| CARVIEW |

A little over a month into the Trump administration, I’m fighting a moral fatigue that comes from the relentless onslaught of outrages. My fatigue is moral because the goals and actions of this administration are so antithetical to my core values. What looks to Donald Trump (and many of his supporters) as a return to greatness looks to me like one of the circles of hell – not a world I want to live in.

A little over a month into the Trump administration, I’m fighting a moral fatigue that comes from the relentless onslaught of outrages. My fatigue is moral because the goals and actions of this administration are so antithetical to my core values. What looks to Donald Trump (and many of his supporters) as a return to greatness looks to me like one of the circles of hell – not a world I want to live in.

The values I see in Trump’s version of greatness are “strength” defined as meanness, bullying and domination, and “America First” defined as selfishness, greed, acquisitiveness, and, again, domination. In contrast, I am committed to trying to create a world in which we treat one another with kindness, generosity and mutual respect. The contrast between President Trump’s values and my own are exemplified by his proposal to “clean out” Palestinians from Gaza so that it can be redeveloped into a for-profit playground for the rich. This vision, which strikes President Trump as “magnificent,” strikes me as obscene. If Trump is a mean bully, his sidekick, Elon Musk, seems to delight in cruelty. I am sickened by the richest man in the world, via a stop-work order, preventing life-saving nutrition already on the ground from being administered to starving babies (literally taking food out of the mouths of babies) and then bragging about it on X, saying that he could have spent weekend time going to “some nice parties” but “did this instead.”

For those of us who are appalled by the casual cruelty of sentencing starving infants to death as an alternative to partying, an important question is how to effectively resist. I am what social psychologists call an “instrumental coper,” which means that I cope with stress by taking action. Just tuning out is not an option for me. But what can I do? I am focusing my efforts on what I can do locally, where it seems as though I can make more of a difference. I am proud of my governor, Janet Mills, for standing up to Trump’s bullying at a recent White House meeting for governors.

In the face of all the organized inhumanity around us, I am prioritizing keeping my own humanity, leaning into those values of kindness, generosity and mutual respect. I am happy that my corner of the country is still a place where most people are kind, welcoming, trusting, and willing to help strangers, and I’d like to keep it that way. I’m encouraged by the fact that when a local refugee resettlement agency suddenly had its federal funds cut off, local people stepped up to help. Being a refugee is one of the few legal pathways available for immigration to the United States. The process is a grueling one in which refugees undergo a years-long vetting process. Once they are accepted for resettlement in the United States, they are granted a ninety-day resettlement period, during which they get help with food, finding housing, finding employment, getting children enrolled in school, etc. Local resettlement agencies provide the actual resettlement help, but the federal government normally provides funds to support that assistance. When our local agency found themselves without that funding, but with 110 recent refugees in their care, many of us made donations to try to replace some of the lost federal funds. Others volunteered their time to help with housing and job searches, with transportation and with school enrollment. Some even opened their homes to provide temporary housing for newly arrived refugee families. That’s the kind of world I want to live in.

One of my strategies for resisting without becoming overwhelmed is to pick my battles. I can’t take on every outrage of the new administration, so I am focusing on those I particularly care about (like welcoming immigrants) or where I have skills or expertise to contribute. As an educator, I have gotten involved in several efforts, mostly through my local Senior College, to create opportunities for mutually respectful conversations between those who disagree, about issues that divide us. As a social scientist, I know a lot about data; so, when I learned that Musk was putting resignation pressure on local U.S. Census Bureau field representatives, I got in touch with Senator Susan Collins, drawing on my expertise to warn about what it would mean to lose the high-quality data these federal workers collect for us.

As I look for opportunities to resist effectively, I also know that I need to take care of myself. While it is important for me to keep in touch with what’s happening, I also need to take breaks. Spending time out in the natural world, choral singing, curling up with a good novel, or just bingeing on some escapist TV are all ways for me to do this. When I find myself doom scrolling, I can get up and walk away from the computer and take a “joy break” by going outside or just enjoying the views from my windows.

I remain hopeful that we will somehow get through the current insanity and the United States will once again become a country I can be proud to call my own.

]]> For as long as I can remember, I have loved food. Like most children, I had some foods I didn’t like; but I was a kid who didn’t have to be called to the dinner table twice and who usually ate what was put in front of me enthusiastically. Seven decades later, I’m still enthusiastic about food. And, unlike many of my single friends, I enjoy cooking for myself. The cooking I do isn’t fancy; my preference is for fresh, whole foods, simply prepared.

For as long as I can remember, I have loved food. Like most children, I had some foods I didn’t like; but I was a kid who didn’t have to be called to the dinner table twice and who usually ate what was put in front of me enthusiastically. Seven decades later, I’m still enthusiastic about food. And, unlike many of my single friends, I enjoy cooking for myself. The cooking I do isn’t fancy; my preference is for fresh, whole foods, simply prepared.

I was already buying much of my produce directly from farmers at local farmers’ markets when I was inspired by Michael Pollan’s In Defense of Food (Penguin, 2008) to focus much more intentionally on eating fresh, whole foods. But it was Barbara Kingsolver’s wonderful memoir, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle (HarperCollins, 2007), a Christmas gift from a friend, that inspired me to become a locavore, someone who builds their diet around local foods. I remember the delight with which I searched the directory at localharvest.org (now sadly out of date) for farmers markets, CSAs, farmstands, and local farmers selling items like eggs and hand-crafted cheeses.

Being a locavore is not so much a diet as a lifestyle, and one of my favorite aspects of the locavore lifestyle is that eating locally means eating seasonally. Each season, I rediscover favorite dishes that I haven’t eaten in many months. Recently, for example, I’ve been enjoying butternut squash galette, made from a recipe that I downloaded from a fellow blogger’s website more than a decade ago. I forget how much I love this meal until local butternut squash becomes available again in late fall and winter. Some of my seasonal foods, like my annual farm-fresh turkey, have taken on the status of rituals. Each Christmas, I spend days preparing a big turkey feast that includes not only a local pasture-raised turkey, but fresh cranberry sauce made from locally grown cranberries, local potatoes, rutabaga, butternut squash, and salad greens, dinner rolls made from Maine grown and milled whole wheat flour, and apple pie made from local apples. After this sumptuous feast is over, I spend several more days packaging leftover turkey, along with gallons of homemade turkey stock and turkey soup, for the freezer.

Maine has a long winter, during which not much local food is produced (although a surprising number of farmers grow cool weather crops like greens and root vegetables in polytunnels during the winter). This year, I’ve discovered the Brunswick (Maine) Winter Market, which is held every Saturday morning in an old mill building. I went for the first time the Saturday before Christmas and found the crowds a bit overwhelming. But there was also an amazing variety of foods for sale – not just fresh produce, but also dried beans, seafood and meats, eggs and cheeses, breads, and specialty products like spices and vinegars. Brunswick is about 25 miles away from my home and is the location of the retirement community that I expect to move to in a few years. I plan to visit the winter market once or twice a month through the winter, providing me with not only great local food, but also an opportunity to get to know the community where I will one day be living.

Not all my dietary needs can be met by the winter market. Part of my locavore lifestyle is preserving freshly harvested food for winter eating. This begins in July, when the first garlic and basil is harvested and I make pesto for the freezer. I freeze wild Maine blueberries in August, and I can tomatoes in September. Bell peppers (both green and red) get sliced and frozen in quart bags in late summer and fall, followed by pureed pumpkin and squash in late fall and, of course, all that turkey in December. At this time of year, my freezer is jam-packed with plenty of good local food to see me through the winter months. By the time the freezer is almost empty in late spring, the local farm season will be starting up again, and it will be time for me to rediscover all those early season foods that I love.

]]>Interactions with my students were not the only prompts for updating my self-image. Family funerals could have a similar effect. I was twenty-seven when the last of my grandparents, my mother’s mother, died. I remember sitting in the pew a couple of rows behind my grieving mother and aunt and thinking, “They’re the older generation now and we (my siblings and cousins and I) are the grown-ups.” I didn’t feel ready to be a grown-up.

By the time of my mother’s funeral, thirty-five years later, I felt completely comfortable in the role of grown-up. At age sixty-two, I was a successful professional, a respected college professor who commanded a classroom with ease and had decades of experience chairing academic departments and faculty committees. I felt confident in my ability to handle pretty much anything life threw at me. But it was time for another self-image update as I realized that my siblings and I were now the oldest generation in the family.

Fast forward another fifteen years. In the past fourteen months, two of my four siblings have died. This, combined with my unexpected hospitalization in the summer, has triggered another self-image update. I am now trying to get comfortable with the fact that I am old. Not old in the sense of being frail or feeble or unable to do the things I want to do, but old as in not having all that much of my life still ahead of me. It is now strikingly obvious that my contemporaries and I are not immortal. I have become part of the generation who open the local paper each morning to the obituaries to see if anyone we know has died, and I am repeatedly surprised to find that most of the people in those obituaries are my age or younger. Not only do the number of years I have left to live feel surprisingly small, but those years are whizzing by at a shockingly rapid rate. (How can it already be 2025??)

The fear of death and negative associations with the word “old” are so powerful in our culture that it is tempting to run screaming from any suggestion that I might be old. But I think that embracing this identity can help me to recognize that every moment remaining in my life is precious and prompt me to try to live each precious moment as fully and joyfully as possible.

]]>On a Sunday morning, when I had just finished my breakfast and was getting ready to go out to the farmers’ market, I felt a strong heart palpitation followed by a fairly severe wave of dizziness. Once the worst of the dizziness had passed, I ran through the mnemonic for determining if you’re having a stroke (Balance, Eyes, Face, Arms, Speech, Time is of the essence) and decided that wasn’t it. But something had happened, and because this was the second such episode in a week, because I am in my mid-seventies and live alone at the end of a rural dirt road, because I have a family history of cardio-vascular disease, and because I continued to feel vaguely “strange,” I knew that it would be stupid to ignore this. Calling 911 seemed like an overreaction, but waiting until my doctor’s office opened the next day seemed like an underreaction. So, instead of going to the farmers’ market, I took myself over to the ER to be checked out. Although my blood pressure and heart rate were high, my EKG and other vital signs were normal. By early afternoon, it looked like I would be discharged home with instructions to follow up with my doctor; we were just waiting on the results of a critical blood test. But when those results came back, they indicated that I had had a heart attack. The ER doctor explained that they would need to do this same blood test again after two hours, and the results would determine what happened next. When the second blood test came back, the indications for a heart attack were even stronger. I was given an aspirin and put on a heparin (blood thinner) drip, while the ER staff made arrangements to transfer me to a bigger hospital with heart catheterization capability. A couple of hours later, I was in an ambulance en route to the larger hospital, where I was admitted just before midnight, about twelve hours after I’d first presented myself at the ER. I spent three days in the hospital, where it was affirmed that I had indeed had a mild heart attack but where a heart catheterization happily did not find any blocked arteries that may have caused that heart attack. I was discharged home with some new medications, a follow-up appointment with a cardiologist and a referral to cardiac rehab.

Once I knew I was going to be admitted to the hospital, all kinds of logistical issues presented themselves. First I got in touch with my younger sister in another state; she is my emergency contact, and I wanted her to hear what was happening from me before she got some kind of official call from a hospital. Then I got in touch with a local friend who who is always reliable and willing to help and asked her if she could come to the ER, get the keys to my house, and go there to gather some things I would need for a hospital stay. While I was waiting for her, I made a list of what I needed and where it was located. By the time, I left the ER for the ride to the other hospital, I was in possession of a tote bag full of all kinds of useful things like toiletries, clean underwear, my e-reader and laptop.

The next morning, while I was waiting around to get scheduled for a heart catheterization, I booted up my laptop, logged on to the hospital Wi-Fi, and got to work activating my support network. I sent out a group email to about ten Maine friends, letting them know where I was and why, and with a list of things I might need help with – including getting my car home from the parking lot at the ER and getting myself home when I was discharged from the hospital. The offers of help were pretty much instantaneous. One friend called me at the hospital to get dibs on driving me home upon discharge. Two other friends, one of whom had a key to my house and access to a spare car key, picked up the car from the ER and put it back in my driveway. While they were at my house, they picked up two charging cords I was missing (one for my cell phone and one for my e-reader), and one of them came with her husband to visit me at the hospital that afternoon (on the pretext that they were doing an errand nearby) and brought the cords. Another friend helped me to solve the puzzle of how to get groceries bought and into my house in the week after I got home, when I wasn’t allowed to lift anything weighing more than ten pounds.

This was a good trial run of my solo aging support network. My friends were very responsive, and I had multiple volunteers for each need. But, on this occasion, I was easily able to activate my network myself and organize what needed to be done. Indeed, organizing help gave me something to do while I waited for my catheterization and helped me to feel more in control and less anxious.

But what would happen if I were more seriously ill and not able to make phone calls and send emails? Thinking about the steps I took to activate my solo aging support network made me realize that there are gaps in my arrangements. If my sister, hundreds of miles away, got a call that I was hospitalized, how would she activate that network? In the weeks ahead, I plan to add several local friends to the list of those with whom my medical information can be shared. I also intend to create a list for my sister of my local friends with their contact information. I’m also considering one friend’s strategy of having a pre-packed bag of things she would need in the hospital.

All in all, I consider this a successful trial run of my solo aging supports. All my needs were met, and I now have information I can use to make those arrangements even better.

]]>In the aftermath of those tragic events, I feared that we might lose that sense of community. I worried that people would become distrustful and hypervigilant, turning to guns and violence to protect themselves rather than being willing to depend on the kindness of strangers. This week, I had an experience that reassured me that the community of helpfulness I so value is still alive and well.

When I got in my car to drive to the Lewiston Farmers’ Market on Sunday, the tire pressure warning light came on. I pulled back into my driveway, got my little air compressor out of the back of the car, and discovered that one of my tires had very low pressure. Since only one tire was low, it seemed likely that this was caused by some kind of puncture. I filled the tire with air and drove the eight miles each way to the farmers’ market and back without the warning light coming back on. I hoped this meant the leak was a slow one and that I could wait a few days to get it fixed, because I had a busy week scheduled of providing transportation to multiple medical appointments for both a friend and myself.

When I got up Monday morning, however, I could see that the tire was almost flat and that taking care of it could not be put off. I spent some time arranging alternate transportation for my friend to the hospital for a medical procedure that could not be postponed, did a little research online to prepare for the possibility of buying new tires, filled the tire with air one more time, and took myself off to a tire shop about 5 miles from my house. When I got to the tire shop, it was clearly very busy. The manager was juggling supervision of technicians, a constantly ringing telephone, and a line of customers waiting for service.

I worried that the shop would not be able to fit my tire problem into their busy schedule, but when I got to the front of the line, the manager was kindness itself. He explained that he was short-staffed and wouldn’t have anyone available to look at my tire until mid-afternoon. When I replied that I would wait, he said, “I hate to see you waiting here all that time. Can’t you go home and come back later?” I explained my concerns about driving on the tire, and he reassured me that I should be able to manage the ten-mile round trip without any problem.

Three hours later, having gotten some chores done, eaten my lunch, and topped off the tire with air one more time, I presented myself back at the tire shop. It wasn’t long at all until the technician assigned to my car came into the waiting area, showed me the small nail that he had removed from my tire, explained that he had been able to plug the puncture, and said, “You’re all set. Your car is just outside and the keys are in the cup holder.” “Don’t I need to pay someone first?” I asked. He just smiled and repeated, “You’re all set.”

This isn’t the first time that an auto shop in Lewiston-Auburn has done a small repair on my car free of charge. (See Why I Want to Retire in Maine.) Each time, the experience leaves a smile on my face and a spring in my step as I marvel at the kindness of the community of strangers that I am privileged to be a part of.

]]> Just when we thought winter was over in Maine, we were visited by a rare April nor’easter with more than a foot of heavy, wet snow, high winds, and widespread electrical power outages. In my rural location, storm-related outages typically last for days rather than hours. And no electricity not only means no lights, no heat, no television and no internet; it also means no running water.

Just when we thought winter was over in Maine, we were visited by a rare April nor’easter with more than a foot of heavy, wet snow, high winds, and widespread electrical power outages. In my rural location, storm-related outages typically last for days rather than hours. And no electricity not only means no lights, no heat, no television and no internet; it also means no running water.

Although I wasn’t looking forward to winter’s return, we had a week’s warning that this storm was coming, and getting ready for a big storm brings out a certain pioneer spirit of self-sufficiency in me. I needed to be ready for two or three days when I would be without electricity or water and when it was likely I would be unable to drive out of my rural dirt road. In the week leading up to the storm, I took advantage of bare ground and some mild spring weather to make a start on spring garden chores before the garden was once again buried under snow. Then, in the two days before the storm, I started preparing in earnest. I did some errands, including grocery shopping. I baked a loaf of fresh bread and cooked meals with leftovers that could be reheated for dinners during a power outage. I brought in firewood from outside that I could use in my woodstove for heating and cooking.

My house’s big woodstove in the basement, with a chimney coming up through the center of the house provides a pretty good approximation of central heating and makes it possible for me to get through an extended power outage without a generator. On the afternoon before the storm, I lit the stove to let it get warmed up before the electricity went out. I also charged up my e-reader, two battery-operated lights, and my cell phone. I filled containers with fresh drinking water, and I baked apple crisp for desserts.

When I went to bed, snow was just beginning to fall. At about 3:30 a.m., I was awakened by electricity flickering off and on; a few minutes later, it went out for good. By the time daylight came and I got out of bed, I had a plan for how to manage: I stoked the woodstove and then filled a saucepan with water for washing and put it on the stove to heat. I have an old set of three nested mixing bowls that are medium, large, and very large. I filled the two larger bowls with warm water and placed one in the bathroom sink for washing hands and the very large one in the shower to be used for a sponge bath. I realized that the just-around-freezing temperatures that made the snow so heavy and wet, bringing down trees and power lines, were also good temperatures for storing perishable food outdoors, so I opened the refrigerator once, took out all the food I would need for the next two days, and put it in a cooler out on the screened porch.

By mid-morning, I realized that, because the snow had such high water content, I could melt it down. I took my two largest metal pots, packed them full of snow, and put them on the woodstove to melt. I wouldn’t use this snowmelt for drinking, but it was perfect for filling toilet tanks or for washing dishes. When I noticed just how long it took the packed icy snow in those pots to melt, I realized that I could also use it to keep the refrigerator cold; so I emptied the two crisper drawers, packed them with icy snow, and put them back in the refrigerator.

On the afternoon of the second day without electricity, when I learned that Central Maine Power was estimating that our power would be restored by 10 p.m. that evening, I was feeling pretty smug about how well my pioneer spirit of self-sufficiency had carried me through two days without electricity. But when power was restored to most houses around our neighborhood, the five houses on my dirt road remained in the dark.

By the morning of the third day, my pioneer spirit was sagging. Both my cell phone and one of my battery-powered lanterns had run out of charge, and I was just about out of drinking water. I packed up multiple water containers in a backpack, walked over to the house of a neighbor who has a generator and who therefore had partial power and asked if I could fill water containers and plug in my phone and a lantern battery to charge. She was, of course, glad to help. I came home with 4 gallons of fresh water and promised to return later for my charged devices. In the afternoon, I decided to brave the drive out through several inches of icy slush to go the the local library, where I could plug in my computer, recharge it and my e-reader, and access the internet. Our little town library is a lovely port in a storm. Not only was I able to catch up on e-mail, charge devices, and check some things on the internet; I was also able to commiserate with other storm refugees hanging out at the library. And the librarians even served cookies!

I came home with my spirits lifted, especially since the power company was now estimating that our electricity would be restored at 6:30 p.m. I decided to delay cooking dinner until after the power came on. But when 6:30 p.m. came and went without electricity, I checked the company website on my recharged phone, and discovered that they had pushed back their estimated restoration time to 10 p.m. on the following night. I went to bed feeling decidedly grumpy and with my pioneer spirit in tatters.

Lying awake in the early hours of the morning, I no longer felt any confidence in the power company’s estimates of when our electricity would be restored; it seemed wisest to prepare for several more days without power – a discouraging prospect. If I was going to get out of bed and face another day (or two or three) without the modern conveniences that electricity provides, I needed an attitude adjustment! I reminded myself that, for many years, my favorite vacations had been weeks-long camping trips where I slept in a tent, lugged water from a central location to my campsite, and cooked outdoors on a camp stove. Think of this as like a camping trip, I told myself, only more comfortable – camping with a real bed to sleep in and a roof over my head. Having thus reframed the situation from disaster to adventure, I got out of bed with renewed energy, stoked up the woodstove, heated water for washing up, gathered up more icy snow from the front deck for keeping the refrigerator cold, and set about my day.

In the early afternoon, hours before the power company’s latest estimate, I looked out the window to see a bucket truck on my dirt road; and a few minutes after that, the electricity came back on and life returned to a 21st century normal.

]]>Although I have mostly neglected this blog in 2023, the end of the year seems an apt time to look back on the highs and lows, the gains and losses.

The big loss of the year was the death of the first of my siblings in October. At this stage of my life, I have to be prepared for such losses, but I suppose I assumed that we would die roughly in the order that we were born – oldest first. Instead I received word in early October from a nephew in Florida that my younger brother, ten years my junior, had been taken to the ER by ambulance after collapsing at home and was now in the ICU. At first, it appeared that he had suffered a mild stroke with no permanent brain damage; but the stroke turned out to be the least of his problems. Doctors quickly discovered that he was suffering from a massive infection that had probably begun in his mouth, gotten into his blood stream, and traveled from there to his heart, lungs, brain, and spleen. Although the doctors tried valiantly to get him stabilized so that they could operate on the heart valves that had been damaged by the infection, it was not to be. One by one, his organs began to fail, and he was dead by the end of the month.

The big loss of the year was the death of the first of my siblings in October. At this stage of my life, I have to be prepared for such losses, but I suppose I assumed that we would die roughly in the order that we were born – oldest first. Instead I received word in early October from a nephew in Florida that my younger brother, ten years my junior, had been taken to the ER by ambulance after collapsing at home and was now in the ICU. At first, it appeared that he had suffered a mild stroke with no permanent brain damage; but the stroke turned out to be the least of his problems. Doctors quickly discovered that he was suffering from a massive infection that had probably begun in his mouth, gotten into his blood stream, and traveled from there to his heart, lungs, brain, and spleen. Although the doctors tried valiantly to get him stabilized so that they could operate on the heart valves that had been damaged by the infection, it was not to be. One by one, his organs began to fail, and he was dead by the end of the month.

My brother had moved to Florida as a young man, and that was where he spent his adult life and raised his children. I saw him infrequently during those decades, but we always enjoyed one another’s company enormously when we had an opportunity to visit, and in between, we kept in touch through sporadic email exchanges. I was very grateful to his adult children for asking me to draft his obituary, which gave me a chance to revisit memories and process my grief by exploring all the things I loved about my brother. Early in the New Year, I will travel to Florida with other siblings to participate in a Celebration of Life on the occasion of what would have been my brother’s 66th birthday.

Although they were tiny in comparison with the loss of my brother, I experienced other losses in 2023. One of these was a loss of confidence in my driving after a second car crash in less than a year. Neither of these accidents was my fault: In the first, I was rear-ended by a distracted driver while driving on a country road; in the second, the front of my car was hit while I was stopped at a stop sign by an inexperienced driver who misjudged a turn at the intersection. Still, I now face even short drives with some trepidation. I also lost the joy of choral singing for most of 2023, a result of my decision to sit out the 2022-23 season due to risks of contracting Covid.

Fortunately, my losses were at least partially offset by many gains in 2023. As someone who lives alone, I am always aware of the dangers of social isolation, especially in winter. In winter 2023, to compensate for the loss of weekly interactions with my choral singing group, I joined a book group at my local library and gained new relationships and thoughtful monthly discussions of books I wouldn’t have otherwise read. Although I’ve gone back to choral singing this year – another gain! – I intend to hang onto the pleasures of participating in this book group. I also gained new friends this year, mostly through my participation in the Lewiston-Auburn Senior College, and rekindled my relationship with a childhood friend whom I had not seen in more than fifty years. I gained new neighbors when a young couple bought the house next door to mine, and I am enjoying the pleasures of getting to know them. I also gained new ways to contribute to the community when I got involved with a Maine initiative on solo aging and when I took on a new volunteer role helping a disabled woman who lives alone and is at risk of social isolation.

Some of my gains are cyclical or seasonal, coming back around each year. Right now, I am looking with great satisfaction at a freezer full of delicious food to see me through the winter, the result of preserving the bounty of fall’s harvest and of my annual orgy of cooking around the Christmas holiday. My garden is always a source of seasonal pleasures and gains. This year, I gained many new plants, including a gazillion seedlings from native columbine seeds that I gathered and sowed. I also gained a whole new planting when I undertook the renovation of an old, tired flower bed at the back of the garden.

I am looking forward to gaining new pleasures, new experiences, and new relationships in the New Year. Here’s hoping that the gains of the coming year outweigh the losses that are inevitable at this stage of life. Happy New Year!

]]> I had already been thinking about how gun violence in the United States is related to trust and fear before I read Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World (HarperCollins, 2020). It seemed to me that guns were part of a circular, mutually reinforcing relationship with distrust of others, especially strangers. Those who feel they are surrounded by strangers they cannot trust are much more likely to feel that they need a gun to protect themselves from those dangerous strangers. At the same time, the increasing prevalence of guns can lead us to feel as though those around us are dangerous and cannot be trusted. And, when people feel threatened by others, the presence of a gun makes it more likely that deadly violence will ensue. In Maine this year, for example, two brothers (18 and 22) got in an argument when the older brother wore the younger brother’s t-shirt without permission. When the owner of the t-shirt couldn’t get satisfaction from his brother, he went and got his father’s gun. When the smoke cleared, the father of the feuding brothers had been wounded and the two-year-old daughter of the older brother was dead. I can’t help wondering how the younger brother would have expressed his frustration and rage if a deadly weapon had not been readily available.

I had already been thinking about how gun violence in the United States is related to trust and fear before I read Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World (HarperCollins, 2020). It seemed to me that guns were part of a circular, mutually reinforcing relationship with distrust of others, especially strangers. Those who feel they are surrounded by strangers they cannot trust are much more likely to feel that they need a gun to protect themselves from those dangerous strangers. At the same time, the increasing prevalence of guns can lead us to feel as though those around us are dangerous and cannot be trusted. And, when people feel threatened by others, the presence of a gun makes it more likely that deadly violence will ensue. In Maine this year, for example, two brothers (18 and 22) got in an argument when the older brother wore the younger brother’s t-shirt without permission. When the owner of the t-shirt couldn’t get satisfaction from his brother, he went and got his father’s gun. When the smoke cleared, the father of the feuding brothers had been wounded and the two-year-old daughter of the older brother was dead. I can’t help wondering how the younger brother would have expressed his frustration and rage if a deadly weapon had not been readily available.

Murthy’s book provides a broader framework for understanding all of this. He roots his analysis in an evolutionary theory of loneliness developed by the social neuroscientist John Cacioppo which argues that “humans have survived as a species not because we have physical advantages like size, strength, or speed, but because of our ability to connect in social groups” (p, 29) and that loneliness “serves as a signal to attend to and take care of the social connections that define us as a species.” (p. 32) Feeling disconnected from others can trigger a whole host of emotions, including anger, fear, and alienation, but it almost always produces a hypervigilance that makes us extra-alert to possible threats. Murthy notes that this response to social disconnection is built into our biology:

Over millennia, this hypervigilance in response to isolation became embedded in our nervous system to produce the anxiety we associate with loneliness. When we feel lonely, our bodies still react as if we were lost on the tundra surrounded by wild animals and members of alien tribes.” (p. 38)

Although this response to disconnection may be “as old as humanity,” he argues, “the current moment feels like an important inflection point.” (p. 97) He points to the paradoxical influence of modern technologies that promise to make it easier to connect with others but often have the unintended consequence of making us more disconnected. Many of us have observed couples dining in a restaurant who are ignoring one another while interacting with their screens. Similarly commonplace are scenes of children in public places desperately trying to get their parents’ attention while the parents are focused on their phones. Those who get sucked into the clickbait features of social media may spend more time alone in front of their screens and less time with others. And we’ve seen how the dissemination on social media of misinformation and memes intended to stoke outrage can produce anger, incivility and greater distrust of those who disagree with us.

Into this setting in which increased social disconnection was already a problem came the Covid-19 pandemic. As the virus spread and people died, we learned that just being in the presence of other living, breathing human beings could threaten our lives. We were advised so adopt “social distancing” to protect ourselves. In his regular press briefings during the early months of the pandemic, our Maine CDC Director, Dr. Nirav Shah, pushed back against the term “social distancing,” saying that our goal should be to keep physical distance between us while staying socially connected. To some extent, we could use telephone calls and group Zoom conferences to keep us connected with others. But, in the end, all the actions intended to keep us physically safe did make us more socially isolated. Living alone in my house in the woods at the end of a rural dirt road, I remember feeling as though the solitude that I normally thrive on had turned into solitary confinement. When I did go out to public spaces, I worried about how careful the strangers around me were being about Covid and whether they were a threat to me. In other words, I didn’t trust them. I remember one Sunday in the first summer of the pandemic when I had a near-meltdown because the woman pumping gas on the other side of the pump from me (less than 6’ away) was not wearing a mask.

Given Dr. Murthy’s analysis of loneliness and its effects, it probably should not surprise us that gun sales went up dramatically during the first year of the pandemic. Studies using data from FBI background checks found peaks in March 2020, when the global pandemic was first declared and closures of schools and businesses began, and in June, 2020, the month when protests triggered by the murder of George Floyd were at their height. Most of these gun purchases were made by people who already owned guns and were beefing up their protection in response to a heightened sense of threat, but more than 20% of purchases were made by people who had not previously owned guns.

As the “public emergency” of the pandemic has ended and we are learning to live with Covid-19, are we getting back to pre-pandemic levels of social connection? My own sense is that the social disconnection created by the pandemic is not so easily undone. I know I am not alone in continuing to be wary of strangers in public places who may or may not be shedding the virus. All around me, I see signs of negative emotions that may well be a response to social disconnection: I see more aggressive driving since the pandemic; I am nonplussed by how frequently I am passed in no-passing zones by impatient drivers on winding two-lane country roads, despite the fact that I am driving faster than the speed limit. We also see a general quick-to-anger response (e.g., at contentious school board meetings) from citizens who no longer trust public institutions. And an out-of-control sense of threat seems like the best explanation for the recent spate of shootings triggered by innocent actions like knocking on the wrong door or pulling into a stranger’s driveway to turn around.

Murthy argues that social disconnection and loneliness have reached such proportions that they should be treated as a public health emergency. His recent report Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community devotes a chapter to “A National Strategy to Advance Social Connection,” based on six “pillars” of strengthening social infrastructure in local communities, enacting pro-connection public policies, mobilizing the health sector, reforming digital environments, developing a national research agenda that will deepen our knowledge of social connection and disconnection and their consequences, and cultivating a culture of connection. I recommend both Murthy’s book, which helped me to better understand our fraying social bonds, and the report, which provides practical advice about what we can do to make things better.

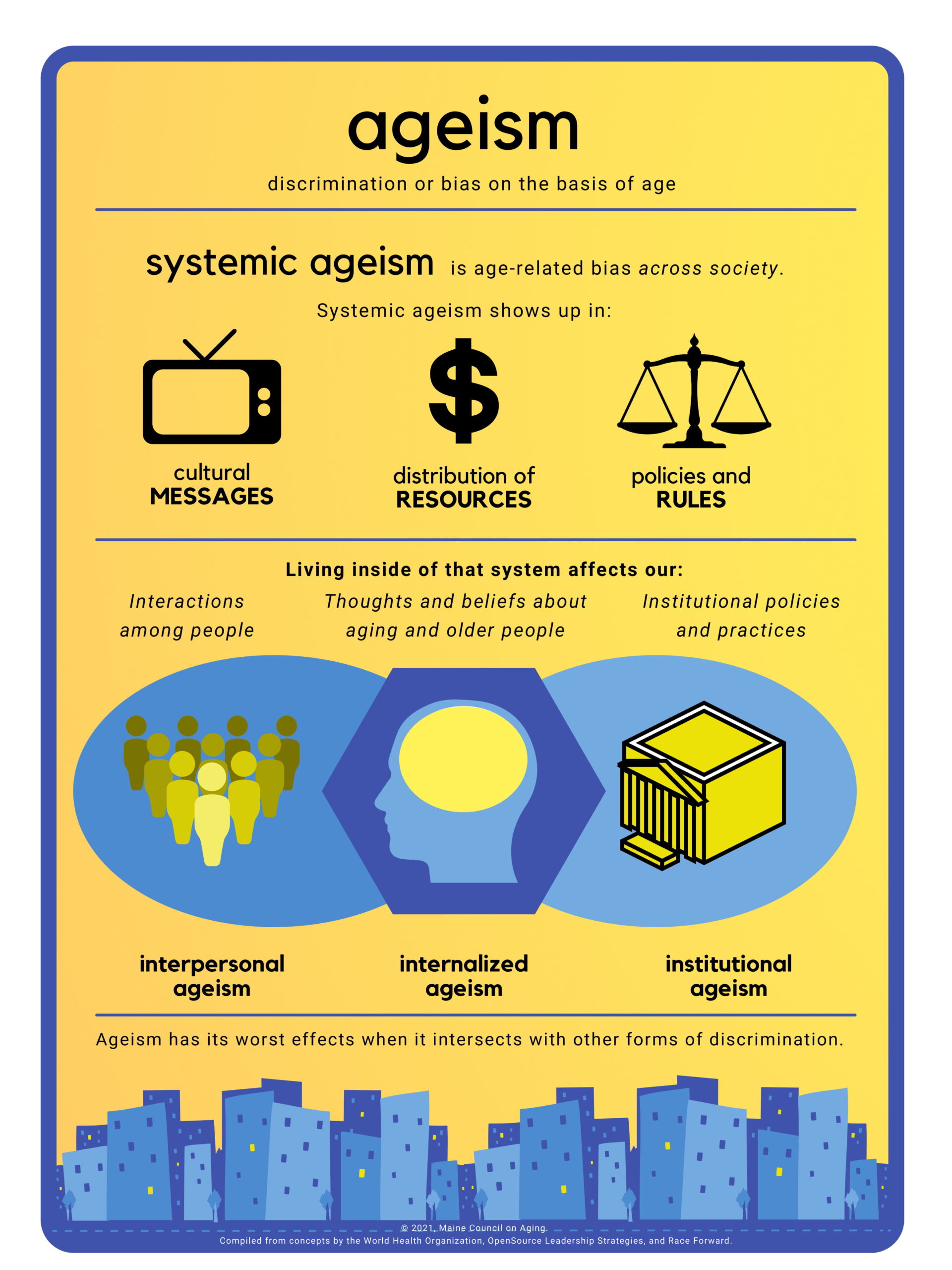

]]> It has been three weeks since my Age Positivity course at the Senior College ended, and it’s time for me to keep my promise that I would report back about the experience. The course progressed from a focus in classes one and two on the negative images of aging we have all internalized and why it is important to replace those ageist messages with age-positive ones, to an emphasis in classes three and four on recognizing and disrupting interpersonal ageism, to an exploration in classes five and six of the ways that ageism is built into institutions, organizations and policies.

It has been three weeks since my Age Positivity course at the Senior College ended, and it’s time for me to keep my promise that I would report back about the experience. The course progressed from a focus in classes one and two on the negative images of aging we have all internalized and why it is important to replace those ageist messages with age-positive ones, to an emphasis in classes three and four on recognizing and disrupting interpersonal ageism, to an exploration in classes five and six of the ways that ageism is built into institutions, organizations and policies.

Classes in this course were spaced two weeks apart to provide us with an opportunity to do some “homework assignments” between classes. As homework between classes three and four, we were assigned to identify, name and disrupt an instance of ageism as we went about our lives. I knew I would have no trouble completing this assignment because I had a doctor’s appointment scheduled between classes three and four, and health-care settings seem to provide particularly fertile ground for the form of ageism that our instructor referred to as “elderspeak.” It turns out that there is a body of scientific research on elderspeak. One review of that research published in 2020 (Shaw C, Gordon J, Williams K. Understanding Elderspeak: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Innovations in Aging. 2020 Dec 16;4451) defines elderspeak as “an inappropriate simplified speech register that sounds like baby talk and is commonly used with older adults, especially in health care settings.” This review of the research went on to note that “Elderspeak is generally perceived as patronizing by older adults and speakers are perceived as less respectful” and that, in patients with dementia, the use of elderspeak on the part of caregivers increases resistance to care. In other words, even when well-intentioned, elderspeak is both insulting and counter-productive.

Sure enough, I didn’t have to wait long to encounter elderspeak at my doctor’s office. After I checked in with the receptionist and was shown to a treatment room, a medical assistant and a student shadowing her came in to update my medical information; and, in the process of asking me her first question, the medical assistant called me “honey.” My assignment was not only to recognize and name interpersonal ageism, but to disrupt it; so, I answered the question and then added, “But I’m one of those activist elders who does not want to be called ‘honey.’” The medical assistant acknowledged my preference and then said, ‘But I’ll probably forget, because I call people that all the time.” The student quickly jumped in to support her, saying, “I do it all the time, too; it’s just a habit.” “Well,” I replied firmly, “It’s a good habit to break.” Afterward, I reflected on how effective my attempt to disrupt this form of ageism had been. First of all, I felt good about having spoken up, especially since I find it easier to advocate for others than to advocate for myself. But I think the medical assistant and the student shadowing her probably attributed my objections to individual quirkiness; I suspect this interaction would have to be repeated many times with many different patients before it had an impact. A better way to reduce the prevalence of elderspeak in health care settings would probably be to explicitly name it as inappropriate in health care education and in workplace policies.

This leads us to the third level of ageism explored in the age positivity course, the institutional level. Institutional ageism includes both official policies and informal practices. For example, most American medical schools have a policy of not requiring any formal instruction in geriatrics for their students, arguing that students learn about geriatrics through interactions with older patients during clinical rotations. This means that what students learn about geriatric practice depends on the behavior being modeled by the health care professionals who supervise them in those clinical rotations. My experience in the doctor’s office, where the medical assistant modeled the use of elderspeak for the student who was shadowing her, shows us how these educational practices can pass along ageism from one generation of practitioners to the next. As a sociologist, I know that institutional discrimination is real, that it is often unintentional, and that it can be especially difficult to disrupt when it is built into informal practices as well as formal policies.

In our final class session, we students were asked what actions we would take to live a more age positive life or to build an age-positive Maine. The responses were as varied and individual as the participants in the class. My own commitment was to once again take up the issue of aging alone and make sure it is included in initiatives to create age positivity. (More about this in a future post.)

]]>People who live with age-positive views and in age-positive cultures live 7.5 years longer than those who don’t, with fewer chronic conditions and less anxiety. People who live with purpose – a reason to get up in the morning – live longer and have fewer cognition problems than those who don’t. Universally, research shows we’re also happiest later in life than at any other time of life.

Yet, our current culture is steeped in negative stereotypes that equate the very act of aging with disease, disability, and death. Popular media pushes us to “fight aging” and too regularly associates age with decline. …

The Project’s primary strategy is to engage audiences from different sectors in direct conversations about age-bias, the impacts of ageism, and the benefits of living and working in an age-positive culture.

Our “conversation” is extending over six class sessions, each 90 minutes long and taking place every other week. When I signed up for it, I wasn’t sure how much I would get out of this course, since I am already well acquainted with the research on the importance of age positivity (and have written about it and taught about it). I needn’t have worried; the class is a delight.

So far, we have had three class sessions. In the first, when we introduced ourselves and explained what had brought us to the course, I was particularly charmed by a classmate in his mid-nineties who said he was in the class because his daughter had signed him up for it, but that he had been reluctant to come because “this is the time of day I usually go to the gym.” Later in this class session, we were asked “What are your thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears about yourself in ten years? Twenty years? Thirty years?,” and I was surprised to realize that, while I could easily imagine myself in ten years, I didn’t seem to have any image of my life past that time. I think this means I need to do some thinking about my fears for those later years, where those fears come from, and what I can do to counter them.

The second class focused on the images of aging that surround us and on how we have internalized and been shaped by those messages. A lively discussion ensued when we were discussing the evidence that those who have internalized negative images of aging live shorter, less healthy lives. One member of the class queried the assumption that being active in old age was better because it resulted in longevity and more years of good health. He said, “Maybe I feel that I just want to sit back and put my feet up and watch TV. I think I’ve earned that right, and if it means that I live fewer years or have more health problems in later life, that’s my choice to make.” Several women in the class immediately jumped in to object that he wasn’t just making that choice for himself but for whomever he assumed would be taking care of him when his health declined.

In the third class, we talked about ageism in interpersonal interactions. The instructor quickly realized that, unlike his classes with younger people, he didn’t need to convince us that such interpersonal ageism exists. The class easily generated many examples, especially of ageism in health care encounters. Our focus in this class session was on how to disrupt interpersonal ageism, and we had fun role-playing such encounters and sharing examples of how we had successfully countered such ageism in our own lives.

I’m already feeling sad that we are halfway through this course. I love the diverse perspectives, positive energy and good will that I’m finding there.

]]>