| CARVIEW |

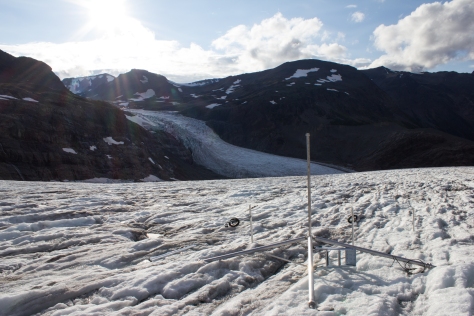

This was on mind when talking over the phone with Ben Pelto (University of Northern British Columbia). Those of you who have read other posts on this blog will know that Ben and I regularly work together during our summer fieldwork campaigns on the glaciers of BC (see On Conrad Glacier: Part 1 and Part 2). It was January, and we were discussing plans for a spring trip to the mountains, specifically Conrad Glacier, to observe how the winter had treated the glacier, and to scout out locations for the coming summer’s deployment of my weather stations. We were also planning to perform scans of the glacier using a ground penetrating radar (GPR), which would provide us with information on how thick the ice is, and the general shape of the underlying bed. This would all require some serious skiing.

Three months later, I am on a familiar road. With skis and camping gear in the back, I’m winding my way along the 750 odd kilometers from Vancouver to Golden, in eastern BC. Tonight, I’m meeting Ben and his sister, Jill, before an early morning helicopter flight to the ice.

After a brief delay to fix a clogged spark plug, we were in the skies above the Purcell Mountains, in good flying weather. It was my first time taking this journey in what were essentially winter conditions, and I was glued to the window as we maneuvered between the snow-covered peaks. We landed on the west flank of Conrad Glacier at 2,300m. Our campsite overlooked the jagged crevasses of the icefall that lay above our summer field sites. We dug out level platforms in the snow for our tents, and built up walls on the upper side to keep out the cold, downhill ‘katabatic’ winds that can develop on glaciers at night. In the front vestibules, we dug out lower platforms for storing gear, and putting on our boots in the mornings. Finally, we dug out a table and benches, and pitched a tarp over it to serve as our kitchen.

One of the main goals for this trip was to get an idea of how much snow the glacier had received over the winter, and how much water this snow will produce if it melts in the summer. To this end, we needed to take regular measurements across the glacier of the depth of this season’s snow, and its density. After setting camp on the first day, we skied down to the terminus of the glacier, and took a series of these measurements as we moved back up the slope. The weather was mild, and we were surprised to find a well developed melt water stream this early in the season, carving a channel into the surface snow. In the weeks preceding our trip, we had been keeping an eye on data from snow sensors located on mountains in this region. The early onset of spring was resulting in some significant snow melt, and the question on our minds was whether 2016 would prove to be as detrimental to the glaciers in this region as the record losses of 2015.

Late in the afternoon, with the weather beginning to turn, we pushed back to the shelter of our camp. After a warm meal, we watched the skies clear and felt the temperatures drop as the indigo twilight turned into a star filled mountain night.

Day two saw the beginning of our radar campaign. Our objective was to ascend to the upper plateau of Conrad, taking measurements along the way. The GPR system consists of a transmitter, and a receiver, each mounted on skis, with antenna extending out in between. The transmitter sends out a pulse of energy that passes down through the ice, and reflects off the bedrock underneath. The reflected energy is detected by the receiver, and the time taken by the pulse to travel to the bed and back tells us how thick the ice is. That’s the theory. The practical involves hauling this system over large swaths of the glacier, up steep slopes and icefalls, and around crevasses, trying to keep the system in line as much as possible. The relatively mild temperatures and strong sunshine made the hauling difficult, with the sleds prone to digging into the soft snow and tipping over. Despite this, we managed to cover significant ground with the radar, completing day trips of over 20km in some cases. Descending with the GPR was always an interesting experience, generally completed at the end of the day when we were returning to camp with already tired legs. We needed to act as brakes to stop the system from torpedoing down the mountain, requiring us to snowplow in our skis for kilometers downhill at a time, quad muscles screaming.

Our days on the glacier continued with combined snow depth/density measurements and GPR surveys. Working on the upper plateau of Conrad, the expanse of mountainous terrain around us was astounding. On every degree of the compass, snow covered peaks jostled for space on the horizon, like some jagged, storm blown ocean. A thought that keeps returning to me when working in these places, is what a privilege it is to be afforded such isolation and space in what is an increasingly crowded world. No traffic, sirens, voices, bleeping phones, or engines (apart from the occasional helicopter). To have access to the culture and community that living in a society provides is a great thing, but I am grateful for these opportunities to exist in solitude with nothing but survival and science to drive us on.

On one of our last days on the upper section of the glacier, we continued to record snow depth values to well over 3,000m elevation, and decided to push on to climb the summit of Mount Conrad; the peak which had loomed over us as we worked. We ascended on skies to within 50m or so of the 3,290 summit, before shedding our gear and scrambling the rock and snow of the final section. We climbed in beautiful weather (as had been the case for most of the trip; very unusual for Conrad), and our view from the summit was unimpeded in all directions. Turning from the summit, my thoughts were now fully occupied by the ski descent necessary to get off the mountain. The conversation I had had with Ben in January regarding my ski experience was echoing in my head as I clipped into my skis, and double checked my bindings. This was steep for me, but hesitating or leaning back would be the wrong option. I watched Ben and Jill drop in, took a solid breath, and followed.

Our spring visit to Conrad had been very successful, with a wealth of snow and ice thickness data recorded over much of the glacier. Throughout our travels , I had been scouting for potential sites for installing the weather stations in the summer; just two short months away. One would be deployed in a similar location to last year; lower on the glacier in the ablation zone (the area on a glacier where more ice/snow is lost than gained from year to year). The other would be a more ambitious venture. The upper plateau at 3,000m would provide a unique and intriguing location to gain information on the glacier’s weather and melt relationships. It would also present a much harsher environment to operate in. Would we get a decent enough weather window to allow us to install the equipment (several days work), and if so, could the system withstand a season in tough and, as of yet, untested conditions? We would find out soon enough.

]]>

Static. A build up of electrical charge induced by the clouds above. A precursor to a lightning strike. The noise is me; I’m buzzing, along with the metallic objects strewn around us. Stepping away from any potential lightning conductors, and slipping off my climbing harness with all its dangling metal, we wait for the clouds to pass us by.

It’s been quite awhile since I’ve sat down to write here, and a brief update was needed to bring things up to speed. Eight months have passed since our run in with the electrical storm on Conrad glacier, and much has happened in the interim. Conferences, comprehensive exams, trips home, film competitions. More importantly, 2015 was confirmed as the warmest year on record; taking the mantle from the previous record holder, 2014. Months before this was confirmed however, the evidence was showing itself to us in the mountains.

We had returned to Conrad Glacier in early September to dismantle the weather stations that had been in place all summer (see On Conrad Glacier: Part 1). They had been simultaneously recording the weather conditions and rate of ice melt over the season, in a hope to better understand what was powering the melt. Our party of 5 consisted of Ben Pelto, Brian Menounos, and Marzieh Mortezapour from UNBC, Clemens Schannwell (a visiting grad student from the University of Birmingham), and myself. The glacier greeted us with its usual box of atmospheric treats, alternating between showers of snow, hail, and rain, and the ever present katabatic wind. Camp was set on the rocky margins of the glacier, from where we would set out each morning to work on the stations and take measurements of how the glacier had responded to the summer.

I was delighted and greatly relieved to find both my stations operating when we reached them. As had been the case the previous year, I had no way to check on them over the two months since they had been installed on the mountain, and like an anxious parent, I’d had them on mind for much of this time. The data from Conrad (which is still being analysed), along with the observations by Ben on a series of glaciers in BC (and those from glaciologists throughout the region) told the story of what was the worst year for glacier loss since monitoring began.

The footage from the time lapse camera I had installed gives a clear impression of the speed of the melt, while only accounting for a portion (54 days) of what was a long melt season. The significant ice loss of summer 2015 made the Canadian news stations, with the footage appearing in CBC’s ‘The National‘, and on Global News television.

The end of the 2015 field season marked the beginning of preparations for my proposal defense, and is my main excuse for being absent from here for so long. Essentially, this process involves defining the final goals of your PhD, and convincing your supervisor and a panel of professors that you and your research are up to scratch, and that the project is worthwhile and moving in the right direction. Since getting over this hurdle, I’ve been working on my first paper, looking at the relationships between weather and melt on Nordic Glacier (see Notes from Nordic), and had a surprisingly successful entry into the NSERC Science Action film competition.

But the calendar, as always, has flicked around rapidly, and I am again preparing for the summer’s field campaign; complete with new challenges and objectives. All going to plan, this may well be the last campaign of my PhD. I hope to start posting frequently again, and to give brief updates on the science, why it’s relevant, and the life behind it.

Up Next: I’ve just returned from some spring field work on Conrad Glacier; spectacular conditions and views, but with ominous signs for the melt season ahead. Report coming soon.

]]>Four months earlier, I had returned to Vancouver from Svalbard, and an arctic winter that I will never forget. Touching down in YVR airport though, my mind was already on the list of ideas and tasks that would need to be tackled before fieldwork in July. My field campaign on Nordic Glacier last summer (see Notes from Nordic and Return to the Field) had been successful, but this season would present a whole host of new challenges. New glacier, new sensors, new objectives.

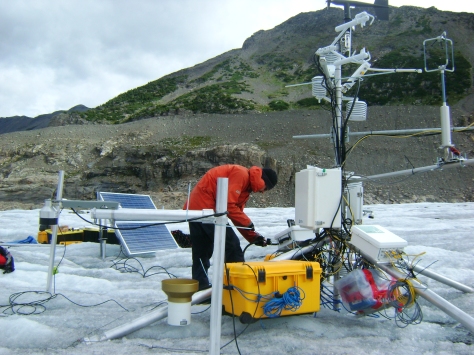

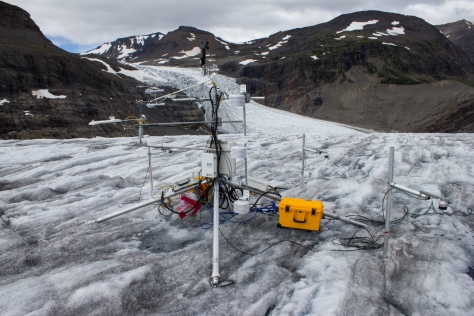

The overall goal of my project remains the same; to measure the weather conditions over a glacier surface, and to better understand how these conditions affect melt rates. One of the main differences for this year was that two stations would be installed on the glacier rather than one. The idea behind this is to see how weather and energy patterns vary across different points on the surface of the glacier, and how this in turn affects melting. This would mean a doubling of the number of sensors that would need to be prepared and tested.

One of the more challenging aspects of last year’s campaign was ensuring the station remained powered throughout the summer. The nature of mountain weather means that persistent cloud can prevent a solar power system from providing enough energy to the sensors. In addition to doubling the number of stations this year, each station was fitted with a new, power hungry system for measuring turbulent air flow (an important mechanism for transferring heat between the atmosphere and glacier). The upshot is that a total of 12 large boat batteries and 4 solar panels are required this time in the hope of keeping everything beeping and recording over the season.

This year’s destination is Conrad Glacier, in the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia. I had visited Conrad at the end of last season to scout it out as a potential research site. Aside from its scientific merits, it is a beautiful part of the world; flanked by snow covered peaks, with forested valleys below and miles without engines. Named after Conrad Kain, a pioneering Austrian mountaineer who unlocked several first ascents in this area, the glacier is one of many in this region at risk of total disappearance. A recent study has forecast a 70% loss of BC’s glaciers this century, with almost total deglaciation in this region. Apart from global consequences to sea level rise, the loss of a glacier is the loss of a large water reservoir, putting pressure on ecosystems and communities (who use the water for drinking, irrigation, and hydro-power) during dry periods like we’ve had here this summer.

Being just a short journey south from last year’s glacier (Nordic), we would again base ourselves in the town of Golden prior to our flight into the mountains. After spending a day on the always spectacular drive from Vancouver to Golden, Valentina and I met up with Ben, a glaciologist from the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC) who would be joining us. Over some excellent burgers, we also had the chance to catch up with Tannis and Steve, friends of ours who run a ski lodge in the area, and have been consistently helpful. The plan for the next day was to drive to a staging area in the foothills to the south of Golden, and get all our gear into the mountains in as few chopper loads as possible (with thanks as always to Steve for his expertise on this).

Three helicopter flights (and some delays) later, all crew and equipment were accounted for on Conrad. Our campsite was just off the ice itself, on a rocky outcrop overlooking the glacier. The first evening was a battle against the weather to get tents set up in between heavy showers and gusty winds. Dinner was a simple affair, with everyone retiring to their sleeping bags early; sleep coming to the sound of fluttering tent fabric.

After breakfast the next morning, we set about finding the best route from camp on to the glacier; navigating the broken and crevassed ice along the glacier margin. Two locations had been selected for station 1 and 2 not far from camp. Each station would take about two days to install, with some additional time to prepare and secure everything for a season in the mountains.

The weather had a constant presence throughout the week, with wind, thunder and snow storms slowing the work somewhat, and making cooking a frigid task at the end of the day. Despite what felt like a cold spell to us, it was clear as soon as we saw the glacier that it was experiencing a warm season. In combination with low snowfall during the winter, warm temperatures had resulted in significant melt across the surface by the time we had arrived. Although close to what would normally be the beginning of the melt season, this year’s snow had already completely melted up to the high regions of the glacier.

With the stations coming together, Ben and I ventured higher up the glacier, and spent an afternoon installing ablation stakes. These stakes, installed along the length of the glacier, provided a record of how many meters of ice are lost or gained at the surface each year, and give an indication of the health or mass balance of the glacier (see Svalbard Part 2: Balancing Act). During the week on Conrad, Ben was also involved in carrying out a kinematic survey; using detailed GPS measurements to create a map of the glacier.

Due to weather delays, the final tasks for installing the stations were completed in the last few hours of the trip. With the helicopter due to pick us up that afternoon, I got moving early on the last day, and headed on to the ice before dawn to shore up the last few pieces of equipment from the elements, and to make sure all the systems were behaving. In the end, two full weather stations were installed, along with a time lapse camera to monitor conditions over the season.

It remains to be seen how the the glacier will respond to this year’s melt season, and on a personal level, how all the equipment will perform. A good or bad field campaign will have a major impact on the timeline for my studies and on the goals I hope to achieve. As our chopper lifted off from our disassembled camp and sped down the valley, I took one last glimpse at the stations and the glacier itself, before my eyes turned to home and my mind to the plan for the next trip.

A Note of Thanks: Just prior to leaving for field work, I received word that I was being awarded the Chih-Chuang and Yien-Ying Wang Hsieh Memorial Scholarship for research in Atmospheric Science. A sincere thank you to the Hsieh family. I was honoured to received it.

UP NEXT: The return to Conrad, and what we found.

]]>Professor Doug Benn is recounting to us his reply to a reviewer who questioned his use of the term ‘refrozen water ice’. While this may sound superfluous, the many variations in density, temperature, content, layering, and colour of glacier ice can tell us a lot about its history, and potentially, about it’s future.

]]>

When ice and snow on the surface of a glacier melts, it can produce a lot of water. Streams of this meltwater flow over the surface of a glacier during the warmer months of the year. These streams can cut or ‘erode’ into the glacier, creating paths or channels which the water flows through. Over time, these channels can cut deeper and deeper into the glacier, their roofs closing over to create tunnels through the ice which can bring the meltwater from the surface all the way down to the bottom of the glacier. This is important because increasing the amount of water underneath a glacier can encourage it to slide faster.

During the cold winter months, melt channels are generally dry. We had explored one of these channels previously on Scott Turnerbreen (see Svalbard Part 2: Balancing Act), and decided that some more time under the ice was needed. There had been reports of an excellent ice cave on Larsbreen, a glacier within an hour’s hike of Longyearbyen. So one Tuesday evening, with duties at UNIS finished for the day, Tom, Ellie, Jelte, and myself met on the outskirts of the village, and began the trek to the glacier. Our plan was to explore the cave for a few hours, and then being a bunch of idiots, to stay overnight inside the ice.

(A note on the images: the caves in the glacier were entirely dark, with our headlamps being the only source of light. Therefore, for me, much of the photography was experimental; playing around with shutter speeds, iso settings, and flashes, while avoiding damaging my camera too much when climbing and crawling. As always, click on images to see them in full resolution)

By the light of the moon, we found the entrance to the cave; first squeezing into a tunnel down through the overlying snow to get into the glacier itself. The passage through the ice twisted, widened, and narrowed, like a desert rock canyon; in sections coated in fragile crystal structures, then changing to smooth, swirled patterned walls like polished marble. We followed the channel as far as we could go, descending through a series of levels and passages until we were forced to stop at a major drop; the location of what would have been a waterfall during the melt season. We picked a spot where we could roll out our bags for a few hours, and returned to the surface for some frigid air before sleep. On the way to the surface, I had a ‘how did I get here’ moment; crawling out of a glacier through a snow tunnel in the middle of the night, with a rifle on my back to watch out for polar bears, and being greeted by the northern lights.

Our night in the glacier was a memorable experience, but it felt like the caves had a lot more to show us had we been willing to push a little further. A few days later, we returned to Larsbreen. Armed with ice climbing gear, Tom, Andi, and myself would attempt to work our way down some of the larger drops that had stalled us on the previous visit, and see how deep we could get.

We found the bed of the glacier, and it was an awe inspiring experience to have this entire mass of ice lying above us. My thanks to my like-minded companions on both trips for their company; the highlight of being in such incredible places is to share it with great people.

]]>When a ray of sunlight was spotted hitting the mountain tops on the other side of the fjord, it was decided that a group of us would aim to get as much elevation as possible over the weekend, and try to catch some elusive light. Temperatures would remain well below -20°C over the two days, so warm clothes and moving fast would be essential.

Saturday morning saw us hiking up to Sverdruphamaren; an elevated plateau to the west of Longyearbyen. There is a real sense of wilderness here, and the view is an expanse of white peaks, sea ice, and reindeer. The sun however, remained just below the higher mountains to the south.

On Sunday morning, we aimed higher, and set out for Trollsteinen; the peak behind which the Sun had hidden from us the previous day. With temperatures at sea level forecast to be around -30°C, we knew we were in for a cold summit. Our route would bring us south of Longyearbyen, up the glacier of Larsbreen, before ascending onto the main ridge of the mountain. The winds were calm, and the skies were perfectly clear, promising excellent views, and potentially some vitamin D.

The Sun is literally days away from reappearing here in the valley, and the community of Longyearbyen will mark its return this weekend with a festival in its honour. It’s certainly something worth celebrating, but I’ll still be happy to experience a few more Svalbard nights.

]]>

The measure of the growth or shrinkage of a glacier is known as its mass balance, and this was the area of focus during my first week here in Svalbard. As part of the glaciology program I’m involved in, we traveled to one of the local glaciers to examine the layers of snow on its surface, and to hopefully explore some of its inner workings. Named (somewhat ironically) after a local coal mining manager in the early 1900’s, Scott Turnerbreen is located in a valley to the south east of Longyearbyen.

Glaciers are formed where snow is able to build up over time, and gradually get squeezed or compressed into ice by the weight of the snow on top. The growth of a glacier is essentially a balance between how much goes in i.e. snow, and how much goes out i.e. melting. If more snow and ice is added to a glacier than is melted, the glacier grows; if more ice melts than is replaced by snow, the glacier shrinks. Think of it as a bank account; lodge more money than you withdraw, and your account grows, and vice versa. Warmer climate conditions have increased melt rates on glaciers, removing ice faster than it can be replaced by snowfall.

On Scott Turnerbreen, we carried out a number of surveys of the snowpack. Firstly, we used snow probes (basically long tubular measuring sticks) to determine the depth and pattern of snow accumulation over the surface. We then dug a series of snowpits to examine the thickness and density of layers in the snow, and to look for evidence of a recent ‘warm’ weather spell. That was, of course, until getting completely distracted by a passing group of dog sleds. When in the Arctic.

Our attention then turned from the surface of the glacier to deeper into its core. In order to gain access to the inner glacier, we descended down through a presently dry meltwater channel. Like a scene from a Jules Verne novel, we traveled through a subsurface tunnel of ice with incredible formations and patterns. This was a brief visit, but I’m hoping to return to these passages while I’m here, and spend a little time to get some images that do them justice.

Up next: Exploring the surrounding mountains in the search for sun.

]]>My destination is Svalbard; an archipelago of islands in the Arctic Ocean. I’m taking part in a glaciology program run by the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), which is located in the regional capital of Longyearbyen. Sixty percent of Svalbard’s surface is covered by glaciers, making it an ideal location to study their processes.

The first leg of my journey takes me from Vancouver to Oslo, where I have an overnight stay before my flight to Longyearbyen. The stopover gives me a chance to join up with a friend who is also taking part in the glaciology program. I met the aptly named Aurora last summer in Alaska (see North to Alaska), and catching up over some much need food that night, we’re both equally excited about the trip ahead. The next morning, we soak up the last sunrise we’ll see for a few weeks, and board our flight to the Arctic.

Arriving in Longyearbyen just after 1pm, the usual bustle for hand luggage when the plane stops takes on a more practical air. Down jackets, balaclavas, and mittens are being pulled on before the exit door is opened. Stepping out into the blue semi-darkness, we are greeted by a biting wind that draws streams of fine snow across the tarmac. It’s already below -20°C, and I couldn’t be happier.

The following are just some initial shots from my first few days here, including some from the training we underwent. As always, images can be clicked on to view in full size. More updates coming soon.