (2000: 636). Throughout their study, statistical data is used to compare how students feel about the different areas being researched, and each time mixed ability group students expressed a more positive experience in the classroom (2000: 637-43).

Although this suggests that mixed ability teaching was more beneficial in my case, other variables can be seen to affect my attainment. For example, within my optional subjects I had lower target grades. It could also be argued that the core subjects are perhaps considered “more important”, as they are the only subjects compulsory for further education, therefore putting more pressure on both teachers and students in secondary education.

One of my strongest memories of secondary school, was the disappointment I felt in Year Ten, when my English teacher told me I had been dropped to set two. Although I was still in the top performing half of the year group, I felt that I had severely let myself down as I had always been labelled a “top set student” by teachers, and had conceptualised my school, and self-identity around this. In retrospect, the move to a lower set was a positive move, as the learning style and pace was more suited to my educational needs and thus meant I attained a higher grade. However, as a 14-year-old that had spent her time in education as a “top set student” this wasn’t something I considered, or even cared about. During your teenage years, you tend to be more concerned over your image and how other people perceive you – I had always been “the clever one” in my friendship group, and all of a sudden, I was in the same classes as my friends. The only unique aspect of my identity had been taken away from me.

Taking both aspects of my personal experience into account, there is a reflection of what is portrayed throughout the literature: there is no proven correlation between setting and attainment, but, there is a proven correlation between setting and student well-being.

Again, it should be taken into account that when analysing both attainment and wellbeing in schools, there are many other variables that should be taken into account: These are outlined by Ireson and Hallam (2001:36, 99), Barker (2003:7) and Boaler, William and Brown (2000:635). All three of these studies mention gender, and their other considerations include: differences across the curriculum, individual schools’ ethos and teacher’s and student’s individual values.

It should also be noted that many prior researchers concentrate on the idea of equality in education. When they should perhaps be concentrating on equity in education, this has been explored by Duncan-Andrade (2007), who usefully makes a distinction between the two:

‘An equal education implies that everyone gets the same amount of the same thing and is often measured by things that can be counted (i.e. per pupil expenditures, class size, textbooks, percentage of credentialed teachers). Thus, an equal education attempts to provide the same education to everyone, which is not equitable. An equitable education suggests resource allocation based on context, which would include attention to funding and teachers but in a manner that pays closer attention to the specific needs of a community.’

(Duncan-Andrade 2007: 618).

Equitable education ‘is designed to address the material conditions of students’ lives while maintaining a high level of intellectual rigor’ (p618). However, despite this distinction being made, there is still no educational policy to ensure this is sustained through any particular means of grouping and teaching in schools and the relationship between equity and setting is not clear cut.

By comparing setting and mixed ability teaching through prior research and personal experience, I feel that I have a sufficient amount of data, knowledge and experience, as to put forward a case in favour of mixed ability teaching. However, I think it should be noted that as all students are different, and it is impossible to generalise from data in studies as each case produces a different argument. However, it may be easier to decide which type of grouping is more beneficial, by comparing attainment directly to wellbeing of students, and then finding the source of problems uncovered from this.

References

- Barker, A. (2003). Bottom: A case study comparing teaching low ability and mixed ability year 9 english classes. English in Education, 37(1), 4-14. doi:10.1111/j.1754-8845.2003.tb00586.x

- Boaler, J., Wiliam, D., & Brown, M. (2000). Students’ experiences of ability grouping – disaffection, polarisation and the construction of failure. British Educational Research Journal, 26(5), 631-648. doi:10.1080/713651583

- Duncan-Andrade, J. (2007). Gangstas, wankstas, and ridas: Defining, developing, and supporting effective teachers in urban schools. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(6), 617-638. doi:10.1080/09518390701630767

- Ireson, J., & Hallam, S. (2001). Ability grouping in education (1. publ. ed.). London: Chapman.

- Mills, R. W. (1977). Teaching english across the ability range. London: Ward Lock Educational.

- Sukhnandan, L. (1998). Streaming, setting and grouping by ability. Slough: NFER

The module is a research-driven exploration of current issues and debates in English education and, for their first assignments, students write research essays about a topic of their choosing related to English education. They are able to include critical personal reflections of their own experiences of studying English, both at school and university.

Every year there are a few essays that are too important and salient to discussions in the profession not to ask the students whether we could share them with the StudyingFiction readership and this year is no exception. As such, I’m thrilled to introduce the first such essay, by Rebecca Evans (find her on Twitter at @beckicklesie) . This is a nuanced and insightful reflection on her son’s formative experiences with reading, writing, and literacy, and the potential power of reading for pleasure. We hope you enjoy it as much as we did, and would love to hear your thoughts.

The power of reading for pleasure: organically enhancing literacy, academic achievement, and personal development in the classroom

‘When we read, we really have no choice – we must develop literacy’

(Krashen 2004:150).

In recent years, studies investigating the importance of ‘reading for pleasure’ have presented significant evidence (Department for Education 2012: 3) in support of its positive influence on children’s academic attainment, personal development, and social skills (Allan et al. 2005). Research (Clark and Rumbold 2006; Clark 2011) reliably reveals that children generally enjoy reading, with only one in ten children, aged 8 to 17, claiming to ‘not enjoy reading at all’ (Clark 2011: 14). Yet, there is a growing, substantial body of research that indicates young people are becoming increasingly unlikely to read for pleasure (Clark and Rumbold 2006; Twist et al. 2007; OECD 2010).

Inspired by a personal account, which demonstrates academic and personal benefits of positive reading relationships, this paper aims to position ‘reading for pleasure’ as fundamental to educational achievement and personal growth, through the discussion of scholastic obstacles and strategies for motivation. It understands reading for pleasure as a ‘creative activity’ (Holden 2004); ‘reading that we do of our own free will, anticipating the satisfaction that we will get from the act of reading’ (Clark and Rumbold 2006:5).

Just a boy and his books

A little under three years ago, my son was approaching Key Stage One (KS1) Standard Attainment Tests (SATs). Having relocated from Lancashire to South Yorkshire the August prior, changing schools in the process, some experts would suggest he experienced educational disruption, potentially affecting academic performance (Audette et al. 1993; Astone and McLanahan 1994) and social behaviour (Fields 1997; Mantzicopoulos and Knutson 2000), amongst other factors (Rumberger 2003:8-11). Yet, throughout the entirety of his schooling, literacy had always presented as a difficulty. No matter the educational setting, he consistently worked slightly below ‘Age Related Expectations’ (ARE). For all the variation of accessible books at home, hearing stories each day, and engaging daily with the appropriate banded schoolbooks, in Year 1, his phonics screening check indicated that he wasn’t progressing sufficiently. He continued to struggle with weekly class spellings, no matter how much he practised at home, after school.

I invested in various phonics programmes. I continued to read with him and to him. We spent almost all weekends working through the ‘sight words’ 100 High Frequency Word Spelling List in its entirety, using the advised five-stage ‘look-say-cover-write-check’ method, ‘reconceptualised’ from the traditional working memory ‘look-cover-write-check’ process (Hammond 2004:15). Despite our efforts to improve his literacy, and although academics (Nies and Belfiore 2006; Cates et al. 2007) conclude this specific spelling strategy is ‘effective for improving recall of spelling patterns… [and] autonomy in spelling’ (Westwood 2008:29), my son made little progress across reading, writing, or spelling. As he began his Year 3 learning in 2015, he was diagnosed with mild dyslexia.

Regardless of results from national or ongoing educational assessments, my son’s relationship with reading prospered. Books had always been a comfort, reading a bonding activity we shared together. Stories are more than words on pages; we enjoy discussing characters and plotlines, watching film and stage adaptations, and engaging in book-themed activities, games, and crafts at home, locally, and across the country. My son uses the library, is a member of their book club, and reads out of choice each summer to complete the national Summer Reading Challenge (The Reading Agency 2017). He is a Sheffield Book Fairy (The Book Fairies 2017) and hides his favourite books across the city, for other children to find and enjoy. Furthermore, he watches me read to relax and enjoy the experience of engaging with various texts.

His ability to read for pleasure remained, regardless of academic attainment, because school achievement wasn’t the primary motivation. He has grown to know reading as an enjoyable, immersive pastime. Although he initially made slow progress into independent reading, every step was an incredible confidence boost. It was a stride towards him proudly identifying as an independent reader. He was encouraged by his capability to enjoy a wider selection of books, in his own company. His reading flourished further. Due to his desire to pick up a book, his love of reading, he pushed further and progressed at a greater rate. He is now an avid reader, who has his head ‘stuck in a book’ at every opportunity. As noted by Clark and Rumbold (2006: 9), it is no coincidence that due to this interest and drive, his literacy skills have improved significantly. At the end of Year 4, my son was working well above ARE in writing and reading for the first time in his schooling. He had achieved free-reader status, and had also begun writing, illustrating, printing, and selling his own comic book stories to friends and family. Additionally, he capably draws upon complex themes within narratives to sensitively explore emotive, challenging subjects, alone, and in discussion with me and other family members.

My son’s accomplishments in the face of academic difficulties, are a prime example of the ‘Matthew effect in reading’ (Stanovich 1986), which refers to a private ‘circular relationship between practice and achievement’ (Clark and Rumbold 2006:16). That is,

‘better readers tend to read more because they are motivated to read, which leads to improved vocabulary and better [literacy] skills’

(Clark and Rumbold 2006: 16).

This stimulates debate concerning the literacy teaching methods that are typically adopted throughout primary education. Specifically, it invites the question of whether increased capacity should be created, across classroom resources and timetabling, to enable children to experience pleasurable reading, with an aim of promoting the reciprocal facilitation between reading and literacy skills, as well as heightened cultural awareness (Meek 1991), personal development and wellbeing (Holden 2004; Clark and Rumbold 2006:7). Or, rather, does responsibility to foster this reader relationship lie with parents?

Creative reading in the curriculum and the classroom

Across all key stages of learning, the Department for Education (DfE) has overtly integrated ‘reading for pleasure’ within the overarching pedagogical aims of the current National curriculum in England: English programmes of study (2014). This statutory governmental guidance for educators asserts that through ‘widespread reading for enjoyment’ schools can ‘promote high standards of language and literacy’. What’s more, the curriculum advises that schools can equip children with skills integral to their cultural, emotional, intellectual, social, and spiritual development, simply through encouraging a ‘love of literature’ (DfE 2014).

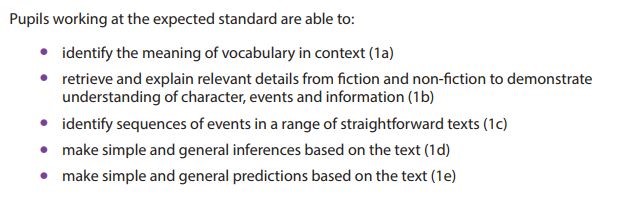

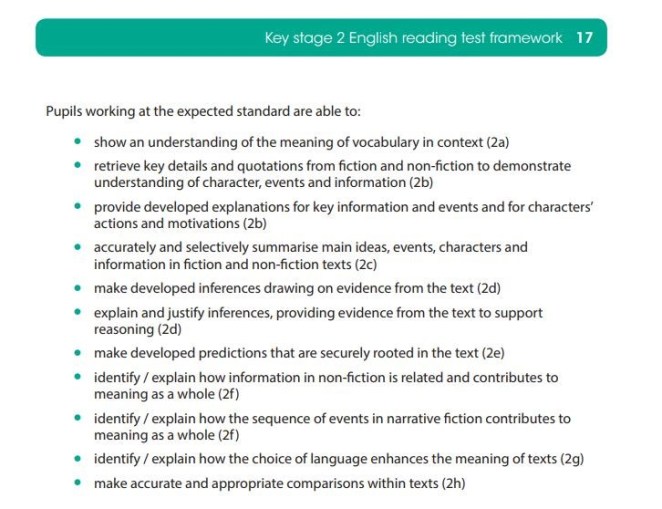

While reading for enjoyment does feature within the premise of the National Curriculum, this does not directly represent how a child’s attainment is tested. No aspect of the National Literacy Strategy (NLS), including SATs, investigates the child’s interest in reading. Nor does it reward them for developing a rich reader relationship with the text. In contrast, children’s authors, (for example Powling et al. 2003) argue that the NLT has instead discouraged the concept of reading for pleasure entirely. Rather, focus is placed on a child’s understanding of, and ability to, demonstrate standard cognitive reading practices. This scopes a number of comprehension centred tasks, as detailed, for example, in the KS1 and KS2 marking schemes performance descriptors (see below)

While reading for pleasure has been found to improve ability in this area (Cipielewski and Stanovich 1992; Elley 1994; Cox and Guthrie 2001), it is not a prerequisite of a child meeting the detailed age expected attainment levels. Consequently, due to the pressures placed on teachers to ensure children achieve such targets, the importance of reading for pleasure can quickly become lost in the classroom, as reading and analysing a text specifically to satisfy marking frameworks become a priority. As noted by Harris (2017), the

‘assessment regime has created a culture that has allowed for[…] schools with a very narrow curriculum[, in which] teaching and learning [is] specifically aimed at “passing” the test’.

As such, ‘manufactured readings’ (Giovanelli and Mason 2015) are consistently imposed upon young people throughout education. As they are ‘denied the space to engage in their own process of interpretation’ (Giovanelli and Mason 2015: 46), the opportunity to experience their own authentic reading, to build an enjoyable, rich, individual reader relationship with the text, is diminished.

This viewpoint reflects findings presented by Goodwyn (2012), whose research investigated English teacher reactions to the KS3 and KS4 Framework for English on literature teaching. From the 90 per cent of Goodwyn’s participants who chose to respond by providing comments, there was an overwhelming opinion that ‘literature teaching had become much more instrumental, dominated by narrow objectives and focused on textual extracts’ (2012: 220). Teachers involved in the study also expressed their ‘frustration’ that English teaching had become ‘scripted’ with ‘the emphasis being constantly on the assessment objectives’ rather than allowing students a ‘personal’ or ‘creative’ relationship with texts (Goodwyn 2012:220-221).

As noted by Sheldrick-Ross et al. (2005:244), ‘the gift of reading can best be given by another reader who models what it is like to get pleasure from reading’. While around 75 per cent of training English teachers report they ‘have always loved reading’ (Goodwyn 2002: 66), the degree of disillusion induced by stringent national strategies minimises the opportunity for much ‘enjoyment of reading’ to be demonstrated in the classroom. Pupils, therefore, are missing out on the chance to benefit from some of the primary positive influencers in their development as readers.

‘Booking up’ ideas on attainment

My son’s accomplishments merely represent a solitary example of the benefits to be gained from the enjoyment of reading. While ‘free voluntary reading alone will not ensure attainment of the highest levels of literacy, it will at least ensure an acceptable level’ (Krashen, 2004:149-150), forming a receptive, contextualised foundation for related learning:

‘When children read for pleasure[…] they acquire, involuntarily and without conscious effort, nearly all of the so-called ‘language skills’ many people are so concerned about: they will become adequate readers, acquire a large vocabulary, develop the ability to understand and use complex grammatical constructions, develop a good writing style, and become good (but not necessarily perfect) spellers’

(Krashen, 2004: 149).

This assertion is further supported by Clark and Rumbold’s (2006) research, which cites several academics to establish that reading for pleasure benefits text comprehension, grammar, and reading ability, amongst numerous other personal benefits, including increased general knowledge and improved social and emotional wellbeing (2006: 9-10). Moreover, children provided with the necessary space and resources to become active readers perform better across the board in other school subjects, including mathematics, regardless of their socioeconomic background (Sullivan and Brown 2013). It becomes apparent that, whatever your stance concerning the role of English in the curriculum, reading for pleasure can successfully fulfil subject objectives across its incarnations.

While evidence (Baker and Scher 2002; Flouri and Buchanan 2004; Clark and Rumbold 2006) does strongly suggest that children are more likely to develop an authentic love of reading if they are from a home environment where reading is valued, educational professionals can but try to influence home-based reading activity. With this in mind, it seems only essential that learning strategies and educational resources be re-designed to give children of all genders, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds, the chance to engage with texts for enjoyment in a school environment. Given whether a child reads for pleasure is the superlative indicator of their educational success (OECD 2002), schools have a responsibility to build opportunity for this experience into their literacy and PSHE frameworks. The foundation for lifelong reading may be established at home, in the early years, but ‘we also know that it’s never too late to start reading for pleasure’ (Sheldrick-Ross et al. 2005: 244).

Self-selecting for success

Reading for pleasure is an accessible activity, which enables children to succeed academically, and thrive developmentally, socially, and emotionally. Simply through systematising schooling, so key motivators are incorporated, educational and personal experience can be enhanced. While it would be inappropriate to suggest contributions to English curriculum reforms here, ample academics have explored why children choose to read. A consistent principle finding places ‘freedom of choice’ as a vital variable (Krashen 2004; Gambrell 1996; Schraw et al. 1998; Moss and Hendershot 2002; Clark and Phythian-Sence 2008), with pupils who self-select texts reading more and generally demonstrating a higher level of ‘grammar, vocabulary, reading, comprehension, and spelling’ (Krashen 2004: 2). While school reading programmes, or banded books, are designed to incorporate phonics and other KS1-2 literacy objectives, the enjoyment of free reading overrides any prescriptive reading structures, with research ‘finding… “no [academic] difference” between free readers and students in traditional programs’ (Krashen 2004:2).

Perhaps, most importantly, just as my son struggled in literacy, pupils can present as reluctant readers for myriad reasons. ‘We must therefore address the possible issues that make an individual a reluctant reader and use creative solutions to combat this disengagement’ (Clark and Rumbold 2006: 27), guiding children to self-select the right book at the right time, to facilitate an independent relationship with reading. Although the conventional ‘class reader’ approach may function to address ‘cultural heritage’ awareness, it rarely serves the individual child, their aptitude for language and literacy, or their personal development, as a rounded pedagogical approach. Other influential strategies, including ownership of books (Clark and Poulton 2011), reading-related rewards (Clark and Rumbold 2006), and child-teacher interaction (Cremin et al. 2009) are known to be highly effective motivators. Nonetheless, it seems that simply allowing children to read what they want, when they want, is the most integral, initial step we can take to organically enhance children’s’ literacy, academic achievement, and personal development.

References

- ALLAN, J., ELLIS, S. and PEARSON, C. (2005). Literature circles, gender and reading for enjoyment. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

- ASTONE, N. and McLANAHAN, S. (1994). Family structure, residential mobility, and school dropout: a research note. Demography, 31(4), 575–584.

- AUDETTE, R., ALGOZZINE R., WARDEN, M. (1993). Mobility and School Achievement. Psychological Reports, 72, 701-702.

- BAKER, L. and SCHER, D. (2002). Beginning readers’ motivation for reading in relation to parental beliefs and home reading experiences. Reading Psychology, 23, 239-269.

- CATES, Gary L., DUNNE, Megan, ERKFRITZ, Karyn N., KIVISTO, Aaron, LEE, Nicole, and WIERZBICKI, Jennifer (2007). Differential Effects of Two Spelling Procedures on Acquisition, Maintenance and Adaption to Reading. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16(1), 70-81.

- CIPIELEWSKI, J. and STANOVICH, K. E. (1992). Predicting growth in reading ability from children’s exposure to print. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 54, 74-89.

- CLARK, Christina (2011). Setting the Baseline: The National Literacy Trust’s first annual survey into young people’s reading – 2010. London: The National Literacy Trust.

- CLARK, C. and PHYTHIAN-SENCE, C. (2008). Interesting Choice: The (relative) importance of choice and interest in reader engagement. London: The National Literacy Trust

- CLARK, C and POULTON, L. (2011). Book ownership and its relation to reading enjoyment, attitudes, behaviour and attainment. London: National Literacy Trust.

- CLARK, Christina, and RUMBOLD, Kate. (2006). Reading for Pleasure: a research overview. London: The National Literacy Trust. [online]. Last accessed 9 November 2017 at: https://literacytrust.org.uk/research-services/research-reports/reading-pleasure-research-overview/

- COX, K.E. and GUTHRIE, J.T. (2001). Motivational and cognitive contributions to students’ amount of reading. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26(1), 116-131.

- CREMIN, T., MOTTRAM, M., COLLINS, F., POWELL, S. and SAFFORD, K. (2009). Teachers as Readers: Building Communities of Readers 2007-08 Executive Summary. London: The United Kingdom Literacy Association.

- DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION (2012). Research evidence on reading for pleasure. [online]. Last accessed 9 November 2017 at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/284286/reading_for_pleasure.pdf

- DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION (2014). National curriculum in England: English programmes of study. [online]. Last accessed 8 November 2017 at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study

- DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION (2015a). Key stage 1 English reading test framework National curriculum tests from 2016. [online]. Last accessed 8 November 2017 at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628806/2016_KS1_Englishreading_framework_PDFA_V2.pdf

- DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION (2015b). Key stage 2 English reading test framework National curriculum tests from 2016. [online]. Last accessed 8 November 2017 at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/628816/2016_KS2_Englishreading_framework_PDFA_V3.pdf

- ELLEY, W. (1994). The IEA Study of Reading Literacy: Achievement and Instruction in Thirty-Two School Systems. Oxford: Pergamon.

- FIELDS, B. (1997). Children on the move—the social and educational effects of family mobility. Children Australia, 22(3): 4–9.

- FLOURI, E. and BUCHANAN, A. (2004). Early father’s and mother’s involvement and child’s later educational outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74: 141-153.

- GAMBRELL, L.B. (1996). Creating classroom cultures that foster reading motivation. The Reading Teacher, 50: 14-25.

- GIOVANELLI, M. and MASON, J. (2015). ‘Well I don’t feel that’: Schemas, worlds and authentic reading in the classroom. English in Education, 49(1): 41-55.

- GOODWYN, Andrew (2002). Breaking up is hard to do: English teachers and that LOVE of reading. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 1(1): 66-78.

- GOODWYN, Andrew (2012). The Status of Literature: English teaching and the condition of literature teaching in schools. English in Education, 46(3): 212-227.

- HARRIS, Colin (2017). A new culture of primary testing that doesn’t stress out teachers and make pupils feel like failures? Fat chance. TES. [online]. Last accessed on 9 November 2017 at: https://www.tes.com/news/school-news/breaking-views/a-new-culture-primary-testing-doesnt-stress-out-teachers-and-make

- HAMMOND, Lorraine (2004). Getting the right balance: Effective classroom spelling instruction. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 9(3): 11-18.

- HIGH FREQUENCY WORDS (2017). First 100 High Frequency Words. [online]. Last accessed 10 November 2017 at https://www.highfrequencywords.org/hfw100fp.pdf

- HOLDEN, John. (2004). Creative Reading: Young People, Reading and Public Libraries. London: Demos.

- KRASHEN, S. (2004). The Power of Reading: insights from the research. 2nd ed. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

- MANTZICOPOULOS, P. and KNUTSON, D. (2000). Head Start Children: School mobility and achievement in the early grades. The Journal of Educational Research, 93(5): 305.

- MEEK, M. (1991). On Being Literate. London: Bodley Head

- MOSS, B., and HENERSHOT, J. (2002). Exploring sixth graders’ selection of nonfiction trade books. The Reading Teacher, 56: 6-17.

- NIES, Keith A. and BELFIORE, Philip J. (2006). Enhancing Spelling Performance in Students with Learning Disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 15(3): 163-170.

- OECD (2002). Reading for change: Performance and engagement across countries. Results from PISA 2000. [online]. Last accessed 9 November 2017 at: https://www.oecd.org/edu/school/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/33690904.pdf

- OECD (2010). PISA 2009 Results: Executive Summary. [online]. Last accessed 9 November 2017 at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/46619703.pdf

- POWLING, C., GAVIN, J., PULLMAN, P., FINE, A. and ASHLEY, B. (2003). Meetings with the Minister: Five children’s authors on the National Literacy Strategy. Reading: The National Centre for Language and Literacy.

- RUMBERGER, Russell W. (2003). The Causes and Consequences of Student Mobility. The Journal of Negro Education, 71(1): 6-21.

- SCHRAW, G., FLOWERDAY, T. and REISETTER, M.F. (1998). The role of choice in reader engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90: 705-714.

- SHELDRICK-ROSS, C., McCECHNIE, L. and ROTHBAUER, P.M. (2005). Reading Matters: What the research reveals about reading, libraries and community. Oxford: Libraries Unlimited.

- STANOVICH, K.E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4): 360-407

- SULLIVAN, Alice and BROWN, Matt (2013). Social inequalities in cognitive scores at age 16: The role of reading. London: Institute of Education, University of London.

- THE BOOK FAIRIES (2017). About Us. [online]. Last accessed 6 November 2017 at: https://ibelieveinbookfairies.com/

- THE READING AGENCY (2017). For parents and carers: What is the Summer Reading Challenge? [online]. Last accessed 6 November 2017 at: https://summerreadingchallenge.org.uk/parents-carers

- TWIST, L., SAINSBURY, M., WOODTHORPE, A. and WHETTON, C. (2003). Reading all over the world. National Report for England. Slough: NFER.

- WESTWOOD, Peter (2008). What Teachers Need to Know about Spelling. Camberwell: Acer Press.

It’s easy for us to forget that in real life, our sense of what another person is thinking is based on our best guess: whenever we interact with others we are running a dynamic mind-model based on all sorts of verbal and non-verbal cues, and often moderating our own behaviour according to what we think is going on in the other person’s head.

A mind-model which does not actually represent a good match to another person’s actual mind is at the root of many arguments and misunderstandings. Imagine a friend passes you in the street, looks at you, and completely ignores you. Your mind-modelling might go into overdrive, constructing that they have feelings of anger or annoyance towards you. You might begin wracking your brain to think what you could have done to provoke this reaction. You might even come up with something and either decide that it’s unreasonable, and then act angrily towards them or ignore them yourself the next time you meet, or feel remorse and perhaps call or text them to apologise. All the time, your friend was deep in thought about the latest episode of The Handmaid’s Tale and had forgotten to put their contact lenses in that morning. Here, well-reasoned but completely inaccurate mind-modelling has led to unsuccessful communication, and it’s easy to see, if you did reciprocate angrily towards your friend on your next meeting, how a series of miscommunications can escalate and even put the friendship in jeopardy.

Marking and feedback possesses all the hazards of inaccurate mind-modelling between teachers and students that we constantly traverse in day-to-day interaction. But with marking and feedback the situation is actually often much more precarious, for several reasons:

Classrooms and schools are inherently sites of unequal encounter (Fairclough 2014)

The power imbalance between teacher and students is always likely to subtly affect the nature of interaction, especially in terms of what students are willing or not willing to say. There’s no magic bullet to fix this issue, but we think that simply being mindful of it can be really useful. In terms of marking and feedback, This means that students are predisposed not to ask whether their mind-model for their teacher is accurate or not. This is like if, in the scenario above, you never ask your friend if or why they were ignoring you. In day-to-day interaction this is a key way in which disputes can escalate and relationships can break down, so it seem uncontroversial to suggest that there’s a risk of this happening in the classroom too.

Marking as Attenuated Interaction

Marking a student’s work involves several stages of mind-modelling. This is a highly attenuated process: each stage offers another opportunity for misinterpretation. In essence, the stages, through the lens of mind-modelling often look like this:

- Teacher tries to mind-model what the student will think when reading comments, viewing underlines, ticks, crosses and so on.

- Student, with little other than the teacher’s marking to go on, tries to mind-model what the teacher was thinking as they marked the piece of work and interprets the feedback accordingly.

If there’s a mismatch between mind-models there’s very little opportunity for this to be picked up.

What about dialogic approaches?

The idea of dialogic feedback, where students respond to teachers’ comments and perhaps then teachers even respond to those and so on, is relatively sound in principle. However, as when you’re writing your colleague a long email and you decide to just give up and call them instead, it’s difficult to see how a written dialogic approach can be as good as an actual conversation. Added to this a conversation is likely to take less time and offers more opportunities to make sure your understanding of what a student is struggling with is accurate.

Recently Pinkett wrote a great account of strategies he has employed in his own classroom, suggesting replacing written feedback with one-to-one sessions with students talking through their work with them:

‘twice weekly, midway through a lesson, once I’ve set the students off on an extended writing task (18 minutes minimum), I haul a desk to the front of the classroom and sit myself down on a chair under the whiteboard, facing the class. […] One by one, students ‘come up’ and talk me through some of the work in their exercise books. They turn the pages and read sections of their efforts to me.’

(TES, Pinkett 2016)

From a mind-modelling perspective, Pinkett’s approach makes a huge amount of sense. Whilst marking provides a written record that feedback has been given, it seems a much less reliable way of conveying accurate feedback to students than having a conversation with them if that conversation offers good opportunities for accurate mind-modelling on both sides. If your school insists on a written record, could you adopt Pinkett’s approach and then ask students to write up the key points of your discussion when they return to their desk?

Verbal feedback also offers teacher and students opportunities for queries and clarification not typically offered by written feedback. Here additional opportunities for catching misinterpretations by recalibrating mind-models for one another are introduced into the teacher-student interaction.

Time!

A key issue with providing written marking and feedback is, as every teacher is well aware, the huge amount of time it can take. A particular issue with this in terms of mind-modelling, however, is what we can tend to cut out of the feedback in order to make the job a little quicker. Three things that are naturally susceptible to the chop are:

- Hedging: ‘There are some slight issues with your style’ can become ‘Issues with style’

- Complete syntax/fuller explanations: ‘This paragraph isn’t adding anything to your argument, you could cut it out’ can become ‘Cut’ or even just a line through the paragraph.

- Positive comments: Whilst most teachers agree that it’s nice to have positive comments to balance out critiques, faced with 50 essays on a weekend day and reflecting on what is really going to help students improve, positive comments can quickly seem like a time cost that there simply isn’t room for.

One issue with this natural attrition of these stylistic features of a teacher’s feedback is that if a student is using the marking that remains to construct a mind-model of what the teacher thought of their essay the loss of these features can result in inaccurate modelling that teacher is rude, teacher doesn’t like me, teacher thinks this essay is rubbish, teacher thinks I am rubbish. When this is compounded with the power imbalance meaning that students are less likely to actually ask their teacher if these modelling are accurate, this can mean that students become resistant to taking any feedback on board at all. We are certainly not suggesting that teachers should therefore double their marking time by keeping these features in but we think that being aware of these dangers is really valuable.

Some strategies that might be helpful

- Could you help students to understand why these features are absent through meta-narration: ‘you might look at some of the comments on your work and think that they seem a bit rude, so I just want to take a moment to discuss this…’. This is a good potential strategy for two reasons. First, it takes much less time to reinsert all of the hedging, positivity and full explanations verbally that get lost when they’re written down. Second, it offers students more information with which to construct their mind-model for you, which can head off the inaccurate modelling before it occurs.

- There seems to have been a recent shift towards whole class feedback – from a mind-modelling point of view this makes a lot of sense because it decreases the level of threat posed by criticisms to individual students.

- Verbal interactions about work create more opportunities for both teacher and student(s) to establish an accurate mind-model for one another and, crucially, for inaccurate modelling to be identified and redressed.

- Could you experiment with getting some students to do what researchers call a think-aloud protocol with some of your marking and feedback. This would mean getting students to silently read through their essay with your comments and asking them to say what they’re thinking as they read about what they think you’re asking for and what you think of the piece of work. This might be an interesting way to try to see how your students are mind-modelling you and could even be used as a foundation to engage your classes in discussion about marking and feedback, it’s advantages, pitfalls and how everyone could make it work more effectively.

We hope you’ve found this cognitive perspective on marking helpful, let us know your thoughts in the comments or on Twitter at @studyingfiction

References

Fairclough, N. (2014) Language and Power. Second Edition. London: Routledge.

Pinkett, M. (2016) ‘The teacher who gave up marking and thinks that you can too’, Times Educational Supplement. Available online here: https://www.tes.com/news/school-news/breaking-views/teacher-gave-up-marking-believes-you-can-too

Stockwell, P. (2009) Texture: The Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

]]>

When we mind-model other people we essentially draw on two main sources of information:

- Our prior knowledge of that person, which we mentally bring with us to the current interaction; and

- Cues we draw from the immediate interaction itself (discourse, tone, body language, verbal and non-verbal feedback, and so on).

If we don’t know the other person well, or even at all, then our prior knowledge is likely to be more heavily reliant on our generic knowledge schemas relating to characteristics we perceive that person to possess (age, gender, race, profession and so on), as well as those cues from the exchange itself. So, for instance, if we snap at a stranger they are more likely to mind-model that we are an angry or rude person, whereas a friend who knows this is unusual behaviour might mind-model that we are upset or having a bad day. These mind-models have consequences for how interactions unfold: the stranger might snap back, our friend might ask what’s wrong. It’s reasonable to suggest that the better we know a person the more chance we have of constructing a mind-model for them that accurately reflects their actual mind, but it’s also important to remember that these models are assembled from our best guesses, and might still be wrong.

This is one reason why exchanges on Twitter can become rife with miscommunications, misinterpretations and arguments, especially if interactants don’t know each other offline: we have very little to go on when constructing a mind-model for the person we’re talking to, sometimes just 140 characters and perhaps a single profile image. This leaves the door wide open for people to be first interpreting another’s comments, and then second constructing their responses, based on a mind-model which does not accurately reflect the other person’s mind. This also applies to tweet exchanges involving questions and answers; mind-modelling can completely transform how a discourse participant interprets a question, and thus how (or indeed whether) they answer. Consider, for instance, how you feel about being asked a question in these two scenarios:

- When you think the person asking is genuinely curious and thinks you may know the answer; compared with,

- When you think the person thinks that you don’t know the answer and is trying to catch you out in order to embarrass or undermine you.

Both of these scenarios involve you mind-modelling the person asking the question because you cannot access their actual thoughts in the way we are often given access to the thoughts of fictional characters. In other words, it’s important to bear in mind that even posing simple closed questions in a classroom can carry a huge amount of mind-modelling baggage.

At a superficial level, we can think about questions as a strategy teachers use in order to calibrate their mind-models for individual students. So, for example, if you think that Jim has understood a particular point or has a particular bit of knowledge, then your mind-model for Jim initially includes this: asking Jim a specific question about this topic is really a way of checking your mind-model against Jim’s actual mind. At the same time, it’s also highly salient to think about what might influence whether and how Jim answers your question, beyond whether or not he is actually able to generate a response.

One of us recently discussed this topic in depth with final year undergraduates, both in relation to their school and university experiences. We started by reading Elliot and Ingram’s fantastic (2016) chapter (available here). Here are some of the insights and reflections that arose from these conversations: it might be interesting for teachers to consider these point in terms of how they might relate to their own practice:

Silence

One thing that became clear from the students’ discussions was that that there can be lots of different types of silence in a classroom following a teacher’s question. The students felt that they were often consciously aware of what kind of silence they were experiencing in a given class and suggested:

- Silence does not always equate to students not knowing the answer, but can be to do with how the students mind-model the teacher’s reason for asking the question in the first place. For example, if I ask ‘has anyone read Catcher in the Rye?’ students might be less likely to say yes if they think that the teacher is asking in order to identify an individual who can then be asked a more specific question about Salinger’s novel (even if this wasn’t the case), because of a concern that they might not know the answer to the unknown question which might follow. A possible consequence of this might be that the teacher then establishes a mind-model for the students which does not include knowledge of the novel when in fact this is not the case.

- Silence can sometimes be the result of students having *an* answer, but not being confident it’s the *right* answer. Here the *right* answer was understood by the students as the answer that they mind-modelled that the teacher anticipated at the point they constructed the question.

- Questions that are framed as open but where answers are then treated as though there is one ‘correct’ response (which they interestingly phrased as ‘open questions that are really closed’) were a key cause of a class’ developing reluctance to answer a teacher’s questions over time. In other words, they suggested that students can develop mind-models of particular teachers which result in the students choosing not to articulate what they otherwise felt would be good contributions to a discussion in case the answer didn’t match the answer they modelled the teacher as having in mind.

Rephrasing

We also discussed how teachers rephrased questions following students’ responses (or lack thereof) and explored how:

- Teachers rephrasing questions can be viewed very positively, as a concession on the part of the teacher that the reason for the lack of response might lie with the presentation of the question rather than a lack of the relevant knowledge in the minds of the students.

- Rephrasing questions can create a stronger sense of negotiation and constructive interaction in the teacher-student relationship because it disrupts the unspoken accusation that the students lack knowledge they should possess.

The status of being wrong or ‘not knowing’

Finally we agreed that the most important factor for productive questioning in the classroom was how students mind-model how the teacher is likely to react to wrong or off-topic answers, or admissions of ‘not knowing’.

Mind-modelling offers a systematic way to think about and describe classroom interactions. As such, we think it could be valuable for teachers to reflect on the way they frame questions through this lens, as well as consider what they base the mind-models they have for their students on, and how reliable or unreliable that information might be.

In the next post we’ll consider how mind-modelling can be usefully applied to practices around marking and feedback.

References

Elliot, V. and Ingram, J. (2016) ‘Using silence: Discourse analysis and teachers’ knowledge about classroom discussion’, in M. Giovanelli and D. Clayton (eds.) Knowing About Languuage: Linguistics and the Secondary English Classroom. London: Routledge, pp.151-61.

Stockwell, P. (2009) Texture: A Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

]]>Mind-modelling (Stockwell 2009)

Rooted in cognitive research on Theory of Mind (Premack and Woodruff 1978), mind-modelling offers a useful way for us to conceptualise how we think about and understand what’s going on in other people’s heads. Theory of Mind is typically associated in popular discourse with autism, but it’s actually got a much broader focus. In essence, having a ‘Theory of Mind’ can be understood as the awareness most humans intuitively – often unconsciously – have that other people have minds of their own, think things, and act and speak as a result of their thought processes. Theory of Mind also includes our knowledge that other people can’t see inside our heads, and that their level of knowledge about a topic or their thoughts might be different from our own. This is where autism comes in, because some people on the autistic spectrum do not have an intuitive awareness of this, and very small children do not have this awareness at all. We can see presence or absence of Theory of Mind being identified empirically through the ‘False Belief Test’, find out more here: https://goo.gl/H5xsHU.

Mind-modelling, a term coined by Peter Stockwell in his 2009 book Texture: A Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading, goes further by applying these ideas to explain how we mentally construct (or ‘model’) our sense of what’s going on in the mind of a character, an animal or another person. Simply put, we have direct access to our own mind and thoughts: everything else is essentially guesswork. In other words, whenever we interact with other entities, real or fictional, human or animal, we ‘mind model’ what we think is going on in their head, and it can be all too easy to forget that this model may be inaccurate. When we do this whilst reading a novel we often do get a window into the character’s mind through various types of ‘thought representation’ (For a good summary of this see here: https://goo.gl/ZJsnWT). In our day to day interactions, however, we’re left to construct our mind models from the other cues we have available, which might include in the immediate context:

- what a person says, their tone and manner;

- a person’s actions;

- facial expressions and body language.

However, we will also draw on the schematic knowledge we bring with us to the interaction. This could include:

- our knowledge of the person and our previous interactions with them;

- our more generic knowledge schemas regarding characteristics such as gender, race, age, clothing, job or role (if known or apparent);

- our knowledge of the context in which the interaction occurs, which could be generic (a classroom) or specific (my classroom).

So in any interaction you have with another person, both of you interpret (mind-model) what you think is going on in the other person’s head based on what you know or assume (consciously or subconsciously) about that person, what they’re saying, and how you interpret their actions.

This is a really useful way of thinking about interactions between teachers and students in the classroom. In the next few posts we’re going to explore mind-modelling and education in more detail, focusing on these three areas in particular:

- questions and answers;

- marking and feedback; and,

- conceptualising the classroom as a discourse space.

References

Premack, D. and Woodruff, G. (1978) ‘Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(4): 515-526.

Stockwell, P. (2009) Texture: A Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

]]>Below is the second essay in this mini-series: a challenging and nuanced exploration of linguistics and social justice, by final year Language and Literature student Isobel Wood (@issywood_ ). Drawing on examples from the recent BBC documentary Tough Young Teachers, which followed new teachers undertaking Teach First – a course which puts excellent graduates into some of the UK’s most challenging schools – as well as a body of research from the US, Isobel explores the value of linguistics, not just as subject content knowledge for teachers, but as an enabling tool to help practitioners reflect on their interactions with students.

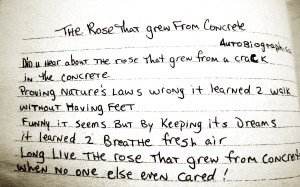

‘Why aren’t we watering the concrete?’: Exploring the value of linguistics and critical pedagogy to the teacher.

(Shakur 1999)

The current education system in the UK and the USA can be effectively explained using Freire’s banking concept. The teacher’s task is often to ‘fill the students with the contents of his narration’, rather than creating a stimulating and useful dialogue with which to cope and view the world (Friere 1970: 52). Drawing upon Tupac Shakur’s metaphor of urban youth as roses growing in concrete, I am going to explore why ‘watering the concrete’, isn’t seen as a priority within the western education system. I will also explore how this can be addressed through using the classroom as a supportive discourse space that equips children with the skills to understand their own position and critically engage with the world around them; rather than the use of education as another form of oppression that is characterised by social class, race and wealth.

Social deprivation

Let’s be honest with ourselves about what our young people are really carrying when they come to us.

(Duncan-Andrade 2016).

In order to understand why children behave the way they do, educators must look to the real lives of the children they are teaching. One of the things that has led me down this route of research is the lack of understanding that some teachers appear to have for children that are simply labelled as ‘naughty’ or ‘disruptive’. Watching Tough Young Teachers in particular led me to question why these teachers are not concerned with establishing the root cause of a student’s behaviour. Exclusion, dismissal or a focus upon punishment rather than rehabilitation is prevalent with all the teachers shown on the programme (BBC 2015). Duncan-Andrade (2010) states that educators need to begin with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in order to successfully understand student behaviour; he claims that if a child is misbehaving, one of their basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, safety) is ‘under attack’.

Consider the following extract from Tough Young Teachers, a recent BBC documentary which followed new teachers on the Teach First programme. You can find out more about Teach First here. A student, Caleb, has been disruptive in the teacher’s lesson:

Teacher: Ultimately there comes a point where, he [Caleb] wasted time in my lesson there you know? I didn’t get through as much as I would’ve done, so he’s disrupting other people’s learning, erm, which isn’t fair. And so, there’s only so much effort that I’m going to put into convincing him that… he’s making the wrong decision.

(BBC 2015)

Here is an example of a teacher dismissing a child, seemingly through a combination of frustration and inconvenience, rather than exploring the reasons behind their behaviour. Within this episode, the teacher does not try to ask the student, Caleb, why he is unwilling to engage. He uses the phrase ‘wrong decision’, suggesting that he believes Caleb’s behaviour is a conscious and obnoxious effort not to engage with his education, rather than assuming that there are underlying causal reasons. The teacher also addresses the issue of ‘wasting time’, highlighting a constraint of the profession whereby a lack of time permits certain children to slip through the cracks.

This next extract shows Caleb’s response following his exclusion from the teacher’s lesson for refusal to participate:

Caleb: I’m just a little yout’ that can’t… I have no say in my life, what happens in my life, so what am I supposed to do? How am I supposed to make a change if I can’t do anything? I have to take orders from next man which is just somebody’s else’s son, just like me another human being with blood flesh and and … tears and.. just like me. And I can’t do nothing about it, ‘cause I’m just a little yout’ that was born couple years ago. Like I don’t have a mind and a heart and shit that I wana pursue in my fucking life as well. Nah fuck that. I’ma do what I wana do, I don’t care about school, I don’t care about nothing. I can do anything I want, I can be anything I want when I’m older. Cos I got them skills. I don’t need nobody. I don’t need no family, no teachers, nothing, I don’t need shit. Cos I can go out there and make way more money than they’re making right now.

(BBC 2015)

The concept of mind-modelling is useful here. Mind-modelling explains that no individual can authentically experience the mental process of another person, suggesting that we use what we know about our own cognitive processes and project them onto another in an attempt to understand their behaviour (Stockwell 2009). These two extracts shown side by side, effectively demonstrate that the teacher has failed to mind-model Caleb’s reasons for his academic apathy. Caleb’s dialogue suggests that he knows he is part of a system that is designed to assist his failure. Caleb comments on his lack of autonomy by claiming, ‘I have no say in my life’, suggesting that he feels there is no point in his academic achievement because his route and outcome have been pre-determined by social bias and oppression. Constantly affirming that he is just like everybody else, Caleb refers to basic physical qualities such as ‘blood, flesh and tears’, suggesting that Caleb feels dehumanised by the system. He makes reference to being ‘just another human being’ and, ‘somebody else’s son’ and goes on to describe more internal qualities such as ‘mind, heart and dreams’, implying that he feels the necessity to assert and explain his humanity; justifying his importance as a human being.

Caleb concludes his speech by demonstrating aspects of the rugged individualist narrative often found in rap music. His comments surrounding his capability of succeeding without help from others, represent the failure of the education system in supporting and encouraging students; and demonstrates how young people like Caleb can become alienated into believing that no one is there for them. He claims that he doesn’t ‘care about nothing’, or need family or teachers, and that he can ‘make way more money than they’re making’, without engaging in the school system, leaving the audience to infer his participation in criminal activity, despite his claim to having ‘them skills’. When questioned in a later episode, Caleb admits that he wants to do well in his GCSEs and expresses that he believes he could get A’s and B’s, but doesn’t think he will. This exchange proves that in reality Caleb knows that his education is important, but doesn’t have faith in his success, regardless of whether or not he tries. This demonstrates the self-fulfilling prophecy of engaging as a failure in a system that is designed to fail you.

Following Duncan-Andrade’s (2010) research, the link must be made between the social conditions of a child’s life and ‘how it’s affecting their bodies’, which in turn, affects their behaviour in the classroom. Considering the sentiments expressed by Caleb, how are students who constantly have to contend with these underlying feelings of oppression supposed to actively engage with a system that they know is structured against their academic and social success? Duncan-Andrade (2010) refers to:

the ‘multiple accumulation of negative stressors’ within a child’s life, but more specifically, day or morning, ‘without the resources to cope’, which manifests itself as disobedience or disruptive behaviour in the classroom.

Instead of excluding children and ignoring their subconscious cries for help, these root causes need to be addressed by rebuilding communities (Canada 2001).

‘…So what, now what?

If urban youth are like roses in the concrete and can grow in spite of severe neglect, then what might the world look like if these youth were given the right amount of nurturing in their homes, communities and schools?

(Kumasi 2012: 35)

Canada (2013) refers to the education system as a business model and questions how a failing model can continue to be applied year after year, where in the cases of profit-led institutions, this would not be allowed to happen. Cases where schools and educators have realised this and began to reform, are unfortunately of the exception. Linda Cliatt-Wayman (2015) describes how she began to rehabilitate the high school Strawberry Mansion in North Philadelphia, that had been on the ‘most dangerous’ list for four consecutive years. She explains that she restructured the school day to incorporate extra subjects that she deemed essential; ‘remediation, honours courses, extra- curricular activities and counselling, all during the school day’, therefore recognising and actively addressing the need for emotional support within the schooling system (Cliatt-Wayman 2015). The Beacon school programme that Canada is involved with, also recognises the need for support and extra-curricular development, supporting the idea that education encompasses more than merely ‘the act of depositing’ (Freire 1970: 52). Canada addresses the fact that children simply deserve opportunities for leisure time and the time to develop different skills, as well as the positive social impact that this time creates:

One critical strategy of the Beacon Schools Program is providing activities designed for adolescents during the late evening and weekends… If we expect our young people to engage in positive activities, we must provide them the places and structure to do so. Leaving thousands of them on street corners with nothing to do only invites trouble (2001).

Here, Canada addresses the reasons behind the creation of street culture and why children become involved in a self-perpetuating cycle of crime, violence, incarceration and/or death. As well as providing physical opportunities for children, Duncan-Andrade (2016) addresses the need for ‘truth and reconciliation’, engaging with the notion that without being truthful about a child’s position in the world, there is no chance for liberation and improvement of conditions. He declares the need to nurture and teach a generation of people who find educational injustice ‘intolerable’, linking to Freire’s claim that ‘the more completely they accept the passive role imposed on them, the more they tend to simply adapt to the world as it is’. (1970: 54). Adapting to the world as it is hasn’t been successful for the current generation of urban youth who are trapped in the concrete. This emphasises the need for social programmes that allow children to break free of their social cycles and be exposed to the truth of their conditions, in order to incite change.

Using the classroom as a discourse space

‘Authentic thinking, thinking that is concerned with reality, does not take place in ivory tower isolation, but only in communication’

(Freire 1970: 54)

Using the classroom as an honest discourse space is a crucial step towards successfully serving students in urban and socially deprived areas. The mere imparting of knowledge ‘by those who consider themselves knowledgeable’, projects ‘ignorance onto others’ which Freire describes as the characteristics of oppression (1970: 53). The act of becoming critically conscious of your own position is liberating in itself and is necessary in order to use education as catharsis, with the end goal of creating social change (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell 2008). In order to do this, an education that is ‘focused on dialogue instead of a one-way transmission of knowledge’, thus subverting education as banking, is necessary (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell 2008). Liberation can be achieved through ‘acts of cognition, not transferrals of information’ (Freire 1993: 60). This can be seen being put into practice by Duncan-Andrade and Morrell as they exemplify their students using ‘critical media literacies for political advantage’, as students decided to call local media outlets following a health and safety crisis in their school. The students compared these conditions to those of a wealthier school nearby; thus demonstrating their willingness to question events and incite social change through the medium of critical linguistic practices; as well as encouraging a critical dialogue within their community (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell 2008: 59). This engagement however, must be done in a way in which the students can relate. Duncan-Andrade and Morrell (2008) exposed their students to literature from different time periods, as well as comparing poetry to rap music, enabling the students to ‘make connections to their own everyday experiences’, challenging the normative system that is ‘alien to the existential experience of students’ (Freire 1970: 52).

Considering hip hop and rap music specifically, this medium is effective in penetrating the divide between education and the real world as it is a politically conscious, linguistic art form that is present in student’s everyday lives. Morrell argues that the use of popular culture can guide students to ‘deconstruct dominant narratives’ (2002: 72). He comments upon the image of rappers as educators and how they see ‘their mission as raising consciousness of their community’ (Morrell 2002: 74). Similarly, the form of problem-posing education that Freire claims opposes the banking concept supports the ‘emergence’, rather than ‘submersion’, of consciousness (1970: 62). By allowing students to become ‘critically literate’, they are able to take these texts familiar and relevant to them, and use them as a ‘lens to examine other literary works’ which thereby transforms the classroom into a discourse space to examine and be critically aware of the world around them (Morrell 2002: 73-74).

It must also be recognised that these skills can be used as tools for social action and are not just ‘a decontextualized skill set’ (Hallman 2009). Hallman’s (2009) data analysis shows that ‘literacy success was largely dependent on recruiting ‘out-of-school’ literacies for in-school learning’. Thus proving that engaging with a ‘multiliteracies framework’ is a positive and necessary step towards watering the concrete (Hallman 2009). It can help lift individuals from their position, with the ultimate goal of raising awareness, improving conditions and lifting the entire community, supporting Duncan-Andrade’s (2010, 2016) view that

‘the purpose of education is not to escape poverty, the purpose of education is to end it’

For many urban youth living in social deprivation, education is their only source of hope for producing better lives for them and their communities. If these issues do not begin to be addressed as a rule in mainstream education, the system can only be seen as ‘morally bankrupt’ (Duncan-Andrade 2010). Educators need to recognise the situations our youth have to contend with and provide a space for them to talk about this, become angry, be critical of the world; while at the same time providing them with skills to critically apply these feelings academically in order to better themselves and create social change. By applying critical pedagogy and using the classroom as an honest discourse space, we can begin to water the concrete. Through education, we can transform the exceptional rose, into collective roses, all of whom can and will succeed within a system that has been re-designed to help and nurture them, rather than curtail their success and ensure their failure.

Did you hear about the roses who

were trapped in concrete?

Given no hope they

suffocated, were incarcerated

by their oppressors, who cut their stems,

starved them, polluted the air.

Where is the hope for the roses

For whom there’s no one there?

But

did you hear about the roses that GREW

from cracks in the concrete?

Proving society wrong they

were helped to stand on their own feet

by their educators, who fed their dreams,

gave fresh air.