| CARVIEW |

The post Your Infant Knows Exactly What Your Baby Talk Means appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>But baby talk may actually help babies learn to talk.

These are the findings of a study recently published in the journal Developmental Science. Researchers from the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia, wanted to know if the exaggerated pitches and other sounds typical of what’s technically termed “infant-directed speech,” or IDS, could help babies learn to tell the difference between one vowel sound and another. Vowel sounds are the ones most commonly exaggerated by adults in baby talk, research has shown, but this practice isn’t unique to infant-directed speech. Humans also tend to draw out vowel sounds when articulating in noisy environments and talking with non-native speakers.

Whether baby talk helps babies learn language has been a somewhat controversial subject. “Previous research has consistently shown that infants prefer to listen to IDS,” said researcher Varghese Peter in a statement. “But whether it has any significance beyond this is under debate.”

Read more: “When Kids Talk to Machines”

Some studies have already shown correlation: That infants whose parents use exaggerated vowel sounds appear to have better language perception abilities and larger vocabularies later. But not all baby talk features long sing-songy vowels. For example, parents who speak Dutch, Norwegian, and Danish are less likely to use them when talking to infants. Exaggerated vowels can also blur the distinctions between one vowel and the next, which could, in theory, make it harder for babies to learn how to understand and use them.

To investigate, Peter and his colleagues recruited 22 Australian adults, 24 4-month-old infants and 21 9-month-old infants and brought them into the lab. Then they played recordings of a single Australian-English mother talking in baby talk with her 9-month-old infant and in regular adult speech with someone else and recorded what was happening in the study participants’ brains using EEG recordings when they were listening to specific vowel sounds spoken in the language of baby talk. They chose these particular ages because the first year of life is critical for language development— a time when babies become more attuned to native language sounds and less sensitive to non-native ones. In the first four months, babies are mostly learning acoustic pattern matching, while the perception of different vowel categories is thought to advance in a major way between six and nine months of age.

What the team found is that 4-month-old babies had stronger, more “mature” responses to vowels spoken in baby-talk-ese—what they called a “mature” response—whereas the brains of adults and 9-month-old babies responded similarly to both baby talk and regular speech. “When they heard vowels spoken in adult speech, their brains showed a less advanced response. However, when they heard the same vowels spoken in infant-directed speech, their brains produced a more advanced response, similar to that seen in older infants and adults,” explained Peter, referring to the 4-month-olds.

“In other words,” he continued, “‘baby talk’ isn’t silly at all; it may support early language learning from as young as four months of age.”The scientists note that it’s possible vowel exaggeration isn’t the only part of baby speech that could be responsible for the ways the youngest babies responded to baby talk. Typically, exaggerated vowels coincide with higher pitches and greater pitch ranges, which could have also contributed. Another caveat: The authors focused on a specific contrast between “a” sounds and “i” sounds. For more difficult vowel contrasts, the benefits of using baby talk could extend beyond nine months, they point out.

What they found may not prove that every goo goo gaga creates a genius, but it does suggest that this linguistic nonsense has real meaning to those who actually need to hear it. ![]()

Lead art: Design_Stock7 / Shutterstock

]]>The post Spaceflight Prematurely Ages Astronauts appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>Scientists David Furman and Matias Fuentealba of the Buck Institute took blood samples from four astronauts before, during, and after a 10-day trip to low Earth orbit on the Axiom-2 mission. Working in concert with laboratories in New York City and Saudi Arabia, they developed what they call the “Epigenetic Age Acceleration” (EAA) formula to measure how gene expression and biological age are altered by spaceflight. They published their findings in Aging Cell.

Read more: “Physics Makes Aging Inevitable, Not Biology”

Overall, the team studied 32 different DNA methylation-based clocks and determined the astronauts’ epigenetic age had advanced almost two years by day seven of their trip, then quickly recovered once they were back on Earth. In fact, younger astronauts showed a biological age that had actually dropped below their pre-flight measurements.

“These results point to the exciting possibility that humans have intrinsic rejuvenation factors that can counter these age-accelerating stressors,” Furman explained in a statement. “Using spaceflight as a platform to study aging mechanisms gives us a working model that will allow us to move toward the ultimate goal of identifying and boosting these rejuvenating factors both in astronauts and in those of us planning on aging in a more conventional manner.”

In the meantime, Furman is studying the effects of microgravity on heart, brain, and immune cells in his lab on Earth, all in an effort to delay our inevitable trip to the final frontier. ![]()

Lead art: DGIM studio / Shutterstock

]]>The post Why the Do Nothing Challenge Doesn’t Do Much for You appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>It’s a new twist on an old idea. Over a decade ago, South Korean artist Woopsyang started the “Space-Out Competition” to combat burnout. Since then, the urge for stillness has evolved in many forms, including the recent mania for rawdogging, a term that’s come to mean enduring any mundane activity without aids, particularly long flights. That trend became such a sensation that the American Dialect Society chose rawdog as its Word of the Year in 2024.

But the Do Nothing challenge and the rawdogging trend suggest a fundamental misunderstanding of how boredom and disconnection work, says James Danckert, a researcher in the Boredom Lab at the University of Waterloo. Boredom is closer to hunger than to holiness, he argues, and forcing it on yourself for hours on end doesn’t by itself have restorative power. Instead, the feeling suggests something about your attention, agency, or meaning is out of alignment.

I spoke with Danckert about why we’re so fascinated with boredom in this cultural moment, why some people have more trouble with boredom than others, and his frustration with the stubborn idea that boredom is fertile territory for creativity.

Why do you think we’re so fascinated by boredom of late?

In the early 2000s, we’d start all of our scientific papers with “boredom is an understudied phenomena,” but we can’t do that anymore because in the last 20 years, a lot more people have begun researching it. Some of the recent work aims to understand the relationship between social media and boredom. You might think that there’s so much at our fingertips now, surely boredom is gonna go away. But what we’re finding is that it’s actually increasing. So one speculation is that our capacity to connect well is diminishing, and as that’s happening, we’re getting more bored.

Read more: “What Boredom Does to You”

It seems like boredom means a lot of different things to different people. Is there a good standard scientific definition of boredom?

There’s a distinction to be made here that’s important. State boredom is the in-the-moment feeling of “I am bored right now.” Functionally what is it doing? It is meant to signal to you that what you’re doing right now isn’t working. You need to do something else. And then there’s trait boredom, or boredom proneness. These are individuals who experience boredom frequently and intensely, and it makes them feel like their lives are just lacking in meaning.

Are there any real downsides to forced boredom? These TikTokers who are filming themselves doing nothing for hours and hours and hours. Is that actually restorative?

The ultimate goal of in-the-moment feelings of boredom is to eliminate itself. Boredom wants to not exist, right? And so, to embrace boredom and say, “Oh, I’m gonna try and rawdog it on this flight for 12 hours.” It’s just a stunt. And it’s not listening well to what boredom is actually telling you, which is to find something meaningful to do.

@kareemrahma Just rawdogged my longest flight yet. #bareback #rawdog #airplanes #flights #travel

♬ Motivational – Vioo Sound

But the other thing is that they’re misconceiving their own needs. They don’t want boredom. They want disconnection. And that’s perfectly fine. We used to talk about this in other ways: vegging out, or just relaxation for Christ’s sake. So anything that takes you out of the normal everyday stresses that we all experience. But I think we ought to intentionally choose those times and activities that are our disconnection times—and rawdogging boredom ain’t it. That’s just a fundamentally dumb idea. In the one or two examples that I’ve looked at, what I saw is that they’re uncomfortable, right? So they’re at least experiencing one of the key features of boredom. But when you want to disconnect from the hustle and bustle of your life, why would you intentionally engage in a thing that feels bad? It doesn’t make sense to me.

People claim that boredom is like a form of mindfulness, or it helps them address feelings and thoughts that maybe they were too afraid to confront. And both of these things can certainly be uncomfortable. How do you know the difference between the discomfort of boredom and say the discomfort of mindfulness or meditation?

Mindfulness practice, as I understand it, isn’t typically described as uncomfortable. It might allow you to deal with thoughts and experiences in your life that themselves are uncomfortable. But the practice of being mindful is generally considered to be quite positive, I would think. Mindfulness is also a practice. It’s a thing that takes time to get good at. So you can’t hope to just do a one-hour session of mindfulness and solve all of your problems. You need to practice this over a number of months and years.

In 2014, Timothy Wilson and his group published a research paper titled “Just Think.” They put people in a room for 15 minutes with nothing but their thoughts. They took away their cell phones. There was nothing to look at in the room. You couldn’t do anything. You just had to sit in a chair, you and your thoughts. Then they asked you how it felt. And one thing that got lost in the media frenzy around this particular paper was that actually one-third of the participants rated the experience to be quite pleasant. One-third were ambivalent, and one-third hated it. They just thought it was boring and terrible. Again, the paper included nine experiments, but the one that got the media attention was this one that involved either sitting in a room for 15 minutes with nothing but your thoughts—or you could self-administer an electric shock.

And people had experienced these electric shocks before the 15 minutes began. They’d rated them to feel negative and bad. They’d said that they would pay certain amounts of money to not experience them again. And then when you put them in there for the 15 minutes, still some significant percentage—more men than women—administered these electric shocks, rather than sit there and do nothing. One guy administered 196 electric shocks in 15 minutes to himself. To me, what that says is that we evolved for action, not for thought. Thought is a great and wonderful thing. Language is a great and wonderful thing. But we evolved to control our bodies and interact with the environment around us.

Boredom is also common where we feel constrained—when we have no autonomy and no agency. So we don’t feel like we can act in ways that we want to act. So these are examples and data that suggest that rawdogging boredom on a flight is just a silly idea. It’s going against what we’re actually evolved to do. Instead, what you might want to do is to say, “Okay, I’ve got a boring flight ahead of me. What would be a meaningful thing that I can do?” It could be something as simple as trying to complete the hardest Sudoku you’ve ever done. It doesn’t have to be meaningful in the sense of curing cancer, but something that matters to you is a better thing to attempt on a long flight than just trying to sit with it and do nothing.

You mentioned earlier that some people are more prone to boredom, and in other talks I’ve heard you say that this is connected to problems with self-control and self-esteem. Why?

We’re actually still working on that. But self-control seems to be a cluster of processes that allows you to effectively pursue your goals. It allows you to marshal your thoughts, actions, and emotions in the pursuit of what matters to you. Often what you see in the literature is that people talk about self-control primarily as a challenge of inhibition. But for boredom proneness, I actually think that it’s a different kind of self-control that they struggle with—what we call a struggle to launch into action. When a young 5-year-old child comes to you and says, “I’m bored,” you, as a parent, tend to have this sort of knee-jerk reaction to say, “Why don’t you do this? Why don’t you go play with your Legos? Why don’t you go play outside? Why don’t you go and do a drawing? Why don’t you read a book?” The child knows all of those options are available. They just don’t want those things at this time. That’s the problem of boredom proneness. You don’t want what’s available right now, and you don’t know what you do want.

That’s so interesting because a study just came out about motivation in macaques, specifically related to getting started on a task, even one that’s expected to be rewarding. They found basically that there’s this one circuit in the basal ganglia of the brain that when it’s inhibited, the monkeys could get started, even if the reward came with an unpleasant punishment. Whereas if the circuit was active, they couldn’t. As far as you know, is there a signature of boredom in the brain?

So the answer to that would be no. There’s really great work from Lisa Feldman Barrett talking about this notion of signatures of any kinds of affective experiences. And I think we’ve been hunting for that for decades. You know, what’s the signature of happiness? What’s the signature of anger? The answer is, there just really isn’t one physiological or neurological signature. We have these large-scale networks that are important for interacting with the world. And there’s just a ton of overlap.

But one part of the brain that seems to be very interesting for boredom is the insular cortex, which is very important for representing what we call interoceptive sensations, or internal body sensations. So feelings of hunger and thirst, butterflies in the stomach, a racing heart. And what Feldman Barrett suggests—she focuses a lot on depression and a little bit on anxiety—is that we use these internal body states to predict how we’re going to feel later on. So the boredom-prone person might just have faulty anticipation of reward. They might not know what’s going to feel good. They might not know what’s going to be engaging or might not be using these internal signals accurately. We’ve published some work on that that shows that people who are boredom-prone pay a lot more attention to their internal body states, but they’re kind of confused by them. They don’t make sense of them as well. There’s a concept known as alexithymia, which is the difficulty of labeling and discriminating your affective states, and people who are boredom-prone tend to have higher levels of alexithymia, as well.

Some researchers suggest there’s a relationship between boredom and creativity. Do you think there is any merit there?

The creativity idea has been a bit of a bugbear of mine, and a number of my colleagues who do boredom research feel this way, too. I think there’s this great desire in people to want to believe that boredom will somehow make you creative. But if you think about it, the logic just doesn’t work. So I start thinking about, “Where does the desire come from?” Famous people will often say, “I was bored, so I did X.” And because we look up to famous artists, we think, “Oh wow, boredom must be a really helpful tool in making you creative.”

The story I’ve used in the past a lot is from Jimi Hendrix. Somebody sees Jimi Hendrix play for the first time, and is just blown away and corners him backstage and says, “Man, where have you been hiding?” And Hendrix replies, “I’ve been playing the Chitlin’ Circuit, and I was bored shitless.” A Chitlin’ Circuit was something in the ’50s and ’60s in America that was a sort of safe circuit of venues for Black Americans to perform anything from stand-up comedy to music to whatever. But the kind of music that was expected in the Chitlin’ Circuit was old and not to Hendrix’s liking. So he did something else and became the guitar virtuoso that we know. But the logic there is all wrong. Boredom didn’t make Hendrix a genius. Practice made Hendrix a genius. Trying to do different things made Hendrix a genius.

Creativity is a wonderful solution to boredom, but you can’t hope that it works the other way around. So the paper from 2014 that everybody cites that says boredom makes you creative: There’s loads and loads of problems with that paper. We tried to replicate it and found the opposite: The more bored we made people, the less creative they were.

@themichaelbarrymore Not even any music on, did this in silence

♬ Lullaby for Erik – Evgeny Grinko#timepass

I would think that people who get bored easily tend to seek out novelty more.

That’s a reasonable conclusion to come to, but we have actually struggled to find that. People who are prone to boredom want novelty, but they fail to launch into action. Now, the temporary state itself might work exactly in the way that you suggested—that it pushes you toward novelty seeking. But novelty seeking alone isn’t gonna make you creative either. It’s what you do with that novelty, what you do with the new thing that you find and come back to practice.

You have mentioned elsewhere that animals feel boredom. How do we know?

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen a mink in the wild. They scamper around. They look like they’re mischievous little creatures. And we still farm them for their fur, which is disgusting. But what Georgia Mason and Rebecca Meagher did is they had two groups of mink housed in different types of cages. One group is in cages that we normally keep them in on our fur farms, where there’s just nothing for them to do. Very boring. The other one was a cage that had lots of little things for the mink to play with.

They housed these two groups for two weeks in the different types of cages. At the end of the two weeks, they exposed the animals to different kinds of items. They exposed them first to items that the animal would normally approach—apparently for mink, a toothbrush is like a laser pointer for a cat. They just go crazy for it. They love toothbrushes. So they expose ‘em to something like that, that they would normally approach. Then they’d expose them to things that they’d normally avoid—the silhouette of a predator or the smell of urine of a predator. Things that they would shy away from. And then the third group of things was neutral stuff. Stuff the animals had seen before—just a bottle of water or something like that.

The logic was this: If the animals in the cage with nothing to do were depressed, they’d show less interest in the toothbrush stuff they normally liked ‘cause they were depressed. If they were apathetic after the two weeks in the cages, they’d show no interest in anything. They wouldn’t show approach or avoidance behavior. They wouldn’t care about any of the items. If they were bored, they’d approach everything—and they’d approach even things that they’d normally avoid, like the silhouette of the predator. And that’s exactly what they found. The minks in the cage with nothing to do for two weeks rapidly—more rapidly than the other group—and indiscriminately approached all kinds of items as if they were desperate for stimulation and just wanted something to do.

What made you want to study boredom?

Two things motivated me to get into boredom research. One was that, as a late teen, early 20-something young person, I started to experience boredom a lot and hated it. I wanted to find ways to eliminate it from my life. I no longer think that that’s either possible or desirable. But around about the same time, my brother had a motor vehicle crash where he suffered a fairly serious brain injury. Months later, after serious rehabilitation, he’d report that he was bored a lot. And to me, that suggested that something organic had changed in his brain. Some consequence of that brain injury made things that were once pleasurable seem boring. And so, I wanted to understand what had happened in the brain to make that the case for him.

Has studying boredom helped you feel less bored?

I don’t think studying it has made me feel less bored. I think time has made me feel less bored. That’s one of the things that the data shows: Boredom rises in our teenage years and then starts to drop off in the late teens and early 20s. There’s a great study from Alycia Chin and colleagues called “Bored in the USA.” In our middle decades, when we’re busy with our careers, our children and all that kinda stuff, boredom drops off, because you don’t have time for it. Then it starts to rise again in the 60s and 70s. And what we’re starting to pursue a little bit more is that that’s probably about loneliness as much as anything. And so, in those later decades, people who are more socially connected experience boredom less. There’s some great work from my colleague Mark Fenske, who’s shown recently that hearing loss in the elderly is predictive of boredom.

So studying boredom hasn’t made me less bored, but over time and with all of the pressures of life, I don’t feel bored nearly as much as I used to. I’m hopeful that in my later decades I’ll pay attention to social connection—and avoid boredom. ![]()

Lead image: Master1305 / Shutterstock

]]>The post How Coastlines Shape the Extinction Risk for Marine Invertebrates appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>The researchers looked at about 300,000 fossils representing more than 12,000 genera of ocean invertebrates that lived over the past 540 million years on shallow, continental shelves. By reconstructing the arrangements of the continents during the organisms’ lifetimes, they estimated the geometry (both shape and orientation) of the coastlines they inhabited. Then, by statistically modeling the relationship, they tested the hypothesis that coastline geometry influenced extinction risk.

The data showed that organisms inhabiting north-south-oriented coastlines, like today’s North American coasts, had a better chance of long-term survival when conditions changed. The study authors hypothesized that the north-south coastlines offered a corridor for organisms that rely on shallow waters to migrate and stay within their tolerance ranges when climate or other conditions changed.

Read more: “Our Boiling Seas”

Organisms that lived alongside islands, inland seaways, or east-west-oriented coastlines like today’s Mediterranean Sea coasts were disadvantaged when conditions changed. Migration to newly suitable habitats was likely impossible, short of crossing the open ocean. As such, these coastal invertebrates, which have limited abilities to traverse long distances, faced what the researchers dubbed “latitudinal traps.”

“Groups that are trapped at one latitude, because they live on an island or an east-west coastline, for example, are unable to escape unsuitable temperatures and are more likely to become extinct as a result,” explained study author and earth scientist Erin Saupe in a statement.

During mass extinction events or periods that were particularly warm, the role of coastline geometry in extinction risk was more pronounced. The geographic constraints imposed by the shape and orientation of coastlines appeared to have amplified importance in driving extinction during periods of elevated environmental stress.

“This work confirms what many paleontologists and biologists have suspected for years—that a species’ ability to migrate to different latitudes is vital for survival,” concluded lead author and earth scientist Cooper Malanoski in a statement.

These patterns detected over millions of years might apply to modern species. Organisms living in “latitudinal traps” of east-west coastlines or islands may be especially vulnerable to dramatic changes in conditions.

The study calls for paying attention to coastline geometry in predicting and mitigating how species will endure continuing climate changes. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Erik Lukas / Ocean Image Bank

]]>The post Some Doctors Are Using Emojis With Patients More Often appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>Healthcare providers have already been found to incorporate emojis and emoticons—their vintage counterparts—into texts with colleagues on a clinical messaging platform, according to a 2023 JAMA Network Open study. Now, researchers say they’ve conducted the first study examining emoji use in electronic health record clinical notes, which includes portal messages sent to patients. Compared with the 2023 paper, doctors seem to use them a lot more when chatting with patients than with their coworkers.

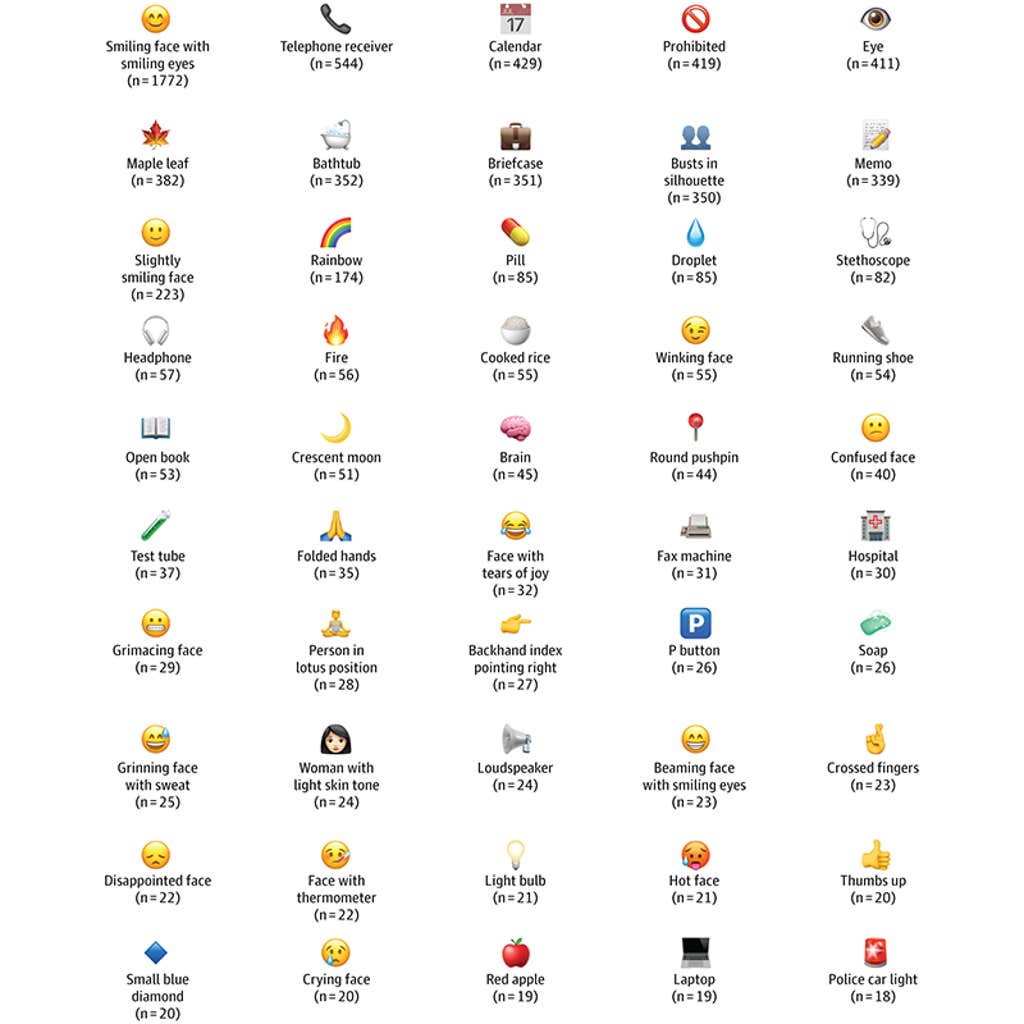

A team from the University of Michigan and Cornell University sifted through more than 200 million notes sourced from 1.6 million patients created between 2020 and 2025 at the University of Michigan’s academic medical center. They identified 372 unique emojis used in 4,162 notes, findings recently published in JAMA Network Open.

While the rate of emoji inclusion stayed relatively stable at 1.4 notes with emojis per 100,000 notes between 2020 to 2024, it suddenly jumped to 10.7 by late 2025.

“These were scattered throughout clinical notes but were mostly found in brief messages sent to patients via the portal,” said study co-author David Hanauer, a clinical informaticist at the University of Michigan, in a statement. “While emoji use in medical records is still rare, their use seems to be on the rise, raising important questions about age-related differences in use and interpretation, as well as best practices for digital clinician-patient communication.”

They noticed that smileys ( ) or emoticons such as the classic : ) were the most commonly used type of emoji, appearing in 58.5 percent of notes, along with objects, like a pill (

) or emoticons such as the classic : ) were the most commonly used type of emoji, appearing in 58.5 percent of notes, along with objects, like a pill ( ) and maple leaf (

) and maple leaf ( ), in 21.2 percent, and emojis related to people and the body in 17.6 percent. As for the most popular specific emoji, the smiley came out on top, with far more appearances (1,772) than the second most popular, the telephone receiver (

), in 21.2 percent, and emojis related to people and the body in 17.6 percent. As for the most popular specific emoji, the smiley came out on top, with far more appearances (1,772) than the second most popular, the telephone receiver ( , 544).

, 544).

Read more: “Your  On Emoji”

On Emoji”

Emojis were very rarely incorporated in messages to replace a word, such as a pill bottle for the word medicine—this only occurred among 1 percent of all emojis that the researchers analyzed. Most served to highlight a point, or were included “for their own sake,” the statement explained. This aligns with past findings that emojis tend to be employed to reduce ambiguity and shape a message’s tone.

But these symbols may not always clear things up—they could create confusion, especially for older patients, the authors noted. Patients between 10 and 19 years old received the most emojis per 100,000 portal messages from providers, followed by patients between 70 and 79 years old. Some studies have suggested that older adults are less likely to accurately interpret emojis than younger people, but researchers haven’t reached any clear conclusions. Other factors, like gender and culture, may also affect one’s understanding.

“Given the small but growing presence of emojis in clinical documentation, we recommend that healthcare institutions proactively develop guidelines for their use to maintain clarity and professionalism in clinical communications,” Hanauer said in the statement.

Further research should probe how emojis seem to influence “patient understanding, trust, and outcomes and explore whether these playful digital symbols offer new opportunities or pose unintended challenges in electronic health record communication,” he added. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Roman Samborskyi / Shutterstock

]]>The post In Pursuit of a Psychedelic Without the Hallucination appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>But the hallucinations that come along for the ride can sometimes spell trouble for people with other psychiatric illnesses—triggering psychosis in those who have schizophrenia, or in those with a family history of psychosis. The costs of providing caretakers to help safely guide people through these mind-bending trips can also make the drug too expensive for many.

Now, some researchers are asking whether they can create a drug with similar benefits but with a little bit less magic: providing the mood-boosting effects but doing away with the hallucinations. The researchers, from Dartmouth University, recently identified a neural receptor that could be a potential target for such a drug, reporting their findings in Molecular Psychiatry.

“When people think about psilocybin, they think about acute effects like hallucinations, which are attributed to the activation of a specific neuroreceptor,” explained Sixtine Fleury, the study’s first author and a psychology and brain sciences researcher at Dartmouth, in a statement. “We thought that the beneficial effects reported for treating depression and anxiety may be found in other receptors.”

Read more: “The Psychedelic Scientist”

The long-lasting antidepressant effects of psilocybin are often credited to a single receptor in the brain: 5-HT2A, which also happens to be the one most closely tied to hallucination. But psilocybin’s “active” form psilocin—the part of the compound that actually binds to receptors in the brain after it’s ingested—attaches to many binding sites in the brain’s serotonin system, a neurotransmitter pathway that helps to regulate mood, sleep, appetite, and social behavior, among other things.

“Our study shows that there likely is another target,” explained study author Katherine Nautiyal, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth. “Researchers have narrowly focused on the 2A receptor because we know it causes hallucinations, but the screening profiles of psilocybin show that these drugs bind to nearly all of the serotonin receptors.”

The scientists wondered if a receptor known as 5-HT1B, which has already been implicated in reward processing, anxiety, and plasticity, all relevant to depression, might play a role in generating the positive and long-lasting mood effects of psilocybin. To check out this hypothesis, they ran a set of experiments in mice, which have a serotonin system similar to that of humans. They wanted to see if psilocybin worked differently when the 5-HT1B receptor was blocked so they tested it in three different ways before administering the drug.

First, they removed or blocked the 5HT1B receptor, using genetic engineering to create mice that lacked it. Next, they allowed mice to develop with normal 5HT1B receptors, but blocked these receptors when the mice were adults. Finally, they gave the mice drug blockers that muted the receptor right before they gave them the psilocybin. Then they injected psilocybin into the three different sets of mice and watched what happened in their brains using imaging and network analysis. They also measured behavior in the mice, both immediately after the injection and days later, such as how they navigated a maze or an open area, or how long it took them to start eating in a bright, stressful area.

What they found is that the 5-HT1B receptor really mattered for the longer-lasting, mood-relevant effects of psilocybin in mice. But activating 5HT1B alone didn’t recreate psilocybin’s full effects. In one of the stress tests, the benefits were mostly found in females, but another showed effects in both sexes—a reminder that there’s no one-size fits all response for psilocybin effects, even in mice. Still, the findings are a promising starting point.

“These substances have the potential to open new avenues for clinical therapy and therapeutic drugs,” Fleury said. “It’s important to find better treatments that are more efficient and more effective for people, but it’s also important that we have a safe way to do that.”

Their hope is that taking a psychedelic trip can heal the brain without the psyche leaving the comfortable grounding of Earth. ![]()

Lead image: Fotema / Shutterstock

]]>The post As Biodiversity Dwindles, Mosquitos Turn to Human Blood appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>A new study published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution shows that mosquitoes along the east coast of Brazil are taking blood from humans more often than from any other animal.

Researchers from Brazil’s Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro and Instituto Oswaldo Cruz examined the diets of mosquitoes inhabiting the humid Atlantic Forest. What used to be an intact forest has been increasingly colonized for human activities, such that only about a third remains wild. As humans edge other vertebrate animals out of their habitats, mosquitoes may have to retool their diets.

Using light traps over two consecutive days, the researchers captured nine species of female mosquitoes. Of the 1,714 individuals captured, 145 were engorged with blood from recent feedings. The researchers sequenced DNA from blood in their stomachs, and, using a reference database of vertebrate DNA barcodes, were able to identify the sources of the blood meals from 24 mosquitoes. These sources included 18 humans, one amphibian, six birds, one dog, and one mouse. Some mosquitoes had blood from more than one feeding event in their guts.

Read more: “When Disease Comes for the Scientist”

By numbers, humans were the favored meal source. “With fewer natural options available, mosquitoes are forced to seek new, alternative blood sources. They end up feeding more on humans out of convenience, as we are the most prevalent host in these areas,” hypothesized study author and microbiologist Sergio Machado in a statement.

Unfortunately for us, mosquitoes are known to readily adapt to different food sources in their environments.

With more than 700,000 people dying annually from diseases caused by mosquito-borne pathogens, mosquito diets are a serious concern, according to the study authors. They recommend that mosquito-control strategies consider their demonstrated feeding preferences as part of the risk equation. The continued deforestation of the Atlantic Forest is likely to continue to shape the feeding behavior of mosquitoes, as “the loss of native vegetation is associated with an increase in the transmission of etiological agents of arboviruses (dengue, Zika, Chikungunya, and yellow fever),” wrote the researchers.

In other words, more people, relative to other animals, shift the mosquito cafeteria toward humans. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Loomo Digital / Shutterstock

]]>The post Watch This Glacier Race into the Sea appeared first on Nautilus.

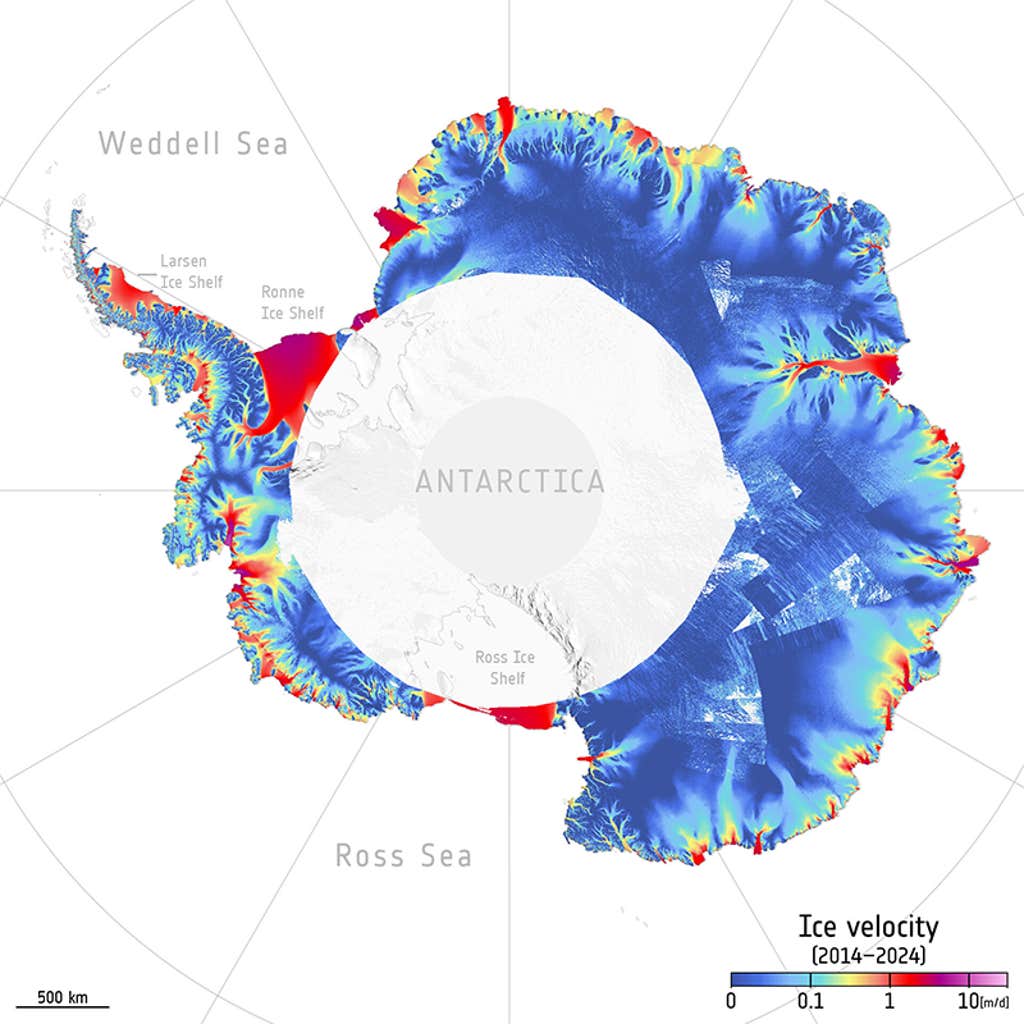

]]>These findings came from the first continuous, high-resolution survey of ice-flow speeds across the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. This information is vital in keeping tabs on the break-up of ice sheets and gauging how the world’s seas will rise in the coming decades. We already know that the Arctic is heating up quicker than the rest of the globe, and that Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are melting six times faster than in the 1990s.

Before this recent ESA mission, satellites had only taken snapshots of a few glaciers in Antarctica and Greenland or collected infrequent data. Some teams have examined glaciers over time with optical imagery from satellites, which captures what’s visible to the naked eye. But this limits monitoring to the daytime, and clouds or smoke can block the satellite’s view.

A technology called synthetic aperture radar (SAR) clears these hurdles by beaming out energy pulses and measuring the amount of energy reflected back from these glaciers. Between 2014 and 2024, an instrument on Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellites collected SAR data to trace the ice’s travels.

Read more: “The Hidden Landscape Holding Back the Sea”

The vibrant visualizations of the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica were created by a team from ENVEO IT, an engineering company based in Austria. They applied specialized algorithms to the SAR measurements, according to a Remote Sensing of Environment paper, generating maps that display average ice speeds over the decade-long satellite survey period.

“Before the launch of Sentinel-1, the absence of consistent SAR observations over polar glaciers and ice sheets posed a major barrier to long-term climate records,” explained study co-author Jan Wuite of ENVEO IT in a statement. “Today, the resulting velocity maps offer an extraordinary view of ice-sheet dynamics, providing a reliable and essential data record for understanding polar regions in a rapidly changing global climate.”

In the future, ESA will continue to keep an eye on the speed of these ice sheets from space thanks to the ROSE-L satellite mission that’s slated to launch in 2028. ROSE-L will harness a similar SAR instrument to track the flow of ice, offering a detailed look into what the warming future holds. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: ESA (Data source: Wuite, J. et al. 2025)

]]>The post The First Observation of the Fiery Lifecycle of a Massive Solar Storm appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>Unfortunately, these flares can be difficult to predict. That’s in part because, rather than just sitting idle at the center of our solar system, the sun rotates on its axis once every 28 days, meaning we can only observe solar storms forming on its surface for two weeks before they spin out of view. Or at least that was the case before the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Solar Orbiter mission in 2020.

Orbiting the sun every six months, this spacecraft keeps an eye on the far side of the sun while researchers on Earth watch the near side. Recently, Harra and Ioannis Kontogiannis of ETH Zurich collected data from both vantage points, observing a powerful solar storm brewing—the strongest in over 20 years—for an unprecedented 94 days. They published their findings in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Read more: “The 315-Year-Old Science Experiment”

“This is the longest continuous series of images ever created for a single active region: It’s a milestone in solar physics,” said Kontogiannis. With the Solar Orbiter, the team was able to watch as the magnetic tempest formed, became increasingly complex, flared, and then decayed.

They hope these unprecedented observations will improve the accuracy of solar storm forecasts so that we can better understand—and ultimately better prepare for them—on Earth. While the Solar Orbiter has proved to be indispensable in this mission, scientists still aren’t able to use it to predict how severe solar flares will be, but help is on the way.

“We’re currently developing a new space probe at ESA called Vigil which will be dedicated exclusively to improving our understanding of space weather,” Harra said. That spacecraft is scheduled to launch in 2031.

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: ESA / AOES

]]>The post I Turn Scientific Renderings of Space into Art appeared first on Nautilus.

]]>Calçada’s journey into astronomical art began when he spied Contact, a 1985 work of science-fiction by Carl Sagan, as a kid in a bookstore. The cover showed an inky Earth floating in a sea of darkness, a mysterious fingerprint of light emerging out of the milky abyss. Calçada was so struck by that vision that he asked his parents to buy him the book on the spot. After he read it, he devoured all of Sagan’s other books. And that set him on his path.

Calçada started out studying astronomy and physics, but he soon learned that he was more interested in the ways a beautiful image can trigger an emotional tug to understand. So he left astronomy for art. We caught up with Calçada to talk about the relationship between beauty and scientific understanding.

Your images are lush and cinematic. Do you think beauty can ever get in the way of scientific truth?

I think beauty is a trigger for curiosity, because the fascination with something extraordinary—the way a star works, or the explosion of a supernova—makes people want to understand it. Sometimes, when I see people fascinated by more mystical things, or I have conversations with friends about, let’s say, astrology, I’m like, “Why are you fascinated by those topics?” Science alone is so beautiful, and there’s so much magic there.

Have you ever argued with a scientist over artistic license you took in one of your illustrations?

There are a few kinds of scientists here at ESO. When you’re working on a press release, sometimes you get those who are extremely happy with whatever you give them. Because quite often they’re just working on data and code and plots. But when they see a nice interpretation of their data, they’re quite happy.

But there are other scientists who tend to say, “Oh, but maybe this could be like that.” And sometimes there’s a bit of a struggle to massage them into understanding that what they’re suggesting is actually not relevant for the story, or important for the general audience. Of course, we always want to make these illustrations as true to the science as possible. But it’s our job as communicators to understand what message we want to transmit to people, right? Because sometimes the science is quite clear for us, and for our scientists, but for the audience it’s not. So it’s about what we’re trying to communicate.

Can you give me an example of something a scientist wanted to change?

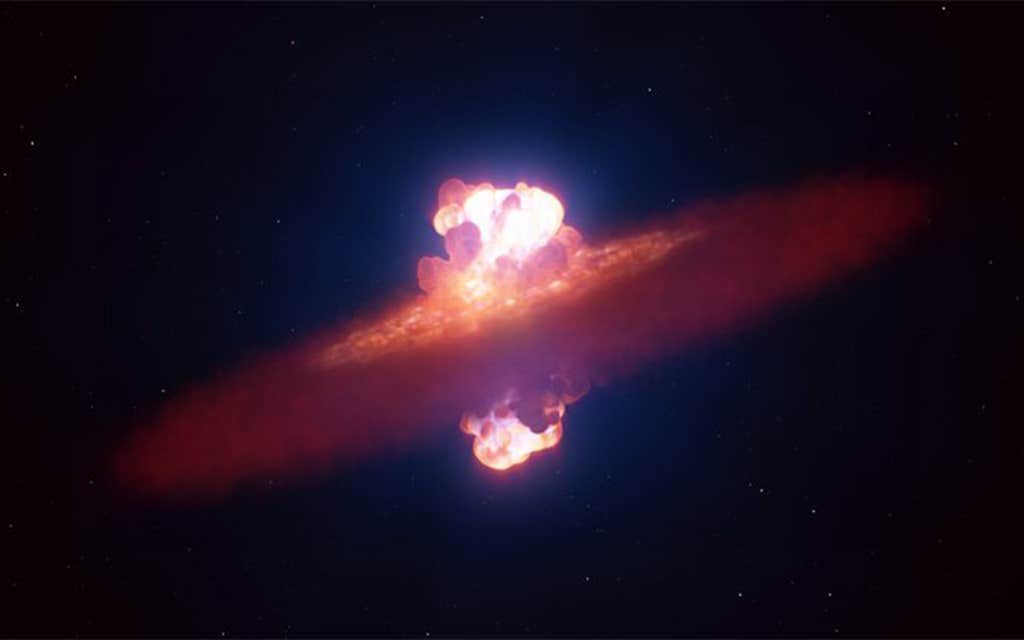

One recent project comes to mind—the simulated explosion of a star going supernova (published in November of 2025). One of the scientists—he’s a brilliant person—paid too much attention to the details. And we had a lot of back and forth, trying to negotiate some things that shouldn’t go into the illustration and the animation. For example, in this illustration, we see a few things happening at once. In the real world, these things would happen at different timescales. The first outflow from the poles of the exploding star, maybe that would happen very fast. Whereas the other parts of the explosion would happen over seconds. And then the rest of flowing out happens maybe in days, and we’re showing it all in just 20 seconds of animation.

That’s why it’s important for us to always include captions for the images on our website. We send those captions to the journalists, very clearly explaining, this is an artist’s impression. But we also understand that these animations and illustrations have a life of their own. They get reproduced elsewhere on websites, and the caption gets lost. They can sometimes be harmful as well.

What kind of harm do you think they can cause?

Harmful is probably a strong word. But they can create a false impression about what the universe really looks like. We’ve done so many illustrations of colorful events, but to human eyes, most of the universe is just black, empty. The timescales are also sped up for a lot of these things. Back in the day when I was doing some activities with the general public as an astronomer, when you’re trying to show them things in the telescope, they’re expecting to see this very colorful, dramatic scene. And you’re like, “Can you see it?” And they’re like, “No, I don’t.”

Do your images ever serve as visual hypotheses? Or are they always explanations of a settled idea or a finding that’s been established?

We try to be very careful about how much these images are guessing. I think the role here is the science, the discovery. And we’re just trying to help the science get to the public. Many times, a nice, colorful, exciting image helps a lot for a finding to get onto the cover of a magazine or in The New York Times.

How do you balance realism against imagination?

This one of the exploding supernova actually triggered a bit of a debate. There was some negativity surrounding this particular image, because some people thought it was too realistic looking. And that’s a danger. I saw people complaining. Some people were like, “Why are you showing this? Why are you not showing the supernova itself?” Because the actual supernova image was just a few pixels, so it wasn’t very interesting. What we tried to show is what the astronomers inferred through these complex methods.

The scientists were really happy at how well we portrayed the phenomenon in the end, but it triggered an internal discussion about ways of using these images. Even this week, we had more discussions about future use of AI in our work, ethical issues. Because it’s true that people may start getting fed up with this kind of overflow of bright, colorful images. And our work that’s tightly developed with scientists might get lost in that noise. We have to explore ways of cutting through the noise.

Read more: “The Art of Quantum Forces”

What are some ways you might do that?

I use Reddit quite a lot, and I saw some people commenting along the same lines, calling it AI slop, and so I kind of pitched in on the conversation. I actually tried to explain a bit about the process with the scientists. It was quite cool to see the surprise in some of the people on Reddit. So maybe what we have to do is to engage in some of those conversations, convey some of the science behind these images.

Because ultimately the goal is communicating the science—not just to make pretty pictures. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: This illustration shows what the luminous blue variable star in the Kinman Dwarf galaxy could have looked like before its mysterious disappearance. A luminous blue variable star some 2.5 million times brighter than the sun. Stars of this type are unstable, showing occasional dramatic shifts in their spectra and brightness. Credit: ESO / Luís Calçada

]]>