| CARVIEW |

🙋 Why?

I don’t have analytics for this blog. I have no idea how many people read it or why they read it. As I care about backwards compatibility, a blog post is the only reliable way to communicate changes to subscribers.

🧑💻 What Changed?

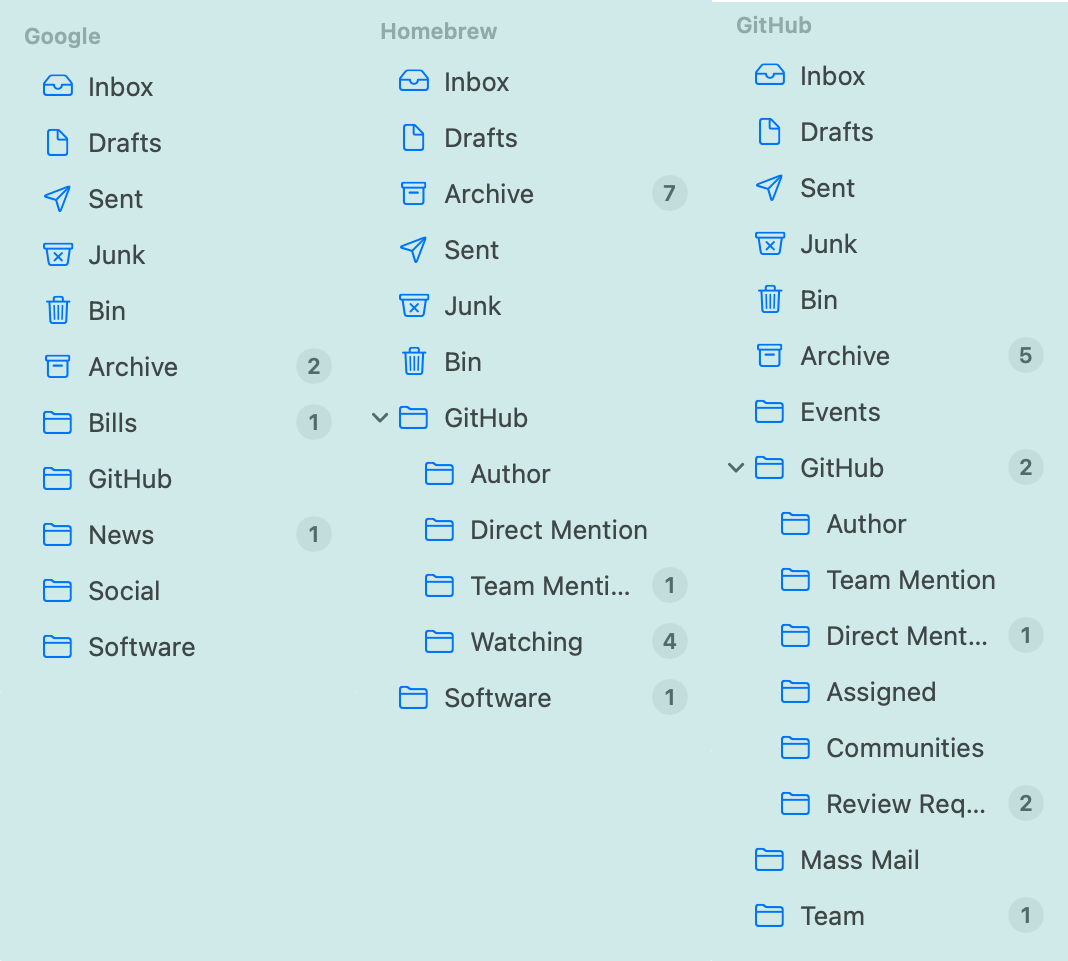

As a result of leaning more into POSSE, on this site I’ve made a few changes:

- Built my own mini Twitter/Bluesky/Mastodon/Threads equivalent called “Thoughts” at

/thoughts - Moved the homepage at

mikemcquaid.comto be all recent Articles, Thoughts, Talks and Interviews. - Added a dedicated

/articlesfor all Articles instead. - Kept the original Atom/RSS feed at

/atom.xmljust for Articles (backwards-compatibility and all that) - Added new dedicated Atom/RSS feeds:

- All Feed (all homepage content, excluding Thoughts)

- Talks Feed

- Interviews Feed

- Thoughts Feed

- Wired these up to POSSE Party and my newsletter to send relevant content elsewhere to my Twitter/Bluesky/Mastodon/Threads/email subscribers.

If you’re interested in the technical side, you can see what I did on GitHub. Given we’re in 2025, yes, I leaned pretty heavily on OpenAI Codex and ChatGPT for a lot of this. In the spirit of “vibe engineering” rather than “vibe coding”, I reviewed and edited all the code by hand.

🫵 What Do You Need To Do?

TL;DR: If you’re subscribed to /atom.xml, nothing changes.

If you want additional content: subscribe to one or more of the new feeds above.

Thanks for reading this blog ❤️. It will be 20 years old in 2026 and it’s nice to see the current blogging resurgence.

]]>The short answer is the project management triangle, commonly summarised as:

Good, fast, cheap. Choose two.

My software version is slightly different. Instead I’d say:

High quality, full scope, delivery date. Choose two.

Let’s break this down:

⭐ High Quality

This is normally the first to get compromised when engineers are pushed to “work faster”. The compromise is often silent because any bugs or declining code quality are not immediately obvious to the consumer. Constant compromise on quality results in bad software that eventually kills software companies.

Of course, the flip side is that some software engineers will endlessly polish code if given the chance. This is why “high quality” has to be the goal, not perfection.

📦 Full Scope

The “scope” of a software project is generally “how many different use cases do we build this for”. For a feature to be everything to everyone: that will take longer.

This can be seen as a “product (manager) decision” instead of a “software (engineer) decision” but it must be a negotiation. There may be things the product manager or customer added to the scope thinking they would take a day but actually take a month. With open, supportive and respectful communication, a lot of scope can often be cut and a lot of time saved.

📅 Delivery Date

Software engineers hate inflexible “deadlines”. This is because there are many hidden complexities of software estimation. Most of the time, though, organisations need to know when they can rely on some software being delivered. This becomes a problem only when there’s no wiggle room on quality or scope.

This is also why engineers pad their estimates. “Estimates” are too often treated as “deadlines”. Padding estimates actually makes a lot of sense in low trust/high stakes environments, or with a lot of uncertainty around the work. Good engineers will use the “extra time”, if they have any, to improve quality or scope.

High quality, full scope, delivery date. Choose two.

Remember and quote this when asked to deliver all three.

The only way to not have two is demanding all three (and usually ending up with one or zero).

Good luck!

]]>Most people overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in ten years.

Bill Gates wrote this in 1996 but it’s been attributed to many others before him.

Build health habits today that lead to a great body in 10 years.

Build social habits today that lead to great relationships in 10 years.

Build learning habits today that lead to great knowledge in 10 years.

Long-term thinking is a secret weapon.

“Aim to be great in 10 years”, James Clear.

I’ve lived in Scotland for 39 years. Most of my education was here; my friends and family are here too.

I’ve been friends with my best friend for 30 years. He comes around to my house weekly to watch sci-fi with me (that my wife would rather not).

I’ve been with my wife for 23 years. We have, in my opinion, a perfect marriage.

I’ve maintained Homebrew for 16 years. It’s still fun and used by millions.

I spent 10 years working for GitHub, from “engineer” to “principal engineer”. I left with lots of knowledge, friends, fun and, frankly, money.

I’ve been powerlifting for 7 years. I’m the “Scottish Masters 1” Champion (out of an admittedly small pool) and continue to improve.

That doesn’t mean sticking with everything.

I quit Christianity after 20 years when it stopped fitting my values.

I quit GitHub after 10 years when I stopped learning.

I used to practice music for hours daily and play in public weekly, but have barely played in years.

I’ve quit jobs, projects and friendships that stopped making me or those around me happy.

Long-term thinking matters, but so does quitting at the right time.

None of the above was easy. There was sadness along the way, as there is for everyone. All of it enriched my life and the lives of the people around me.

None of the above would have happened if I’d been obsessed with finding the perfect option. My choices will not be the right ones for you. I’ve been lucky, have different preferences and needs.

You could decide tomorrow to try one of the above (and you might love it). Good luck finding what your happy long time looks like, wherever you are today. I hope to see you still enjoying it 10 or 20 years from now.

]]>I think it speaks well of the gem.coop maintainers that they brought me on board given I’ve:

- never contributed to RubyGems (or even created my own gem)

- been publicly critical of André’s leadership

- previously tried to act as a neutral mediator between RubyCentral and RubyGems maintainers

Unfortunately, how things went down initially with RubyCentral signalled the need for two things:

- a written, democratic and formal governance process (to provide a clear decision-making framework)

- financial transparency (to provide accountability on where money comes from and goes to)

To help ensure decisions are community-led and finances transparent, gem.coop now has gem.coop/governance and gem.coop’s OpenCollective. I was an administrator on both to bootstrap these structures and have now stepped back.

I had planned to stay involved through the first round of community voting, but given the wider situation I felt it was best to withdraw earlier.

I remain proud of the governance work completed so far. More community-driven governance and financial transparency in open source can only be a good thing.

I wish everyone involved the best in finding a constructive path forward for, and this time with, the wider Ruby community.

]]>I’ve been working with Administrate, the world’s best Training Management System as their CTO for a few months now. When I joined, there was a similar problem: it wasn’t clear how much management was too much or too little, so I wrote an internal document. It has been lightly modified for public consumption and turned into this post.

At companies without a current need for full-time, non-coding engineering management, there is often still a need for some engineers to take on extra leadership responsibilities. It’s a hybrid of what other companies may call “Engineering Manager” and “Staff Engineer”. This role provides “minimum viable engineering management”: just enough to ensure everyone can get their job done.

The responsibilities are:

1️⃣ Regular 1:1s

You should meet each member of your team once every 1-2 weeks in a synchronous face-to-face conversation (e.g. in person, Zoom or Google Meet with cameras on) planned for 30-60 minutes. If you run out of topics to talk about: finish early. If you regularly run long: consider how you’re spending your time and plan an agenda to keep the conversation on topic. 1:1s are the cornerstone of your management.

In 1:1s you should be:

📥 Getting Context

Figure out how the person is doing in their personal life (if they wish to share anything that might affect work) and with the company.

Prompt questions:

- Learn about any potential issues outside work e.g. “How are you doing?” or “Anything I should know about going on outside of work right now?”

- “What’s going well for you at work?”

- “What’s not going so well for you at work?”

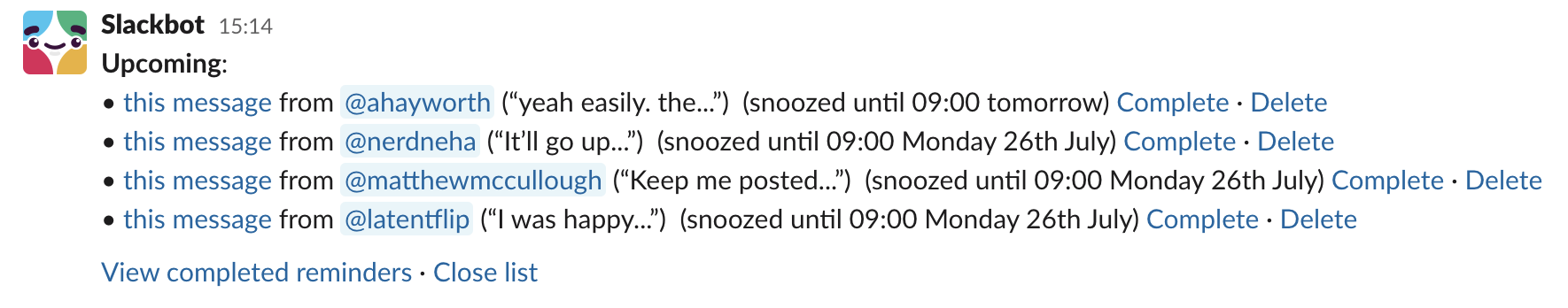

You should also gain additional context by reading async standup (Geekbot is a good tool for this) reports for your team.

📤 Providing Context

A manager is responsible for continually ensuring their team members understand what they’re doing, why they’re doing it and what is expected of them.

🎤 Delivering Feedback

1:1s are the best time to deliver non-urgent positive and critical feedback. If it’s urgent or another reason dictates giving feedback outside of 1:1s, that’s fine too; just ensure you keep consistent notes in one place. You need to regularly praise good behaviour and critique poor performance. Do not leave poor performance unaddressed just because it’s awkward to deliver. It will feel worse if you have to deliver bad news, for example about missed promotions or static compensation, due to unaddressed performance issues.

Prompt statements:

- “This week I liked that you…”

- “Last week you did…, what I would have liked to have seen was…”

Deliver positive feedback in public channels (e.g. Slack) and critical feedback privately, in a Slack DM if urgent (e.g. stopping a risky PR being merged) or in a 1:1 if not. You should consider how to deliver the feedback when making this decision. Is this something better done face-to-face, or is it something simple and easy to communicate over text?

🧈 Unblocking

From async standups (e.g. Geekbot), Slack messages and 1:1s, it’s your job as manager to spot when people are blocked and help unblock them. This may involve reviewing PRs, messaging someone on their behalf or assigning new work. Prompt question:

- “Anything you’re blocked on right now?”

📣 Receiving Feedback

1:1s are also a good time to get feedback from your team. Ensuring that feedback delivery is two-way builds trust and two-way accountability.

Prompt question:

- “Do you have any feedback for me based on our interactions this week?”

🏖️ Approving Holidays

As a manager, you’re responsible for approving holidays for your team. You are responsible for ensuring that no more than half the team is out during a normal working week. Ideally, give a week’s notice for a day off, a month for a week off and multiple months for multiple weeks off. No holiday can be for longer than 2 weeks without higher-level approval.

📝 Taking Notes

Everything discussed above should be noted in a permanent written form, for example Google Docs or an AI transcriber/note-taker (reviewed by a human for accuracy). This supports rewarding good performance and addressing poor performance.

🧑🎤 Individual Contribution

The above should take only a minority of your week. You should still have the majority of your time to spend on your own individual engineering contributions. If this is not the case: shout loudly to Mike and he will fix it.

If you’d like to help with similar problems in your organisation through my consulting business, please reach out 💌.

Thanks to Nora McKinnell, Jen Anderson (and ChatGPT5 🤖) for reviewing multiple drafts of this post.

Inspired by this post, I’ve launched a podcast and a GitHub Repository about these topics with Neha Batra, the best manager I’ve ever had in my career.

]]>🍺 Homebrew Contributions

Hi, I’m Mike McQuaid 👋. I’ve spent most of the last 13 years working on Ruby on Rails applications you may have used such as GitHub, AllTrails, Workbrew, and Strap. I’ve maintained Homebrew (mostly written in Ruby) for 16 years and have been the Project Leader since the position was created in 2019. Some of my responsibilities include assessing whether Homebrew maintainers’ contributions make them eligible for:

- retaining commit access and membership in the Homebrew GitHub organisation

- receiving the $300/month maintainer stipend (paid quarterly)

- receiving other payments, e.g. hardware grant, travel expenses to the AGM, lunch with other maintainers

This is partly a matter of security (principle of least privilege), partly a matter of responsible use of our funds and partly a matter of fair recognition, making “Homebrew maintainer” reflect those doing the actual work.

We built a command for this in Homebrew:

brew contributions.

If you’re trying it yourself to replicate these results, it uses the GitHub token from HOMEBREW_GITHUB_API_TOKEN or your keychain.

If I run it on myself for the last year, I get this output:

$ brew contributions --user=mikemcquaid --from=2024-09-24 --organisation=Homebrew --csv

mikemcquaid contributed >=100 times (merged PR author), >=100 times (approved PR reviewer), 1787 times (commit author or committer), 35 times (commit coauthor) and >=2022 times (total) after 2024-09-24.

user,repository,merged_pr_author,approved_pr_review,committer,coauthor,total

mikemcquaid,all,100,100,1787,35,2022

This means that in the last year I:

- authored >=100 merged PRs

- ✅ reviewed >=100 merged PRs

- authored (I created it) or committed (I modified/rebased/committed it) 1,787 commits

- co-authored (someone accepted my GitHub suggestion) 35 commits

Note: the >=100 or >=1000 in the output is to make things quicker and avoid hitting GitHub API rate limits.

This excludes actions like commenting on issues, which don’t require write access. Remember: principle of least privilege.

These are the core metrics that I use to evaluate whether someone is maintaining Homebrew. The tools and data are open. Also, because we use OpenCollective, the money coming into and out of Homebrew is open.

💎 RubyGems Contributions

Ok Mike, that’s a lot about Homebrew: what about RubyGems? Sorry, I’m getting to that.

Homebrew has open tooling to analyse GitHub contributions. RubyGems has a GitHub organisation. Let’s combine the two.

First, who are the owners, maintainers, contributors and members of the RubyGems organisation?

It’s not an easy question to answer, so I’ve built a list based on the people who either participated or were CCd by indirect on the

Proposal for RubyGems Organizational Governance.

I’ve also included the current members of the RubyGems organisation

Let’s look at contributions for the year preceding the removals:

$ brew contributions --csv --from 2024-08-18 --org=rubygems --user=aellispierce,amatsuda,andremedeiros,arthurnn,arunagw,bai,bronzdoc,colby-swandale,deivid-rodriguez,djberg96,drbrain,duckinator,dwradcliffe,ecnelises,evanphx,farukaydin,hsbt,indirect,jenshenny,ktheory,landongrindheim,lauragift21,luislavena,martinemde,mensfeld,mghaught,olleolleolle,qrush,segiddins,sferik,simi,skottler,sonalkr132

...

| User | Merged PRs | Approved PRs | Commits | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| deivid-rodriguez | 100 | 13 | 1303 | 1416 |

| hsbt | 57 | 3 | 379 | 439 |

| simi | 36 | 100 | 254 | 390 |

| segiddins | 93 | 77 | 194 | 364 |

| colby-swandale | 45 | 55 | 77 | 177 |

| martinemde | 49 | 59 | 64 | 172 |

| landongrindheim | 48 | 55 | 54 | 157 |

| lauragift21 | 14 | 4 | 32 | 50 |

| duckinator | 12 | 0 | 36 | 48 |

| olleolleolle | 2 | 18 | 7 | 27 |

| mghaught | 7 | 8 | 12 | 27 |

| indirect | 1 | 7 | 3 | 11 |

| qrush | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| mensfeld | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ktheory | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| luislavena | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| sferik | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| skottler | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| sonalkr132 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| jenshenny | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| farukaydin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| evanphx | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ecnelises | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| dwradcliffe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| drbrain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| djberg96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| bronzdoc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| bai | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| arunagw | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| arthurnn | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| andremedeiros | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| amatsuda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| aellispierce | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Full brew contributions Output

$ brew contributions --csv --from 2024-08-18 --org=rubygems --user=aellispierce,amatsuda,andremedeiros,arthurnn,arunagw,bai,bronzdoc,colby-swandale,deivid-rodriguez,djberg96,drbrain,duckinator,dwradcliffe,ecnelises,evanphx,farukaydin,hsbt,indirect,jenshenny,ktheory,landongrindheim,lauragift21,luislavena,martinemde,mensfeld,mghaught,olleolleolle,qrush,segiddins,sferik,simi,skottler,sonalkr132 aellispierce contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. amatsuda contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. andremedeiros contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. arthurnn contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. arunagw contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. bai contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. bronzdoc contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. colby-swandale contributed 45 times (merged PR author), 55 times (approved PR reviewer), 77 times (commit author or committer) and 177 times (total) after 2024-08-18. deivid-rodriguez contributed >=100 times (merged PR author), 13 times (approved PR reviewer), 1303 times (commit author or committer) and >=1416 times (total) after 2024-08-18. djberg96 contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. drbrain contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. duckinator contributed 12 times (merged PR author), 36 times (commit author or committer) and 48 times (total) after 2024-08-18. dwradcliffe contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. ecnelises contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. evanphx contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. farukaydin contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. hsbt contributed 57 times (merged PR author), 3 times (approved PR reviewer), 379 times (commit author or committer) and 439 times (total) after 2024-08-18. indirect contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 7 times (approved PR reviewer), 3 times (commit author or committer) and 11 times (total) after 2024-08-18. jenshenny contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. ktheory contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. landongrindheim contributed 48 times (merged PR author), 55 times (approved PR reviewer), 54 times (commit author or committer) and 157 times (total) after 2024-08-18. lauragift21 contributed 14 times (merged PR author), 4 times (approved PR reviewer), 32 times (commit author or committer) and 50 times (total) after 2024-08-18. luislavena contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. martinemde contributed 49 times (merged PR author), 59 times (approved PR reviewer), 64 times (commit author or committer) and 172 times (total) after 2024-08-18. mensfeld contributed 1 time (approved PR reviewer) and 1 time (total) after 2024-08-18. mghaught contributed 7 times (merged PR author), 8 times (approved PR reviewer), 12 times (commit author or committer) and 27 times (total) after 2024-08-18. olleolleolle contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 18 times (approved PR reviewer), 7 times (commit author or committer) and 27 times (total) after 2024-08-18. qrush contributed 1 time (approved PR reviewer), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. segiddins contributed 93 times (merged PR author), 77 times (approved PR reviewer), 194 times (commit author or committer) and 364 times (total) after 2024-08-18. sferik contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. simi contributed 36 times (merged PR author), >=100 times (approved PR reviewer), 254 times (commit author or committer) and >=390 times (total) after 2024-08-18. skottler contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. sonalkr132 contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. user,repository,merged_pr_author,approved_pr_review,committer,coauthor,total deivid-rodriguez,all,100,13,1303,0,1416 hsbt,all,57,3,379,0,439 simi,all,36,100,254,0,390 segiddins,all,93,77,194,0,364 colby-swandale,all,45,55,77,0,177 martinemde,all,49,59,64,0,172 landongrindheim,all,48,55,54,0,157 lauragift21,all,14,4,32,0,50 duckinator,all,12,0,36,0,48 olleolleolle,all,2,18,7,0,27 mghaught,all,7,8,12,0,27 indirect,all,1,7,3,0,11 qrush,all,0,1,1,0,2 mensfeld,all,0,1,0,0,1 ktheory,all,0,0,0,0,0 luislavena,all,0,0,0,0,0 sferik,all,0,0,0,0,0 skottler,all,0,0,0,0,0 sonalkr132,all,0,0,0,0,0 jenshenny,all,0,0,0,0,0 farukaydin,all,0,0,0,0,0 evanphx,all,0,0,0,0,0 ecnelises,all,0,0,0,0,0 dwradcliffe,all,0,0,0,0,0 drbrain,all,0,0,0,0,0 djberg96,all,0,0,0,0,0 bronzdoc,all,0,0,0,0,0 bai,all,0,0,0,0,0 arunagw,all,0,0,0,0,0 arthurnn,all,0,0,0,0,0 andremedeiros,all,0,0,0,0,0 amatsuda,all,0,0,0,0,0 aellispierce,all,0,0,0,0,0

The month preceding the removals:

$ brew contributions --csv --from 2025-08-18 --org=rubygems --user=aellispierce,amatsuda,andremedeiros,arthurnn,arunagw,bai,bronzdoc,colby-swandale,deivid-rodriguez,djberg96,drbrain,duckinator,

...

| User | Merged PRs | Approved PRs | Commits | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| deivid-rodriguez | 22 | 0 | 99 | 121 |

| landongrindheim | 7 | 27 | 10 | 44 |

| hsbt | 5 | 0 | 31 | 36 |

| simi | 2 | 8 | 17 | 27 |

| colby-swandale | 4 | 5 | 6 | 15 |

| martinemde | 1 | 2 | 6 | 9 |

| segiddins | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| lauragift21 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| duckinator | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| olleolleolle | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| mghaught | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| jenshenny | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ktheory | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| luislavena | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| mensfeld | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| qrush | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| sferik | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| skottler | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| sonalkr132 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| indirect | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| farukaydin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| evanphx | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ecnelises | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| dwradcliffe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| drbrain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| djberg96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| bronzdoc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| bai | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| arunagw | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| arthurnn | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| andremedeiros | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| amatsuda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| aellispierce | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Full brew contributions Output

$ brew contributions --csv --from 2025-08-18 --org=rubygems --user=aellispierce,amatsuda,andremedeiros,arthurnn,arunagw,bai,bronzdoc,colby-swandale,deivid-rodriguez,djberg96,drbrain,duckinator,dwradcliffe,ecnelises,evanphx,farukaydin,hsbt,indirect,jenshenny,ktheory,landongrindheim,lauragift21,luislavena,martinemde,mensfeld,mghaught,olleolleolle,qrush,segiddins,sferik,simi,skottler,sonalkr132 aellispierce contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. amatsuda contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. andremedeiros contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. arthurnn contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. arunagw contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. bai contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. bronzdoc contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. colby-swandale contributed 4 times (merged PR author), 5 times (approved PR reviewer), 6 times (commit author or committer) and 15 times (total) after 2025-08-18. deivid-rodriguez contributed 22 times (merged PR author), 99 times (commit author or committer) and 121 times (total) after 2025-08-18. djberg96 contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. drbrain contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. duckinator contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2025-08-18. dwradcliffe contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. ecnelises contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. evanphx contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. farukaydin contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. hsbt contributed 5 times (merged PR author), 31 times (commit author or committer) and 36 times (total) after 2025-08-18. indirect contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. jenshenny contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. ktheory contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. landongrindheim contributed 7 times (merged PR author), 27 times (approved PR reviewer), 10 times (commit author or committer) and 44 times (total) after 2025-08-18. lauragift21 contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 2 times (commit author or committer) and 3 times (total) after 2025-08-18. luislavena contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. martinemde contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 2 times (approved PR reviewer), 6 times (commit author or committer) and 9 times (total) after 2025-08-18. mensfeld contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. mghaught contributed 1 time (commit author or committer) and 1 time (total) after 2025-08-18. olleolleolle contributed 1 time (commit author or committer) and 1 time (total) after 2025-08-18. qrush contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. segiddins contributed 4 times (approved PR reviewer), 2 times (commit author or committer) and 6 times (total) after 2025-08-18. sferik contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. simi contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 8 times (approved PR reviewer), 17 times (commit author or committer) and 27 times (total) after 2025-08-18. skottler contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. sonalkr132 contributed 0 times (total) after 2025-08-18. user,repository,merged_pr_author,approved_pr_review,committer,coauthor,total deivid-rodriguez,all,22,0,99,0,121 landongrindheim,all,7,27,10,0,44 hsbt,all,5,0,31,0,36 simi,all,2,8,17,0,27 colby-swandale,all,4,5,6,0,15 martinemde,all,1,2,6,0,9 segiddins,all,0,4,2,0,6 lauragift21,all,1,0,2,0,3 duckinator,all,1,0,1,0,2 olleolleolle,all,0,0,1,0,1 mghaught,all,0,0,1,0,1 jenshenny,all,0,0,0,0,0 ktheory,all,0,0,0,0,0 luislavena,all,0,0,0,0,0 mensfeld,all,0,0,0,0,0 qrush,all,0,0,0,0,0 sferik,all,0,0,0,0,0 skottler,all,0,0,0,0,0 sonalkr132,all,0,0,0,0,0 indirect,all,0,0,0,0,0 farukaydin,all,0,0,0,0,0 evanphx,all,0,0,0,0,0 ecnelises,all,0,0,0,0,0 dwradcliffe,all,0,0,0,0,0 drbrain,all,0,0,0,0,0 djberg96,all,0,0,0,0,0 bronzdoc,all,0,0,0,0,0 bai,all,0,0,0,0,0 arunagw,all,0,0,0,0,0 arthurnn,all,0,0,0,0,0 andremedeiros,all,0,0,0,0,0 amatsuda,all,0,0,0,0,0 aellispierce,all,0,0,0,0,0

Added on request of Nate Berkopec: all the contributors to rubygems/rubygems in the last ~1.5 years for the same timescales as above:

$ brew contributions --csv --from 2024-08-18 --org=rubygems --user=deivid-rodriguez,hsbt,segiddins,martinemde,simi,duckinator,nobu,tangrufus,Edouard-chin,voxik,soda92,technicalpickles,jenshenny,jeromedalbert,ccutrer,nevinera,indirect,tenderlove,Maumagnaguagno,MSP-Greg,ntkme,mame,byroot,composerinteralia,flavorjones,johnnyshields,olleolleolle,jeremyevans,amatsuda,ko1,junaruga,kddnewton,koic,rhenium,larskanis,ntl,matsadler

...

| User | Merged PRs | Approved PRs | Commits | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| deivid-rodriguez | 100 | 13 | 1303 | 1416 |

| hsbt | 58 | 4 | 392 | 454 |

| simi | 37 | 100 | 255 | 392 |

| segiddins | 93 | 77 | 194 | 364 |

| martinemde | 49 | 59 | 64 | 172 |

| duckinator | 12 | 0 | 36 | 48 |

| olleolleolle | 2 | 18 | 7 | 27 |

| Edouard-chin | 7 | 0 | 20 | 27 |

| soda92 | 10 | 0 | 16 | 26 |

| tangrufus | 2 | 0 | 21 | 23 |

| jeromedalbert | 6 | 0 | 7 | 13 |

| tenderlove | 6 | 0 | 6 | 12 |

| nobu | 2 | 0 | 9 | 11 |

| indirect | 1 | 7 | 3 | 11 |

| technicalpickles | 2 | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| composerinteralia | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| MSP-Greg | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| jeremyevans | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| johnnyshields | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| rhenium | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| mame | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ntkme | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| larskanis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ntl | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ccutrer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| voxik | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| koic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| matsadler | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| kddnewton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| junaruga | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ko1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| amatsuda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| flavorjones | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| byroot | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maumagnaguagno | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nevinera | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| jenshenny | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Full brew contributions Output

$ brew contributions --csv --from 2024-08-18 --org=rubygems --user=deivid-rodriguez,hsbt,segiddins,martinemde,simi,duckinator,nobu,tangrufus,Edouard-chin,voxik,soda92,technicalpickles,jenshenny,jeromedalbert,ccutrer,nevinera,indirect,tenderlove,Maumagnaguagno,MSP-Greg,ntkme,mame,byroot,composerinteralia,flavorjones,johnnyshields,olleolleolle,jeremyevans,amatsuda,ko1,junaruga,kddnewton,koic,rhenium,larskanis,ntl,matsadler deivid-rodriguez contributed >=100 times (merged PR author), 13 times (approved PR reviewer), 1303 times (commit author or committer) and >=1416 times (total) after 2024-08-18. hsbt contributed 58 times (merged PR author), 4 times (approved PR reviewer), 392 times (commit author or committer) and 454 times (total) after 2024-08-18. segiddins contributed 93 times (merged PR author), 77 times (approved PR reviewer), 194 times (commit author or committer) and 364 times (total) after 2024-08-18. martinemde contributed 49 times (merged PR author), 59 times (approved PR reviewer), 64 times (commit author or committer) and 172 times (total) after 2024-08-18. simi contributed 37 times (merged PR author), >=100 times (approved PR reviewer), 255 times (commit author or committer) and >=392 times (total) after 2024-08-18. duckinator contributed 12 times (merged PR author), 36 times (commit author or committer) and 48 times (total) after 2024-08-18. nobu contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 9 times (commit author or committer) and 11 times (total) after 2024-08-18. tangrufus contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 21 times (commit author or committer) and 23 times (total) after 2024-08-18. Edouard-chin contributed 7 times (merged PR author), 20 times (commit author or committer) and 27 times (total) after 2024-08-18. voxik contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. soda92 contributed 10 times (merged PR author), 16 times (commit author or committer) and 26 times (total) after 2024-08-18. technicalpickles contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 6 times (commit author or committer) and 8 times (total) after 2024-08-18. jenshenny contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. jeromedalbert contributed 6 times (merged PR author), 7 times (commit author or committer) and 13 times (total) after 2024-08-18. ccutrer contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. nevinera contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. indirect contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 7 times (approved PR reviewer), 3 times (commit author or committer) and 11 times (total) after 2024-08-18. tenderlove contributed 6 times (merged PR author), 6 times (commit author or committer) and 12 times (total) after 2024-08-18. Maumagnaguagno contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. MSP-Greg contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 2 times (commit author or committer) and 4 times (total) after 2024-08-18. ntkme contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. mame contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. byroot contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. composerinteralia contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 2 times (commit author or committer) and 4 times (total) after 2024-08-18. flavorjones contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. johnnyshields contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. olleolleolle contributed 2 times (merged PR author), 18 times (approved PR reviewer), 7 times (commit author or committer) and 27 times (total) after 2024-08-18. jeremyevans contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. amatsuda contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. ko1 contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. junaruga contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. kddnewton contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. koic contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. rhenium contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. larskanis contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. ntl contributed 1 time (merged PR author), 1 time (commit author or committer) and 2 times (total) after 2024-08-18. matsadler contributed 0 times (total) after 2024-08-18. user,repository,merged_pr_author,approved_pr_review,committer,coauthor,total deivid-rodriguez,all,100,13,1303,0,1416 hsbt,all,58,4,392,0,454 simi,all,37,100,255,0,392 segiddins,all,93,77,194,0,364 martinemde,all,49,59,64,0,172 duckinator,all,12,0,36,0,48 olleolleolle,all,2,18,7,0,27 Edouard-chin,all,7,0,20,0,27 soda92,all,10,0,16,0,26 tangrufus,all,2,0,21,0,23 jeromedalbert,all,6,0,7,0,13 tenderlove,all,6,0,6,0,12 nobu,all,2,0,9,0,11 indirect,all,1,7,3,0,11 technicalpickles,all,2,0,6,0,8 composerinteralia,all,2,0,2,0,4 MSP-Greg,all,2,0,2,0,4 jeremyevans,all,1,0,1,0,2 johnnyshields,all,1,0,1,0,2 rhenium,all,1,0,1,0,2 mame,all,1,0,1,0,2 ntkme,all,1,0,1,0,2 larskanis,all,1,0,1,0,2 ntl,all,1,0,1,0,2 ccutrer,all,1,0,1,0,2 voxik,all,1,0,1,0,2 koic,all,0,0,0,0,0 matsadler,all,0,0,0,0,0 kddnewton,all,0,0,0,0,0 junaruga,all,0,0,0,0,0 ko1,all,0,0,0,0,0 amatsuda,all,0,0,0,0,0 flavorjones,all,0,0,0,0,0 byroot,all,0,0,0,0,0 Maumagnaguagno,all,0,0,0,0,0 nevinera,all,0,0,0,0,0 jenshenny,all,0,0,0,0,0

I’m not going to make any value judgements about these data. Remember that open source maintainers owe you nothing.

My only observation is that, if I were deciding based on the principle of least privilege for access control in the Homebrew organisation, based only on this data and our process, there would be people in all the groups of:

- appear they should have been removed, were removed

- appear they should have been removed, were not removed

- appear they should not have been removed, were removed

- appear they should not have been removed, were not removed

As Homebrew’s Governance has been cited as a good basis, I “stress tested” it here. I wanted to contribute data to a conversation that currently lacks it. That’s not to say who should or shouldn’t be in the RubyGems or any other GitHub organisation.

I wish we had data like Homebrew’s OpenCollective budget to similarly analyse finances, but it doesn’t seem to be public.

This situation also highlights how funding and transparency can shape open source dynamics. I’ve long believed that money is not the solution to every problem in open source. In some cases, it can create problems that wouldn’t exist otherwise.

]]>

🎨 Background

I’ve been in open source for 20 years and in tech professionally since 2007. My primary languages evolved from Java to C++ to Ruby, with production work in many others along the way. Across the years and these various ecosystems, I’ve seen many different ways of building software. Some ecosystems lean heavily into static checking, types and linting. Others rely on high levels of test coverage, pairing or microservices. While these approaches seem disparate, at various times, each has been championed as “The One True Path” to perfect software.

Modern LLMs, however, are perhaps the first technological shift in my entire career that truly feels likely to change everything.

🐣 Early LLMs

My first experience with LLMs was reviewing an early, internal alpha of GitHub Copilot for VS Code. At GitHub, I was often tapped for such reviews, largely due to my dual role as an active open-source maintainer and an internal feature contributor. Probably most importantly, though: even when it was politically inadvisable to say something was total shit: I would give that feedback were it the case.

I was very quickly and pleasantly surprised by GitHub Copilot. When I used Eclipse for writing Java in the ~2005-7 era, it was joked that you could “Ctrl-Space your code into existence”. Given the hellish amount of boilerplate Java required in those days, that was much appreciated. Copilot finally offered that same magic for Ruby: a decent autocompletion engine, something I hadn’t found across many Ruby IDEs or plugins. It immediately felt like it was saving me a bunch of typing and reminding me of APIs that I had forgotten.

The obvious downside of this early Copilot and ChatGPT 3 era was the regularity and sometimes subtlety of its hallucinations. If you carefully reviewed everything it spat out, this wasn’t a big problem. I still found it to be faster than doing things entirely manually and missed Copilot in environments where I couldn’t use it. At this stage, ChatGPT felt more like a toy; I didn’t trust its output over Google, and it couldn’t provide (non-hallucinated) citations for verification.

Digging In

By the time ChatGPT 4 was rolling out, I was still a regular GitHub Copilot in VSCode user but had been mostly ignoring other AI developments. I’m always keen to stay up-to-date and started hearing more engineers I respected finding value in these tools. I decided to dive in: paying for ChatGPT, trying (and then paying for) Cursor, and defaulting to ChatGPT over Google.

Fast forward to 2025: paid-tier LLM hallucination rates are dramatically lower. Genuinely useful agents are emerging, and I can now leverage citations to “trust but verify” LLM output effectively. I now rarely use Google, defaulting to ChatGPT, especially for deep dives into niche technical topics.

🧐 Philosophy

There’s a wide array in the degree of trust people give to LLMs. Some argue that any possibility of hallucination renders them unworthy of attention. Others “vibe-code” entire applications without reviewing any of the generated code.

The analogy that has resonated with me comes from open source: the “first time contributor”. It’s fairly common on a project like Homebrew that you’ll get a non-trivial pull request from someone you’ve never seen on the project before. This contributor might have no prior open-source activity, no GitHub bio, or even an avatar. How do you assess the trustworthiness of such a person’s pull request? By thoroughly reading, discussing, linting, and testing the code as required.

LLM code (or, to a lesser extent, prose) output is similar. It might be absolutely perfect the first time. It might be irredeemably terrible or wrong. The only way to find out is to review the output.

Open-source maintainers, especially on projects like Homebrew, have honed the skill of rapidly reviewing large volumes of unfamiliar or newly contributed code. This skill is useful, perhaps even essential, for effectively leveraging LLM output. I suspect at least some of the loud LLM skeptics are actually just very poor at code review and have no interest or desire to get better. AI code review tools (e.g. Copilot, CodeRabbit) are good companions to human code reviewers, particularly for pedantry, but not replacements.

Similar to managing open-source contributions, a few strategies can optimise both human and LLM-generated work.

First, consider giving up when it’s clear the amount of back-and-forth is actually slower than you just manually doing it yourself.

Second, heavily leverage linting, testing, and other automated tooling to establish robust guardrails.

With LLM agents, you can even instruct them to self-verify their output by executing relevant commands or tests.

For example, when working on Homebrew, I’ll ask agents to run brew style (for RuboCop code linting), brew typecheck (for static type checking) and brew tests (for unit tests) to automatically verify behaviour.

📵 LLM Modes

Based on these learnings, I’ve developed a few distinct “LLM modes” in my workflow:

- Constantly: I’m writing code, my editor of choice (Cursor, today) is just providing a nice autocomplete and quick, inline lookup for stuff I’ve forgotten.

- Regularly: I’m blocked and would normally be Googling or looking at Stack Overflow for a solution. Instead, I’ll now ask the LLM in my editor or ChatGPT for a solution or ideas. This excels at rapidly deciphering confusing error messages or sifting through large log dumps to pinpoint the source of issues.

- Rarely: I get the LLM to generate a large amount of boring and fairly trivial code based on a lot of initial research I’ve done.

An example would be in the MCP Server for Homebrew where I got Cursor to generate a first pass for a couple of methods.

I then edited this extensively and made it look and work how I wanted through manual edits and LLM refactoring.

After this, I used it to similarly generate most of the first versions of the unit tests to hit decent code coverage.

Throughout this process, I maintain frequent local

gitcommits, enabling me to usegit difffor careful review of each generated change. - Rarest: I haven’t decided how I want something to work yet, so I get LLM to generate all of the code, don’t even look at the code and repeatedly change prompts based on the generated UI or CLI output. Once the functionality is achieved, I then step away, and the following day, conduct a thorough line-by-line review and editing pass. This was similar to the writing workflow I took when writing Git in Practice where I’d write until I hit a page count without reading things back and then do an edit pass the next day. Similarly to writing, there’s limit as to how much code you can effectively review like this so you need to avoid things ballooning out of control.

I would say I do 1) hourly, 2) daily, 3) weekly and 4) monthly at this point. This pattern emerged from a continuous assessment of what maximises my personal and team productivity, balancing rapid development while minimising bugs for users.

🪩 Reflection

I’ve found LLM tooling like Cursor and ChatGPT to be an essential part of my workflow. Depending on the task, I’d say they provide anywhere between a 1% to 100% speedup. For me, ChatGPT has replaced 99% of my prior Google usage.

I’m genuinely curious to see what the future holds for LLMs. I suspect with AI hype, we’re seeing a certain amount of the Gell-Mann amnesia effect i.e. people find AI the most impressive when performing tasks they are the least familiar with. Similarly, as much as people talk about “exponential progress” with AI and imminent AGI (whatever that means today), it’s feeling more like asymptotic progress on the underlying technology. I expect the remaining large user-facing improvements of this generation of AI to be primarily be around UI and UX. The belief that we’ll “any day now” achieve deterministic results from fundamentally stochastic systems seems to stem from either a technological misunderstanding or wishful thinking.

All that said, I’d rather hire someone today who overuses LLM tooling over someone who refuses to use any. Ultimately, as technologists in a for-profit company within a capitalist economy, we are hired to generate business value. LLM tools allow businesses to do more (features, tests, automation, etc.) with less (employees, hours, budget). Lean into that. The LLMs aren’t going to take your software job, but they will let you be better at it.

Many promising engineers end up descending into masturbatory levels of obsession with how code looks rather than how value is generated. Ultimately, the business may decide it wants a shitty, vibe-coded app tomorrow rather than your perfect code in 6 months. Yes, ChatGPT may generate “junior engineer”-level code, but it’s also a wee bit cheaper than any junior engineer I’ve found.

The optimal path in 2025 is to embrace LLM tools, balancing pragmatic optimism with healthy skepticism regarding dramatic claims from either side. Build your app with guardrails to protect both human and AIs from stupid mistakes.

Let’s build some cool shit (and faster than we could in 2020). I’ve helped companies dramatically boost developer velocity and PR throughput (e.g. by 40%) through smart automation and AI integration. If you’re looking to optimise your team’s workflow in the LLM era, email me and let’s talk.

Thanks to Luke Hefson, Justin Searls, Gemini 2.5 Flash and ChatGPT o3 (I also tried but didn’t like the feedback from ChatGPT 4.5, ChatGPT 4o and Claude Sonnet 4) for reviewing drafts of this post.

]]>🎨 Background

I had designed the initial engineering hiring process at Mendeley and interviewed the first ~5 engineers there. At GitHub, I was involved in screening, interviewing and tweaking hiring processes for around ~50 engineers. Through these processes, and being interviewed myself ~15 times for engineering jobs over the years, I had a pretty good idea of what I loved and hated.

What I’d loved:

-

💕 Pairing on real code. Shout-out to AllTrails for my first interview where we actually paired together on a real bug in the Rails codebase I’d be working on. Felt the best representation of my actual skills in an interview setting, nerves aside.

-

🩳 Short, predictable interview processes. At Mendeley, as first employee, I went from having never heard of them to being interviewed and accepting an offer in a week. Huge companies can’t do this. Startups can (if they can be bothered). No-one wants to wait three months to find out if they got the job.

-

🔓 Valuing my open-source contributions. I’ve maintained a very widely used open-source project when interviewing for my last 3 gigs. If you think I’ve done a good job doing this, it’s appreciated when your interview process reflects this.

What I’d hated:

-

📚 Factual recall or gotcha questions. Don’t ask me anything I can trivially get the answer from Google or ChatGPT. It’s a waste of everyone’s time for me to just memorise a bunch of facts for your interview. If you have to look up the answers to your own interview questions for a job you’re not in the process of being fired from: you’re doing it wrong. Even if I don’t know today: I can probably learn it on the job. Relatedly, requiring specific technology experience for senior+ engineers

-

📟 Not considering relevant prior experience. Moving back from marketing to engineering in GitHub I was put through the external senior engineer interview loop. I failed. This was after shipping the “archive repository” feature while still in the marketing organisation (almost) single-handedly. A few months later, I was moved over anyway to work on GitHub Sponsors. One year later, I was a staff engineer. Three years later, I was a principal engineer.

-

🙋 Assuming one-way interview. I’ve had several interviews who clearly took pleasure in seeing people squirm when jumping through hoops. They assumed, sometimes rightly, that they could treat people how they liked as they have enough applicants for it to not matter. Interviews are always two-way. If you are exploiting the power dynamic in the interview process: it’s a pretty good sign you’ll be a shitty person to work for or with.

So, given all this, how did we decide to do it at Workbrew?

🎭 Stages

We split the interview process into a few stages. If you passed one: you moved onto the next one as soon as possible (usually within a few days). If you failed one: I let you know as soon as possible (ideally the same day).

For each stage when we’re evaluating the candidate, we have a numeric rubric for each question or criteria. This helps avoid biases where you “love” a candidate but, objectively, they scored lower than another.

Here’s the breakdown of our hiring stages:

-

✍️ Writing the job posting. I spent a pretty decent amount of time and got a bunch of feedback to ensure it conveys our values at Workbrew. We slimmed “requirements” down to the bare minimum (i.e. no-one would get a job who didn’t 100% meet every one). We kept the “nice-to-haves” minimal but indicative of what would differentiate a good from great candidate. Rather than implicit (“unlimited holiday/vacation”) we tried to be explicit (“less than 20 days is too few, more than 40 is too many”). We decided to share it in various semi-public locations (e.g. various networks we’re part of) rather than get a million applications from the entire public internet. We also directly reached out to some people who seemed like they’d be a good fit and were already in our network

-

💌 Application. We asked people to send in their CV/resume so we could do an initial screen to ensure they met requirements. For example, if we said we wanted 10 years industry experience and you were still in high school then: sorry, it’s a pass. I did all this myself because we’re a small company and I wanted to ensure I got it right first before I eventually delegate/outsource it. We also asked people to clarify that the salary range in the job posting worked for them. This helped ensure alignment between experience, expectations and our budget. At this stage as a company, we’re careful about balancing expectations with experience. This also provides a screening process for people who link out to their social media on e.g. their CV and it’s full of them being unkind to others. If your linked social media openly showcases behaviour clearly misaligned with our values: it’ll be a pass.

-

📺 Technical Screening Questions. Next, we asked people to reply to the email with answers to a few technical screening questions. Could people just feed these into ChatGPT and get some half-decent answers out? Yup. While ChatGPT might produce passable answers, genuinely excellent, nuanced answers stand out immediately. If you’re skilled enough to leverage AI to produce that kind of clarity: good for you (more to follow on that in another post).

-

🍐 Live Pairing Interview. Riffing off my favourite experience at AllTrails, we did a live pairing interview. Because we’re remote-first: it was done over Zoom. I get it: no-one loves live technical interviews/pairing so we factor in nervousness. To avoid unfairness, I screen-shared my environment and let them connect remotely with Zoom and/or VS Code. This enabled us to work together on the same real problem in our actual codebase. Everyone worked on the same problem and had the same amount of time for a fair comparison. This was “open book”; it was fine to use Google, ChatGPT, Copilot, Cursor, etc. I’m fine with AI tool usage as long as it’s disclosed. Some folks asked to skip this stage in favour of a take-home interview. We’re not willing to do that; there’s just too much cheating that happens with this now and it’s more fair to compare all candidates in the same environment.

-

🧫 Cultural Cofounders Interview. We’re a small and new company but we identified strong, shared cultural values early on. If someone strongly prefers to never travel to meet coworkers in person, that’s not a good cultural fit with us. To ensure all three founders were aligned: we all interview every candidate. This ensures that we’re actively excited about each new person who joins and sets everyone up for success. It also allows the candidate to ask different (or the same) questions to different founders and get different perspectives.

-

💸 Offer. We move to making offers ASAP. There might be further discussion and salary/equity/etc. We make clear that the higher the compensation: the higher the expectations. Ultimately, what value you bring is evaluated against how much you cost the company. If maximising salary is your primary goal, you’re very early career and/or in a particularly expensive city: it’s a mutually poor fit for our current state.

-

🛬 Onboarding. Despite working remotely for 16 years, I still find face-to-face working tremendously valuable. As a result, in the first week, we fly the new employee over to co-work with me in Edinburgh, Scotland. This helps with engineering and product onboarding and setting 7/30/90 day expectations. Most importantly, though, it helps us both get to know each other a bit better. It means when we read some text in Slack, we hear the human side. If we’re hiring more than one person around the same time: we build a “cohort” and onboard them together. This means they can get to know each other, too.

⏭️ Exceptions

The above sounds great (and has been) but: sometimes there are exceptions. We’ve hired people without going through every step of the process because I’ve worked with them on Homebrew for years and have extensively reviewed much of their code. For this situation, putting them through a live coding exercise is pointless.

🪩 Reflections

Reflecting on the process so far, I’m really happy with the outcomes. We’ve hired universally excellent candidates so far which makes me delighted with our process. In fact, we’ve had more excellent candidates than we’ve had headcount/budget to hire them.

Doing this process (almost) entirely by myself is tiring but worthwhile. I’ve never had such a high level of confidence in people before we’ve hired them.

We’ve seen particularly good results from hiring from shared employer backgrounds. 2 of our engineers were hired from Homebrew. 2 of our engineers (and our EM/PM hybrid and all 3 founders) had previously worked at GitHub. 1 was a (paid) referral from a respected Scottish founder.

Surprisingly, we’re yet to hire a “cold inbound” engineering hire. Several of these folks reached the pairing and cultural interviews and did well but everyone we ended up hiring did incredibly. This has indicated to me that, at least when we’re small, leaning on our networks is incredibly valuable and time-efficient. It also helps a lot with “cultural onboarding” to have shared context.

]]>Leaving GitHub

GitHub was a good ride. I got my dream of working for a “Big Tech” US tech company through an acquisition while working entirely remotely from Scotland. When we were acquired by Microsoft in 2018 I predicted to my wife that at some point the bureaucracy would be so stifling that I’d quit. To Microsoft’s credit, this took 4.5 years, much longer than I would have predicted.

When I joined GitHub as employee #232, it was already the second-largest company I’d ever worked for. No longer having Neha Batra, the best manager I’ve ever had in my career, as my manager was the straw that broke the camel’s back. When I’d mentioned this was part of my reasoning for leaving, I was told it could be fixed instantly but: that’s not really how I roll. I’d also previously told myself if I get to 10 years with any employer: I should quit to avoid stagnation, even if I loved it.

I still enjoyed it but: I no longer loved it. It just took too long to get anything meaningful done any more and I’m primarily motivated by making developers more productive, not meeting OKRs while achieving the opposite. The money was good but, at least for me, feeling like you’re actually having individual impact has to take priority.

Raise.dev

The startup I joined as a CTO and cofounder on March 1st 2023 was named “Raise.dev”. It had been started in 2019 by John Britton, my friend and former manager at GitHub. In 2021 Vanessa Gennarelli, another friend and former teammate joined him there. I almost joined him in February 2020 but my youngest child’s refusal to sleep and the prospect of a staff engineer promotion changed my mind.

John, the classy guy that he is, didn’t do a “hard sell” for me to join him at Raise.dev. If anything, it was the opposite. He introduced me to various other founders and actively encouraged me to interview elsewhere and think about it. He also said he was looking for a cofounder rather than an employee; something that was initially intimidating for me.

A person who helped swing it for me was Brian Corcoran, friend and lynchpin of the Scottish tech scene. I described my various options I was weighing up and he said “oh, so you’re cofounding the startup then?”. When I said I hadn’t decided, he told me that it was obviously the option I was most excited about.

ESP32s

When I joined John and Vanessa, they had done a bunch of market research and figured out that there was an opening for developer tools in the IoT space. In true startup style, for my first week John flew over to Edinburgh and stayed in my guest room while we figured out what we were going to build. We zoomed in on shipping something for ESP32s that would enable a GitHub-like deployment flow.

~12 weeks later, we had it in the hands of some potential users. Things did not go well: the onboarding proved punishing and not always successful. The rough edges were things that we did not have control over (e.g. GitHub Actions, C++).

When we next met up as a three to discuss what features to build next: I proposed we pivot. I didn’t know what to, just that what we were doing didn’t seem to match our strengths.

John had been trying to convince me for literally about 10 years at this point to make “a Homebrew startup”. If you haven’t heard of it, Homebrew is an open-source package manager I’ve been working on since 2009. He (and others) had intro’d me to VCs several times and I’d always gone “where’s the business here, though?” and declined to take it any further. It also felt, in that era of open-source, that most “open-source startups” were a bait-and-switch where a free, liberally licensed project was inevitably yanked away from the community for “commercial reasons” later. I wanted no part in helping someone make a quick buck out of the Homebrew community I’d worked so hard to cultivate.

John said: “well, if we’re going to play to our strengths: that’s the Homebrew startup”. I left the meeting, had dinner with my kids and thought: shit. He’s right. We couldn’t play more to our strengths than this. Homebrew now has solid finances and governance, meaning it’s resilient against negative disruption from any organisation. John, Vanessa and I all have most of our background in developer tools and open source. It just made sense.

Of course, minutes into the next meeting discussing it, John comes up with the perfect name: “Workbrew”.

Workbrew

A major advantage of being open-source was having more than a decade’s worth of public requests from large companies that Homebrew decided not to build. Many of these people were told “no” by me. Apparently I’m good at that.

With a bit of digging, the main things that jumped out were:

- Homebrew’s inability to play nicely with MDM tools

- A need to restrict access to Homebrew packages that violate compliance or regulatory requirements

- Security concerns around Homebrew’s filesystem permissions model

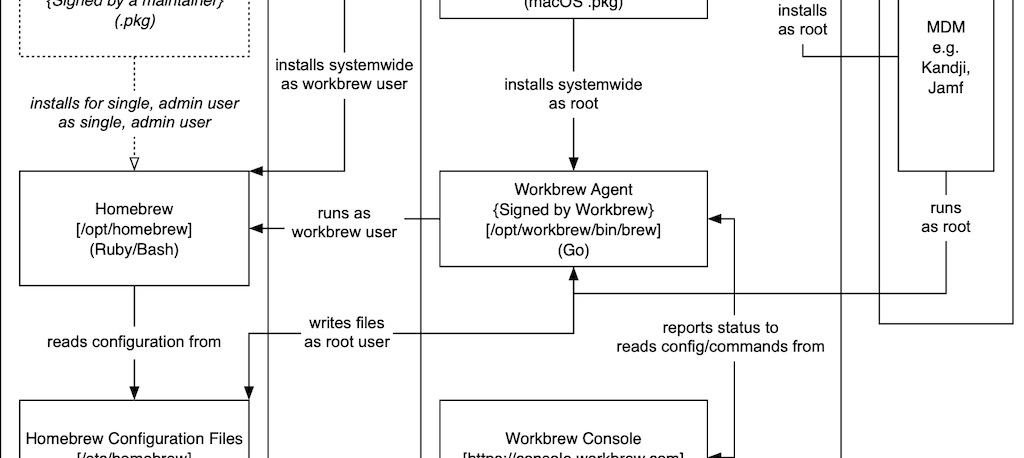

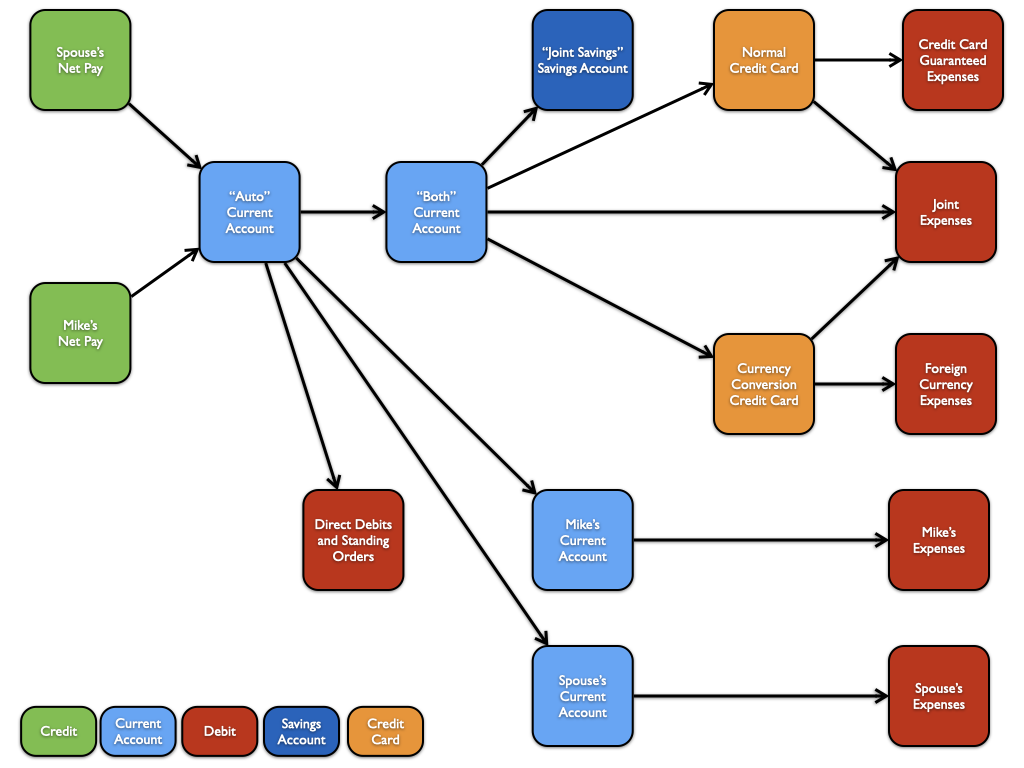

I realised fairly quickly this would necessitate the:

- Workbrew Installer: install Homebrew and Workbrew, play nicely with MDMs (written in macOS

.pkgand Bash) - Workbrew Agent: send state/receive commands to Console, provide security-enhanced wrapper for Homebrew (written in Go)

- Workbrew Console: used by administrators to send commands/receive state from devices (written in Ruby on (Guard)Rails)

I built the basic architecture solo, dogfooded it with myself, John and Vanessa and showed it to some people. This would make the open-source Homebrew project better and allow us to build an independent commercial product, Workbrew, to handle enterprise needs that Homebrew wouldn’t or couldn’t. We got a better response than I anticipated. I guess it was time to go raise some funding.

VCs

Raise.dev already had some money in the bank from an existing round that was sustaining the three of us. With Workbrew gaining momentum, we knew it was time to raise more funding to grow the team.

The TL;DR is we spoke to many VCs, I learned to be less Scottish in terms of both self-deprecation and swearing and raised a round. In true remote-first fashion, we got our first offer before the three of us had even been in the same room together as cofounders. HeavyBit were our lead investor and have proved to be a great partner and source of wisdom for us. They were (pleasantly) starting to badger me to go and hire a team so: it was time.

Hiring

I left GitHub as a “Principal Engineer”: lots of technical mentoring, but no formal management or hiring responsibilities.

I’ve written a longer post on exactly what my interview process was but, suffice to say, it worked out pretty well. We’ve got an incredible, world-class remote-first team with strong cultural alignment. Today, ~63% of us are ex-GitHub employees. Only the cofounders came directly from there. Our shipping velocity is absurdly fast (with guardrails). We help each other, we improve each other and we prioritise kindness and empathy. We work mainly async together across 7 countries and 3 continents. I love it.

Customer Feedback

So far, we have managed to get a decent number of happy, paying customers. Customer feedback is a beautiful and valuable thing. We’re following our tweaked versions of a few great existing processes:

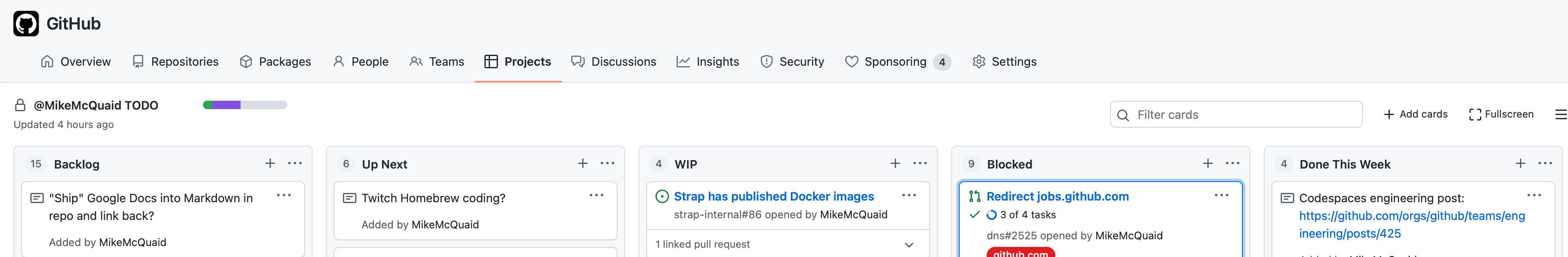

- Shape Up for 6 week “sprints” on feature work, 2 week “cooldowns” for less structured work

- the “First Responder” pattern for managing engineering support escalations and other unplanned work

- shipping “minimum loveable products” of our features with the goal of getting something useful out to customers ASAP and iterate based on their feedback

In the words of Level:

We’re happy to have integrated Workbrew into our stack. We also wanted to mention that the Workbrew team has been very responsive to even the silliest of questions and it’s been a real delight conversing with them.

The Future

Things are going well and everything is trending in the right direction. We’re working with our sales and GTM folks to delight existing and new customers.

Reflections

I’d read a lot about cofounding a company before doing it. I swore I’d never do it. Whoops. The only thing I knew for sure was that I didn’t want to do this alone (and I’m glad I didn’t). John and Vanessa and I all love, help, praise, improve and irritate each other in equal measure. It’s an incredibly intense relationship and experience. Vaguely similarly to being a parent: the highs are higher and the lows are lower than I expected. I’ve never felt like I’ve been growing more and faster than I am now, though. It’s incredibly motivating to be learning so much and building a company of people who love being here.

Advice

I feel like I have almost zero actual advice to give other founders but I feel obligated to try some:

- Starting a company requires ignoring just the right amount of conventional wisdom. Not all of it, definitely not none of it.

- You’ll get lots of (unsolicited) advice from lots of people. Listen to all of it. A broken clock is right twice a day. Ignore most of it, particularly strong opinions from those who’ve never been near a startup.

- Play to your strengths. It might be that you, as a CTO, are ok at management but still very productive with coding. Stopping all coding and fixating on management, even if wiser minds nudge you in that direction, seems like a mistake with that in mind. “Minimum viable management” is helpful. Zero management is not.

Thanks for reading!

]]>- Homebrew (2009-present): created 2009, I started working on it ~5 months in and was maintainer #3.

- AllTrails (2012-2013): created 2010, I was employee ~#8 and worked on their (smallish) Ruby on Rails application for ~1.5 years.

- GitHub (2013-2023): created 2007, I was employee ~#232 and worked on their (huge) Ruby on Rails application for ~10 years.

- Workbrew (2023-present): I cofounded Workbrew in 2023 and built the Workbrew Console Ruby on Rails application from scratch.

Over all of these Ruby codebases, there’s been a consistent theme:

- Ruby is great for moving fast

- Ruby is great for breaking things

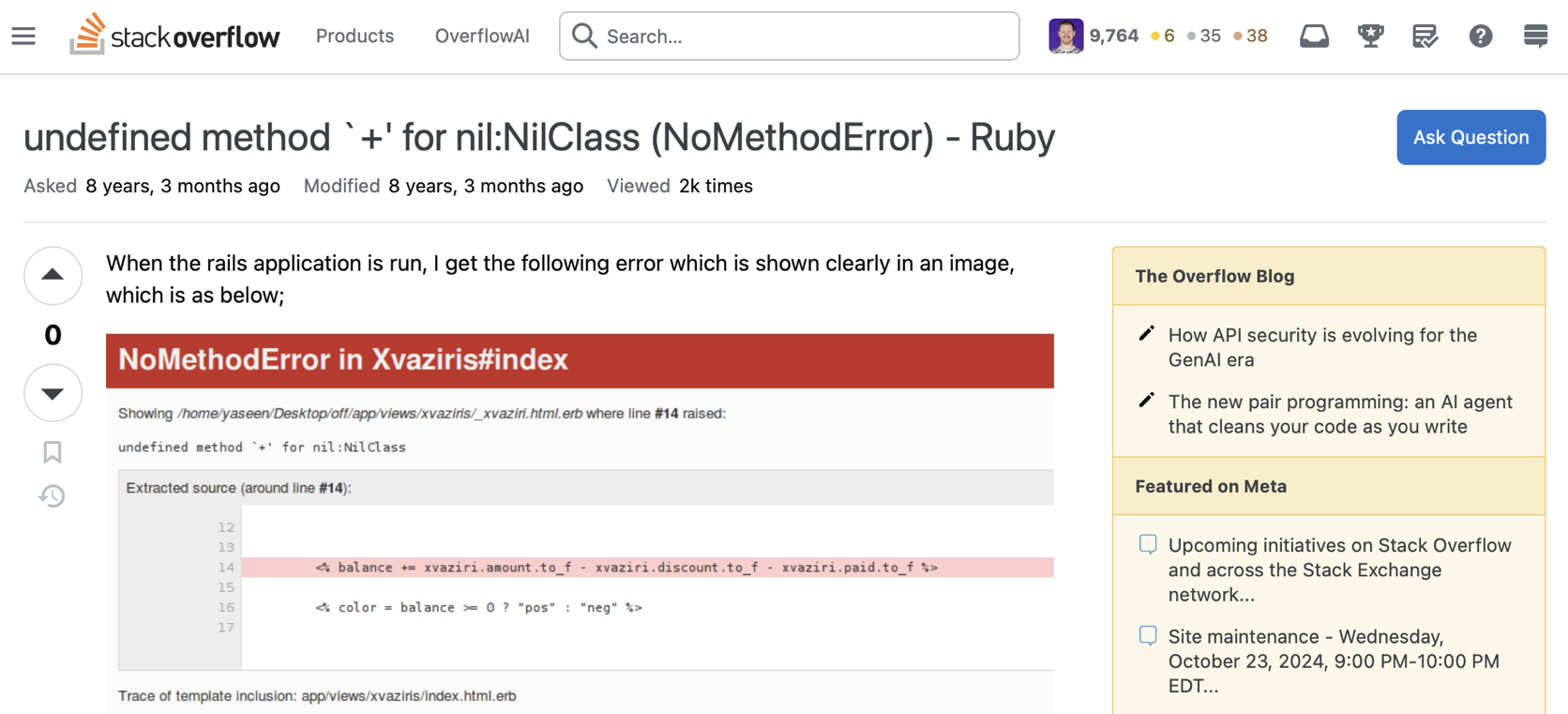

What do I mean by “breaking things”?

If you’ve been a Ruby developer for any non-trivial amount of time, you’ve lost a non-trivial amount of your soul through the number of times you’ve seen this error. If you’ve worked with a reasonably strict compiled language (e.g. Go, Rust, C++, etc.) this sort of issue would be caught by the compiler and never make it into production. The Ruby interpreter, however, makes it very hard to actually catch these errors at runtime (so they often do make it into production).

This is when, of course, you’ll jump in with “well, of course you just need to…” but: chill, we’ll get to that. I’m setting the scene for:

🤨 The Solution

The solution to these problems is simple, just …

Actually, no, the solution is never simple and, like almost anything in engineering: it depends entirely on what you’re optimising for.

What I’m optimising for (in descending priority):

- 👩💻 developer happiness: well, this is why we’re using Ruby. Ruby is optimised for developer happiness and productivity. There’s a reason many Ruby developers love it and have stuck with it even when it is no longer “cool”. Also, we need to keep developers happy because otherwise they’ll all quit and I’ll have to do it all myself. That said, there’s more we can do here (and I’ll get to that).

- 🕺 customer/user happiness: they don’t care about Ruby or developers being happy. They care about having software that works. This means software where bugs are caught by the developers (or their tools) and not by customers/users. This means bugs that are found by customers/users are fixed quickly.

- 🚄 velocity/quality balance: this is hard. It requires accepting that, to ship fast, there will be bugs. Attempting to ship with zero bugs means shipping incredibly slowly (or not at all). Prioritising only velocity means sloppy hacks, lots of customer/user bugs and quickly ramping up tech debt.

- 🤖 robot pedantry, human empathy: check out the post on this topic. TL;DR: you want to try to automate everything that doesn’t benefit from the human touch.

The Specifics

Ok, enough about principles, what about specifics?

👮♀️ linters

I define “linters” as anything that’s going to help catch issues in either local development or automated test environments. They are good at screaming at you so humans don’t have to.

- 👮♀️

rubocop: the best Ruby linter. I generally try to enable as much as possible in Rubocop and disable rules locally when necessary. - 🪴

erb_lint: like Rubocop, but for ERB. Helps keep your view templates a bit more consistent. - 💐

better_html: helps keep your HTML a bit more consistent through development-time checks. - 🖖

prosopite: avoids N+1 queries in development and test environments. - 🪪

licensed: ensures that all of your dependencies are licensed correctly. - 🤖

actionlint: ensures that your GitHub Actions workflows are correct. - 📇

eslint: when you inevitably have to write some JavaScript: lint that too.

I add these linters to my Gemfile with something like this:

group :development do

gem "better_html"

gem "erb_lint"

gem "licensed"

gem "rubocop-capybara"

gem "rubocop-performance"

gem "rubocop-rails"

gem "rubocop-rspec"

gem "rubocop-rspec_rails"

end

If you want to enable/disable more Rubocop rules, remember to do something like this:

require:

- rubocop-performance

- rubocop-rails

- rubocop-rspec

- rubocop-rspec_rails

- rubocop-capybara

AllCops:

TargetRubyVersion: 3.3

ActiveSupportExtensionsEnabled: true

NewCops: enable

EnabledByDefault: true

Layout:

Exclude:

- "db/migrate/*.rb"

Note, this will almost certainly enable things you don’t want.

That’s fine, disable them manually.

Here you can see we’ve disabled all Layout cops on database migrations (as they are generated by Rails).

My approach for using linters in Homebrew/Workbrew/the parts of GitHub where I had enough influence was:

- enable all linters/rules

- adjust the linter/rule configuration to better match the existing code style

- disable rules that you fundamentally disagree with

- use safe autocorrects to get everything consistent with minimal/zero review

- use unsafe autocorrects and manual corrections to fix up the rest with careful review and testing

When disabling linters, consider doing so on a per-line basis when possible:

# Bulk create BrewCommandRuns for each Device.

# Since there are no callbacks or validations on

# BrewCommandRun, we can safely use insert_all!

#

# rubocop:disable Rails/SkipsModelValidations

BrewCommandRun.insert_all!(new_brew_command_runs)

# rubocop:enable Rails/SkipsModelValidations

I also always recommend a comment explaining why you’re disabling the linter in this particular case.

🧪 tests

I define “tests” as anything that requires the developer to actually write additional, non-production code to catch problems. In my opinion, you want as few of these as you can to maximally exercise your codebase.

- 🧪

rspec: the Ruby testing framework used by most Ruby projects I’ve worked on. Minitest is fine, too. - 🙈

simplecov: the standard Ruby code coverage tool. Integrates with other tools (like CodeCov) and allows you to enforce code coverage. - 🎭

playwright: dramatically better than Selenium for Rails system tests with JavaScript. If you haven’t already read Justin Searls’ post explaining why you should use Playwright: go do so now. - 📼

vcr: record and replay HTTP requests. Nicer than mocking because they test actual requests. Nicer than calling out to external services because they are less flaky and work offline. - 🪂

parallel_tests: run your tests in parallel. You’ll almost certainly get a huge speed-up on your multi-core local development machine. - 📐 CodeCov: integrates with SimpleCov and allows you to enforce and view code coverage. Particularly nice to have it e.g. comment inline on PRs with code that wasn’t covered.

- 🤖 GitHub Actions: run your tests and any other automation for (mostly) free on GitHub.

I love it because I always try to test and automate as much as possible.

Check out Homebrew’s

sponsors-maintainers-man-completions.ymlfor an example of a complex GitHub Actions workflow that opens pull requests to updates files. Here’s a recent automated pull request updating GitHub Sponsors in Homebrew’sREADME.md.

I add these tests to my Gemfile with something like this:

group :test do

gem "capybara-playwright-driver"

gem "parallel_tests"

gem "rspec-github"

gem "rspec-rails"

gem "rspec-sorbet"

gem "simplecov"

gem "simplecov-cobertura"

gem "vcr"

end

In Workbrew, running our tests looks like this:

$ bin/parallel_rspec

Using recorded test runtime

10 processes for 80 specs, ~ 8 specs per process

....................................................................

....................................................................

....................................................................

....................................................................

....................................................................

....................................................................

....................................................................

......................

Coverage report generated to /Users/mike/Workbrew/console/coverage.

Line Coverage: 100.0% (6371 / 6371)

Branch Coverage: 89.6% (1240 / 1384)

Took 15 seconds

I’m sure it’ll get slower over time but: it’s nice and fast just now and it’s at 100% line coverage.

There has been (and will continue to be) many arguments over line coverage and what you should aim for. I don’t really care enough to get involved in this argument but I will state that working on a codebase with (required) 100% line coverage is magical. It forces you to write tests that actually cover the code. It forces you to remove dead code (either that’s no longer used or cannot actually be reached by a user). It encourages you to lean into a type system (more on that, later).

🖥️ monitoring

I define “monitoring” as anything that’s going to help catch issues in production environments.

- 💂♀️ Sentry (or your error/performance monitoring tool of choice): catches errors and performance issues in production.

- 🪡 Logtail (or your logging tool of choice): logs everything to an easily queryable location for analysis and debugging.

- 🥞 Better Stack (or your alerting/monitoring/on-call tool of choice): alerts you, waking you up if needed, when things are broken.

I’m less passionate about these specific tools than others. They are all paid products with free tiers. It doesn’t really matter which ones you use, as long as you’re using something.

I add this monitoring to my Gemfile with something like this:

group :production do

gem "sentry-rails"

gem "logtail-rails"

end

🍧 types

Well, in Ruby, this means “pick a type system”. My type system of choice is Sorbet. I’ve used this at GitHub, Homebrew and Workbrew and it works great for all cases. Note that it was incrementally adopted on both Homebrew and GitHub.

I add Sorbet to my Gemfile with something like this:

gem "sorbet-runtime"

group :development do

gem "rubocop-sorbet"

gem "sorbet"

gem "tapioca"

end

group :test do

gem "rspec-sorbet"

end

A Rails view component using Sorbet in strict mode might look like this:

class AvatarComponent < ViewComponent::Base

sig { params(user: User).void }

def initialize(user:)

super

@user = user

end

sig { returns(User) }

attr_reader :user

sig { returns(String) }

def src

if user.github_id.present?

"https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/u/#{user.github_id}"

else

...

end

end

In this case, we don’t need to check the types or nil of user because we know from Sorbet it will always be a non-nil User.

This means, at both runtime and whenever we run bin/srb tc (done in the VSCode extension and in GitHub Actions), we’ll catch any type issues.

These are fatal in development/test environments.

In the production environment, they are non-fatal but reported to Sentry.

Note: Sorbet will take a bit of getting used to.

To get the full benefits, you’ll need to change the way that you write Ruby and “lean into the type system”.

This means preferring e.g. raising exceptions over raising nil (or similar) and using T.nilable types.

It may also include not using certain Ruby/Rails methods/features or adjusting your typical code style.

You may hate it for this at first (I and many others did) but: stick with it.

It’s worth it for the sheer number of errors that you’ll never encounter in production again.

It’ll also make it easier for you to write fewer tests.

TL;DR: if you use Sorbet in this way: you will essentially never see another nil:NilClass (NoMethodError) error in production again.

That said, if you’re on a single-developer, non-critical project, have been writing for a really long time and would rather die than change how you do so: don’t use Sorbet.

😌 Ad Hominem

Well, I hear you cry, “that’s very easy for you to say, you’re working on a greenfield project with no legacy code”. Yes, that’s true, it does make things easier.

That said, I also worked on large, legacy codebases like GitHub and Homebrew that, when I started, were doing very few of these things and now are doing many of them. I can’t take credit for most of that but I can promise you that adopting these things was easier than you would expect. Most of these tools are built with incrementalism in mind.

Perfect is the enemy of good. Better linting/testing/monitoring and/or types in a single file is better than none.

🤥 Cheating

You may feel like the above sounds overwhelming and oppressive. It’s not. Cheating is fine. Set yourself strict guardrails and then cheat all you want to comply with them. You’ll still end up with dramatically better code and it’ll make you, your team and your customers/users happier. The key to success is knowing when to break your own rules. Just don’t tell the robots that.

]]>Perhaps surprisingly: I don’t actually give the tiniest shit whether he was ignorant, malicious or a “good person” and: you shouldn’t either.

Imagine you have two radically different coworkers: Bob and Alice.

- Bob’s daily ritual includes a heartfelt plea to himself: “Today I’m going to try so hard and, for once, make sure everything goes well and that I don’t upset anyone!”. Alas, Bob, as usual, fucks it all up. He starts the day strong, bringing the team doughnuts. It’s all downhill from there, though: he breaks the CI build, offends several teammates, baptises his boss with hot coffee and orchestrates a massive colossal system outage affecting all paying customers. He apologises profusely but everyone knows: he’ll do it all again tomorrow.

- Alice starts her day with a sigh: “Work is hard right now and I can’t really be bothered but: gotta pay the bills somehow.”. Alice, as usual, has a sensational day. She completes her project weeks ahead of the deadlines, spends an hour helping the new hire open their first PR, saves the day on Bob’s site outage and fixes his broken CI build. At lunchtime, though, she’s tired so listens to a podcast sitting by herself. She’s invited to a party with a few coworkers at the weekend: she politely passes, her friends are outside of work. She’ll go to the next one but it irks people that she doesn’t seem to care enough about being liked. From this description: Bob is a lovely, if very unlucky, person and Alice is a high-performing antisocial person.