| CARVIEW |

Sounding Out!

pushing sound studies into the red since 2009- About

- People

- Writers

- Writers A-N

- A-B

- Kemi Adeyemi

- Kaj Ahlsved

- Wanda Alarcon

- Andrew Albin

- Kevin Allred

- Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

- Tim Anderson

- Kevin Archer

- Michael Austin

- Gina Arnold

- Shauna Bahssin

- Kathleen Battles

- Benjamin Bean

- Airek Beauchamp

- Tara Betts

- Colin Black

- Thomas Blake

- China Blue

- Trevor Boffone

- Yvon Bonenfant

- Marcus Boon

- Esther Bourdages

- Bill Bahng Boyer

- Regina N. Bradley

- Mark Brantner

- Alejandra Bronfman

- Cassie J. Brownell

- Justin D Burton

- C

- D-E

- F-G

- Ziad Fahmy

- David Font-Navarrete

- Rob Ford

- Juan Sebastian Ferrada

- Nicole Furlonge

- Milton Garcés

- Luis-Manuel Garcia

- Jennifer Garcon

- Josh Garrett-Davis

- Erik Granly Jensen

- Christina Giacona

- Denise Gill

- Mike Glennon

- Benjamin Gold

- Kariann Goldschmitt

- Travis Gosa

- Carolina Guerrero

- Norie Guthrie and Scott Carlson

- H

- J-K

- L-Mi

- Caleb Lázaro Moreno

- Rebecca Lentjes

- Nati Linares

- Mary Caton Lingold

- Jay Loomis

- Eric Lott

- Bronwen Low

- Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

- Ashley Luthers

- Marit J. MacArthur

- Alexis Deighton MacIntyre

- Owen Marshall

- Carter Mathes

- Tom McEnaney

- Marci McMahon

- Leslie McMurtry

- John Melillo

- Asa Mendelsohn

- Aurelio Meza

- Jeb Middlebrook

- Bonnie Millar

- April Miller

- Lee M. Miller

- Gabriel Salomon Mindel

- Mo-N

- A-B

- Writers O-Z

- O-R

- Michael O’Brien

- Julia Grella O’Connell

- Mandie O’Connell

- Linda O’Keeffe

- Josh Ottum

- Priscilla Peña Ovalle

- Osvaldo Oyola

- Marla Pagán-Mattos

- Andreas Pape

- James Parker

- Leonard J. Paul

- Caroline Pinkston

- Samantha Pinto

- Murray Pomerance

- Scott Poulson-Bryant

- Primus Luta

- Lucreccia Quintanilla

- Iván Ramos

- Anthony W. Rasmussen

- Ian Rawes

- Lilian Radovac

- Marlen Ríos-Hernández

- AO Roberts

- Tara Rodgers

- Christopher Roman

- Pablo Roman-Alcala

- Alexander Russo

- S

- reina alejandra prado saldivar

- Andrew J. Salvati

- Ted Sammons

- Luz María Sánchez

- Michelle Sauer

- Jentery Sayers

- Meg Schedel

- Holger Schulze

- A. Brad Schwartz

- Cam Scott

- Sarah Mayberry Scott

- D. Travers Scott

- Susana Sepulveda

- Christina Sharpe

- Rebecca Shores

- Shayna Silverstein

- Aram Sinnreich

- Phillip Sinitiere

- Jonathan Skinner

- Jacob Smith

- Suzanne E. Smith

- Emmanuelle Sonntag

- Gustavus Stadler

- Justyna Stasiowska

- Jonathan Sterne

- Andy Kelleher Stuhl

- Pavitra Sundar

- Rajna Swaminathan

- Karl Swinehart

- T-Z

- Dustin Tahmahkera

- Ariel Taub

- Toniesha L. Taylor

- Karen Tongson

- Alexander J. Ullman

- Vanessa K. Valdés

- Shawn VanCour

- Neil Verma

- J. Martin Vest

- Salomé Voegelin

- Laura Wagner

- Gayle Wald

- Daniel A. Walzer

- Yun Emily Wang

- Jon M. Wargo

- Eric Weisbard

- Alex Werth

- Kimberly Williams

- Ben Wright

- Nabeel Zuberi

- Christie Zwahlen

- O-R

- Writers A-N

- Guest Editors

- Podcasters

- Frank Bridges

- Leonardo Cardoso

- Brooke Carlson

- Maile Colbert

- David B. Greenberg

- K. A. Laity

- Eric Leonardson

- Sonia Li

- Monteith McCollum

- Andrea Medrado

- Nick Mizer

- Leonard J. Paul

- Craig Shank

- Jennifer Lynn Stoever

- H. Cecilia Suhr

- James Tlsty

- Salomé Voegelin

- Naomi Waltham-Smith

- Daniel A. Walzer

- Cynthia Wang

- Anne Zeitz

- Advisory Board

- Associate Book Review Editor

- Interns

- Writers

- Resources

- Podcast

- Submit

- Home

- CFP Archive

- Call For Pitches for SO!’s Print Volume + Blog: Sonic Presents Due 30 JAN 2023

- EXTENDED!! CFP: Hate and NonHuman Listening, Due 14 July 2025

- EXTENDED through 11/30 CFP: “Racial Bias in Speech AI,” Due 15 Nov 2022

- CFP: The Grain of the Audiobook, Due 7 OCT 2019

- CFP: Mingus Ah Um at 60, Due 5/20/19

- CFP: Soundwalking While POC, Due 12/3/18

- CFP: No Pare, Sigue Sigue: Spanish Rap & Sound Studies, Due 10/1/2018

- CFP: Amplifying Du Bois at 150, Due 5/1/18

- CFP: Gendered Sounds of South Asia, Due 7/15/17

- CFP: Sound in the K-12 School, Due 4/15/2017

- CFP: Sound, Ability, and Emergence, Due 1/15/17

- CFP: Punk Sound, Due 9/15/16

- CFP: Digital Humanities and Listening, Due 4/10/16

- CFP: Medieval Sound, Due 11/15/15

- CFP: Sound and Affect, Due 8/15/15

- CFP: Gendered Voices, 12/15/2014

- 2014-2015 Call for Guest Editors!

- CFP: Round Circle of Resonance: José Esteban Muñoz, 9/15/14

- CFP: Sound and Surveillance, 7/15/14

- CFP: Sound and Pleasure, 4/15/14

- ASA/SCMS Call for SO! Guest Editors Due 11/21

- CFP: Sound and Cities, 11/15/13

- CFP: Sound and Play 7/15

- CFP: Sound and Sports, 4/15/13

- CFP: Sound and Creative Processes, 1/1/13

- CFP: Sound and Pedagogy, 7/1/12

- CFP: Aural Tricks and Sonic Treats, 9/1/11

- by jonstoneb9ece95f42

- in Acoustic Ecology, activism, Article, Book Review, Civic Engagement, Humanism, Language, Listening, Performance, Philosophy, Politics, protest, Public Debate, Rhetoric, Rhetoric/Composition, Silence, SO! Reads, sonification, Sound, Sound Studies, Speech, The Body, Voice

- Leave a comment

SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests (Penn State University Press) is a book “about the sounds made by those seeking change” (5). It situates these sounds within a broader inquiry into rhetoric as sonic event and sonic action—forms of practice that are collective, embodied, and necessarily relational. It also addresses a long-standing question shared by many of us in rhetorical studies: Where did the sound go? And specifically, in a field that had centered at least half of its disciplinary identity around the oral/aural phenomena of speech, why did the study of sound and rhetoric require the rise of sound studies as a distinct field before it could regain traction?

Eckstein confronts this silence with urgency and clarity, offering a compelling case for how sound operates not just as a sensory experience but as a rhetorical force in public life. By analyzing protest environments where sound is both a tactic and a terrain of struggle, Sound Tactics reinvigorates our understanding of rhetoric’s embodied, affective, and spatial dimensions. What’s more, it serves as an important reminder that sound has always played an important role in studies of speech communication.

Rhetoric emerged in the Western tradition as the study and practice of persuasive speech. From Aristotle through his Greek predecessors and Roman successors, theorists recognized that democratic life required not just the ability to speak, but the ability to persuade. They developed taxonomies of effective strategies—structures, tropes, stylistic devices, and techniques—that citizens were expected to master if they hoped to argue convincingly in court, deliberate in the assembly, or perform in ceremonial life.

We’ve inherited this rhetorical tradition, though, as Eckstein notes early in Sound Tactics, in the academy it eventually splintered into two fields: one that continued to study rhetoric as speech, and another that focused on rhetoric as a writing practice. But somewhere along the way, even rhetoricians with a primary interest in speech moved toward textual representation of speech, rather than the embodied, oral/aural, sonic event that make up speech acts (see pgs 49-50).

Sound Tactics corrects this oversight first by broadening what counts as a “speech act”—not only individual enunciations, but also collective, coordinated noise. Eckstein then offers updated terminology and analytical tools for studying a wide range of sonic rhetorics. The book presents three chapter-length case studies that demonstrate these tools in action.

The first examines the digital soundbite or “cut-out” from X González’s protest speech following the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The second focuses on the rhythmic, call-and-response “heckling” by HU Resist during their occupation of a Howard University building in protest of a financial aid scandal. The third analyzes the noisy “Casseroles” retaliatory protests in Québec, where demonstrators banged pots and pans in response to Bill 78’s attempts to curtail public protest.

A full recounting of the book’s case studies isn’t possible here, but they are worth highlighting—not only for the issues Eckstein brings to light, but for how clearly they showcase his analytical tools and methods in action. These methods, in my estimation, are the book’s most significant contribution to rhetorical studies and to scholars more broadly interested in sound analysis.

Eckstein’s analytical focus is on what he calls the “sound tactic,” which is “the sound (adjective) use of sound (noun) in the act of demanding” (2). Soundness in this double sense is both effective and affective at the sensory level. It is rhetoric that both does and is sound work—and soundness can only be so within a particular social context. For Eckstein, soundness is “a holistic assessment of whether an argument is good or good for something” (14). Sound tactics, then, utilize a carefully curated set of rhetorical tools to accomplish specific argumentative ends within a particular social collective or audience capable of phronesis or sound practical judgement (16). Unsound tactics occur when sound ceases to resonate due to social disconnection and breakage within a sonic pathway (see Eckstein’s conclusion, where he analyzes Canadian COVID-19 protests that began with long-haul truck drivers, but lost soundness once it was detached from its original context and co-opted by the far right).

Just as rhetorical studies has benefitted from the influence of sound studies, Eckstein brings rhetorical methods to sound studies. He argues that rhetoric offers a grounding corrective to what he calls “the universalization of technical reason” or “the tendency to focus on the what for so long that we forget to attend to the why” (29). Following Robin James’s The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism, and Biopolitics, he argues that sound studies work can objectify and thus reify sound qua sound, whereas rhetoric’s speaker/audience orientation instead foregrounds sound as crafted composition—shaped by circumstance, structured by power, and animated by human agency. Eckstein finds in sound studies the terminology for such work, drawing together terms such as acousmatics, waveform, immediacy, immersion, and intensity to aid his rhetorical approach. Each name an aspect of the sonic ecology.

Rhetoricians often speak of the “rhetorical situation” or the circumstances that create the opportunity or exigence for rhetorical action and help to define the relationship between rhetor and audience. While the rhetorical action itself is typically concrete and recognizable, the situation itself—which is always in motion—is more difficult to pin down. “Acousmatics” names a similar phenomenon within a sonic landscape. Noise becomes signal as auditors recognize and respond to particular kinds of sound—a process that requires cultural knowledge, attention, and the proverbial ear to hear. A sound’s origins within that situation may be difficult to parse. Acousmastics accounts for sound’s situatedness (or situation-ness) within a diffuse media landscape where listeners discern signal-through-noise, and bring it together causally as a sound body, giving it shape, direction, and purchase. As such a “sound body” has a presence and power that a single auditor may not possess.

Eckstein defines “sound body” as “our imaginative response to auditory cues, painting vivid, often meaningful narratives when the source remains unseen or unknown” (10). And while the sound body is “unbounded,” it “conveys the immediacy, proximity, and urgency typically associated with a physical presence (12). Thus, a sound body (unlike the human bodies it contains) is unseen, but nonetheless contained within rhetorical situations, constitutive of the ways that power, agency, and constraint are distributed within a given rhetorical context. Eckstein’s sound body is thus distinct from recent work exploring the “vocal body” by Dolores Inés Casillas, Sebastian Ferrada, and Sara Hinojos in “The ‘Accent’ on Modern Family: Listening to Vocal Representations of the Latina Body” (2018, 63), though it might be nuanced and extended through engagement with the latter. A focus on the vocal body brings renewed attention to the materialities of the voice—“a person’s speech, such as perceived accent(s), intonation, speaking volume, and word choice” and thus to sonic elements of race, gender, and sexuality. These elements might have been more explicitly addressed and explored in Eckstein’s case studies.

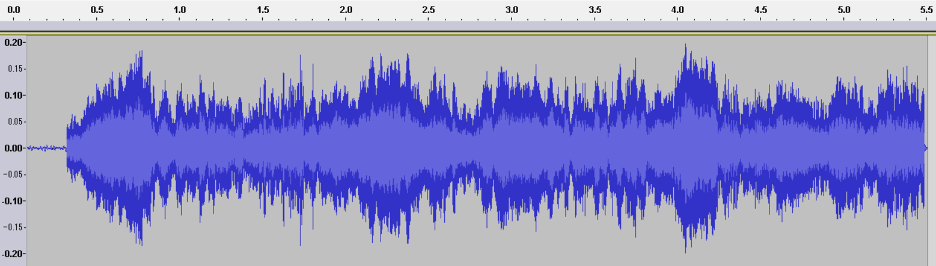

Eckstein uses these terms to help us understand the rhetorical complexities of social movements in our contemporary, digital world—movements that extend beyond the traditional public square into the diverse forms of activism made possible by the digital’s multiplicities. In that framework he offers the “waveform” as a guiding theoretical concept, useful for discerning the sound tactics of social movements. A waveform—the digital, visual representation of a sonic artifact—provides a model for understanding how sound takes shape, circulates, and exerts force. Waveforms also obscure a sound’s originating source and thus act acousmastically.

“[A] waveform is a visual representation of sound that measures vibration along three coordinates: amplitude, frequency, and time” (50). Eckstein draws on the waveform’s “crystallization” of a sonic moment as a metaphor to show sound’s transportability, reproducibility, and flexibility as a media object, and then develops a set of analytical tools for rhetorical analysis that match these coordinates: immediacy, immersion, and intensity. As he describes:

Immediacy involves the relationship between the time of a vibration’s start and end. In any perception of sound, there can be many different sounds starting and stopping, giving the potential for many other points of identification. Immersion encompasses vibration’s capacity to reverberate in space and impart a temporal signature that helps locate someone in an area; think of the difference between an echo in a canyon and the roar of a crowd when you’re in a stadium. Finally, intensity describes the pressure put on a listener to act. Intensity provides the feelings that underwrite the force to compel another to act. Each of these features and the corresponding impact of this experience offer rhetorical intervention potential for social movements. (51)

This toolset is, in my estimation, the book’s most cogent contribution for those working with or interested in sonic rhetorics. Eckstein’s case studies—which elucidate moments of resistance to both broad and incidental social problems—offer clear examples of how these interrelated aspects of the waveform might be brought to bear in the analysis of sound when utilized in both individual and collective acts of social resistance.

To highlight just one example from Eckstein’s three detailed case studies, consider the rhetorical use of immediacy in the chapter titled “The Cut-Out and the Parkland Kid.” The analysis centers on a speech delivered by X González, a survivor of the February 14, 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Speaking at a gun control rally in Ft. Lauderdale six weeks after the tragedy, González employed the “cut-out,” a sound tactic that punctuated their testimony with silence.

Embed from Getty Images.

As the final speaker, González reflected on the students lost that day—students who would no longer know the day-to-day pleasures of friendship, education, and the promise of adulthood. The “cut-out” came directly after these remembrances: an extended silence that unsettled the expectations of a live audience disrupting the immediacy of such an event. As the crowd sat waiting, González remained resolute until finally breaking the silence: “Since the time that I came out here, it has been six minutes and twenty seconds […] The shooter has ceased shooting and will soon abandon his rifle, blend in with the students as they escape, and walk free for an hour before arrest” (69–70).

As Eckstein explains, González “needed a way to express how terrifying it was to hide while not knowing what was happening to their friends during a school shooting” (61). By timing the silence to match the duration of the shooting, the focus shifted from the speech itself to an embodied sense of time—an imaginary waveform of sorts that placed the audience inside the terror through what Eckstein calls “durational immediacy.” In this way, silence operated as a medium of memory, binding audience and victims together through shared exposure to the horrors wrought over a short period of time.

…

Sound Tactics is a must-read for those interested in a better understanding of sound’s rhetorical power—and especially how sonic means aid social movements. In conclusion, I would mention one minor limitation of Eckstein’s approach. As much as I appreciated his acknowledgement of sound’s absence from the Communication side of rhetoric, such a proclamation might have benefited from a more careful accounting of sound-related works in rhetorical studies writ large over the last few decades. Without that fuller context, readers may conclude that rhetorical studies has—with a few exceptions—not been engaged with sound. To be fair, the space and focus of Sound Tactics likely did not permit an extended literature review. There is thus an opportunity here to connect Eckstein’s important intervention with the work of other rhetoricians who have also been advancing sound studies.

I am including here a link to a robust (if incomplete) bibliography of sound-related scholarship that I and several colleagues have been compiling, one that reaches across Communication and Writing disciplines and beyond.

—

Featured Image: Family at the CLASSE (Coalition large de l’ASSÉ ) Demonstration in Montreal, Day 111 in 2012 by Flicker User scottmontreal CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Jonathan W. Stone is Associate Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Utah, where he also serves as Director of First-Year Writing. Stone studies writing and rhetoric as emergent from—and constitutive of—the mythologies that accompany notions of technological advance, with particular attention to sensory experience. His current research examines how the persisting mythos of the American Southwest shapes contemporary and historical efforts related to environmental protection, Indigenous sovereignty, and racial justice, with a focus on how these dynamics are felt, heard, and lived. This work informs a book project in progress, tentatively titled A Sense of Home.

Stone has long been engaged in research that theorizes the rhetorical affordances of sound. He has published on recorded sound’s influence in historical, cultural, and vernacular contexts, including folksongs, popular music, religious podcasts, and radio programs. His open-source, NEH-supported book, Listening to the Lomax Archive, was published in 2021 by the University of Michigan Press and investigates the sonic archive John and Alan Lomax created for the Library of Congress during the Great Depression. Stone is also co-editor, with Steph Ceraso, of the forthcoming collection Sensory Rhetorics: Sensation, Persuasion, and the Politics of Feeling (Penn State U Press), to be published in January 2026.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings –Vanessa Valdés

Quebec’s #casseroles: on participation, percussion and protest–-Jonathan Sterne

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening-–Airek Beauchamp

Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology––Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, and Cloe Gentile Reyes

The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions–Mukesh Kulriya

SO! Reads: Todd Craig’s “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn Harris

Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

But first. . .

An Introduction to Bro-casting Trump: A Year-long SO! Series by Andrew Salvati

“The Manosphere Won.”

That is how Wired succinctly described the results of the 2024 election the day after Americans went to the polls.

Among the several explanations offered for Donald Trump’s stunning victory over Kamala Harris, the magazine’s executive editor Brian Barrett argued, one surely had to acknowledge the crucial role played by that “amorphous assortment of influencers who are mostly young, exclusively male, and increasingly the drivers of the remaining online monoculture.”

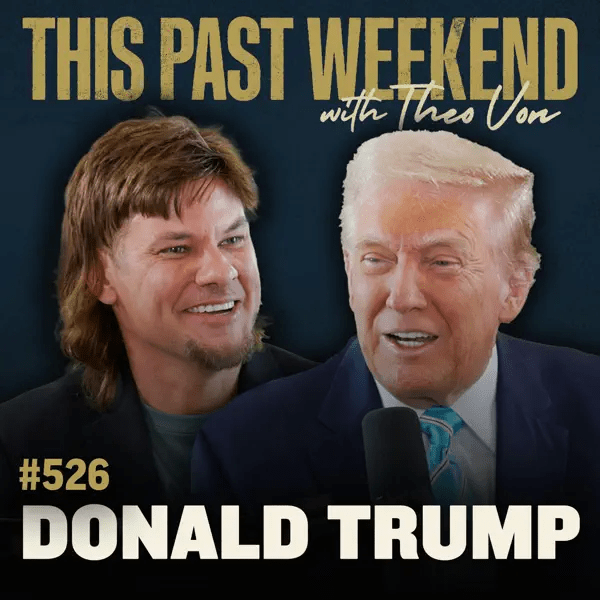

Sure, there might be some validity in saying that Trump’s election had to do with inflation, with immigration policy, or with Joe Biden’s “doomed determination to have one last rodeo.” But his appearance on several popular male-centered podcasts in the months and weeks leading up to November 5 likely did much to mobilize support for his candidacy among their millions of viewers and listeners. Talking to Theo Von, the Nelk Boys, Andrew Schulz, and Shawn Ryan “cement[ed Turmp’s] status as one of them, a sigma, a guy with clout, and the apex of a model of masculinity that prioritizes fame as a virtue unto itself,” Barrett wrote.

Indeed, during the president-elect’s victory speech, given in the early morning hours of the 6th, his longtime friend and ally Dana White, president of the UFC, took to the speaker’s lectern to acknowledge the contributions that these podcasters and their audiences had evidently made in elevating Trump to the presidency for the second time. “I want to thank the Nelk Boys, Adin Ross, Theo Von, Bussin’ with the Boys, and last but not least, the mighty and powerful Joe Rogan,” he said.

As a media strategy, this was something of an evolution of Trump’s approach in 2016, in which the former reality TV star had used Twitter to such great effect to bypass legacy media institutions and bring his unfiltered message directly to voters. This time around, and reportedly at the direction of his 18-year-old son Barron, Trump again leveraged the massive reach of new media platforms to speak directly to his target demographic of Gen-Z men.

But the strategy was also of a piece with Trump’s frequent assaults on the press, which he typically characterizes as the “enemy of the people.” Appearing in some of the friendlier precincts of the podosphere allowed Trump to skirt around mainstream journalists with their “nasty” questions and cumbersome norms of neutrality and objectivity, and to bask in the mutual admiration society that some of these interviews became. Indeed, as Maxwell Modell wrote in The Conversation not long after the election, podcasters, in contrast to professional journalists, “tend to opt for more of a friendly chat than aggressive questioning, using what research calls supportive interactional behavior … this ‘softball’ questioning can result in the host becoming an accomplice to the politicians’ positive self-presentation rather than an interrogator.”

Podcasts, in other words, provided Trump with a congenial space to self-mythologize, to ramble, and whitewash some of his more extreme views.

In total, Trump appeared on fourteen podcasts or video streams during his 2024 campaign (Forbes compiled a full list, including viewership numbers, which can be found here), which together earned a combined 90.9 million views on YouTube and on other video streaming platforms (it should be noted, first, that these are not unique views – there is likely an overlap between audiences; second, that these numbers do not include audio podcast listens, which, because of the decentralized nature of RSS, are notoriously difficult to pin down).

For her part, meanwhile, Kamala Harris also made the rounds on podcasts popular with women and Black listeners – key demographics for her campaign – including Alex Cooper’s Call Her Daddy, former NBA players Matt Barnes and Stephen Jackson’s All the Smoke, and Shannon Sharpe’s Club Shay Shay. It has been suggested, however, that the Harris camp’s failure (or perhaps unwillingness) to secure an appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience was a significant setback, and could have provided an opportunity to reach the young male demographic with whom she was struggling. In any event, while the counterfactual “what-if-she-had-done-the-show” will likely be debated for years to come, Rogan eventually endorsed Trump on November 4, throwing his considerable clout behind the once and future president.

While a comparison between Trump and Harris’s podcast strategy during the 2024 campaign would make for an interesting academic study, in the following series of posts, I will be particularly concerned with Trump’s success with the so-called podcast bros – partially because my own research interests are in the area of mediated masculinities, but also because they may have put him over the edge with a key demographic – with Gen-Z men.

Over the next few posts, I will examine several of Trump’s appearances on largely apolitical “bro” podcasts during the 2024 campaign season, including his interviews with Logan Paul, Theo Von, Shawn Ryan, Andrew Schulz, the Nelk Boys, and Joe Rogan. In the course of this examination, I will pay attention not only to what Trump said on these shows, but also to the way in which they established a sense of intimacy, and how that intimacy worked to underscore Trump’s reputation for authenticity. Along the way, I will also discuss the podcasts and podcasters themselves and attempt to locate them within the broader scope of the manosphere. Finally, given the passage of time since Trump’s appearances, I will consider to what extent, if any, individual hosts have become critical of his administration’s policies and actions – as Joe Rogan famously has.

Before I begin, however, I want to make a quick note about the sources: Following what is quickly becoming standard practice in the field, each of the “podcasts” that I analyze in this series has a video component, and in fact, may very well have been conceived of as a video-first project with audio-only feeds added as a supplement, or afterthought. For this series, though, my interest has centered on podcasting as a listening experience, and so the reader may assume that when I discuss this or that episode of Theo Von’s or Andrew Schulz’s podcast, I am referring specifically to the audio version of their shows. This is also why Trump’s interview with Adin Ross will not appear in this series – it was livestreamed on the video sharing platform Kick, and was subsequently posted to Ross’s YouTube channel (and thus is it technically not a podcast).

With that being said, let’s dig in. I will proceed chronologically, with Trump’s first podcast appearance on the boxer/professional wrestler Logan Paul’s show, Impaulsive, which dropped on June 13, 2024.

****

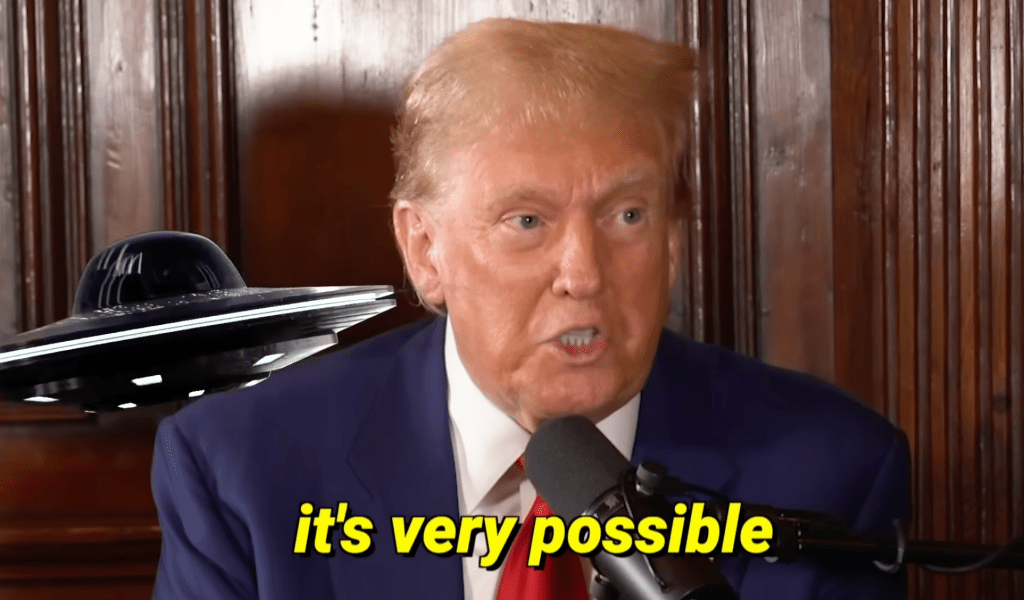

With about 13 minutes remaining in Logan Paul’s roughly hour-long interview with Donald Trump, the conversation turned to aliens. “UFOs, UAPs, the disclosure we’ve seen in Congress recently,” Paul explained, “it’s confusing and it’s upsetting to a lot of Americans, because something’s going, there’s something happening. There are unidentified aerial phenomena in the sky, we don’t know what they are. Do you?”

For his part, Trump responded gamely, and after respectfully listening to Paul, proceeded to tell a story about how, as president, he had spoken with Air Force pilots, “perfect people,” who weren’t “conspiratorial or crazy,” who claim that “they’ve seen things that you wouldn’t believe.” Still, Trump admitted that he had “never been convinced.”

I start with this turn in the conversation not necessarily to dismiss the 29-year-old Paul as a conspiratorial thinker or an unserious interviewer, but rather to highlight the overall tone of the Trump episode, which was overwhelmingly chummy and fawning. It was clear from their deferential posture that Paul and his co-host Mike Majlak were in awe of the former president, and asking such questions was a way of keeping it light and easy.

Logan Paul, after all, is not known for his incisive political commentary. Indeed, in the 17 episodes of Impaulsive that were released in the six months preceding the Trump interview (all of which I have listened to for this piece), political issues hardly featured at all. One exception came during the December 19, 2023 episode with his brother Jake Paul (also a professional boxer, who was recently knocked out in a fight against Anthony Joshua), in which Logan and Majlak discussed the prevalence of right-wing or MAGA content and signifiers as the inevitable backlash to the excesses of the left and the “woke mind disorder,” as Majlak put it. Another example was the January 31, 2024 episode with former co-hosts Mac Gallagher and Spencer Taylor, in which Majlak went on a self-described “rampage” about the problems at the U.S. southern border (in particular, he referenced the Shelby Park standoff, though without naming it), and in which Paul’s father, Greg Paul, got on the mic to declare his support for “Trump 2024.” But other than these incidental moments and superficial takes, the show is not really the place for nuanced discussions of public policy or electoral politics. (Indeed, in the January 31 episode, Paul even attempted to stop Majlak’s rant by noting that listeners didn’t really tune into the show for political discussion).

Nor does Impaulsive, despite all its testosterone-fueled bro-iness, seem to fit comfortably within the manosphere, as I understand that term and what it signifies. Indeed, though Paul and Majlak seem to have fixed ideas about gender and about the differences between men and women, absent from their discussions (at least during the six month sampling of episodes that I listened to) is the kind of misogynistic and reactionary “Red Pill” rhetoric that characterizes manosphere discourses.

This isn’t Andrew Tate, after all, and it’s important that we keep track of the distinction.

Impaulsive, rather, serves as a venue for Paul and Majlak to have informal, free-wheeling conversations with their guests – which have included fellow wrestlers, sports stars, internet personalities, rappers, pastors, and even Chris Hansen – on a range of other topics of interest to the hosts. If there is a throughline in all of this (aside from Paul and Majlak’s interest in how guests navigate their social media presence), it is certainly the relationship between the two co-hosts, their similar immature (we might more charitably say “goofy”) sense of humor, their mutual interest in combat sports, and their past history of online and offline hijinks all providing the basic framework for much of their conversation. It also gives Impaulsive listeners a sense of intimate connection with the pair, a sense that they are in the room as a silent participant in the hang.

And Paul has had a decade’s worth of experience in making comedic content. Having first earned a following by posting short videos on Vine as a college freshman in 2013, he dropped out of school and moved to Los Angeles to pursue a full-time career as a social media content creator. Fortunately for him, the gambit worked, and his content was soon reaching hundreds of thousands of followers across Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in addition to Vine, and a compilation of his videos posted to YouTube amassed more than 4 million viewers in its first week. A number of TV and movie appearances followed, and in 2018, Paul began what would eventually become a professional boxing career with a white-collar match against the British influencer KSI.

Paul’s rise to notoriety wasn’t unmarked by controversy, however. In late December 2017, at a time when he had something like 15 million YouTube subscribers, Paul earned widespread condemnation for his insensitivity after he posted a video to the site showing the body of an apparent suicide victim in Japan’s infamous Aokigahara Forest, and making light of the situation. As a result of the backlash on social media – which included a Change.org petition urging YouTube to deplatform the creator that garnered over 700,000 signatures – Paul removed the video and issued an apology for his actions (this apology was itself criticized for being disingenuous and self-serving, and Paul was later compelled to issue another). For their part, YouTube took disciplinary measures against Paul, which included removing the creator’s channel from the Google Preferred advertising program, and removing him from the YouTube Red series Foursome, among other things.

But that wasn’t all. About a month later, YouTube announced that it would temporarily suspend advertisements on Paul’s channels (the revenue was estimated to be about a million dollars per month) due to a “recent pattern of behavior,” which, in addition to the Aokigahara Forest controversy, now included a tweet in which he claimed that he would swallow one Tide Pod for every retweet he received, and a video in which he tasered a dead rat. The suspension seemed to be little more than a slap on the wrist, however, and two weeks later, in late February of 2018, ads were restored on Paul’s channels.

The controversies continued after the launch of Impaulsive in November 2018. In an episode released the following January, as Paul and Majlak and their guest, Kelvin Peña (aka “Brother Nature”) were discussing their resolutions to have a “sober, vegan January” followed by a “Fatal February” (vodka and steaks), Paul chimed in and suggested that he and Majlak might do a “male only March.” “We’re going to go gay for just one month,” he announced. “For one month, and then swing … and then go back,” Majlak concurred. The implication that being gay was a choice drew sharp criticism online, including a tweet from the LGBTQ+ organization GLAAD, which pointed out, “That’s not how it works @LoganPaul.”

We could continue. But it’s also worth mentioning that in early 2019, Paul underwent a brain scan administered by Dr. Daniel G. Amen, which revealed that a history of repetitive head trauma from playing football in high school had damaged the part of his brain that is responsible for focus, planning, and empathy. Such a revelation may explain some of Paul’s poor decision-making. But it has also been suggested that this may be an excuse for the creator to not own up to his shortcomings. And the diagnosis hardly stopped him from starting a boxing career, which he freely admitted “is a sport that goes hand-to-hand with brain damage.”

But even while Paul’s head injuries may have, to some extent, affected his ability to form human connections, it hasn’t completely severed the possibility. On Impaulisve, Paul often shows a genuine curiosity about his guests, a desire to understand their perspectives, and displays a sense of esteem for those, like the WWE superstars Randy Orton and John Cena, whom he knows personally and professionally outside of the context of the podcast. Even amid the raucous Morning Zoo atmosphere of the show, Paul’s tone when speaking to his guests is usually deferential and flattering, and creates a space not only for sharing intimate revelations about, say, the challenges creators face while living so much of their lives in public (a common topic), but also allows guests an opportunity to present themselves and their work in the best possible light.

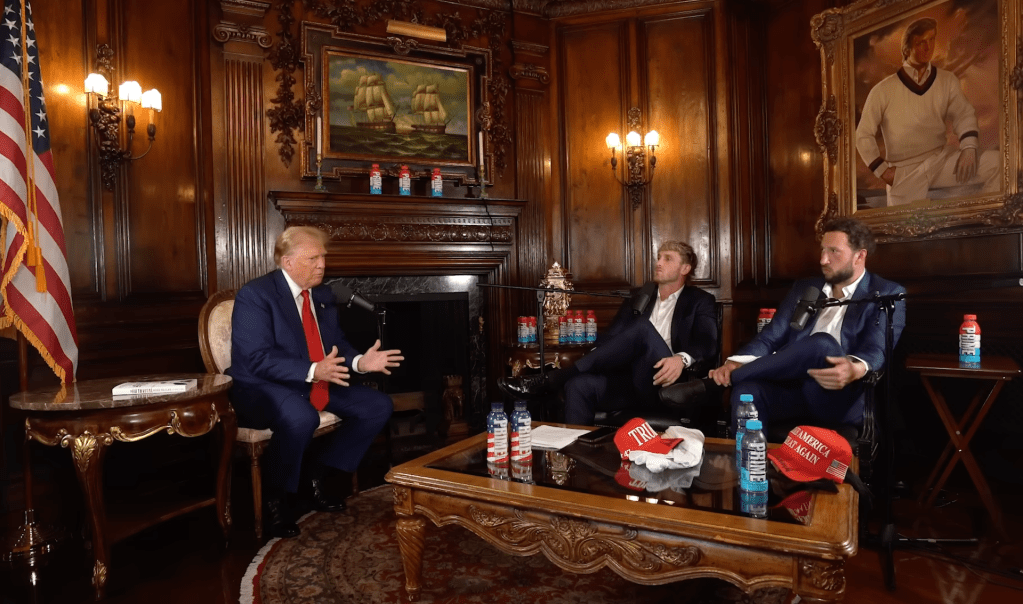

This kind of dynamic was at play during the Donald Trump interview, in which Paul and Majlak offered the former president plenty of opportunities to boast about the historic accomplishments of his first term and of his 2024 campaign, and to air his many grievances – against Joe Biden, the media, the Democratic Party, and the lawyers prosecuting the many cases against him. Impaulsive, in other words, became a platform for Trump to remediate his typical campaign rhetoric, a means of delivering familiar content in a way that privileged quiet intimacy rather than grandstanding performances.

This sense of intimacy derived, in large part, from the setting in which the episode was recorded: Paul and Majlak were sat close to Trump in a wood-paneled room at his Mar-a-Lago estate. But it also stemmed from the kinds of questions that the co-hosts asked Trump. At one point in particular, the conversation turned, as it often does on Impaulsive, to combat sports, and to Trump’s love of the UFC. Opening up on this non-political and heavily masculinized subject – and casually mentioning the cheers he receives when he attends UFC events in person – likely increased the former president’s appeal among Impaulisve listeners, who, according to Paul and Majlak, are mostly wrestling and UFC fans themselves.

Other questions about combat sports – like whether Paul’s brother Jake could win an upcoming fight with Mike Tyson – further cemented the sense that Trump was a fan among fans, and thus created conditions for what podcast researcher Alyn Euritt calls “recognition,” moments in which listeners may feel a sense of intimate connection with a speaker/host and with the larger listening audience.

But what stuck out to me when listening to the episode and thinking about intimacy and podcasting, was the way in which the calm and deliberate pacing of the conversation, with help from the co-host’s gentle guidance, largely prevented the former president from straying into the kind of stream-of-consciousness delivery that characterizes much of his public discourse, and which has come to be known as the Trump “weave.” Kept on course by a friendly interlocutor pitching softball questions, Trump can sound lucid, even rational – and one can see how, in listening to this, his supporters, and even those apolitical listeners in the Impaulsive audience, can get swept up and taken along for the ride.

This is perhaps true for those moments, which occur often, where Trump touts his own successes and popularity. At the beginning of the episode, for instance, after Trump gave Paul a shirt emblazoned with his famous mugshot (which Paul called “gangster” and said “it happened, and might as well monetize it”), the former president launched into a string of familiar complaints about how his prosecution in that case had been an “unfair” miscarriage of justice, and how it had nevertheless resulted in a fundraising boon for his campaign. “I don’t think there’s ever been that much money raised that quickly,” he declared. Uncritically accepted by the co-hosts – and even encouraged by their muffled chortling – such defiant but matter-of-fact posturing may have seemed reasonable to Impaulsive listeners, an understandable response to what was presented as a blatant act of political persecution.

But the apparent honesty and reasonableness of Trump’s views even seemed to extend to his inevitable criticisms of Joe Biden and the American news media, criticisms which were likewise encouraged by Paul and Majlak’s laughter. When Majlak, for instance, asked Trump whether he was “starting to come around or soften your views on some of the networks that you may have not gotten along with in the past?” Trump’s blunt response, “no, they’re fake news,” was met with legitimating chuckles, and with Paul’s concurring statement, “yeah, fake news.” It was Trump’s follow-up, however, in which he put special emphasis on his May 2023 town hall with CNN’s Kaitlan Collins, that he elaborated his position, revealing that though he had thought the network had turned a corner in terms of its friendliness, or at least neutrality, toward him, they were instead “playing hardball.” Delivered almost in a tone of resignation, Trump seemed to give the impression that his poor (in his eyes) treatment by the press was a given, that their hostility, though unfair, was something that simply had to be endured. Again, this explanation, communicated in such an intimate conversational setting, seemed to suggest a cool and reasonable assessment of the situation and prepared listeners to later accept his more extreme view, expressed less than a minute later, that CNN was “the enemy.”

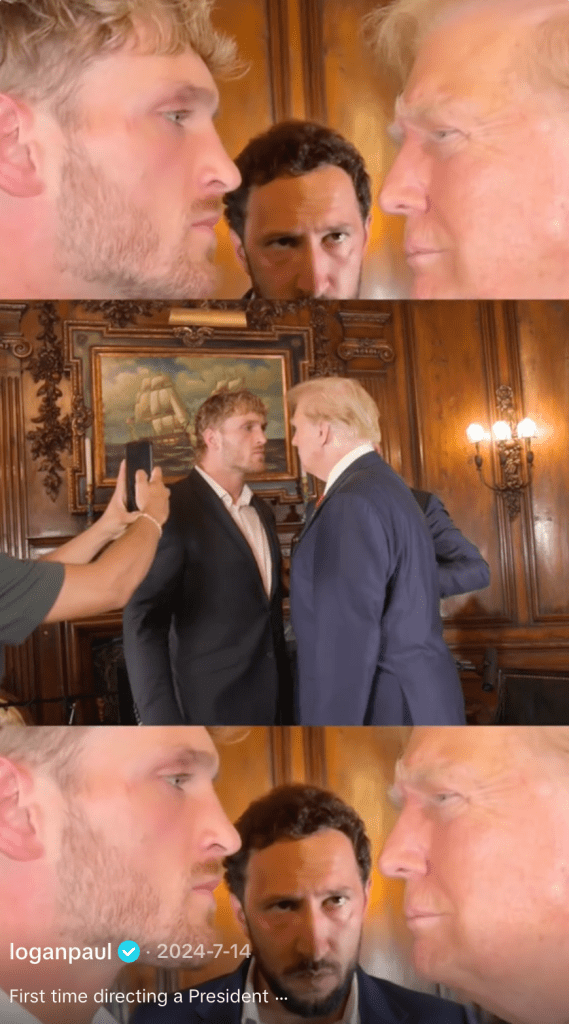

Overall, then, the episode, which ended with Paul, Majlak, and Trump filming a TikTok video in which the podcaster and presidential candidate squared off face-to-face as if shooting a fight promo, offered Trump a platform to connect with other combat sports fans, to burnish his reputation for authenticity, and to legitimize his many grievances. And while the number of new MAGA converts his appearance earned is an open question, what is clear is that Impaulsive afforded Trump an opportunity to directly speak to a demographic that was increasingly important to both campaigns.

—

Series Icon Image Adapted from Flickr User loSonoUnaFotoCamera CC BY-SA 2.0

Featured Image: Paul making his entrance as the WWE United States Champion at WrestleMania XL, CC BY-SA 2.0

—

Andrew J. Salvati is an adjunct professor in the Media and Communications program at Drew University, where he teaches courses on podcasting and television studies. His research interests include media and cultural memory, television history, and mediated masculinity. He is the co-founder and occasional co-host of Inside the Box: The TV History Podcast, and Drew Archives in 10.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Taters Gonna Tate. . .But Do Platforms Have to Platform?: Listening to the Manosphere—Andrew Salvati

Robin Williams and the Shazbot Over the First Podcast–Andrew Salvati

“I am Thinking Of Your Voice”: Gender, Audio Compression, and a Cyberfeminist Theory of Oppression: Robin James

DIY Histories: Podcasting the Past: Andrew Salvati

Listening to MAGA Politics within US/Mexico’s Lucha Libre –Esther Díaz Martín and Rebeca Rivas

Gendered Sonic Violence, from the Waiting Room to the Locker Room–Rebecca Lentjes

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Current Top Posts

Ongoing Series

Latest 5 Forums

Top 5 Forums

RSS Feeds

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

Recent Comments