| CARVIEW |

To register for the source, follow this link.

Developed out of my yearly course on medieval Jewish theology at Yeshivat Orayta, the four classes will each explore a different topic in which medieval philosophy and theology can provide a new vantage point from which to look at issues vexing contemporary life, Jewish and otherwise.

Here is the official course description:

What can medieval Jewish philosophers teach us about today’s deepest dilemmas? In this four-part series, we’ll explore how the great thinkers of the medieval Jewish tradition—Maimonides, Saadia Gaon, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, and others—grappled with questions that remain urgent today: Can science and Torah both be true? Is tradition still trustworthy in a skeptical age? What does it mean to live a good life? And how do we respond when the Torah seems morally troubling? Analyzing these texts together, we will see how these classic voices offer bold, surprising answers to the challenges of modern faith, identity, and ethics.

The four questions in the description make up the structure of the 4-part course:

- Torah and Truth (with science as a stand-in)

- Tradition, Skepticism, and Conspiracy Theories

- Visions of the Good Life (secretly by Alasdair MacIntyre)

- Torah and Morality and History and Progress

I am really looking forward to talking about these ideas with a new audience and seeing what people make of them.

Classes will be every Tuesday @ 12:30 EST. The four classes are complementary, but you don’t have to come to all of them. If any of them sound interesting to you, please join in!

To register for the source, follow this link.

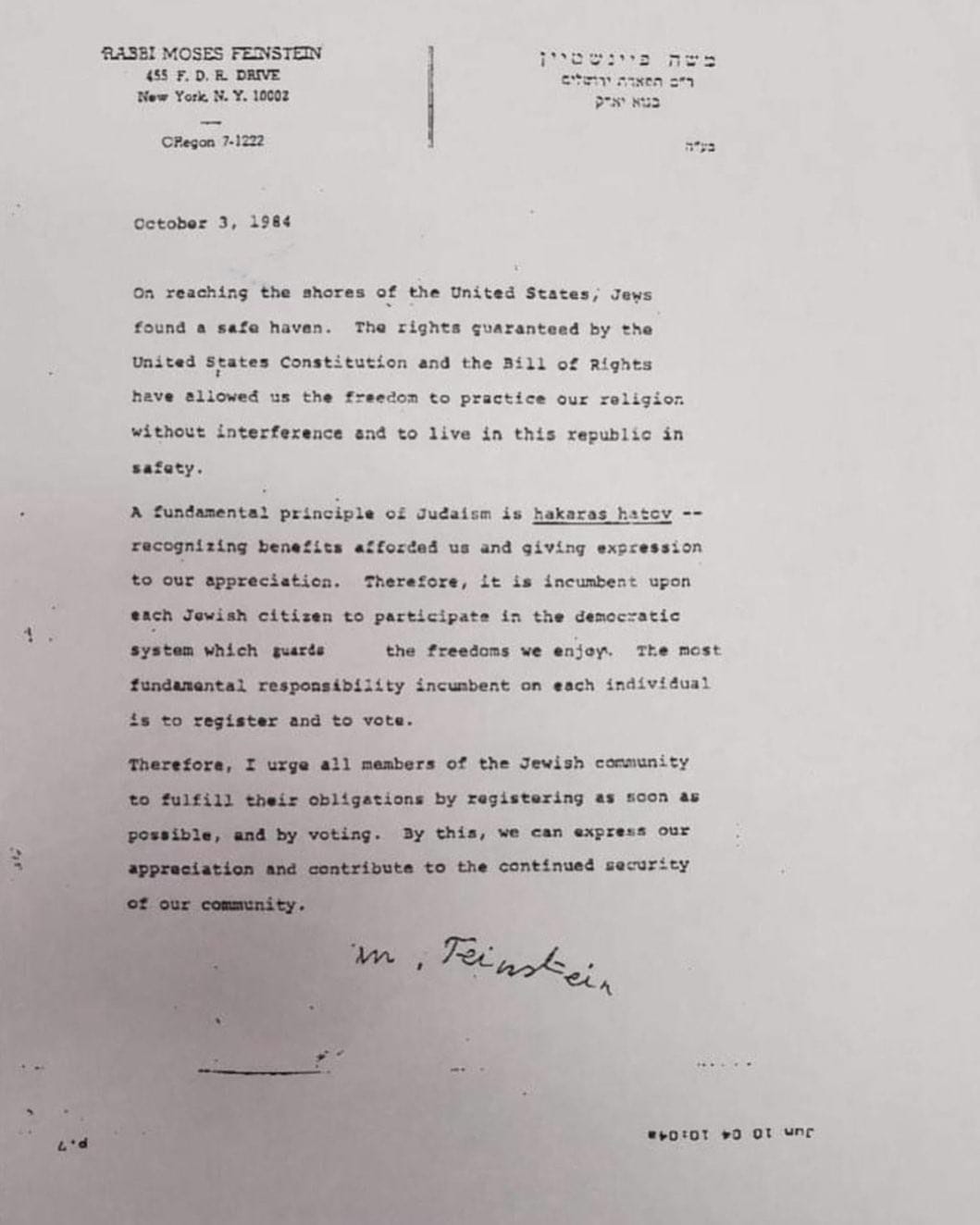

]]>First, the letter itself. Here is an image of the letter:

And here is a digitized version of the body of the letter:

On reaching the shores of the United States, Jews found a safe haven. The rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights have allowed us the freedom to practice our religion without interference and to live in this republic in safety.

A fundamental principle of Judaism is hakaras hatov — recognizing benefits afforded us and giving expression to our appreciation. Therefore, it is incumbent upon each Jewish citizen to participate in the democratic system which guards the freedoms we enjoy. The most fundamental responsibility incumbent on each individual is to register and to vote.

Therefore, I urge all members of the Jewish community to fulfill their obligations by registering as soon as possible, and by voting. By this, we can express our appreciation and contribute to the continued security of our community.

Against Instrumental, Parochial Reasons for Voting

The key reason this letter is invoked is because it provides a non-instrumental reason to vote—something more principled that “make sure you get yours!” (or rather, “make sure we get ours”). The last line does carry a more instrumental melody—“and contribute to the continued security of our community”—but this is shockingly absent throughout the rest of the letter. This is particularly true when contrasted with other Orthodox authorities attempts to encourage voting, which fall entirely within the instrumental range. See, for example, the letters collected here by the Agudah. The only other one to mention a non-instrumental reason for voting is the one from the moetset of the Agudah in 2008, in which it feels like an afterthought after the primary, instrumental reason, and where it is clearly downstream from Rav Moshe’s letter.

In contrast, Rav Moshe gives instrumental reason a clearly secondary status. His primary reason is “hakaras hatov”—gratitude—which is underlined in the original text of the letter. His letter expounds upon the spiritual and material flourishing of the Jews in the US and how that flourishing is directly tied to the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Sure, voting can help the Jewish community secure its own interests, but more importantly: it is how the Jewish community can properly show its gratitude to the country for making it possible to lead safe, secure lives in line with the dictates of Orthodox halakhah.

Thank God for US Liberalism

It is worth noting how he very clearly and specifically envisions the US as a liberal state (liberal in the political-philosophy sense, not the partisan sense). This is a broader theme in Rav Moshe’s writings. In a derashah he gave for the Shabbat Zakhor of 1939, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the US Constitution, he said that America had “enshrined in its law that it does not maintain any particular faith or ideology, and that each person can do as they will” (Darash Moshe, vol. 1, 416). This is in contrast with the totalitarian governments of Germany and Russia, and with Amalek—whom he characterizes in the derashah as specifically illiberal, attempting to enforce ideological conformity through violence (see my previous post on this aspect of the derashah). Figured as a sort of Anti-Amalek, the US makes flourishing Jewish life possible by creating space for any and all non-violent ideologies and systems of belief.

This is a key feature of the US for him, and he mentions it regularly. In a letter about non-Jewish prayer from 1963, he remarks that “the Lord’s Prayer” said in US schools is not problematic for Jews, in part because “the rulers of our country are men of kindness (anshei ḥesed), and they do not want to impose their religion upon the other citizens—therefore they established the text that they did” (Igrot Moshe OH 1:25). The unique ḥesed of the US is tied to how it enables the Jews to flourish as Jews without imposing on them some other religion or restricting their Jewish observance. Intervening in then-ongoing debates about prayer in schools, with most Jewish organizations opposing the practice, Rav Moshe says that it is fine because the US government is fundamentally multi-cultural.

Similarly, the one letter where Rav Moshe does use the phrase “malkhut shel ḥesed” (lit., “kingdom of kindness”) to refer to the US (Igrot Moshe HM 2:29) is about how the US grants funding to all educational institutions in the country—including Jewish schools teaching their students Torah! The Jews are beneficiaries of this liberal environment—not to mention the welfare state—where instead of compelling education for a specific belief system, or even just only supporting that one belief system, the US government actually supports education for all kinds of different belief systems. Because it maintains what political philosophers call “liberal neutrality,” the US creates a welcoming environment in which Jewish life can flourish and perpetuate itself.

Notably, Rav Moshe does not see this as merely a happy accident. In the speech for the anniversary of the constitution, he says that in creating a liberal society, “they are acting in accordance with the will of the Holy One, blessed be He.” US liberalism is itself a fulfillment of the will of God (!). Moreover, the Jews’ arrival on American shores was an act of divine providence, as he says in his letter about state funding: “The Holy One, blessed be He, in His abundant mercy upon the remnant that survived from among the Jews of all the lands of Europe… brought us here.” God brought the Jews to a liberal state with significant welfare programs which encourage the flourishing of all religions in a pluralistic manner. This theological affirmation of US liberalism is the background for Rav Moshe’s articulation in his letter on voting that life in the US is something for which Jews should express gratitude.

Before expanding on the relationship of voting and gratitude, I should note that Rav Moshe is not simplistically rosy-eyed about the liberal environment in the US. In a 1979 responsum about how doctors should behave on shabbat and whether or not they should violate shabbat in order to save a non-Jew, he suggests that US liberalism actually heightens the pragmatic necessity of doing so (Igrot Moshe OH 4:79):

Given the situation in our countries today, hostility (eivah) poses a serious danger—even in countries where Jews are generally allowed to live according to the laws of the Torah—since in any case it is unacceptable that, on that basis, one should refuse to save a life.

The liberal environment of the US is a double-edged sword. The permissiveness of US government when it comes to ideological and religious multiculturalism does not extend to risk to life. In fact, Rav Moshe sees the purpose of states as protecting life (in a minimal sense; see the constitution derashah), so allowing religious beliefs to take precedence over saving a life would contradict their very purpose.

Moreover, the liberal environment also means that freedom of the press is a fact with which Jews must contend. In the continuation of the letter, he argues that the combination of free press with advanced information and communication technologies mean that eivah is always a concern, because actions by Jews in any one place could lead to antagonism against Jews anywhere else.

But in our time one must, it seems to me, be concerned about danger in every place; and also because of the dissemination of information through newspapers, immediately whatever is done anywhere in the world, there exists the stumbling block of learning from place to place, and also incitement to increase hatred to the point of murder is great through this. Therefore it is clear that in our time this must be judged as an actual danger, and it is permitted when such a case arises.

The expectation of liberal multiculturalism is reflected in the government, but ultimately permeates all of society. Living in the US therefore constitutes a historical gift to the Jews, but also brings with it its own strictures and standards. On balance, however, this is not really so different from the past—in some ways, this is Rav Moshe’s point in the responsum. There was always a concern for hostility from non-Jews on this point, and in a liberal society, that still exists, even if some of the dynamics are different. Despite that, life in the US still clearly represents a historical step forward for Jews, and for that they should be grateful.

Gratitude for Liberalism

This brings us to the issue of the relationship between gratitude and authority. Rav Moshe’s basic argument in his 1984 letter is that the gracious use of power for a person’s sake engenders a responsibility to show gratitude.

In context of Rav Moshe’s letter, it is very clear that the gracious use of power in question is the creation, maintenance, and enforcement of US liberalism. The US creates a liberal, pluralistic space in which Jewish communities can flourish, in ways we can call both positive and negative. In a “negative” sense, the US avoids establishing any one religion as the religion of the land. Even if it is in some sense a Christian country (there’s a Christian majority, it was founded by Christians, etc.), the US’s governing institutions refrain from treating Christianity as if it were the law of the land. In this way, it enables non-Christian—and even Catholic—communities to flourish.

In a “positive” sense, it grants funding to Jewish educational institutions alongside all other educational institutions. It is committed to equal access to education and providing the funding for such education, including in some ways to religious education. This combination of multi-cultural liberalism and the welfare state yields a truly remarkable situation for the Jews, one for which they should rightly show gratitude.

This gratitude is gratitude to the state. The Jews should see themselves as having received something of value from the state and as therefore bearing some sort of obligation toward it, if not exactly a debt. They should discharge this obligation, Rav Moshe says, by participating in the democratic process. Voting is not an inherent good, on this model, but something that gains value by virtue of being valued by the state.

This is, to put it mildly, a somewhat strange way to think about democratic governance. I’ll address that, hopefully, in a future post.

]]>Note: the artwork for this post is from S Ilan Block.

School Prayer in the US in 1963

Rav Moshe’s letter is dated January 1st, 1963 (or rather, the 5th of Tevet, 5723, the corresponding Hebrew date). This puts it right in the middle of an ongoing legal and cultural firestorm in the US: the debate about school prayer. Historically, some form of prayer had been common in most US public schools. The previous year, in 1962, the US Supreme Court ruled that the New York “Regents’ Prayer” violated the constitutional separation of Church and State, and so could no longer be said in public schools. In June of 1963, a further Supreme Court ruling would rule saying the Lord’s Prayer and readings from the Bible in schools unconstitutional as well.

Rav Moshe’s letter comes right in between these two pivotal rulings, which many Jewish organizations felt it necessary to weigh in on. In the US, “school prayer” really meant “Christian prayer,” so many Jewish organization supported the legal campaigns trying to end the practice. (One notable exception: The Lubavitcher Rebbe. See this excellent article on the topic by Tamara Mann Tweel.) Even after the Regents’ Prayer was ruled unconstitutional, the fights about it, and related practices, continued throughout US civic society.

Rav Moshe’s Letter

This is the context in which Rav Moshe wrote his striking responsum letter (published in Igrot Moshe, vol. 4, OH §25), in which he explicitly comes out in favor of keeping the Regents’ Prayer in school. I initially thought he was talking about the Lord’s Prayer, which would be a way more radical claim, because his letter post-dates the SCOTUS ruling on the Regents’ Prayer, but it is very clear from his description of the prayer said in schools that he has in mind the Regents Prayer, which reads: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our country. Amen.”

The claims he makes about the prayer are striking nonetheless. The responsum begins with a few theoretical paragraphs about the obligation of non-Jews in prayer before pivoting to discuss the ongoing US cultural drama. I have not reproduced those first paragraphs in the translation below, focusing instead on those relevant to Rav Moshe’s political theology of the US.

Perhaps the most important point he makes in for this topic—and what first brought me to look at this letter—is his claim that the members of the US government who composed the prayer undoubtedly did so with no desire to enforce Christianity on any students. Rav Moshe sees the US as a blessedly liberal state which intentionally fosters and makes possible a multicultural society. Therefore, the prayer should not be seen as any form of Christian prayer being forced on the students.

This is why, while he ultimately says that it is better for the Jews to stay out of the public controversy because there are good arguments on both sides, he also says that his opinion is that the Regents’ Prayer should be kept in schools! He doesn’t want to intervene in the fight, but he does have a side he wants to see win.

Most striking to me on a traditional and halakhic level, however, is his claim that Jews saying the Regents’ Prayer in schools could fulfill their biblical obligation to pray by doing so. The essentially non-Jewish prayer, because it does not explicitly reference idolatrous beliefs or practices, can function as part of a life of Jewish obligation. (Presumably, he was imagining that this way non-Orthodox Jewish students who wouldn’t otherwise pray would at least fulfill their biblical obligation.)

He also makes a detailed argument that silent, purely non-verbal prayer has no halakhic significance whether for Jews or non-Jews, so people who propose a moment of silence as a replacement for school prayer are fundamentally mistaken. I would have skipped this part in my translation, but I found it striking because the Lubavitcher Rebbe would eventually be one of the people making that argument (see Tweel’s article linked above)! I don’t believe he was already arguing it then (Social Vision says he only started campaigning for it in the 80’s), but either way, the contrast made me want to include that section.

Without further ado, the translation of (the second half of) the letter is below.

Translation of Igrot Moshe, vol. 4, OH §25

With regard to the short prayer that children recite in public schools, it appears that the wording was deliberately crafted so as not to include any reference drawn from the sacred texts of their own faith. This is because the schools were established for Jews and for members of other religions as well, in our great country, and the rulers of our state are people of kindness (anshei ḥesed) who do not wish to impose their faith upon the other citizens. For this reason they instituted such a formulation. Accordingly, there is no basis for concern that this prayer was composed by clergy with the intent of directing participants toward their religious beliefs. Therefore, there is no prohibition here as a matter of law, nor is there any concern arising from how this appears to observers—even if one were to argue that praying together is problematic—since in this case it is clear that no such concern exists, because it is known that each participant intends the prayer in accordance with his own faith.

As for mentioning the name “God” in English, referring to the blessed Holy One, with one’s head uncovered, it does not seem necessary to be particularly stringent. For the Shakh (Yoreh De‘ah 179:11) writes that a divine name written in a secular language—such as in a bill of divorce—is not considered a divine name at all and may be erased, and this is so obvious to him that he even says, “consider it yourself,” since it is permitted to erase a name written in a secular language. On this basis, he even permits whispering an incantation over a wound and spitting while reciting a verse in a foreign language, even if God’s name is mentioned in that language, as Rashi reports in the name of his teacher—though he notes that ideally one should be cautious. See there. All the more so, then, with regard to mentioning God’s name with one’s head uncovered, since some authorities maintain that even mentioning the actual divine name uncovered is only a matter of pious practice. This is also implied by the language of the Shulḥan Arukh (Oraḥ Ḥayyim 91:3), which states the prohibition in the form of “some say,” indicating that it is not universally accepted. Certainly, one should not be stringent when this is impossible, as in the case of children in public schools who do not wear yarmulkes. There is therefore no objection to their mentioning the name “God” in English, and on this basis they would even fulfill the biblical obligation of prayer, since the wording was not composed by clergy.

As for a Noahide, who receives reward as one who is not commanded yet acts voluntarily when he prays: if he prays only in thought [this is comparable to] the case of a Jew does not fulfill the obligation through mental prayer alone, as stated in the Magen Avraham (Oraḥ Ḥayyim 101:2). It is therefore obvious that since he is not performing the act of the commandment properly, even a Noahide would receive no reward at all. Even though a sick person may contemplate the prayer in his heart, this is only as an expression of the matter, and he does not fulfill the obligation through this; if he later recovers, he must repeat the prayer, according to most later authorities (see Mishnah Berurah 62:7 and the Bi’ur Halakhah there). Therefore, those who propose that prayer be arranged through silent contemplation accomplish nothing.

As for the concern that non-Jews might introduce explicit reference to their own beliefs into the prayers, there is no reason for such concern, since the formulation was deliberately established in this way precisely because there was no desire to impose any particular faith. This is the halakhic conclusion.

As for becoming involved in the dispute among the citizens of the state over whether this prayer should be recited in public schools or abolished altogether — my advice is that those who fear God should not involve themselves in this matter, even though there are those who maintain that we ought to intervene and state that our position is that the prayer should be recited. There are valid considerations on both sides, and therefore inaction is preferable.

]]>People who want to see my interpretation can check out the link above—I don’t think it has shifted too much in the intervening years. Here, I want to talk about how it is interpreted by Rav Soloveitchik, the key role he gives the Anshei Kenesset Hagedolah in his communitarian political theology, and the shift his interpretation undergoes when he shifts into a nationalist mode.

Naming the Men of the Great Assembly

Here’s the Aggadah (text and translation taken from Sefaria):

דְּאָמַר רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי לָמָּה נִקְרָא שְׁמָן אַנְשֵׁי כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה שֶׁהֶחְזִירוּ עֲטָרָה לְיוֹשְׁנָהּ

אֲתָא מֹשֶׁה אָמַר הָאֵ׳ל הַגָּדוֹל הַגִּבּוֹר וְהַנּוֹרָא

אֲתָא יִרְמְיָה וַאֲמַר גּוֹיִם מְקַרְקְרִין בְּהֵיכָלוֹ אַיֵּה נוֹרְאוֹתָיו לָא אֲמַר נוֹרָא

אֲתָא דָּנִיאֵל אֲמַר גּוֹיִם מִשְׁתַּעְבְּדִים בְּבָנָיו אַיֵּה גְּבוּרוֹתָיו לָא אֲמַר גִּבּוֹר

אֲתוֹ אִינְהוּ וְאָמְרוּ אַדְּרַבָּה

זוֹ הִיא (גְּבוּרַת) גְּבוּרָתוֹ שֶׁכּוֹבֵשׁ אֶת יִצְרוֹ שֶׁנּוֹתֵן אֶרֶךְ אַפַּיִם לָרְשָׁעִים

וְאֵלּוּ הֵן נוֹרְאוֹתָיו שֶׁאִלְמָלֵא מוֹרָאוֹ שֶׁל הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא הֵיאַךְ אוּמָּה אַחַת יְכוֹלָה לְהִתְקַיֵּים בֵּין הָאוּמּוֹת

וְרַבָּנַן הֵיכִי עָבְדִי הָכִי וְעָקְרִי תַּקַּנְתָּא דְּתַקֵּין מֹשֶׁה

אָמַר רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר מִתּוֹךְ שֶׁיּוֹדְעִין בְּהַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא שֶׁאֲמִתִּי הוּא לְפִיכָךְ לֹא כִּיזְּבוּ בּו

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: Why are the Sages of those generations called the members of the Great Assembly? It is because they returned the crown of the Holy One, Blessed be He, to its former glory. How so? Moses came and said in his prayer: “The great, the mighty, and the awesome God”(Deuteronomy 10:17). Jeremiah the prophet came and said: Gentiles, i.e., the minions of Nebuchadnezzar, are carousing in His sanctuary; where is His awesomeness? Therefore, he did not say awesome in his prayer: “The great God, the mighty Lord of Hosts, is His name” (Jeremiah 32:18). Daniel came and said: Gentiles are enslaving His children; where is His might? Therefore he did not say mighty in his prayer: “The great and awesome God” (Daniel 9:4).

The members of the Great Assembly came and said: On the contrary, this is the might of His might, i.e., this is the fullest expression of it, that He conquers His inclination in that He exercises patience toward the wicked. And these acts also express His awesomeness: Were it not for the awesomeness of the Holy One, Blessed be He, how could one people, i.e., the Jewish people, who are alone and hated by the gentile nations, survive among the nations?

And the Rabbis, i.e., Jeremiah and Daniel, how could they do this and uproot an ordinance instituted by Moses, the greatest teacher, who instituted the mention of these attributes in prayer? Rabbi Elazar said: They did so because they knew of the Holy One Blessed be He, that He is truthful. Consequently, they did not speak falsely about Him.

Founders of the A-Political Mesorah Community

One of the key places Rav Soloveitchik interprets this text is in the first half of Halakhic Morality (Maggid, 2017), where he reads the beginning of Pirkei Avot as reflecting the rabbis intentional recreation of the Jewish community after the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash and the loss of Jewish sovereignty.

While biblical Israel associated the community ideal with concrete forms of political or social existence, the Jews of the Second Commonwealth were steeped in a new community whose experience was separated from the political one. The concept of kahal, congregation, was sublimated and transposed into that of edah, community, uncanny communion with the bygone and the anticipated. Exile is always a menace to a kahal, never to an edah. The Men of the Great Assembly marked the beginning of a new phase in Judaism, a turning point in our self-consciousness. We became cognizant of our unity as a masorah community even while lacking all external social-political concomitants…

The central theme of this passage [our aggadah –LM] is that the Men of the Great Assembly formulated a new concept of heroism. While Jeremiah and Daniel equated “mighty and awesome” with physical might and heroism, military victory and political sovereignty, the unknown Men of the Great Assembly brought forth the idea of ethico-spiritual heroism, which expresses itself in a determination to exist in a unique way, in an awareness of a paradoxical modus existentiae, in a strange faith, in an almost absurd historical destiny, and in the courage to live in solitude, misunderstood and ridiculed by others. This type of fortitude was displayed by our ancestor Abraham and is the cornerstone of our historic experience…

The new concept of community asserts itself in the saying “Hevu metunim ba-din,” for if the Jewish form of existence is to be equated with the political community, then power would be desirable and commendable. All political philosophies—from the ideology of the corporate state to that of the democratic republic—operate with one premise: power as a positive value, which is to be cherished and appreciated. People aspire for the attainment of power. Such a yearning is a logical consequence of our political philosophy, regardless of its ideological strain. The Men of the Great Assembly, in conceiving and formulating a new type of community—the edah—broke with this tradition and destroyed the halo which surrounded the ruler and the king. In their stead appears the scholar, the rabbi. (HMo, Excerpts, 31–32, 34)

On this interpretation, the Anshei Kenesset Hagedolah are responsible for founding/refounding the Jewish community as a community, rather than a polity. They are ground zero for a vision of Jewish life and continuity focused on education close social ties and shared values passed on through teaching—both explicit and role-modeling. Exile is therefore not strictly a tragic political condition to be overcome, but the very condition that allows the rabbis to reimagine and revitalize the Jewish community. This is in opposition to a political community. Historically and homiletically, Rav Soloveitchik associates this with the Sadduccess who, he says, tried to maintain the Jews as a political community in opposition to the rabbinic communitarian project.

This opposition between community and education, on the one hand, and politics and power, on the other, is rampant throughout Rav Soloveitchik’s writings. One timely example is a derashah titled “Hanukkah Everlasting” from Days of Deliverance where he says that if Hanukkah was actually about military victory or political sovereignty, then it would have disappeared when the Jews eventually lost those. Instead, it was about cultural independence and persistence, and therefore it is eternal—exactly thanks to the rabbinic project described in his interpretation of our Aggadah.

Founding the (A)Political Nation

This is part of Rav Soloveitchik’s communitarian political theology which, as I said, appears rampantly throughout his writings. However, there is a subterranean nationalist streak which makes itself known here and there (this will be the topic of the last chapter of my dissertation). Perhaps the most direct example of this is a Yiddish derashah he gave in 1948 published for the first time just a few years ago, titled, “Jewish Sovereignty and the Redemption of the Shekhinah” (English translation available on Tradition’s website). The derashah is incredibly rich and I couldn’t possible cover it all here (I discussed some key aspects in a recent paper at Yad Ben Zvi’s “Kabbalah and Modernity” conference, and the video recording of that should be up on YouTube before too long).

In the context of discussing the vicissitudes of Kenesset Yisrael, the historical and metaphysical Jewish people, he returns again to our Aggadah and gives an interpretation that is initially the same as the one in Halakhic Morality, but which then makes a hard right-turn.

Jewish political power was wiped out and the Knesset Yisrael was condemned, suppressed, and decimated. With so many battles, political defeats, and military losses, it would have been self-deception to attribute heroism to Jewish existence in exile… The Men of the Great Assembly responded: on the contrary! They came and created a new concept of nationality, as well as a new idea of heroism, one of reverence and sacrifice. Knesset Yisrael is a nation not only through political-social community, not only through political sovereignty, not only through a large army… but also by embodying a definite Torah ideology, by fighting for a particular world order, by observing laws and judgments, by identifying with the Shekhinah. Heroism is sometimes demonstrated not only on the battlefield, but also in day-to-day life, in a stubborn fight for the realization of definite values, of creativity, and existence despite the obstacles…

And when did the Men of the Great Assembly create the new idea of a historical and politically transcendent Shekhinah nation? It is precisely when Jews had, through the grace of Cyrus, built their own kingdom and built it with self-sacrifice and heroism. It was precisely at that time when the Men of the Great Assembly proclaimed this new Shekhinah nation. Indeed, we must have a state, as well as a legal-political nation with all its accoutrements, for the state and the nation will serve as the laboratory in which the great ideals and values of the political nation and values of “great, mighty, and awesome” will be realized. The Men of the Great Assembly argued that we should not reduce “great, mighty, and awesome” from its transcendental Torah attribute to “great, mighty, and awesome” in the political-legal sense. (Excerpts from English translation, 21–23)

He really does start out the same here! The Anshei Kenesset Hagedolah respond to the destruction of Jewish sovereignty by creating a new idea of ‘heroism” which focuses on Torah and cultural creativity instead of on power and politics. But the he adds a weird wrinkle: the rabbinic project spans both the historical moment when Jews lost sovereignty and the moment when they regained some version of political life, even if it wasn’t fully sovereign—the return to Zion under the leadership of Ezra and Nehemiah.

Whereas his previous interpretation sees the Jewish community as opposed to politics, this interpretation sees it as going beyond politics. It’s not that Jews aren’t politics—we are, and in fact, must be. It’s that Jews go beyond the political and the Jewish community cannot be reduced to a mere political community. But the idea is clearly to be both this transcendent religious community and to realize that in the concrete forms of a polity. As the derashah says: “We must have a state, as well as a legal-political nation with all its accoutrements, for the state and the nation will serve as the laboratory in which the great ideals and values of the political nation and values of “great, mighty, and awesome” will be realized.”

Community or Nation?

Part of the careful work of chapter on nationalism surrounds the significance of the term “Kenesset Yisrael”—when does he just mean “the Jews” and when does he have more robust metaphysics in mind. This is true of all of his discussions of Jewish collective life. Sometimes, such as in Kol Dodi Dofek, he is explicit about seeing the Jews as a collection of individuals. Elsewhere, as in “Jewish Sovereignty and the Redemption of the Shekhinah,” he is much more intensely nationalist.

Distinguishing these sorts of texts and conceptual threads requires being clear about the differences between the different models, and his interpretation of our Aggadah presents a good example: Is the Jewish community an anti-political community, or is it a more-than-political nation? Part of the modern idea of nationalism is exactly its political implications—the idea of national self-determination and the enshrinement of a nation within its own state. So while Rav Soloveitchik the communitarian needs the Jews to have cultural independence even if they are politically enveloped within a non-Jewish state, Rav Soloveitchik the nationalist sees the ultimate ideal of the Jewish people as not merely culturally but also politically independent—which is to say, sovereign.

]]>Rav Moshe and Amalek

Throughout Rav Moshe’s writings, he seems to define Amalek in terms of two different but related qualities: 1. Personal wickedness. 2. Denial of miracles—the relationship between them being that personal wickedness could motivate a person to deny otherwise evident miracles. In one rather unique text, however, he sees Amalek as denying miracles—but sees the way in which they do this as in some sense more fundamental.

In 1939, Rav Moshe gave a Shabbat Zakhor derashah marking 150 years since the establishment of the US constitutional regime in 1789 (published in Derash Moshe, 415–416). The derashah is in some ways a paean to US liberalism (more on this in another post) but the US is here framed in opposition to Amalek—and its twentieth century analogue, the totalitarianism of Russia and Germany (“Russland” and “Ashkenaz” in Rav Moshe’s Hebrew). R. Elli Fischer wrote a good article on this for the Lehrhaus nearly a decade ago, focusing on the American part of the derashah. Here I want to focus on Amalek.

“Every False Faith”

In this derashah, he does indeed say that Amalek “wanted to show that Israel’s success was not miraculous at all, and that therefore there was nothing to fear from them.” However, what matters more is not only that they believe that, but indeed that they “wanted to show” that this was true—that they wanted to spread this belief—and that they wanted to do so violently: “they should have begun by arguing their case with words and proving the correctness of their claim, or acknowledging defeat if unable to do so. They did not do so, but instead attacked immediately. In doing so, they revealed that the true core [of their ideology] was the sediment.” Here the denial of miracles turns out to be merely a mask (of which Amalek itself may not even be aware) for its true concern, violence. The naturalistic ideology merely serves the purpose of power and force.

In this, Amalek is exceptional, but not entirely unique:

“Every false faith in the world, and every empty ideology in the world, claims to illuminate the world and presents attractive visions meant to captivate the eye and entrap the soul. But because many people do not willingly follow these ideologies, their adherents turn to coercion, forcing everyone they can to accept their creed and ideology at sword- and spear-point.”

Belief systems, Rav Moshe says, all make promises as a way of attracting adherents. Many—perhaps even most—of these promises will ultimately prove false. Trying to maintain their level of followers, to say nothing of trying to grow, therefore leads them to resort to violence. However, this is a built-in problem which any social order other than the Torah (which is not “false”) will have to deal with. Hence, “no kingdom has the right to adopt any one creed or ideology [as its official belief system]. For in the end, only raw power will remain, not the ideology, and the result will be destruction in the world, as we see with our very own eyes” (reminder: he wrote this in 1939).

Amalek foregrounds this exactly by foregrounding violence. Instead of trying to gain adherents through persuasion and argument—through participating in “the marketplace of ideas”—Amalek started with violence. Amalek is explicitly and intentionally illiberal—it aims as ending pluralism and dialogue through violence. While all such faiths hope to ultimately emerge as the sole victors of open dialogue, Amalek shifts this focus on being the sole victor into a plan of action rather than a hope, and therefore shifts its means from free discourse to violence.

Conclusion

The derashah stages an opposition between Russia-Germany-Amalek, on the one hand, and US liberalism on the other. The US is characterized, he says, by a constitutionally-enshrined neutrality toward all creeds and ideologies. It is committed to protecting the bodily safety and security of its citizens and ensuring order, but beyond that makes no claims about the good and the right. Hence, it need enact no violence to attempt to coerce beliefs. This pluralistic framework is exactly what will lead Rav Moshe to refer to the US as a “malkhut shel hesed”—a kingdom of kindness—and as following God’s will. The opposition between Amalek and America is therefore between the illiberal combination of political power and belief, on the one hand, and the liberal insistence on keeping them separate, on the other.

The only exception to this binary opposition is the Torah. Rav Moshe admits that the Torah clearly envisions the Torah as being enforced by a king. Now is not the place to get into how he envisions that working, but I would note three things: 1. He says that this king will be “a righteous king.” 2. He says that the Jews give the Torah over to the king to enforce, suggesting both an inherent differentiation between politics and the Torah, and the consent of the Jews in their integration. 3. Most importantly, he explicitly sees this as an exception! This is not how normal politics works. The Torah, of all belief system and social orders, does not have the normal “impurities” of violence that corrupt all others. Any non-Torah political order—even a Jewish one—which attempts to forward a vision of the good life would inevitably suffer the corruptive force of violence and coercion.

]]>The essay, titled “Prayer in a World of Doubt,” deals with the topic known in Hasidut as “foreign thoughts” (mahshavot zarot)—intrusive thoughts which may come to a person during prayer, and the proper way to respond to them. This discourse is extensive and varied, with different descriptions of the thoughts and the proepr response appearing in the teachings of different Hasidic thinkers.

Rav Shagar interprets the foreign thoughts as heretical thoughts—specifically, the idea that perhaps prayer does not work. The question he confronts is: What should you do if—in the moment when you are praying—the thought comes unbidden to your mind that prayer does not work?

His answer, similar to that given by some Hasidic thinkers, is not to embrace the foreign thoughts or to reject them, but to simply accept them as part of who you are in that moment, existing alongside your prayer. Not only can you hold this contradiction, says Rav Shagar, but this is in fact a critical element of faith. See the quote below.

“In many places, “foreign thoughts” have been explained as “idolatrous thoughts,” and thus they can be presented also as doubts about faith that arise in the mind of the praying person as he prays, when suddenly the question arises within him as whether there is even anyone listening to his prayer. “Foreign thoughts” could refer to thoughts of lustful sin, but these thoughts typically derive from questions as to the existence of a creator who hears a person’s prayer. Passionate commitment (mesirut nefesh) in prayer, described in this teaching as a sacrifice and as death, means being willing to accept the doubt that arises in a person while he prayers, knowing not to respond to this doubt, but also not to suppress it and push it out of his mind in order to return to the flow of the prayer, but rather to live it out. Only then can a wondrous process take place: when a person’s doubts about faith are present alongside his prayer, it becomes a paradoxical source of elevation enabling him to reach the deepest, highest form of faith. It is the praying person’s willingness to give up on certainty, his willingness to leave his faith where it is, that brings faith to its lofty and proper place.

Our faith often derives from a desire to feel secure in our world, to grab hold of an uncertain world. Meanwhile, Rebbe Nahman proposes a faith that is not characterized by security and complete certainty. This faith leaves doubt where it is, and because it is willing to leave room for faith, it is the highest level of faith. The moment a person is willing to passionately commit and pray from within that space, without the gain which comes from certain faith, a surprising process takes place: a deep faith emerges which can springboard the praying person to another level of closeness to God. The end goal of knowing is not knowing, and thus the very readiness to commit without absolute security in the presence of a prayer who attends to prayer—this expresses faith in the infinite. This is not prayer which derives from certainty in a specific image of God who answers to the requests of his supplicants, rather it is an address to the infinite with its many possible faces. Let me emphasize that Rebbe Nahman’s words (as I interpret them) do not intend to portray prayer as a search for a personal covenant between a person and his creator in the midst of heresy—as in Rav Kook’s harmonistic approach—but on the contrary, the idea of passionate commitment in prayer (mesirut nefesh) is to know how to sustain heresy within faith, as per Rebbe Nahman’s understanding of the “empty space.” Faith is a leap. A person must continue the work of faith-based prayer even from a space of doubt.”

]]>

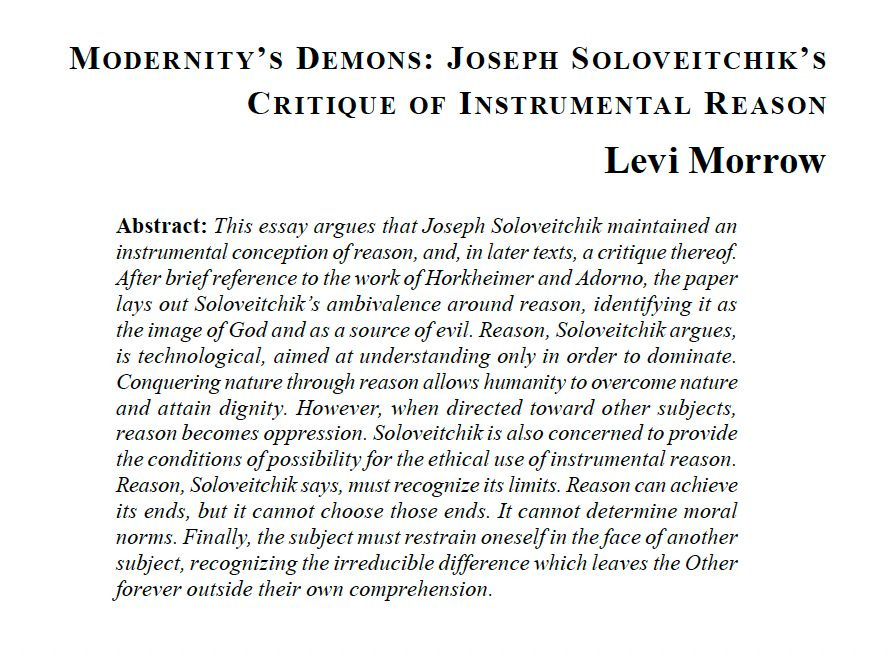

In short, the article claims that Rav Soloveitchik’s view of reason—of rational thinking—is quite ambivalent. While he grants reason a place of pride in religious life and identifies it with the image of God in “The Lonely Man of Faith,” he also sees it as distinctly limited. It can neither generate nor grasp values. This is fine, as long as it stays in its lane. If it does not recognize its limits, however, it can become “demonic.” This, he says, is the foundational sin of both humanity, in general, and western modernity, in specific. This is how he understands the rise of totalitarianism in the 21st century. Given this framing, much of his emphasis on humility and “submission” carries a distinct political weight. “Catharsis” is not just a religious experience, it is also the condition for the ethical use of reason (particularly in a pluralistic society).

The article has its roots in my early years of teaching Rav Soloveitchik at Yeshivat Orayta, as well as in Zach Truboff’s gift of his spare copy of “The Dialectic of Enlightenment.” Since writing the first draft in 2022, I’ve started working on my dissertation on Rav Soloveitchik’s political theology, and the themes of this article have continued to be central to the project. While the critique itself appears as just a single subchapter, the distinction between instrumental reason, on the one hand, and values, on the other, has only become more crucial throughout.

Link for people with institutional access. Anyone else should feel free do DM me.

]]>Against Skeptical Nomadism

A significant portion of “Sacred and Profane” is dedicated to a discussion of settlers and nomads. It is tempting to simply read this in terms of the similar dichotomy Rav Soloveitchik lays out in “Majesty and Humility” and The Emergence of Ethical Man, denoting different elements of human nature—the cosmic, universal, wandering and the local, particular, settled elements of what it means to be human. These likely are related, but the section from “Sacred and Profane” has something important to add to the discussion.

In “Sacred and Profane,” the settler is the person who “settles in” to their values. They have what Rav Soloveitchik calls “place consciousness,” but “place” here is understood metaphorically. “Place” refers to specificity and particularism—to being in this one place instead of anywhere or everywhere else. The “settler” attaches themselves to a specific set of values and is committed to them, much as a literal settler attaches to a piece of land. Echoing Rav Soloveitchik lifelong focus, the settler is the one who is willing to sacrifice for their values, rather than subordinating them to expediency and utilitarian calculations.

The nomad, in contrast, is the cultural skeptic who refuses to attach themselves to anything which might bind them. Expounding on the mysterious “ish itti” figure from the Yom Kippur sacrificial service, Rav Soloveitchik says: “He is a ‘spiritual nomad.’ He has neither culture, religion, nor a philosophical outlook of his own” (73). In their rational-critical freedom, nomads essentially divorce themselves from human values and any particular worldview—seeking only momentary utility.

The connection between nomads and skepticism owes more to Kant than to Windelband, but before explaining that, it is worth noting that it is a part of Kant that Windelband really emphasizes. In an essay simply titled, “Immanuel Kant,” he talks at length about Kant’s rejection of skepticism. This is a theme that matters quite a bit for Windelband, both because he sees the point of philosophy as the determination of values and a worldview, and also because he simply thinks relativism is bad, ridiculous, and ought to be rejected.

In terms of Kant, the exploration of nomads and settlers in “Sacred and Profane” is just expanding on an image taken wholesale from the beginning of Kant’s Preface to the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason. Discussing Metaphysics’ role as “queen of the sciences,” Kant remarks,

At first, her government, under the administration of the dogmatists, was an absolute despotism. But, as the legislative continued to show traces of the ancient barbaric rule, her empire gradually broke up, and intestine wars introduced the reign of anarchy; while the sceptics, like nomadic tribes, who hate a permanent habitation and settled mode of living, attacked from time to time those who had organized themselves into civil communities. But their number was, very happily, small; and thus they could not entirely put a stop to the exertions of those who persisted in raising new edifices, although on no settled or uniform plan. (Taken from 1900 translation by J. M. D. Meiklejohn, available online)

Here Kant says that skeptics refuse the work of trying to create metaphysical pictures of the world the way nomads refuse the work of creating settled societies. This work, he says, has mostly gone on haphazardly, or as the despotic dominion of dogma. Skepticism may have done the work of clearing away despotic dogmatism, but in refusing to construct an alternative, it creates philosophical anarchy, rather than order or civilization. The work of philosophy, then, is to encourage and improve the construction of metaphysics, so that it can be done in an orderly, systematic manner and actually accomplish its ends. For Windelband, as for Rav Soloveitchik, this is the work of reflection that enables the creation of a worldview and values.

Notably, Rav Soloveitchik’s presentation reduces the three terms of Kant’s metaphor (despotism-nomadism-settlement) to just two (nomadism-settlement). Kant’s opposition between skepticism and dogma, with constructive metaphysic as the ideal—though it has to be done well—which is opposed to both of them becomes an opposition between skepticism and affirming any worldview at all.

We could just chalk this up to Rav Soloveitchik being in some sense an apologist for traditional Judaism. He would be the first to admit that he isn’t trying to arrive at truth in a vacuum, from first principles—he thinks traditional Judaism is correct, and he is more concerned with determining what it means than with trying to demonstrate its veracity. But I think the context of Windelband and Neo-Kantian values philosophy, invoked by Rav Soloveitchik in the very midst his expounding the settler-nomad dichotomy, is important. Windelband himself locates philosophy both in opposition to skepticism, and not in opposition to dogma. While he wouldn’t celebrate dogma per se, the role he gives philosophy is one of critical reflection on certain areas of human life and activity, deriving values from them and using them to create a philosophical worldview. While still a critical endeavor, it takes certain things as givens in a way that is not easily integrated with Kant’s analogy—but which fits well the version in “Sacred and Profane.”

The Attack on History and Psychology

Another key point of intersection with Windelband and Baden Neo-Kantianism is Rav Soloveitchik’s opposition to historicism and psychologism—to any attempt to explain values (among other things) by reference to historical events or elements of human psychology.

In “Sacred and Profane,” he is less full-throatedly antagonistic to these moves, but it still comes through, both in his opposition between “eternity” and historical time—his insistence on the possibility of free action not derivable from historical forces—and his derision of psychological explanations of teshuvah. In regard to history, Rav Soloveitchik asserts that the Jewish experience of time requires belief in the “Ketz”—literally “the End.” But instead of this referring to the end of history—as if history would simply continue until it reached its natural end—it refers to the possibility of an irruption into and interruption of history. Thus both the possibility of personal change and of historical revolution (one of his examples of belief in the Ketz is Rabbi Akiva’s support for the Bar Kokhva rebellion) depend on this extra-historical possibility. This isn’t quite where Windelband ends up on the topic of freedom and historical necessity, but there is a shared discomfort with the reductively historical.

In terms of psychology, Windelband was fighting against the idea that what humans could, in practice, do with their minds was a source of truth regarding logic and philosophy. Rav Soloveitchik will elsewhere fight against the idea that elements of human psychology could be a factor in making changes to halakhah. In “Sacred and Profane, the stakes are not legal but theological and existential, and Rav Soloveitchik is more ambivalent, making room for psychological explanation, but only as a lower level to repentance. There is a form of teshuvah, he says, which “is not supernatural but psychological.” It results from normal mental dynamics and achieves a form of inner “purification. However, he says, there is a higher form of teshuvah which can have a cathartic, transformational effect on the human personality. This, he says, “is not a psychological phenomenon but a theological one, transcendent and nonrational” (76).

As noted, in “Sacred and Profane,” he is more ambivalent than oppositional. Probably the best example of when he is oppositional toward these ideas is his famous “Surrendering to the Almighty” lecture, where he says:

“One must not try to rationalize from without, the chukei haTorah and must not judge the chukim u’mishpatim in terms of a secular system of values. Such an attempt – be it historicism, be it psychologism, be it utilitarianism – undermines the very foundations of Torah umasora, and leads eventually to the most tragic consequences of assimilationism and nihilism, no matter how good the intentions are of the person who suggests it…

To speak about Halacha as a fossil, Rachmana litzlan, is ridiculous. Because we know, those who study Halacha know, it is a living, dynamic discipline which was given to man in order to redeem him and to save him. We are opposed to shinuyim (changes), of course, but chiddush is certainly the very essence of Halacha. There are no shinuyim in Halacha, but there are great chiddushim. But chiddushim are within the system, not from the outside! You cannot psychologize Halacha, historicize Halacha, or rationalize Halacha, because this is something foreign, something extraneous.

As a matter of fact, not only Halacha. Can you psychologize mathematics? I will ask you a question about mathematics; let us take Euclidean geometry. I can give many psychological explanations of why Euclid said that two parallels do not cross, or the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. If I were a psychologist, I could interpret it in psychological terms. Would it change the postulate, the mathematical postulate? And Marah d’alma Kula – Almighty God – when it comes to Torah, which is from HaKadosh Baruch Hu, all the instruments of psychology, history, and utilitarian morality are being used in order to undermine the very authority of the Halacha.” (see the transcription and links here: https://arikahn.blogspot.com/2013/03/rabbi-soloveitchik-talmud-torah-and.html)

Here psychology and historicism are put alongside utilitarianism, and all three are said to lead to nihilism. Relativism—what Rav Soloveitchik essentially has in mind with “nihilism”—was a long-time concern for Windelband, and Windelband ties in utilitarianism as well in an essay on the importance of tradition in education. It would be hard to underestimate the importance of critiquing utilitarianism for Rav Soloveitchik, so I wouldn’t reduce it to Windelbandian influence, as it were. Rav Soloveitchik’s more instrumental understanding of reason means that he can say “rationalize Halacha” and mean “make Halakhah utilitarian,” which Windelband would never abide. Nevertheless, the constellation of themes in this lecture seems significant.

None of what I have said in these two posts should be taken to reduce Rav Soloveitchik to Baden’s influence, or for that matter, to reduce the importance of other philosophical schools in his theology. Hopefully this has helped to clarify and illuminate the materials with which he was working and the context in which he understood himself to operating.

]]>The thread in question is the central importance of “values” (sometimes called “axiology”) in Rav Soloveitchik’s theology. At this point, my sense is that it would be hard to overstate their importance (but this is always the way with interesting research questions). At one point he says quite directly: “humans are axiological creatures” (Besod Hayehid Ve’hayahad, 261). I can’t lay out the full story here, which requires getting into the phenomenology of Max Scheler, but I laid out some main points in a recent post here:

Which brings us to now, to this post. After reading the first draft of my chapter on the Mesorah Community, my advisor mentioned that one thinker who might be relevant to the issue of values is Wilhelm Windelband, the founder of Baden Neo-Kantianism—parallel to Hermann Cohen, the founder of Marburg Neo-Kantianism. Rav Soloveitchik’s engagement with Cohen is pretty well known, and Mark Smilowitz wrote a dissertation just a few years ago on Rav Soloveitchik’s engagement not just with Cohen but also Natorp and Marburg Neo-Kantianism more broadly. Nothing seems to have been written on his engagement with Windelband, however.

On the one hand, perhaps this isn’t surprising. Rav Soloveitchik cites or mentions Windelband all of 4 times in his writings: once in his dissertation, twice in The Halakhic Mind, and once in “Sacred and Profane: Kodesh and Hol in World Perspectives.” However, as I have begun to read/read about Windelband’s philosophy, I have been increasingly struck by the amount of overlap with Rav Soloveitchik’s thought. Here’s I just want to highlight how Windelband and his school of Neo-Kantianism underly “Sacred and Profane,” in a manner which is explicit in the text but the extent of which is easy to miss.

“Sacred and Profane” in its Own Context

“Sacred and Profane” was originally a yartzheit lecture Rav Soloveitchik gave in memory of his father. It was then published in English in 1945 in a YU student publication, HaZedek II:2–3 (May-June 1945), republished in Gesher 3, No. 1 (June 1966), and then in Jewish Thought 3, No. 1 (Fall-Winter 1993). It was also published in Hebrew in the 90’s as well, first in Hatzofeh in Elul/September 1993, and then in the Hebrew collection Ha’adam Ve’olamo, which I have written about here:

The reference to Windelband in the essay is fairly brief. In a section defining a “Weltanschauung” or “worldview,” he says that “The modern theory of value, since Lotze, Windelband, and Rickert, the fathers of modem axiology, declares truth to be not a correlative to some ontological entity but a value that reigns supreme. If one says, ‘my culture,’ it implies not only the culture of ‘my acquaintance’” (62; page numbers are to the Jewish Thought edition). These two sentences are little more than philosophical name dropping, repeating the ideas of the preceding lines while informing the audience of their philosophical provenance and historical context. They add so little that the Hebrew translator or editor felt comfortable simply removing them entirely.

But context is important. Rav Soloveitchik wanted to tell his audience that “Sacred and Profane” was drawing on the Baden school, and once we know that, we can see how Baden concerns mark the whole text, and we can better understand what the essay is trying to do.

Weltanschauungen and “World Perspectives”

Windelband inaugurated his particular brand of Neo-Kantianism in a search both for what Kant really meant and for the continuing relevance of philosophy in the 19th century. As part of that, he argued that philosophy has a key role to play in the formation and refining of a Weltanschauung, or “worldview” (this is simplifying a much more complicated story but is essentially correct).

“Worldview” is a word which appears in “Sacred and Profane” (62), but the more frequently used term is the one that appears in the title: “world perspective.” It is very clearly being used as a translation of “Weltanschauung”: “A world perspective is not a cognitive approach to the world; it is not merely a matter of knowledge. One may be acquainted with any culture although the object of one’s knowledge need not be identical with one’s personal outlook. Cognition does not make for a Weltanschauung” (61).

So the title of essay does not reflect Rav Soloveitchik’s desire to compare the Jewish and non-Jewish understandings of the sacred and the profane—what the title might intuitively suggest, and something Rav Soloveitchik immediately does in the initial section of the essay. What the essay is fundamentally about is creating a Jewish Weltanschauung, in the same or a similar way that the Baden school talked about creating a philosophical Weltanschauung.

Values as the Core of Philosophy and Worldviews

Here is where values come in. Windelband interpreted Kant’s critical method to mean that philosophy’s job is to create norms and rules for each of the three key areas of human life: reason, will, and feeling, reflected in the areas of thinking, ethics, and aesthetics. Philosophy’s job is to reflect on these areas of human life and derive their core values, which could then be used to judge and critique these areas. In doing so, philosophy creates a worldview addressing all areas of human life. Hopefully, this would lead to a process in which, over time, the values would be realized more and more perfectly in practice. Philosophy’s capacity for reflectivity and critique make it uniquely suited for this project.

In “Sacred and Profane,” Rav Soloveitchik is reflecting on the values of the sacred and the profane as embodied in halakhah and Jewish texts (like the Rabbi Akiva pieces toward the end). Through reflecting on these and determining the core concepts of sacrality and profanity at their core, Rav Soloveitchik can create normative values representing a key part of the Jewish worldview.

This is what he is doing in the section on holiness and religion as troubling the individual rather than comforting them—parallel to Halakhic Man’s famous footnote 4—and in the section on the risk of holy ideas becoming corrupted.

This also plays a role in Rav Soloveitchik’s work more broadly. The final line of The Halakhic Mind is “Out of the sources of Halakhah, a new world view awaits formulation” (HMi, 102). This is the project of creating a halakhic philosophy that he is concerned with throughout Halakhic Mind, toward the beginning of The Emergence of Ethical Man, in early versions of what would become The Lonely Man of Faith, and elsewhere. This is the topic of Mark Smilowitz’s dissertation on Rav Soloveitchik’s “reconstructive” method and his attempt to create a halakhic philosophy in this manner. Smilowitz primarily works off Marburg Neo-Kantianism—the focus of Rav Soloveitchik’s dissertation—but given what he says in “Sacred and Profane,” it seems likely that Baden is in the mix as well.

This post has gone long, so I’m going to make the two final points of comparison into a second post discussing how “Sacred and Profane” borrows an analogy straight from Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and how it captures Rav Soloveitchik and Windelband’s discomfort with historicism, psychologism, and utilitarianism.

]]>In addition to my normal amount of busyness I am getting ready for some travel, so in lieu of a proper blog post, here is a translation of a passage from Rav Shagar’s Shiurim Al Likkutei Moharan, vol. 2 (the translation has been sitting in my Google Drive for years). The passage captures much of Rav Shagar’s religious sensibility, particularly in everything having to do with accepting our limitations and giving up on unreasonable expectations like certainty.

]]>On the one hand, a person is obligated to come close to God, and people naturally experience feelings of faith. On the other hand, these feelings must come from the way a person remains in a constant state of wonder and not-knowing in relation to the creator’s greatness, understanding that everything he knows about the infinite is nullity and nonsense. Thus a person cannot live with an awareness of being God-fearing, of knowing the meaning of life or knowing God’s existence. Absolute faith approaches a state of absolute not-knowing. Otherwise, if a person understands what cannot be understood, the divine concept will be rendered human. This lack of understanding is what gives the well-defined world of faith and religiosity its strength, its infinite dimension. I must always know that the attempt to define is never-ending, because we are dealing with something that can never truly be expressed. On the one hand, my actions carry real significance from the perspective of my faith, while on the other hand, they are meaningless in relation to the infinite. The tension between these poles—as if it’s possible to hold something in your hand, when really you can’t hold onto anything—is what Rebbe Nahman depicts as the wings that elevate a person. This experience can ‘elevate’ a person up to the spiritual world, because on the one hand he lives his life based on his own finite understanding, while on the other he knows that this understanding is meaningless in relation to the infinite. The ability to laugh at the world, thus expressing its limits in light of the divine infinitude, while simultaneously knowing that finite revelation is the expression and means through which the divine manifests—really experiencing the tension between finite and infinite—is exactly what elevates a person.

This depiction of the tension between revelation and concealment in context of closeness to God does away with our typical religious categories. Religious people often think that they have ‘an in’ with God and divine providence. This can be seen both in their prayers and in their religious mindset more generally. Their whole body language conveys a sense of self-confidence, as if God belongs to them, as if God is in their pocket. This illusory confidence expresses a false religiosity because true religious faith—as Rebbe Nahman describes it—creates a dialectic situation which demands humility. The more realistic a person’s faith is, the more a person draws close to God. But then, out of the force of his experience of the divine, he feels more distant. The more that a person recognizes the divine reality, he feels that ultimately he knows nothing at all. To flip it around, when a person seems distant from God, this actually brings him closer to infinitude, which is in essence an incomprehensible concealment.

Readiness to experience this dialectic journey of distance and closeness requires strong inner spiritual strength and courage. People naturally seek to acquire and own things, both physical and spiritual—like a label granting a person peace and quiet; “I am religious” or “I know” and therefore my life can go on as normal. In this teaching, Rebbe Nahman suggests that the more you know, the less you know, an idea that is very hard to accept from an internal perspective. This is a dialectical state. You relate to something while simultaneous negating it. To put it succinctly: when a person attains lofty faith, the distinction between faith and heresy blurs somewhat. Lofty faith when you reach the deep understanding that you don’t know anything. You must nullify yourself before the divine infinitude. This is a true religious posture before God. This faith gives up on certainty because it understands that the idea that we can “hold onto” something in the religious realm is an illusion. The believer can but stand before the divine nothingness and feel both intense, wondrous closeness as well as his distance from the infinite, his lack of understanding and his inability to know or define. From this perspective, at the deepest level, there is a place where faith and heresy connect: our inability to know the infinite. The level of lofty faith is a positive not-knowing. It opens the possibility of grasping (without the tools of reason) that which cannot be understood.

(Rav Shagar, Shiurim Al Likkutei Moharan, vol. 2, 260–262)