Il n’est rien sur la terre de si humble qui ne rende à la terre un service spécial ; il n’est rien non plus de si bon qui, détourné de son légitime usage, ne devienne rebelle à son origine et ne tombe dans l’abus. La vertu même devient vice, étant mal appliquée, et le vice est parfois ennobli par l’action. Shakespeare (Père Laurence, Roméo et Juliette, II, 3)

Il n’est rien sur la terre de si humble qui ne rende à la terre un service spécial ; il n’est rien non plus de si bon qui, détourné de son légitime usage, ne devienne rebelle à son origine et ne tombe dans l’abus. La vertu même devient vice, étant mal appliquée, et le vice est parfois ennobli par l’action. Shakespeare (Père Laurence, Roméo et Juliette, II, 3)

La différence entre la vertu et le vice est bien moins radicale que nous ne voulons le croire. Parfois, la bonté la plus efficace… est exercée par ceux qui se sont déjà compromis avec le mal, ceux qui sont membres de l’organisation même qui a lancé la balle vers l’abîme. D’où une contradiction étrange et frustrante : la bonté absolue est souvent étonnamment inefficace, tandis que la bonté compromise, éclatée et ambiguë, celle qui est touchée et souillée par le mal, est la seule qui puisse fixer des limites au meurtre de masse. Et si le mal absolu se définit en effet par son unidimensionnalité constante, cette sorte de méchanceté plus banale, la plus répandue, contient aussi en elle-même des graines de bonté qui peuvent être stimulées et encouragées par l’exemple des quelques habitants de ces régions inférieures qui ont pu en venir à reconnaître leur propre potentiel moral. Omer Bartov (2001)

Le mot « terrorisme » est chargé, et les gens l’utilisent pour désigner un groupe qu’ils désapprouvent moralement. Ce n’est tout simplement pas le rôle de la BBC de dire aux gens qui soutenir et qui condamner – qui sont les bons et qui sont les méchants. John Simpson (BBC, Octobre 2023)

La BBC est un diffuseur indépendant sur le plan éditorial dont le rôle est d’expliquer précisément ce qui se passe « sur le terrain » afin que notre public puisse se faire sa propre opinion. BBC(2023)

Les politiciens britanniques savent parfaitement pourquoi la BBC évite le mot « terroriste », et au fil des ans, beaucoup d’entre eux ont convenu en privé de cette position. Appeler quelqu’un terroriste signifie prendre parti et cesser de traiter la situation avec l’impartialité due. Le rôle de la BBC est de présenter les faits à son public et de le laisser décider ce qu’il en pense, honnêtement et sans diatribes. C’est pourquoi, en Grande-Bretagne et dans le monde entier, près d’un demi-milliard de personnes nous regardent, nous écoutent et nous lisent. Il y a toujours quelqu’un qui voudrait que nous nous emportions. Désolé, ce n’est pas ce que nous faisons. John Simpson (2023)

Alors pourquoi BBC News a-t-elle appelé les auteurs du 11 septembre des « terroristes » ? La différence cette fois-ci est-elle que la majorité des victimes sont juives, John ? Honest reporting(2023)

Le bilan de BBC Arabic en matière d’omission sur le ciblage des civils israéliens.

Aujourd’hui marque la Journée internationale du souvenir de l’Holocauste, un jour pour se souvenir des 6 millions de personnes assassinées par le régime nazi il y a plus de 80 ans. BBC (2025)

Les enfants ont été mis sur le Kindertransport. Helen Mirren(BBC, décembre 2025)

Ce programme fait l’objet d’une clarification. Le Kindertransport était l’évacuation organisée d’environ 10 000 enfants, dont la majorité étaient juifs, d’Allemagne, d’Autriche et de Tchécoslovaquie. BBC (Janvier 2026)

Six millions de personnes ont été tuées dans les camps de concentration pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, ainsi que des millions d’autres parce qu’elles étaient polonaises, handicapées, gays ou appartenaient à un autre groupe ethnique. Ranvir Singh (ITV, 2025)

Aux informations d’hier, quand nous avons rapporté les événements commémoratifs à Auschwitz, nous avons dit que six millions de personnes ont été tuées dans l’Holocauste mais nous avons crucialement omis de dire qu’elles étaient juives. C’était notre erreur, pour laquelle nous nous excusons. Ranvir Singh (ITV, 2025)

Mais combien d’hommes composent cette fameuse et controversée police de Donald Trump ? Léa Salamé (France 2, 26.01.2026)

Merci, George Floyd, d’avoir sacrifié votre vie pour la justice. Nancy Pelosi (présidente de la Chambre des Représentants, 2020)

People of Minneapolis build barricades, trapping ICE Gestapo at the scene of their latest murder in broad daylight. Not far from where they killed Renee Good a couple weeks ago, not far from where George Floyd was killed in 2020. Calla Walsh (Communist brown shirt, 2026)

The skirmish that led to Saturday’s fatal shooting of an agitator by Border Patrol agents in Minneapolis and the response that followed were driven by a complex network of far-left organizations with a wide range of causes, a Fox News Digital investigation found. A coordinated web of encrypted chats, street alerts and tracking of ICE “Abductors” in a sophisticated database reviewed by Fox News Digital shows that agitators were already mobilized at the scene where 37-year-old Alex Pretti was killed minutes before any shots were fired. ICE and Border Patrol agents were there to arrest an illegal immigrant criminal, and Pretti and others were there, outside a donut shop, to meet them as part of a strategic pattern of organized interference with law enforcement operations. Over the following hours, a national network of socialist, communist and Marxist-Leninist cells in the United States leveraged the tragic fatality into a nationwide protest operation. While grief and outrage over Pretti’s death is genuine, the network’s real-time rapid response, using short sensational video clips and emojis as weapons of propaganda, offers a window into the disciplined logistics, messaging and coordination of far-left warriors fomenting insurgency-like confrontation with authorities. “This level of engineered chaos is unique to Minneapolis. It is the direct consequence of far left agitators, working with local authorities,” Vice President JD Vance observed in a Sunday post on X.A complex network of far-left organizations was mobilized at the scene where 37-year-old Alex Pretti was killed. The encrypted Signal messages obtained by Fox News Digital in real time show that anti-ICE “rapid responders” were actively tracking, broadcasting and summoning “backup” around federal agents outside Glam Doll Donuts on Nicollet Avenue, where the shooting happened. Local “rapid responders” made at least 26 entries into a database called “MN ICE Plates” in the critical hours before and after the killing, documenting the license plate numbers and details of alleged ICE vehicles they claimed to see around Nicollet Avenue. (…) Media outlets, including CNN and MSNOW, described “angry protesters” but failed to identify the ideological networks behind the mobilization, even as protesters flashed their signs with their logos and names, touting socialism, communism and Marxism, on camera. The Minneapolis activation marked the beginning of an almost instantaneous weekend surge by far-left organizations, including hardened socialist and communist groups operating in an ecosystem that national security experts describe as an insurgent-style operation designed to exploit tragedy to wage a domestic political war. The strategy mirrors past mobilizations, including the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing in May 2020, and exploits well-intentioned public sympathy by rapidly framing Pretti — an intensive care unit nurse at a Veterans Administration hospital — as a symbol of resistance, much like Renee Good, the first victim of an ICE shooting in Minneapolis. Just as they responded in real-time to mobilize “comrades” to march on the streets within 12 hours of the U.S. arrest of Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro in early January, socialist, communist and Marxist-Leninist groups now frame their activation as an action within the “belly of the beast” against the “hyperimperialism” of the United States. Based on a digital analysis of scores of rapid-response messages following the killing on Saturday, a hub of communist and socialist nonprofit organizations emerged as key organizers of the protests. Many of them are funded by American-born billionaire Neville Roy Singham, a self-declared Marxist-Leninist living in Shanghai. Some are also offshoots of the People’s Forum Inc., a nonprofit hub Singham has funded in New York City since 2017 as an “incubator” for socialist and communist groups. (…) By early evening, the narrative had coalesced into a chorus of voices within the far-left propaganda apparatus, adopting charged historical language to brand federal officials as Nazi-like figures. At 4:12 p.m. ET, Calla Walsh, a controversial communist activist filmed this past summer in Iran shouting, “Death to America! Death to Israel!” shared a 32-second video showing barricades built with Republic Services dumpsters. She wrote, “People of Minneapolis build barricades, trapping ICE Gestapo at the scene of their latest murder in broad daylight. Not far from where they killed Renee Good a couple weeks ago, not far from where George Floyd was killed in 2020.”By evening, CNN was reporting from the 4 p.m. protest in New York City but did not identify the ideological affiliations of the organizers, even as activists openly carried signs from the Party for Socialism and Liberation, with the group’s full name printed across the bottom. Another CNN segment from Minneapolis interviewed Chris Gray, describing him only as Pretti’s “next-door neighbor.” Gray spoke about Pretti while delivering a well-scripted appeal for a general strike to dismantle the “Trump regime” and promote “non-violent resistance.” The segment did not disclose that Gray is a member of Socialist Alternative, the U.S. affiliate of the International Socialist Alternative, a “global fighting organization of workers, young people, and all those oppressed by capitalism and imperialism,” seeking to create a “socialist world.”Soon after, however, Socialist Alternative shared the interview proudly on Instagram, noting, “Chris Gray, Socialist Alternative member and next-door neighbor of Alex Pretti, speaks out.”By evening’s end, at 9:44 p.m. ET, Gloria La Riva, a co-founder of the Party for Socialism and Liberation who has described herself as “a communist,” posted a message on X, using the inflammatory language now normalized: “Alex Pretti was murdered in cold blood, everyone knows that. 10 shots in his back. All of Trump’s, Noem’s, Bovino’s lies cannot cover it up. The people’s struggle will only grow!”The Party for Socialism and Liberation used Alex Pretti’s image for its anti-ICE efforts. Party for Socialism and Liberation/X The maroon Dodge Durango in the early Signal alerts from Saturday morning is Entry No. 2069 in the publicly shared database, “MN ICE PLATES.” It included a gallery of photos of alleged ICE vehicles. At last count on Sunday, the database had 4,626 records of license plate numbers organized as “Highly Suspected ICE,” “Confirmed ICE,” “Suspected ICE,” “Cleared – Not ICE” and “Unknown.”The total number of “Confirmed ICE” entries is 2,933 records. The total number of records labeled “Abductors” is 455. A fine-print disclaimer states that the data is “for informational purposes only” and that its organizers “do not condone its use to forcibly assault, resist, oppose, impede or interfere with the official duties of any officer or employee of the United States, or of any agency in any branch of the United States Government, while engaged in or on account of the performance of official duties.”One guide, “Best Practices Guide for Neighborhood or Area Patrol / Monitors: 612,” includes a key to emojis and the jobs they represent for rapid responders. NY Post

Over the past week, Donald Trump has been talking himself into becoming an enemy of Ukraine. It seems he needs to feel this way in order for him to do what he wants to do, which is impose terms of surrender on a sovereign nation that committed the crime—in his eyes now—of refusing to allow Russia to take it over. (…) What madness, what cravenness, what repulsive factitiousness, is this? (…) Trump is under no obligation to support Ukraine. If he doesn’t, he doesn’t. But doing so while accusing Ukraine of being the aggressor in the most unjustified, pitiless, and brutal war of aggression in our time is an act of infamy almost without parallel. John Podhoretz (2025)

Even by President Donald Trump’s standards, this one was a whopper. He often plays fast and loose with the truth when trolling opponents or engaging in wild exaggerations to distract the press. But his claim that Ukraine started the current war with Russia was not a garden-variety Trump gambit. Unlike most of Trump’s jibes that send his critics into hysteria, this one was a self-inflicted wound. It was both egregiously wrong on the facts of the conflict and undermined a key U.S. policy initiative. Whatever might have led to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022—and however hard Trump loyalists want to spin his statement—there’s no doubt that it was Moscow that attacked Kyiv and not the other way around. (…) He wrongly said they had started the war by not making concessions to the Russians before it began and accused Zelenskyy of being a dictator. He said not a word of criticism about Putin, whose brutal and illegal actions are, without question, the reason for the war. Jonathan S. Tobin

The spectacle of Trump and other administration officials bullying little Denmark has gone over badly abroad. And for Trump’s domestic critics, who are already acting as if his enforcement of immigration laws marks the end of democracy, if not Western civilization itself, outrage about his Greenland policy is just one more reason for them to view him with disgust. It may be difficult to look beyond the bad optics of picking on the Danes or the question of whether a dispute about Greenland is worth risking the possible destruction of the NATO alliance. But it turns out that Trump’s concerns about the strategic importance of the massive ice-covered island are not frivolous. Nor is it outrageous for him to think that leaving it in the hands of the Danes while the United States is obliged to pay for its defense, as well as the rest of the West, is unfair. (…) In other words, they expect the United States to do in Greenland what it has essentially done for the rest of Europe since 1945: pay for its security and meekly accept that the beneficiaries of its largesse get to complain about Americans pushing them around. Much of the coverage of the controversy centers on some of the less than flattering aspects of Trump’s bluster about a country that is more ice than green, such as the report that he sent a text to Norway’s prime minister, saying since he had been denied the Nobel Peace Prize (which is awarded by the Oslo-based Nobel Committee and not the Norwegian government), he doesn’t feel obligated to play nice with Europe. But when placed in the context of the West’s necessity to invest heavily in security in Greenland and the long record of prosperous NATO countries letting the American taxpayers pay the bill for their defense, Trump’s demand seems less unreasonable. (…) the NATO nations have been relative freeloaders for many decades, sitting back and letting Americans pay for their defense, and even stationing troops and bases in Europe to ensure that it remains free. Rich Western European countries like Denmark have enjoyed the umbrella of U.S. security since World War II and have only occasionally reciprocated the assistance by actions that show they are ready to share the burden. While, thanks to Trump’s advocacy on the issue, many NATO allies are now paying for more of their defense, the current situation remains one in which America is still largely subsidizing European defense, despite heightened regional concerns because of Russian aggression against Ukraine. (…) Prior American governments have sought to purchase it, going back to the postwar Truman administration and even to the 1860s (when Secretary of State William Seward vainly sought to buy it, but then settled for getting Russia to sell Alaska). So, depicting the request as just vintage Trumpian insanity is misleading, even if the manner in which the president has pursued it is hard to defend. On the flip side, if he wasn’t blustering and making threats about Greenland, would the Europeans even listen to his arguments? Jonathan S. Tobin

Yes, he has been loud about the subject. And yes, he was loud at the Davos World Economic Forum. Yes, he had demanded “purchase” of the island and suggested the use of military force. Yes, he threatened to raise tariffs on European countries. Yes, he even suggested that—based on European opposition—he would not necessarily make his decisions on the notion of a “common defense,” i.e., NATO. That’s how he approaches problems. I wrote in 2025: “The entire second Trump administration has proven, thus far, to be an advertisement for yoga. President Donald Trump throws out a bombshell idea—annexing Canada, invading Panama, emptying Gaza, tariffs on imported air, firing a billion federal workers … and everyone gets hives.” Or annexing Greenland. The Europeans declared that they would defend the island from Trump. Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands sent small contingents of troops to take part in military exercises there. How odd that countries that couldn’t ante up the money they were obligated to spend for NATO defense against Russia suddenly found the funds and troops for Greenland. Yoga. Breathe. Downward dog. Then you find out that a lot of countries are open to trade talks; that the Abraham Accords countries have some ideas for Gaza; that the border is closed, safe and secure. And that NATO might be amenable to American requirements for Greenland. Following the U.S president’s speech in Davos, in which the threat of tariffs and military action were rescinded, and negotiations were held with Secretary General Mark Rutte of NATO, it seems the actual deal may look more like an expanded defense and resource agreement than an outright transfer of territory. The Dow surged 1.2%, the S&P 500 gained 1.16%, and the Nasdaq 1.18%. Denmark retains sovereignty and the United States gets sovereign space for military bases, plus mineral rights. The kicker? The NATO statement said: “Negotiations between Denmark, Greenland and the United States will go forward aimed at ensuring that Russia and China never gain a foothold, economically or militarily, in Greenland.” Yoga. Breathe. Cobra. Shoshana Bryen

The Trump Administration recognized the threat that we faced from the Chinese Communist Party and that it had been waging the world’s most successful political warfare campaign against the United States by making so many of the American elite partners with the Chinese Communist Party. And the Trump Administration was the first administration after, obviously, post-cold war administrations, from Clinton through Bush to Obama to Trump, that tried to turn the rudder over, recognizing the nature of the threat, that it was the regime that was the threat. It was the Chinese Communist Party that is the threat to the United States because of its ideology… So, we both suffer the consequences of that odious regime, and the Trump Administration recognized that and took measures starting to turn the rudder over. Bradley Thayer and John N. Friend r (2018)

We’re looking at a new era, in which not only the post-1990s framework is up for grabs, but even, in some ways, the post-1945 framework is being contested. (…) one problem is that the adversaries of this old system are now stronger than before and working together more cohesively. China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela (…) The second problem, I think, is that on our side, we have not paid sufficient attention to the relationship between public opinion and power. (…) back in the early 1990s (…) now that the Soviet Union has gone, we can do more. The opponent of freedom has disappeared from the stage, so we can raise our objectives. We can now start worrying about gender justice in Senegal and honest voting in Kazakhstan. (…) And as the fear faded, the Jacksonians, a very large and important element in American policy, stopped being interested in foreign policy, stopped wanting to pay for foreign policy, stopped wanting to take risks in the name of foreign policy. In 1992, the first real post-Cold War election, you had two candidates: George H. W. Bush, architect of victory of the Cold War, winner of the Gulf War, a reunifier of Germany; and Bill Clinton, the governor of Arkansas, who didn’t know that much about foreign policy per se, but thought that America should be spending more time worrying about American problems. He wanted less foreign policy, and he beat Bush. Eight years later, you have Al Gore, the great statesman, the vice president who’s been everywhere, the climate champion, the really smart guy, who knows the world leaders and knows the world. And then you have George W. Bush, another governor who thinks we’ve got too much foreign policy—we don’t need to be doing this nation building abroad, America needs to focus on America first. 2008: John McCain, the great Republican statesman, the architect of reconciliation between the US and Vietnam, the man famous globally for his foreign policy credentials. And then this guy who’s a first-term senator from Illinois, who thinks that really, America needs to focus more on stuff at home, and that all of this grandiose war on terror, foreign policy stuff is getting us into a bad place. 2016: Secretary of State and ex-First Lady Hillary Clinton, great world expert. (…) Versus Donald Trump, a real estate developer from Queens, who thinks we’ve got too much of this darn foreign policy thing and need to be America first. So at every opportunity from the end of the Cold War, American voters voted for less foreign policy. But one way or another, each of these presidents managed to end up giving them more. (..) So the American foreign policy system, in a sense, has been running on fumes for quite a while. And Donald Trump’s embrace of much less foreign policy, the heck with all this multilateralism, reached a lot of people at a visceral level. Although, as I noted in last week’s column, he’s talking about regime change in Venezuela, humanitarian interventions in Nigeria, and nation building in Gaza. So we seem to be back. And this might suggest an avenue for a challenger, for a candidate in 2028. (…) The final reason that I would draw your attention to that things are not going well with this system is that I think we got confused over the nature of power—and the relationship of soft power and other kinds of power. You could argue that the last thirty years (…) many liberals have fallen victim to two different varieties of what I would think of as liberal fundamentalism. The one we’re most familiar with is what people call market fundamentalism. If we just have free trade, then the whole world is going to be fine. And the answer to any economic problem is to deregulate market forces. That’s not all wrong, and there’s a lot of truth in it. But like everything else, it needs to be adjusted from the blackboard to the actual world. (…) The other one is what I would call rights fundamentalism, that if we double down on human rights everywhere, everything is going to be great. (…) But when you convert these from goals that you are pursuing in a complicated world, sometimes in rather strange, crooked ways, to “I’m going to get there no matter what, I’m going to bulldoze everything,” and you have a kind of monomaniacal approach, you get in trouble. I would say we also, even as we embrace these kinds of fundamentalisms, we also forgot the role of hard power in establishing those world systems. We did not win the Second World War because everybody thought Eleanor Roosevelt’s ideas about a universal declaration of human rights were just so compelling that that was how the world wanted to live. We won World War II because we killed millions of people in amazing orgies of destruction and blood. We assembled violence and force. One night in Tokyo, we killed 84,000 Japanese civilians in deliberate terror attacks on civilian neighborhoods, in a country where homes were built of paper. I’m not even getting to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Not even the Huns destroyed as many European historic monuments as we did in that war. Franklin Roosevelt was advised that he should not call for unconditional surrender by Germany because that would prolong the war, increase suffering. It would unite Germans around Hitler’s leadership. And Roosevelt’s conviction was that one of the reasons that we were having the Second World War was that the Germans had called for the armistice in 1918 before the war got to Germany. The war was still outside. They didn’t know what war was. And he said—this time, they will. So when we talk about the beautiful world order that emerged from the ashes of World War II, we forget not only the cruelties and the horrors of the actual war, and that we won it because we were better at organizing productive powers for destruction than our enemies were. We also forget just how for years after that war, the president of the United States basically could decide how many calories everybody in Germany and Japan would get to eat. And there was a decade of real suffering, even as their economies began to recover. So you have a whole generation of people whose worldview includes the right thing. War is terrible, and war against the United States is even worse. And fifty years later, we thought it was our moral purity and our piety that were upholding the world order. It’s still not. (…) It’s a good thing. I’m all for moral piety and purity and all those things. But again, the reason that China doesn’t attack Taiwan today is because it’s not quite sure what would happen if it did. The reason Russia hasn’t nuked anybody in Ukraine or Europe has more to do with their fears of what would happen if they did, than to any admiration of the moral example that we’re setting by not nuking anyone. So that doesn’t mean that soft power has no place. And it certainly doesn’t mean that morality in international life has no place. But we’ve missed it. We’ve tried to do too much. We have failed to understand the sources of strength. We have allowed ourselves to turn elements of our ideology into idols, so that we have become liberal fundamentalists rather than liberals. And these things have gotten us into trouble. Well, where can we go from here? (…) I would suggest that what the United States got kind of lured into after the end of the Cold War was we became what you might call an “offshore hegemon.” That is, we were doing things that an offshore balancer does by trying to prevent any country from dominating Europe, any country from dominating Asia, any country from being able to interrupt the flow of oil from the Middle East, those classic, hard-power things. But we tried to then set up a political order in our own image in each of these theaters. So we promote democracy, and so on and so forth, all of which is fine, no principled objection. But we didn’t have the power. We didn’t have the push. I think we need to go back to being more of an offshore balancer, where we’re not going to try to tell every country in the Middle East how to live. We’re not going to try to tell every country in Southeast Asia what their policy on elections should be. I mean, our civil society can and will continue to do this, but we focus our attention much more on some of the classic and really very limited goals that Anglo-American diplomacy has sought. I think we would also, in economic terms, need to take much more seriously the degree to which the Chinese abuse of the world trading system and the inept construction of the world trading system that created something that was so vulnerable to abuse. The problem with this is not simply that China has a balance of trade surplus with the United States. (…) But that in a sense, China monopolized the beneficial consequences of industrialization and growth, so that there hasn’t been industrialization, say, in Egypt comparable to what we’ve seen in China. (…) In a sense, this great tree grew up, and nothing could grow in the shade. Many of the economic and social problems that Africa, parts of Asia, and certainly the Middle East have, have some connection to this. A global trading system in which, say, the Europeans could have said, it’s really important to us that to the extent that our economic market is going to help promote development and stability, we do it across the Mediterranean, where that really has a big impact on us, and that we might have been a little bit more attentive to trying to make our own neighborhood a bit more prosperous, and so on. So I think we would move away from the idea of a global, one-size-fits-all approach to a lot of these policy things and a theory-driven approach. Free trade is good. This looks like free trade, therefore this is good—I wouldn’t disagree that free trade is good (…) But like everything else, you have to do it in a practical, pragmatic way, with a careful thought for the political, economic, social, and geographical and geopolitical consequences of what you do. But I’d say, America, we’re stuck with a global foreign policy. The fact that Trump was adjudicating disputes between Cambodia and Thailand and Azerbaijan and Armenia, that the isolationist restrainer America-first president gets drawn into these things should remind us that in a sense, no matter what somebody wants, this is where you end up going a lot of times as an American. So you need to try to go there intelligently and try to think very hard, not just about what you can do, but about what you can avoid doing. So a more nuanced, grand strategy that does take into account historic American interests and priorities—that is less doctrinaire, more pragmatic—this is not going to be a recipe for universal joy, or you get this—most of the time, most foreign policy doesn’t work very well. It was Henry Kissinger who said that a lot of the time, your alternatives are you’re trying to avoid the catastrophic and get to the merely bad. (So again, foreign policy is not like a test. If you do the homework and study and apply the right principles, you’ll get an A. It doesn’t work like that. It’s much more like an athletic contest, where even the best athlete in the world will go out there and screw things up, commit fouls, miss easy shots, get hornswoggled by some opponent. And your success today doesn’t mean you’re going to be successful tomorrow. It’s much more of an engagement than it is an academic exercise. Walter Russell Mead (2025)

The pivotal moment came when Trump briefly imposed 145% tariffs on China in April. These soaring duties were designed to halt trade, force reshoring, and counter Beijing’s subsidies—marking a triumph in pushing back against decades of economic predation. Congressional report (2019)

While many on both the left and the right wrongly thought [Trump’s] embrace of the slogan “America First” amounted to isolationism, they clearly misunderstood what he meant by it. Far from withdrawing from the world, Trump is determined to defend American interests abroad, though correctly understands that structures created for that purpose in the late 1940s are obsolete. What Trump is doing amounts to a return to what historian Niall Ferguson accurately analogized to the “gunboat diplomacy” and “big stick” foreign policy of President Theodore Roosevelt in the opening decade of the 20th century. This was made clear in the administration’s National Security Strategy published in November, which essentially was the blueprint for freedom of action to defend American interests in South America, whereby the Monroe Doctrine is being updated and strengthened into a new “Donroe Doctrine.” The assumption of the foreign-policy professionals during the last 80 years was that such behavior was just the sort of high-handed great power actions that led to disaster in 1914 and again in 1939. They thought that the high-minded ideals of world governance and collective security articulated in the U.N. Charter and the rhetoric of post-war American presidents could ensure that aggressors could be stopped and wars avoided. They point to the fact that the great powers never went to war against each other from 1945 to the fall of the Berlin Wall—and even to the present after the Soviet Union collapsed—as proof that the liberal world order was not just preferable but an absolute necessity. The creation of the United Nations, and a few years later, NATO, made sense as the planet emerged from the nightmare of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. The West then faced the need to resist the aggressive expansionism of Soviet communism. But neither the world body nor the fashioning of a Western alliance that sought to prevent Moscow from bringing other nations inside its totalitarian Iron Curtain prevented World War III from ever being fought. It was, instead, the possession of nuclear weapons by both rival global superpowers that deterred them from war, even when confrontations, like the one over the Soviets installing missiles in Cuba in 1962, took them to the brink. The new order didn’t abolish the basic truth uttered by Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz about war being “the continuation of policy by other means” or end great power politics. Nuclear weapons just made the cost of escalating direct confrontations too costly to consider. NATO served a purpose in ensuring that the Soviet aggression of the late 1940s was halted. So, too, did the U.S. resolve in Korea, when the South was invaded by the Communist North. But what the architects of the United Nations failed to realize was that the structure they created could be taken over by the very forces opposed to Western ideals. That the United Nations is today a bastion of antisemitism—and it and its agencies spend so much of their efforts and energy undermining and attacking Israel—is not an anomaly. It’s the natural outcome of a world body that is largely controlled by nations and movements that are opposed to Western ideals and values. The simple and unavoidable truth is that the only way to defend those values, American interests, as well as the existence of Israel, is to go around or supersede multilateral institutions. Their preservation cannot be allowed to depend on the ideas of a now bygone era. The United States, as Ferguson has also accurately noted, is locked in a new Cold War; only this time, against China and its allies in Moscow, Tehran and Caracas. It should learn from the past, but it won’t win this conflict solely by working with the tools, like NATO, that were invented to cope with the challenges of the last one. It’s only to be expected that the assertion of American power in South America or elsewhere, such as Iran—where Trump joined the Israeli campaign to destroy its nuclear program and which he has now also threatened should it violently suppress protests—will be opposed by ideologues who think international institutions are more important than national sovereignty. The point being is that if you don’t want rogue regimes to be allowed to export illegal drugs that kill Americans or to be used as bases by Iran or China, the only answer is for Washington to act. Waiting for a global organization to undertake operations that most of its members oppose or the assent of NATO allies is almost always going to lead, as it has on so many fronts, to inaction. Some administrations, like that of Barack Obama, turned that dependence on multilateralism into something of a fetish. The result was, among other things, the catastrophe in Syria (where Obama walked back his 2013 “red line” threats) and the 2015 Iran deal that set Tehran on a course to have nuclear weapons, with which it could dominate the Middle East and threaten the rest of the world. The argument that American unilateralism will encourage Beijing to attack Taiwan is nonsense. As Russia showed in Ukraine and Iran proved when it fomented its multifront war against Israel on the watch of a Biden administration that was similarly wedded to multilateral myths, it was U.S. weakness—not tough-minded Trumpian strength wielded unilaterally—that is likely to lead to more wars. It may well be that Trump’s every utterance and act will continue to send liberals and leftists over the edge, no matter how sound or reasonable his policies (such as his success in halting illegal immigration) may be. (…) The most important conclusion to be drawn from this latest instance of Trump’s freelancing while the global establishment clutches its pearls is that it is only by Washington’s willingness to act on its own that the threats to America, the West and the State of Israel can be effectively met. Far from the greatest peril being an erratic Trump let loose on the world stage, the president’s single-minded belief in defending American national interests is the best hope for fending off the machinations of enemies of the West. A mindless belief in the transcendent importance of the solutions that were believed necessary in 1945 to prevent another global war is not going to protect us in 2026 and the years to come. Jonathan S. Tobin

The most enduring folk tale involving Alexander is about not overthinking—the story of the Gordian knot. In the city of Gordium, a prophet had declared the future ruler of all Asia would have to solve the impossible problem of untying an incredibly complex knot in a rope. Alexander simply took his sword and cut through it. Action, not ingenuity. Simplicity, not complexity. Solve a problem not by solving it but by ending the problem itself. Doesn’t this explain better than any other theory the approach of Donald Trump in Iran and Venezuela? For decades, both enemies of America seemed to pose problems for us that seemed unsolvable, though the reasons shifted over time. Iran’s nascent nuclear problem could not be dealt with directly in the 2000s because we were too busy in Iraq. Venezuela’s seizure of American assets in 2008 relating to natural gas could not be dealt with because we had a history of standing by and accepting it when oil-rich countries nationalized their assets. When both regimes stole elections and oppressed their people while sponsoring terrorism against the United States—with bombs and narcotics, and cooperating with each other as Iranian assets went to Venezuela for passports to use to cross the border into the U.S. to move drugs and establish potential cells—we could not and did not act because, well, having not acted before, we weren’t going to act now. Faced with these problems in 2024 from both regimes, Donald Trump surely got the same advice Joe Biden and Barack Obama and George W. Bush had received from other world leaders and from the experts inside his own government. The consequences of action were simply too hard to game out. All options were bad, so the least bad option—using Aristotelian moderation as your guide—would be not to do too much. Use sanctions. Send ships to the area. Support covert forces. Even help the enemy of your enemy (Israel). But do not do more. Looking at these knots, and having been told that untangling them would be near impossible, Trump chose another route. He took out his sword—the unparalleled American military—and sliced through them. In 37 hours from beginning to end, he took out Iran’s nuclear program. And in five hours this weekend, he extricated Nicolas Maduro from his position atop the Venezuelan greasy pole. By doing so, he invokes another, more recent paradox, though I know in citing it I am going to get slammed by people for misunderstanding its original meaning. That is Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. By which I mean, the idea that these problems are irresolvable is inalterably changed by resolving them—the facts on the planet Earth have changed in the Middle East and South America because of what Trump chose to do, and the prudent calculations that governed inaction are no longer operative because they describe the options in a world that no longer exists in the same way. (…) Trump’s actions are only to be considered extreme if you view them in isolation. They came in response to efforts before them to make things happen without military involvement. (…) It stands to reason that if the regime challenging the United States is itself an extreme actor, taking radical action against it might itself be the most prudent course. Alexander didn’t need to spend years solving the Gordian Knot problem when he had a blade sharp enough to solve it for him. John Podhoretz

The present state of the world is increasingly a scene of rivalry between (A) a Western camp, dominated by the USA and Israel, and (B) an increasingly unified anti-Western one that includes notably Islamists, led until recently by Iran, with Turkey seeking to take over, along with China, Russia, and various “southern” nations in Africa and South America. (C) Europe, after long abdicating its role in international affairs to the US on the one hand and the UN-“Third world” on the other, is beginning to seek to get back in the game. The current state of Great Britain and France, if not quite Germany, shows them in the throes of political stagnation, nowhere better illustrated than by the French parliament’s recent withdrawal of its decision to advance the retirement age from 62 to 64—at a time when other European nations are setting it closer to 70. The nations in the B group, dominated by philosophies that partake of the epistemology of resentment, find in militant Islam—Islamism—its bellwether, if not its model, and in particular the guarantee for the vastly increased antisemitism of the group’s Western members, focused on the Israeli “genocide” of the Palestinians. The “Red-Green Alliance” links the Western political Left to the Islamist dream of world conquest, drawing strength (as well as cultural self-contempt) from the latter’s self-sacrificing religious fanaticism that justifies its followers’ claim to “love death” where the Judeo-Christian world—which they would reject—“loves life.” One of the strangest recent developments of this conflict has been the (re)emergence of a “right-wing” antisemitism that includes nostalgia for Nazism as well as Holocaust denial-minimization in its rejection of the mid-20th century victories of liberal democracy on the American model. A lot of this playing at épater les bourgeois, stimulated by the internet-era mania for “self-expression” that favors the scandalous over the reasonable, can be used as a discovery-mechanism to ascertain the contemporary West’s degree of self-hatred: its rejection of Christianity along with Judaism. This nihilistic fondness for Mein Kampf and outlandish Jewish conspiracy theories stands in contrast to the at least nominal striving of both the green and red revolutionary modes toward an ultimate utopia, whether socialist or Islamic. (…) As Jonathan Tobin writes for the Jewish News Service on January 6 in “Venezuela, Trump and the end of the liberal world order”, Trump’s unpredictable coup cut through the rhetoric of feckless diplomacy to reveal the obsolescence of the system of international law-and-order that had been inaugurated after WWII with the creation of the United Nations in the hope of establishing an international “community of nations.” The flawlessly-carried-out kidnapping of Nicolas Maduro and his wife with the purpose of dismantling the multi-billion dollar narco-terrorist trade that Venezuela has been providing, while hopefully initiating that nation’s liberation from a dictatorship that has driven perhaps a third of its people into exile, demands the same comparison to a post on X praising Hitler and blaming Churchill for WWII as to a “Democratic Socialist” speech condemning Trump’s act as in violation of “international law”: that between real action to solve the world’s problems and empty verbiage, whether “serious” or nihilistic. Doran has clearly been observing the social-media scene for so long that he has come to take it for the real world, when it is merely a self-mocking caricature of the realm of illusion that has emerged from the failed liberal dreams that built the UN, all too quickly transformed into the temple of world antisemitism. Call it instinct or philosemitism, Trump has understood that antisemitism is no longer a foible of a semi-confident upper class, but a figure of the West’s death wish, and that to revel in one’s own society’s destruction is not a solution but a surrender. The “endless wars” of the Bush era failed because, in the spirit that founded the United Nations, they expected that the Western formula for the good society could be applied worldwide. What Trump has been doing is rather to confidently affirm the superiority of American values on the world scene. Neither Iran nor Venezuela can be said to “deserve” their current regimes, which was not true either in Saddam’s Iraq or Afghanistan, and it is not unlikely that Trump’s nearly casualty-free acts of aggression in both countries will ultimately have positive effects, given that, unlike the neocon wars, their aims are in synchrony with the fundamental social values of these nations. John Podhoretz’ title says it all in his recent “Trump and the Gordian Knot” (…). Slicing through the fatuous rhetoric about international law that permits the most egregious dictatorships and criminal enterprises to flourish, Trump dared to apply Alexander’s masterful example to Venezuela’s international drug trade by striking at its key figure, doing what had been supposed to be the UN’s job. Whether or not the end result will be a happy return to prosperity on the Western model may be yet unclear, but what justified Trump’s action is that only by demonstrating the continued strength of this model can the West, under the leadership of the USA, retain its position of world leadership. It pays to reflect on what this tells us about the political instincts of the American population in giving Trump his solid victory in 2024. To elect Trump was clearly not to make a safe choice; in the face of the obsolescence of the postwar world order, only audacity, egocentric as it may be, can find new paths. In this sense, Trump’s MAGA slogan is anything but empty bravado. (…) like most “brainworkers,” I have never taken Trump for a political ideal, in the way I might have felt about Reagan, for example. But his bull-in-the-china-shop antics, however I might on occasion find them egregious, reflect the kind of deal-making personality that alone in these times can break through the Gordian knots in which the post-WWII world has enveloped itself. (…) And although the consequences of Trump’s Maduro coup are anything but certain, the mere fact of pulling it off makes clear that, as Podhoretz realizes, the world of international relations today is so choked with irrationality that trying to solve the problems of Maduro’s illegitimacy by “diplomatic” means—certainly not the means he used to remain in the presidency after a lost election—would be in fact a category error worthy of an Orwellian satire. Whatever else occurs, the USA, in Venezuela as in Iran, by the demonstrated skills of its military, have incontestably shown the world who is the “strong horse”—and as the Islamists know well, in an era of international tension, that is the closest we can come to certainty. So long as the US can convince its external enemies of this, it should be able to deal with the feckless partisans of the death-wish of Western civilization. Eric Gans

The present state of the world is increasingly a scene of rivalry between (A) a Western camp, dominated by the USA and Israel, and (B) an increasingly unified anti-Western one that includes notably Islamists, led until recently by Iran, with Turkey seeking to take over, along with China, Russia, and various “southern” nations in Africa and South America. (C) Europe, after long abdicating its role in international affairs to the US on the one hand and the UN-“Third world” on the other, is beginning to seek to get back in the game. The current state of Great Britain and France, if not quite Germany, shows them in the throes of political stagnation, nowhere better illustrated than by the French parliament’s recent withdrawal of its decision to advance the retirement age from 62 to 64—at a time when other European nations are setting it closer to 70.

The nations in the B group, dominated by philosophies that partake of the epistemology of resentment, find in militant Islam—Islamism—its bellwether, if not its model, and in particular the guarantee for the vastly increased antisemitism of the group’s Western members, focused on the Israeli “genocide” of the Palestinians. The “Red-Green Alliance” links the Western political Left to the Islamist dream of world conquest, drawing strength (as well as cultural self-contempt) from the latter’s self-sacrificing religious fanaticism that justifies its followers’ claim to “love death” where the Judeo-Christian world—which they would reject—“loves life.”

One of the strangest recent developments of this conflict has been the (re)emergence of a “right-wing” antisemitism that includes nostalgia for Nazism as well as Holocaust denial-minimization in its rejection of the mid-20th century victories of liberal democracy on the American model. A lot of this playing at épater les bourgeois, stimulated by the internet-era mania for “self-expression” that favors the scandalous over the reasonable, can be used as a discovery-mechanism to ascertain the contemporary West’s degree of self-hatred: its rejection of Christianity along with Judaism. This nihilistic fondness for Mein Kampf and outlandish Jewish conspiracy theories stands in contrast to the at least nominal striving of both the green and red revolutionary modes toward an ultimate utopia, whether socialist or Islamic.

As Michael Doran suggests in “Giant Abroad, Midget at Home” (Tablet Magazine, January 2026), the hidden stimulus behind this tendency might well be traced to Tucker Carlson’s tenuous roots in the traditional Protestant American ruling class at the turn of the twentieth century, whose largely “social” antisemitism reflected a nativist reaction to the influx of European immigrants that ended with the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924. Thus, knowingly or not, today’s Gen Z groypers identify along with Carson with that now-defunct ruling class’s contempt for the “plebeian” 20th century wrought by European immigration, of which the Jews can be seen as the archetype.

Yet nearly every day serves to disprove Doran’s idea that Trump, while impressing the rest of the world, has become at the same time a “midget” at home by neglecting American voters’ increasing impatience with economic conditions.

As Jonathan Tobin writes for the Jewish News Service on January 6 in “Venezuela, Trump and the end of the liberal world order”, Trump’s unpredictable coup cut through the rhetoric of feckless diplomacy to reveal the obsolescence of the system of international law-and-order that had been inaugurated after WWII with the creation of the United Nations in the hope of establishing an international “community of nations.”

The flawlessly-carried-out kidnapping of Nicolas Maduro and his wife with the purpose of dismantling the multi-billion dollar narco-terrorist trade that Venezuela has been providing, while hopefully initiating that nation’s liberation from a dictatorship that has driven perhaps a third of its people into exile, demands the same comparison to a post on X praising Hitler and blaming Churchill for WWII as to a “Democratic Socialist” speech condemning Trump’s act as in violation of “international law”: that between real action to solve the world’s problems and empty verbiage, whether “serious” or nihilistic. Doran has clearly been observing the social-media scene for so long that he has come to take it for the real world, when it is merely a self-mocking caricature of the realm of illusion that has emerged from the failed liberal dreams that built the UN, all too quickly transformed into the temple of world antisemitism.

Call it instinct or philosemitism, Trump has understood that antisemitism is no longer a foible of a semi-confident upper class, but a figure of the West’s death wish, and that to revel in one’s own society’s destruction is not a solution but a surrender. The “endless wars” of the Bush era failed because, in the spirit that founded the United Nations, they expected that the Western formula for the good society could be applied worldwide. What Trump has been doing is rather to confidently affirm the superiority of American values on the world scene. Neither Iran nor Venezuela can be said to “deserve” their current regimes, which was not true either in Saddam’s Iraq or Afghanistan, and it is not unlikely that Trump’s nearly casualty-free acts of aggression in both countries will ultimately have positive effects, given that, unlike the neocon wars, their aims are in synchrony with the fundamental social values of these nations.

John Podhoretz’ title says it all in his recent “Trump and the Gordian Knot” (Commentary, January 4, 2026). Slicing through the fatuous rhetoric about international law that permits the most egregious dictatorships and criminal enterprises to flourish, Trump dared to apply Alexander’s masterful example to Venezuela’s international drug trade by striking at its key figure, doing what had been supposed to be the UN’s job. Whether or not the end result will be a happy return to prosperity on the Western model may be yet unclear, but what justified Trump’s action is that only by demonstrating the continued strength of this model can the West, under the leadership of the USA, retain its position of world leadership.

It pays to reflect on what this tells us about the political instincts of the American population in giving Trump his solid victory in 2024. To elect Trump was clearly not to make a safe choice; in the face of the obsolescence of the postwar world order, only audacity, egocentric as it may be, can find new paths. In this sense, Trump’s MAGA slogan is anything but empty bravado. When, as Doran’s analysis malgré elle makes clear, our real choice is between Trump and the puerile insolence of the groypers, there is really no choice at all.

As readers of these Chronicles since 2016 will note, like most “brainworkers,” I have never taken Trump for a political ideal, in the way I might have felt about Reagan, for example. But his bull-in-the-china-shop antics, however I might on occasion find them egregious, reflect the kind of deal-making personality that alone in these times can break through the Gordian knots in which the post-WWII world has enveloped itself. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, as a relevant example, would have been unthinkable had Trump been president rather than Biden.

And although the consequences of Trump’s Maduro coup are anything but certain, the mere fact of pulling it off makes clear that, as Podhoretz realizes, the world of international relations today is so choked with irrationality that trying to solve the problems of Maduro’s illegitimacy by “diplomatic” means—certainly not the means he used to remain in the presidency after a lost election—would be in fact a category error worthy of an Orwellian satire.

Whatever else occurs, the USA, in Venezuela as in Iran, by the demonstrated skills of its military, have incontestably shown the world who is the “strong horse”—and as the Islamists know well, in an era of international tension, that is the closest we can come to certainty. So long as the US can convince its external enemies of this, it should be able to deal with the feckless partisans of the death-wish of Western civilization.

Aristotle was the tutor of Alexander the Great, hired in 343 BCE by Alexander’s father Philip II when the future conqueror was 13 years old. Aristotle, the greatest of all philosophers, sought to describe the world as it is and not the world as it should be, that having been the focus of his teacher Plato. Aristotle’s signature contribution to the annals of human understanding centers on the mean—how to find the proper balance between the churning passions that can drive us to reckless and self-destructive behaviors and the often panicky instinct for self-preservation that can both protect and paralyze us. It is Aristotle who teaches us the importance of prudence as a hedge against impulsivity and boldness as a hedge against inaction.

Was Alexander a good student? Often considered the most successful military man in history, felled not in battle but by natural causes at the age of 32 after 12 years as the leader of Macedon, he was a perpetual motion machine and astonishingly innovative as a tactician—and viewed through most of history as the peerless example of the rewards that can be garnered from martial glory. “None but the brave,” wrote the poet John Dryden in his glowing portrait of a banquet celebrating Alexander and his wife Thais upon Alexander’s seizure of Persia, “deserves the fair.” It seems unlikely that Alexander was a real-life model of the golden mean.

The most enduring folk tale involving Alexander is about not overthinking—the story of the Gordian knot. In the city of Gordium, a prophet had declared the future ruler of all Asia would have to solve the impossible problem of untying an incredibly complex knot in a rope. Alexander simply took his sword and cut through it. Action, not ingenuity. Simplicity, not complexity. Solve a problem not by solving it but by ending the problem itself.

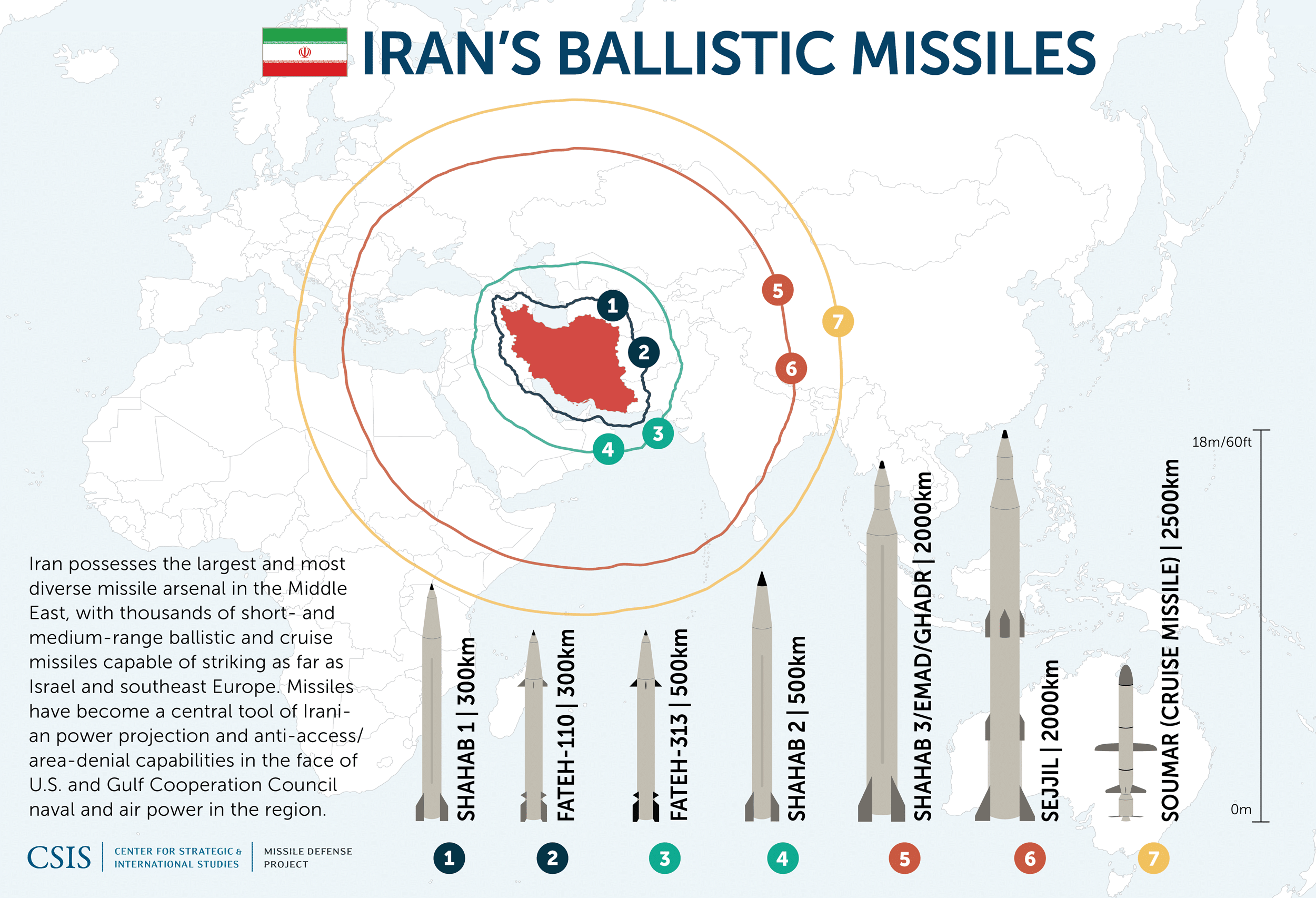

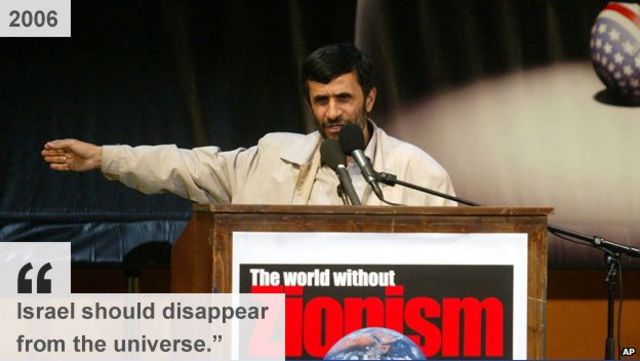

Doesn’t this explain better than any other theory the approach of Donald Trump in Iran and Venezuela? For decades, both enemies of America seemed to pose problems for us that seemed unsolvable, though the reasons shifted over time. Iran’s nascent nuclear problem could not be dealt with directly in the 2000s because we were too busy in Iraq. Venezuela’s seizure of American assets in 2008 relating to natural gas could not be dealt with because we had a history of standing by and accepting it when oil-rich countries nationalized their assets. When both regimes stole elections and oppressed their people while sponsoring terrorism against the United States—with bombs and narcotics, and cooperating with each other as Iranian assets went to Venezuela for passports to use to cross the border into the U.S. to move drugs and establish potential cells—we could not and did not act because, well, having not acted before, we weren’t going to act now.

Faced with these problems in 2024 from both regimes, Donald Trump surely got the same advice Joe Biden and Barack Obama and George W. Bush had received from other world leaders and from the experts inside his own government. The consequences of action were simply too hard to game out. All options were bad, so the least bad option—using Aristotelian moderation as your guide—would be not to do too much. Use sanctions. Send ships to the area. Support covert forces. Even help the enemy of your enemy (Israel). But do not do more.

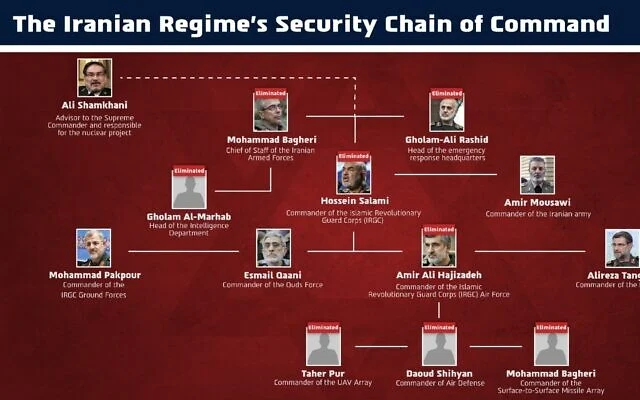

Looking at these knots, and having been told that untangling them would be near impossible, Trump chose another route. He took out his sword—the unparalleled American military—and sliced through them. In 37 hours from beginning to end, he took out Iran’s nuclear program. And in five hours this weekend, he extricated Nicolas Maduro from his position atop the Venezuelan greasy pole.

By doing so, he invokes another, more recent paradox, though I know in citing it I am going to get slammed by people for misunderstanding its original meaning. That is Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. By which I mean, the idea that these problems are irresolvable is inalterably changed by resolving them—the facts on the planet Earth have changed in the Middle East and South America because of what Trump chose to do, and the prudent calculations that governed inaction are no longer operative because they describe the options in a world that no longer exists in the same way.

These actions could have gone haywire, like the Desert One hostage-rescue fiasco in 1980. But they didn’t. And we don’t know where the Iran strike will lead, although right now, it looks like the world is safer and one of history’s most evil regimes is weakening to the point of possible collapse. And we don’t even know what Monday will look like in Caracas, not even to say what next year will look like.

Aristotle didn’t say prudence required inaction. He opposed the extremes. And Trump’s actions are only to be considered extreme if you view them in isolation. They came in response to efforts before them to make things happen without military involvement. As Marco Rubio said, we spent a year offering Maduro all kinds of generous deals. He rejected them, called Trump a coward, dared him to act. It stands to reason that if the regime challenging the United States is itself an extreme actor, taking radical action against it might itself be the most prudent course. Alexander didn’t need to spend years solving the Gordian Knot problem when he had a blade sharp enough to solve it for him.

Voir également:

As with much of the criticism of just about anything that President Donald Trump does, many, if not most, of the lamentations about the U.S. capture of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro are highly predictable.

The Marxist left immediately took to the streets in defense of the now-imprisoned leader of the narco-terrorist regime in Caracas with the same speed and determination with which they sought to support the Hamas-led Palestinian attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, or to oppose the Israeli and U.S. strikes on Iran’s nuclear program last June. The isolationist far-right, like Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) and former Rep. Marjorie Taylor-Greene (R-Ga.), denounced the president’s actions as a sign that Trump was implementing a neocon foreign policy. Antisemites on both ends of the political spectrum also echoed the reflexive claim by Maduro’s second-in-command and putative successor, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, that the American strike had “Zionist undertones.”

A debate that transcends Trump

A bitter debate about the American effort to both halt the flow of drugs from that country and to end the oppressive rule of a regime that has turned a once-prosperous and democratic nation into a failed state from which millions have fled has ensued. However, it is about more than just the usual knee-jerk opposition of the left to the president or conspiracy theories rooted in Jew-hatred.

The issue isn’t just whether Trump has started something he can’t finish or the legalities involved in the American arrest of a foreign leader, albeit a corrupt and tyrannical drug smuggler who stole elections, in his own capital. At stake is whether the administration’s unilateral actions are destroying the establishment of what is generally referred to as the “liberal world order.” That order is considered by many to have ended the anarchic great power rivalries that led to two world wars in the first half of the 20th century. The president is clearly seeking to topple a hostile government of a weaker nation for motives that may be as economic in nature as they are about stopping the flow of drugs to the United States, let alone restoring democracy in Venezuela. And that reminds some commentators of a bygone era of “imperialism” and the lack of international restraints on such actions.

But that’s a tipoff that Trump is on the right track.

It’s important to understand the context for the American effort in Venezuela as transcending the usual hand-wringing from the left or Trump-deranged establishment liberals about an out-of-control MAGA administration.

To the contrary, Trump seems to be responding to problems that the supposedly more responsible foreign-policy elites have not only failed to solve but have actually aided and abetted because of their belief in multilateralism. The complaints of the editors of The New York Times, whose editorial denounced the administration for a policy that was both “illegal and unwise,” aren’t really about the erosion of congressional checks on the use of force abroad. Nor are they about the growth of executive power, which dates back to the 1960s, or sensible reasons for concern about the ways the American effort could go wrong.

Their real argument is about a belief that the United States must always bow to the constraints enforced upon it by the United Nations or the fears of its NATO allies. That also comes from columnists like the Times’ David French, M. Gessen and Michelle Goldberg, who thinks Trump is no different from a superpower mafia don.

It is for this reason that those who believe that the current priority must be to defend the West against both the red-green alliance of Marxists and Islamists that the Maduro regime was an integral part of and the growing geostrategic threat from the Communist government of China should be cheering for Trump. And that goes double for those who rightly worry about the way that the international community and its institutions have sided with the ongoing war against Israel by those who seek its destruction.

Post-war myths

There are serious concerns about what happens next in Venezuela, or in related news about whether Trump’s talk of acquiring Greenland will lead to a messy and unnecessary confrontation with Denmark. But the laments for a situation in which both the United Nations and America’s NATO allies are powerless bystanders while Washington exerts its influence and power are misguided. The notion that the post-war order and the multilateral institutions that are part of it are indispensable to preserving peace holds enormous appeal to many around the globe who loathe or fear the United States. It also appeals to those who believe in it as an ideal apparatus for global governance. That remains the conventional wisdom embraced by the chattering classes and the foreign-policy establishment that views most of what Trump has done on the world stage with distaste, if not horror.

But they are wrong. The liberal orthodoxy that unilateralism is inherently misguided is the real problem, not Trump’s willingness to use American power, whether or not anyone else approves.

While many on both the left and the right wrongly thought his embrace of the slogan “America First” amounted to isolationism, they clearly misunderstood what he meant by it. Far from withdrawing from the world, Trump is determined to defend American interests abroad, though correctly understands that structures created for that purpose in the late 1940s are obsolete.

What Trump is doing amounts to a return to what historian Niall Ferguson accurately analogized to the “gunboat diplomacy” and “big stick” foreign policy of President Theodore Roosevelt in the opening decade of the 20th century. This was made clear in the administration’s National Security Strategy published in November, which essentially was the blueprint for freedom of action to defend American interests in South America, whereby the Monroe Doctrine is being updated and strengthened into a new “Donroe Doctrine.”

The assumption of the foreign-policy professionals during the last 80 years was that such behavior was just the sort of high-handed great power actions that led to disaster in 1914 and again in 1939. They thought that the high-minded ideals of world governance and collective security articulated in the U.N. Charter and the rhetoric of post-war American presidents could ensure that aggressors could be stopped and wars avoided.

They point to the fact that the great powers never went to war against each other from 1945 to the fall of the Berlin Wall—and even to the present after the Soviet Union collapsed—as proof that the liberal world order was not just preferable but an absolute necessity.

The creation of the United Nations, and a few years later, NATO, made sense as the planet emerged from the nightmare of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. The West then faced the need to resist the aggressive expansionism of Soviet communism. But neither the world body nor the fashioning of a Western alliance that sought to prevent Moscow from bringing other nations inside its totalitarian Iron Curtain prevented World War III from ever being fought. It was, instead, the possession of nuclear weapons by both rival global superpowers that deterred them from war, even when confrontations, like the one over the Soviets installing missiles in Cuba in 1962, took them to the brink. The new order didn’t abolish the basic truth uttered by Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz about war being “the continuation of policy by other means” or end great power politics. Nuclear weapons just made the cost of escalating direct confrontations too costly to consider.

NATO served a purpose in ensuring that the Soviet aggression of the late 1940s was halted. So, too, did the U.S. resolve in Korea, when the South was invaded by the Communist North. But what the architects of the United Nations failed to realize was that the structure they created could be taken over by the very forces opposed to Western ideals. That the United Nations is today a bastion of antisemitism—and it and its agencies spend so much of their efforts and energy undermining and attacking Israel—is not an anomaly. It’s the natural outcome of a world body that is largely controlled by nations and movements that are opposed to Western ideals and values.

Winning the Second Cold War

The simple and unavoidable truth is that the only way to defend those values, American interests, as well as the existence of Israel, is to go around or supersede multilateral institutions. Their preservation cannot be allowed to depend on the ideas of a now bygone era. The United States, as Ferguson has also accurately noted, is locked in a new Cold War; only this time, against China and its allies in Moscow, Tehran and Caracas. It should learn from the past, but it won’t win this conflict solely by working with the tools, like NATO, that were invented to cope with the challenges of the last one.

It’s only to be expected that the assertion of American power in South America or elsewhere, such as Iran—where Trump joined the Israeli campaign to destroy its nuclear program and which he has now also threatened should it violently suppress protests—will be opposed by ideologues who think international institutions are more important than national sovereignty. The point being is that if you don’t want rogue regimes to be allowed to export illegal drugs that kill Americans or to be used as bases by Iran or China, the only answer is for Washington to act. Waiting for a global organization to undertake operations that most of its members oppose or the assent of NATO allies is almost always going to lead, as it has on so many fronts, to inaction.

Some administrations, like that of Barack Obama, turned that dependence on multilateralism into something of a fetish. The result was, among other things, the catastrophe in Syria (where Obama walked back his 2013 “red line” threats) and the 2015 Iran deal that set Tehran on a course to have nuclear weapons, with which it could dominate the Middle East and threaten the rest of the world.

The argument that American unilateralism will encourage Beijing to attack Taiwan is nonsense. As Russia showed in Ukraine and Iran proved when it fomented its multifront war against Israel on the watch of a Biden administration that was similarly wedded to multilateral myths, it was U.S. weakness—not tough-minded Trumpian strength wielded unilaterally—that is likely to lead to more wars.

It may well be that Trump’s every utterance and act will continue to send liberals and leftists over the edge, no matter how sound or reasonable his policies (such as his success in halting illegal immigration) may be. It’s equally true that there are no guarantees that American intervention in Venezuela will work. Although by not committing to a full-scale invasion, Trump appears to be heeding his own criticisms of the George W. Bush administration’s blunders in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The most important conclusion to be drawn from this latest instance of Trump’s freelancing while the global establishment clutches its pearls is that it is only by Washington’s willingness to act on its own that the threats to America, the West and the State of Israel can be effectively met. Far from the greatest peril being an erratic Trump let loose on the world stage, the president’s single-minded belief in defending American national interests is the best hope for fending off the machinations of enemies of the West. A mindless belief in the transcendent importance of the solutions that were believed necessary in 1945 to prevent another global war is not going to protect us in 2026 and the years to come.

Voir de même:

Understanding the world China seeks to create by 2049, when the PRC turns 100.

If Xi’s “Dream” is realized, we can envision a world where by the mid-21st century, democratic governments survive in the West, but Beijing’s political model will have the upper hand in the international system. As with the Cold War, the struggle is material — economic and military power matter — but will also and ineluctably be ideological. Certainly, its course will pose, and its outcome answer, an ideologically dispositive question: Will egalitarianism remain the dominant ideal in international politics, or will it cede leadership back to authoritarianism? However lamentable, due to the expansion of China’s power and influence, it is likely that authoritarian politics will be the norm without serious challenge from the West. It is probable that China will advance this new wave of authoritarianism to augment its legitimacy. Touting its superiority, Beijing will also advance arguments not dissimilar from “The End of History” arguments made in the West in the early 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In contrast to the liberal democratic and free market principles of the Washington Consensus, Beijing’s political model is offering the developing world a regime-type neutral investment model based on “noninterference” in domestic affairs and the promise of “no strings attached” loans and other forms of financial assistance. This business model is part of China’s “charm offensive” and appears to be growing in popularity, as many around the world see the Chinese way of doing business as a better alternative to the structural adjustment programs of the International Monetary Fund or the push for democratic reform often associated with Western aid.

During the Cold War, the United States served as a global beacon for political elites who embraced certain values and ideas. Today, China is offering authoritarian values that are appealing to governments whose hold on power is threatened by U.S. principles such as the rule of law, free speech, democracy, and transparency and accountability in government.

By 2049, China will be ideationally self-confident and able to exert dominance more effectively in the economic, political, and military realms. Beijing will no longer integrate or negotiate but rather expect others to accept the China Order. Indeed, we are already witnessing the early stages of international politics under Chinese dominance. China’s ongoing development of military bases in the South China Sea is a clear violation of international law and its attempts to suppress free speech, particularly criticism of the CCP, outside its own borders speaks volumes to its goal of supplanting liberal values with authoritarianism.

Bradley A. Thayer is a Professor, University of Texas, San Antonio and John M. Friend is a Visiting Scholar, University of Hawai’i. They are authors of How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and the Balance of Power in International Politics (Potomac, 2018).

Voir de plus:

Below is a transcript of Mead’s talk, lightly edited for clarity. Watch the entire lecture, including audience Q&A, on our YouTube channel.

This is one of those very interesting moments in world history—not a very happy moment, but an interesting one—when the framework that Americans, with some help from some of our important allies, helped to set up after the end of World War II.

We revised it in the 1970s, when the Bretton Woods currency system collapsed, and Nixon and Kissinger reshored it and introduced a kind of trilateralism to try to boost American power from Western Europe and Japan. And after the fall of the Soviet Union, we doubled down on it. And the idea was that the kind of Western world order that had gotten us through the Cold War would be expanded in the post-Cold War era.

And that now doesn’t seem to be happening. And a lot of Americans aren’t sure that they want it to happen. So we’re looking at a new era, in which not only the post-1990s framework is up for grabs, but even, in some ways, the post-1945 framework is being contested. And the questions that I would like to look at tonight are a mix of, well, why is this happening? If we tried to conceive of where America might go, Americans might try to take this now, what should our response be? And how likely is it that we would succeed?

So let’s talk about why the old system is in trouble. One of the reasons is a no-fault reason: nothing lasts forever in world affairs. Everybody’s always talking about how we’re having an unprecedented wave of technological change. Social media is upending everything. New tech is sweeping out everything. Well, if that’s true, why should the international order not also be changed? Why should the world not be in upheaval if everybody’s lives in the world are in upheaval? So this part is not anybody’s mistake. Human history isn’t the sort of thing where you solve the problem and then live happily ever after. That’s not how things work.

So we’re in a new age. Old assumptions, old institutions, aren’t working the way they used to. We have to think about new ones. Well, again, that’s human history. And that is driving a lot of this.

Beyond that, one problem is that the adversaries of this old system are now stronger than before and working together more cohesively. China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela—you can add or subtract the ones that you like—they don’t agree on a lot of things. They disagree on what they would like to put in place of the world system that exists.

They’ve also had some failures—ask in Iran how the last couple of years have gone for them. So it isn’t all winning, winning, winning. But on the whole, China, in particular, but Russia, also, has had some success in changing the international environment around them. And they want to continue. So that’s one problem—the adversaries are back.