| CARVIEW |

It can be difficult to get good lateral (profile) clinical photos of children , especially small ones. Both the photographer and the studio strobes are much more interesting than a parent snapping her fingers. So you have to come up with some distractions to get the child facing in the right direction. Here are two solutions we have found to work well.

PEZ dispensers

These cheap candy dispensers/toys are colorful and fun to look at. If the child is sitting on a parent’s lap, the parent can hold the dispenser in front of the child. If shaken, it even makes a noise as the head part moves. Since they’re made of plastic they’re also easy to disinfect.

CDs

I have had this idea for quite some time, but only got around to testing it recently: CDs hanging from the ceiling. This solution is great for both small and larger children. With the large ones the CDs are something specific to refer to. “Sit this way and look at that CD”. Much easier than ask them to look straight ahead/at the wall. With the smaller children a CD with a spin to it is totally mesmerizing. A moving shiny silver rainbow thingy! After we started using the CDs the toddlers sit still much longer than before. We have put up one on either side of the studio (see photo). They’re hanging from string attached to the light armatures with some old film clips, so they can be easily put up and removed.

Fellow medical photographer Bård Kjersem and I have written an article about the history and current practice of clinical photography at our departments at Rikshospitalet (the National Hospital) in Oslo and Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen.

Fellow medical photographer Bård Kjersem and I have written an article about the history and current practice of clinical photography at our departments at Rikshospitalet (the National Hospital) in Oslo and Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen.

The article is published in Norwegian in the Michael Quarterly journal (open access) of the Norwegian Medical Society. Read it here.

For foreign readers there is an automatic (and sadly not very good) English translation available here.

]]>

Photos by Øystein H. Horgmo © All rights reserved.

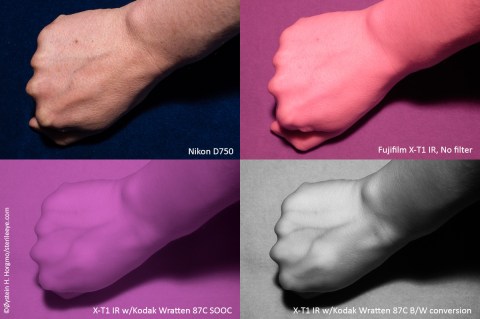

We received the Fujifilm X-T1 IR for testing this week. I did a quick test shoot of the back of my hand to show what it can do compared to a normal camera.

The Fujifilm X-T1 IR captures both infrared, visible and ultraviolet light (380-1000nm). Without any filter on the lens, the image becomes saturated with too much information (top right). The colors are off due to the infrared light. To make use of the camera for medical reflected infrared photography we need a filter that only let the infrared light through. Infrared light penetrates deeper into the skin than visible light, and is useful in medical photography to visualize subsurface structures.

The bottom photos above are the same image straight out of camera (SOOC) and after conversion to B/W. A Kodak Wratten No. 87C filter was used. This filter appears opaque to the human eye, but as the camera sensor captures infrared light, a purple image was visible in the viewfinder/LCD and the photo could be composed with the filter on. The autofocus also worked fine with the filter on, so there is no need for focus shifting. Blood vessels absorb more infrared light than the surrounding tissue and appear dark in the bottom photos above.

The photos were taken with low ISO and small aperture, and the sensor seems impressively sensitive to IR light.

Equipment

- Fujifilm X-T1 IR camera with Fujinon 35mm f/1.4 lens.

- Reference: Nikon D750 camera with Nikkor 50mm f/1.4 lens

- Kodak Wratten gelatin filter No. 87C

- Broncolor minicom 80, uncoated flashtube, protecting glass removed

Settings

- ISO 200

- Shutter: 1/125 sec

- Aperture: f/16

]]>

My department shoots lots of photos for the annual reports of different medical research institutes. For the 2015 annual report of the Centre for Immune Regulation (CIR) I made several conceptual photomontages that were used on the front page and as chapter separators. Check them out above.

I also shot the 2014 report, which can be viewed here.

]]>

Left: Wikimedia Commons. Right: National Museum of Health and Medicine. Creative Commons.

I have published a paper in the Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine called Mirrors in Early Clinical Photography (1862-1882): A Descriptive Study.

Abstract:

In the mid-19th century, photographers used mirrors to document different views of a patient in the same image. The first clinical photographs were taken by portrait photographers. As conventions for clinical photography were not yet established, early clinical photographs resemble contemporary portraits. The use of mirrors in clinical photography probably originated from the portrait studios, as several renowned photographers employed mirrors in their studio portraits. Clinical photographs taken for the US Army Medical Museum between 1862 and 1882 show different ways of employing this mirror technique.

The full article is available at Taylor & Francis Online.

If you are interested in reading the full article and do not have access, please contact me.

Here is an interview with me about the article (in Norwegian).

Here is a blog post on the same subject I posted a few years back.

More photos with mirrors can be found on the National Museum of Health & Medicine’s Flickr-page.

Errata:

Reference 13 is incorrectly attributed to the University of California. The correct reference is:

Pitts T. William Bell: Philadelphia photographer [Master thesis]. Tucson: University of Arizona; 1987:12-25.

The document is available online here.

]]>

Photo: Vidar Ibenfeldt © 2015. Used with kind permission.

Last weekend I attended the Norwegian Institutional Photographer’s annual conference in Bergen. The most interesting happening was a reenactment of what must be one of the first instances of standardized medical photography in Norway.

In the mid 19th century leprosy (also known as Hansen’s disease) was spreading on the west coast of Norway. The growing number of patients made the government put more money into research. Dr. Gerhard Armauer Hansen was leading much of this research. The disease was named after him as he was the first to identify the leprae bacterium.

I the autumn of 1884 the French dermatologist Henri Leloir visited Bergen to document the state of leprosy in Norway. In addition to written reports, he used photography to document some of the patients. Back in Paris he published his exclusive monograph “Traité practique e Théorique de la lépre”. 11 of the Norwegian patients he met in Bergen are represented with photos in his book (the photos can be seen from page 345).

The common way to represent examples of disease at the time was engravings made from paintings. An example of this when it comes to leprosy, is the Norwegian book “Om Spedalskhed” (On Leprosy) by Daniel C. Danielssen and Wilhelm Boeck, published in 1847. Several of the engravings from this book can be seen in the excellent The Sick Rose – Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration by Richard Barnett.

We must assume that Leloir’s modern documenting methods impressed Armauer Hansen, for just after Leloir had left Bergen, Hansen wasted no time to get new photos taken of the same patients. The poses, light and distance to the camera was exactly the same as Leloir had used. As far as we know it was the Norwegian photographer Marcus Selmer who took the new photos (Sandmo 2006). We think that this is one of the first attempts to standardize the photography of a medical condition in Norway.

And on April 11 in Bergen, Bård Kjersem, photographer with the Department of Ophthalmology at Haukeland University Hospital, reenacted this using a wooden 4×5 inch camera, a model made up as a lepra patient and a colleague, with a beard as impressive as Armauer Hansen’s, standing in as him.

The resulting photo can be seen below, fixed to an authentic journal note from the 1880s.

]]>I have always used to auto focus by pressing the shutter release half way down. Focus, re-compose and shoot. But six months ago I tried changing to back button focusing, after watching the video above. I haven’t gone back.

The video explains the concept very good. But in short, by assigning auto focus to another button than the shutter release you gain much more control over the focusing. When set up right you can switch between all focus modes instantly without changing any camera settings.

You set up the camera so the auto focus is triggered by a button on the back of the camera. On Nikon cameras (which I use), this button is called “AF-ON”. When shooting, you operate it with your thumb.

When the auto focus no longer is triggered by the shutter release, you don’t have to re-focus after each shot anymore. You only have to focus and re-compose once, since the camera will not re-focus when you press the shutter again. But that’s just for single auto focus. With this set-up it is also much easier to switch to continuous auto focus and manual focus. Here’s how:

Single auto focus (AF-S): Press and hold the AF-ON button until you have the desired focus. Release the AF-ON button and the focus is locked. It stays locked until you press the AF-ON button again.

Continuous auto focus (AF-C): Press and hold the AF-ON button.

Manual Focus: With the lens focus switch set to M/A, you can manually focus the lens when you don’t press the AF-ON button.

It takes a while to get used to focusing like this, and I guess it’s not for everyone. But I find it ever more useful. For example, when photographing small children in the studio, it is very useful to be able to switch between single and continuous auto focus swiftly.

This is what you need to do to set up your Nikon DSLR for back button auto focus:

1. Set the focus mode to continuous (AF-C)

On professional models this is done with a switch on the side of the lens. On smaller models this is done in the i-menu.

2. Change the auto focus activation to AF-ON only.

This is done in the menu. Go to Custom Setting -> Autofocus -> AF activation -> AF-ON only.

Thanks to Petapixel for pointing me to the video six months ago.

]]>

Photo by Kathy Phillips, U.S. National Archives. Public domain.