| CARVIEW |

In addition to the talent, there has been an unexpected and mutual support system that wouldn’t be possible any other way. I’ve had the privilege to meet three of those bloggers in person, and in each case there was no discomfort, no ice that required breaking, no need for small talk. It was like reuniting with old friends. Such is the power of this immediate and intimate medium.

Blogging has helped me become more disciplined. I always thought I worked hard at writing – editing, revising, polishing, proofreading, and then running through the same cycle, again and again. But blogging pushed me to another level, maybe because getting older has brought with it an enhanced awareness of my own weaknesses. My heart freezes when I spot a typo, or when I just think I do. A clumsy sentence, or even a misplaced comma, gets me out of bed at night. I’ve gone back and made minor changes to old posts that nobody will ever read again.

I’ve also learned how to adhere to self-imposed schedules and deadlines. As a result, I’ve developed a sense of balance that has allowed me to walk with a little more confidence along that fine line between the restraints of time and a desire for perfection. One of my college professors told me that writing can never be flawless, and I finally understand what he meant. As we attempt to translate our tangled thoughts and emotions and arrange them in a kind of order — using nothing more than twenty-six letters and a handful of punctuation — essential elements are bound to get lost in the process. At some point, we have to decide that we’ve gotten close enough to the goal. I don’t remember what I originally set out to accomplish with this blogging thing, but I’ve rarely felt that I succeeded in getting close enough. Still, it’s as close as I’m going to get, because I have to stop.

This will be my last post.

There are several factors that went into this decision, but the primary one is financial. A lot of people are struggling to earn a living these days, and I’m one of them. And that’s my own fault. For the past three decades, I’ve stubbornly marched myself straight into a corner, ignoring the fact that I lack the educational credentials or the marketable skills to do anything but write. That single-mindedness left me with few options. Now I have to find a way out of that corner, and I suspect the task is going to occupy every one of my fumbling brain cells.

I’d slipped easily into a natural rhythm of publishing a post every eight days. I’ll miss that familiar routine. I’ll miss the long searches for the right word, the right illustration, the right focus.

Most of all, I’ll miss you.

Please know that I’ve cherished every relationship we’ve built, as well as every comment and email we’ve exchanged. Your consistent encouragement has lifted me when I’ve most needed it, and your own boundless gifts have been a treasure to discover. If blogging is a shortcut, you made me glad I took it.

]]>

“The debate is over.”

Al Gore said that about man-made climate change. A lot of other people have said it, too. But it isn’t true. If the debate were over, then no one would be debating it anymore. There was a time when it was widely believed that there were canals on Mars and bathing was unhealthy, and just a few decades ago doctors said cigarettes were good for us. Those debates are over.

When you announce that the conversation has ended while someone is still disagreeing with you, it does nothing to lure them over to your side. In fact, it accomplishes the opposite. We don’t like to be told we’re wrong, but we really don’t like to be told that we aren’t intelligent enough to recognize the facts. Such an assertion causes us to dig in and cling more fiercely to our position.

That’s easy to do in a discussion about climate change, because there are more than enough facts to go around. The processes involved are complex, interconnected, and slow. If we heard that the Leaning Tower of Pisa had fallen over, we could fly to Italy and see for ourselves. But when it comes to the weather, and human influences on it, many of the facts seem contradictory. There are experts who say the earth is getting warmer, but others claim we’re going through a cooling period. Books and magazines tell us that islands in the Pacific have become uninhabitable because of rising seas, while the islands themselves maintain tourism boards with websites that beckon us to come there on our next vacation. Scientists on one side insist that elevated levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere cause higher temperatures, but scientists on the other side say that if the two factors are related, it’s the higher temperatures that cause increased levels of carbon dioxide.

As with many complicated questions, there is a correct answer to this one. But in order to determine what that answer is — beyond any doubt — we’d have to shut down all gasoline-powered engines, eliminate almost all manufacturing, halt the production of electricity, and stop burning coal. And then we’d have to wait about a century to see if carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere had dropped, average temperatures had leveled off, and ice sheets had begun to grow. Meanwhile, everyone would be dead, because despite Earth’s position in the so-called “Goldilocks Zone” (not too hot, and not too cold), nearly everyone on the planet needs some sort of shelter that includes heat or air conditioning.

Obviously, none of that is going to happen. And that takes us back to the debate. How do we settle it? I’m pretty sure we aren’t going to settle it. Both sides would have to walk away from personal gain and do what’s best for humanity. How often does that happen? Both sides would have to begin telling the truth, and stop bending and distorting information in order to bolster their own arguments. Does that ever happen? And both sides would have to actually behave in ways that reflect their words. If celebrities – especially those whose gift consists of pretending to be somebody else – want to assume the role of environmental spokesperson, they’re going to have to give up their forty-thousand-square-foot mansions and private jets. And if politicians – especially those who say one thing in front of the television cameras while stuffing their own pockets in the privacy of their offices – want to be seen as true leaders, they’re going to have to look beyond what’s best for their party and their own personal chances for re-election.

The world’s population is growing by a billion people every fifteen years or so. The city of Calgary has a million people. A population increase of a billion is like adding a thousand more cities the size of Calgary. Most of those people are going to want to own a home and drive a car and travel to other places and use whatever technology will be around then. Do we intend to tell them that they can’t? And what exactly are we willing to give up right now?

There are very few scientists in the world, and even they can’t agree on the most basic issues involved in climate change. We hear the word consensus thrown around, but we also hear claims of blackmail, death threats, lost funding, secret emails, fudged data, ruined careers, and professional ostracism. The rest of us are stuck in that huge middle chasm. We have neither the time nor the expertise to investigate and verify information, including the credentials of people who claim to be experts. We also live in a time when photographs and video can be altered and even completely fabricated, making it impossible to believe our own eyes and ears.

Is the Earth getting warmer? Probably. There isn’t a lot of stability in the universe, so I’m not sure why we would expect our climate to be any different. Are we contributing to that change? Probably. We’re here, and doing a lot of things. Can we reverse the trend? I doubt it. I’m not even convinced that things were better before. It’s true that we’re slobs, and there’s a continent of garbage floating around in the ocean. But we’ve begun to clean up our act. For example, a relatively large fraction of the world’s land has been designated as national parks, which indicates that we at least have some idea what we should be doing. Still, I wonder if we’ve over-estimated the effects of our activity. Maybe our coastal cities will be destroyed by flooding while we’re at home recycling beer cans and installing low-energy light bulbs.

Mainly, I worry that there will be rioting, and even a war, over the issue of climate change. If tempers continue to flare and each side continues to rage against the other, people will likely die and property will be ravaged. And it’s the future generations – those we all claim to be so concerned about – who will suffer the most.

]]>

In my lifetime, we have been scared out of our minds by an assortment of impending disasters: nuclear war, asteroids, asbestos, fire ants, locusts, killer bees, rogue planets, Lyme Disease, Mad Cow Disease, SARS, swine flu, bird flu, Satanic cults, holes in the ozone, the Bermuda Triangle, alien abductions, the Y2K bug, and – every couple of years — the imminent end of the world. During centuries past, humans feared comets, solar eclipses, lightning, and other natural events, as well as ghosts, witches, vampires, werewolves, zombies, and demonic possession. We are, it seems, wired to worry about something that’s out there, and that’s coming to get us.

With most of these concerns, a lack of basic scientific knowledge plays a role. So do feelings of helplessness and vulnerability. The threat appears out of the dark. It’s unpredictable and overwhelming.

As our clocks and computers ticked down the last few days of 1999, we split into two opposing camps. One side believed that in the opening seconds of the year 2000 most vital systems, especially those involving transportation, communication, and power, would cease to function. Meanwhile, the skeptics were confident that we were facing little more than temporary and scattered glitches. Nobody could be certain, but each clung tightly to their views. And then, nothing happened.

In December 2012, otherwise sane individuals spent a fortune on supplies of dried food and underground concrete living quarters. Their dread was driven by arbitrary interpretations of ancient Mayan calendars and an imagined collision with either a black hole or a non-existent planet. Once again, the cataclysm failed to arrive.

With each generation the specific emergency changes, but the general reaction follows a consistent pattern. Panic spreads, like a virus, from mouth to mouth. Entrepreneurs with exactly the right college degree begin cranking out videos, lectures, films, magazine articles, and books. They cite experts who support their premise, and denounce anyone who expresses even a hint of doubt. Breathless newscasters fan the flames night after night by repeating the message that we’re doomed. As a result, a lot of people spend a lot of money to protect themselves, while a much smaller group of people make a lot of money by fueling the distress.

And then it’s over. The emotional energy dissipates and the terror is gone, soon to be replaced by the next catastrophe lurking just over the horizon.

Today, much of our anxiety centers around climate change. The planet is heating up, the ice caps are melting, and the oceans are rising. Inhabited islands will be swallowed by the sea. Coastal cities will be flooded. Deserts will continue to expand, aggravating an already widespread famine problem. Earthquakes, tornadoes, and hurricanes will increase in number and intensity. Wildfires will destroy forests and property, kill countless animals, and send thousands of residents fleeing from their homes.

Several factors make this current situation unique. For one, the timing is uncertain. We’re not sure if we’ll be facing the crisis next year or sometime in the next decade. It’s more likely, we hear, that it will be our children and grandchildren who will suffer the most dire consequences of global warming. Worst of all, the source of the danger is not out there somewhere. It’s us. It’s our lifestyle. This time, we’re told, we aren’t powerless. Survival is a matter of choice.

If we take a step away and look at the climate change issue from a disinterested distance, that same familiar pattern is evident. Humanity has separated into two main camps. Each parades out a string of scientists, all armed with irrefutable proof in the form of data, graphs, and a clear consensus. Each forecasts unimaginable turmoil if their warnings are ignored. Each accuses its opponent of being motivated by greed, while bank accounts swell from money flowing in both directions. Even now, as you’re reading this, thousands of people are traveling to Manhattan for a massive demonstration called the People’s Climate March, scheduled for Sunday, September 21. Its marketing campaign refers to the gathering as an invitation to change everything. Of course, the other side has already contrived its response, questioning the logic of commuting to a rally: Aren’t the protestors burning a river of gasoline in order to proclaim the perils of carbon emissions?

And here we sit, the rest of us, listening to each argument in turn, our bewildered heads lurching back and forth as though we’re watching two teams playing a sport we cannot comprehend, and trying to determine just how to place our bets. In the end, the facts will be most important. But first, we have to make our way through a tangle of perceptions.

]]>

I’m seated in my car. There is another vehicle in front of mine, a Toyota Corolla with a small dent just below the left tail light. The word Corolla on the back of the other car reminds me of corona, which is the fuzzy glow around the edge of the sun. I’m pretty sure it’s also a brand of beer. There’s a Corona Park in Queens, New York, not to be confused with Crotona Park, which is in the Bronx. From there, I think of cruller, a word I learned when I worked as a baker at a doughnut shop immediately after high school graduation. I was seventeen. If I owned a doughnut franchise, would I ever hire a seventeen-year-old and place my entire business into his clumsy hands? Also, did I really go to work at five in the morning for a dollar-sixty an hour? Cruller doesn’t sound like a kind of cake. It sounds like something you dig up out of the ground, and then go around showing it to people and asking them what they think it is. The dent is high and circular, about the size of a golf ball. It doesn’t appear to be the result of a minor accident or a bump in a parking lot. Based on its shape and location, I’d guess that a short knight riding a pony in a jousting match may have rammed the Corolla with his lance. Or maybe the driver lives near a golf course. A bumper sticker just below the dent says Vote No on Plan B. If I’d had a Plan B, I’d have made a right turn out of the post office and gone around the block the other way, and I’d be home by now.

I have time to think about these things, because I’m waiting to make a left turn. The light is green, but there’s traffic coming from the opposite direction. Rather than proceed into the intersection, the driver in front of me holds back and maintains his red light position. He doesn’t budge an inch, and so neither can anyone else. I believe I was behind this same man at the bank last Tuesday afternoon. That day there were thirteen people ahead of me, and once I joined the group, no one else did, so I was always at the end of the line. For a long time I made no progress, and had resorted to shifting my weight from one foot to the other and counting the letters on the mortgage rate poster, even though three or four customers finished what they were doing and departed. The man didn’t move up when he was supposed to. He let an unnatural gap form between him and the next person in line, so that there was no intermittent release of the tension that builds when you’re trapped, motionless, and watching the clock on the wall as it ticks away at your mortality. I was going to tap him on the shoulder and ask him if he was all right. Maybe he’d slipped into a shopping mall trance, a syndrome I was familiar with. The symptoms consist of an irresistible urge to flee the premises, accompanied by a curious inability to move a muscle. I had plenty of opportunity to inquire about his condition. The elderly lady now at the front of the line was paying her electric bill with a bagful of unrolled dimes. But I was sure he’d step forward at any moment, and I didn’t want to risk getting into a conversation with him. The last time I did that, at the veterinarian’s office, I was sucked into a half-hour lecture on both the advantages and the hardships of living in Winnipeg, Manitoba. After the clock had swept away another slice of our existence, the man approached the teller window, completed his transaction, and left. And so did I.

The incident at the bank was almost forgotten, but now the memory of it has returned as I sit behind the Toyota Corolla and wonder if this is where I’m going to spend the rest of my life. There is no wall and no clock, but clouds have arrived from the distant horizon, and the blue sky everyone at the post office had marveled about has transformed into a dull gray. Off to the left, a young woman in a bright yellow vest stands in the road clutching a sign that says Slow. Obedient drivers file past her at a quarter of the speed limit, and I find myself wishing to be moving that slowly. I imagine her still standing there in the winter, her sign shaking in her frozen hand, my car and the Corolla covered with a thin layer of fresh snow. Across the street in the other direction, construction workers are busy erecting a single-family residence. Eventually, I’ll watch the new owners as they unload their rental truck, plant trees in the front yard, maybe get a dog, and raise their children. The traffic light will change – green, yellow, red, and back again – through thousands of cycles. The Corolla’s left turn signal will burn out and stop blinking, its driver considering the possibility of removing his foot from the brake pedal, but always regaining his senses at the last moment. Meanwhile in the car behind him, long out of gas and needing to trim my beard, I’ll begin contriving some sort of weapon out of plastic fast-food cutlery and twisted road maps. My plan will include hijacking his car, running the red light, and parking in the driveway of the now abandoned house across the street. I’ll leave my own rusted vehicle at the old post office building, which has been converted into a doughnut shop. I may go in and see if they need a baker, one who is mature and patient and knows how to make a left turn at a traffic light. But first, I have to get to the bank. My electric bill is way overdue.

]]> I watch a lot of movies. There was a time when I thought I’d be in movies, but I’m past that now, just as I’m pretty sure I’m never going to walk on the Moon or play centerfield for the Yankees. Acting looks like fun, and pays well, too, but then I found out that you have to go to auditions. The first time I sat at a table and tried to sell things at a flea market, I discovered that I have a low threshold for rejection. I quickly reach that point where I’m tempted to grab people by the throat and demand to know what they’re looking for. That wouldn’t be a helpful reputation, I suspect. Word would soon spread that I’m a temperamental artist who’s hard to work with, and there goes my career.

I watch a lot of movies. There was a time when I thought I’d be in movies, but I’m past that now, just as I’m pretty sure I’m never going to walk on the Moon or play centerfield for the Yankees. Acting looks like fun, and pays well, too, but then I found out that you have to go to auditions. The first time I sat at a table and tried to sell things at a flea market, I discovered that I have a low threshold for rejection. I quickly reach that point where I’m tempted to grab people by the throat and demand to know what they’re looking for. That wouldn’t be a helpful reputation, I suspect. Word would soon spread that I’m a temperamental artist who’s hard to work with, and there goes my career.

Since abandoning the acting profession, I’ve settled into my new role as an audience member. The money tends to flow in the opposite direction, but at least I get to be the one who does the criticizing.

Not that my observations are harsh, or even significant. Most relate to minor details that most people would fail to notice, or choose to overlook. Here are a few.

1. It rains in every movie. It’s never a light rain, or a normal rain, either. It’s always a sudden downpour that appears to be located directly above someone’s head — or their house, if it’s an indoor shot. The drops of water are the size of small plums and threaten to dent the tops of cars. Apparently, film makers have this machine that simulates precipitation, and they’re required to use it in every movie in order to justify the investment. As far as I can tell, this is just another example of Hollywood extravagance. A garden hose would work almost as well. But heavy rain is dramatic, so the cinematic monsoons are likely to continue, and as always we’ll see very few films that take place in the desert, or on the planet Mercury.

2. There are also people smoking cigarettes in every movie. There’s usually no reason for them to light up, so you may not consciously notice it, but once you do, it’s startling to see how often it happens. I wonder if the tobacco companies are subsidizing the rain machine, and getting free commercials in return.

3. Most movies force us to read too much. I read all day, so when I sit down to watch something, I don’t want to be confronted with emails, text messages, Internet searches, and notes on crumpled scraps of paper. These fragments of information are always shown during a pivotal point in the story, and difficult to decipher on our relatively tiny television. This usually causes me to grow agitated, point to the screen, and yell out, “What did that say? Who wants to meet him where and for what?”

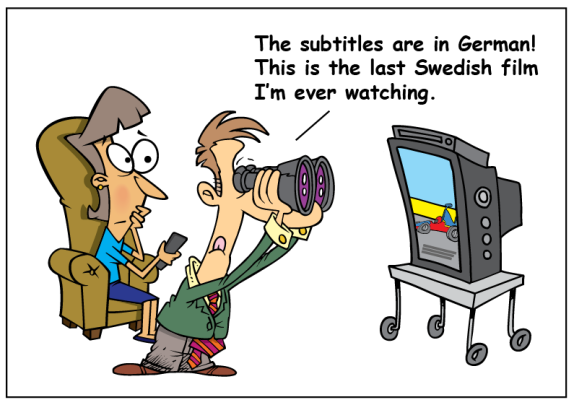

4. Subtitles are especially confounding. At the end of the film, the credits scroll up, and I see that many hundreds of people have worked on the production. There are grips and gaffers, prop supervisors and boom operators. There is a person whose job it is to load the film into the camera, and another who pulls cables around the floor of the set. These jobs are extremely specific. The hairstylist probably has his own hairstylist. I have to think that it must be someone’s responsibility to look at the subtitles and make sure they’re readable. If dialogue is important enough to translate, it’s likely to be somewhat crucial to the plot. But apparently, when a film slips over budget, the subtitle guy is the first to go, replaced by a blindfolded court stenographer. As a result, we get white letters superimposed onto a snowstorm. We also get characters rattling away in a foreign language while the English version flies by at the bottom of the picture, causing me to lean forward and again scream, “She called her mother when and heard what about whose sister?” This isn’t a major problem at home, where the rewind and pause buttons are always within reach. At the theater, however, it causes me to miss the rest of the movie because now my mind is preoccupied with formulating the indignant letters I’m planning to send to the director, the cinematographer, and the head of the production company, and maybe their hairstylists, too.

5. Chase scenes bore me beyond description. I usually find myself wishing that all the vehicles involved would slam into a wall or drive over a cliff, just so it would stop. Sometimes the chase is on foot, with people scrambling up ladders, across rooftops, and through dark alleys cluttered with barrels of trash. In most of these scenes, at least one of the people who’s driving or running is unfamiliar with the location, yet seems to know every shortcut and secret hiding place. I yell at the screen once more, but they’re all too busy dodging taxis, delivery trucks, and skidding buses to hear a word I’m saying.

6. Romantic comedies should have a running-time limit of ten minutes. This is how long it takes me to figure out who’s going to end up with whom. And believe me, I’m not exactly an insightful viewer. I had to watch The Three Stooges twice, because I missed most of the nuance the first time.

At the beginning of a romantic comedy, one of the main characters is engaged to someone who is rude, insensitive, and not a good listener. Don’t worry. They will not get married. Also, very close to the end of the film, the couple you’re hoping will be together will appear to break up and you might fear that their relationship is doomed. It isn’t. At the last possible moment, one of them will jump on a plane and go to Belgium, where the other person has been living for the past year, apparently without any social life whatsoever. They will kiss in the doorway, say something charming, and that’s the end of the story.

As the credits roll, there will be another short clip up in the corner, showing the couple now happily married with three kids and a dog. And who knows? Maybe someday my name will be among those hundreds that scroll by in a blur. I won’t be playing a main character, but more likely an astronaut or a baseball player. Or I might be the guy at the flea market, grabbing a customer by the throat. But no matter the role, I’m sure it’ll be raining really hard, and we’ll all be smoking cigarettes and sending each other important messages that you won’t be able to read. You can count on that.

]]> It was the summer of 1985. Jill and I were taking the first steps into our thirties, and while our goals were still ambitious, they were no longer earthshaking. The dream of changing the world had begun to fade, and we had started to focus on the smaller world right around us. We wanted what everyone wanted: a safe home, a healthy family, a few good friends, enough money to pay the bills, and some time to enjoy it all. Measured against those criteria, we were doing well. We’d been married for almost four years, had bought a house in Connecticut, and were soon going to have a baby.

It was the summer of 1985. Jill and I were taking the first steps into our thirties, and while our goals were still ambitious, they were no longer earthshaking. The dream of changing the world had begun to fade, and we had started to focus on the smaller world right around us. We wanted what everyone wanted: a safe home, a healthy family, a few good friends, enough money to pay the bills, and some time to enjoy it all. Measured against those criteria, we were doing well. We’d been married for almost four years, had bought a house in Connecticut, and were soon going to have a baby.

The circumstances leading up to those events, and the ordeal that followed, are the subject of a memoir I’ve recently finished. It took me nearly three decades to write The Long Hall. Not that I was working on it with anything that could be described as diligence. Mostly, I was avoiding the whole project, because it seemed like an insurmountable task to pin down the details and capture the thoughts and emotions. The truth is, I doubted that I could do it justice. The more time that slipped by, the less I wanted to go back and re-open the wounds. But it’s a story that deserves to be told, especially now that my daughter Allison is about to have a baby of her own.

The Long Hall recounts, in a series of eighty-five connected scenes, our adventures into both the mundane and the unimaginable. It’s filled with humor and heartbreak, a lot of good memories and a lot of unbearable ones, too. This excerpt is one of those scenes.

Braxton Hicks

Very close to the end of the pregnancy, we were out walking near our home. Jill had been having contractions, on and off, for days, and she thought activity would hasten things along. We went to the end of our short street, then followed a path that led to the public library. We spent about an hour looking through books and magazines, until Jill got restless and wanted to go home.

Outside, the sky had darkened and about a minute from the library, it began to rain hard. It was July, so the maple trees were thick with foliage. We noticed the ground was dry under each one, and we sprinted from tree to tree. But the rain turned into a downpour. The trees soon lost their battle with the torrent, the dry ground vanished, and we were getting drenched. About halfway home we realized there was no shelter and just ran the rest of the way, screaming and laughing — pretty much the same as we had months earlier, when we first spotted the doughnut in the plastic tube. We were soaked. We undressed just inside the front door and took a shower together. Our skin was cold from the rain, and the warm water mingled with the laughter, and with the unspoken sense that we were racing toward something that was racing toward us.

A few days later we watched the movie, The Competition, on television, then left for the hospital at eleven-fifteen. Jill’s bag was already packed because we’d been through this routine at least twice, thinking she was ready to deliver, only to find out it was false labor. When a baby is ready to arrive, the mother’s body begins a series of contractions in order to push the infant out. But prior to this process there is often a practice period, a dress rehearsal of sorts. It isn’t time to deliver, but it feels like the real thing. Women refer to these early contractions as Braxton Hicks.

“She wasn’t ready to go. She was having Braxton Hicks.”

Women are born knowing about these things. Men have to listen and learn through experience, passing through several stages of decreasing ignorance before they can comprehend what’s going on. The first time I heard of Braxton Hicks, I assumed it was the name of a medical office. Then I thought it might be some kind of rash. I rarely understand anything the first time around, but I eventually made the connection with false labor.

The key point, I guess, is that you don’t know it’s Braxton Hicks at the time. You only find out when you come home without a baby. With each false alarm, it seems more and more as though the real thing will never happen, even though some part of your mind knows it must. In a strange way, it was similar to watching someone endure a long terminal illness, the way I watched my father inch slowly downhill. You may think they’re about to die, then they pull back, and for a little while seem to be heading toward recovery. Each time, there is that sense of relief, because you’re never really ready. But now the contractions were closer together and felt different. I reminded Jill that she had said that before.

“It feels different,” she said.

“That’s what you said the last time.”

“But those weren’t real. This is real.”

“How do you know?”

“Because it feels different this time.”

We called the doctors’ office and the nurse told us to get to the hospital. So this was it. Here was that car ride I’d thought so much about, the one you see on television and you think, please don’t let it happen like that. I’d practiced it over and over in my mind. We’d done a trial run the week before. We’d been to the hospital for the new parents’ tour. We should’ve been ready, and we were. Everything was under control. My driving was smooth and effortless. We could have been going to the supermarket for a loaf of bread, except it was almost midnight, and you leave your house at that hour only for life-altering events.

After parking the car, I felt bothered for just a moment by the bright yellow EMERGENCY sign. I opened Jill’s door and she climbed out. Then we walked slowly through the doors of Bridgeport Hospital.

It was 11:40. The day we would have our first baby — July 12, 1985 — was itself about to be born. We were in that moment when everything changes. The bridge from here to there was twenty feet of linoleum. We stopped at the desk and answered questions. Name, address, insurance. A thin man in pale green scrubs appeared out of nowhere, steered a wheelchair up behind Jill, snapped the footrests into position, and pushed her toward the elevator. We had no way of knowing, but Jill had just walked the last twenty feet she would ever walk. Right there. That faded, scuffed stretch of hallway. She was thirty years old. I was twenty-nine. We had been on top of the world for the past four years. But the world rolls. Sometimes you roll with it, and sometimes it rolls on top of you.

I was surprised to notice that my hands were shaking. I was having one of those conversations in my head, like the one I have when I’m on an airplane that’s about to take off.

“There are thousands of flights just like this every day.”

“I know that.” (This is me talking to myself.)

“Every day of the year.”

“Yes.”

“Almost without incident.”

“True.”

“So what are you nervous about?”

“I didn’t think about those other planes. I wasn’t on them.”

“This plane will have a problem because you’re on it?”

“I should get off now and save these other passengers.”

It was the same conversation I’d had so many times while driving across bridges. Worrying that the bridge would fall actually prevented it from happening, because the coincidence of this massive structure giving way at the very moment I was thinking about it was too unlikely. Sure enough, I’d always made it safely across, along with hundreds of other drivers, all seemingly unaware that I’d just prolonged their lives.

Logic, of course, is on the side of the optimists. More than a hundred million babies are born each year. How often does something go wrong? Statistically, almost never. In only about three percent of all births, there’s a serious problem with either the mother or the baby. However, that still works out to thousands a day. We don’t hear about those incidents because they’re small and private. There’s no debris field or black box, no eighteen-wheelers doing headstands after a vertical drop. Just long hospital stays, years of struggling, quiet funerals. Newspaper headlines are reserved for airplanes slamming into mountains and bridges falling into rivers.

I followed as the attendant backed Jill into the elevator. There was something comforting about the way he shuffled his feet, and how he pushed the buttons without looking. Another night, another baby. Still, it felt like a dream, and not an entirely pleasant dream. For one thing, I was sure I’d never get used to seeing Jill in a wheelchair. For another, I hadn’t completely shaken that vision I’d been having, the one where I was in the grocery store with a newborn baby, and Jill wasn’t there. I was looking out the airplane window and could see the ground rushing up. I could feel the roadway sinking away as the bridge began to collapse. But I wasn’t sure if it was really happening, or if it was all in my head. I shuffled along with the attendant as he pushed Jill out of the elevator and into the future. I looked ahead, down the long hall, and tried to see where we were going. My heart was full, and racing. My movements, I knew, were calm and smooth, just as my driving had been between our home and the hospital. I was all right, and yet I was not all right. There was a wheel rotating inside my chest, turning to fear, then joy, then a hazy uncertainty, and back to fear. Not a panic attack, exactly, but something like it. A false panic attack. An emotional Braxton Hicks.

The Long Hall is 320 pages, and can be purchased for $12.95 from Amazon.com. The e-book edition is also available, for about $3.99 US, in any country where Amazon has a Kindle store.

If you have found any enjoyment and derived any value from this blog, I think you will like the memoir just as much. I hope so. Thank you for reading, and for helping me get the word out about this book.

]]>

My childhood was filled with peculiar sayings and expressions. I heard them so many times that I was sure they must have meant something, and equally sure that I was just too dumb to know what it was.

My childhood was filled with peculiar sayings and expressions. I heard them so many times that I was sure they must have meant something, and equally sure that I was just too dumb to know what it was.

Most of these phrases were employed by adults who, in the way of the mid-twentieth century, strove for efficiency and productivity. There was no need for a lot of creative thought or original language, because others had already done the work. As a result, understanding could be conveyed rapidly by choosing the appropriate off-the-shelf, freeze-dried idiom: simple adjectives that had been expanded into crisp, four-word similes.

Drunk as a skunk.

Naked as a jaybird.

Dry as a bone.

Dead as a doornail.

Communication was instant, like our rice and our coffee. It was effortless, like our Kodak cameras and frozen dinners. It was convenient, like our wall-mounted paper cup dispensers. And it was satisfying, like our Lucky Strike cigarettes.

The only problem, for me, was that I could never figure out what anybody was talking about.

“I’m as sick as a dog.” My father said this sometimes. The description relies on pure vagueness, and the difficulty of verification. No one can ever know how sick a dog feels, but we can imagine. Dogs are constantly sticking their faces where faces shouldn’t go, eating things off the ground, and going outside in the middle of winter without a jacket or gloves. A patient mentions this to a doctor — that he feels sick as a dog — and nothing more needs to be said. The doctor, in turn, is armed with a ready response. “Take one of these pills twice a day. In no time, you’ll be fit as a fiddle.” The doctor, of course, can sense that the person has never gone to medical school, and probably doesn’t know much about music, either. To the untrained ear, the prospect of acquiring the health status of a finely tuned instrument sounds appealing. Also alliteration always cranks up the effectiveness by a notch or two. Fit as a tuba wouldn’t have the same bounce.

My father said this sometimes. The description relies on pure vagueness, and the difficulty of verification. No one can ever know how sick a dog feels, but we can imagine. Dogs are constantly sticking their faces where faces shouldn’t go, eating things off the ground, and going outside in the middle of winter without a jacket or gloves. A patient mentions this to a doctor — that he feels sick as a dog — and nothing more needs to be said. The doctor, in turn, is armed with a ready response. “Take one of these pills twice a day. In no time, you’ll be fit as a fiddle.” The doctor, of course, can sense that the person has never gone to medical school, and probably doesn’t know much about music, either. To the untrained ear, the prospect of acquiring the health status of a finely tuned instrument sounds appealing. Also alliteration always cranks up the effectiveness by a notch or two. Fit as a tuba wouldn’t have the same bounce.

“She’s as cute as a button.” I think this was made up, on the spot, by someone who needed to say something positive about a friend’s baby, but also didn’t want to lie. There are thousands of different buttons, so the statement is meaningless. It’s like saying, “She’s as interesting as a documentary.”

“She’s as cute as a button.” I think this was made up, on the spot, by someone who needed to say something positive about a friend’s baby, but also didn’t want to lie. There are thousands of different buttons, so the statement is meaningless. It’s like saying, “She’s as interesting as a documentary.”

“He’s as happy as a clam.” This one was especially perplexing. Clams live buried in the mud, feeding mostly on particles of dead fish. Eventually, a person will come along and dig the clams up with a shovel, throw them onto a barbecue grill or into a pot of boiling water, then crack open their shells and eat them. Whenever I heard someone say it, I had to go find a dictionary and look up the word happy.

“When you’re finished washing the car, I want it to be as clean as a whistle.” My uncle actually said this to my cousin and me one day in the early 1960s. He was probably paying us twenty-five cents each, so he wanted to make sure he got his money’s worth. We assumed he meant that the car should be clean enough to put in our mouths, although that only added to our uncertainty. I don’t remember, but he may have also insisted that the interior be neat as a pin.

“He looked as proud as a peacock.” I suspect we’re way off on this one, too. We can’t claim to comprehend the internal life or mental state of any large bird. Specifically, we’ve learned little about a peacock’s ability to experience pride. Many could very well have real self-esteem issues, including deep-seated insecurities and inferiority complexes. Yes, most peacocks have nice feathers, but looks fade. And then what?

“We were all pleased as punch.” Being culturally illiterate, I was totally confused by the punch reference. If we don’t know how happy a clam is feeling or how sick a dog is, what can we possibly infer about the emotional state of a bowl of chilled fruit juice?

My mother was the most proficient at the use of these expressions. She described things as being clear as a bell and easy as pie, and people as cool as a cucumber, old as the hills, and slow as molasses. My little brain took it all in and stored it away. But in truth, I was as baffled as a buffalo.

I made that last one up myself.

]]>

“You’re just too cool.”

That’s what she said. In fact, those were her exact words, which proves one thing: she’s never met me.

No one has ever described me as cool, or any heat level, for that matter. If there were a television show called World’s Least Cool Human Being, I would be the permanent guest host. When I enter a room, even the goldfish pretend they’re asleep. In high school, I was voted “Most Likely to Be Forgotten, and Well Before the Five-Year Reunion.”

It was a great surprise, then, when a fellow blogger paid me a compliment by suggesting that I was too cool. At least I think it was a compliment. The word too snagged on my brain for a moment. I’ve been told I’m too sensitive, which is a polite way of saying, “Oh, grow some skin, will you please?” And others have said I think too much, which really means, “Please shut up now and at least try to be normal.”

So her comment did get me speculating about the general concept. Can a person be too cool, and if so, where exactly is the boundary? Is it possible to just brush up against the limit without stepping over it?

Before we can talk about coolness, we have to define it, and there’s part of the problem. It’s hard to analyze something that’s cool without warming it up to room temperature first. It’s like explaining a joke – you kill the humor in the process. Or pulling that goldfish out of the water in order to explain how it lives – as my ninth-grade biology teacher did. While she pointed out the gill structures, the thing was drowning in mid-air. We can’t say for sure what coolness is, but we know it when we see it. For anyone growing up in the early sixties, this guy was cool.

Like any other personality trait, coolness is also relative. The description requires comparison and context, in much the same way that height does. A man who’s six-foot-six and working at the bakery is tall; if the same guy were a professional basketball player, he’d be average. Seated in your dentist’s waiting room, an old magazine about soybeans might seem like the most boring thing you can imagine. But if you were floundering in solitary confinement in a Bulgarian prison and stumbled upon that same magazine buried in the dirt floor of your grimy cell, you’d read it cover to cover. Even the operating instructions for a toaster oven would seem cool.

In 1986, Huey Lewis told us that it’s actually hip to be square. I’ve been pondering this idea ever since. Is it true? It’s easy to be hip when you’re on stage in Las Vegas, with flashing lights and saxophone players and five thousand screaming fans in the audience. But could my squareness be hip?

I never thought so. Until about an hour ago, I believed the scale on which we measure a person’s coolness was graduated and straight, like a timeline or a thermometer. However, this does little to clear up the issue. What’s the opposite of Cool? Is it Lukewarm? Tepid, maybe? More complications: Beyond Cool would be Cold, which is a completely different thing. And at the other end, past Tepid, would be Hot, which also has its own meaning.

In a flash of insight that was as notable for its intensity as much as its rarity, I saw that the scale was not a straight line at all, but a circle. This is why, when you don’t even know – or care – how uncool you are, that very tendency is itself considered cool. It’s something like an honorary degree. When people drop out of college in their freshman year to pursue careers that have nothing to do with learning or knowledge, and go on to become incredibly wealthy and powerful, terrorizing their own employees along the way and demonstrating that our system of education is somewhat useless, universities reward them with a diploma and let them wear a cap and gown and give a speech to the real students. Naturally, this got me wondering about the recipients of those honorary degrees. They didn’t pass any courses or write any dissertations. Do they frame the piece of paper and hang it on the wall anyway? If not, what is it for? My uncle used to give me two-dollar bills on my birthday. Before I could even fold the cash and put it into my pocket, my father would tell me that I should never spend it.

“Two-dollar bills are rare,” he’d say. “Don’t go buying comic books with them.” But if I couldn’t spend it, I thought, it wasn’t really money. The worst part is, this was the only piece of financial advice anyone has ever given me.

In the 1970s, the cool handshake knocked me farther out of sync. This was the vertical-clasp, let’s-go-smoke-some-weed handshake. I never adopted that greeting, and it always led to a lot of awkward fumbling in the air, which preceded a maddening conversation that would usually begin with my saying, “Sorry, I don’t smoke weed. Do you have root beer?”

I didn’t say far out or groovy or dig this. I didn’t call my house a crib or refer to my car as wheels. The expression right on! was popular for a few years, and it seems to have made a comeback of late. I never even used it the first time around. I’ve said those words, but only when embedded in longer sentences:

“You can turn right on red here.”

“Keep right on kicking me in the leg, and see what happens.”

“You were right on Tuesday when you said that wall was going to fall down.”

I’ve never been on a motorcycle, or worn a leather jacket. I’ve never smoked a cigarette or gotten stoned or hitchhiked anywhere. I can’t tell you a single detail about any member of any rock band. And when I’m at the convenience store, I see magazine covers featuring pictures of famous people, and I have no idea who they are.

I’ve never said Bring it on to anyone, or the more recent shortened version, Bring it. When the expression gets reduced to just Bring, I probably won’t say that, either. I’ve also never asked What’s going down? or referred to sunglasses as shades or called anyone Bro or Dude. I’ve never said It’s all good or No worries, mostly because it isn’t all good, and I can think of a billion things to worry about.

On the other hand, lately I’ve been rolling up the sleeves of my tee shirts, the way teenagers did in the fifties. I’m not trying to re-create a trend, though — it’s just been kind of warm in the house. I’ve also taken to wetting my hair and slicking it back, but that’s only because it’s starting to grow in strange directions. Sometimes I resemble one of those nuclear physicists who hasn’t left the laboratory in six months. Other than that, I don’t really care what I look like or what anyone says. Even friendly fellow bloggers. And I guess you know what that makes me.

I invite you to listen to this song once, then spend the rest of the weekend trying to get it out of your head.

]]>

Here’s a thing I’ve noticed. It has to do with accents, but the theory can be applied to a lot of other things, as well: The farther away we are from a place, the more everything seems to look and sound the same.

Here’s a thing I’ve noticed. It has to do with accents, but the theory can be applied to a lot of other things, as well: The farther away we are from a place, the more everything seems to look and sound the same.

I’ll give you an example, because so far you have no idea what I’m talking about.

In the United States, everyone below Iowa and east of New Mexico speaks with what is generally referred to as a southern accent. Whether you’re from Cleveland or Calgary or Copenhagen, that’s what you hear – and it’s all you hear. Those southerners all sound alike. Don’t they?

Move in closer, though, and details emerge out of the haze. You start to discern that people from Texas don’t really talk like people from Alabama, any more than residents of Kentucky speak exactly like their neighbors in Tennessee. There are similarities, and just as many subtle differences. In fact, the more you listen, the more you realize that it’s possible to distinguish speech patterns from within various parts of the same state. Even small towns can have their own distinct accents, but in order to hear those distinctions, you have to be near the action. You also have to pay attention.

What does this have to do with anything? I’m not certain, but I think failing to acknowledge this premise is one of the ingredients in a dangerous process. It begins in ignorance, winds through insensitivity, and leads inevitably to hostility, racism, and xenophobia.

All Koreans look alike. Yes, from a distance they do, just as any crowd of total strangers will seem to share only that element of strangeness. We’re too far away to recognize their unique qualities. It’s after you meet and get to know individuals that you can tell one from another. The same thing happens with planets and cows and shades of color and disco music and Girl Scouts and identical twins and men with cerebral palsy. And soldiers.

I keep coming back to accents, though, because it’s a good example of how we influence each other over time. How do local accents form? Does one person suddenly start pronouncing a word a certain way, and everyone follows along? What keeps it going, and changing? Why do people in New England drop the letter R from certain words that have them, and then insert them into words that don’t? Were those conscious decisions, or two separate tendencies that eventually converged?

Sometimes I imagine a gigantic vacuum machine that sucks all the people out of the world, blends them together in a big drum, then sprays them back out in random places. Assuming everyone now had to stay where they ended up, would the same accents return over time, or would there be all brand new ones? Out of the varied mixture, would there always be a single rhythm and pattern that would come to dominate the others?

Sometimes I imagine a gigantic vacuum machine that sucks all the people out of the world, blends them together in a big drum, then sprays them back out in random places. Assuming everyone now had to stay where they ended up, would the same accents return over time, or would there be all brand new ones? Out of the varied mixture, would there always be a single rhythm and pattern that would come to dominate the others?

When people are speaking a language we don’t understand, we can’t hear the accent at all. At least I can’t. Again, that’s because of distance, and inexperience. People from different regions of Algeria and Argentina must converse with an identifiable cadence and set of inflections, but I wouldn’t notice. To me, it’s all just Arabic and Spanish. I wonder, can people who don’t speak English notice a southern accent? Can they tell a Canadian speaker from an American? Melbourne from Manchester?

Speaking of Manchester, why do all foreign journalists have British accents? I think they’re faking. They know that if they sound British, everyone will think they’re intelligent. Maybe that’s how they got the job in the first place. I’m not even sure where that idea came from, because I’ve been to London, and they didn’t seem that smart to me. They call an apartment a flat. I’m no genius myself, but a flat is what happens to your tire when you run over a broken beer bottle. And they refer to a drugstore as a chemist. Everybody who’s ever watched cartoons must know that a chemist is a person who mixes liquids together and tries to make them explode. What does that have to do with medicine? If you have a migraine or a nervous condition, a loud bang and singed eyebrows is the last thing you need. So why a television reporter would adopt an English accent to impress us is beyond my comprehension.

One more thing. People with Irish, Scottish, and Australian accents sound normal when they sing, so they’re obviously pretending to speak that way in order to appear charming. I guess that works for a little while, but sooner or later we realize that they all talk that way, and the charm begins to fade. The fact that they all look alike doesn’t help either.

]]>

Whenever I learn something brand new – when I read a book, watch a documentary, or go on a guided tour – I eventually find myself bothered by a nagging question about the subject. It’s never the same question, but it’s usually one that undermines the entire presentation. And I always think of it too late. It could be the next day or the following week, or a decade may have passed. As I’m standing in the shower or trying to refill the stapler, a loose end of curiosity will appear inside my head, like a freshly sprouted seedling. Not a good seedling either, but a thorny weed with roots the length of a rake handle. I try to pull it out, but it keeps growing back.

Whenever I learn something brand new – when I read a book, watch a documentary, or go on a guided tour – I eventually find myself bothered by a nagging question about the subject. It’s never the same question, but it’s usually one that undermines the entire presentation. And I always think of it too late. It could be the next day or the following week, or a decade may have passed. As I’m standing in the shower or trying to refill the stapler, a loose end of curiosity will appear inside my head, like a freshly sprouted seedling. Not a good seedling either, but a thorny weed with roots the length of a rake handle. I try to pull it out, but it keeps growing back.

Here’s an example.

There’s the idea that long ago, humans wandered out of Asia and ventured into what is now the United States and Canada. According to this theory, after arriving on the new continent, they spread out slowly. Many moved south along the coast, while others headed north.

Anthropologists speculate that this began to happen about twelve thousand years ago. Or maybe fifteen thousand. Or nineteen. This is one of the advantages of being an anthropologist: you can spend all of your time speculating about things, and nobody can call you on it, because they have no idea either. Everything they know in that field is based on a few sharpened pieces of stone someone finds in the dirt, completely by accident, while they’re pouring a foundation for a parking garage.

But here’s what I don’t understand. At some point, the people who had turned northward crossed into a region that was covered with ice. There were no animals or plants, and no trees to cut down. No food and no fuel. Nothing but frozen air and frozen water. Something must have caused them to say to themselves, “This looks like a good spot! Let’s stay here!” What was it, exactly? Why didn’t they backtrack a few miles, to someplace where they didn’t have to spend every minute focused on frostbite?

The textbooks tell us that these early explorers gradually learned how to build houses out of snow, and to heat them with fire. But while they were still in the learning phase, how did they avoid freezing to death? How did they start the fires, and keep them going? What were they burning? And how did they manage to come up with a way to heat the inside of a snow house without melting the entire neighborhood?

I did try posing these questions to a museum security guard once, but he just got irritated and told me not to stand too close to the plastic igloo.

Here’s another example.

Homemade soap contains lye, which is produced when water is rinsed through a pile of ashes. Lye is corrosive. It’s used to clean ovens and unclog drains. If you dipped your hand in it, your skin would fall off. Yet, people continued to experiment with lye, reasoning that there must be a way to wash off the dirt without stripping away the flesh, too. I imagine that this pursuit of cleanliness left behind a long trail of well-scrubbed skeletons. But why this obsession with lye in the first place? Did anyone even bother to try goat’s milk?

The history books also explain that the ancient Egyptians and Greeks calculated – to a pretty high degree of accuracy – the circumference of the earth. This impresses me a lot, because I have trouble calculating how much grass seed I need for a lawn the size of a Little League outfield. They accomplished this by comparing the angle of the sun’s shadow at noon in two different cities. All it takes is some basic trigonometry, a course that, thousands of years ago, was offered as a kindergarten elective. But when you’re measuring the length of a shadow, a small error would throw off the result by a big number. They had to be sure they were working in both locations at the same moment. How did they know when it was noon in two different cities? These people were keeping time with sundials. I made a sundial in my eighth-grade ceramics class, and you couldn’t have used it to figure out what month it was.

The history books also explain that the ancient Egyptians and Greeks calculated – to a pretty high degree of accuracy – the circumference of the earth. This impresses me a lot, because I have trouble calculating how much grass seed I need for a lawn the size of a Little League outfield. They accomplished this by comparing the angle of the sun’s shadow at noon in two different cities. All it takes is some basic trigonometry, a course that, thousands of years ago, was offered as a kindergarten elective. But when you’re measuring the length of a shadow, a small error would throw off the result by a big number. They had to be sure they were working in both locations at the same moment. How did they know when it was noon in two different cities? These people were keeping time with sundials. I made a sundial in my eighth-grade ceramics class, and you couldn’t have used it to figure out what month it was.

* * * * *

I hear people talk about terrorism, and this often leads to a discussion of the Quran. The impression I get is that not one of these people has ever read a page of that book. Their intent is to ridicule it, especially the passage that allegedly promises an eternal paradise to the killers of infidels. What they most want to address is the part that says a worthy terrorist will be rewarded in heaven with seventy-two virgins.

Does the Quran really say that? I doubt it. Anything written that many centuries ago would have to be translated from one language to another, and the results are almost always unreliable. Translators are like cake decorators — they make mistakes, then cover them up with a thick layer of linguistic frosting.

I haven’t read the Quran either, so I have no idea what I’m talking about. But I can’t help but wonder about the basic premise of this particular offer. It sounds like an obvious attempt to control behavior by luring followers to do things they wouldn’t otherwise consider. There are plenty of Muslims who are at least as smart as I am, and many who are much smarter. They understand that eternity is a long time, while the concept of virginity, by definition, is temporary. How do those two ideas fit together? Then there’s the mathematical problem of needing seventy-two women for every man. And what about the virgins themselves? Do they look at this arrangement and see it as paradise, too? It seems to me they’d have a somewhat different perspective on the matter.

* * * * *

In all of these cases, and in others, the only way to clear up the mystery would be to go back in time and witness the events directly. That’s difficult to do. I attended a lecture once on time travel, but had to leave early and missed the question-and-answer period. And then, of course, it was too late.

]]>