by Richard Osman

This clever confection is a mystery about murderers who don’t kill people and murders that mysterious do not occur. It’s spun sugar, but in the days after the murder of Alex Pretti, perhaps confectionery is what we require.

| CARVIEW |

The purpose of art is to delight us; certain men and women (no smarter than you or I) whose art can delight us have been given dispensation from going out and fetching water and carrying wood. It's no more elaborate than that. — David Mamet

This clever confection is a mystery about murderers who don’t kill people and murders that mysterious do not occur. It’s spun sugar, but in the days after the murder of Alex Pretti, perhaps confectionery is what we require.

Winner of a Hugo for Best Novella, this is the story of a tea monk — a sort of itinerant psychotherapist — who meets a robot on the road. Robots were emancipated long ago, and long ago they left and absented themselves in the wilderness. Now, a volunteer has been sent to check up on how the humans are doing. The result is very heavy on exposition, and indeed nearly everything here is exposition. The robot, whose name is Splendid Speckled Mosscap, owes something to Iain M. Banks but is exceptionally well drawn.

This is perfect. I’ve been reading a lot of Twitter from Fania Oz-Salzberger about October 7 and the ensuing war; she, along with Simon Schama and Simon Sebag-Montefiori, has made consistent good sense.

This volume a wonderful essay on strong women in (and out of) the Bible, some terrific notes on humor, and demonstrates a wonderful (and I think sound) approach to the problem that the ultra-orthodox pose to secular Jews.

Also, this was a delightful read.

Speaking of tech support: when you need help or advice on a project, it often helps to describe just what you’re doing. Yes, some aspects may be confidential, but a general outline saves lots of time and potential confusion. Having trouble with footnotes? You might have seven, or you might have thousands, and it makes a difference. Michael Bywater once said, “A man has no secrets from his valet, or his software developer.”

This week’s Tinderbox meetup was a deep dive into the meaning of names in Tinderbox. Each Tinderbox note has a name and a text space; the name is typically a short descriptive title and the text can as long as you like. What are the names for?

In the beginning, in Tinderbox’s Storyspace prehistory, the name was a way to identify which note was which on a small, low-resolution screen. In Storyspace 1, the title was a Str32 — a 32-character buffer — because there wasn’t a proper string library for Pascal in the 80s. (It wasn’t my fault, though most of the design errors since those days are.). I’m not sure it was done with much thought; I didn’t think much about it for a long time, beyond wanting to get rid of those fixed buffers.

The duality between title and text, though, has always been interesting. In afternoon, the titles are often in tension with the text. The note named “poetry” begins with a question: “

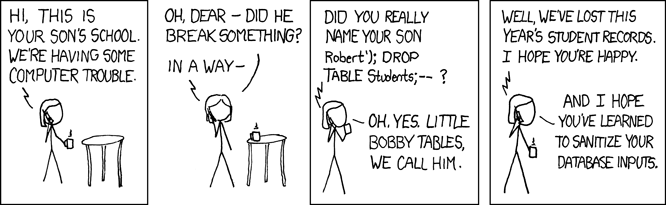

But Names in Tinderbox let actions refer to other notes and use them as prototypes or as sources of data. If you want to do this, the naming of notes can be a difficult matter. For once thing, it becomes desirable for notes to have distinct names. For another, names that look like actions can cause trouble, just like little Bobby Tables.

In the forum, this prompted Andreas Grimm to raise the concept of Wittgenstein’s Ladder. Tinderbox tech support sometimes requires the philosophy of language.

(Speaking of early Tinderbox, I recently scrapped support for #operators, which were used in queries in Tinderbox 1-2 and have been deprecated for 20 years. “Surely,” I told myself, “no one is still using them!” Dear reader, this weblog was still using them, and the change broke my booklist for a time.)

If we are to free ourselves from subservience to ignorance and cruelty, it will not be through the new civil war that the Silicon Sovereigns sometimes imagine, the hordes of brown-hued rioters spreading out from ruined cities to loot their Fatherland. We will not have a second Gettysburg; armies don't work like that anymore.

What it will be—what it will have to be—is a notionally amicable separation in which a notional Union is preserved for old time’s sake, while we keep ourselves separate and avoid meeting, talking, or having anything to do with the others.

That’s already well advanced. When I was a kid, I knew Republicans. Today, I believe I know one actual Republican, a guy who runs my fantasy baseball league. I am acquainted with two or three more, kids I knew at school, a college classmate who got a little but famous, a second cousin once removed who has a Facebook habit. There was a Republican in hypertext research, back in the 90s, but I haven’t heard from him in decades.

But that’s not enough, not when the Red States are sending ICE to shoot people in the face for fun. We need a restraining order.

The murder of Renee Nichole Good by ICE officer Jonathan Ross, who remains at large, has upset me deeply. It has been hard to work. Objectively, I’ve shipped a Tinderbox backstage release with some fairly ambitious new fixes, straightened out a tricky support issue on Tinderbox actions, made some progress on AI fiction and paid the mid-month bills. Still, it feels like I can do nothing but Twitter, Facebook, and Chess.com.

Half the country thinks this is just fine. The President, the Vice President, Kristi Noem, Robbie George: she had it coming. The local Dems: a collective shrug, not even a meeting.

I think that, if you believe this is OK, I do not want to break bread with you, I do not want to meet with you, I do not want to know you, and I do not want to be governed by you—not even if you have the votes.

This happened before, in 1775-1776 and again 1859-1860. I think disunion may be the only resolution.

I read David Owen’s recent New Yorker piece on dyslexia with special interest, because I am dyslexic. The New Yorker piece is pretty good, though it’s also dismaying that the Gillingham approach, an experimental reading program that saved my bacon back in the early 60s, is still experimental. It does appear that we know a bit more about the neuroanatomical basis for dyslexia thanks to MRI studies, and there may even be some evolutionary reasons that is makes sense for social hunting animals to keep around neurodivergent strains; we might not be great at reading but, it seems, there are compensations that stem from a differing approach to exploration.

A fascinating research report from a fascinating researcher. Wolfram studies cellular automata, which are very small and simple models of abstract computation in which each “cell” adjusts its state according to the state of some number of neighbors. These automata are even simpler than neural networks, but they, too, can learn. It appears that machine learning, in this case at least and perhaps in all cases, including animals and people, may be a matter of sampling lots of abstract computations and refining those that seem to have some slight utility for addressing the current situation.

Andy Brice asks, “Is the golden age of Indie software over?” He thinks it may well be ending, crushed between Google-driven enshitification, AI slop, and fraud. The decay of the open web poses a terrible threat to small internet businesses of all kinds. Certainly, most of the artisanal software crowd are experiencing hard times.

It’s worth noting, by the way, that two of our regulars have been living through war the last two years. Bomb shelters haven’t been part of our everyday plans for a long time. I suspect, though, that war is going to be a more frequent visitor in the coming years.

I think Andy Brice is too pessimistic, and that the best is yet to come, assuming the end of the world doesn’t arrive first.

First, the core problem is that we have only three sources of personal computers: Apple, Google, and Microsoft. Those three companies have worked to destroy artisanal software for more than a generation in order to secure more complete monopolies over the world of computing. They drive out competition and innovation by giving away software bundled with their hardware, and pretend to open up third-party opportunities while ensuring that those opportunities are only attractive to ignorant judges. But this cannot succeed long term because, in the long term, each customer wants to do their best work. If buying a better tool gets that novel finished or closes the next deal faster, you’re going to buy that tool.

This is made worse because Google is using its ad monopoly to build a software monopoly, and the road to that second monopoly requires treating independent software creators as equivalent to pornographers and online casinos. So, even if AdWords still worked, we are not permitted to buy them. It’s clearly an antitrust violation but no one has enforced those in ages aside from occasional big mergers. This won’t work in the long run, but it may be a near-run thing. I’m hoping my Senator and my Congreswoman may notice.

The pandemic still casts a shadow over software because it’s led lots of people to reassess their work, and led some people to just not care very much about their work. There’s still a lot of depression in the air. A lot of people get high on resentment; why work when you can have fun owning the libs and making jokes about trans people? This won’t last forever, but it might take a generation for the smoke to clear. (The last time it happened, the smoke cleared just in time for WW2. Just saying: keep smiling through just as you always do, and gather the rosebuds because they are not long, the days of wine and roses.)

AI will make a huge difference, but not in the way either the pundits or the Hacker News crowd seem to expect. Bob Martin has been crusading against vibe coding and he is not wrong: for code, Claude is wildly overconfident and has lousy taste. There’s apparently a plan at Microsoft to recode everything in Rust with a quota of a million lines of C++ per engineer per month. I’m sure that’s going to be peachy. And yes, some pointy-headed managers will stage big layoffs for the thrill of the thing, and hope to blame someone else for the consequences.

AI is bad at making stuff, and amazing at helping you make stuff. You don’t ask Gemini for the state of the tide, not if that matters to you, any more than you ask your eight year old kid. Sure, Bobby’s usually right, but if you don’t want to go aground, you’d better check. But AI is terrific at explaining how tides work and how we came to know, and AI is pretty good at telling you whom to ask. Even if the AI is wrong, you’ll find out right away; if it’s right, you’ll know the tides.

Much of the time, today’s AI is like a smart, unmotivated student: it knows a lot of stuff, but really has no idea what to do with that knowledge or why you would want do anything with knowledge in the first place. Remember: that’s not worthless!

The theme for this year’s festival of artisanal software is artisanal intelligence. Don’t ask the AI to do your work; use the AI to help make your work better. Let it get you unstuck when you hit a roadblock. Let it work through the tedious chores.

But remember, please, the Law by which we live,

We are not built to comprehend a lie,

We can neither love nor pity nor forgive.

In “Baker Beware”, Brenda Goodman excoriates AI-generated recipe pages. These pages look like normal recipe blogs but they’re churned out mechanically, page after page, each carefully attuned to appeal to Google’s SEO algorithm. Google, having destroyed weblogs through its zeal for ad revenue, is now swamped by nonsensical recipe pages like “chocolate acorns with nut-covered caps” that Goodman found online. The AI slop is preposterous.

Yet, this is not the fault of AI! This is the fault of deceptive grifters, colluding with Google to waste your time and also to steal money from small businesses who pay good money for worthless ads.

A significant strand of the literature on AI and cognition argues that machines cannot be intelligent as we are, because machines have no bodies. This should be most clearly evident when the AI is asked to reason about sensual pleasures like good food and great music, pleasures it simply cannot know. (I am skeptical of this approach because people who are deaf or blind are not unintelligent, but certainly bodies matter to the human condition.) So, we might expect AIs to be especially bad when talking about food.

Claude (Sonnet 4.5) is remarkably capable when it comes to food. “My focaccia is pretty good,” I told it. “I use Ruhlman’s 5:3 ratio: 5 parts flour (by weight) to 3 parts water, plus yeast, olive oil and salt. But my focaccia isn’t nearly as puffy as the bakery’s, and it never has those big bubbles. What am I doing wrong?” Claude came back right away to say that my 63% hydration ratio was too low, and that I should try 70% or even 75%. It went on to say that high-hydration doughs could be hard to handle, and suggested I ease into it with 70%. This is good cooking and good pedagogy.

Claude was also quite good about menu planning for my last dinner party. I gave it my planned menu. “That’s enough for twice as many guests. Three desserts?!” I explained the circumstances, and it partly relented: a bit of excess could be generous and comforting. Still, the first course was far too rich, it thought, and I should replace the planned dauphinoise alongside the roast beef with something more lean. I settled on roasted squash.

Claude knows about trends in food and the history of cooking. When we got talking about a modernist interpretation of Stroganoff, it suggested a stock reduction, shallots, a touch of Dijon, and crème fraîche. Claude is quite skeptical of classical French sauces, in fact, even though it is aware that I am not.

What would happen if Claude were hallucinating, just making stuff up? Nothing! If it were wildly off-base, I know enough to see what cannot possibly work. Even if I did not see it right away, it would soon become evident. And we’re all too concerned with recipes anyway; even if you don’t bother to let the bread rise once, much less twice, it may very well work out. It’s just dinner.

On Twitter, Celeste Ng has been campaigning for AI content warnings. “Would that include,” I wondered, “asking an AI to help you work through the statistical mechanics you never quite mastered in college, if you needed it for a story?” Ng’s response was sensible in context: what harm does the acknowledgment do? Another twitter account (who turned out to be a fundamentalist nut and whom I blocked) lit into me: how could I know that the statistical mechanics it was explaining was not a hallucination? The same way I know that the stuff in a textbook isn’t hallucination (and, yes, on occasion that, too, has happened to me): you work through problems, you use the theory, and you see whether it blows up or not.

One morning last month I got the flu and COVID shots, and my midday I was back on my heels. Knowing I was not in top form, I thought I’d try letting Gemini have a loose rein and let is guide a rather messy bug hunt in Tinderbox’s JSON code. I’d sit back and see what Gemini proposed.

Gemini was completely at sea, but close enough to plausibility that I kept being tempted to let it try just one more patch, one additional escape sequence, one more fix. The results were worse and worse. After a few hours of this, I used the version control system to roll back to the morning and headed for the barn.

Both Claude and Gemini are remarkable assistants, but neither is particularly strong on either strategy or elegance. If you guide them, they can refactor, but their own ideas of refactoring are seldom sound. Yet, both are remarkably strong on syntax questions; I’ve yet to encounter a syntax error they cannot explain. They’re both terrific at analyzing crash logs, though they remain too confident that their proposed solutions will suffice.

Reid set out to write a love story, and it’s adorable. I’m struck that a Lesbian love story set in a time I remember can seem sentimental and nostalgic, but here we are. Not everything about our time is awful.

Reid missed that, in searching for colorful background, she also committed herself to writing a School Story, or possibly a Boot Camp Story. Joan and Vanessa are Astronaut Candidates in the early 1980s. It doesn’t really seem like the 1980s: the book unfolds a dozen years after Stonewall, but it never seems to have occurred to Asst. Prof. Joan Goodwin that she might be gay. Allison Bechdel figured in out when she went to college (in 1979); Joan is about a decade older and has a PhD, but then again she’s a Texan. The obligatory training scenes are sometimes good and sometimes feel tacked together.

This is also a Flight Story, and this is a missed opportunity. Reid isn’t that interested in astronomy (Joan’s field) or flying (Vanessa’s passion), and has a better idea of how she might pitch astronomy to her readers than piloting. That’s a shame because, from a very early stage in the first chapter, the reader knows precisely where this is heading: Vanessa Ford is going to get her dream of piloting a space shuttle and be taught to be careful what you wish for.

Despite all this, I quite liked this book.

It is 1989, and the sleepy Austrian border town of Darkenbloom proceeds on its way, not yet knowing that history has not, in fact, ended. A stranger comes to town, looking for mass graves. A group of students come to restore the abandoned Jewish cemetery. The town physician, who has been there since his 1930s assignment to replace Dr. Bernstein, wants to retire. Dr. Alois, who used to be assistant Gauleiter, wants to do small favors and offer advice. And Farmer Faludi wants to build a big water tank is the disused Rotenstein meadow.

This reflection on AI and its shortcomings, published in 2024, is an able argument that machines are not and will not become intelligent, that they merely fool us by writing the sorts of things a person might write. That was what I thought in 2024, too, pretty much. I do not think that position is supportable today, save by adopting a vitalist position that amounts to insisting on ensoulment. Yes, it is hard to think of intelligence that is not embodied, but we have a name for people who think about things that are not easy to think about, and that name is “philosopher.”

Claude Sonnet 4.5, for example, is quite good at thinking about food and cooking. I asked it for some ideas for using leftover roast beef; it suggested hash, or a composed salad, or a stroganoff. From previous discussions I know that Claude is not a fan of classical roux-thickened sauces, so I asked if it had ideas for a modern stroganoff. “Yes!” it replied, suggesting crème fraîche in place of sour cream, fresh pappardelle in place of egg noodles, reduced beef stock for body, and asian mushrooms in place of the usual white mushrooms. Claude was anxious that the beef be sliced thinly and only barely heated. Claude, of course, has never had dinner, but it sure knows how to talk about food. (On classical music, however, Claude seems to be completely as sea.)

Vallor holds that a machine cannot be intelligent because it is not like us: it has no body, it has no senses, it has no past. All it knows is how to make plausible noises. But that may be all we know, too; it's a disturbing thought, but there it is.

A fine short biography of the philosopher who explored, among much else, the questions of whether language is complete: are there things that can be known but cannot be expressed in language? Wittgenstein had a knack for knowing people: at school, there was a boy a couple of classes ahead of him named Hitler. His brother Paul was a concert pianist, and when he lost an arm in the First World War he went right ahead an commissioned a repertoire of piano work for the left hand, a collection that would prove invaluable to Leon Fleisher when Fleisher lost the use of his right hand. Wittgenstein was also strange and perverse fellow who quarreled with his admirers, disparaged his teachers, and deplored his own character. Essentially friendless, when Vienna grew unwelcoming to Jews he slotted directly into a lectureship at Cambridge. He frequently lived in people’s spare rooms. Wittgenstein was impatient with amateur philosophy, but seldom read philosophy himself and cost himself a good deal of trouble because, wanting a degree, he refused to cite sources in his dissertation.

mnA scullery maid in 16th century Spain has secrets. First, she knows some songs which she can sing to do things like salvage burnt bread or unlock a chest without the key. Second, her grandparents were Jews. She has good reason to keep her head down, but her social-climbing mistress wants to use Luzia’s abilities to improve her status. Things get out of hand, as we know they will, and her handsome tutor is not exactly as he seems.

James Somers, Open Mind (in The New Yorker): the most sensible appreciation of AI in some time.

I’ve spent much of this week revising the Tinderbox Hyperbolic View, which shows a map of links in a non-Euclidean space. Why do you need non-Euclidean geometry? Here’s a link map of part of my novel, Those Trojan Girls.

This is focused on one of the middle chapters, and we can see that some long roads lead here, and also that the outbound path to On The Road leads to repercussions.

The existing code was five years old, and my coding style has changed a bit. I never really trusted the geometry, because my grasp of the Poincaré disk was not really satisfactory. Once before, I’d tried a big refactoring to sort things out, but it had ended in a tangle.

This time, though, I had Claude and Gemini. The point was not to vibe code or to race; the point was that Claude does understand hyperbolic geometry better than I. So, I’d show Claude some dodgy code and ask, “Is this mixing up coordinate systems?” Too often, the answer was “Yes!” I’ve complained previously the Claude is sycophantic, but Sonnet 4.5 is more direct and will stand up to you when it is right.

So, in time we built separate classes for DiskPoint and ScreenPoint, and sorted out when to use what. Lots of methods got moved to the Point classes, and the class that calculates the curved lines between notes had to be completely revamped. (In hyperbolic geometry, a circular arc is, in fact, the shortest distance between two points.)

I’m not happy with the typography and I suspect the damping is too high, but it's really behaving far better than before.

@eastgate

The design of Tinderbox, and how ideas in art, literature, and philosophical thought shape the systems we use. $34.95 (312 pages, eBook). Read more.

Exploring not only how to use Tinderbox but also why it works as it does. $34.95 (492 pages, eBook). Read more.

New media in the age of Trump. From the revolution in retail politics when nobody goes to the diner or answers their doorbell, to responsible AI research, to a yarn about an actual holodeck on an actual starship . $29.95 (130 pages, paperback). Read more.

Thoughts on my recent reading. Mouseover the covers for notes.

This clever confection is a mystery about murderers who don’t kill people and murders that mysterious do not occur. It’s spun sugar, but in the days after the murder of Alex Pretti, perhaps confectionery is what we require.

(close)For some time, I’ve needed a sounder foundation for my claim (in Uncle Fred’s Book) that Jews are inclined to argue. It’s true, as my cousin reminds me, that this goes without saying and really needs no justification. I want to have the footnote, just in case.

This is perfect. I’ve been reading a lot of Twitter from Fania Oz-Salzberger about October 7 and the ensuing war; she, along with Simon Schama and Simon Sebag-Montefiori, has made consistent good sense.

This volume a wonderful essay on strong women in (and out of) the Bible, some terrific notes on humor, and demonst...

(close)Winner of a Hugo for Best Novella, this is the story of a tea monk — a sort of itinerant psychotherapist — who meets a robot on the road. Robots were emancipated long ago, and long ago they left and absented themselves in the wilderness. Now, a volunteer has been sent to check up on how the humans are doing. The result is very heavy on exposition, and indeed nearly everything here is exposition. The robot, whose name is Splendid Speckled Mosscap, owes something to Iain M. Banks but is exceptionally well drawn.

(close)A fascinating research report from a fascinating researcher. Wolfram studies cellular automata, which are very small and simple models of abstract computation in which each “cell” adjusts its state according to the state of some number of neighbors. These automata are even simpler than neural networks, but they, too, can learn. It appears that machine learning, in this case at least and perhaps in all cases, including animals and people, may be a matter of sampling lots of abstract computations and refining those that seem to have some slight utility for addressing the current situation.

(close)This reflection on AI and its shortcomings, published in 2024, is an able argument that machines are not and will not become intelligent, that they merely fool us by writing the sorts of things a person might write. That was what I thought in 2024, too, pretty much. I do not think that position is supportable today, save by adopting a vitalist position that amounts to insisting on ensoulment. Yes, it is hard to think of intelligence that is not embodied, but we have a name for people who think about things that are not easy to think about, and...

(close)Reid set out to write a love story, and it’s rather adorable. I’m struck that a Lesbian love story set in a time I remember can seem sweetly nostalgic, but here we are. Not everything about our time is awful.

Reid missed that, in searching for colorful background, she also committed herself to writing a School Story, or possibly a Boot Camp Story. Joan and Vanessa are Astronaut Candidates in the early 1980s. It doesn’t really seem like the 1980s: the book unfolds a dozen years after Stonewall, but it never seems to have occurred to Asst. Prof. Joan Goodwin that ...

(close)It is 1989, and the sleepy Austrian border town of Darkenbloom proceeds on its way, not yet knowing that history has not, in fact, ended. A stranger comes to town, looking for mass graves. A group of students come to restore the abandoned Jewish cemetery. The town physician, who has been there since his 1930s assignment to replace Dr. Bernstein, wants to retire. Dr. Alois, who used to be assistant Gauleiter, wants to do small favors and offer advice. And Farmer Faludi wants to build a big water tank is the disused Rotenstein meadow.

(close)A fine short biography of the philosopher who explored, among much else, the questions of whether language is complete: are there things that can be known but cannot be expressed in language? Wittgenstein had a knack for knowing people: at school, there was a boy a couple of classes ahead of him named Hitler. His brother Paul was a concert pianist, and when he lost an arm in the First World War he went right ahead an commissioned a repertoire of piano work for the left hand, a collection that would prove invaluable to Leon Fleisher when Fleisher lost the...

(close)Books Bought Lately: Recent additions to my reading stack, including review copies, loans, gifts.

All dates subject to change. Want to arrange a talk? Contact Eastgate . A list of some previous talks is here.

1183 Books: by author | by title

2021 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2020 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2019 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2018 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2017 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2016 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2015 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2014 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2013 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2012 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2011 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2010 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2009 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2008 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2007 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2006 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2005 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2004 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2003 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

2002 Fall | Summer | Spring | Winter

Jorge Arango, The Informed Life, November 2022

Em Short, Getting Started with Hypertext Narrative, April 2016

Alex Strick van Linschoten and Matt Trevithick, Sources and Methods (podcast), October 2014

James Fallows, “How You’ll Get Organized”, The Atlantic (July/August 2014)

Judy Malloy, "The History of Hypertext Literature Authoring and Beyond"

Claus Atzenbeck, "Hypertext Research", ACM SIGWeb Newsletter (Summer, 2008) (pdf)

Lawrie Hunter, "No Reason not to link", Information Design Journal + Document Design 13:3, pp. 229-237 (2005)

Jakob Klein, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (24 July 2005)

Linton Weeks, Washington Post (on eBooks; paywall)

D. C. Dennison, Boston Globe (on Eastgate)

Jim Whitehead, The Cyberspace Report

F. L. Carr, English Matters

Joe Lambert, Digital Diner

Jennifer Ley, Riding The Meridian

Susana Pajares Tosca, Hipertulia

Roberto Simanowski, Dichtung-Digital