The trigger for my ongoing project on Rav Moshe is a letter he sent on October 3rd, 1984, in advance of the US Presidential Election wherein Ronald Reagan was elected for a second term, urging the Orthodox community to vote. The letter is interesting on its own terms, but the frequency with which it is raised makes it an ongoing concern for anyone concerned with US orthodoxy. Below, I lay out Rav Moshe’s political theology of US liberalism, which he mentions in the letter but which he develops more robustly elsewhere in his writings. Elsewhere, and possibly in another post here, I will lay out the problems that emerge when you try to read the letter through any sort of theory of democratic politics.

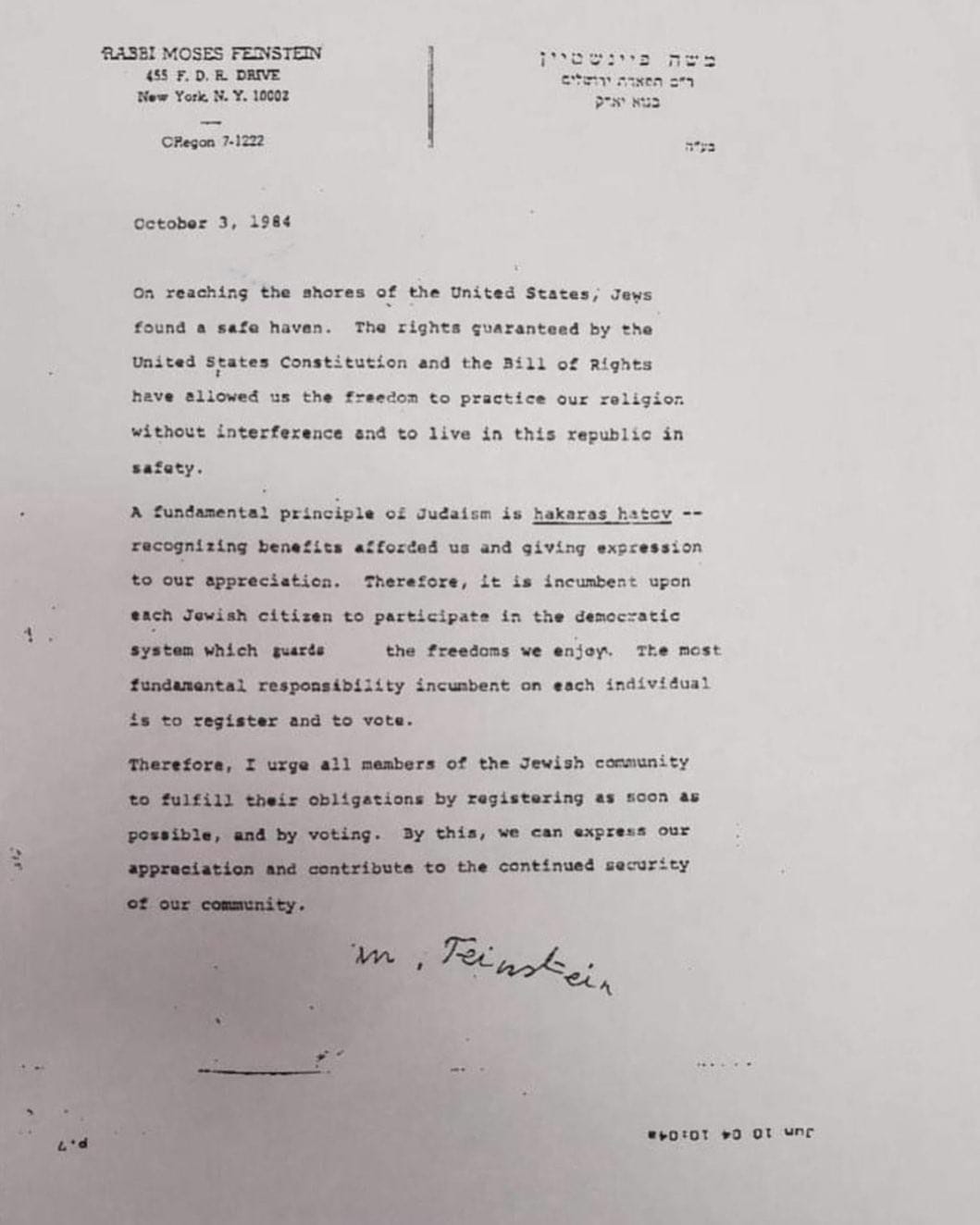

First, the letter itself. Here is an image of the letter:

And here is a digitized version of the body of the letter:

On reaching the shores of the United States, Jews found a safe haven. The rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights have allowed us the freedom to practice our religion without interference and to live in this republic in safety.

A fundamental principle of Judaism is hakaras hatov — recognizing benefits afforded us and giving expression to our appreciation. Therefore, it is incumbent upon each Jewish citizen to participate in the democratic system which guards the freedoms we enjoy. The most fundamental responsibility incumbent on each individual is to register and to vote.

Therefore, I urge all members of the Jewish community to fulfill their obligations by registering as soon as possible, and by voting. By this, we can express our appreciation and contribute to the continued security of our community.

Against Instrumental, Parochial Reasons for Voting

The key reason this letter is invoked is because it provides a non-instrumental reason to vote—something more principled that “make sure you get yours!” (or rather, “make sure we get ours”). The last line does carry a more instrumental melody—“and contribute to the continued security of our community”—but this is shockingly absent throughout the rest of the letter. This is particularly true when contrasted with other Orthodox authorities attempts to encourage voting, which fall entirely within the instrumental range. See, for example, the letters collected here by the Agudah. The only other one to mention a non-instrumental reason for voting is the one from the moetset of the Agudah in 2008, in which it feels like an afterthought after the primary, instrumental reason, and where it is clearly downstream from Rav Moshe’s letter.

In contrast, Rav Moshe gives instrumental reason a clearly secondary status. His primary reason is “hakaras hatov”—gratitude—which is underlined in the original text of the letter. His letter expounds upon the spiritual and material flourishing of the Jews in the US and how that flourishing is directly tied to the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Sure, voting can help the Jewish community secure its own interests, but more importantly: it is how the Jewish community can properly show its gratitude to the country for making it possible to lead safe, secure lives in line with the dictates of Orthodox halakhah.

Thank God for US Liberalism

It is worth noting how he very clearly and specifically envisions the US as a liberal state (liberal in the political-philosophy sense, not the partisan sense). This is a broader theme in Rav Moshe’s writings. In a derashah he gave for the Shabbat Zakhor of 1939, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the US Constitution, he said that America had “enshrined in its law that it does not maintain any particular faith or ideology, and that each person can do as they will” (Darash Moshe, vol. 1, 416). This is in contrast with the totalitarian governments of Germany and Russia, and with Amalek—whom he characterizes in the derashah as specifically illiberal, attempting to enforce ideological conformity through violence (see my previous post on this aspect of the derashah). Figured as a sort of Anti-Amalek, the US makes flourishing Jewish life possible by creating space for any and all non-violent ideologies and systems of belief.

This is a key feature of the US for him, and he mentions it regularly. In a letter about non-Jewish prayer from 1963, he remarks that “the Lord’s Prayer” said in US schools is not problematic for Jews, in part because “the rulers of our country are men of kindness (anshei ḥesed), and they do not want to impose their religion upon the other citizens—therefore they established the text that they did” (Igrot Moshe OH 1:25). The unique ḥesed of the US is tied to how it enables the Jews to flourish as Jews without imposing on them some other religion or restricting their Jewish observance. Intervening in then-ongoing debates about prayer in schools, with most Jewish organizations opposing the practice, Rav Moshe says that it is fine because the US government is fundamentally multi-cultural.

Similarly, the one letter where Rav Moshe does use the phrase “malkhut shel ḥesed” (lit., “kingdom of kindness”) to refer to the US (Igrot Moshe HM 2:29) is about how the US grants funding to all educational institutions in the country—including Jewish schools teaching their students Torah! The Jews are beneficiaries of this liberal environment—not to mention the welfare state—where instead of compelling education for a specific belief system, or even just only supporting that one belief system, the US government actually supports education for all kinds of different belief systems. Because it maintains what political philosophers call “liberal neutrality,” the US creates a welcoming environment in which Jewish life can flourish and perpetuate itself.

Notably, Rav Moshe does not see this as merely a happy accident. In the speech for the anniversary of the constitution, he says that in creating a liberal society, “they are acting in accordance with the will of the Holy One, blessed be He.” US liberalism is itself a fulfillment of the will of God (!). Moreover, the Jews’ arrival on American shores was an act of divine providence, as he says in his letter about state funding: “The Holy One, blessed be He, in His abundant mercy upon the remnant that survived from among the Jews of all the lands of Europe… brought us here.” God brought the Jews to a liberal state with significant welfare programs which encourage the flourishing of all religions in a pluralistic manner. This theological affirmation of US liberalism is the background for Rav Moshe’s articulation in his letter on voting that life in the US is something for which Jews should express gratitude.

Before expanding on the relationship of voting and gratitude, I should note that Rav Moshe is not simplistically rosy-eyed about the liberal environment in the US. In a 1979 responsum about how doctors should behave on shabbat and whether or not they should violate shabbat in order to save a non-Jew, he suggests that US liberalism actually heightens the pragmatic necessity of doing so (Igrot Moshe OH 4:79):

Given the situation in our countries today, hostility (eivah) poses a serious danger—even in countries where Jews are generally allowed to live according to the laws of the Torah—since in any case it is unacceptable that, on that basis, one should refuse to save a life.

The liberal environment of the US is a double-edged sword. The permissiveness of US government when it comes to ideological and religious multiculturalism does not extend to risk to life. In fact, Rav Moshe sees the purpose of states as protecting life (in a minimal sense; see the constitution derashah), so allowing religious beliefs to take precedence over saving a life would contradict their very purpose.

Moreover, the liberal environment also means that freedom of the press is a fact with which Jews must contend. In the continuation of the letter, he argues that the combination of free press with advanced information and communication technologies mean that eivah is always a concern, because actions by Jews in any one place could lead to antagonism against Jews anywhere else.

But in our time one must, it seems to me, be concerned about danger in every place; and also because of the dissemination of information through newspapers, immediately whatever is done anywhere in the world, there exists the stumbling block of learning from place to place, and also incitement to increase hatred to the point of murder is great through this. Therefore it is clear that in our time this must be judged as an actual danger, and it is permitted when such a case arises.

The expectation of liberal multiculturalism is reflected in the government, but ultimately permeates all of society. Living in the US therefore constitutes a historical gift to the Jews, but also brings with it its own strictures and standards. On balance, however, this is not really so different from the past—in some ways, this is Rav Moshe’s point in the responsum. There was always a concern for hostility from non-Jews on this point, and in a liberal society, that still exists, even if some of the dynamics are different. Despite that, life in the US still clearly represents a historical step forward for Jews, and for that they should be grateful.

Gratitude for Liberalism

This brings us to the issue of the relationship between gratitude and authority. Rav Moshe’s basic argument in his 1984 letter is that the gracious use of power for a person’s sake engenders a responsibility to show gratitude.

In context of Rav Moshe’s letter, it is very clear that the gracious use of power in question is the creation, maintenance, and enforcement of US liberalism. The US creates a liberal, pluralistic space in which Jewish communities can flourish, in ways we can call both positive and negative. In a “negative” sense, the US avoids establishing any one religion as the religion of the land. Even if it is in some sense a Christian country (there’s a Christian majority, it was founded by Christians, etc.), the US’s governing institutions refrain from treating Christianity as if it were the law of the land. In this way, it enables non-Christian—and even Catholic—communities to flourish.

In a “positive” sense, it grants funding to Jewish educational institutions alongside all other educational institutions. It is committed to equal access to education and providing the funding for such education, including in some ways to religious education. This combination of multi-cultural liberalism and the welfare state yields a truly remarkable situation for the Jews, one for which they should rightly show gratitude.

This gratitude is gratitude to the state. The Jews should see themselves as having received something of value from the state and as therefore bearing some sort of obligation toward it, if not exactly a debt. They should discharge this obligation, Rav Moshe says, by participating in the democratic process. Voting is not an inherent good, on this model, but something that gains value by virtue of being valued by the state.

This is, to put it mildly, a somewhat strange way to think about democratic governance. I’ll address that, hopefully, in a future post.