| CARVIEW |

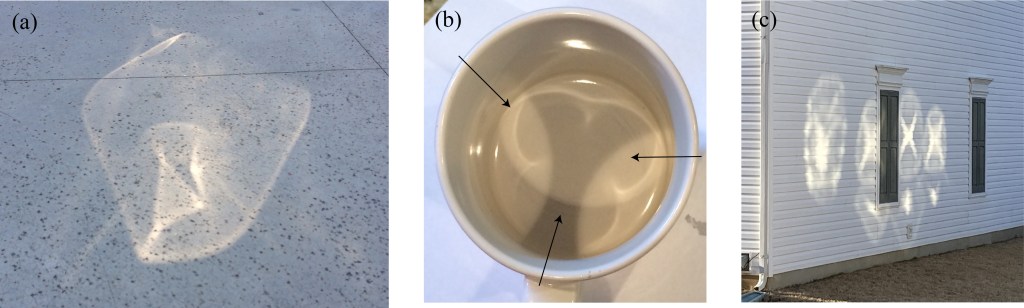

Most of the history of optics concerns itself with designing lenses and mirrors that focus light to a point in order to make image-forming and correcting devices like cameras, eyeglasses, microscopes and telescopes. But light gets naturally focused all the time when it passes through irregularly shaped pieces of glass, reflects off of dented metal surfaces, or goes through water drops. The bright spots of light one gets look much more intricate than a simple spot of light, as a few examples below show.

The first image was a spot of light I saw on the ground at Gaffney Outlet Mall, created by light passing through some sort of decorative glass feature. The second image shows a coffee cup with three bright images inside, one for each light source illuminating the cup (the arrows show the direction the light is traveling). The third image shows spots on the side of a building in my neighborhood, created by light reflecting off of warped windows of a neighboring building.

These images are all very different, but closer inspection shows that they have similar features. They generally consist of a bright area surrounded by an even brighter line. These lines are the caustics. One can see that these bright lines often possess sharp cusp points.

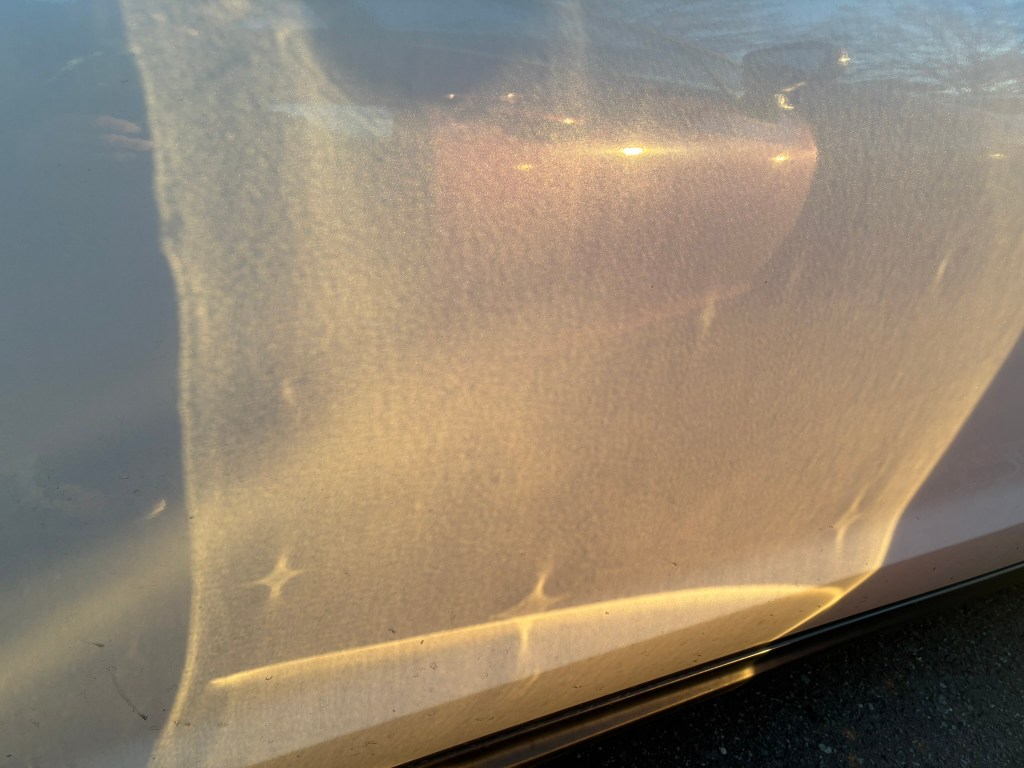

Once you start recognizing these caustic features, you will see them everywhere. The other day I was getting out of my car and my open door reflected the setting sun onto the car next to mine. I had to stop and take a photo of how the small dings and dents in my car created caustic patterns.

But what are caustics, and how do we interpret images like the coffee cup caustic, i.e. what causes them? That’s what this post will be about.

In order to properly talk about caustics, we need to talk a bit about geometrical optics, the oldest picture of optical physics. In geometrical optics, light is viewed as a collection of rays that carry energy traveling along straight line paths through empty space. These rays can change direction when they hit a reflective surface (reflection) and can change direction when they go from one transparent medium to another (refraction). One can imagine that this ray picture came from the classic “god rays” that one can see peeking through clouds and similar phenomena.

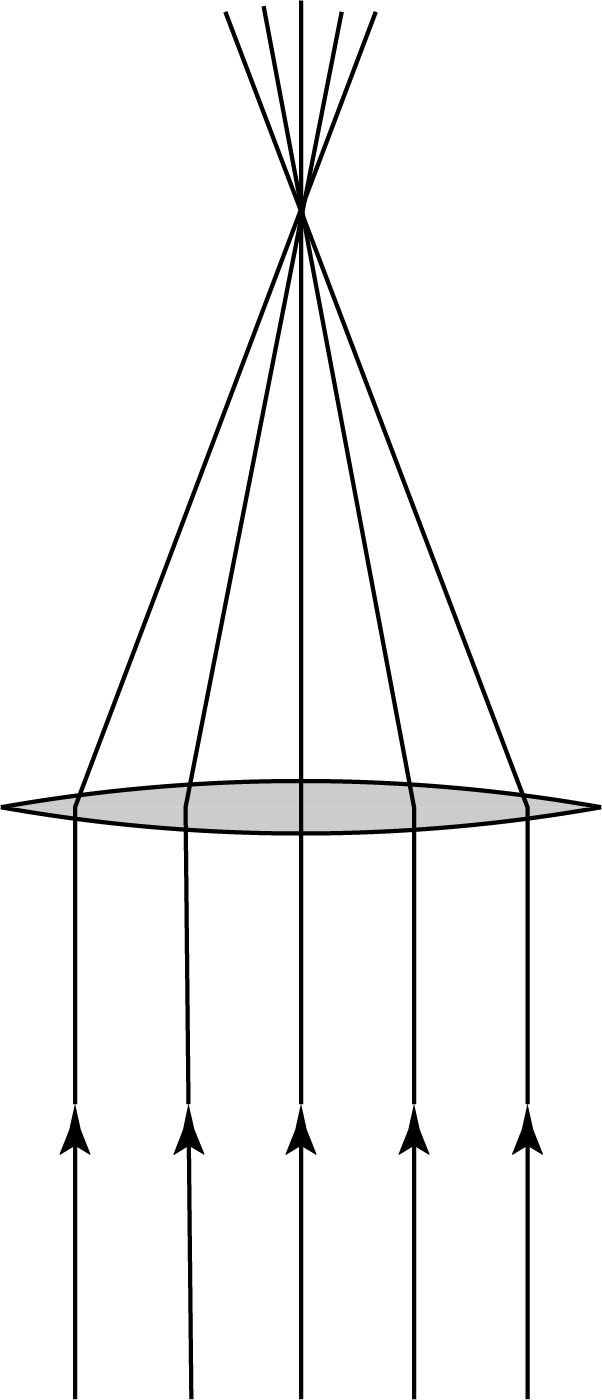

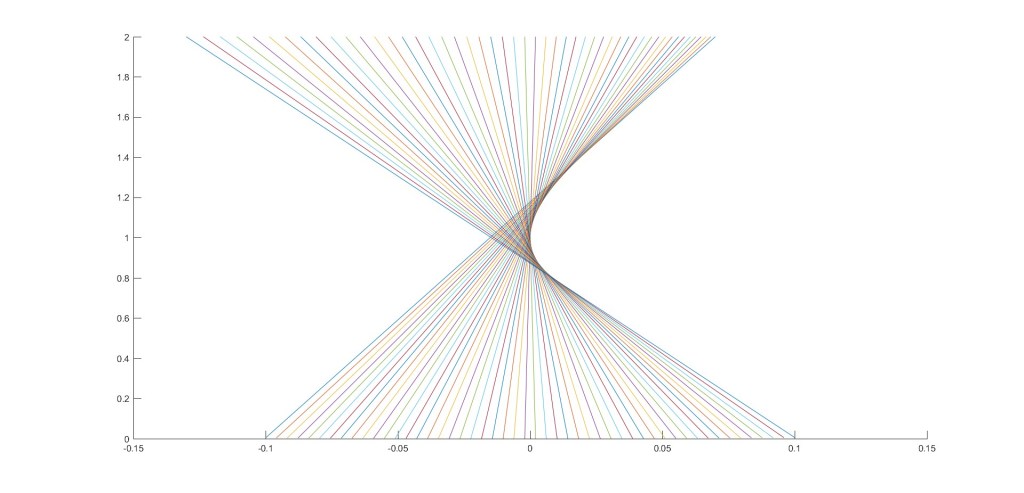

When describing the propagation of light in geometrical optics, we typically draw ray diagrams, showing how the complete family of rays in a beam of light is affected. For example, an ideal lens that focuses light to a point would have a diagram something like the one below.

A very collimated beam of light coming in from the bottom — represented by a collection of parallel rays — is focused to a point on the top. Each ray is bent slightly differently by the lens, which has a spatially varying thickness.

Now what happens if the lens is not ideal? Suppose, for example, our lens is a little thinner on the right and a little thicker on the left. Then you get a picture that looks something like this one:

What is happening here? The rays are all coming from the bottom, as in our lens picture. The rays on the right are being focused at too steep an angle, and they cross the center axis too early. The rays on the left are being focused at too shallow an angle, and they cross the center axis too late. You can see a triangular region where there are two rays that pass through every point — this is the “bright area” associated with caustics that we mentioned earlier.

Most significant, however, is the curved boundary on the right side of the ray picture. One can see visually that the rays appear to have a higher density there than elsewhere; this is the caustic, known as a fold caustic. The reason the rays appear to have a higher density on this caustic curve is because it is a large number of rays nearly on top of each other that are nearly parallel. Mathematically, we say that we have a singularity of ray direction, in which different rays coming from below coalesce into having the same direction at the same position. (If this explanation doesn’t sound great, keep in mind that we’d need to use calculus to really make it precise and clear.) In short, though, our simple image has presented us with a somewhat bright area bounded by a very bright caustic line, as we saw in the first photographs in this post!

You’ve seen fold caustics in one particular phenomenon and never really noticed it! A rainbow is an example of a fold caustic. The bright colors of the rainbow are the result of light reflecting once within a raindrop, and in a previous post I’ve talked about how the rays that contribute the most are those rays that come into the drop nearly parallel and exit the drop nearly parallel on top of each other.

Let’s consider another case of imperfect focusing, in which a lens is a little thinner both on the left and right compared to the ideal lens. Then we get a picture as shown below.

Now the rays on the left and the right of the picture are coming in too steeply and cross the central axis too soon; only the rays near the center come in at an angle where they approach the ideal focal point. The result is an area where three rays pass through, bounded by two bright lines — fold caustics — that come together at a sharp cusped point — the cusp caustic.

It is important to note that the fold and cusp figures are slices through the full three dimensional caustics, that would extend in a third dimension out of the page. The folds become bright surfaces in three-dimensional space, and the cusp becomes a bright line in three-dimensional space.

With this in mind, it should be noted that we wouldn’t be able to observe the cusp if we simply put a horizontal screen in front of the rays in the picture above, because the caustic in this picture is derived as a vertical slice. However, if we tilt the horizontal screen, we would essentially take a different slice through the figure, allowing us to see the folds and cusps clearly.

All of this information allows us to explain the coffee cup caustics we saw earlier. Parallel light rays come into the coffee cup at a downward angle, and reflect off of the circular inner surface of the cup and progress down towards the bottom of the cup, which acts like a screen. Now an ideal lens that focuses light to a point has a parabolic shape; a circular shape is more extreme and will bend the rays at the outskirts at a more extreme angle. The result is a cusp caustic.

These examples may seem like special cases, but in the late 1960s a mathematician named René Thom developed a theory, now known as catastrophe theory, that can be used to show that the folds and cusps are the typical forms of catastrophes. The theory is known as “catastrophe theory” because it can be used to model how systems that are ostensibly continuous can have very sudden changes in their behavior. The proverbial example of such a system is “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” One might expect that slowly adding weight to the camel would cause it to buckle in a continuous way, but this isn’t what one will see — it will remain largely upright until some critical last straw is added, and then it will collapse. If we’re talking about a bridge or a building instead of a camel, this collapse will be quite catastrophic indeed.

We’ll say a bit more about catastrophe theory in a moment, but first let’s talk about what Thom’s theory says about caustics. One can use it to demonstrate that folds and cusps are the primary features one expects to see in natural focusing, so every caustic pattern will consist of folds and cusps. This is why every natural focusing pattern looks at least a little bit the same. The theory also indicates that folds and cusps are the only features that are readily observable in two dimensions, i.e. on a screen, so these are what we typically see.

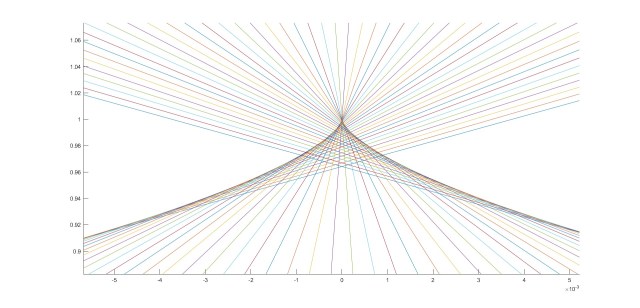

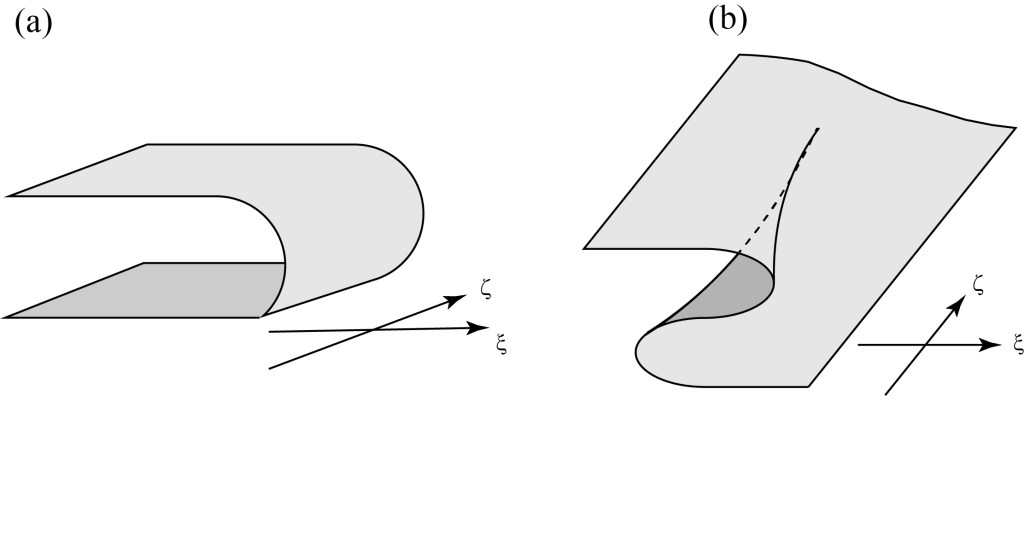

One really neat thing about caustics is that they possess structural stability — that is, if one changes a system parameter, the detailed shape of a caustic may change but it will still maintain its fundamental behavior. A cusp will remain a cusp, a fold will remain a fold. If we squeeze a plastic coffee cup, the curvature of the folds and position of the cusp will change a bit, but they will still be recognizable. This structural stability indicates that these features cannot just disappear but can only be created or destroyed in conserved creation/annihilation events, like electric charges of equal and opposite sign. In particular, we can observe creation and annihilation of cusp features in pairs, as illustrated below.

This figure will require some explanation. Parts (a) and (b) show a cusp caustic in three-dimensional space, which is a surface of two folds coming together. The dark plane represents an observation screen that we put in the path of the caustic. The difference between (a) and (b) is that in the former, the cusp line curves upward, while in the latter the cusp line curves downward.

Now let’s imagine what we see on the screen as we change the height of our observation screen, in particular moving it downwards. Parts (c) and (d) shown the results for the two cases. In (c), we start with two parallel fold caustics bounding a bright region. As the screen moves down, the bright region appears to pinch together as the screen approaches the upward curved cusp line, and then eventually breaks into two observed cusps. For (d), as the screen moves down, the middle of the downward curved cusp line is the last to disappear, and we will see two cusps come together and vanish.

The former case is called a “beak-to-beak” event and the latter is called a “lips” event, for obvious reasons.

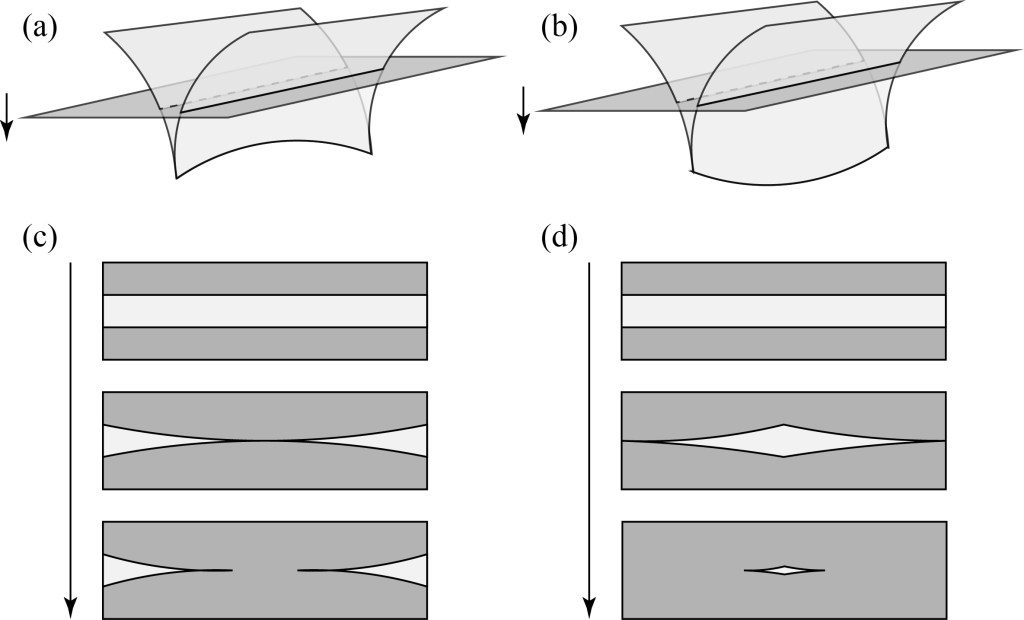

Let’s tie our discussion of caustics back into classic figures of catastrophe theory to see the connection, at least qualitatively. The fold and the cusp catastrophes are usually depicted as surfaces as shown below.

Here, (a) represents the fold catastrophe and (b) represents the cusp catastrophe — you can immediately see from the fold surface why it is called a “fold”: it folds under itself. Let us imagine that the surfaces represent points of equilibrium of some system with respect to the spatial variables . As a visualizer, imagine that the vertical axis represents the position of a particle in some sort of complicated system.

For the fold, there are two equilibrium points for and none for

. For the cusp, there is a cusp-shaped region in the middle where there are three equilibrium points and everywhere else there is one equilibrium point.

The cusp is where “catastrophe theory” really gets its name. Suppose we start on the left on the upper surface and move to the right along it. Eventually, we reach a point where the surface folds under itself. If we continue to increase , the particle will have to drop — suddenly — to the lower surface in order to continue. This is a “catastrophic” jump in the state of the system. As we have said, if this represents something like the equilibrium state of a bridge, this jump could be a big disaster.

Even more curious — suppose that immediately after the drop, we try to correct for it by going back in the negative direction. We do not in fact jump back up to the upper level, but continue left for a time on the lower level until we again run out of surface and jump back to the upper level. This is a phenomenon called hysteresis, in which the behavior of a system lags in response to its inputs, and it is most well-known in changing the magnetization of permanent magnets.

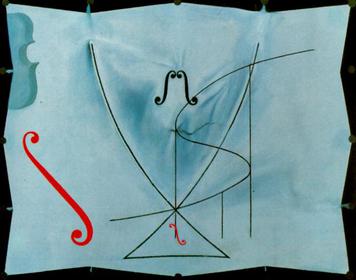

Catastrophe theory became incredibly trendy and popular in the late 1970s, even being the subject of Salvador Dali’s final painting (Dali met Thom in the 70s and became very impressed with his work).

The trendiness of catastrophe theory had it being overapplied and misapplied in fields as far ranging as economics and psychiatry, leading to a scientific backlash by the end of the 1970s. The mathematics is, however, sound, and its use in physics is rigorous and very useful.

How does the cusp catastrophe figure relate to the cusp caustic, besides them both having cusp shapes? We can define a function whose values represent the initial positions of rays entering a caustic region. If we plot that function for a fold, we find that there are two rays on the left of the caustic, and zero on the right — more or less what we found for a fold. If we plot the function for a cusp, we find that there is a cusp-shaped region within which three rays contribute, and only one ray contributes outside of it, which is exactly what we saw for a cusp caustic. It turns out that Thom’s catastrophe theory can be directly applied to characterizing the phenomena of natural focusing. For light rays, however, the only catastrophic thing that happens upon crossing a caustic is a change in the number of rays present.

There are higher-order caustics that can be found, such as the swallowtail and three distinct types of “umbilic” catastrophes. These can only be seen by mapping out their full three-dimensional structure, however, and any projection will look like a collection of folds and cusps.

There are a lot of deep concepts here, and lots of tricky geometry. I had avoided learning about the subject in detail for years because of this, but am happy I have finally figured out enough to understand it. With that in mind, don’t worry if you don’t quite follow all of the arguments here — I will be satisfied if you take away the broad recognition that natural focusing results in common and universal patterns, and start seeing those patterns in your daily life!

]]>To begin, a little background: though there is a long history of invisibility concepts popping up in physics, it was only in 2006 that research in the area exploded with the simultaneous publication of two theoretical papers arguing that it is in principle possible to construct “invisibility cloaks,” objects that will guide light around a center hidden region and send it along its way as if it had encountered nothing at all. I talked about these original papers a looong time ago on this blog; here, let me just show you an illustration from the paper by Pendry, Schurig and Smith that demonstrates the principle.

The lines represent light “rays” traveling around that central region. Remarkably, the first prototype of a cloak demonstrating the basic principle was introduced by Schurig et al. that same year; a photograph of their prototype is shown below.

Their device was designed to work at microwave frequencies, where the wavelength of the waves is about 3 cm. The cloak is constructed from a bunch of small elements known as split ring resonators that, when packed together, can act as an optical material with properties not found in nature. Such materials are now known as metamaterials, “beyond” ordinary materials. We note that this device is flat, and was designed to cloak against microwaves propagating through the region between two parallel metal plates. It was a far cry from the ideal theoretical cloak, but demonstrated that the cloaking principles are sound.

The problem with the original 2006 cloaks is that their “perfection” requires material properties that are extremely difficult to produce in a laboratory, especially for visible light wavelengths, which are less than a micron. In particular, the cloaks require anisotropic materials, i.e. materials whose optical response depends on the polarization of light and the direction the light is traveling, as well as magnetic materials that possess a response to the magnetic field of the illuminating light as well as the electric field. Materials that satisfy the conditions to create a “perfect” cloak do not exist in nature and nobody is really sure how to make them in practice, at least at a size that would be useful.

To get around this, researchers have designed modified invisibility devices that trade perfection for simplicity. The microwave cloak mentioned above used simplified material parameters in its design; the result was a cloak that guided waves around the central region but still scattered and reflected some of the waves incident upon it. The implicit reasoning seems to be: making a device that is 90% invisible with current technology is much more efficient than trying to develop new and uncertain technology to get to 100%. (After all, as I have said in talks, the predator from the movie Predator was overall quite visible, but managed to wipe out Arnold Schwarzenegger’s entire special forces unit!)

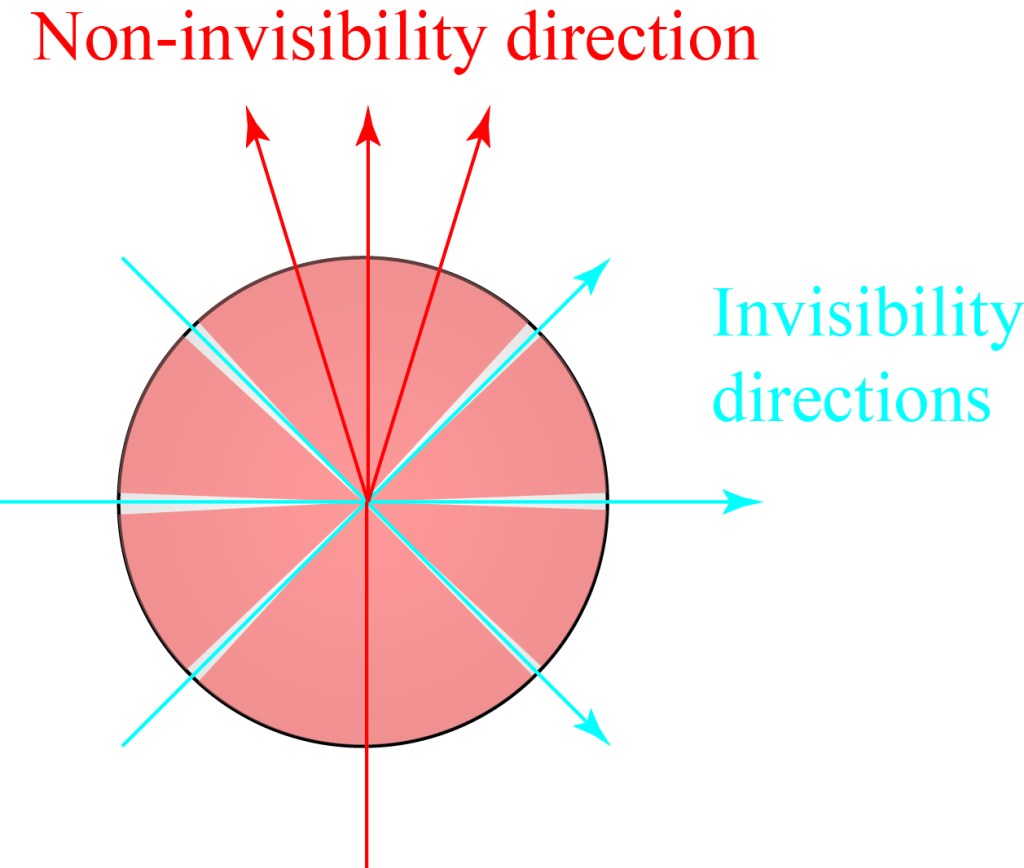

My own PhD research was on pre-2006 invisibility physics, and so I have a lot of knowledge of the history of the subject. Before 2006, theoreticians had shown that perfect invisibility is impossible for ordinary materials, i.e. materials that are isotropic and non-magnetic. But in 1978, Anthony Devaney published a theoretical paper1 showing that it is possible to make objects that are invisible for any finite number of directions of illumination from ordinary materials — and he presented a mathematical method to design such objects.

The basic principle is illustrated — crudely — below, for an imagined object that is designed to be invisible from three specific directions. If we illuminate from any of those three directions, the light passes through the object and carries on as if it had encountered nothing. If we illuminate from any other direction — passing through the red regions — the light will be scattered and the object detectable.

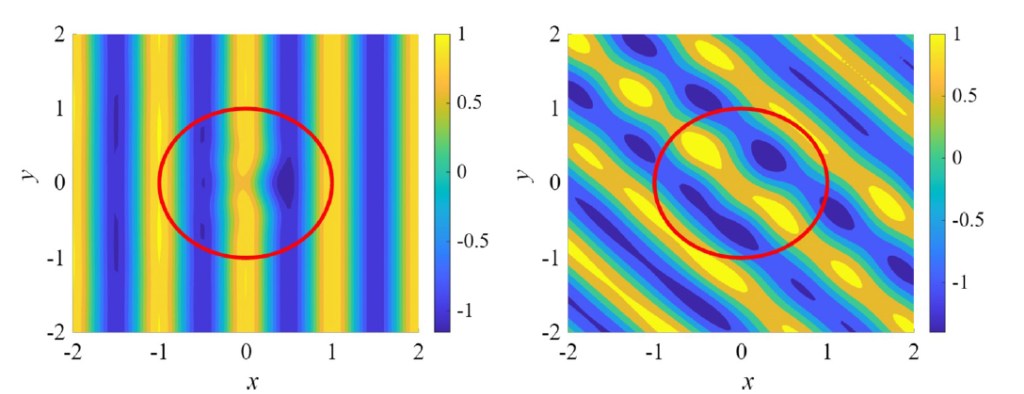

A simulation of light hitting from an invisibility direction and a non-invisibility direction, taken from our paper, is shown below. In the left image, a wave is illuminating the object from the left, and one can see that it passes through the object (outlined with a red circle) with no distortion. The field is distorted within the object, but when it leaves it is as if it never encountered it in the first place. In the right image, a wave comes in at an angle from a non-invisibility direction, and it is significantly distorted all around the object.

A natural question comes up from Devaney’s work, however: what happens if we construct objects that are invisible for an increasing number of directions? In principle, we can construct an object that is invisible for any number of directions, so we could construct an object invisible from 1000 directions, or a million. There seem to be two possible outcomes: 1. As we increase the number of invisibility directions, the object overall becomes increasingly invisible. 2. As we increase the number of invisibility directions, the light scattering between those directions (the red regions in my illustration from before) increases dramatically, keeping the object largely visible.

Ray performed simulations looking at how much the overall scattering of one of Devaney’s objects changes as the number of invisibility directions increases. It should be noted that each of these objects is different, so their overall optical properties were normalized to make sure the same amount of optical “stuff” is present for each object. We constructed two sets of objects using Devaney’s method and looked at the trend as the number of directions increases from N = 1 to N = 6. The objects, like the experimental microwave cloak described earlier, were taken to be two-dimensional to simplify the calculations.

We found that the objects in fact do become overall more invisible as the number of directions is increased! We only needed to consider a small number of invisibility directions because the drop in total scattered power is quite dramatic, dropping orders of magnitude by N = 6. Evidently, even though objects of this sort can never be “perfectly” invisible, they can become arbitrarily close to perfect.

This is a fascinating observation, but doesn’t solve all of our invisibility problems. The material properties of the object are still quite complicated, and Devaney’s method naturally introduces optical gain into the objects, a phenomenon that is hard to implement and control experimentally. It was fascinating to see these properties emerge, as Devaney himself never actually constructed any examples of his objects, he just showed that in principle they could be constructed!

Our research shows that there are still interesting aspects of invisibility to explore, and more approaches available beyond the famous “cloaking” approach of 2006!

******************************************************8

- A. J. Devaney; Nonuniqueness in the inverse scattering problem. J. Math. Phys. 1 July 1978; 19 (7): 1526–1531.

For those unfamiliar, Sigma Xi is the Scientific Research Honor Society founded in 1886. The society performs a lot of outreach to the public and supports scientific research in general, and I was happy to be nominated to be a member a few years ago.

The Distinguished Lecturer Program selects a number of lecturers every year who can be invited to speak at Sigma Xi Chapters, and I offered to talk about two of my classic broad appeal topics — falling cats and invisibility — as well as one I’ve been working on for a while: the history of conservation of energy in physics.

So if you know any Sigma Xi Chapters looking for cool lectures, send them my way!

]]>I seem to be on a bit of a haunted house kick lately, as the last book I blogged for 2025, A Haunting on the Hill, and the book I’ll blog about today, Twelve Nights at Rotter House (2019) by J.W. Ocker, are both very classic setup haunted house books! In fact, I bought them both on the same bookstore trip.

Twelve Nights at Rotter House, however, is distinct in the sense that the narrator of the book has deliberately opted to make his stay in a haunted house as much like a classic haunted house book!

Felix Allsey is a travel writer whose specialty is books on creepy destinations. He has achieved a small amount of success but his career hasn’t really taken off like he’d hoped he would, so he aims for his next project to be the ultimate real-life haunted house story! He chooses the 19th century Rotterdam Mansion, known as Rotter House, as his topic, an edifice that legend holds has had as many horrible deaths within it as rooms. He arranges an extended stay within the mansion with its current owner, and plans to keep himself isolated in the house, with no contact with the outside world, for 13 days straight. He won’t even set foot outside. He won’t have a phone to use, and the house has no electricity, so it will be him, a bag of snacks, and a few pieces of portable electronics to get by.

Felix’s plan is to deliberately provoke as many haunted house tropes as he possibly can during his stay, and he can’t do it alone. He invites his oldest friend Thomas, a believer in the supernatural, to join him, even though they had a falling out a year earlier and hadn’t really spoken since.

At first, their stay is completely mundane, punctuated more by disagreements than supernatural phenomena. But then unexplained events start to pile up and escalate, and it begins to feel like the house is building towards something. What was originally going to be a book about staying in a supposedly haunted house transitions into documenting the haunting itself. But even though both men know that there is no historically documented harm from a ghost, they start to wonder if they might be the first…

Twelve Nights at Rotter House is a fun, fast-paced book, with chapters divided into the twelve days stayed at the house. (You will note that Felix’s plan was to stay 13 days, so you get some foreshadowing right from the beginning.) The house and its history is fun and macabre, with each bedroom labeled by Felix using the alleged type of death that happened within it. The history of the titular builder of the house is also given in imaginative detail, as is a piece of memorabilia from that builder that Felix brings along to spur the spirits.

The biggest charm of the book, however, is its meta discussion of horror fiction and its tropes. Felix and Thomas are both horror afficionados, and their discussions of both fictional and real life horror stories and their implications for their own predicament is a constant enjoyment. Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and the original movie version, The Haunting, both get a positive mention.

One thing I’m not sure about is how satisfying I found the finale of the novel, though it is always a challenge to find a good conclusion to a haunted house. It is extremely well done and well written, I just haven’t decided if I personally enjoyed it! But the rest of the novel more than makes up for any thoughts I have on the subject.

Overall, I found Twelve Nights at Rotter House to be a great haunted house story that carried me along at a brisk pace and was exactly the right amount of fun I want from a book of this type!

]]>One of my favorite horror movies of all time is Robert Wise’s 1963 The Haunting, a brilliant adaptation of one of my favorite horror novels of all time, Shirley Jackson’s 1959 The Haunting of Hill House. When I happened to come across Elizabeth Hand’s 2023 novel A Haunting on the Hill, there was really no doubt about picking it up to read.

For those who might be unfamiliar, The Haunting of Hill House is the story of a team of four investigators who arrive at the infamous Hill House with the goal of uncovering proof of the supernatural. But Hill House is an entity in and of itself, and a malevolent one, and it subtly and then not-so-subtly manipulates the temporary residents until it finds one that it can break and destroy. The novel is a classic haunted house tale, but also a magnificently horrific tale of psychological manipulation and abuse. In every haunted house story, the house itself is the main character, but that has perhaps never felt more true than in Shirley Jackson’s novel.

Hand’s A Haunting on the Hill is a follow-up to the original novel, set in the present day, authorized and even solicited by the Jackson estate. We again follow a group of four people who opt to reside in the house for a short period of time, but this time it is a group of artists who have chosen the house as a location to workshop a stage play. We have Holly, the playwright, who stumbles across Hill House during a trip and decides to spend a small art grant to rent it. We have Nisa, Holly’s girlfriend and a singer, who will provide the music and singing for the play. We have Stevie, a former addict and actor who will play one of the two major roles, and we have Amanda, an aging actress who views this role as her chance to claim some small amount of stardom again.

Each of the quartet has their own desperate motivations for wanting the play to work, keeping them in the house well after common sense has told them they should leave. And each of them has their own skeletons in the closet that the house can prey upon. And even if they decide to leave, a severe winter storm that is rapidly approaching may take the choice away from them…

To me, the novel works in part like the inverse of a murder mystery. From Jackson’s original novel and the history of the house as given, we expect that it will attempt to claim one of the visitors as its own — we spend most of the novel wondering who will be the first one to break. In the original The Haunting of Hill House, it is quite clear who is going to be targeted by the supernatural presence, but here it could be any of them, which is a big part of the fun. We get to watch the house probe each person for weaknesses, one by one, until it finds the perfect target.

Hill House is generally a subtle haunting (unlike the awful 1999 adaptation of the story), and there is a slow buildup of unusual events, glimpses of strange beings, and inexplicably lost time before the finale. Hand does a remarkable job of keeping the tension high and the ghosts just out of sight throughout. She brings back some of the classic phenomenon of Jackson’s original tale but adds her own twists along the way — Hill House has learned many tricks since people visited it in the 1959 novel.

Overall, A Haunting on the Hill is a wonderful continuation of the story of Hill House, and I enjoyed it immensely. I finished the last 75 pages of this 300 page book in one reading, as one events started spiraling out of control I wanted to find out what would happen!

The book includes an afterward by the author explaining part of the process of writing the book and includes one small surprise that delighted me and I will not spoil here!

(As a final note: since I’ve mentioned every other adaptation of the original novel, I should note that the 2018 Mike Flanagan television series The Haunting of Hill House is also excellent, though a very loose adaptation.)

]]>Light has wave properties, and as a wave it can do wavy things like other types of waves — including swirling around a central point like a vortex. When a beam of light manifests one or more of these swirling regions, it is typically referred to as a “vortex beam” and the individual swirling structures are known as “optical vortices” (naturally). Beams possessing optical vortices turn out to be really useful in a lot of applications, and the field of study of such beams, and related “singular” beams, has become known as “singular optics.”

A vortex is a localized, conserved, and discrete structure in a wavefield and when we think of vortex beams, we usually think of beams possessing a finite number of vortices. An infinite number of anything is a concept alien to physics in general, as “infinity” is generally considered an unattainable idealized limit.

I’ve been obsessed with infinity in the context of optical vortices, however, and have published some really neat results on this subject (I will elaborate momentarily). Thus when I came across a 2021 paper by Kovalev and Kotlyar1 titled “Optical vortex beams with the infinite topological charge,” I was immediately intrigued! In this blog post I will give an overview of what optical vortices are, how they behave, and why it is fascinating that one can apparently cram an infinite number of vortices in a beam of light!

Our starting point is to discuss some basic features of waves, and then see how optical vortices naturally arise from this description; I will draw a lot from my old, more extensive, post on singular optics.

What do you imagine when you think of a wave? Many people, including physicists, probably imagine something like the following image.

This wavy line might represent a snapshot in time of waves on a string, if you were to repeatedly wave the left end end up and down. The ripples travel along the string to the right (hence the black arrow), maintaining their shape. The ripples repeat, and we can therefore characterize the current state of the wave at a particular position and time by an angle from 0 to 360 that we call the phase of the wave, as illustrated below.

This is a picture of a wave on a one-dimensional string. What do waves in three dimensions, like light waves, look like? To visualize them, we imagine only drawing the parts of the wave where it is at its maximum value, i.e. 0/360 degrees. These will tend to be surfaces in three dimensional space, and we call them the wavefronts of the wave. The simplest theoretical picture of such a wave is called a plane wave, because the wavefronts are parallel planes; the wave itself propagates, and carries energy, perpendicular to the planes.

But it is also possible for wavefronts to be twisted together, like the levels of a parking deck! A simple example of this is shown below.

This represents a wave traveling upward, and the wavefronts effectively circulate around the central axis as time passes, like a spinning drill bit. This sort of structure is what we refer to as an optical vortex.

It is a bit impractical to study optical vortices by drawing three-dimensional pictures. When we detect light waves, we almost always measure the intensity (and indirectly the phase) by measuring it on a planar detector that measures the cross-sectional behavior of the beam. For the simplest optical vortex, the phase would then appear something like below.

In the cross section, the phase increases from 0 to 360, colored black to white, as one travels counterclockwise around the central point, which happens to be a zero of intensity. The phase is singular at that point, since we cannot define the phase if the wave amplitude/intensity is zero — if there is no wave waving, we can’t evaluate the phase!

We say these simple optical vortices are typical, or generic, features of wavefields, because any time we interfere three or more waves together, we expect optical vortices to appear. Here’s a simulated intensity and phase for four randomly-oriented plane waves:

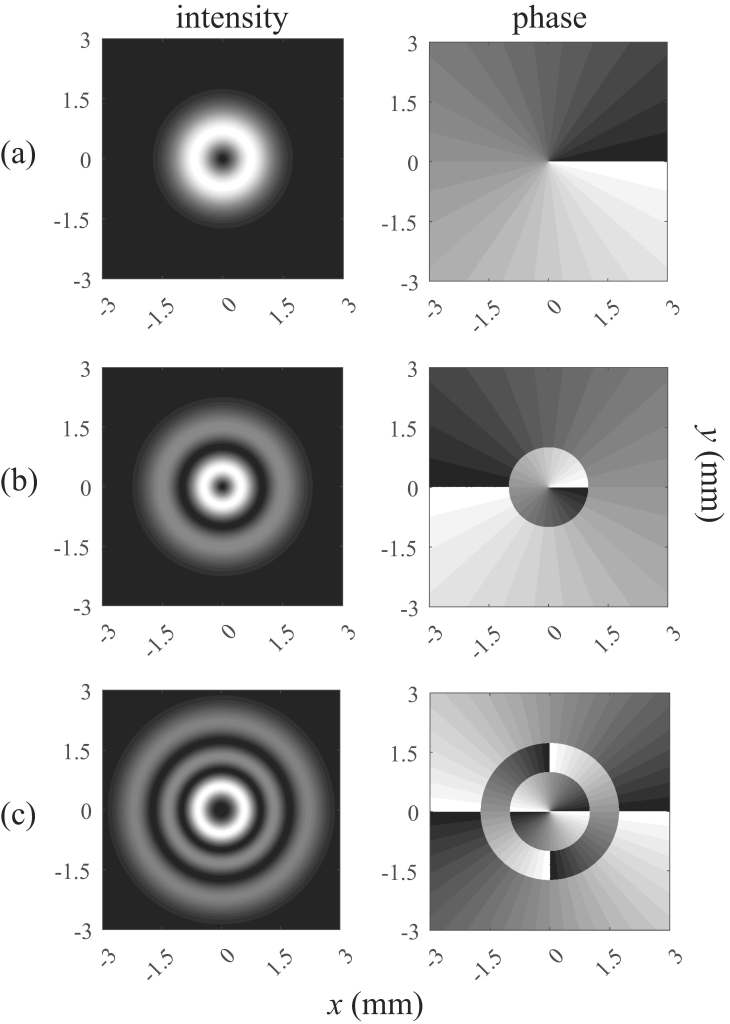

The singularities are easy to spot in the phase — they’re to locations where all shades of gray come together. One can see that for some of them, the phase increases by 360 when one makes a counterclockwise circle around them, and for others the phase decreases by 360. These are the typical vortices that can appear, but it is possible to make beams that possess central vortices where the phase twists more rapidly; one class of such beams are known as the Laguerre-Gauss beams, and the intensity and phase of a selection of them are shown below.

In the topmost one, the phase increases by 360 as one goes counterclockwise around the center; in the second, the phase decreases by 360 along a similar path. In the third, the phase increases by 720 degrees — it is a second-order vortex. It turns out that we can have a vortex of any integer order: +1, -1, +2, -2, +3, -3, and so on. The order represents the number of 360 degree changes the phase goes through as one circles the vortex, and every vortex has an integer order, which we also call the topological charge.

Why is it called a “charge”? It turns out that a vortex charge, like electrical charge, is a conserved quantity, and in general cannot spontaneously appear or disappear without annihilating with an equal and opposite charge. This property of stability — combined with the aforementioned discreteness of topological charge — make vortices attractive as information carriers in optical systems. A lot of work has been done, including by me, to study what happens to vortices when you propagate them long distances through the atmosphere.

Vortex beams have another property that makes them particular useful and interesting — because of the “twist” in the phase, they carry orbital angular momentum, and they can impart that angular momentum on objects they illuminate. This property has been used in optical micromanipulation to trap and rotate microscopic particles.

One natural question that follows from the aforementioned discussion: if topological charge is conserved, and appears in equal and opposite amounts, how can we get vortex beams, which have a net nonzero topological charge? This question was first asked2 by Professor Sir Michael Berry in 2004, and he looked theoretically at one of the original ways of generating a vortex beam: passing an ordinary Gaussian beam through a so-called spiral phase plate, as illustrated below.

Imagine that this ramp-like structure is made of transparent glass, and light shines through it from below. The light will be delayed passing through the glass, and this delay will cause the phase to twist around the center of the spiral. If the thickness if the spiral is chosen correctly, the phase will come out with a twist that is some multiple of 360 degrees — we will have created a vortex beam!

Berry asked: what happens if we don’t have a perfect phase plate, but one that effectively imparts a fractional twist on the phase between 0 and 360 degrees? The answer is that, at every half-integer value of the effective topological charge, i.e. 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, etc., an infinite number of singularities appear, stretching off into the darkness of the beam. A picture of what this looks like near the beam center is shown below.

An infinite number of plus-minus pairs are created, and as the fractional plate is increased beyond a half-integer, we get a remarkable Hilbert Hotel-style annihilation of charges, where each charge annihilates with it opposite neighbor, leaving one extra charge in its place! Berry didn’t comment on the relation to Hilbert’s Hotel back in 2004, so in 2016 I wrote a paper highlighting this remarkable connection3.

The violation of topological charge conservation is allowed to occur because, once an infinite number of pairs are present, the topological charge is undefined, just as the following sum is undefined.

Depending on how we sum this infinite series, we can make it take on any value we want! For example, if we put parenthesis around the first pair and every pair that follows, we have

.

But if we start the parenthesis at the second term, we have

.

The conservation of topological charge can be violated because topological charge cannot be evaluated when there are an infinite number of plus-minus charges in the field!

This Hilbert’s Hotel mechanism has been demonstrated experimentally several times, including by a collaboration I was a part of4.

So it is possible to have an infinite number of positive and negative charges appear in a beam to make the total undefined, but can one actually make the topological charge itself infinite? Surprisingly, the answer appears to be “yes!” Kovalev and Kotlyar drew inspiration from a paper by Abramochkin and Volostnikov that was first published way back in 19935. In that earlier paper, the authors showed method to theoretically impart a finite number of vortices on a beam that would remain shape invariant on propagation, i.e. as the beam travels, it will retain its shape and its vortices.

Kovalev and Kotlyar noticed that there is no reason why that Abramochkin and Volostnikov method can’t be used to construct a beam with an infinite number of vortices, with an infinite topological charge!

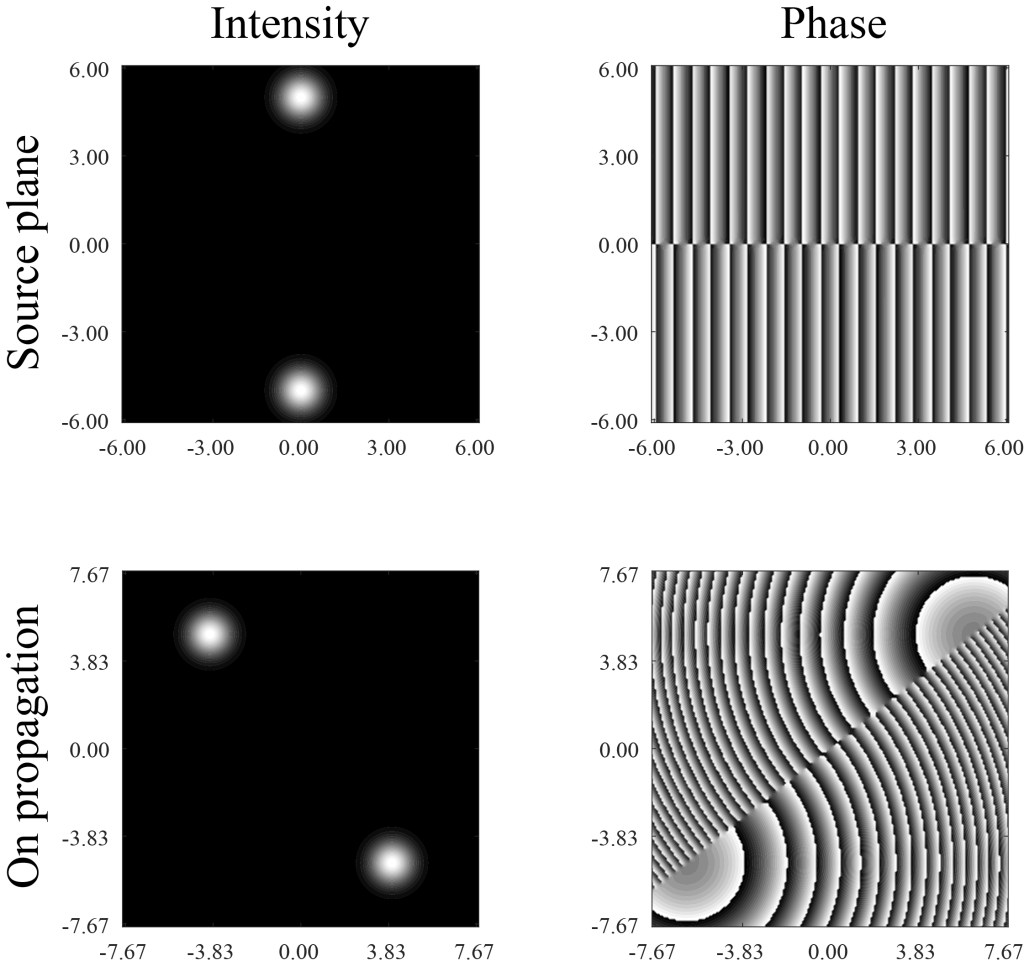

I won’t go into all the math here — this post is complicated enough already! — but we can show some examples. Below is a simulation of a beam with an infinite number of positive vortices, shown both in the source plane and after propagation for 50 meters. The line of vortices basically splits the beam into two bright spots, with the line running between them.

Obviously, we can’t see all the singularities, which stretch off in a line towards infinity, and are effectively lost in the darkness at the beam’s edge. On propagation, the entire beam rotates, eventually rotating a full 90 degrees as it approaches infinity.

What happens to the orbital angular momentum of the beam? Though there is an infinite topological charge, and in principle infinite phase circulation, most of it happens far away in the low intensity rim of the beam, and Kovalev and Kotlyar were able to show that the total orbital angular momentum is consequently finite.

An in principle infinite number of zeros in a beam is not completely unprecedented, because researchers have long known about so-called nondiffracting, or Bessel, beams, which have a Bessel function transverse profile. The intensity of such a beam is a series of rings of decreasing brightness with zero rings between them.

Those zero rings, however, do not possess a topological charge, and so are not as seemingly paradoxical as the infinite topological charge beams described here.

One question that isn’t completely answered by Kovalev and Kotlyar is a method for constructing a beam with infinite topological charge. They note that a beam with an infinite number of zero lines — like a Bessel beam, but vertical instead of circles — can be converted with lenses into an infinite topological charge beam, but that beam with an infinite number of zero lines itself can only be approximately constructed by ordinary means. It is to be an interesting open question as to whether some sort of simple beam, like a Laguerre-Gauss beam, can be converted optically into one of these unusual vortex beams. (Though I think I just figured out how to do it.)

Overall, the paper by Kovalev and Kotlyar again demonstrates that the concept of infinity can play a role in physics problems in truly surprising and enlightening ways!

***************************************************

- A.A. Kovalev and V.V. Kotlyar, “Optical vortex beams with the infinite topological charge,” J. Opt. 23 (2021), 055601.

- M.V. Berry, “Optical vortices evolving from helicoidal integer and fractional phase steps,” J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 6 (2004), 259.

- G. Gbur, “Fractional vortex Hilbert’s Hotel,” Optica 3 (2016), 222-225.

- E. Abramochkin, V. Volostnikov, “Spiral-type beams,” Opt. Commun. 102 (1993), 336-350.

This book I was only able to find available through Amazon.

Back in October, a friend tipped me off at the last minute to the 2025 Charlotte Bookpalooza, a fun party and opportunity for local authors to share and sell their books. I immediately dashed out the door (literally last minute) to the event, and opted to pick up a few titles.

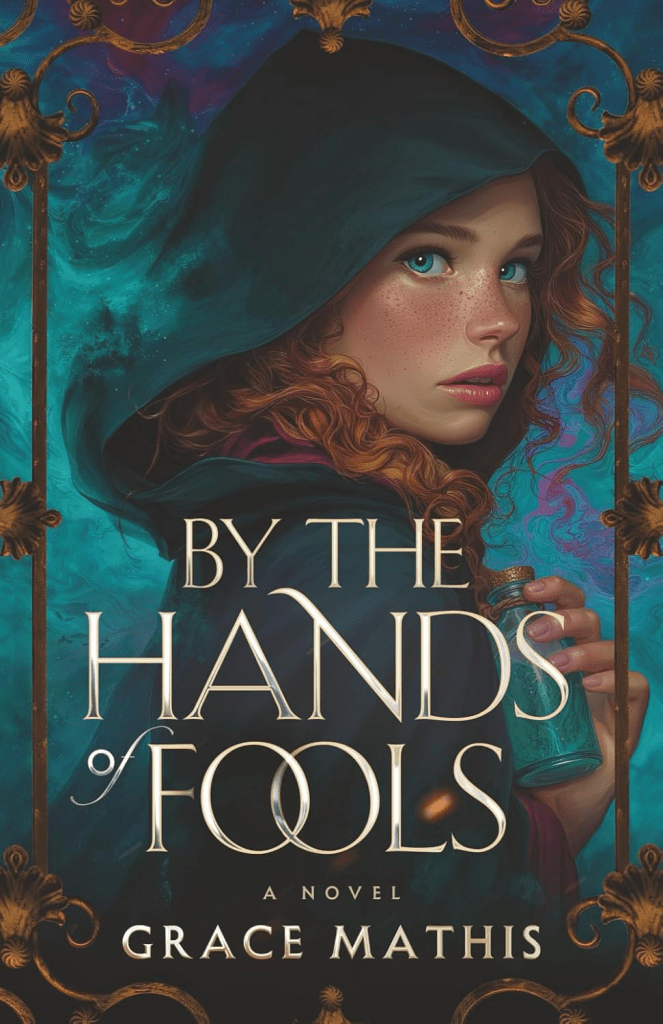

Most of the books were in genres that I don’t usually read, but that’s okay! This was an opportunity for me to support local authors and also step outside of my usual reading conventions, though I still went for books that feature something strange or unusual. The first one I opted to read is By the Hands of Fools (2025), by Grace Mathis.

By the Hands of Fools is a young adult fantasy romance — like I said, not exactly my usual thing, but the premise intrigued me enough to give it a read, and I enjoyed it immensely. It is also a “caper” story, featuring a gang of rogues attempting to pull off a seemingly impossible job.

The book begins by introducing us to Kyra Clearkeep, an apothecary and secret purveyor of poisons as she sneaks into the king’s prison to talk to her incarcerated brother Korin. Kyra has recently lost access to her supplier of raw materials, and Korin is the only one who can provide her information on an alternate source. But their conversation is interrupted by the arrival of other unauthorized personnel: members of The Fools, an infamous gang of rogues, thieves and criminals. The Fools capture Kyra and take her to their leader, Flynn, who demands her help. They need her special skills to accomplish their most dangerous job yet: breaking into the royal palace before the coronation of the new king to overthrow him. The rationale? The previous King Reeve supposedly died of natural causes, by Flynn knows he was murdered by Thorne, the man who plans to usurp the throne. Kyra isn’t given much choice in the matter, though she is promised the freedom of her brother if she agrees to help.

Time is of the essence, and The Fools will have to infiltrate the palace during the coronation ball, when it is swarming with guards on high alert. But there are many factors at play, and the best laid plans never go well…

By the Hands of Fools is a surprisingly long novel — some 460 pages — but it is also fast-paced. The chapters roughly alternate between the perspectives of Kyra and Flynn, and the individual chapters tend to be only a few pages long. This makes the book somewhat ideal as a read-a-couple-of-quick-chapters-before-bed book, but also meant it took me longer to finish because I always ended up reading less than I usually do when reading a book with fewer stopping points! Kyra and Flynn have their own secrets and perspectives on the events as they unfold, and it is fun to see their different reactions to events.

The book jumps into the action pretty much immediately and rarely stops, the momentum carrying it through to the end. There are enough twists and turns along the way to keep the reader entertained, and a wide variety of characters — primarily the different Fools with their different specialties — to make things unpredictable.

This is Mathis’ first book, and I would say it is an excellent first outing! I personally feel like the story could’ve been tightened up a little bit here and there, but it is a small quibble with a tale that I enjoyed a lot.

Mathis has clearly put a lot of thought into her fantasy world, and the book includes a map of the Kingdom of Kaltoa where the adventure is set and its system of magic — yes, magic ends up playing a pivotal role — is well-laid out.

Overall, I enjoyed By the Hands of Fools a lot, and look forward to seeing what else Mathis has in store for us in her writing in the future!

]]>It’s been a while since I really indulged in this, largely due to a struggle in finding good book covers. Also, my inspiration comes and goes, but I’ve been in the mood to mess around again, so here we go…

One of those political jokes that was most amusing in the moment, but this one has lasted so long I’m guessing that people still get the reference!

Another one that feels forever relevant these days!

This next one had a blurb that was so perfect for the topic that I just left it as is!

I’m always happy when I think of an idea for a cover that doesn’t involve politics! Pulp crime novels work well for this.

There is an entire subgenre of books that have covers featuring angry cats, and I am here for it.

Then we get right back into the current events crapola…

I don’t know what has happened to the NYT lately, but they deserve a lot of mockery. Here I just borrow the title of one of their pieces. On the plus side, this cover had been sitting in my folder lacking inspiration for literally years before this.

This next one was a “strike while the iron is hot” current event joke, and if you don’t get the reference now, consider yourself blessed.

And we wrap up with one more political fake cover!

That’s all for now! Hopefully I’ll continue to be inspired and you’ll see more covers from me soon!

]]>Another post from the archives while I work on new stuff!

]]>Sharing another classic history of science post from the archives! This one is about the rather heated history of the illusion known as Pepper’s Ghost.

]]>