| CARVIEW |

How can they both be right? I think they are operating at different levels. Yes, individual agents make their particular planning decisions. In aggregate, these decisions drive monetary variables like interest rates, exchange rates, liquidity demand, etc. However, these variables then feed back into the next round of planning decisions. Moreover, at least some of these plans take into account the effect of the agent’s actions on the monetary variables. So you get classic chaotic/complex behavior with temporarily stable attractors, perturbations, and establishing new regimes. There may even be aspects of synchronized chaos. I think the monetary variables are the key emergent phenomena here. They are like “meta prices” that provide a shared signal across just about every modern economic endeavor.

Food for thought. I’m going to keep this in mind when processing future articles on the economy and see if it helps my thinking.

]]>If you’ve listened to this the whole way through (which you should), I’m curious as to how it will affect your habits, if at all. And why?

]]>

In just the past few months, a growing number of cities have taken to ticketing and sometimes handcuffing teenagers found on the streets during school hours.

In Los Angeles, the fine for truancy is $250; in Dallas, it can be as much as $500 — crushing amounts for people living near the poverty level. According to the Los Angeles Bus Riders Union, an advocacy group, 12,000 students were ticketed for truancy in 2008.

Why does the Bus Riders Union care? Because it estimates that 80 percent of the “truants,” especially those who are black or Latino, are merely late for school, thanks to the way that over-filled buses whiz by them without stopping. I met people in Los Angeles who told me they keep their children home if there’s the slightest chance of their being late. It’s an ingenious anti-truancy policy that discourages parents from sending their youngsters to school.

The column was based on a report by the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, which finds that the number of ordinances passed and tickets issued for crimes related to poverty has grown since 2006.

Hey, no one likes poverty, right? Let’s pass a law!

]]>Thus, I was not surprised to read this article (hat tip to Tyler Cowen at Marginal Revolution) on modern farming by an honest to goodness family farmer. It is full of good examples of the tradeoffs I suspected were lurking. For instance, by using herbicides, farmers reduce the need to till, which is a major source of soil erosion. Hog crates and turkey cages may seem inhumane, but they prevent sows from killing piglets and turkeys dying from drowning. Crop rotations that decrease the need for synthetic fertilizer increase the amount of water needed to produce the desired crop.

Read the whole thing. It reinforced my confidence in the general rule of trying to avoid legislating solutions. Send pricing signals by allocating resource rights and taxing negative externalities. Then let the market do its optimization.

]]>[The incident] is an extraordinary example of what happens when you get… a dozen people with an average IQ of 160… working in a field in which they collectively have 250 years of experience… employing a ton of leverage.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of a [government-led] rescues of a private [corporation]. If a [company], however large was too big to fail, then what large [company] would ever be allowed to collapse? The government risked becoming the margin of safety. No serious consequences had come about in the end from the… near-meltdown.

Was the incident:

a) The savings and loan scandal

b) The collapse of Enron

c) The sub-prime mortgage meltdown

d) none of the above

First correct answer gets to invest in an exciting new bridge project I’m involved with in New York!

]]>While I agree that misplaced incentives were a fundamental problem, the question of how to change this is rather more deep and complex than I think many people realize.

Our economy is, of course, an evolutionary system. Successful businesses grow in size and their practices are imitated by others; unsuccessful businesses vanish. This process has led to many good business practices, even in the financial sector.

However, evolution does not always yield the best outcomes, in biology or in economics. Our recent crisis illustrates two key limitations of evolutionary systems, limitations which allow bad ideas to evolve over good ones.

The first problem has to do with time lags. Suppose Financial Company A comes up with an idea that will yield huge sums of money for five years and then drive the company to bankruptcy. They implement the idea, obfuscating the downside, and soon the company is rolling in cash. Investors line up to give them money, magazines laud them, and other companies begin imitating them.

Not so Company B. Company B believes in long-term thinking, and can see this idea for the sham it is. They persue a quiet, sound strategy, even when their investors begin pulling money out to invest in A.

We would like to think that in the end, Company B will be left standing and reap them benefits of their foresight. But there is a fundamental problem of time-scales here: by the time A folds, B may already be out of business, due to lack of interest from investors. In theoretical terms, there is a fundamental problem when the evolutionary process proceeds faster than the unfolding of negative consequences. In these situations, good ideas never have a chance to be rewarded, evolutionarily speaking.

One might argue that investors, not to mention government regulators and ratings agencies, should have forseen the flaw in A’s plan. But this highlights a second limitation of the evolutionary process: it favors complexity. Simple bad ideas can be detected by intelligent agents, but complex ones have a chance to really stick. If Company A’s idea was so complicated that no one aside from a few physicists could figure it out, investors and regulators could easily be fooled.

It’s not clear to me how to patch these flaws in the evolutionary system. Increased transparency and oversight will help, but unless we can somehow cap the complexity of financial instruments (difficult) or slow down the evolutionary process (impossible), I’m not sure how we’ll avoid similar crashes in the future.

]]>First up is a provocative post by the ever-interesting Scott Sumner. Rafe in particular should read it because Sumner starts from one of Rafe’s favorite premisse that “laws” of nature are purely cognitive constructs. We should measure them by their usefulness and not ascribe to them any independent existence. So Newton’s laws of motion are useful in certain contexts. Einstein’s are useful in others. But neither are ground truth. Moreover, we will never find ground truth. Just successively more accurate models.

Sumner uses this bit of philosophy to justify abolishing inflation, not, “…the phenomenon of inflation, but rather the concept of inflation.” More specifically, price inflation. He explains why this concept is ill-defined and not only unnecessary, but confusing, for understanding the macroeconomy. He asserts that we should expunge it from our models. It doesn’t really exist anyway, so if models do better without it, we won’t miss it in the least.

]]>RafeFurst: I strongly support a soda tax! RT @mobilediner: check it out: a Soda Tax? https://amplify.com/u/dvl

coelhobruno: @RafeFurst what about diet soda? Would it be exempt?

RafeFurst: @coelhobruno no diet soda would not b exempt from tax. Tax should be inversely proportional to total nutritional content. Spinach = no tax

Lauren Baldwin: I do as well … and while they are at it they should tax fake fruit juice too.

Kevin Dick: I think this would be an interesting experiment. I predict a tax does not cause any measurable decrease in BMI.

Kim Scheinberg: New York has had this under consideration for a year. Perhaps surprisingly, I’m against it. In theory, people will drink less soda. In reality, it will just be another tax on people who can afford it the least.

Leaving aside the “rights” issues and just focusing on effectiveness, I guess we can look towards cigarette taxes and gasoline taxes and see what the lessons are. What do these forebears suggest?

As an FYI, there is supposedly a new total nutritional score (zero to 100) that is to be mandated on all food in the U.S. by the FDA. Can anyone corroborate this and its current status? Presumably this would be the number to base a tax on.

]]>

The District, New York and Los Angeles are on track for fewer killings this year than in any other year in at least four decades. Boston, San Francisco, Minneapolis and other cities are also seeing notable reductions in homicides.

Full article is here, in which more sensible police approaches are given credit for the decline.

While it’s probably true that police deserve a lot of credit, it helps to remember that violence is a virus and it spreads from person to person. The more violence people see around them, the more violence that breeds. And the converse is also true. The exogenous factors are hard to suss out, but my suspicion is that the general rise in wealth and well-being in the world is the main factor. This is consistent with the counterintuitive but real fact that violence has been in decline for centuries and we currently live in the most peaceful time ever.

Kevin points out:

I often mention the availability bias when quoting statistics on crime. If you ask people, they’ll say crime has gotten worse–IMO because media has become consistently better at shoving stories of violence into our brains. But the statistics say otherwise.

This is especially poignant when you talk about child abduction by strangers. People think this is a much worse problem (and why you don’t see kids playing in their neighborhoods). But I believe the statistics show the incidence is not any different than it was when we were growing up.

Which brings us to the role of media in propagating myths and creating self-fulfilling prophecies.

I’m curious, what are the statistics on abductions and predatory crime towards children now versus 30 years ago?

]]>Shadows live in a simple world. They glide effortlessly across any sort of surface, oblivious to the higher dimension of space in which 3-D bodies move, collide and sometimes block the paths of rays of light.

Shadows have no idea how important that third dimension is, and how objects in it endow those very shadows with their quasi-physical existence. Indeed, the laws of shadow physics all depend on the third dimension’s presence. And just as the clueless inhabitants of the shadow world require an extra dimension to explain how they exist and interact, reality for humans may also depend on an invisible dimension or dimensions unknown.

This analogy by Tom Siegfried is the single best didactic tool I have encountered to explain the concept that there are (likely) many dimensions to the universe beyond the three (plus time) that we experience as humans.

His article just so happens to be about the unification of the supercold and the superhot (sort of like saying “nothing” and “everything” are really the same thing), and the experiment which may be the first to validate string theory’s real-world predictive power.

]]>What’s really great about it, in addition to the message itself, is that it uses visual language to make its point. I love what Cellucidate is doing (check out the video on their home page). If more cancer biologists used a system like this to validate and communicate ideas, we’d be a lot farther along in understanding and treating cancer effectively (see my previous post).

]]>One preface I think will help is to understand that genome, karyotype and chromosome refer roughly to the same thing. Here are several schematics that I will present without explanation that together illustrate how genes relate to genome/karyotype/chromosome structure, and how that in turn relates to the so-called genetic network (loosely equivalent to the “proteome”). Of course “gene” is an outdated and inaccurate concept, so don’t get too hung up looking for genes here, just understand that they are sub-structural elements of the genome.

From MSU website

From eapbiofield.wikispaces.com

From Heng’s paper titled”The genome-centric concept: resynthesis of evolutionary theory”

Now onto the paper. I’ll point out that I’ve eliminated the scholarly references in the original text simply for clarity, but I don’t want readers to think that the authors have not properly credited the research that goes into the statements/claims made below. If you’d like to read the original paper, email Henry Heng whose address is on the abstract above. Also note that all emphasis in the quotes below is mine.

Somatic Evolution

…cancer progression is an evolutionary process where genome system replacement (rather than a common pathway) is the driving force.

It has become clear that a correct theoretical framework for cancer research is now urgently needed and the concept of somatic evolution represents just such a framework.

The increased NCCA frequencies reflect increased survival advantage while increased CCAs reflect a growth advantage. [NCCAs and CCAs are chromosomal aberrations, like gene mutations but at the genome level]

This last quote is reminiscent of the RNA autocatalysis experiments reported on earlier this year which showed divergent evolution towards two co-existing phenotypes, one that more quickly gobbled up available resources and another that was more efficient at using resources to reproduce quicker. Perhaps there is a basic principle at work in both systems (autocatalytic RNA populations and somatic cell populations).

Instability / Heterogeneity / Diversity

Clearly, as there is no defined cancer genome (the vast majority of cancer cases display different karyotypes representing different genome systems), there is no defined cancer epigenome either.

…the most common feature in tumors is a high level of genome variation…

Understanding the importance of heterogeneity is the key to understanding the general evolutionary mechanism of cancer.

…the true challenge is to understand the system behavior (stability or instability)…

When closely examining the contribution of various genetic factors, it is clear that many of the genetic loci or events are only significantly linked to tumorigenicity when they contribute to system instability (which is closely linked to genome level heterogeneity).

…it is relatively easy to establish a causative relationship between system heterogeneity and cancer evolution, as heterogeneity is the necessary pre-condition needed for cancer evolution to occur….

…instability imparts heterogeneity, which is acted on by natural selection.

The predictability of cancer can be accomplished by measuring the system heterogeneity that is shared by most patients rather than characterize each of the individual factors that contributes to cancer.

Virtual Stability / Chaotic Synchronization

Heterogeneity provides a greater chance of success that a system can adapt to the environment and survive.

…heterogeneity ‘‘noise’’ represents a key feature of bio-systems providing needed complexity and robustness.

…epigentic alteration is an initial response when the genome system is under stress.

It turns out, lower levels of ‘‘randomness’’ are essential for higher levels of regulation when facing a drastically changed environment.

In a human-centric version of a perfect world, within the multiple levels of homeostasis, environmental stress should be counteracted by epigenetic regulation; disturbances of metabolic status should be recovered; the errors of DNA replication should be repaired; altered cells should be eliminated by cell death mechanisms; abnormal clones should be constrained by the tissue architecture; and the formed cancer cells should be cleared up by the immune-system. In a cancer defined perfect world, in contrast, the break down of homeostasis is the key to success. Unfortunately, continually evolving systems are the way of life and cannot be totally prevented. In a sense, cancer is the price we pay for evolution as an interaction between system heterogeneity and homeostasis….

Facilitated Variation / Baldwin Effect

When changes are selected by the evolutionary process, these changes can be fixed either at a specific gene level or at the genome level (achieving the transition from epigenetic to genetic changes).

This is corroborated by Spencer, et al and Brock, et al, the latter of whom says, “‘pre-selection’ of non-genetic variants would markedly increase the probability of producing a random genetic mutation that may provide the basis for the survival capability of the original non-genetically variant outlier population.”

Path Dependence

…cancer cases are genetic and environmentally contingent. The pattern of specific gene mutations can only be used within a specific population with a similar genome, mutational composition as well as a similar environment.

…the stochastic events referred to here are not completely random but rather are less predictable due to differences in the initial conditions reflected by the multiple levels of genetic and epigenetic alteration.

From a system point of view, significant karyotypic changes represent a ‘‘point of no return’’ in system evolution, even though certain gene mutations and most likely epigenetic changes can influence karyotypic changes.

Upon establishment of a new genome through karyotypic evolution, it is impossible to revert back to a previous state through epigenetic alteration.

As long as the genome does not significantly change, epigenetic reprogramming could work to bring the system to its original status.

Multiple Levels

…the multiple levels of homeostasis are more important than genetic factors in constraining cancer, as alterations of system homeostasis rather than individual genetic alterations are responsible for the majority of cancers. Accordingly, the robustness of a network, the reversible features of epigenetic regulation, tissue architecture, and the immune-system will play a more important role than individual genetic alterations.

…genome level alteration within tumors is a universal feature.

Note that although physically the epigenetic level sits “above” the genome, functionally it’s really below, as indicated in this last figure. Of course, it helps to remind ourselves that “level” is a convenient but not quite accurate concept, and they are not always clearly distinct and non-overlapping, as in this case.

Current Methodological Weaknesses

It should be noted that these weaknesses stem from an inherent paradigmatic conflict that exists in science as it’s practiced today. These weaknesses will not be addressed until complex systems thinking pervades science in general.

…methodologies of DNA/RNA isolation and sequencing from mixed cell populations artificially average the molecular profile.

…current methods used to trace genetic loci heterogeneity are not accurate, as the admixture of DNA from different cells will wash away the true high level of heterogeneity and only display the heterogeneity of dominant clonal populations.

There is a need to change our way of thinking by focusing more on monitoring the level of heterogeneity rather than attempting to identify specific patterns in this highly dynamic process.

…the benefit of cancer intervention depends on the phase (stable or unstable) of evolution the somatic cells are in.

The strategies of attempting to reduce heterogeneity to study the mechanisms of cancer represent a flawed approach. Without heterogeneity, there would be no cancer. That is the reason why many principles discovered using simplified homogenous experimental systems do not apply in the real world of heterogeneity.

…cancer progression is fundamentally different from developmental processes…. The terminology ‘‘cancer development’’ implies an incorrect concept and needs to be changed.

…we recommend focusing on correlation studies rather than search for a specific ‘‘causal relationship’’.

…the understanding of the overall contribution of epigenetic regulation should not focus solely on tumor suppressor genes, but rather focus on system dynamics and evolve-ability.

]]>A true genome project would focus on the way genomic structure and topology form a genetic network and should also include epigenetic features of the genetic network.

- People of my generation (40 and older) who have capital they want to invest in innovation but only know the VC for-profit-only value model and don’t have any true view into or understanding of social entrepreneurship business models;

- People coming out of college today (27 and younger) who are actually creating untold value for the world without taking on investors because they don’t (a) know how to attract them, and (b) have heard too many horror stories

Jay and I fall into category 1 and Michael falls into category 2. All three of us agree that the gap above exists — due in part to rapidly declining startup costs — and represents a very real (and lucrative) investment opportunity if it can be closed properly. This opportunity is partly what the so-called “black swan fund” is tapping into as well, but I’m talking here of a distinct effort, which we want your feedback and participation on.

Creating a Workable Micro-Investment Model

Michael, Jay and I represent the three basic classes of people in this entrepreneurial ecology. Michael is an entrepreneur, I am a micro-investor, and Jay is person who sees and creates deal flow. We are trying to come up with a model that works, especially for Michael and myself — if it works for the two of us, Jay’s life becomes much easier and he makes more money. To these ends, I’ve outlined here the important elements of a micro-investment from my perspective (that of the investor). Hopefully Michael and others will chime in and say what’s important from the entrepreneur’s perspective (and what they need to motivate people on their team).

- I’d like to invest $1K to $5K in a number of different nascent “projects”.

- Monetary ROI potential is a necessary pre-condition for this activity, but it’s not my main motivation.

- The main “return” on investment for me is a combination of:

- catalyzing social good (40%)

- being “in the mix” on a social/business level (30%)

- feeling personally useful and productive in my life (20%)

- getting external ego validation (10%)

- The thing I want to invest in is a tribe in the Seth Godin sense. Tribes by definition coalesce around a leader (aka, the entrepreneur).

- I specifically don’t care about the legal structure or legal standing of the tribe. It can be a whole company, a project within a company, a de-facto, fluid, amorphous partnership of individuals, or a crowdsource. If successful, it will evolve into the correct formal/legal structure and I will trust the entrepreneur to honor the spirit of my investment in compensating me (see “moral integrity” bit below).

- I have to like and trust the entrepreneur first and foremost (and then I take it on faith that the tribe is reflective of that person’s values and energy).

- I will only invest in projects whose leaders I like personally and who have high moral integrity.

- I know I will be disappointed on the moral integrity front at some point by someone, and that’s okay. There will be zero tolerance for moral lapses: no more investment for such people, and they will be ostracized from my circle of influence.

- I am looking to get about 10% of the equity of the project for my initial investment of $1K to $5K.

- I expect the first look for follow-on funding if the project gets traction, and I understand the price will go up since the risk is lower.

- I expect the tribe to know if the project gets traction within about 3 months, if not it needs to be ruthlessly abandoned.

- I will not shed any tears and will praise the entrepreneur/tribe for making that tough decision rather than dinging them for “failure”. True failure — tragedy in fact — results from missing the real opportunities due to wasting time and money clinging to a bad or mediocre one.

- Since the cost for me to get in is about a tenth of the typical angel investment, I feel no qualms about doing little to no diligence or business model validation — in fact I feel liberated.

- Some entrepreneurs will ask for my strategic help (connections and advice) more than others. I will (mostly) give it on an as requested basis and not worry if a leader is not making the most of the relationship.

- Those that do leverage my strategic help are definitely more likely to get funded by me in the future, unless of course they make me a ton of money without it :-)

Three Paradoxes

Here are some paradoxical-seeming truths that I have come to believe through my past experiences, and which the above model of investing relies upon and leverages:

#1 I am more happy and motivated to strategically help projects that I put only a small amount of money into (or no money!) than ones I put a big amount into. With the latter, the leader needed to convince me they have a brilliant, solid business plan and know exactly how they are going to go from concept stage to being wildly successful over the course of 3 to 5 years. This, of course, is utter bullshit: no success story follows the original business plan. But having that CEO come back to me (after convincing me to plunk down $100K) and admit they have no idea how they will eventually be successful, that does not inspire confidence. With a micro-investment, I’m happy to throw it on the wall and see if it sticks. If not, let’s all move on — and let’s keep the kitchen open to make more pasta while we still have some dough, the water is boiling and the staff is happy.

#2 Making money has little to do with why I want to invest like this, but if the project does not have making profits as it’s #1 goal, I’m not interested. Why? Because I don’t think it will be successful in achieving the non-monetary goals either in that case. When I evaluate a project for potential investment, I will concentrate most of my decision on the money-making potential. But I will need to convince myself that the project is set up so that non-monetary goals are structurally assured if the money flows.

#3 By “overly” and “naively” trusting the entrepreneur with my money, I know that I will be paid back manifold financially in the long run. Because by giving this trust so freely (once I am convinced of moral integrity) I am invoking powerful social influence factors that will make the entrepreneur feel like treating me more than fairly whenever they have any discretion in making decisions that affect me. And by not boxing them in with rigid contractual obligations and manufactured incentive schemes, I am increasing the number of discretionary decision points the entrepreneur has.

If you are interested…

If you have actual experience as an entrepreneur or angel investor, I want to hear from you most of all. Please comment below on what parts of the above resonate with you and what parts do not.

If you have put serious thought into becoming an entrepreneur or making an angel investment but have never done so, I want to hear from you as well, especially the reasons why you haven’t (there are no wrong reasons).

If you don’t fit any of these categories, please don’t respond, your opinion is not relevant. I will update everyone on what ultimately transpires.

]]>I do believe that if we all followed the Golden Rule as the basis for how we treat one another the world would be a better place. But I also think there is a a more fundamental rule, call it the Diamond Rule, which is even better:

Treat others as you believe they would want you to treat them, if they knew everything that you did.

The difference is subtle, and may not practically speaking yield different action that often. But when it does, the difference can be significant.

]]>Lest you think the concept of Homo Evolutis — a species that can control its own evolutionary path by radically extend healthy human lifespan and ultimately merging with its technology — is a fringe concept share by sci-fi dreamers who don’t have a handle on reality, check out the list of people in charge of Singularity University (link above), the Board members of the Lifeboat Foundation, and throw in Stephen Hawking for good measure, who says, “Humans Have Entered a New Phase of Evolution“. These people not only have a handle on reality, they have the combined power, resources and influence to shape reality.

For those who are still skeptical of the premise of Homo Evolutis, I present the strongest piece of evidence yet: it’s been featured on The Oprah Show. QED?

]]>The article, “A New Phylogenetic Diversity Measure Generlizing the Shannon Index and Its Application to Phyllostomid Bats,” by Ben Allen, Mark Kon, Yaneer Bar-Yam, can be found on the American Naturalist website or, more accessibly, on my professional site.

So what is it about? Glad you asked!

Protecting biodiversity has become a central theme of conservation work over the past few decades. There has been something of a shift in focus from saving particular iconic endangered species, to preserving, as much as possible, the wealth and variety of life on the planet.

However, while biodiversity may seem like an intuitive concept, there is some disgreement about what it means in a formal sense and, in particular, how one might measure it. Given two ecological communities, or the same ecological community at two points in time, is there a way we can say which community is more diverse, or whether diversity has increased or decreased?

Certainly, a good starting point is to focus on species. As the writers of the Biblical flood narrative were in some sense aware, species are the basic unit of ecological reproduction. Thus the number of species (what biologists call the “species richness”) is a good measure of the variety of life in a community.

But aren’t genes the real unit of heredity, and hence diversity? Is the number of species more important than the variety of genes among those species? Should a forest containing many very closely related tree species be deemed more diverse than another whose species, though fewer, have unique genetic characteristics that make them valuable?

And while we’re complicating matters, what about the number of organisms per species? Is a community that is dominated by one species (with numerous others in low proportion) less diverse than one containing an even mixture?

There is no obvious way to combine all this information into a single measure for use in monitoring and comparing ecological communities. Some previously proposed measures have undesirable properties; for example, they may increase, counterintuitively, when a rare species is eliminated.

In this paper we propose a new measure based on one of my favorite ideas in all of science: entropy. You may have heard of entropy from physics, where it measures the “disorderliness” of a physical system. But it is really a far more general concept, used also in mathematics, staticstics, and the theory of automated communication (information theory) in particular. At heart, entropy is a measure of unpredictability. The more entropy in a system, the less able you will be to accurately predict its future behavior.

The connection to diversity is not so much of a stretch: in a highly diverse community, you will be less able to predict what kinds of life you will come across next. Diversity creates unpredictability.

To be fair, we weren’t the first to propose a connection between diversity and entropy. This connection is already well-known to conservation biologists. But we showed a new and mathematically elegant way of extending the entropy concept to include both species-level and gene-level diversity. It remains to be seen whether biologists will take up use of our measure, but whatever happens I am happy to have contributed to the conversation.

]]>You can donate here (I gave them $500), but make sure to write “For the Fisher Madagascar Project” in the “Comments” field. Otherwise, you’ll be paying for the building lights. Go ahead and leave the “Allocation” field at the default, “Campaign for a New Academy”. Update: Forgot to mention that if you donate $2,000 they’ll name a new species after you or whomever you designate.

It’s hard to do justice to what I saw last night in a blog post, but here goes…

First, you may be wondering what an ant taxonomist is doing saving the Madacascar rainforest. Well, it turns out that ant species are incredibly specialized to their local environment. (They are the prototypical superorganism after all.) So the density of ant species should be a major component of any good proxy for overall ecological diversity. Thus Brian and his team needed to visit the remaining rainforest to catalog the ants (and other insects). To accomplish this task, he’s become a combination of McGyver and Steve Wozniak: part super handyman and part super technologist.

The deforestation of Magacascar occurred over thousands of years as colonists from Asia pursued unsustaintable rice farming techniques. So the only rainforests left, are the ones that are hard for humans to get to and work on. He’s had to figure out everything from how to cross rivers in an SUV (lashing plastic containers to the bottom) to how to collect specimens from forest canopies in mountains (going up in a mini-dirigible).

Then he’s had to figure out how to catalog all the specimens and sort out the thousands species. He’s helped develop composite imaging techniques that give you a full view of specimens (check out AntWeb for some unbelievable pictures). He’s had to convince Google to change the Google Earth interface so you can see layers of information at the same location (making it possible for the rest of us to see multiple photos taken at the same spot, BTW). He’s had to improve DNA sequencing and comparison techniques. He seems to have adopted the Internet/Open Source model for much of his innovations so they have a lot of positive knock-on effects.

However, I think the coolest thing about Brian is his commitment to helping Madagascarans help themselves. He gets grants for the science and expeditions behind the species cataloging. But that doesn’t solve the preservation problem. So he’s helping create a local community of preservationists. He’s helped them create their own Madagascar Biodiversity Center. He’s bringing local scientists to the US to train and then return to increase the pace of work. He’s working with the government to finalize their countrywide preservation plan. For that, he needs our help.

(BTW, did you know that ants sleep and queens even dream? And each species of leafcutter ants has a corresponding unique fungus species that they “farm” as a “crop”? queens carry away a sample of the fungus as well as a dozen or so supporting microbe species in specialized pouches as a “starter kit” for new colonies. Wild and wacky stuff.)

]]>The first point to note is that the potential counterparty and I are good candidates for a bet. We both are acting as reasonable Bayesians (neither of us have extreme, ideologically-driven views). We both appear to have a decent grasp of the domain. We both have publicly stated our beliefs.

I believe that the underlying warming signal is +.05 deg C per decade and he thinks it’s +.15 deg C per decade. We have agreed that an over-under bet on a decadal trend of +.10 deg C is fair and that 2000 to 2020 should be the measurement period. So far so good. But now things get sticky.

We have to specify how to determine who wins the bet. Now, there’s no big red thermometer sticking out of the North Pole that shows the temperature for the entire Earth. So we have to choose a global temperature “product”. There are several alternatives: GISSTEMP, HadCRUT, RSS, and UAH. The first two use land-based thermometers and the second two use satellite-based microwave sensors. Neither approach is perfect.

However, I refuse to use any of land-based products as a reference for a bet on AGW. They tend to reflect land-use changes as much as climate changes. Two separate papers have concluded that about 40% to 50% of the warming signal from these sources could be attributable to increased economic development around previously rural stations. The actual “boots on the ground” issues with station siting are well documented here. Pave a road or install an air conditioner near a thermometer and voila, instant warming.

Satellite products are no paragon of accuracy either. They actually measure microwave radiation and use a model to infer the temperature. Several refinements over the years have corrected for things like orbital drift, which makes one wonder what other issues are lurking. Moreover, the record contains readings from several different satellites, each with multiple sensors (which degrade over time, BTW). The research groups behind the products use overlapping samples to calibrate new data streams, but that’s not a foolproof process by any means.

In the end, it comes down to coverage. Satellites gives us much denser, homogeneous, and consistent coverage of temperature readings. I think they are therefore much less likely to be systematically biased in detecting trends.

Unfortunately, our quest doesn’t end there. Satellites actually generate temperature data for several different altitudes and latitudes. Which of these best reflect AGW climatic processes? To find out, I consulted with Ross McKitrick and Roy Spencer, two well-known scientists with relevant expertise. You may remember Ross from this post. He proposes linking AGW-targeted interventions to the tropical troposphere termperature (T3) because all the climate models we currently have produce T3 warming as a unique signature attributable to CO2 increases. Unsurprisingly, Ross asserted that if the counterparty was unwilling to use T3, he didn’t really believe in significant AGW.

I take a slightly different philospohical posture from Ross. The scenarios where T3 is a signature of significant AGW are logically a subset of all scenarios where significant AGW occurs. Sure it could be the same set, but it could be smaller. Therefore, it would not be in the the potential counterparty’s strategic interest to limit the scenarios in which he wins. So I suggested we go with Roy’s suggestion of using the global lower troposphere series as most representative of the climate we care about.

There is one more wrinkle. I had originally suggested we use the three year averages around 2000 and 2020 as the basis for the bet. Given my academic background, I am a bit embarassed by this. Both Ross and Roy pointed out that this bet would be more about big climate events around 2020 than general trends. A big El Nino and I lose. A big volcanic eruption and I win. Not exactly the prediction we intend to measure.

They both suggested we calculate the linear trend from 2000 to 2020 using least squares regression. A decadal trend greater than .10 and I lose. Smaller than .10 and I win. This was the obvious approach in retrospect and I have suggested it to the potential counterparty.

More news as events warrant.

]]>I posit that the hotel I stay in (let’s call it the Imperial Palace) though low end by Vegas standards is nicer than the normal living quarters of 75% of the world’s population. Given that I am in the room to sleep and shower, do I really need a nicer place? Is it karmically bad to stay in a nicer place that I’m not really using?

We came up with the following idea. On my next trip I will stay at the IP again but donate half the difference between its cost and the cost at Caesar’s Palace to a charity for the homeless. So now my frugality has a point.

The accommodation scenario is easy. It gets more complex when I decide between Subway meatball subs and the meatball appetizer at Rao’s…

Thoughts?

]]>In an effort to make Centmail a reality, a formal protocol and API has already been developed. While I am somewhat worried that a large-scale adoption of the protocol will incentivize significant non-profit and charitable fraud, the economic burden due to spam should be greatly reduced. It’s a cool idea by good people and I urge you to check it out.

]]>Thanks to Marissa Chien who found it and pointed me to it. She also suggests that people who are having trouble with their mortgage should seek advise from HUD. Information is power and many people (I’ve learned) are irrationally scared of approaching their lender and negotiating. More and more lenders are willing to cut deals to avoid foreclosures.

]]>I’m usually not skeptical in this way, and I’m loath to focus on the negative when it comes to philanthropy, but I can’t get these thoughts out of my head and I’d like some perspective from those who are better informed about the alleged U.S. hunger crisis. In the mean time, here’s my food for thought:

- Generally speaking when I get a Facebook cause request it’s from a friend (or a Friend), but this one came from Causes itself: “Please join the Kellogg Company and Causes as we take small steps towards creating BIG change.”

- When you go to the Causes page it features a giant banner ad for Kellogg and Kellogg as the well-branded sponsor.

- Then when you go to the website the first thing that catches your eye is an image of this family who supposedly is suffering from hunger:

- On the Feeding America website I tried to educate myself on hunger facts but all I could seem to find was poverty statistics and stats related to food-related programs (like how many people used food stamps).

- I understand poverty is a big problem, but unlike in other parts of the world, starving in America is nearly impossible to do. A friend of mine who works tirelessly to provide meals to homeless admits that the food is just a hook to get folks into a graduated self-sufficiency program.

- Being malnourished in the U.S., on the other hand, is becoming increasingly easy to do, especially if you eat Kellogg products which have very few nutrients relative to whole foods, particularly veggies and fruit. Malnutrition in the U.S. manifests itself differently than in poor countries though: obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, heart disease, cancer, et al.

- I went to Charity Navigator to look into the Feeding America and was surprised to find it gets great marks. I was even more surprised to find that its revenues are $650 Million per year(!) And since they have such an incredibly low overhead rate and spend nearly 97% of all money raised directly on programs to feed the hungry, I’m flabbergasted. Hunger must be a huge and totally unappreciated problem in the U.S. if it can’t be solved with the billions spent trying.

- Looking at the breakdown of the $650M in revenue from their annual report, $560M of it is from “Donated goods and services”. Presumably that’s good and efficient. However I can’t help but wonder how much of that is food grown with subsidies from the government, which then Kellogg writes off against its taxes as an in-kind donation. Does anyone know whether this is the case?

I expect to be taken to task on this, but isn’t it really just a PR move by big businesses who’d rather give away product rather than feed people farther from home at greater expense (or better yet help them become self-sustaining)?

]]>Other ideas include spraying sulfur dioxide 65,000 feet up through a fleet of Zeppelins and firing 840 billion ceramic frisbees into orbit to block the sun’s rays. But this article also suggests that a rich “Greenfinger” could unilaterally do some Geo-Engineering without world consent and with disasterous consequences.

]]>Check out this even more interesting way of generating solar power at Cool Earth Solar. It is massively scalable and can compete on price with traditional sources.

]]>It turns out you can sell as many CDSs on the same mortgages as you want. So Amherst sold more CDSs than the face value of the mortgages. Way more as it turns out. Then they simply bought up the loans and paid them off. No default, so the CDSs don’t pay out. They pocket the difference between the value of the CDSs they sold and the face value of the mortgages they had to buy up. About $70M according to this report.

Of course, the Wall Street wizards are calling foul. This is silly because if each of them had only bought enough CDSs to cover his own exposure, they all would have been fine. But they got greedy and thought they’d try to take advantage of Amherst by buying several times as much coverage as they needed. My wrestling coach had a piece of advice for what to do when your opponent makes a monumental mistake. “NEVER give a sucker an even break.”

]]>

Mission critical at Quest is a translation of the underlying form of games into a powerful pedagogical model for its 6-12th graders. Games work as rule-based learning systems, creating worlds in which players actively participate, use strategic thinking to make choices, solve complex problems, seek content knowledge, receive constant feedback, and consider the point of view of others. As is the case with many of the games played by young people today, Quest is designed to enable students to “take on” the identities and behaviors of explorers, mathematicians, historians, writers, and evolutionary biologists as they work through a dynamic, challenge-based curriculum with content-rich questing to learn at its core. It’s important to note that Quest is not a school whose curriculum is made up of the play of commercial videogames, but rather a school that uses the underlying design principles of games to create highly immersive, game-like learning experiences. Games and other forms of digital media serve another useful purpose at Quest: they serve to model the complexity and promise of “systems.” Understanding and accounting for this complexity is a fundamental literacy of the 21st century.

Elsewhere they go into a bit more detail about how games are used to teach different subject areas:

At Quest students learn standards‐based content within classes that we call domains. These domains organize disciplinary knowledge in 21st certain ways—around big ideas that require expertise in two or more traditional subjects, like math and science, or ELA and social studies. One of our domains— The Way Things Work—is an integrated math and science class organized around ideas from design and engineering: taking systems apart and putting them back together again. Another domain—Codeworlds—is an integrated ELA, math, and computer programming class organized around the big idea of symbolic systems, language, syntax, and grammar. A third domain—Being, Space and Place—an integrated ELA and social studies class—is organized around the big idea of the individual and their relationship to community and networks of knowledge, across time and space. Wellness is the last of our integrated domains, a class that combines the study of health, socio‐emotional issues, nutrition, movement, organizational strategies, and communication skills.

OMG!OMG!OMG!OMG!

One of my favorite aspects of this school is that they have a separate staff of game designers working together with their teachers. As a former teacher I can tell you that designing good, creative lessons is a relatively different skill-set from actually implementing these lessons in front of a class and following up with your students, and that doing both well requires more time than is physically possible without traveling at relativistic speeds. So having designers who are there at the school and understand the teachers’ needs, and who have the time to make great lessons, is a really really good idea.

]]>hat tip: Annie Duke’s mom

]]>Alexander (a pseudonym) is an Air Force interrogator with a criminal investigation background. He was brought in as part of team trained to employ “new school” interrogation techniques in Iraq, post-Abu-Ghraib. These techniques focus on building rapport with prisoners and gradually winning their trust, instead of trying to establish dominance and control over them. The book is about his unit’s successful search for Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, the head of al-Qaeda in Iraq.

There isn’t a lot of door-kicking, badass-combat action. It’s a psychological workplace thriller. But the fact that I lived through the context of how important the mission was makes it rather heart pounding. It’s fascinating how well the new school techniques work on supposedly hardened al-Qaeda operatives and how resistant the old school practioners are to using them. The story also provides some insight into how primate politics can infect even the most clear and critical missions. In fact, a crucial advance in the search comes from Alexander bucking the political order at great risk to his career.

There’s some nice humor too. “Randy” is the ex-Special-Forces commander of the interrogation unit. He has a reputation as something of a badass. So a “Randy-ism” will occassionally and anonymously appear on the whiteboard. My favorites:

“Jesus can walk on water, but Randy can swim through land.”

“When Randy wants vegetables, he eats a vegetarian.”

“Little boys check under their beds at night for the bogeyman. The bogeyman checks under his bed for Randy.”

Next time I have to interrogate a prisoner, I’ll have some idea of what to do.

]]>I happen to be one of 53 lucky graduate students to be selected for this year’s Young Scholars Summer Program, meaning I get to paid to live in Vienna and do research. Can’t really complain about that. Tomorrow I get to hear mini-presentations on everyone’s research proposals, which should be very interesting. My own project will be on the long term, gradual evolution of cooperation in spatially structured populations, using a mathematical framework known as adaptive dynamics.

I’m expecting to learn a lot here, and I’ll share as much as I can with you readers. Looking forward to it!

]]>

Prediction markets occasionally exist concerning a single event of an individual company, but this represents only a fraction of the market opportunities that can be made available. I propose creating a large number of prediction markets, perhaps 500-1000, covering all types of companies: Those near liquidity like Facebook and Twitter, those that recently received Series A or B venture financing, and even those that are running on seed or angel funding, or with no outside investment at all. Each company could have a series of markets to assess its current value and prospects for success. While verifiable information concerning private companies is often hard to come by, there are a variety of metrics that could be used as the basis for markets:

– If and when a company goes public, as well as its closing IPO valuation

– If and when a company is sold, as well as its sale price (if disclosed.)

– Number of registered or active users.

– Website traffic (this is most applicable for certain types of companies, like Social networking)

I like to think there are many more applicable measures of success that can be used and would love to hear any suggestions from our readers. Most likely each sector has some specific metrics that are applicable to evaluating success or failure. With enough volume, a market for valuing private companies would emerge. This might not be as far off as you think.

The Commodity Futures Modernization Act allows for real money prediction markets that operate as an Exempt Board of Trade (EBOT.) The American Civics Exchange (ACE) is one of the first companies to take advantage of EBOT status. While today they have only a few markets, which concern tax changes and other political actions, they anticipate expanding to include contracts that allow individuals and business to hedge against a legitimate risk. Examples could include FDA drug approval, the outcome of major class action lawsuits, and even health care reform. Unfortunately, trading in these markets is restricted to high net worth individuals, and contracts relating to the success of private companies is likely prohibited. Still, this exchange represents a step in the right direction.

Recently, Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft co-wrote a letter to the Commodity Futures Trading Commision (CFTC) asking for “small stakes” real money prediction markets. They believe that real money prediction markets have the “potential to provide significant public benefit.” My guess is they believe there is significant money to be made as well, but that is ok with me. Momentum is building, and an actual real money stock market for private companies may not be far away.

While I would like to personally bet on the success and failure of many companies, I’m also curious how accurate the markets will be in predicting success. I think that the younger (not necessarily in absolute time) a company is, the less predictable its prospects become. Kevin Dick believes small groups like angel investors and venture capitalists can’t pick winners at the seed stage. But what about large groups and the “wisdom of crowds”? Perhaps aggregating information via prediction markets can yield better signals about a company’s prospects for success. Assuming it can, this data will be of interest to a number of parties including potential acquirers, partners, analysts, and even customers. You don’t really want to use a company’s products if you think they are going bust, do you? Today, if you have that opinion, there isn’t much for you to do other than decline to buy its products. But soon you might be able to bet on it and turn a profit.

]]>Yesterday, he put up a post titled CO2 Warming Looks Real. He’s not an expert. Like me, he has an economics background and did some detailed research. Yet from the title and body of the post, I though he must have reached a very different conclusion than I did. So I thought I’d try to engage him to find out where we differ. The results were interesting.

Obviously, and as Robin knows, the best way to elicit a person’s true beliefs is to observe where he puts his money. So I offered to negotiate a bet of up to $1,000. As you can see from reading the comments, he eventually offered an even-odds bet than the temperature would rise 0.1 deg C in 20 years. Yes, you read that correctly: 0.1 deg C.

So he’s as much of a skeptic as I am! I think a doubling of CO2 concentration would lead to about 1 deg C of warming. I think, it’s going to take about 200 years (from 1900-2100) to do that. So I believe that we should see warming of about .05 deg C per decade. In 20 years, that’s about… 0.1 deg C. (Yes, I know I’m linearly approximating a logarithmic function, but the amount of precision in all the input values is low enough that I don’t think it matters).

Now, as I pointed out to Robin, the official IPCC estimates are much higher. If you go to the latest Summary for Policy Makers and look at Table SPM.3, you see the rate of warming in the lowest impact scenario B1 is 2x to 5x higher. So Robin’s price reveals that he is quite skeptical of the IPCC estimates.

Moreover, if you believe that the over-under on temperature in 2100 is .45 deg C higher than today, why would you think that justifies any significant mitigation effort? To the extent that there are any costs, we could certainly pay them at a fraction of the economic cost of a carbon tax or cap-and-trade. Moreover, you’re saying that GHG emissions account for only a small part of the variance in future temperature. So it could get a lot cooler as well as a lot warmer. Seems like that implies we should save our money for adapting to whichever way the thermometer swings.

Personally, I’m pleased to know that Robin Hanson did not reach different conclusions from me and that, by my definition, he is a fellow member of the “well-informed skeptic” club.

]]>

As Krisztina Holly discovered on her recent visit,”there are no directors. No CEOs or presidents.” And

Because their community is close-knit and their most valuable currency is reputation, experimental physicists around the world know who contributes. Conversely, the few who have been too proprietary with their ideas have been ostracized. It’s like a crowd-sourced performance review.

Interestingly, because of such thorough amounts of collaboration, Holly points out that it’s unlikely for anyone to win the Nobel Prize. My favorite part of the LHC though is the (clearly) crowdsourced website.

As an aside, I was curious what the prediction markets think of the likelihood is of finding the Higgs boson (the last unobserved particle predicted by the Standard Model). Surprisingly, given how important this proposition is to the future of science, there is very little action on it. Intrade.com has two bets: will it be discovered before the end of 2009 and will it be discovered before the end of 2010. Based on the historical price of these — the latter was a 4-1 favorite as recently as last fall — it seems as though the low odd currently (10-1 and 4-1 against, respectively) has to do mostly with the timing of the discovery and not whether the discovery will happen. Personally, I’m willing to bet against the Higgs boson’s existence if given 4-1 odds, so anyone looking for some action on this, let me know.

]]>Still, I can’t help but feel that the focus on Creationism’s pseudoscientific claims have obscured what is really a debate about beliefs and values, not science. Moreover, the discourse on blogs often reflects a view that religion (of all forms) is inherently opposed to evolution, and that no intelligent person could possibly believe in both.

My partner addressed some of these issues in a final paper for her recently completed Master’s of Theological Studies degree from Harvard Divinity School. This paper begins with an anecdote describing the surprising and complex position toward evolution taken by middle school students she taught, and goes on to detail the history of Catholic responses to Darwin’s theory. Some of the ideas from her paper are articulated below in the hopes of adding nuance to the evolution blogversation. Neither she nor I intend to present either her students’ view or the Catholic view as models for how to reconcile (or not) evolution and faith, but only as voices that complexify the picture of this conversation as a fight between Bible-thumping evangelists on the one hand and atheist scientists on the other.

….

In 2004 I was a new, white teacher at a middle school in Dorchester, Massacusetts. The students in my seventh and eighth grade comparative religions classes were young women of color, and of primarily African and Caribbean descent. During the kind of cheerfully chaotic class that takes place the day before a lengthy school holiday, one of my most inquisitive students surprised me with a question about evolution. She wanted to know who was right: the scientists, or the people we were studying in religion class? Before I could collect my thoughts, a flood of powerful and emotional rejoinders issued from several of her classmates. My limited familiarity with the traditions with which they were affiliated gave me only a vague sense that I might expect a critical stance on the subject. What I had entirely failed to consider were the ways in which the cultural and racial identities of my students intersected with both their religious worldviews and their feelings about evolution. I soon learned that the ways in which many of these young women processed the tense public controversy over evolution and Biblically based accounts of creation were deeply tied to their sense of identity as people of color in a white-dominated culture. Many began quoting their pastors: “You are made in the image of God. You are beautiful, loved, and wanted in this world, and can’t nobody take that away from you.” Others followed with similar, powerful words that affirmed the essential pride and self worth that was instilled in any child of God. Still other students spoke of the historical influence of this notion of essential human worth on abolitionist and civil rights movements. They knew their history. The concept that all humans have been made with great love and purpose by God has historically operated as a powerful political and psychological resource to combat the behaviors of a racist society. Many students made it clear that they saw the promotion of evolutionary theory as a direct attack on the foundations of their personal identity, faith, and value as human beings.

Though I felt moved and honored to hear the powerful and nuanced ways in which my students articulated the liberative power behind the Biblical account of creation, I was pained to hear how rigidly and antagonistically they conceptualized the “evolution side” of this conversation. I found their monolithic image of “evolutionists” to be a clear example of the troubling state of an important conversation. These young women’s understanding of the relationship between evolution and faith led them to conceive of the scientific claim as only another attack on their sense of self by a hostile, dominant majority 1. Such an understanding represents a disconcerting deficit of education on both sides of the conversation, effectively eclipsing a range of voices from adding texture to what has become yet another American clash of extremes.

Most contemporary public discussion and media attention on the subject has been shaped by the polarizing rhetoric of certain anti-evolution Protestant American Christians. Those who oppose these efforts by criticizing creationist “science” have largely fallen into the trap of engaging in only reactionary responses. Many on both sides have portrayed this conversation as a conflict of “religion versus science,” ignoring the fact that the Creationist movement has historically been a uniquely American Protestant phenomenon 2, which has only in the past couple decades begun to spread to other countries 3.

Ironically, included in the crowd of voices with which my students were unfamiliar were those from the Catholic Church, the tradition upon which their school was founded. Indeed, when I related my classroom conversation to some of my fellow teachers, most of whom were raised within the Church, they expressed great surprise, recalling that the science classes within their own Catholic education had included extensive coverage of the scientific theory of evolution. (In fact, a survey of American Catholic school textbooks published between 1940-1960 found them to be in closer agreement with evolutionary theory than American public school textbooks from the same period 4.) Intrigued, I looked further into the historical response of the Catholic Church to Darwin and found a complex story that most certainly disrupts the largely monolithic representation of Christian responses to this scientific theory. It is also a story that is infrequently told, and appears to be largely unfamiliar to much of the American public 5.

For almost a full century following publication of “Origin of the Species,” the Church hierarchy avoided any official stance on, or condemnation of, evolution. The first official Vatican pronouncement, Pope Pius XII’s 1950 encyclical, Humani Generis (Human Origins), ackowledged evolution as a possible scientific explanation for the origin of humanity6. More recent pronouncements have strongly embraced evolution as a scientific theory, as evidenced in Pope John Paul II’s 1996 address to the Pontificate Academy of Sciences, the current Pope Benedict XVI’s text “Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons created in the image of God,” and the 2009 Vatican conference on “Biological Evolution: Facts and Theories.” These documents express the view that evolution can be regarded as both a random process in the scientific sense, as well as a fulfillment of God’s plan7. Thus, while the Church accepts evolution as a scientific theory, it rejects any claims that this theory has no place for God. Significantly, these documents seek to distance the Catholic perspective from that of intelligent design Creationists8, and intelligent design speakers were pointedly barred from the recent Vatican conference.

Popular thought about evolution amongst American Catholic laity, scholars, and journalists has been largely supportive of evolutionary theory as well. A literature review of popular Catholic press indicates that responses to the 1925 Scopes and 2005 Dover trials (the former testing a Tennessee prohibition against teaching evolution in public schools, and the latter arguing against the inclusion of intelligent design within public school science curricula) demonstrates a desire to problematize any claims of an inevitable clash between science and religion brought about by the teaching of evolution9. For example, one 1925 editorial in a Catholic newsletter argued “[Creationist lawyer] William Jennings Bryan is reported as having said that if evolution is true, then Christianity can’t be true. In this matter as well as many others Mr. Bryan is wrong.” 10

….

The full text of the paper, which delves more deeply into how science becomes appropriated as a “cultural resource” and gives recommendations for teaching, can be made available on request. Again, our purpose is not to espouse or promote the Catholic view, but merely to present it as evidence that Creationists do not represent all, or even most, religious (or even Christian) views on evolution, and to highlight some of the hidden cultural factors underlying this debate.

Footnotes:

1 While I affirm that it is crucial for my students to develop a more nuanced understanding of the scientific community, it is important to note that, as young women of color their anger and anxiety is certainly not unfounded. The history of science as practiced by dominant culture is guilty of repeatedly producing scientific data and discourse in ways that either exploit or promote racist ideology. The American eugenics movement and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study are but two examples of this phenomenon.

2 Eugenie C. Scott, Evolution vs. Creationism (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004), 85-134.

3 Simon Coleman and Leslie Carlin, Cultures of Creationism (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), ix.

4 Gerald Skoog, “The Coverage of Human Evolution in High School Biology Textbooks in the 20th Century and Current State Science Standards,” Science and Education 14(2005):412-413.

5 Ronald L. Numbers and John Stenhouse, eds., Disseminating Darwinism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 2. This text is one of many that notes the lack of both scholarly research and public knowledge on the Catholic position toward evolution.

6 Humani Generis, Chapter 36.

7 “Communion and Stewardship,” Chapter 69.

8 Ibid.

9 Christopher M. Hammer, Reconciling Faith, Reason, and Freedom: Catholicism and Evolution from Scopes to Dover (MA Thesis, University of Virginia, 2008), 3.

10 F. Gordon O’Neil, “The Week,” Monitor and Intermountain Catholic, June 6, 1925, 1.

]]>More likely, you’ve probably heard of private investors taking advantage of the banks’ unwillingness (or inability) to deal with all the bad loans on their books. Like the group of investors in Act 2 of this This American Life episode, you buy a house that’s in foreclosure for a significant discount on its true market value and then “you get the homeowner into either a mortgage they can afford, or they’re able to rent it, or you pay them a bit to move somewhere else.”

Well, what if there was a way to combine these two activities so that you are doing good for someone else while doing well for yourself financially? There are many variants of how this could work, but here’s the basic concept:

- Identify a number of people who are about to be foreclosed on but who could afford a reduced mortgage (or rent), and who want to stay in their homes.

- Buy these homes at a deep discount either from the bank directly or at auction. E.g. Owner owes $300K, monthly payments are $2K, house is now worth $200K, you get it for $150K.

- Offer the original home owner one of two options:

- Get a new loan to buy it back from you at $175K

- Rent it from you for $1K until such time as they can afford to buy it back at a guaranteed $25K below the appraised value at that time.

The key thing to keep in mind is that you half doing this to make a profit and half doing it philanthropically to keep the borrower from losing their house. So whatever potential profit the bank is leaving on the table by not being flexible, you keep half and the borrower gets the rest of the value. Note that the “rest of the value” to the borrower is actually higher than what either you or the bank could capture because they probably owe more than the house is currently worth. In the example above, instead of owing $300K, if you flip the house back to the borrower at $175K, they’ve just made $125K. You’ve made a very quick $25K just by being in the right place at the right time with cash (and a willingness to hold the property and be a landlord).

I can envision a web site where people who are about to lose their homes can register, giving all the details of their property and sale history along with the history of the relationship with their lender, what their current and prospective financial picture looks like, and how much they would be willing/able to spend monthly on a new mortgage or rent. The story is vetted and the applications that are suspect or don’t meet the criteria are rejected. The candidates that pass are given a “buyback or rentback” offer conditional on you being able to get the property at the target price or lower.

Please comment below if you’ve heard of anyone doing this.

If you haven’t and you are a home owner who would be a candidate for this type of deal, please also speak up. You might just find your Robin Hood, or maybe a group will emerge to create a fund for this.

If you are a potential investor in such a fund, let us know.

hat tip: Laura Rose, Marissa Chien

]]>First, let’s look at the issue of spending as a percentage of income. As Eric Rescorla pointed out to me in a personal communication, one could contend that state and local spending should remain constant as a percentage of income. Budgeting a fixed share of our resources to state and local projects seems prima facie reasonable. According to this site, per capita income in California was $42,696 in 2008 and $28,374 in 1998. Using our handy-dandy inflation calculator to convert both of those to 2009 dollars, we get $42,287 for 2008 and $37,119 for 1998. That’s real growth of 14% over 10 years (yes, a very slightly different 10 years than the budget numbers I have, but close enough). So real per capita spending grew at 2.7x the rate of real per capita income.

Next, Terence posted in the comments that he had probably tracked down the two largest sources of spending increases: incarceration and education. His numbers look pretty convincing. Now, I think we can probably agree that incarceration is not a good. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. California’s is actually higher than the national average. I don’t think Californians are 5x as anti-social as the British, who have about 1/5th the incarceration rate (but still the highest in the EU). So I’m pretty sure this is not an efficient use of our money.

That leaves us with education. Is increased education spending a good? From first principles, it seems like it should be. Given the large positive role it has played in my life, I hope it would be. The evidence is that additional years of education produce a positive return. However, this is somewhat different from the question of whether more public spending leads to better results. Alas, on this point, the evidence is alarmingly weak.

According to the official state statistics, the California graduation rate in 2007-08 was 79.7% compared to 83.3% in 1997-98. Going down, not up. But perhaps it takes time for increased spending to affect the graduation rate. In that case, we might want to look at intermediate metrics.

The standard benchmark here is the National Assesment of Education Progress. These are standardized tests of academic knowledge given in different subjects at different ages. Reading test data goes back to 1971. Math test data goes back to 1978. These appear to be the most consistent metrics we have available. You can visually inspect the California results here. Unfortunately, they only gave certain tests in certain years so the time periods don’t quite match up with the budget data.

What you will see is that from 1996 to 2007, math scores for Grade 4 rose from 209 to 230 (10.0%) and for Grade 8 rose from 263 to 270 (2.7%). From 1998 to 2007, reading scores for Grade 4 rose from 202 to 209 (3.5%) and for Grade 8 dropped from 252 to 251 (-0.3%). This looks like a rather slight improvement for the amount of money spent.

Of course, visual inspection is not very rigorous. You want statistical analysis. Well, it turns out that there is a nice Brookings publication on the topic for the whole United States. The introduction is available via Google and worth reading because it walks through the research history. The summary is that there has been a lot of academic back and forth on the relationship between education resources and results. My take is that many decades ago, there was a weak yet significant relationship. But it has mostly evaporated as the level of expenditures rose above some threshold level. Perhaps the most interesting bit is about a “natural experiment” where 15 Austin, TX schools had a substantial increase in the resources available to them. Student performance increased at only 2 of the 15 schools.

I found a more specific 1999 paper on spending and achievement in California. The full text is behind a paywall, but the abstract says, “The evidence indicates that, despite claims to the contrary by many advocates of public education, higher education spending does not raise student achievement. Education spending is also shown to be highest in those counties exhibiting highest monopoly power as measured by the Herfindahl index.” Basically,I think this means that education spending is driven by how powerful the local public school system is.

All in all, not good news. We’re spending more than we’re making. The increase is split primarily between a “bad” and a “good”, but even the “good” spending doesn’t seem very effective. I just don’t feel that I’m getting my money’s worth.

]]>One became super efficient at gobbling up its food, doing so at a rate that was about a hundred times faster than the other. The other was slower at acquiring food, but produced about three times more progeny per generation.

The answer is…

RNA molecules which self-catalyze and evolve in the lab. This gets us one step closer to being able to show how life could have emerged on Earth without any endogenous materials (e.g. asteroids crashing into Earth carrying DNA).

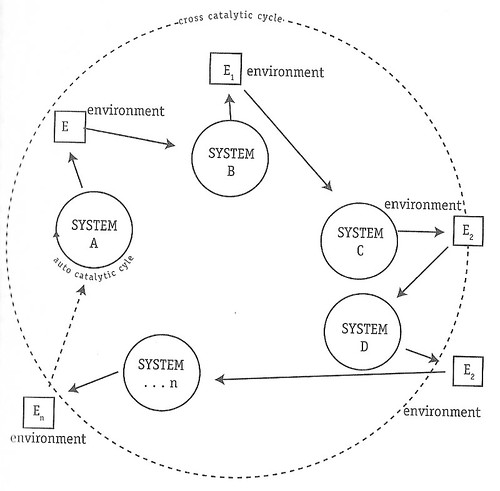

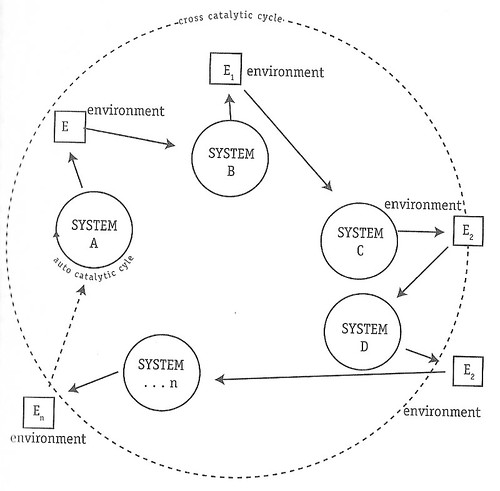

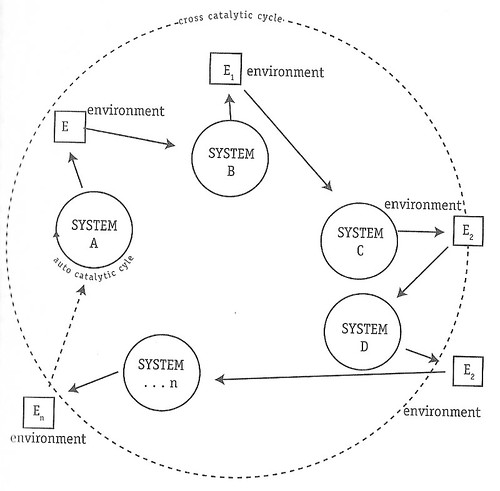

I’ve never understood why such “exogenous origins” theories are popular since they seem like a pseudo-creationist punt rather than a truly scientific view. Sure, DNA could have come from outer space. But Stuart Kauffman showed years ago how — conceptually speaking — autocatalysis and cross-catalytic reactions could yield self-replicating molecules. Now all that’s left is setting up the right initial conditions to show the existence proof. No aliens — or god(s) — necessary.

]]>2. Spend time with friends, or even try and make a new one.

3. Help another person. Donate a small amount of money, that has nominal value to you, but significant value to someone else. (Kiva, Vittana Foundation.)

4. Quit Smoking. It might be even worse for you today.

]]>One became super efficient at gobbling up its food, doing so at a rate that was about a hundred times faster than the other. The other was slower at acquiring food, but produced about three times more progeny per generation.

Answer in tomorrow’s post.

]]>

In an excellent column in today’s Washington Post, Courtland Milloy explores the use of the war metaphor, and how it can be better used, if need be.

In an effort to recast substance abuse as more of a public health problem than a crime, the nation’s newly appointed drug czar has called for an end to talk of a “war on drugs.”

“Regardless of how you try to explain to people it’s a ‘war on drugs’ or a ‘war on a product,’ people see a war as a war on them,” Gil Kerlikowske, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, told the Wall Street Journal last week.

Wow. War scares me too. But is it really over? Will we stop jailing non-violent offenders? Can we now focus on treatment?

Via the Huffington Post, Jack Cole, Executive Director of Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP,) doesn’t think the war is over:

A rose by any other name. This is not a war on drugs, it is a war on people; a war on our children, our parents, ourselves. Rebranding won’t change things. A new policy is needed to change things; ending drug prohibition.

Rebranding, a classic marketing trick. Sometimes a new name is all it takes to turn an unsuccessful product into a superstar. Somehow, I do not think this gambit will work here. And, whatever we call it, resources are still being disproportionately devoted to this “war.” According to Milloy, the Obama administration is spending more than double the National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA) annual research budget to “enhance Mexican law enforcement and judicial capacity.”

So the war is not really over. But, we can focus more of our resources on treatment, and attack the problem where it really lies, the brain.

Milloy concludes:

]]>But a battle rages nonetheless. And he’ll [Kerlikowske] need to rally the troops. For the foe is cunning, capturing the brain. In a war, that would be the strategic high ground, and it must be retaken if we are to win.

In honor of California’s special election on budget measures, I thought I’d shed a little light on the fundamental problem. Contrary to what polticians are saying, the cause of the budget problem is not falling revenues in a recession. Rather, the cause is a dramatic increase in spending over the last 10 years.