| CARVIEW |

The post Quantum Programming, Error Mitigation, and More appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>OpenFermion

To get started I want to give my perspective on the state of affairs in programming quantum computers. Many people ask how one programs a quantum computer and about the existence of quantum programming languages like a quantum version of C, Python, or Haskell. While work is being done in this area, the majority of algorithm development is still done in terms of quantum gates, the quantum analog of logical operations like AND, NOT, or XOR. That is, we program in a language that is often more primitive than assembly language one would use on a classical computer. In my opinion, this is because we don’t yet have a pool of algorithms large enough from which to draw the abstractions that would form a programming language. I think a more plausible model for the short term is identifying the key application where quantum computers are expected to have the largest impact, and helping users from that application use a quantum computer to solve their problems. These will likely take the form of domain specific languages (DSLs), APIs, or even just tools that provide the same interface one is used to, but designed to run calculations with a quantum back end.

We spent a long time thinking about this problem in the specific field of quantum chemistry, which studies how to simulate molecules on a computer before you make them in a lab or at a level of detail/resolution your instruments have difficulty accessing. This field has been identified as one of the front runners for early, high impact applications on a quantum computer, but it has a few challenges. For example, the amount of domain knowledge required to run a quantum chemistry calculation can be a bit daunting, requiring one to understand basic molecular structure as well as more esoteric topics like particular Gaussian basis set discretizations. To add to this difficulty, even though its quantum, the language for similar concepts in quantum computing can be entirely different, meaning a quantum chemist may have a hard time understanding how quantum algorithms operate.

These challenges make some of our goals especially challenging. Namely, we would like classical users of electronic structure to be able to use quantum computers for their application and developers of classical electronic structure to be able to contribute to new quantum algorithms. Moreover, we would like experts in quantum algorithms to be able to overcome the substantial domain knowledge barriers to make contributions to algorithms as well. In an attempt to solve these problems, we developed an open source package designed to ease this transition from all angles. We call this project OpenFermion, which is maintained on github at https://www.openfermion.org, and we wrote about our development philosophy and design in the release paper.

Since we released the initial versions of the project, we’ve been excited to have contributions, both big and small, from a large number of institutions and collaborators. I think all of the developers are excited for the ways this can involve more people in the development of algorithms for quantum chemistry on a quantum computer, and help make this dream a reality! I’m excited by the prospect that similar libraries may be released for other application areas as well!

Error Mitigation

It’s been some time since I last wrote about the quantum error mitigation (QEM) technique we introduced for quantum simulation problems that we termed the quantum subspace expansion (QSE). At present, quantum computers remain short of the requirements for full fault tolerance, and I believe one of the best hopes for performing useful computations on a quantum device before we reach full fault tolerance is error mitigation techniques, which try to remove the errors using additional measurements or other techniques. I’m particular excited about the quantum subspace expansion due to its ability to improve results without knowledge of the error model and approximate excited states as well. When we wrote the initial theory paper introducing the idea, we had some friction with the reviewers over the fact that it hadn’t yet been experimentally demonstrated. Well, I’m excited to say that it now is!

In a recent collaboration with the Siddiqi group at Berkeley, the initial predictions of error mitigation and excited state determination were experimentally confirmed on a superconducting qubit system in our paper titled Robust determination of molecular spectra on a quantum processor. I’m personally excited for the future of this technique and its potential to boost us into the realm of useful computations for quantum chemistry on a pre-fault-tolerant quantum computer.

Low depth simulation on realistic quantum devices

In the early days of quantum algorithms, the actual way the devices are wired up and connected is likely to matter in determining if we can run our algorithms. Much of the development that is done in the field of quantum algorithms works with a rather abstract model of a computer, without paying much attention to the overhead that is involved in mapping such a specification to a real quantum device. An example of this is writing quantum circuits that assume an all-to-all connectivity, when the actual device might only allow nearest neighbor connections.

I’m excited to report that recent algorithmic developments have allowed us to demonstrate how to simulate the dynamics of an electronic system in a depth that is linear in the size of the system, and moreover, this can be achieved on a quantum device that has only linear, nearest neighbor connectivity. For the quantum chemists out there, that is a real-time step forward in the full CI space, at a cost that is linear in the size of the system. This complexity is difficult to achieve classically for even a method like DFT (despite asymptotic claims). It’s developments like these that fill me with hope that quantum computers are going to change the landscape of quantum chemistry forever.

The post Quantum Programming, Error Mitigation, and More appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Spun, not stirred appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>I was wondering what I should write about first, when everyone’s favorite internet friend, targeted advertising, gave me a hand. In particular, Instagram’s algorithm determined that I was the kind of person that liked to spend a few 100 dollars on exotic new ways to make coffee, and the crazier the better. The algorithm certainly isn’t wrong, having personally dabbled with vacuum coffee makers, homemade nitrogen taps, and other unnecessarily complicated variants of coffee in the past, but I digress. It showed me an ad for the Spinn device, something that appears to be designed to make coffee via centrifuge. I think that’s a cool idea, but I reserve judgement on the general idea until I taste the final product! If it’s stupid and it works, it isn’t stupid!

What I don’t quite reserve judgement on, is everything around the coffee. While I’m not sure we’ll have another JuiceBro (aka Juicero) moment, I do wonder how many people out there actually wake up saying “if only I could talk to my coffee maker”. Featuring Amazon Alexa integration, I suppose we’ll soon find out, with the ability to ask Spinn to make you coffee, but presumably no ability for it to move the cup in place for you. Maybe it can store a few extra cups in its trashcan-chique design. Will people really opt to change the grind speed via the app or enjoy notifications from the coffee machine about what kind of coffee it prefers to have inside it? Maybe.

Internet of things (IoT) devices, like a wifi enabled coffee maker, being hijacked for bot nets or general mischief is certainly not new. However, I think wifi control of something like a home-centrifuge might be. Centrifuges are amazingly cool devices, but they aren’t entirely benign. They are high energy tools, and while I wouldn’t necessarily agree with the opening line of that article, that “centrifuge explosions occur frequently in laboratories”, they have to be operated and programmed with care. I personally prefer owning IoT devices that at least require a little creativity for people or our eventual machine overlords to plan my demise, but your mileage may vary. Here’s to hoping this new coffee maker Spinns its way into my heart, but not in the literal sense.

The post Spun, not stirred appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Basic quantum circuit simulation in Python appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>Brief background

A classical digital computer is built upon a foundation of bits, which take on values of 0 or 1, and store information. Clearly we also need to manipulate and work with that data, and the action on bits are performed by classical logical gates, such as the “AND” gate. In analogy to classical bits, in quantum computing, we have quantum bits, which take on values ![]() and

and ![]() . Similarly, we need to manipulate the data stored in quantum bits, and the equivalent operations are called quantum gates. Quantum bits have a number of nice properties absent in their classical counterparts, such as superposition and entanglement, and quantum gates are designed to make sure they can exploit these features, a property known as unitarity. For the purposes of this simple post, the exact details of these properties will be unimportant, as a correct mathematical representation of qubits and quantum gates often allows us to have these features naturally in our numerical simulations.

. Similarly, we need to manipulate the data stored in quantum bits, and the equivalent operations are called quantum gates. Quantum bits have a number of nice properties absent in their classical counterparts, such as superposition and entanglement, and quantum gates are designed to make sure they can exploit these features, a property known as unitarity. For the purposes of this simple post, the exact details of these properties will be unimportant, as a correct mathematical representation of qubits and quantum gates often allows us to have these features naturally in our numerical simulations.

One Qubit

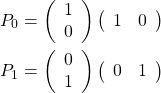

The state of a qubit may be represented as a column vector, and conventionally

(1)

In Python, we can represent such states as arrays in Numpy with the correct dimensions as:

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import scipy.linalg

Zero = np.array([[1.0],

[0.0]])

One = np.array([[0.0],

[1.0]])

which gives us a good representation of either the ![]() (Zero) or

(Zero) or ![]() (One) state. Say we wanted to create a superposition of

(One) state. Say we wanted to create a superposition of ![]() and

and ![]() , for example, the standard

, for example, the standard ![]() state which is defined by

state which is defined by ![]() . The factor

. The factor ![]() is called a normalization factor, and helps ensure the relation to a probability distribution. If we wanted to create this state, one way of doing this in Python might be to define a normalization function, and input the raw state into it as

is called a normalization factor, and helps ensure the relation to a probability distribution. If we wanted to create this state, one way of doing this in Python might be to define a normalization function, and input the raw state into it as

NormalizeState = lambda state: state / sp.linalg.norm(state) Plus = NormalizeState(Zero + One)

Now that we know how to create single qubit states, we might want to be able to perform interesting actions on them. Quantum gates in acting on single qubits are given by two-by-two matrices. One interesting gate is the Hadamard gate, given by

(2) ![]()

we can represent this gate in Python and examine its action on the state ![]() (that is,

(that is, ![]() ) through the following:

) through the following:

Hadamard = 1./np.sqrt(2) * np.array([[1, 1],

[1, -1]])

NewState = np.dot(Hadamard, Zero)

where “np.dot” in Python serves the role of matrix multiply for Numpy arrays. Take a look at NewState, you should find it has a striking resemblance to state we just examined a few lines ago…

More than one qubit

While one qubit is interesting, more than one is certainly more interesting. How do we generalize what we just learned about representing one qubit to many qubits? States of many qubits sometimes have a few different notations, for example ![]() or

or ![]() , which are the same state. The symbol

, which are the same state. The symbol ![]() is a source of confusion to many people, as rapid switches between its implicit and explicit use are rampant in quantum computing, and the symbol is essentially absent in some fields of physics, despite the operation being ubiquitous. The symbol

is a source of confusion to many people, as rapid switches between its implicit and explicit use are rampant in quantum computing, and the symbol is essentially absent in some fields of physics, despite the operation being ubiquitous. The symbol ![]() stands for the “tensor product” between two states and it allows for a correct description of many particle or many qubit states. That is, the space occupied by 2 qubits is the tensor product of the space of two single qubits, similarly the space of

stands for the “tensor product” between two states and it allows for a correct description of many particle or many qubit states. That is, the space occupied by 2 qubits is the tensor product of the space of two single qubits, similarly the space of ![]() qubits is the N-fold tensor product of

qubits is the N-fold tensor product of ![]() single qubit spaces. Time spent on the Wikipedia page for tensor product is prone to causing excessive head-scratching wondering what the “universal property” is, and how it’s relevant. Fear not, most of these abstract properties are not required reading for working with a practical example of a tensor product, which is what we will do here.

single qubit spaces. Time spent on the Wikipedia page for tensor product is prone to causing excessive head-scratching wondering what the “universal property” is, and how it’s relevant. Fear not, most of these abstract properties are not required reading for working with a practical example of a tensor product, which is what we will do here.

A practical example of a tensor product that we will use here, is the Kronecker product, which is implemented in Numpy, Matlab, and many other code packages. We will use the fact that it faithfully takes care of the important properties of the tensor product for us to represent and act on many qubit states. So how do we build a correct representation of the state ![]() or

or ![]() using it in Python? Using the Kronecker product, it’s as easy as

using it in Python? Using the Kronecker product, it’s as easy as

ZeroZero = np.kron(Zero, Zero) OneOne = np.kron(One, One) PlusPlus = np.kron(Plus, Plus)

What about an entangled Cat state such as ![]() you ask?

you ask?

CatState = NormalizeState(ZeroZero + OneOne)

And if we want to create a 5-qubit state, such as ![]() ? We can simply chain together Kronecker products. A simple helper function makes this look a bit less nasty

? We can simply chain together Kronecker products. A simple helper function makes this look a bit less nasty

def NKron(*args):

"""Calculate a Kronecker product over a variable number of inputs"""

result = np.array([[1.0]])

for op in args:

result = np.kron(result, op)

return result

FiveQubitState = NKron(One, Zero, One, Zero, One)

Take note of how the size of the state grows as you add qubits, and be careful not to take down Python by asking it to make a 100-Qubit state in this way! This should help to give you an inkling of where quantum computers derive their advantages.

So how do we act on multi-qubit states with our familiar quantum gates like the Hadamard gate? The key observation for our implementation here is the implicit use of Identity operators and the Kronecker product. Say ![]() denotes a Hadamard gate on qubit 0. How do we represent

denotes a Hadamard gate on qubit 0. How do we represent ![]() ? The answer is, it depends, specifically on how many total qubits there are in the system. For example, if I want to act

? The answer is, it depends, specifically on how many total qubits there are in the system. For example, if I want to act ![]() on

on ![]() , then implicitly I am acting

, then implicitly I am acting ![]() and if I am acting on

and if I am acting on ![]() then implicitly I am performing

then implicitly I am performing ![]() , and this is important for the numerical implementation. Lets see the action

, and this is important for the numerical implementation. Lets see the action ![]() in practice,

in practice,

Id = np.eye(2) HadamardZeroOnFive = NKron(Hadamard, Id, Id, Id, Id) NewState = np.dot(HadamardZeroOnFive, FiveQubitState)

Luckily, that’s basically all there is to single qubit gates acting on many-qubit states. All the work is in keeping track of “Id” placeholders to make sure your operators act on the same space as the qubits.

Many-qubit gates require a bit more care. In some cases, a decomposition amenable to a collection of a few qubits is available, which makes it easy to define on an arbitrary set of qubits. In other cases, it’s easier to define the operation on a fixed set of qubits, then swap the other qubits into those slots, perform the operation, and swap back. Without covering every edge case, we will use what is perhaps the most common 2-qubit gate, the CNOT gate. The action of this gate is to enact a NOT operation on a qubit, conditional on the state of another qubit. The quantum NOT operation is given by the Pauli X operator, defined by

(3) ![]()

In order to perform this action dependent on the state of another qubit, we need a sort of quantum IF-statement. We can build this from projectors of the form ![]() and

and ![]() that tell us if a qubit is in state

that tell us if a qubit is in state ![]() or

or ![]() . In our representation, the so-called “bra”

. In our representation, the so-called “bra” ![]() is just the conjugate transpose of the “ket”

is just the conjugate transpose of the “ket” ![]() , so these projectors can be written as an outer product

, so these projectors can be written as an outer product

(4)

With this, we can define a CNOT gate on qubits ![]() and

and ![]() as

as ![]() . So if we wanted to perform a CNOT operation, controlled on qubit 0, acting on qubit 3 of our 5 qubit state, we could do so in Python as

. So if we wanted to perform a CNOT operation, controlled on qubit 0, acting on qubit 3 of our 5 qubit state, we could do so in Python as

P0 = np.dot(Zero, Zero.T)

P1 = np.dot(One, One.T)

X = np.array([[0,1],

[1,0]])

CNOT03 = NKron(P0, Id, Id, Id, Id) + NKron(P1, Id, Id, X, Id)

NewState = np.dot(CNOT03, FiveQubitState)

This covers almost all the requirements for simulating the action of quantum circuit of your choosing, assuming you have the computational power to do so! So long as you can reduce the circuit you are interested in into an appropriate set of 1- and 2-qubit gates. Doing this in the generic case is still a bit of a research topic, but many algorithms can already be found in this form, so it should be reasonably easy to find a few to play with!

Measurement

Now that we’ve talked about how to simulate the action of a circuit on a set of qubits, it’s important to think about how to actually get information out! This is the topic of measurement of qubits! At a basic level, we will want to be able to ask if a particular qubit is 0 or 1, and simulate the resulting state of the system after receiving the information on that measurement! Since qubits can be in superpositions between 0 and 1 (remember the state ![]() ), when we ask that qubit for its value, we get 0 or 1 with some probability. The probability of qubit

), when we ask that qubit for its value, we get 0 or 1 with some probability. The probability of qubit ![]() being in a state

being in a state ![]() is given by the fraction of the state matching that, which can be concisely expressed as

is given by the fraction of the state matching that, which can be concisely expressed as

(5) ![]()

where ![]() is some generic state of qubits and

is some generic state of qubits and ![]() is the same projector we had above, acting on the

is the same projector we had above, acting on the ![]() ‘th qubit. If we measure a 0, then the resulting state of the system is given by

‘th qubit. If we measure a 0, then the resulting state of the system is given by

(6) ![]()

recalling that anywhere where the number of qubits don’t match up, we are following the generic rule of inserting identity operators to make sure everything works out! In Python, we could simulate measurements on a Cat state using the above rules as follows

import numpy.random

CatState = NormalizeState(ZeroZero + OneOne)

RhoCatState = np.dot(CatState, CatState.T)

#Find probability of measuring 0 on qubit 0

Prob0 = np.trace(np.dot(NKron(P0, Id), RhoCatState))

#Simulate measurement of qubit 0

if (np.random.rand() < Prob0):

#Measured 0 on Qubit 0

Result = 0

ResultState = NormalizeState(np.dot(NKron(P0, Id), CatState))

else:

#Measured 1 on Qubit 1

Result = 1

ResultState = NormalizeState(np.dot(NKron(P1, Id), CatState))

print "Qubit 0 Measurement Result: {}".format(Result)

print "Post-Measurement State:"

print ResultState

If you look you will see that upon measurement the state collapses to either the state ![]() or

or ![]() with equal probability, meaning that a subsequent measurement of the second qubit will yield a deterministic result! This is a signature of entanglement between the two qubits!

with equal probability, meaning that a subsequent measurement of the second qubit will yield a deterministic result! This is a signature of entanglement between the two qubits!

Summary

So in this short post we’ve covered how to represent qubits, quantum gates and their actions, and measurement of qubits in Python by using a few simple features in Numpy/Scipy. These simple actions are the foundation for numerical simulation of quantum circuits and hopefully gives you some idea of how these simulations work in general. If you have any questions or want me to elaborate on a specific point, feel free to leave a comment and I will update the post or make a new one when I get the chance!

The post Basic quantum circuit simulation in Python appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post VQE, Excited States, and Quantum Error Suppression appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post VQE, Excited States, and Quantum Error Suppression appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post A quick molecule in Processing.js and Python appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>We’ll use the same format as before, that is a Python string of Processing code, that we modify using the format method. We’ll start with a little bit of Processing setup,

int screen_size = 320; //Screen size in pixels

float rx=0; //Rotation angle for view

float ry=0; //Rotation angle for view

void setup() {{

size(320, 320, P3D);

}}

void draw() {{

translate(width / 4, height / 4, -100);

lights();

background(0);

rotateX(rx);

rotateY(ry);

{}

}}

void mouseDragged() {{

//Add basic click and drag interactivity

rx += (pmouseY-mouseY)*.005;

ry += (pmouseX-mouseX)*-.005;

}}

Which sets us up with a basic 3D scene, and a bit of mouse interactivity. Note that the double braces are for the Python format method to ignore them in replacement. Now we just need to place something functional into the draw() method. For example, we’ll need to be able to draw an atom, which is simple enough

void atom(float x, float y, float z) {{

//Draw an atom centered at (x, y, z)

pushMatrix();

translate(screen_size * x, screen_size * y, screen_size * z);

fill(250);

//noFill();

noStroke();

//stroke(255);

sphere(screen_size * .05);

popMatrix();

}}

and a bond between two points, which takes a bit more code in the Processing style

void bond(float x1, float y1, float z1,

float x2, float y2, float z2) {{

//Draw a bond between (x1,y1,z1) and (x2, y2, z2)

float rho = screen_size * sqrt((x1-x2) * (x1-x2) +

(y1-y2) * (y1-y2) +

(z1-z2) * (z1-z2));

float theta = atan2((y2-y1),(x2-x1));

float phi = acos(screen_size * (z2-z1) / rho);

int sides = 5; //Bond resolution

float bond_radius = .015*screen_size; //Bond radius

float angle = 2 * PI / sides;

pushMatrix();

noStroke();

fill(255);

translate(screen_size * x1, screen_size * y1, screen_size * z1);

rotateZ(theta);

rotateY(phi);

beginShape(TRIANGLE_STRIP);

for (int i = 0; i < sides + 1; i++) {{

float x = cos( i * angle ) * bond_radius;

float y = sin( i * angle ) * bond_radius;

vertex( x, y, 0.0);

vertex( x, y, rho);

}}

endShape(CLOSE);

popMatrix();

}}

With these primitive rendering functions defined, let’s turn to where we get our data and how to prepare it. I’m going to use a simple XYZ list of coordinates for adenine as an example. That is, I have a file adenine.xyz that reads as follows

15 7H-Purin-6-amine N -2.2027 -0.0935 -0.0068 C -0.9319 0.4989 -0.0046 C 0.0032 -0.5640 -0.0064 N -0.7036 -1.7813 -0.0164 C -2.0115 -1.4937 -0.0151 C 1.3811 -0.2282 -0.0017 N 1.7207 1.0926 -0.0252 C 0.7470 2.0612 -0.0194 N -0.5782 1.8297 -0.0072 H 1.0891 3.1044 -0.0278 N 2.4103 -1.1617 0.1252 H -3.0709 0.3774 -0.0035 H -2.8131 -2.2379 -0.0191 H 2.1765 -2.0715 -0.1952 H 3.3110 -0.8521 -0.1580

To render something in Processing3D, the coordinate system starts from 0, and is oriented perhaps in the opposite way that you’d expect. As a result, it’s prudent to load this data in, shift, and rescale it to fit inside a unit cube. Moreover, xyz files don’t contain information about bonds, so we can quickly infer if they might exist based on a distance calculation. There are certainly better ways to do this, and bond distance should depend on atom types, but this works for a quick pass. We can do this in Python as follows:

from IPython.display import HTML

import numpy as np

xyz_filename = 'adenine.xyz'

#Load molecule data from a file

atom_ids = [line.split()[0] for line in open(xyz_filename, 'r') if len(line.split()) > 1]

atom_xyz = np.array([[float(line.split()[1]), float(line.split()[2]), float(line.split()[3])]

for line in open(xyz_filename, 'r') if len(line.split()) > 1])

#Find potential bonds between nearby atoms

bonds = []

bond_cutoff = 1.5**2

for i, atom1 in enumerate(atom_xyz):

for j, atom2 in enumerate(atom_xyz[:i]):

if (np.sum((atom1 - atom2)**2) < bond_cutoff):

bonds.append([i,j])

#Rescale so largest distance between atoms is bounded by 1, and all coordinates start from 0 reference

min_coord, max_coord = np.amin(atom_xyz, axis=0), np.amax(atom_xyz, axis=0)

scale_factor = 1.0/np.sqrt(np.sum((max_coord-min_coord)**2))

translation_factor = np.repeat([min_coord], atom_xyz.shape[0], axis=0)

atom_xyz -= translation_factor

atom_xyz *= scale_factor

From here, all we have to do is prepare a small template string, loop through the atoms and bonds, and render:

atom_template = """

atom({}, {}, {});

"""

bond_template = """

bond({}, {}, {}, {}, {}, {});

"""

#Render bonds that will sit between atoms

bond_code = ""

for bond in bonds:

bond_code += bond_template.format(*np.concatenate((atom_xyz[bond[0]], atom_xyz[bond[1]])))

#Render atoms

atom_code = ""

for i, atom in enumerate(atom_xyz):

atom_code += atom_template.format(*atom)

processing_code = processing_template.format(bond_code + atom_code)

Now we make an HTML template, and ask IPython to render it:

html_template = """

<script type="text/javascript" src="processing.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript">

var processingCode = `{}`;

var myCanvas = document.getElementById("canvas1");

var jsCode = Processing.compile(processingCode);

var processingInstance = new Processing(myCanvas, jsCode);

</script>

<canvas id="canvas1"> </canvas>

"""

html_code = html_template.format(processing_code)

HTML(html_code)

If everything went as planned, hopefully you’ll now have a somewhat crude rendering of adenine to play with and rotate. You could even put it on your webpage with Processing.js if you dump the code to a file like

with open('adenine.pde', 'w') as processing_file:

processing_file.write(processing_code)

which hopefully gives you the crude rendering below (try clicking a dragging)

The post A quick molecule in Processing.js and Python appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Processing.js in an IPython Notebook appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The steps to integrating Processing.js into an IPython notebook locally are as follows.

First, download the processing.min.js file from Here, and place it in the same directory as where you would like your IPython Notebook. No other installation is required. Now import the only IPython function we need, the HTML display function as

from IPython.display import HTML

From here, we define our Processing code as a Python string (I won’t talk about the Processing code itself, but nice tutorials exist for the interested reader).

processing_code = """

int i = 0;

void setup() {

size(400, 400);

stroke(0,0,0,100);

colorMode(HSB);

}

void draw() {

i++;

fill(255 * sin(i / 240.0) * sin(i / 240.0), 200, 175, 50);

ellipse(mouseX, mouseY, 50, 50);

}

"""

One could use Python code to generate this Processing code on the fly from data if desired as well. With the Processing code in place, we need some template to render it. This is where my tweaking came in, as the most obvious solutions based on Processing.js examples failed to render for me. I found that manually calling the compile function fixed my woes however, and only required one or two additional lines of code. So now we define the following HTML template as a Python string as well, with brackets in place for easy substitution.

html_template = """

<script type="text/javascript" src="processing.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript">

var processingCode = `{}`;

var myCanvas = document.getElementById("canvas1");

var jsCode = Processing.compile(processingCode);

var processingInstance = new Processing(myCanvas, jsCode);

</script>

<canvas id="canvas1"> </canvas>

"""

Finally, simply render the Processing code using IPython’s HTML function.

html_code = html_template.format(processing_code) HTML(html_code)

If everything went as planned, you should have the following Processing.js element rendered at the end of your IPython notebook. Play around with it by moving your mouse over the top of the canvas.

The post Processing.js in an IPython Notebook appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Simple bash-parallel commands in python appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>For those reasons, the following short code snippet (and variants thereof) has become surprisingly common in some of my prototyping.

#Process level parallelism for shell commands

import glob

import subprocess as sp

import multiprocessing as mp

def work(in_file):

"""Defines the work unit on an input file"""

sp.call(['program', '{}'.format(in_file), 'other', 'arguments'])

return 0

if __name__ == '__main__':

#Specify files to be worked with typical shell syntax and glob module

file_path = './*.data'

tasks = glob.glob(file_path)

#Set up the parallel task pool to use all available processors

count = mp.cpu_count()

pool = mp.Pool(processes=count)

#Run the jobs

pool.map(work, tasks)

This simple example runs a fictional program called “program” on all the files in the specified path, with any ‘other’ ‘arguments’ you might want as separate items in a list. I like it because it’s trivial to modify and include in a more complex python workflow. Moreover it automatically manages the number of tasks/files assigned to the processors so you don’t have to worry too much about different files taking different amounts of time or weird bash hacks to take advantage of parallelism. It is, of course, up to the user to make sure this is used in cases where correctness won’t be affected by running in parallel, but exploiting simple parallelism is an trivial way to turn a week of computation into a day on a modern desktop with 12 cores. Hopefully someone else finds this useful, and if you have your own solution to this problem, feel free to share it here!

The post Simple bash-parallel commands in python appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Integrating over the unitary group appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>Regardless, one of the tools used in many of these analyses at the moment is integration over the unitary group. This is because the unitary group allows us a way to generate all possible quantum states from some choice of starting state. To complete these analyses one must also integration over the simplices of eigenvalues corresponding to physical states, but for now I want to focus on the unitary group. To talk about integration, we need some way of quantifying volume, or a measure. The unitary group has a natural measure, its unique Haar measure that treats all unitary operators equally. It does this by being invariant under the action of the unitary group, in the same way you wouldn’t want the volume of a box to change if you translated it through space. Mathematically we can phrase this as saying ![]() , which leads to a corresponding Haar integral with the defining property

, which leads to a corresponding Haar integral with the defining property

(1) ![]()

for any integrable function ![]() , group elements

, group elements ![]() , and the last equality is written to match the shorthand commonly found in papers. We should also note that it is convention to fix the normalization of integration over

, and the last equality is written to match the shorthand commonly found in papers. We should also note that it is convention to fix the normalization of integration over ![]() of the identity to be

of the identity to be ![]() . So that’s all very interesting, but something harder to dig up, is how to actually compute that integral for some actual function

. So that’s all very interesting, but something harder to dig up, is how to actually compute that integral for some actual function ![]() that has been given to you, or you find interesting. I’ll show a few options that I’ve come across or thought about, and if you know some more, I’d love it if you would share them with me.

that has been given to you, or you find interesting. I’ll show a few options that I’ve come across or thought about, and if you know some more, I’d love it if you would share them with me.

Integration through invariance

Some integrals over the unitary group can be done using only the invariance property of the Haar integral given above, and reasoning about what it implies. This is best illustrated through an example. Suppose that ![]() , where

, where ![]() indicates Hermitian conjugation, and the integral I am interested in is

indicates Hermitian conjugation, and the integral I am interested in is

(2) ![]()

Now take any ![]() and start using that integral invariance property as

and start using that integral invariance property as

(3) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} VD(X)V^{\dagger} &= V \left[ \int UXU^\dagger dU \right] V^\dagger \notag \\ &= \int (VU)X(VU)^\dagger dU \text{ (By integral linearity)} \notag \\ &= \int UXU^\dagger dU \text{ (By integral invariance)} \notag \\ &= D(X) \end{align*}](https://jarrodmcclean.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-844c2ed1bf8af2fca3db5ee1c2e4e06c_l3.png)

Thus we find that ![]() for all

for all ![]() , implying that

, implying that ![]() . If a matrix is proportional to the identity, then we can characterize it completely by its trace which we then evaluate as

. If a matrix is proportional to the identity, then we can characterize it completely by its trace which we then evaluate as

(4) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} \text{Tr}[D(X)] &= \text{Tr} \left[ \int UXU^\dagger dU \right] \notag \\ &= \int \text{Tr} \left( UXU^\dagger \right) dU \text{ (by integral linearity)} \notag \\ &= \int \text{Tr} \left( X \right) dU \text{ (by cyclic invariance of the trace)} \notag \\ &= \text{Tr}(X) \end{align*}](https://jarrodmcclean.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-17d1d11cdf024550bb17ecff30eac256_l3.png)

From these two results, we conclude that

(5) ![]()

which was evaluated entirely through the defining invariance of the integral.

Monte Carlo Numerical Integration

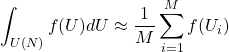

For some problems of interest, there is no obvious way of integrating it analytically or reaching a closed result. In order to perform a numerical integration, one could choose some parameterization and attempt integration with a quadrature, but this is both cumbersome and often runs out of steam as the dimension of the problem of interest grows. Monte Carlo integration offers a straightforward way to at least attempt these integrations for high-dimensional problems of interest, and is often less human work even for low dimensional problems. Monte Carlo integration is simple, and approximates the integral as

(6)

where ![]() is the number of sample points you take, and

is the number of sample points you take, and ![]() is a randomly drawn unitary that is drawn with uniform probability according to the Haar measure. How to draw unitaries uniformly with respect to the Haar measure is not entirely obvious, but luckily this has been worked out, and there are a few ways to do this. One of this requires only

is a randomly drawn unitary that is drawn with uniform probability according to the Haar measure. How to draw unitaries uniformly with respect to the Haar measure is not entirely obvious, but luckily this has been worked out, and there are a few ways to do this. One of this requires only ![]() simple steps available in most modern math libraries that are

simple steps available in most modern math libraries that are

- Fill an

matrix with complex Gaussian IID values, call it

matrix with complex Gaussian IID values, call it  .

. - Perform a QR decomposition of the matrix

, define

, define  to be the diagonal of

to be the diagonal of  such that

such that  and

and  otherwise.

otherwise. - Set

.

.

where ![]() is now the unitary of interest randomly distributed according to the Haar measure on

is now the unitary of interest randomly distributed according to the Haar measure on ![]() . Here is a Python function that can do this for you if the above steps don’t make any sense.

. Here is a Python function that can do this for you if the above steps don’t make any sense.

import numpy as np

import numpy as np

import numpy.random

import scipy as sp

import scipy.linalg

def random_unitary(N):

"""Return a Haar distributed random unitary from U(N)"""

Z = np.random.randn(N,N) + 1.0j * np.random.randn(N,N)

[Q,R] = sp.linalg.qr(Z)

D = np.diag(np.diagonal(R) / np.abs(np.diagonal(R)))

return np.dot(Q, D)

Weyl’s Integration Formula

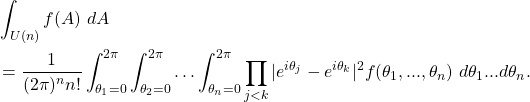

This formula is a bit of a sledge hammer for hanging a nail, but it exists for all compact Lie groups and for the unitary group takes on the specific form

(7)

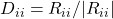

This formula also demands that ![]() be a conjugacy invariant function on the unitary group as well as symmetric in its arguments. The

be a conjugacy invariant function on the unitary group as well as symmetric in its arguments. The ![]() correspond to the possible eigenvalues that characterize all unitary matrices. I’ve yet to use it for a practical calculation, but like having a catalog of known options.

correspond to the possible eigenvalues that characterize all unitary matrices. I’ve yet to use it for a practical calculation, but like having a catalog of known options.

Elementwise Integration up to the Second Moment

Often, one is interested only in integration of some low-order moment of the Haar distribution, in which case simpler formulas exist. In particular, if the integral depends only on the ![]() ‘th power of the matrix elements of

‘th power of the matrix elements of ![]() and

and ![]() ‘th power of the matrix elements of its complex conjugate

‘th power of the matrix elements of its complex conjugate ![]() , then it suffices to consider a

, then it suffices to consider a ![]() -design. Moreover, the explicit formulas for integration take a simple form. In particular, up to the first moment we have

-design. Moreover, the explicit formulas for integration take a simple form. In particular, up to the first moment we have

(8) ![]()

which can be used to evaluate the same formula we evaluated above through invariance. That is, we seek

(9) ![]()

which we can evaluate by each element

(10) ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \begin{align*} [M]_{im} &= \sum_{j,k} \int dU \ U_{ij} \rho_{jk} U_{km}^\dagger \\ &= \sum_{j,k} \rho_{jk} \int dU \ U_{ij} U_{km}^\dagger \\ &= \sum_{j,k} \rho_{jk} \int dU \ U_{ij} U^*_{mk} \\ &= \sum_{j,k} \rho_{jk} \frac{\delta_{im} \delta_{jk}}{N} \\ &= \sum_{j} \rho_{jj} \frac{\delta_{im}}{N} \\ &= \tr \rho \frac{\delta_{im}}{N} \end{align*}](https://jarrodmcclean.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-3d0dea5dfc937f97cf7e531950dab428_l3.png)

using the second delta function we find the full matrix representation of ![]() is given by

is given by

(11) ![]()

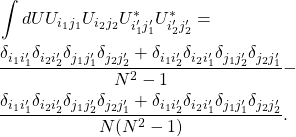

which is the result we obtained above through invariance. Similarly the formula for second order can be expressed simply as

(12)

Edit 3/20/18: Thanks to Yigit Subasi for pointing out that my Python implementation depended on the algorithm implementing the QR decomposition, and that a simple change made it independent of the method. It is now updated to reflect this fact. I also added the elementwise evaluation for integration over the Haar measure up to the second moment.

The post Integrating over the unitary group appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Expressive power, deep learning, and tensors appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post Expressive power, deep learning, and tensors appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>The post A new paper on the VQE appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>Given the excitement around this algorithm as a potential candidate for a first algorithm to become competitive with a classical computer at scale, we wanted to expand a bit more on our views of the theory and purpose of this algorithm, as well as offer some computational enhancements. We did just this in our new paper entitled “The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms”, and we hope you enjoy reading it as much as we enjoyed writing it.

The post A new paper on the VQE appeared first on Jarrod McClean.

]]>