| CARVIEW |

Last December I spent a week in a refugee camp in the Algerian desert. The camp I was staying in is one of five camps that are home to some 200,000 people displaced by Morocco’s invasion and continuing occupation of Western Sahara, designated as a non-self-governing territory by the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization since 1963.1 On 1st June, the UK government effectively endorsed Morocco’s occupation of these refugees’ homeland in exchange for the promise of access to lucrative contracts for British businesses. The news of this arrangement came in the form of a UK-Morocco Joint Communiqué describing a new partnership between the two countries, reported by the Financial Times and the BBC but otherwise receiving little coverage.

Referring to the promise of access to critical infrastructure contracts related to Morocco’s hosting of the 2030 World Cup, British Foreign Secretary David Lammy said that the new arrangement with Morocco would “directly benefit British business,” with British companies being “at the front of the queue to secure contracts to build Moroccan infrastructure, injecting money into our construction industry and ensuring that British businesses score big on football’s biggest stage.”2 The UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) stated that this latest agreement, predicated on the UK’s support for Morocco’s position on Western Sahara, would “create a unique foundation for UK companies to access public tenders in Morocco.”2 In return, the communiqué praised Morocco’s ‘autonomy plan’ for Western Sahara as “the most credible, viable and pragmatic basis for a lasting resolution” to the Western Sahara conflict. Critically, this autonomy plan is a unilateral initiative by Morocco that rules out a referendum on self-determination as mandated under international law, excludes the exiled Sahrawi refugees and their representatives from the political process, and ignores the fact that Western Sahara is physically partitioned (more on all this below). These statements could not make any clearer the transactional nature of the new agreement, with Morocco using public procurement processes to purchase UK support for its position on Western Sahara.

This is all very familiar to anyone who pays attention to the Western Sahara conflict, as it echoes the deal Donald Trump made with Morocco in 2020 in the guise of the Abraham Accords. As part of this deal, the United States recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in return for Morocco normalising its relations with Israel, allowing Trump to present himself (temporarily at least) as a peacemaker in the Middle East. The new agreement between London and Rabat enables the governing Labour party to present itself as a champion of British business and the ‘party of growth’ at a time of economic stagnation at home. Some commentators have characterised Labour’s approach to the economy as one based on ‘growth at all costs.’3 4 Whilst certain constructive mechanisms that would guarantee growth, such as a much closer relationship with the EU, have been ruled out for political reasons, more destructive ones such as the rolling back of environmental protections have been embraced by the Labour leadership.5 6

This new deal with Morocco is similarly destructive, and its costs are likely to be high, not just for the Sahrawi people living in exile as refugees or under Moroccan occupation, but also for the waning authority of international law, the UK’s reputation, and political stability in the wider northern African region.

The most obvious cost is borne by the Sahrawis themselves. The UK’s formal endorsement of Morocco’s claim to the territory is another sorry episode in the appeasement of the Moroccan state that places any meaningful resolution of the conflict further out of reach and condemns the Sahrawis to indefinite occupation and exile. Lammy’s shameful deal comes in the 50th year of the occupation, under which Moroccan security forces routinely beat, torture and sometimes murder Sahrawis who dare express any desire for self-determination. Outside occupied Western Sahara, most Sahrawis live as refugees in the increasingly hostile desert interior, where climate change is subjecting them to worsening heat extremes and increasing water scarcity. Trapped in a climate risk hot-spot and denied formal statehood, they are locked out of global climate governance and finance mechanisms that might otherwise support them to adapt. In contrast, Morocco has positioned itself as a climate leader, accessing significant amounts of climate finance. However, this does not benefit the Sahrawis. In the Occupied Territories, Moroccan authorities are demolishing Sahrawi homes to clear land for renewable energy projects with which it hopes to burnish its green credentials and lock its neighbours into energy dependence on the occupation. At a time when many governments, NGOs and multilateral organisations are emphasising the need for a just transition to a resilient, low-carbon world, the Western Sahara conflict is an exemplar of climate injustice and the amplification of vulnerability through conflict and marginalisation.

My recent trip the refugee camps was occasioned by a conference on international law and the Western Sahara conflict, at which I had been invited to speak about the implications of climate change for the territory and its people. Its designation as a non-self-governing territory means that, in the eyes of international law, the decolonisation process in the Western Sahara is not yet complete, and that its people are entitled to the right of self-determination. This right is intended to be exercised through a referendum has been recommended by the International Court of Justice, mandated by the UN, written into the mandate and title of the UN peacekeeping force in Western Sahara, and reiterated by several resolutions of the UN General Assembly.7 Crucially, Morocco’s so-called autonomy plan, endorsed by the UK government as part of the latest deal, has no provision for a referendum on self-determination, let alone the prospect of independence, which Morocco has repeatedly ruled out.

The UK’s recognition of Western Sahara as part of Morocco presumably means that the British government will make no distinction between Morocco and Western Sahara when it comes to trade and business. This would pit the UK government against international law as it relates to the exploitation of occupied territories.

A key principle of international law is that any exploitation of a territory by its occupier must benefit the people of that territory, and that those people should consent to any treaties or agreements that affect them as a third party. This principle was tested in 2024 by the Court of Justice of the European Union, when the Polisario Front, the Sahrawi national liberation movement, challenged fisheries and trade agreements between Morocco and the EU. The Court confirmed a 2021 decision of the European General Court annulling these agreements on the basis that they did not benefit the people of Western Sahara, who had not given their consent for such agreements. The Court recognised the Polisario’s legimacy as a representative of the people of Western Sahara, which, notably, it defined as comprising the indigenous Sahrawi population rather than the wider population, now dominated by Moroccan settlers.8 If the putative business deals touted by Lammy and the FCDO involve operations in occupied Western Sahara, the UK government may be open to similar legal challenges to those brought against the EU.

Undermining the rules-based international order and the UK’s reputation

The UK-Morocco communiqué states that both countries “reaffirmed the paramount importance of a rules-based international order and the fundamental principles of the Charter of the United Nations.” This statement should be taken with a huge pinch of salt. The invasion and continued occupation of Western Sahara in itself is a direct snub to the rules-based international order, as is the UK’s endorsement of Morocco’s position. Morocco rejected the 1975 ruling of the International Court of Justice that it has no legitimate claim to Western Sahara. It has ignored multiple United Nations resolutions on decolonisation and the referendum, as well as the rulings of European courts on the legitimacy of trade agreements and the requirement for Sahrawi consent to these (see above).

Far from reaffirming the importance of a rules-based international order, the UK’s new support for Morocco’s position on Western Sahara is another nail in its coffin. At a time of increasing global insecurity, when preserving this order is absolutely vital, this agreement sends a dismal message to other governments that might want to invade and occupy their neighbours. Tellingly, the communiqué follows its disingenuous endorsement of the rules-based international order by stating that both countries respect each other’s territorial integrity. This phrase is used routinely by Morocco in relation to its occupation of Western Sahara (including to imprison critics of the occupation) and its use here can be read unambiguously as code for UK endorsement of the occupation.

Such an endorsement is bad for the UK’s international reputation. Supporting an illegal military occupation in exchange for some business opportunities associated with a sporting event is a bad look. For the British government to do this when it is vigorously (and rightly) championing Ukraine’s right to self-determination and taking a more sympathetic stance towards the plight of the Palestinians (albeit only when the alternative is effectively endorsing a genocide), looks hypocritical. Such political hypocrisy may not be surprising, but it provides further ammunition to those hostile to the UK, and to Western liberal democracy at large, who would argue that we are not to be trusted or taken seriously when we champion an international rules-based system. The UK is signalling that it is willing to accept and endorse the taking of territory by force if the price is right and the victims of occupation are deemed sufficiently insignificant.

Endorsing a plan that isn’t a plan

The communiqué states that the UK considers Morocco’s autonomy plan to be “the most credible, viable and pragmatic basis for a lasting resolution of the dispute” in Western Sahara and that both signatories believe that “with goodwill on all sides, a solution could be found very soon.” The BCC also cites British diplomats as saying that the new agreement requires “a new commitment from Morocco to support the principle of self-determination, publish a new version of its autonomy plan and restart negotiations.”

Given the history of the conflict, this all seems incredibly optimistic, and should be interpreted either as extremely naïve or simply disingenuous. The UN has been organising negotiations between Morocco and the Polisario since the 1991 ceasefire, without progress towards resolving the conflict. The promised referendum on self-determination has never materialised, with key sticking points being disputes over who should be eligible to vote and Morocco’s refusal to accept any vote in which Western Saharan independence is an option. It is difficult to see how the right to self-determination can be exercised under such a constraint.

Most observers view the autonomy plan as a fig leaf for the occupation, intended to present the appearance of constructive engagement while allowing Morocco to further consolidate its control of Western Sahara. The autonomy plan is a unilateral solution imposed by one party to the conflict. Any resolution of this conflict needs to secure the consent of both parties – Morocco and the Polisario. The letter from the Moroccan representative to the UN that proposed the autonomy plan in 2007 contains no mention of the Polisario, and the plan appears to contain no mechanisms for engaging with the them.9 Consequently, it is not a credible vehicle for negotiating and end to the conflict and is at best a proposal for how occupied Western Sahara will be governed.

The idea that Morocco will significantly shift its position as a result of a new strategic dialogue with the UK, when the latter has already endorsed the autonomy plan in exchange for economic gain, seems rather laughable. Morocco is adept at using whatever levers it has at its disposal to bribe and blackmail foreign governments into recognising its authority over Western Sahara, and this case will be no different. The British government is simply handing Rabat leverage over its foreign policy in the Maghreb. One can only presume that the smart, well-educated people at the FCDO know all this, and that the UK government is playing along with Morocco’s pretence that it is sincere about finding a just and durable solution the conflict.

Ignoring partition

The autonomy plan includes no mechanisms for addressing the status of the areas of Western Sahara that are controlled by the Polisario, referred to by the Sahrawis as the Liberated Territories. These lie to the east and south of a 2700 km long series of earthworks, forts, fences and minefields exploiting the natural topography, which constitute the Moroccan defensive ‘wall’ or Berm. The Berm was constructed by Morocco during the 1975-1991 conflict to progressively annex territory as it was brought under Moroccan control. Today, the Berm represents a line of partition of Western Sahara, and is even shown (wrongly) as an international border on many modern maps.

Throughout the 2010s, parts of the Liberated Territories to the east and south of the Berm were settled by Sahrawi civilians who moved there from the camps (in 2020 it was estimated that some 60,000 people had settled in these areas10). This settlement process ended after the breakdown of the ceasefire in November 2020, following Donald Trump’s recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, an incursion by the Moroccan military into a prohibited buffer zone to the east of the Berm in response to Sahrawi protests, and the resumption of military action by the Polisario in response.

Today, existence in the Liberated Territories is difficult due to the routine targeting of traffic – both military and civilian – by Moroccan drones. It is difficult to square this with the communiqué’s advocating of “the non-use of force for the settlement of conflicts.” Despite the risks from drone strikes, the Polisario military maintains a significant presence in the Liberated Territories, which contain a number of military bases from which the Sahrawi armed forces launch regular attacks against Moroccan positions along the Berm.

Morocco has consistently ignored or denied the existence of the Liberated Territories, deliberately conflating the large areas under Polisario control with the 5km wide demilitarised ‘buffer strip’ immediately east of the Berm, established under the terms of the 1991 ceasefire. Any Moroccan acknowledgement of the partition of Western Sahara would represent an admission that it does not control the entire territory and would raise questions about the current and future status of those areas outside its control. The Moroccan government’s approach is apparently to simply not talk about the Berm or the areas to its east, and to pretend that neither exists. Soon after the autonomy plan was proposed (in 2007), I attended the launch of a book written to promote it, written by a Moroccan academic. When I asked the author what the autonomy plan proposed for the areas under Polisario control east of the Berm, he told me that the existence of these areas was a fabrication by the Polisario, who had never retaken, and did not control, any parts of Western Sahara. When I told him that I had spent several years working in these areas with Sahrawi colleagues and representatives of the Polisario, he made a hasty exit, returning with embassy staff to berate me for my criticism of Morocco’s occupation.11

Excluding refugees

Yet another major problem with the autonomy plan is its failure to address the plight of the refugees in Algeria. The plan purports to guarantee “all Sahrawis, inside as well as outside the territory [of Western Sahara], that they will hold a privileged position and play a leading role in the bodies and institutions of the region, without discrimination or exclusion.”9 However, it is difficult to see how this promise can be realised, for a number of reasons.

Regarding the Sahrawis “outside the territory”, Morocco has repeatedly insisted that the numbers in the camps are much lower than those cited by international organisations and indicated the 2018 census. Morocco has also claimed that most of the refugees are not Sahrawis but migrants from the Sahel.12 It is difficult to guarantee any rights or privileged position to people whose existence you deny.

Morocco’s brutal treatment of pro-independence activists in the occupied territories, including beatings, arbitrary detention, house arrest, sexual assault and disappearances, suggests that any refugees who did return would not find a warm welcome.13 14 The communiqué’s promise to “uphold the principles, of peace, security, tolerance, and human rights” rings rather hollow against this background. Notably, the peacekeeping force in Western Sahara is one of the few such forces without a mandate to monitor human rights abuses.15

In addition, Sahrawis outside of the Occupied Territories are already represented by the Polisario, as recognised by numerous international institutions including the UN, the European Court of Justice (see above), the African Union, and dozens of countries that have formally recognised the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). The SADR is a small but fully functioning state, with all the normal apparatus of government.

The inclusion of “all Sahrawis” in the governance of an autonomous Saharan region within a greater Morocco must, by definition, extend to the Sahrawis in the refugee camps and – critically – to their existing political representatives. The unilateral nature of the autonomy plan and its rejection by the Polisario makes it unfit for the purpose of resolving the conflict. A version of the plan that allows for the return of some 200,000 independence-minded refugees who have spent half a century viewing the Moroccan state as their enemy seems unlikely. A version of it that allows them to be represented by their established and widely recognised government seems even more so.

Endorsing failure and insecurity

Any meaningful plan to end the conflict must be predicated on a new ceasefire and new negotiations between Morocco and the Polisario, without preconditions. In the absence of these, the autonomy plan can only be implemented unilaterally by Morocco in the areas of Western Sahara that it occupies. This would leave a de facto Sahrawi territorial state in the Liberated Territories and the refugee camps. For this to represent a durable solution to the conflict, Morocco and the Polisario would need to agree a formal partition plan for the territory, with the Berm acting as a new international border (as it is already represented, inaccurately, on many online maps, including those published by national governments and multilateral organisations). Whether either party is prepared to negotiate such a settlement is highly uncertain, given both Morocco’s and Polisario’s claim to the entire territory, with international law supporting the latter while the former is endorsed by a small but growing number of national governments that now includes the UK.

In the absence of a formal partition agreement or one of the parties to the conflict relinquishing its claim to Western Sahara, there are three possible scenarios, none of which represents a satisfactory resolution to the conflict.

In Scenario 1, the endorsement of the autonomy plan by Morocco’s supporters and its implementation by Rabat makes little or no material difference to the situation on the ground. In this scenario hostilities, whether diplomatic or military, continue, and the nature of the conflict remains unchanged. The majority of Sahrawis are forced to remain refugees, and the occupation of Western Sahara west of the Berm continues as usual. It is difficult to see what would change on the ground as a result of international endorsement of the autonomy plan. This is arguably the most likely outcome in the near-term.

In Scenario 2, there is a de facto acceptance of partition by both sides and the international community, and the Liberated Territories eventually constitute a reduced Sahrawi territorial state, with this situation normalising over time. The SADR seeks to become a UN member state and gains wider diplomatic recognition. This is essentially the situation pertaining prior to the resumption of hostilities in November 2020. However, without any formal agreement to partition Western Sahara along the line of the Berm, the peace would be fragile, as the events of recent years have demonstrated. The limited resources available in the Liberated Territories would pose severe challenges to any programme of resettlement from the camps, and any resumption of hostilities would have a devastating effect on a resettled Sahrawi population. UN membership and the wider normalisation of diplomatic relations would depend to an extent on Morocco’s willingness to accept a Sahrawi state in the Liberated Territories.

In Scenario 3, which is much more troubling, acceptance of Morocco’s autonomy plan is taken as a green light by the Moroccan state to complete its occupation of Western Sahara. Moroccan troops cross the Berm into the Liberated territories, resulting in a ground conflict between the Moroccan and Sahrawi armed forces that could be protracted. Any such conflict would inevitably draw in Algeria, potentially igniting a wider regional conflict. Spillover from this conflict would negatively impact security in the Sahara and Sahel, via the transfer of weapons and opportunities for militant Islamic groups to exploit the situation for their own political ends.

None of the above scenarios represent a satisfactory resolution to the Western Sahara conflict. None of them move the Maghreb towards the much-touted regional economic integration that is held out by Morocco and its supporters as the logical outcome of such a resolution.

A just and lasting end to the conflict requires a settlement that is acceptable to both Morocco and the Polisario. Ideally, this would involve self-determination for the Sahrawi people through the UN mandated referendum and the full decolonisation of Western Sahara. The UK’s endorsement of Morocco’s autonomy plan, developed to avoid just such an outcome, will only make such a settlement less likely.

Even if self-determination, decolonisation and adherence to the principles of international law are deemed hopelessly optimistic (as, presumably, they are by the UK government and the FCDO), a lasting peace in Western Sahara still requires the agreement of both parties to the conflict. There can be no durable resolution to the conflict without the agreement of the Polisario and the consent of the Sahrawis they represent. These parties are excluded by the autonomy plan in its current form. Endorsement of the plan by countries such as the UK serves only to legitimise Morocco’s occupation and alienate and marginalise the Sahrawis further.

This will do nothing for regional peace and stability. One of the explanations I heard for Polisario’s resumption of military action in November 2020 was that the Sahrawis in the camps would have accepted nothing less. This feeling is strongest amount younger Sahrawis who see nothing in their future except lives as permanent refugees with no prospects. Every endorsement of the Moroccan occupation by a foreign government, whether the United States in 2020 or the UK in 2025 amplifies the the Sahrawi’s feelings of hopelessness. Abandoned and forgotten by the world, they feel they have nothing to lose, and everything to gain by putting the fight for their homeland back in the spotlight.

For decades, the Polisario Front has expertly managed the frustrations of its people, pursuing diplomatic routes to end the conflict and eschewing acts of political violence. This is one reason the Western Sahara conflict is much less well-known than other, similar conflicts. This approach has been remarkably successful in building social cohesion and political stability, and in keeping the spectre of violent jihadism at bay. However, some Sahrawis have slipped through the net, joining and in some cases leading Islamic militant groups in the Sahel. The more hopeless their situation becomes, the greater the appeal of such groups is likely to be.

The British government’s betrayal of the Sahrawi people in exchange for some putative business contracts to support a football tournament is short-sighted as well as immoral. Lammy’s transactional fawning over the public relations stunt that is Morocco’s Saharan autonomy plan will make a durable solution to the Western Sahara conflict less, not more, likely. Any such solution must involve, and be acceptable to, both parties to the conflict. Endorsing a unilateral ‘solution’ proposed by one party, that intentionally excludes the other, is unfathomably stupid from a security perspective. Instead, the British government should be putting pressure on Morocco to make a genuine accommodation with the Polisario to find a lasting solution to the conflict.

Of course, Lammy’s intention is not to support long-term political security and economic integration in the Maghreb, but to generate some positive headlines, suck up to business, and please potential political donors, at a time when his party appears to be constantly on the back foot. He is quite prepared to throw an entire population under the wheels of a military occupation to achieve these narrow, self-serving outcomes. To witness this behaviour from a nominally socialist party whose leader is a former human rights lawyer, a party originally established to protect the rights of working people and give a voice to the downtrodden, marginalised and vulnerable, is truly disheartening.

- A 2018 census estimated the population of the camps at over 173,000, and a 2020 appeal for COVID support estimated that 60,000 Sahrawis lived in the areas of Western Sahara under Sahrawi control. This population has moved to the camps and norther Mauritania since November 2020 as a result of the resumption of armed hostilities. Sources: (i) Sahrawi Refugees in Tindouf, Algeria: Total In‐Camp Population, Official Report, UNHCR, March 2018. Available via https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-8-2018-002896_EN.html and https://www.acaps.org/country/algeria/crisis/sahrawi-refugees, (ii) Urgent Appeal: Effects of COVID-19 on the humanitarian situation of the Sahrawi refugees. Sahrawi Red Crescent, 28th April 2020.

︎

︎ - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c5yxkzdq11zo.

︎

︎ - https://plmr.co.uk/2025/01/growth-at-all-costs-labours-climate-commitments-might-just-be-the-price/

︎

︎ - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c8ed6e4l29lo

︎

︎ - ttps://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jun/05/labour-using-brexit-to-weaken-nature-laws-mps-say

︎

︎ - https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jun/03/revealed-5000-english-nature-sites-at-risk-under-labours-planning-proposals

︎

︎ - Formally known as the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara and referred to using its French acronym, MINURSO: https://minurso.unmissions.org/. which has operated in Western Sahara since 1991, when the UN brokered a ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario Front, the Sahrawi national liberation movement. Spoiler alert here – the referendum has never taken place.

︎

︎ - Described in Press Release 170/24 from the European Court of Justice, dated 4 October 2024, which also contains links to the original text of the rulings. See alos Press Release 166/21 relating to the 2021 ruling.

︎

︎ - Letter dated 11 April 2007 from the Permanent Representative of Morocco to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/597424?v=pdf

︎

︎ - Urgent Appeal: Effects of COVID-19 on the humanitarian situation of the Sahrawi refugees. Sahrawi Red Crescent, 28the April 2020.

︎

︎ - You can read me account of the launch on my old Sand and Dust blog here.

︎

︎ - These were common talking points in online discussions I had with Moroccan apologists and representatives throughout the 2000s and 2010s, including those purporting to represent CORCAS, the Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs.

︎

︎ - https://www.amnesty.org.uk/urgent-actions/sahrawi-activist-risk-further-assault

︎

︎ - https://www.hrw.org/sitesearch?search=western+sahara

︎

︎ - https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/MDE2932352020ENGLISH.pdf

︎

︎

As someone who has worked on climate change for almost three decades, starting with the physical science and moving onto adaptation, I’m firmly with the majority of those polled in the above survey. This is the result of over twenty years of interaction with those responsible for the development and implementation of climate policies at the global, national and local levels.

The Guardian poll arrived just as I was questioning the value of much my consultancy work, which to a large extent has been targeted at decision-makers involved in financing, designing and implementing adaptation and resilience interventions. This article contains my reflections on what I see as our continuing failure to take meaningful action on climate change, whether in the form of mitigation to reduce or remove carbon emissions, or adaptation to the unavoidable impacts of the climate change to which we have already committed ourselves. It ends with some thoughts about what aspects of my work have the least and most value in terms of meaningful impact, and what this means in terms of the type of work I do and don’t want to pursue in the future.

One thing that is very clear to me is that some of the decision makers I have encountered in my two decades of consultancy work understand the magnitude of our climate predicament, while others do not. However, all have their capacity for action constrained by the systems and paradigms within which they are compelled to operate.

The horizons of most governments are overwhelmingly short-term, and the nature of power means that the imperative of politics at all levels tends to be the maintenance of the status quo, at least insofar as it protects and amplifies existing patterns of privilege. While often well-intentioned, civil servants are subordinate to the priorities of the governments they serve, with limited scope for innovation. I will repeat my anecdote about the representative of the UK Treasury (our ministry of finance) who told me in 2002 that “we can probably do 550, but 450 isn’t realistic.” This was in relation to government support for a limit on atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations measured in parts per million (ppm). 450ppm will take us to somewhere around 2°C of warming above pre-industrial levels (at the time of writing, in June 2024, we’re at around 427ppm); 550ppm is likely to result in what most scientists believe will be an utterly catastrophic warming of 3°C. This is around half the difference between an ice age and a warm interglacial, but occurring some fifty times faster. Such a change will radically alter the distribution and availability of key resources, make some regions physically or functionally uninhabitable, and result in all sorts of social, economic, political and demographic dislocations, the precise nature of which we can only speculate about.

Nonetheless, as the gentleman from the Treasury illustrated, these concerns are secondary to those relating to short-term economic growth and what is politically expedient. The maintenance of the status quo in the near term is more important to governments than a stable climate, even if this means upending the world as we know it in the medium to long term. (To politicians in countries with a modicum of democracy, or the appearance thereof, medium to long term simply means a handful of electoral cycles into the future.)

At the global level, the multilateral organisations and funds tasked with tackling climate change are similarly constrained. Largely dependent on official development assistance (ODA) provided by national governments, their activities tend to reflect the priorities of their donors. These range from the noble, such as reducing poverty and improving conditions for women, girls and children, to the more ideological (e.g. support for the private sector and free trade), and the downright cynical (e.g. reducing migration flows to rich countries and creating opportunities for those same countries’ businesses). The quantities of ODA channelled into climate finance are dwarfed by the subsidies granted to fossil fuels by the same donor governments. Consequently, for all the excitement about the pace with which new renewable energy capacity is growing, renewables have simply added capacity to a global energy sector otherwise based on continually expanding fossil fuel use. To add insult to injury, donor nations consistently fail to provide the money they have pledged to help poorer countries pursue cleaner development and adapt to the impacts of unavoidable climate change caused largely by the emissions of rich countries. We are certainly making progress in transitioning to renewables, and by some measures this is rapid. But it is painfully slow and incremental compared to what is needed to deliver on the temperature goals agreed by the world’s governments under the Paris Agreement.

Things are arguably even worse when it comes to adaptation. Long the poor cousin of mitigation, even the money that has been spent on adaptation appears to have done little good, and much has probably been counterproductive. A 2021 paper to which I contributed listed a host of reasons why adaptation interventions often increase vulnerability and risk. Adaptation is often based on top-down, technocratic approaches that pay insufficient attention to local contexts, which can undermine more community-driven responses and entrench existing power relations through elite capture of adaptation resources. Project-based approaches and insufficient engagement of local stakeholders often means that adaptation actions are not sustained once project funding ends. A focus on the short-term and a failure to consider future conditions can result in temporary solutions that increase risks in the medium to long term – what we call maladaptation. Another paper reviewed adaptation responses across 39 countries and concluded that 41% of responses exhibited maladaptive characteristics.

My own experience of working on adaptation and resilience interventions is that they are often little more than rebranded exercises in conventional economic development, that pay little or no attention to potential future (and sometimes even current) climate risks. Largely designed by external actors and framed by the priorities of donors, they often achieve little, with any actual or potential benefits evaporating at the end of the project lifetime. Of course, there are exceptions, but even there it is difficult to assess the sustainability of any adaptation or resilience benefits. Assessment of adaptation interventions tends to focus on metrics such as the number of people supported and other narrow output-based measures. Little attention is paid to the extent to which adaptation actions actually reduce climate-related risks, or how they might help people navigate future climate change impacts.

I often feel that a lot of my work on adaptation – particularly on adaptation monitoring, evaluation and learning – is really just an exercise in bureaucratising responses to existential risks. In fact, so much of our activity around climate change appears to be little more than ‘busy work’ intended to give the impression (to others but also to ourselves) that we are actually doing something to address the problem, when in reality we are not.

This situation is echoed in the private sector. Positivity and enthusiastic optimism is mandatory in the business world, as any glance at LinkedIn will demonstrate. When it comes to climate change, there is an abundance of established companies and startups promising radical, innovative (and mostly technological) solutions to address climate change. Some of these are genuinely helpful, for example in increasing the efficiency of resource use and thus in reducing emissions, energy and water consumption, and the application of pesticides and fertilisers, relative to a business-as-usual baseline. Other enterprises provide employment and income to people whose livelihoods and food security are otherwise being undermined by climate change. However, there are plenty of firms selling dubious carbon offset schemes (some of which damage the environment, result in exclusion and dislocation, and even support military occupation), opportunistically exploiting clients’ appetites for greenwashing, and driving ostensibly green but resource-intensive consumption. Recently, I have been working with a client to support adaptation and resilience startups, and some of these do appear to offer genuine adaptation and resilience benefits. However, many are more concerned with general sustainability and improvements in productivity, and the links with adaptation are tenuous at best.

While business has a role to play in tackling the climate emergency, the solution to the crisis won’t be found in the private sector. Business cannot deliver the emissions reductions we need on a sufficiently short timescale – unless, of course, we are talking about fossil fuel companies, who have demonstrated repeatedly that they are bad actors. When it comes to adaptation, which is highly context-specific, the private sector no doubt has a role to play in supporting resilience to climate change and its impacts, but I doubt it can do much to help us address large, and in some cases existential, risks. Some of the risks we face are so great that responses to them will need to be coordinated on a large scale through mechanisms that cannot be provided by the market, or by individual billionaire philanthropists.

Those who fund, design and implement actions intended to address climate change love to talk about innovation and transformation. The UK has even developed a key performance indicator to measure the transformational impacts of its international climate finance. However, evidence of actual transformation is extremely limited, and where it exists it is restricted to very specific contexts. In the end, the metrics that matter are annual global emissions, atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, variables that tell us about the behaviour of the climate system, and measures of loss and damage associated with climate change impacts. And these are all rapidly going in the wrong direction.

It seems we are incapable of moving away from business-as-usual, even in the face of existential threats to the the systems on which we depend for our survival and wellbeing, not to mention direct threats to human lives. One of the transformational changes those of us working at the science-policy interface have long advocated is the integration or mainstreaming of climate change considerations into policy and planning. It seems that this was naive. Rather than resulting in systems that genuinely address climate change drivers and risks, this mainstreaming has instead resulted in mitigation and adaptation being co-opted into business-as-usual. At best, this means that transitions to low-carbon, resilient societies and economies are painfully incremental; at worst it means that lip service to adaptation and mitigation is used to justify practices that are unsustainable or maladaptive.

We all know radical change is hard, and perhaps it really can only happen in response to a crisis, to grudgingly quote Milton Friedman. Certainly, many (myself included) would argue that we are in a crisis. Perhaps the perception of crisis has simply not reached those with the power to drive change, or perhaps they are too busy responding to other crises – real or imagined – that they deem more important. Perhaps they lack the imagination to appreciate what a trajectory to 3°C of warming might look like, or perhaps they do not care. In reality, a host of factors are at work to drive ‘climate inaction’ and ‘non-decision making’ among senior decision-makers in government and business, as explored in this great paper by Lauren Rickards and her colleagues. A lot of this boils down to institutional cultures and the fact that decision-makers are insulated from climate change impacts and the consequences of their (in)actions.

Many of the rest of us are not so insulated from the effects of climate change, or distanced from the consequences of decision-makers’ actions. No wonder that so many of us are experiencing what has come to be known as climate anxiety. For some, anxiety has metastasised into despair. One survey of 10,000 young people across 10 countries found that three quarters of respondents think the future is frightening, and over half believe humanity is doomed. Some people believe that the twin climate and ecological crises will drive humans to extinction, or that they or their children will die as a result of climate change. These responses often come from people in wealthy countries who are much better placed to cope with climate change impacts than those in poorer parts of the world, whose physical exposure to dangerous impacts is significantly greater.

Those of us working on climate change find ourselves caught between the inaction of governments, the often irrational optimism of the private sector, and the despair of the general public. Some of us remain optimistic and determined, but I’ll stick my neck out and propose that these people are probably in the minority, and most of us feel a profound sense of frustration that is amplified by the intensifying urgency of the situation. Those of us who engage with decision-makers on a regular basis have to balance the pragmatic realities of what can be achieved in the narrow operating space allowed by the status quo, and the knowledge that operating within this space will probably achieve very little. Worse, it risks legitimising systems and approaches that are driving the twin climate and ecological crises, and maintaining the structural inequalities that lead to so much climate (and general) injustice. Some of us enjoy the proximity to power and the resulting sense of agency that such work can bring, and this may be sufficient compensation. But I hear of some colleagues who, having been thus seduced, have become extremely bitter that their efforts to drive change ultimately have amounted to little or nothing. In short, they have been used to legitimise the systems and structures that are driving the problem they originally set out to address. Those systems and structures have squeezed them dry with what, it transpires, was just more busy work.

In my several decades working in the adaptation and resilience space, as both a consultant and researcher, I’ve learned a lot, published a fair amount, and have even been described as a ‘thought leader’ by some of my more generous colleagues. But I can’t honestly say that I think I’ve made any difference, or that my work has influenced climate change policy or practice in any meaningful way. I’ve certainly influenced the way people think, talk and write about adaptation and resilience, but again, I’m not sure this has been translated into better responses.

In some ways I have been extraordinarily fortunate, in that work has always come to me without my having to chase it. To a large extent, this has been the result of my setting myself up as an adaptation consultant when such creatures were vanishingly rare, and having good networks through which I’ve secured work through reputation and word-of-mouth (I also owe a lot to my friend and colleague Bo Lim, sadly no longer with us, who gave me my first consultancy break working with her new adaptation group at UNDP in 2005). However, this has meant that I have been less strategic than I might have been, often (although not always) taking work because it is there, rather than because I think it is particularly useful. Of course, the need to make a living means that one cannot always be too selective, and this approach has meant I haven’t sacrificed months or years of my life frantically writing bids and proposals that are often unsuccessful, as have many of my colleagues. But this approach comes with its own costs, chief among which is the frustration of working on assignments that often seem to achieve little, even if they do run to completion (I’ve worked on a number of programmes that do not, often as a result of shifting political priorities, changes in funding regimes, unrealistic expectations, or insufficient engagement with key stakeholders).

So, the question in my mind is, how to proceed? What can I take from my own learning to increase the positive impact of my work? What should I be doing less of, and what should I be doing more of? Starting with the former, from now on, I will be looking to avoid the following:

- Initiatives that claim to support adaptation and build resilience, but pay only vague lip-service to these concepts and lack well thought out frameworks for understanding and addressing evolving climate risks. Such initiatives are endemic, particularly in global development contexts. They can confer some resilience to existing climate variability, and may enhance resilience to climate change to some extent. However, this is often more by accident than design, and they can just as easily result in maladaptation.

- Interventions that are branded as adaptation or resilience simply as a means of attracting climate finance or related funding. These overlap heavily with the previous category, and are extremely common. This is an understandable strategy for those genuinely concerned with delivering urgently needed development, and may result in positive outcomes. Such initiatives may also offer opportunities to address resilience and adaptation, but the benefits tend to be marginal at best.

- Top-down, technocratic, funder-driven interventions that do not adequately engage the people whose adaptation and resilience they set out to support. Too many initiatives end up like this, even if they are conceived with meaningful participation in mind, and it is important to look out for early warning signs that participation will be limited in extent (i.e. who is engaged) or scope (the degree of ownership over the intervention by ‘beneficiaries’ and the degree to which they influence planning, design and implementation).

- Initiatives pursuing solely incremental approaches based on the assumption that adaptation is simply about protecting and preserving existing systems and practices. While such approaches have their place, many such systems and practices may be unsustainable under future conditions, meaning that adaptation is about finding alternatives.

- Monitoring and evaluation exercises that do not go beyond the measurement of short-term output indicators, and that do not address the actual or likely effectiveness of adaptation and resilience actions in addressing climate change risks and impacts.

- Evaluations and learning assignments for organisations that do not have any demonstrable mechanisms for capturing, disseminating and using learning. These assignments are time and resource intensive, often take longer than the time allocated by the client, and tend to result in lengthy reports that few people read. Valuable learning is often ignored and lost, does not inform future work, and the same mistakes are repeated.

There are other, obvious traps to avoid, including supporting blatant greenwashing and initiatives that clearly amplify climate injustice, for example by displacing or excluding vulnerable groups. Thankfully, I have found it easy to avoid these from the start. But the other lessons detailed above were learned the hard way.

Now that I’ve got the negativity out of the way, here is what I am looking to do more of:

- Working with clients who genuinely want to support and pursue ambitious but pragmatic adaptation, rather than business-as-usual with a vague adaptation or resilience spin.

- Helping people and organisations understand the relationship between resilience and adaptation, and the often bewildering array of related terms and concepts, so that they can develop frameworks and systems for building their own resilience and pursuing their own adaptation actions.

- Supporting organisations with scenario planning informed, but not driven, by climate information including climate projections. This involves asking ‘what if’ questions to encourage people and organisations to think about what actions are desirable and feasible in response to specific future climate change outcomes.

- Looking at how adaptation governance can be improved to make action (and finance) more sustainable, effective, and transparent, through more local ownership of adaptation processes.

- Working at the local level to empower communities and organisations (including local authorities) to understand climate change and related risks and lay the groundwork for future adaptation. While national policies influence the contexts in which adaptation occurs, people feel the impacts of climate change at the local scale.

- Working on transformational adaptation and how we do it, for example through phased adaptation that moves from incremental to transformational approaches as novel alternatives to existing systems and behaviours are piloted and introduced in response to evolving climatic, environmental and related conditions.

- Supporting clients to develop ways of assessing the effectiveness of adaptation, using a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. This requires a clear understanding of what successful adaptation looks like to those who are pursuing it – something that is surprisingly lacking in many contexts.

- Working with people and organisations to develop resilience mechanisms to prepare for large and potentially sudden climate disruptions and their direct and indirect impacts. These may include severe disruptions to global supply chains on which we are heavily dependent for our food security and economic wellbeing, climate hazards such as unprecedented extreme heat, and a possible pronounced regional cooling associated with the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

The above lists (both negative and positive) are not exhaustive, but provide a reasonable guide to the direction in which I want to take my work in the future. Put simply, I want to pivot away from ‘busy work’ that does little more than legitimise a failing status quo while delivering some limited resilience benefits at best, to work that encourages and supports bold and ambitious but pragmatic adaptation that prepares us for the profound changes that are on their way. If any of this strikes a chord, or if you want to work with me on the basis of what I have written here, then get in touch.

]]>I first read the Dune novels as a teenager in the early 1980s, in time to be excited at the prospect of David Lynch’s flawed 1984 adaptation. I was more excited at the prospect of Villeneuve’s two-part adaptation of the first novel, the second part of which screened recently to wild and (I think) justified acclaim. Despite some significant deviations from the book and some contentious issues around representation, both films capture much of the essence of this story that had such a profound affect on my much younger self. In a recent interview following the release of Dune Part 2, Villeneuve and score composer Hans Zimmer talked about reading Dune in their teens, and reacting in a way that is strikingly familiar to me.

For me, one of the joys of Dune and its sequels has been that every reading is profoundly different from the last. Having read the novels at different stages of my life, I’ve seen them through multiple different lenses shaped by my experience and knowledge of the real world, or indeed lack thereof. To a teenager navigating the challenges of adolescence, the book was as much a guide as anything else, an encouragement to persist in the face of adversity, to generally improve oneself. Who wouldn’t want to be more like Paul Atreides (at least before he goes full messiah), or the Bene Gesserit, with their ostensibly near omniscient view of human society and almost supernatural physical abilities (their somewhat eugenicist programme of selective human breeding notwithstanding). What young man wouldn’t want the martial skills of Gurney Halleck or (definitely my favourite) Duncan Idaho? And which die-hard Dune fan has never tried out the Litany Against Fear in a difficult moment?

Of course, teenage me missed a lot of the nuance of the stories and took too much at face value. Herbet’s often rather right wing, individualist, libertarian politics were deeply seductive to fourteen year-old me as I began to question the established social and political order. As a precocious kid discovering his own agency on the cusp of adulthood, I fell into the same trap as many adolescent white boys, identifying with the young Paul Atreides and missing the extent to which Herbert’s aim was to subvert and challenge the conventional hero (and indeed ‘white saviour’) narrative, and to offer a critique of power. Whatever you think of Herbert’s politics, bold assertions, and skill as a writer, many of his observations are evergreen, and some seem even more pertinent today. After fourteen years under a government that has made blatant the kelptocratic nature of British politics and the existence of a thriving hereditary ruling class that most of us had assumed was all but extinct, Herbert’s observation that democracies inevitably evolve into oligarchies seems rather on the nose. As that same system has elevated those who are least competent and self-aware, and in many cases somewhat sociopathic, we are reminded of Herbert’s assertion that power attracts people who are easily corrupted, who “want power for the sake of power,” a significant proportion of whom are imbalanced or “in a word, insane,” Clearly, these observations have wider global relevance. The Dune series has many layers, and is far from being simplistic libertarian propaganda. I will remain eternally grateful that it was the works of Frank Herbert and not, say, Ayn Rand that shaped me in those impressionable years.

Dune’s deep Islamic infuences largely went over my head on the first reading, although even to my culturally and historically ignorant mind they still hugely enriched the worldbuilding. I paid more attention to them when I spent some time in Egypt, Jordan and Syria in my 20s, started to learn a bit of Arabic, and took to reading about the history of the region and the rise of Islam. I remembered Herbert’s use of terms such as Mahdi, alam al-mithal, Lisan al-Gaib, and Jihad (the western obsession with ‘jihadis’ wasn’t really a thing then), and the Bene Gesserits’ favourite exclamation of Kull Wahad! My curiousity was sufficiently piqued to prompt me into a second reading of the Dune series, a decade after the first.

My Arabic dictionary wasn’t much help in deciphering Herbert’s loan words. This was probably due, at least in part, to my inability to move beyond poor attempts at literal interpretation. It also seemed that Herbert was doing his own thing with some of these terms, and perhaps drawing inspiration from other languages related to Arabic in which meanings were different. Recently, I’ve developed a better understanding of how Arabic and other languages are deployed in Dune, and of the extent to which Herbert drew on Islamic and other history and culture, through the excellent work of Haris Durani and other scholars of Dune’s representation of Islam. My delight on discovering that such people exist is difficult to articulate, and their articles are a must-read for anyone interested in these aspects of the story – aspects that have been, if not erased, then at least radically toned down in the films. Durani’s criticism that the first of Villeneuve’s Dune films erased the muslimness of Dune echoed my own reaction. If this jarred to me as a non-muslim, how must it have looked to the many muslim fans of the books? To me, the second film seemed to be less problematic in this regard, but I await the responses of those better qualified to judge.

My third reading of the novels was, once again, prompted by travel. By this time I was in my thirties. After completing my PhD (on linking ecological change and climate change in the Sahel and Sahara – very Dune), I took up a postdoc position that involved fieldwork in the central Sahara, in the Fezzan region of southern Libya. The remit was to identify archaeological and palaeoenvironmental sites that could tell us about past human-environment interactions, using a combination of remote sensing and field surveys. This involved a lot of roaming around the desert navigating treacherous sand seas. It seemed like an obvious context for another reading of Dune. This time, my focus was on the environmental aspects of the story, from the politics of resource extraction to the transformations of the planet Arrakis across the six books of the series, which echo the successive arid and humid phases that have shaped the Sahara. As well as an exploration of political and religious themes and a critique of heroes, Dune is also an ecological thriller, and a meditation on our domination of nature (and yes, it includes a plausible mechanism for a desert planet almost devoid of vegetation to actually have an oxygen-rich atmosphere). Herbert developed an interest in ecology as a journalist covering attempts to stabilise mobile dunefields in Oregon, and this struggle between humans and a dynamic nature is echoed in his books.

Following my fieldwork in Libya, I found myself organising thematically similar work in Western Sahara, a non-self-governing territory bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Morocco to the north, Algeria to the east, and Mauritania to the east and south. I didn’t think too much about Dune while I was working in Western Sahara, between 2002 and 2009, or subsequently, as I continued to work with the Sahrawi government on issues related to contemporary climate change. I probably thought three readings was enough. But Villenueve’s films have prompted a fourth reading, this time with a focus on how the story links resource extraction with colonialism and anti-colonial struggles. And now I can’t think about Dune – books or films – without thinking about Western Sahara and the struggles of my Sahrawi friends and colleagues against modern day colonialism. Partly this is because of a soundscape that, in certain scenes, captures the crisp silence of the desert just as a smell can encapsulate a formative experience from childhood, transporting me right back to the Sahara. But mostly it is a result of the striking parallels between the struggle of the fictional Fremen and that of the Sahrawis.

In Dune, Herbert drew significant inspiration from anti-colonial liberation struggles, apparently taking the Fremen rallying cry of ya hya chouhada from the Algerian war of independence. This is translated in the book as ‘long live the fighters’, but more accurately translates as ‘long live the martyrs’. It reminds me of graffiti daubed above a rockshelter in the remote southeastern region of Western Sahara, which reads (using a similar transliteration to that used above) kull al-watan aw chouhadanan – all the homeland or martyrdom. This refers to the nearly five decades of struggle by the Sahrawis against the occupation of their land by Morocco, which makes Western Sahara ‘the last colony in Africa.’

With the death of Spanish dictator General Franco in 1975, Spain yielded Western Sahara (previously Spanish Sahara) to Morocco, which claimed the territory as its ‘Southern Provinces.’ However, the native Sahrawis – a historically nomadic people descended from a mixture of Arab and Berber tribes, the former believed to have originated in Yemen – had other ideas, namely of independence. The Sahrawi liberation movement, the Polisario Front, and its Sahrawi Popular Liberation Army (SPLA), fought Morocco from 1975 until 1991, turning their intimate knowledge of the desert against the Moroccan invaders through guerilla warfare, as do the Fremen in Herbert’s Dune. This conflict resulted in the displacement of tens of thousands of Sahrawis to refugee camps in Algeria, which today house somewhere in the region of 200,000 exiled Sahrawis and serve as the seat of government of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), The SADR has been recognised by some 80 countries over the course of its existence, and is a member of the African Union.

In 1991, the United Nations brokered a ceasefire and promised a referendum (spoiler: the referendum never happened). By this point, Morocco had occupied some three quarters of Western Sahara, which it protected from SPLA attacks with a 1700km series of defensive earthworks, fences, minefields and forts, manned by up to 150,000 military personnel according to some estimates. This ‘Wall’ or ‘Berm’ as it is variously known, echoing the shield wall that protects the fictional Harkonnen colonisers from both the desert climate and the Fremen in Dune, effectively partitions Western Sahara into the Moroccan controlled Occupied Territories and the Sarhrawi controlled or Liberated Territories. Until 2020, the latter were home to a growing number of Sahrawi civilians from the camps, with the main settlement of Tifariti acting as a de facto capital of the physically diminished Sahrawi territorial state. This settlement of the Liberated Territories ended in November 2020, when Morocco broke the ceasefire agreement by sending its troops into the 5km demilitarised buffer strip that runs along the Sahrawi controlled side of the Berm, to break up Sahrawi protests against the export of raw materials from the Occupied Territories through the Berm, to Mauritania. This followed close on the heels of then US President Donald Trump’s unilateral recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in return for Morocco’s normalisation of relations with Israel via the Abraham Accords.

Responding to Morocco’s violation, the Polisario declared the ceasefire dead and the SPLA began launching attacks against the Berm. Morocco responded by targeting military and civilian traffic in the Liberated Territories with drone strikes, while claiming officially that there was no war and everything was normal. The situation at time of writing (June 2024) remains one of tit-for-tat raids and retaliation, although it seems that the SPLA has become bolder in recent months, launching actions in the Occupied Territories. Nearly half a century after their European colonisers left, the Sahrawis are still fighting an asymmetrical conflict against a predatory occupier, with a combination of outdated weapons, determination, and an intimate knowledge of the desert.

Herbert wrote Dune over a decade before the start of the Western Sahara conflict. His Fremen freedom fighters clearly have Islamic roots, both in terms of their inspiration and their fictional history in the Dune universe, but do not appear to be based on any single culture. Nonetheless, the extent to which their struggle echoes that of the Sahrawi people is uncanny, as if Herbert were tapping into the prescience of some of his key protagonists. His adoption of a slogan from the Algerian War of Independence that is echoed in the language of the Sahrawi liberation struggle today seems particularly apt, given the geographic context and Algeria’s support for the Sahrawis and their cause.

The most obvious similarity between Western Sahara and the titular planet of Dune/Arrakis is the struggle of a desert people against an occupying outside force. The Fremen struggle is against House Harkonnen, a sort of monarchy, which runs its home world as a personal fiefdom, and uses Arrakis as an extension of the family business to increase its wealth through resource extraction. The resource in question is the spice melange, a vital commodity found only on Arrakis, that extends life and confers limited prescience on the navigators of the Spacing Guild, enabling them to pilot their spacecraft safely in an era when computers are banned following an apocalyptic war against AI. The spice is an obvious stand-in for oil, although Dune is no simple allegory for any one Earthly issue.

Western Sahara does not produce oil, although foreign companies are looking for it, in collaboration with the occupying Moroccan authorities. However, it is one of the world’s most important sources of phosphate, a key component of synthetic fertilisers. Between them, Morocco and Western Sahara house over 70% of known phosphate rock reserves, and account for around 15% of current annual production. Demand for phosphate is rising, and the United States’ own production is declining, increasing Western Sahara’s importance for global agribusiness and food security. Like Arrakis, Western Sahara has a vital commodity on which humanity depends, and the powers that be have devolved its extraction to a predatory colonial power at the expense of its people. Just as the imperial house in the Dune universe gives the appearance of observing accepted political conventions while secretly plotting against a new, more liberal (albeit still colonial) regime on Arrakis, so the United States, France and other key powers pay lip service to the UN mandated decolonisation process in Western Sahara while actively supporting Morocco’s occupation behind the scenes.

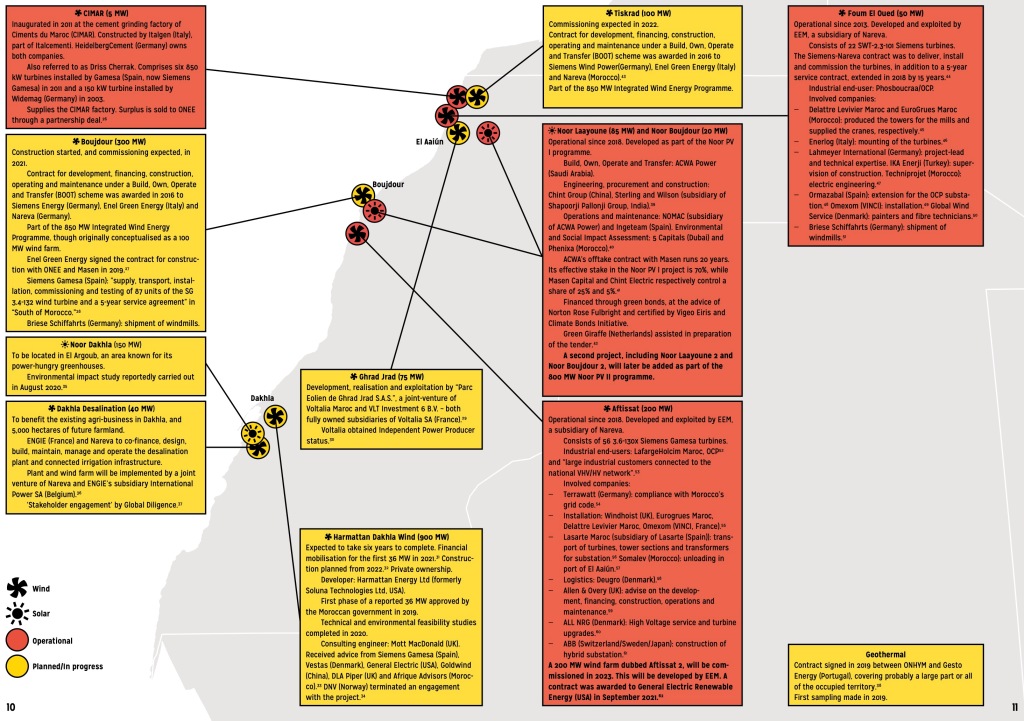

Phosphate is not the only resource extracted by the Moroccan regime from occupied Western Sahara. Fisheries are another important commodity, supported by the upwelling of nutrient rich, cold water along the northwest African coast where the desert meets the ocean. Western Sahara’s scarce freshwater resources are exploited to support agriculture in the Occupied Territories, whose products end up in European supermarkets with the country of origin indicated as Morocco. Some of these agribusinesses are personally owned by Morocco’s king. However, potentially the most important resource to be extracted from Western Sahara by its colonisers is renewable energy generated by huge wind and solar farms built throughout the Occupied Territories. This renewable energy helps power the infrastructure, settlement, and industrial activity that underpins Morocco’s colonisation of Western Sahara. Morocco has aspirations to supply Europe with green energy, opening the door to European dependence on renewable generation in the territory, providing an incentive for the EU to support the occupation. Again, the Moroccan king owns most of these wind farms.

Like Dune’s House Harkonnen, Morocco is occupying someone else’s desert, from which its rulers are extracting vital resources that they use to increase their wealth, power and influence. All this is at the expense of a colonised and marginalised people, invisible to the rest of the world as a result of Morocco’s media blackout in occupied Western Sahara. As on Arrakis, the coloniser does what it wants to the colonised people largely in the absence of scrutiny – like the Atreides, Sahrawis who oppose Morocco’s occupation die in the dark.

But, like their fictional Fremen counterparts, the Sahrawis have fought back against their oppressors, against all the odds. In Dune, the Fremen launch raids against Harkonnen spice harvesters, eloquently represented in the films as giant, tic-like machines illustrating the parasitic nature of colonialism. In Western Sahara prior to the 1991 ceasefire, the Sahrawis would attack the 150 km conveyor that transports phosphate rock from the Bou Craa mine to the Atlantic port of El-Aayoun, both located in occupied territory. Since the breakdown of the ceasefire in November 2020, the SPLA has resumed its attacks against the Berm – Morocco’s own Arrakis-style shield wall that protects the occupier from the people over whose desert it claims ownership. At the end of the first volume in the Dune series, the Fremen overthrow their occupiers in an epic battle launched under cover of a giant sand storm; I have heard tell of how, in the first phase of the armed conflict in Western Sahara, Moroccan troops stationed along the Berm lived in fear of sand and dust storms, as SPLA fighters would use them as cover for offensive actions against their positions. Although, where the Fremen ride giant sand worms, the Sahrawis have favoured Land Rovers for their agility in the desert terrain.

The Sahrawis have been struggling for their independence for decades, and have done a remarkable job of building a coherent society and maintaining a national identity in the face of extreme hardship and international marginalisation. They are not the Fremen (for a start, they are much more hospitable to strangers), but their struggles are reflected brightly in Herbert’s epic story. Western Sahara doesn’t need a Paul Atreides style saviour – given the dark messianic turn the main protagonist takes in the books, none of us do. But the Sahrawis do value international support and recognition. They have been betrayed too often and ignored too long. So, when you watch Dune, as you wonder at the spectacle on the screen, spare a thought for the real-life counterparts of the Fremen, and their ongoing struggle. If we support the principles of liberation and self-determination when we see them in fiction and on screen – in a sense, our own alam al-mithl – should we not also support those same principles in the real world?

Ya hya chouhada, indeed.

- If you’re interested in the representation of Islam in the Dune books and films, please do take a look at Haris Durani’s website, which contains links to his many great articles on this topic.

- For more information on Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara with a focus on resource extraction and the development of renewables and other infrastructure in occupied Western Sahara, you can visit Western Sahara Resource Watch.

- For more general context on Western Sahara, visit Stephen Zunes’ website, or my old Sand and Dust blog, written mostly while I was conducting fieldwork in Western Sahara.

UPDATE, 11 December 2022. Following the launch of the First indicative NDC for the Sahrawi Republic in 2021 (see the article below from November 2021), we’ve been working to highlight issues around climate change and climate justice in relation to the Western Sahara conflict. As part of these activities, I’ve prepared a briefing on theses isues which you can download here (updated August 2023). The briefing is a draft, and will continue to evolve. A more detailed post on the activities around climate change and the Wetern Sahara conflict will follow in due course.

Last week I travelled to Glasgow with colleagues from Western Sahara and the UK to launch an indicative Nationally Determined Contribution (iNDC) – essentially a national climate change plan – for the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). The launch took place at the COP26 Coalition People’s Summit for Climate Justice, and was supported by War on Want. This post provides some background to the iNDC and discusses the critical issues of climate justice that the iNDC addresses (including why it is an ‘indicative’ NDC). You can download the full text of the iNDC here (in English), along with the press release in English, French and Spanish. At the end of this article there are a number of videos from the iNDC launch, and from subsequent coverage.

The Sahrawi iNDC addresses climate change mitigation and adaptation in the non-self-governing territory of Western Sahara and the Sahrawi refugee camps in neighbouring Algeria. It also addresses issues of climate justice associated with the conflict between the Sahrawi national liberation movement and Morocco, recognised by the UN as the two equal parties to the conflict. The conflict has increased the exposure and vulnerability of the Sahrawi people to climate change impacts. At the same time, the SADR’s exclusion from global climate governance and finance mechansims means it cannot access the technical and financial support it needs to address these impacts. Meanwhile, Morocco uses these same governance and finance mechanisms to strengthen its occupation of Western Sahara. The iNDC affirms the SADR’s commitment to the goals and principles of the Paris Agreement, and provides a list of mitigation and adaptation actions.

What is a Nationally Determined Contribution?

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are documents that governments submit to the Secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), setting out the actions they intend to take to address climate change. These actions include mitigation actions, which reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and adaptation actions, which aim to reduce the impacts of climate change on people, infrastructure, the environment and so on. Actions may be unconditional, meaning that a government/country intends to take them anyway, or conditional, which means they are dependent on external technical and/or financial support. This is why there has been so much discussion about climate finance and who gets it – finance is critical for cash-strapped developing countries if they are to implement their mitigation and adaptation actions.

What is the political and historical context, and why is this NDC ‘indicative’?

Western Sahara is defined by the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization as a non-self-governing territory or NSGT. These are “”territories whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government.” In other words territories in which the decolonisation process is not yet complete.

Western Sahara was a Spanish colony until 1975, when Spain pulled out and Morocco and Mauritania invaded and claimed the territory for themselves, despite an earlier ruling by the International Court of Justice that dismissed their claims to the territory. The Frente Polisario, the Western Saharan independence movement established some years earlier, fought Morocco and Mauritania on behalf of the Sahrawi people and their right to self-determination as recognised by the UN under resolutions 621 (1988), 690 (1991), 809 (1993) and 1033 (1995), and subsequently reiterated, most recently in 2021. Mauritania withdrew from the conflict and renounced its claim to the southern part of Western Sahara in 1979, but Morocco fought on. The Polisario declared a Sahrawi state, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), in February 1976, which they intended to govern a unified, independent Western Sahara.

In 1991, the UN brokered a ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario, and established the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). By 1991, Morocco had seized around 80% of Western Sahara and constructed a 2700 km military wall, the ‘Berm‘ to secure the territory it occupied. Under the UN ceasefire, Western Sahara was divided into Moroccan occupied territory west and north of the Berm, Polisario held territory east and south of the Berm, and a ‘buffer strip’ extending 5km east of the Berm to separate the warring parties, and from which they were prohibited.

Today, over 500,000 people live in Moroccan occupied Western Sahara. Most of these are Moroccan settlers, encouraged to move to the occupied territory by their government through financial incentives. The population of native Sahrawis in the occupied territory is probably somewhere in the region of 100,000. An estmated 60,000 Sahrawi live in the Polisario controlled areas, where limited resources, minimal infrastructure and risks associated wirth renewed conflict constrain settlment. The majority of the Sahrawi population, estimated at 173,600 in a 2018 census, live in five large refugee camps around the Algerian city of Tindouf, close to the border with Western Sahara. The government of the SADR is based in the refugee camps. The SADR is a founding member of the African Union and has been formally recognised by some 80 countries. However, because of the conflict, the SADR is not yet a UN member state.

In November 2020, the ceasefire broke down when Morocco occupied part of the buffer zone, expanding its territorial occupation of Western Sahara.

It is in this context that we developed and launched the indicative NDC. Indicative, because countries can only submit a formal NDC if they are a party to the UNFCCC and a signatory to the Paris Agreement, which provides the framework for global climate governance of which NDCs are a part. To be a party to the UNFCCC or a signatory to the Paris Agreement, a country must be a UN member state. As the SADR is not yet a UN member state, it cannot be a party to the UNFCCC or a signatory to the Paris Agreement, so cannot submit a formal NDC. This ‘indicative’ NDC or ‘iNDC’ signals the SADR’s commitment to the Paris Agreement goals and principles, and its desire to participate in international process and mechanisms to address climate change. More on that below, when we address the climate justice aspects of the iNDC.

What are the climate change issues in Western Sahara?

Western Sahara and the displaced Sahrawi population (including the refugees and those who have settled in the Polisario controlled areas east of the Berm) are exposed to a number of climate change hazards and risks. Indeed, Western Sahara and the refugee camps are both highly exposed and highly vulnerable to climate change, as a result of geographic location and underlying socio-economic conditions respectively.

The refugee camps experience periodic, devastating floods that destroy homes, schools, health centres and other infrastructure, interupting food distribution, education and other activities. Floods cause fatalities and have significant impacts on physical and mental health. Floods are associated with intense rainfall events, and extreme rainfall intensity is increasing as a result of climate change, increasing flood risk.

The Polisario controlled areas of Western Sahara and the refugee camps are situated at the boundary between zones of high and extreme risk associated with heat exposure for global heating of 1.5°-3°C. Extreme risk is associated with potentially fatal wet-bulb temperatures above 34°C. These areas already regularly experience absolute temperatures above 50°C, and these episodes will become much more frequent. Extreme temperatures have impacts not just on heath but on infrastructure, for example increasing the risk of power outages.