| CARVIEW |

Some themes and resources in this talk are consistent with the Social Justice Summit posts I shared some time ago, but stick with it and the content will diverge/clarify. The video is below and you can see the slide deck if desired. A reference/works consulted list follows at the end.

For the Greater (Not) Good (Enough): Open Access and Information Privilege

The title of my talk is For the Greater (Not) Good (Enough): Open Access and Information Privilege. This is a lot of heavy stuff, right? Open access (OA) is a huge topic, information privilege is a huge topic. What I want to do is begin with an image that I think can sum up how I’m going to come at these two giant ideas, both of which can be a little – let’s face it – depressing.

This is one of my favorite images. I took it in West Texas – I’m from Texas originally. I was driving through this little tiny ghost town on a sad highway, and the oil industry had dried up at this point – this was about 10-12 years ago. There was a lot of economic degradation, and you could tell there were not many opportunities available. Yet there was an old sign printing shop that somehow, someone had taken the time – in this store that didn’t even look like it was operating – to put up this message (“happiness is attainable”) letter by letter even though the thing’s rusted and the town’s falling apart.

The incongruity of this has always struck me as amazing. It’s it’s a way to encourage ourselves to acknowledge that there are hard things but that there are also very positive, resilient messages that can be seen within the challenging spaces. So remember that sign no matter how heavy I get. I promise that I’ll wrap it back around to this place by the end of the presentation.

Before I get any further I want to say so many thanks to OCLC for having me here – to Rachel (Frick) of course – Lorcan (Dempsey). Also, Nancy Lenssenmayer is literally the most effective person I have ever worked with in my life. She’s amazing. Thank you, Nancy. I also want to thank all the people who came today, all the people who are online spending the time to listen to this talk and hopefully ask some good questions after I’m done spewing up here. And thanks of course to all the people who have inspired this presentation. There have been a lot of scholarly communications librarians that I’ve worked with over the course of my life – I am not one – and I’ll talk a little bit about that in a moment. First off, of course Carmen Mitchell at my own institution, CSU San Marcos. I have learned a lot from her. I also want to give a shout out to Amy Buckland, and also to Allegra Swift who works at UCSD. Thank you for all the learning that you’ve helped me do in preparation.

Back to the presentation. It’s wonderful to be invited to this series. As Rachel mentioned, I started my career at Ohio University as a librarian. It was my first job, and this is the cabin that I lived in the woods in the complete sticks north of Athens [referring to slide 8]. I loved it there. One of the things that was interesting about having this as a first job is that I was indoctrinated into the collaborative library culture of Ohio, which is fierce. For those of you who have been here for a long time I see some head nods – OCLC was established back when the first word in its name was “Ohio” to begin a process of harnessing collective energy through collaborative cataloging. The library I was in had memories of that as OCLC’s original role. That harnessing of the collective energy of our profession is something that is very central to what I’m talking about today. The need for it and the continuation of it, particularly in a non-profit space, and a space that does not have a profit imperative or a profit motive. Because we are libraries and librarians, and we do not work for profit… we work for the greater good. The public good.

I also wanted to say thanks for stressing me out by calling this the “distinguished” seminar series. I’m following two people that I respect very much – Trevor Dawes and Dr. Kim Christen. I watched their presentations; they were excellent. So all I’m going to try to do today is bring as much energy and insight as they did to this stage, and hopefully address any questions you have to continue this dialogue. It’s a little bit stressful but I’m also honored, so I’m gonna bring it. I promise.

One good thing about being “distinguished” is that you get to get up on a stage and talk about what matters to you. I use this image [referring to slide 10] a lot of presentations because I think it’s very evocative of the way that I tend to approach opportunities like this. I like to get up on my soapbox and holler – not quite holler exactly, but I love to discuss ideas that are challenging to our profession, that are important to the public good. And because I’m up here y’all have to listen to me, so here we go.

The funny thing in my preparation for this presentation – and I already mentioned this – is that I’m not a scholarly communications librarian. I have done a lot of things in my library career, but this topic is not my precise area of expertise. I took a picture of the coffee table in my hotel room this morning to give y’all a sense of how much I’ve been cramming for this for this talk.

It’s been a fascinating journey. It’s confirmed a lot of my assumptions about how OA interacts with information privilege. And it’s also tested a lot of my assumptions, taught me many things I did not know, and has given rise to some ideas that I want to throw out there that I think might be interesting.

So where do I come from in libraries? I’m a teacher. I started off as a Reference & Instruction librarian at Ohio University. This is the primary perspective I tend to bring to my work, teaching and learning, information literacy and how to challenge people to use their noodles (for lack of a better word). For the last five-to-seven years I’ve been in management and administration: I used to focus on learning exclusively, and now it’s about how to get things done and use the tools at our disposal in libraries to be sustainable and above all else support our students. And that’s where I get my inspiration, that last line – supporting students. Student learning is my primary motivation and it’s something that grounds the ideas I want to share with you today. So that’s where I get my fire.

I want to establish a central premise for this talk – it’s something that I’ve alluded to a couple of times already. This is a quote from OA advocate John Wilinsky:

“Access to knowledge is a human right that is closely associated with the ability to defend as well as advocate for other rights.”

For context, he’s won awards from SPARC, a foundation that deals with the promotion and proliferation of OA, and wrote a book called The Access Principle in 2006 that I recommend to people. It’s free, no surprise there.

I think this quote is a perfect encapsulation of how I want to come at the the two topics of OA and information privilege. This should simply be true for people in our field. Information professionals, librarians, knowledge workers – our work is predicated upon this idea. I hold it very strongly and I hope that you do too.

I want to give you quick definitions of these two concepts before I go any further. Information privilege is a relatively simple idea. Privilege itself means that – just to give you an example – I’m standing up here with my fancy shoes and I had a great breakfast and I got flown out here by OCLC, which I’m very grateful for… these are incredible advantages that I have had and accumulated over the course of my life. There was some hard work in there but the way I look, where I come from, the educational opportunities I had, the white middle-class background that I grew up in – that is the accumulation of my privilege, and I use it and I feel it every day.

Transfer that concept to the the area of information access, and people who are poor, people who are minoritized, people who are incarcerated, people who don’t have an institutional affiliation with a particular school, or have a public library close to them that offers anything like free interlibrary loan: these people are are information underprivileged, information impoverished. And OA – for this audience I don’t need to be defining it at length, but I do like the Budapest Open Access Initiative‘s definition as “the right of users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full text of content.” So, not having to pay for stuff in the simplest words possible.

Like I mentioned at the beginning, these are huge concepts. At the stratospheric level ideas of OA and information privilege can seem a little bit oblique… confusing… not really that tangible. What I want to do is bring these things down closer and closer to earth, to the point at which people who work in libraries – maybe if these aren’t your motivating factors yet – can begin to grapple with them on the ground and put activities into action that can actually help manifest more information equity and more OA that is truly open. I’ll get to that little qualifier by the end – how open is open? It’s a good question.

I like to tell stories, and I like to speak for myself. So from my own vantage point I’m going to tell you a couple of vignettes that illustrate what information privilege looks like, what information underprivilege looks like, the responsibilities of the former, and the negative effects of the latter.

I’ve lived all over the country and have had a lot of jobs – I like to move around. What I really want to talk about is the way that I was raised. That’s my mom – she’s amazing – I hope she’s watching (sometimes she is). Once Rachel [Frick] invited me to give the keynote at the 2013 Digital Library Federation conference in Austin: my mom lives in there, and she was in the audience smiling. My mom raised me with a real love of learning – she was an ESL teacher at the college level, a Spanish teacher at the college level, and she raised her kids to be autodidacts – to know how to teach ourselves. The way she did this was to instill in us an absolute love of libraries and reading.

At the same time, living in Texas I had a very difficult experience growing up. Being a queer person, I came out very young and was in a very conservative place. The instant I could liberate myself I shot across the country at light speed and landed in Portland, Oregon at Reed College, a place that encapsulated what I wanted in furthering my education. It was an extremely rigorous, self-directed, maniacally difficult place to study. Here’s another aspect of my privilege – this was expensive. I had help, and without it I wouldn’t have been able to get out of the bad situation I was in. So I’m grateful for that.

I go back home to Austin and begin the process of getting my library degree at UT, learning how to do the work. I had the opportunity to work at Perry-Castañeda Library, and shout out to all my colleagues there. At the same time I started to do the thing that sometimes one does when they’re surrounded by a community of activists and artists – I started to develop more of a political consciousness. This was growing in me from my experiences as a queer person who experienced a lot of trouble based on my identity. Combining social justice activism and libraries led me to work with a books to prisoners project called Inside Books.

Prison libraries are an established sector of our profession, but unfortunately are shrinking with the privatization of incarceration, wherein “special programs” focused on education and literacy are often eliminated. Those special programs are essential to prisoners who not only have to spend their time in these horrible boxes, but need to be able to advocate for themselves in and through the judicial system. A number of court cases enshrined the right to access to prison libraries and then knocked it back down again[1]. Prison libraries have been in trouble for a long time, and for that reason there are organizations across the country (and I assume across the world) that have programs for distributing reading material to incarcerated folks.

At Inside Books we received letters from all over prisons in Texas with notes that would say, “I’d really like this kind of book, can you please send me xyz?” We’d get requests for Spanish-language dictionaries, westerns, romance novels, chemistry textbooks – anything under the sun – and we would fulfill those requests, write a note back, and mail it off. What was so unfortunate is that a lot of the items got returned for no reason. We’d pay postage to put these books in the mail, they’d go to the prisons, and for some arbitrary reason a lot of them would get kicked back to us with “return to sender” without any rationale.

For these incarcerated people, even when external actors were trying to support them with direct donations, disenfranchisement was going on. Systematic rejection of reading materials for prisoners because… why? It’s dangerous? You tell me. The systematic rejection of books to prisoners work is an excellent example of information poverty, a concept that’s been discussed at length in our profession. It’s not just about information privilege – the flip side is that some people just simply can’t get access to the knowledge that they need in order to be able to advocate for justice for themselves and others.

Switching gears, going back to Ohio where I’m standing now. A lot of information poverty has to do with isolation. When I lived in the woods in Ohio, I had my fancy library job but I was trying to complete an online degree at the time and that house didn’t have internet. I don’t even think we could get dial-up out there. So I was like okay, online degree and no internet: this is going to be interesting. I would load up a laptop at the end of my workday with all the tabs I needed to read, and I would go home and think to myself “I hope nothing crashes” and attempt to write out my assignments in Word and then paste them into the discussion forums the next day. This is the most vanilla example of information underprivilege possible, but it goes to show you that being incarcerated isn’t the only way to not have information privilege. If you are isolated, if you live in a rural community, if you do not have proximity to libraries that have robust collections, or if you’re in communities that are having their public library budgets cut.

I wanted to tell my favorite story about triumph over information isolation. This individual [Sandor Katz] is someone I met while doing the Inside Books volunteer work – this person lived on a radical fairy land trust in the middle of nowhere in Tennessee, and his thing is fermentation. He was also ill, especially at the time that he was on this journey of figuring out how to ferment foods, and teaching other people how to do it – trying to figure out how to keep his gut bacteria healthy and feel better. This individual also has a huge brain and a lot of curiosity, so over the course of this work of figuring out how to make different kinds of fermented food he realized that a lot of the articles he needed weren’t going to be available to them, particularly not in his isolation in the woods. Over the course of his travels he had interacted with librarians, so I started getting emails from him years ago saying, “hey Char, can you maybe find me this article from the Journal of Viral Bacteriology?” or whatever. And because I was at Berkeley I was like “yeah, I’ll just send it to you.” If he hadn’t had those connections with librarians across the country to begin to lift these paywalls for him, he never would have been able to do this incredible thing that he ended up doing, which was writing a New York Times bestselling book called The Art of Fermentation, which some of you have probably read.

Okay, let’s return to an important point. This individual had to ask librarians to literally break the law for him in order to produce that book. A point I’m going to come back to again is that even though it’s ten years after this example and the OA movement has made so much progress, the same situation still exists: this is what we need to work on. And of course Sandy outed every single librarian who had helped him in his acknowledgments, which is rad because it just goes to show what we’re about and the lengths we’ll to go to to help people get that information that they need.

We have information privilege, and how are we going to use it? A good way to think about this kind of work is to:

“explain what is wrong with current social reality, identify the actors to change it, and provide achievable, attainable, practical goals for social transformation.” – James Bowman

This is a mode of thinking that helps you analyze and deconstruct power and privilege and the intersectionality of different identities that give people more and less power, more and less privilege. I like this allegory to library and information work. In order to understand and act upon a situation like Sandy’s, we need to be able to explain what is wrong (and let’s face it, there’s a lot wrong) with current social reality, identify the actors to change it, and provide achievable, attainable, practical goals for social transformation.

This is our mission, and this is what I’m going to be talking about for the rest of the presentation. How do we do this? What does this look like, and how do these two massive stratospheric ideas of OA and information privilege collide toward this goal? I’m already twenty minutes in, and because I could talk about this stuff literally until you all fall asleep and/or die I’m going to focus it down.

A thing I like to do when I’m confronted with this impossible of a topic is ask myself hard questions, which helps focus on the most meaningful things to engage during this limited amount of time we have together. The first question is important – why do we do this work? I hope that you have a good answer to this question. Think about it. I’ve begun to tell you why I do this work, but I challenge you to think about your own motivations for the energy that you put in when you’re not sitting in these chairs. Equally and more important, what values are most important to our communities? We’re libraries, and the reason we exist is to hold a mirror up to our communities and augment everything that they are and need. We should match the people we serve. We should see them, value them, and give them the things they need to thrive and be able to advocate.

And my favorite question of all – what’s broken that we can help mend or fix? I have a brilliant friend named Pascal Emmer. He’s an amazing activist and human being, and also happens to be a ceramicist that makes objects I can’t quite believe are possible. Every once in a while Pascal will fire something that explodes. This is a thing that happens to people who make pottery – my wife Lia, she’s also a ceramicist and I’ve seen her lament many an exploded piece over the course of our marriage. But that just part of it. There’s a beautiful Japanese ceramics technique called kintsugi – if your piece breaks in such a way, instead of only gluing it together you can paint the cracks over with gold to highlight the flaws. In order to make it that much more beautiful.

I want to use this broken object with obvious flaws as a metaphor for the work that we can do around information privilege and OA. I want to characterize it with this phrase – “the politics of and imperfection and responsibility.” An article came out recently by Frances Lee called Why I’ve started to fear my social with my fellow social justice activists. What this article talks about is an ethics of activism. We’re all imperfect. Our institutions are imperfect, every single thing is imperfect. We have to be able to recognize imperfection, see the cracks, and then take responsibility for fixing them. Not only fixing them, but highlighting the work that we did to fix them. Which is where the kintsugi metaphor comes back in: we want to demonstrate the brilliance of what has been broken and been put back together.

Now I get to talk about CSU San Marcos, which is a place I love very much. This is my library – it’s a huge beautiful new building and I, for most of my career, have worked in older crappy libraries that were falling apart bit by bit. It feels incredible to be in a facility that is operational, and shiny, with the carpets that are, like, decent. Tt’s great, but that’s not all there is to it. The thing about the students that I work with, and the students that the CSU system as a whole serves, is that these are students who have been minoritized for many reasons: poor students, underrepresented students. We’re an Hispanic Serving Institution with a large proportion Pell Grant recipients. It’s because of those factors that information underprivilege is a fact of life. It’s just a reality. A lot of the work that we do at my institution is geared towards what kind of economic impact that we can have on our students’ educational experience in order to help them persist.

I want to acknowledge and attribute Carmen Mitchell, who I gave a shout out to earlier. This image [of sticky notes on a whiteboard] is part of the #textbookbroke campaign that started a couple of years ago – Carmen worked on this at CSUSM. A lot of people are wise to the fact that textbooks are too expensive. Students cannot afford them, and sometimes drop out of school because of the cost. Students don’t get the textbooks they need for classes, and therefore their experience and performance is affected. So, we put up whiteboards in the entrance of our library and asked this question – “what would you be able to afford if you didn’t have to buy your textbooks?” We got hundreds of responses. Carmen did an analysis and a bit of visualization, and what we saw is things like this: “new teeth, food, housing, gas, rent”. These are basic human needs, and these are what our students have to forego – not just our students but many students in this country and internationally – in order to afford the materials of their education.

There’s a professor at CSU San Marcos that I respect named Jill Weigt, and in preparation for a panel on food insecurity she created an extra credit assignment in one of her classes. She asked students (and these were second year sophomores) “What are the three barriers to your academic success? What do you want to call out as the hardest things that confront you?” Without fail, things like “due losing my job I became homeless”, “I lack transportation”, “I was paroled from prison and I had to do all these parole things and I couldn’t make it to class,” “family obligations at home”, “stress and allocating finances to pay for school”, and, simplest of all: “culture, race, economic background.” This is reality, and as librarians and people who work in the world of information we should be focused on fixing this, because it is killing our students.

Students are experiencing external challenges, and, frankly, violence. We’re finding white supremacist recruitment posters all over my campus – these organizations are targeting schools that have a lot of underrepresented minorities. Our students are challenged from so many structural directions that they cannot control, and now this on top of all of it? It’s crushing, and it has a lot of synchronicity with the topic at hand. “Fake news”, the warping of the idea of truth itself, is feeding into this culture, and that culture is feeding into our institutions. I think libraries have the responsibility to help stem this tide, and speaking of responsibility — thanks to OCLC for my speaking fee. I donated it to an organization called Life after Hate. If anyone is interested in supporting a group that helps people who have been white supremacists rehabilitate themselves, please give them money. They were slated to get a huge federal grant a few years ago, but in the new administration that grant got cancelled, so they need money.

So can we all agree that there are cracks in the system? Can we all agree that it’s our responsibility to shine a light on these cracks and try to make them beautiful when we fix them? Excellent, I’m hearing lots of “yeses”. If the principle of our institutions is that “libraries are for everyone”, if our Bill of Rights says that libraries are about access, advocacy, openness, freedom, and inquiry, we have to acknowledge the flipside. This is the piece of the “happiness is attainable” sign that’s covered in rust. Libraries have a history of – and this was addressed in Kim Christen’s talk before me – encouraging assimilation of different cultures into American culture, of perpetuating colonialism, of being party to censorship that still happens today, biased description in our cataloging and metadata, and frankly complicity – we segregated. And the way this behavior comes out today is often in the form of fees, fines, polices, “neutrality,” and apathy on the part of library employees.

What can we possibly do to attack these big problems? Well, it’s simple – we identify and overcome the barriers that we perceive, systematically, in our institutions for our communities on the ground. I gave a talk recently at this event at CSUSM called the Social Justice Summit. It’s a group of 40 students at CSU San Marcos who sign up for an intensive three-day training in how to be effective activists. It’s about communication, fundamentals of social justice theory and criticism, and just generally being awesome. These people were very inspiring to me, and what I talked to them about is how libraries can act as allies to them, how the library itself can be an institutional ally. I want to give a couple of quick examples of the way we’re doing this at CSU San Marcos, and again this is not “my” work, this is the work of the collective and it’s something that’s very important to acknowledge. It’s never just about an individual in libraries.

So if money’s part of the barrier, what can we do? One of the proudest things that I’ve done at San Marcos is blow open the wage structure for Student Assistants at our library. Student Assistants do a huge amount of the work in libraries, and they often get paid poor wages. Federal Work Study farm, does that sound familiar than anyone? Yeah, no. That’s not cool. Our campus didn’t really allow us to give raises to students unless they’d worked a certain number of hours, and so I in my administrative privilege became very annoying to our Human Resources office and forced them to rethink because of my polite persistence about asking, Can’t we give merit raises? Can’t we hire people at at different rates?? The answer was no, but now it’s changed for the whole campus. I didn’t know that’s what was going to happen, but it’s a great thing. If you administrators out there don’t think you can do anything, you’re wrong.

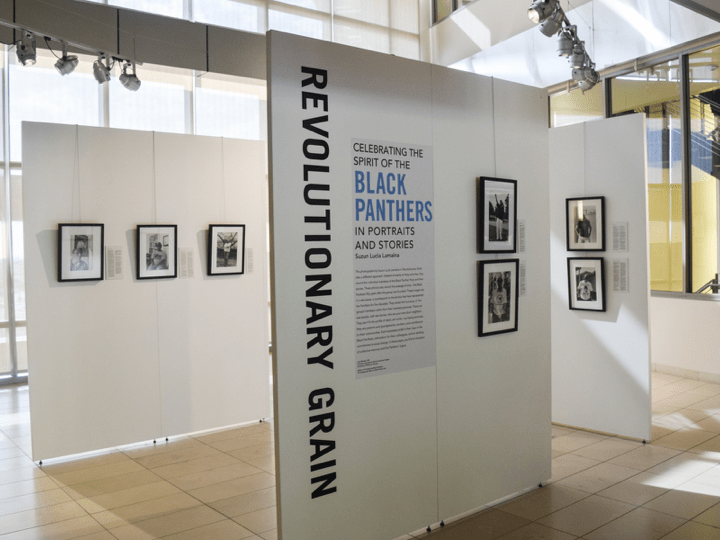

And of course, affordable learning materials programs. Again, a hat tip to Carmen Mitchell. Being able to figure out ways to save our students money on textbooks, including the library renting them for a semester and checking them out on reserve. Also, eliminating fines and fees – this is a big one. We still charge people when books are lost, but why are you going to penalize someone for having a book too long? If it’s not lost, we don’t need to do that. Opening a 24 hour area in our library – this is a student-funded initiative: our student government ran a ballot referendum that pays for it. Based on the data that shows that 20% of our students are housing insecure and up to 50% of our students have experienced food insecurity, we have food, we have a comfortable situation in there and trying to make that that space as hospitable as possible. Other things we’re doing include attempting to have arts and culture programs that are representative of minoritized identities. We recently featured a Black Panthers exhibit, and hat tip to Mel Chu, Talitha Matlin, and Kate Crocker for the awesome work they did on it. We make sure that our Common Read books are representative of diverse identities and challenging topics, and are also trying to get some mural art in our building that will align with the muralist culture and tradition in San Diego.

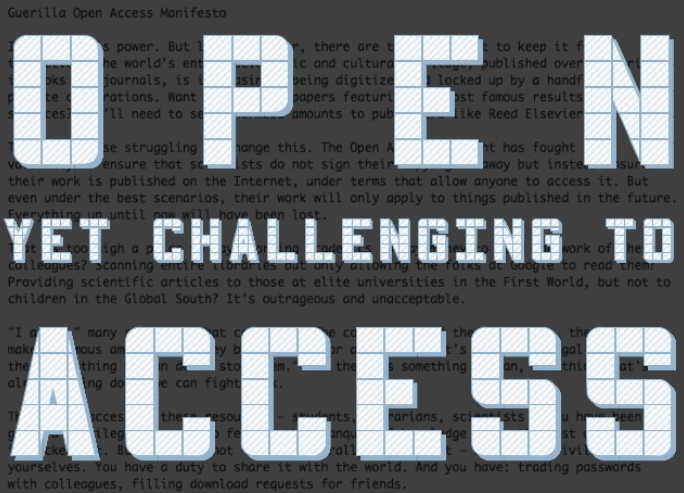

Those are the on-the-ground examples that I wanted to give about the idea of an information justice that comes from libraries, from the work that we do on the ground, and the way that we perceive our users. This idea of information justice is a familiar one to libraries and librarians and people who work in allied nonprofit fields, and it is absolutely essential to integrate this with the idea of OA itself. I’m not going to regale you with all the figures about how many materials are published OA and how much content is available – it’s a lot. So much work has been done to create repositories where people can self-archive their content, to create advocacy organizations that promote legislation such as FASTR that mandate that people who have state or federally funded research deposit their work so that the public can find it. I do think it’s important to acknowledge the most important voices in the OA movement, including Aaron Swartz, who was famously arrested in 2011 for downloading ton of JSTOR articles at MIT, and then, extremely tragically, took his own life in 2013. Some people associate that with the legal trouble he got in, and while I cannot speak for him it was a tragic event. Aaron has this quote that I think draws us right back to our responsibility as librarians and people with so much access privilege ourselves:

“Those with access to these resources — students, librarians, scientists — you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out… But you need not — indeed, morally, you cannot — keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world.”– Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto, 2008

We have a moral obligation to share the information we have access to, and to determine how it can be shared most effectively.

In my teaching I’ve found that information literacy doesn’t resonate strongly with students unless I connect it to information privilege. I think it is fascinating that after years of teaching to people who are basically falling asleep in classrooms, the second I started talking about money – how if you’re at this school we pay x million dollars so you can have access to y amount of content, and once you’re out of here you’re cut off – they start listening. Then it becomes a structural, systemic, societal issue. This is important for the interventions we can come up with to create an effective and pervasive OA information culture. We need to be able to leverage the policy and legislation initiatives that are happening such as FASTR, which I mentioned – discovery platforms such as the DOAJ which has something like 2.6 million articles at this point from 10,000 certified legitimate non-predatory journals. Open educational resources, which I’ve talked about a couple of times. And of course digitized collections such as Hathi Trust and the Digital Public Library of America. These are quick examples, because it would take me three days to talk about all the good content that’s being developed.

But here’s where it gets dark – we have to talk about the flip side. It’s estimated that by now about 25 percent of all the academic scholarly content that’s published is available in some form of OA, and that’s that’s huge. But it still means 75% of the content is behind a paywall. Over 700 mandated OA publishing agreements have been created by research organizations institutions that basically force their faculty to put items in OA repositories or to publish gold OA (which is paying an article processing charge). Unfortunately, even with that, only 25% of content is OA, and libraries in this country still spend 3 billion dollars a year paying the top five publishers for their huge profit margins. This is an amazing statistic: since the rise of OA content (say around 2010) the profit margins of publishers like Elsevier, Blackwell, and Wiley have gone up 10%. Their margins started at 30% and now they’re hovering around 40% – this makes inverse proportional sense. What it means is that there’s a there’s a co-opting of OA by these monster publishers. It highlights a pressing need in our field and allied fields – nonprofit, information-focused fields – to figure out why publishers are profiting so much from OA content, and how it is that a larger and larger share of our purchasing budgets are going to them.

Now that I’m an administrator I truly see the impact this has on our institution. We want to be able to hire more teaching faculty, we want to be able to do more cultural and public programming, but we’re curtailed by the meteoric inflation rise like everyone else. This doesn’t only affect academic institutions. I wanted to quote Roger Schonfeld of Ithaka S&R – “publishers appear to have largely co-opted open access… there’s little evidence that a way has led to decreased licensing expenditures, and it is almost certainly led to a boom at least for the short term in content revenues for some of the largest publishers.” So if journal content prices have outpaced inflation by 250% in the last 30 years – this is intense – what are we going to do about it? And what are other people doing about it out there in the world?

I’ll tell you one thing they’re doing: they’re pirating the hell out of it. Does anyone know who this is this is? It’s Alexandra Elbakyan. She’s the neuroscientist who invented SciHub. There’s a movement on Twitter called #icanhazpdf, which is like an army of Sandys requesting PDFs from colleagues and people trading articles informally online. Along comes Alexandra Elbakyan, who and invents a way to steal 50 million academic articles and make them freely available on the open web. The programming behind this is so diabolical that it’s ingenious. The program is pilfering our own licensed content and adding it to SciHub. There’s an allied site called Library Genesis that has two million volumes of mostly humanities content. Of course SciHub and Library Genesis get a lot of challenges from publishers in the form of lawsuits. One in 2015 ordered SCI hub to come down – it went down and came right back up at about two weeks under a different domain.

Academics are grappling with what it means to have all this pirated content out there, and our relationship to these movements that are literally trying to free information but doing so in very much illegal and illegitimate ways. I encourage anyone who’s interested in this topic to read Who’s downloading pirated papers? Everyone, which came out in Science. It shares statistics like the fact that 28 million papers were downloaded from SCI hub over a period of six months in 2016, that fifty million papers have been indexed by that date – and here’s the most important part for librarians – a lot of this activity is happening at our colleges and universities, in our buildings. They created a heat map analysis of where the highest number of downloads are happening – near and at major research universities around the world and in the United States. Think about that for a minute. Three billion dollars annual in annual expenditures on journal content, and there are folks on our own campuses downloading illegally for free. Why? Because it’s easy. Because it’s discoverable, because there’s one place – only one place – that they have to go to search and download instantly. It’s illegal, but it’s easy.

I think this points to a huge challenge – and also a huge opportunity – for libraries and the organizations that work with us, to address this problem. Closed content is more readily available than the content we license. The open content we license is so challenging to access. Also, the legitimate OA content is challenging to access – because of all of those repositories and discovery tools and layers, it’s basically diffused throughout the universe. I had to do so much research for this presentation (and I’m a librarian) just to figure out what these things are called. ROAR, SOAR, etc. – I imagined being an undergraduate student basically standing out in the woods saying, “what is this? What am I searching? It’s still very confusing. I don’t mean to knock any of the efforts that have been done around OA to date. That said, I don’t think that we have yet addressed this challenge: why is the illegal stuff so much easier to get to than A) our own licensed content and B) the open content that’s sitting around in repositories, paid for through exorbitant article processing charges (APCs)? This is indeed a big challenge, and we need to figure out how to solve it.

I wanted to profile a couple of people who are already doing this – shout out to Open Access Button. We’re evaluating our interlibrary loan workflows using this tool, which is kindof like a legal analogue to SciHub. It crawls green open access publications (which of course are the ones that people self archive as opposed to gold, wherein publishers making something OA funded by APCs. The OA Button is great because if you click it and the article that you’re searching for (using a DOI or a title) isn’t available, they have a workflow that seeks out and pings that author who created the content it tries to guilt-trip them into making it available. It works. I looked through the requests and there’s a bunch of them that are successful. You can see who’s denied and who’s pending, and librarians can contribute to this project.

There are other services that do similar work, like OAdoi. There’s a SFX discovery layer that can help prioritize and push up away content in a library’s own holdings, but we still come back to this idea that these tools only cover about half of the OA universe – only the green content, only the things that article that authors have taken upon themselves to archive. Not the gold stuff, the stuff that the publishers have figured out how to co-opt and produce, the stuff that Roger Schonfeld was talking about. We need to figure out as a collective how to tackle this problem. How to have a discovery tool, layers, methods, workflows, and funding infrastructures that allow us to represent easily and in readily available sources the entire universe of OA content. This is the way to actually and actively combat information privilege especially, in our academic institutions.

So how does it happen? There has been good work done on this question. John Wenzler describes the issue as the “collective action dilemma.” This is one of the barriers that he sees to why libraries haven’t solved this problem yet. It’s the tragedy of the commons: who’s going to pay for it, who’s going to organize it, who’s going to make this work sustainable. K | N consultants – that’s Rebecca Kinnison and Karen Norburg – created a whitepaper that proposes how to revitalize and change the infrastructure of scholarly communication via institutions paying flat annual fees into a giant pool. They did the math in this huge spreadsheet – it’s beautiful – with the price breakdown for the thousand schools they index, and it comes out to about sixty million dollars annually. So instead of paying increasing inflation charges, maybe we can start banding together privileged OA content creation tools that actually help people discover this content easily. This will give us more leverage to negotiate with publishers who keep jacking up prices, and help give people OA content that they’ll actually be able to keep after they leave our institutions.

If there’s a collective action dilemma, then we have to work together to solve it. This work is ongoing, and the content foundation of OA has been laid and is here to stay. There are thousands of repositories and hundreds of agreements helping authors archive, but discovery is still a problem. It’s so much of a problem that our own faculty can’t even figure it out, and they go through more nefarious means to get their information.

To wrap up: if we acknowledge the politics of imperfection and responsibility, if we’re looking for cracks in the system and ways to take responsibility for and challenge information privilege and information poverty by creating a reliable and sustainable infrastructure for OA, then we have to use the same logic that libraries around the world do: figure out how to help patrons overcome the barriers in their lives. If discovery is a problem, if collective action is a problem, who’s going to take up the charge? This is a question we’re still trying to answer, but it’s all geared towards the end goal I began with: information equity.

To close on a positive note, I wanted to give it quote from Toni Morrison. This is where I try to eject you from your seats so you run back to your desks get this thing done, right now:

“When you get these jobs that you’ve been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.” – Toni Morrison

And that is my presentation.

[1] Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817 (1977), mandated that prisons provide incarcerated people with access to legal professionals or law library collections – this preserved the right of “meaningful access to the courts.” Lewis v. Casey, 518 U.S. 343 (1996), rolled this requirement back. A discussion of impacts of these cases and other trends in US prison libraries is available in Lehmann, V. (2011). Challenges and accomplishments in U.S. prison libraries. Library Trends, 59(3), p. 490–508.

References/Works Consulted:

Bergstrom, T. C., Courant, P. N., McAfee, R. P., & Williams, M. A. (2014). Evaluating big deal journal bundles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(26), 9425-9430. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/111/26/9425.full.pdf

Bohannon, J. (2016). Who’s downloading pirated papers? Everyone. Science, 352(6285), 508-512.

Britz, J. J. (2004). To know or not to know: A moral reflection on information poverty. Journal of Information Science, 30(3), 192-204. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0165551504044666

Cope, J. (2016). The labor of informational democracy: A library and information science framework for evaluating the democratic potential in socially-generated information. In B. Mehra & K. Rioux (Eds.), Progressive community action: Critical theory and social justice in library and information science. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed. (Ramos, M. B., Trans.). London: Penguin Books.

Gardner, C. C., & Gardner, G. J. (2015). Bypassing interlibrary loan via Twitter: An exploration of #icanhazpdf requests. In Proceedings of ACRL 2015. Portland, Oregon, March 25-28, 2015. Retrieved from https://eprints.rclis.org/24847/

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Kennison, R., & Norberg, L. (2014). A scalable and sustainable approach to open access publishing and archiving for humanities and social sciences. A white paper. New York: K|N Consultants. Retrieved from https:// https://knconsultants.org/toward-a-sustainable-approach-to-open-access-publishing-and-archiving/

Land, R., Meyer, J. H. F., & Smith, J. (Eds.) (2008). Threshold concepts within the disciplines. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. Retrieved from https://www.sensepublishers.com/media/1179-threshold-concepts-within-the-disciplines.pdf

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Mongeon, P. (2015). The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLoS ONE, 10(6): e0127502. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502

Lewis, D. W. (2017). The 2.5% commitment. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1805/14063

Ruff, C. (2016). Librarians find themselves caught between journal pirates and publishers. The Chronicle of Higher Education 62(24). Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Librarians-Find-Themselves/235353

Schonfeld, R. (2017). Red light, green light: Aligning the library to support licensing. Ithaka S+R, Issue Brief. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.304419

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/sites/default/files/9780262517638_Open_Access_PDF_Version.pdf

Swartz, A. (2008). Guerilla open access manifesto [Online resource]. Retrieved from https://openscience.ens.fr/DECLARATIONS/2008_07_01_Aaron_Swartz_Open_Access_Manifesto.pdf

Tennant, J. P., Waldner, F., Jacques, D. C., Masuzzo, P., Collister, L. B., & Hartgerink, C. H. (2016). The academic, economic and societal impacts of open access: An evidence-based review. F1000Research, 5. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4837983/

Wenzler, J. M. (2017). Scholarly communication and the dilemma of collective action: Why academic journals cost too much. College & Research Libraries, 78(2), 183-200. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.2.16581

Willinsky, J. (2006). The access principle: The case for open access to research and scholarship. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Retrieved from https://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/handle/10150/10652

I had so much fun breaking myself into tiny pieces the first time around, I’ve decided to revise and expand RTEL into a 2nd edition that will be available in 2019. While much of the foundational content of the 2011 version (e.g., instructional design) is sill relevant/solid, many parts are temporally and experientially outdated.

Specific technologies referenced have reached the point of near-irrelevance, but more pressingly I wrote from a personal narrative perspective that represented my experiences in the jobs I’d held to date at Ohio University and UC Berkeley. The first edition therefore leaves out years of productive experimentation by myself and my colleagues at the Claremont Colleges, perspectives I’ve gained as an ACRL Immersion faculty member and administrator at CSUSM, and a lot of consciousness-raising and pedagogical/theoretical grounding that I simply did not possess due to gaps in my own early knowledge base. This accumulation of experience gives me an opportunity to address and expand essential components that received short shrift the first time around, such as critical/feminist pedagogy, program/project planning, and many more facets of learning assessment and technology.

When you write something, you (hopefully) want it to be of a) use and b) quality – this book is used as a course text in a fair number of IL-focused LIS classes, so I also figure it’s in our collective best interest to not mess around. To revise RTEL in alignment with these principles, I’m asking for libraryland’s brainpower in two ways:

1) If you’ve ever read some or all of RTEL and want to communicate your impressions/critiques/suggestions to help inform the 2nd edition, please do so via this survey (also embedded below). It should take 10 minutes or less:

2) Whether you’ve read the book or not, please share your insights into how you were (or weren’t) trained to be a teaching librarian. This one is a bit longer, 15-20 mins max – survey available here and is embedded below:

Participating in these by March 1st would be hugely useful. By way of incentive, if you complete one or both of the surveys send your email address to charbooth at gmail dot com to let me know. For each completed survey you’ll be entered into a drawing for one of 10 preorder copies of the new edition, paper or digital (emailing me directly helps preserve anonymity of responses).

In sum: thanks a million for helping me practice what I preach, and I’m looking forward to integrating your ideas into RTEL redux – your time/energy/wisdom are much appreciated, as always.

]]>allyship, community, and tools for change: social justice summit keynote transcript (part 3 of 3). See the full slide deck here, and this part of the transcription begins at slide 69.

Char: “Now I want to talk about a few things that are meaningful in the way that I work with my colleagues at CSUSM in terms of this idea of seeing the flaws in the system. Seeing the cracks inside of the people in our community, and doing the work that we can in our jobs to help address those problems and make social change out of those hurts and those flaws.

I already said that my job is to keep the building from catching fire and make sure that everyone gets a paycheck. But the more important part of it is for me to constantly interrogate myself about what values are most essential to our communities at CSUSM – among you – and ask what can allyship do to inform and inspire our Library and the way that it works and the programs that it creates. I see Josh Foronda (Student at Large Representative for Diversity & Inclusion, Associated Students Inc.) nodding over there, we’ve been though this conversation together on an accessible tech project. That’s good.

A couple of years ago we had this photography exhibit up in the Library lobby called the (in)visible project, I don’t know if y’all remember this, it was portraits of homeless people in San Diego, big beautiful black-and-white photographs by Bear Guerra, humanizing homeless subjects [nods around the room]. We had a panel associated with the exhibit and Prof. Jill Weigt was on it, and she had been doing these activities about food and general resource insecurity among her CSUSM students. She had an extra credit exercise where she asked students to answer the question, “What are the three barriers to your academic success?”

Over and over and over again what she ended up hearing was “due to my employment situation I can’t always make it to class,” “I’m in poverty,” “I have food insecurity,” I don’t have anywhere to live,” I’m on parole, I just got it out of prison.” This person summed it up best of all – “my culture, my economic background, and my race.” A library’s job is to help people gain access and empowerment and be successful in spite of these things. What we do at our library, and I hope I have something to do with this, is constantly look for the ways we can help people deal with those barriers and find themselves represented in our building.

A library’s job is to help people gain access and empowerment and be successful in spite of these things. What we do at our library, and I hope I have something to do with this, is constantly look for the ways we can help people deal with those barriers and find themselves represented in our building.

Something that my administrative privilege allowed me to make happen on campus speaks directly to this. When I started out at our Library there was only one way to give students employees a raise: if they’d worked 500 hours, and this was a campus-wide rule. I was like, “no, absolutely not” because the minimum wage in California was fixing to start going up [1], so people who were making $10.50 an hour who had worked for us for a while but not quite that long were all of a sudden going to be making the same amount of money as those who were just hired. That’s not fair, that’s not equitable. So I went to HR and said “do you know there’s this problem with student employee wages where you can only give people raises if they’ve worked a million hours?” and then explained the challenge with the equity raises.

Something that my administrative privilege allowed me to make happen on campus speaks directly to this. When I started out at our Library there was only one way to give students employees a raise: if they’d worked 500 hours, and this was a campus-wide rule. I was like, “no, absolutely not” because the minimum wage in California was fixing to start going up [1], so people who were making $10.50 an hour who had worked for us for a while but not quite that long were all of a sudden going to be making the same amount of money as those who were just hired. That’s not fair, that’s not equitable. So I went to HR and said “do you know there’s this problem with student employee wages where you can only give people raises if they’ve worked a million hours?” and then explained the challenge with the equity raises.

They said “ah yes, that’s a thing” and went off and discussed it and actually changed the rules – raises and starting salaries [for student employees] can now be based on equity, job complexity, prior experience, and other factors beyond accumulation of hours. Which was a big change, and which I was so thankful for. What it took was me hammering away at them – politely, mind you – for months to keep the issue on the radar and make the case that we needed the rules change to be able to do what was right.

Each year when the new wage kicks in we give all Library students not affected directly by the wage increase an equity bump to keep things fair and balanced. We wanted to analyze this annually to make sure it was correct. And so the only way we were going to have a progressive, equitable wage strategy as the minimum wage increased was if we got campus to change the rules. It’s probably my proudest achievement in this job – why was it that way? I knew it could change, I stuck with it, and they changed it. So, anyway, you can ask for a raise in your campus jobs now… you can ask. Word to the wise. [Participants and facilitators hollering and pointing at Floyd Lai, Cross-Cultural Center Director, followed by laughter].

Another thing we do is around textbook affordability. A few semesters ago my colleague Carmen Mitchell got inspiration from the #textbookbroke project and set up an activity where we put up bulletin boards in the front of the library and asked students what they could afford if they didn’t have to buy textbooks. We got hundreds of notes and the ones that were legit were really telling – “I could get a life”, “I could buy some food,” “I could get a parking pass,” “I could fix my teeth.”

Textbooks cost thousands and thousands of dollars – you know this. What’s the Library going to do about it? We’re going to do something about it. This is a huge challenge to success at CSUSM, and our institution has the ability to flip that on its head and say “here are your textbooks for free.” That’s what we’re trying to do, and it’s about economic justice. Check if your textbook is on reserve at the checkout desk in Kellogg – each semester we’re systematically renting textbooks for the 50 highest-enrollment classes as well as the most expensive textbooks assigned, and you can check them out for free, two hours at a time. There’s a great chance we’ll have your books for at least one class if not more. When we focus on the economic insecurity of our learning population, like with the the Cougars Affordable Learning Materials (CALM) program, we also work with professors to make your readings free. We’re working on another where people can donate their old textbooks to the Library and we’ll have a textbook swap. In the future there will be a chance to go up to a row of donated textbooks in the Library and pull the ones you need for free.

A couple other things that I’m super stoked we’re doing when we focus on economic insecurity: we don’t charge late fees anymore. I think late fees are messed up… so, why are we going to penalize you for checking out a book? It’s counterintuitive and doesn’t support the economic justice mission of our university. If you’re having challenges getting through school because of funds, it’s like salt in a wound to charge you a late fee for having a book checked out. Now the only thing we charge for is reserve books, which are high demand, and lost items, which we have to do because it’s our bottom line. Also, working with Associated Students, Inc. (ASI) – totally funded by students by the way – to make sure we’re open 24 hours Sunday through Thursday. [Sustained snaps and applause.] This is a project I’ve led and I’m super proud of it. It’s going so well, so many people are using this space. [Audible agreement from participants and facilitators.] We’re also working with ASI to get free food from the Cougar Pantry to put out overnight, and we have a hot kettle and microwave – this is the stuff that brings me joy. To be able to say, “come on in, it’s a safe place to study, access to the Academic Success Center, seven study rooms, a huge computer lab, it’s amazing.”

Just removing barriers. Do you see where I’m coming from? [Audible agreement from participants and facilitators.] Allyship in work is removing barriers. Stupid barriers that don’t need to exist that people just didn’t even realize were there because they didn’t see it with the right perspective or the perspective that came from having been challenged in that way.

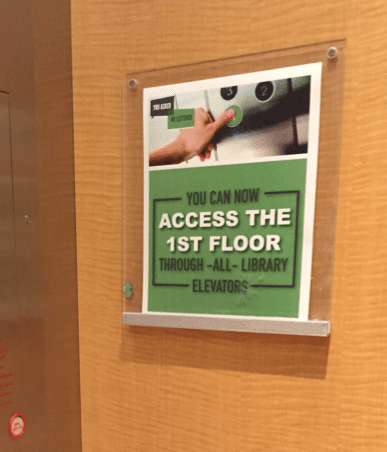

Here’s a perfect example. When I got to the Library in 2015 people couldn’t take the elevator down to the first floor of the library building from the upper floors. You know, the first floor where there were three campus classrooms and like five learning and tutoring centers. This is now a fading and distant memory, but at my job interview I was like “this is challenge number one for me when I get hired, this is not going to happen anymore, this is awful and we’re going to fix this.” Originally I think the decision was made to restrict elevator access to the first floor out of concern for lost materials, but the argument I and my colleagues tried to make is that a few lost items is the cost of doing business and less important than ease of access. People need to be able to get from the 5th floor to their classrooms and centers on the 1st floor without going outside and walking around to the outside elevator or stairs. What about people who use mobility assistance? How are we treating them? We’re displacing them. So that’s fixed now and people can go straight down to 1 without any drama of being kicked out of the building on the way. That was a big one, and a big win, for me.

So this principle of simply recognizing barriers, removing barriers. Recognizing problems, fixing problems. Problems are not always going to be fixable, but if you don’t try nothing’s going to happen. This is solidarity, this is allyship in work. Same goes with the physical accessibility of our building – it’s not good enough yet, and I’m working on it, and it’s going to get better. I’m working on it in conjunction with something like eight departments across the University. You have to be able to create these big networks of different stakeholders – Facilities, Planning Design & Construction, Human Resources, Disabled Student Services, Title 9. It’s a big undertaking. But again, if you don’t figure out how to find those cracks and paint gold on those cracks and say “this is a problem and we need to fix it,” then it’s not going to happen.

So that’s allyship. It’s about seeing those barriers and taking the time and the energy to make it your job – your actual job – to fix those things. I already mentioned the Context Library series – we have a mission and a dedication in our library to make sure that justice movements are represented and that students of color see themselves in our lobby when they walk in. We organize panels that are amazingly political. Most libraries would be afraid to do things like this. We sponsor the Common Read every year, and without fail the Common Read is voted to be an amazing book. This year Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, last year Sal Si Puedes by Peter Matthiessen. They’re always incredible. Doing this work to lead the community in this conversation around common justice-oriented ideas and narratives. We don’t have to do this work but we do because it’s right and it’s important.

Some other things are underway that you can’t see yet but hopefully you’ll see someday. I’m trying to get some murals painted in the Library, some big beautiful permanent murals to honor the incredible spirit of Chicano Park and the art that’s come out of this county [snaps and applause]. We’re working with a couple of very talented artists on this proposal. Getting public art done is always challenging, but we’re working on it and I hope will be successful. We have to convince people that the risk of this amazingness is worth it. Another friend, and please look her work up – Jessica Sabogal, she’s visionary muralist who has different campaigns, one’s called “Women are Perfect” and another “White Supremacy is Killing Me” – she makes these massive outdoor murals, beautiful representations of women of color in struggle. And that’s what I want in our library and I’m working to make it happen. We’re looking at different spaces in our building, we’re identifying artists who are inspiring, and we’re working through the system to try and get this done.

This is my attempt to say that you can’t always see the work in progress, or the effect, or the outcome. And some things crash and burn, you know, but they’re still worth trying even though they’re frustrating. [Comment from Ariel Stevenson, CSUSM Diversity Coordinator: “And we keep trying anyway.”] And that’s right, we keep trying anyway. Because that’s the hard work, and that’s the love we bring to the hard work from our places of pain and other people’s places of pain. Recognizing them, seeing their barriers, seeing the cracks and the pain that makes them beautiful, and doing what we can to rectify that and to represent the people who are marginalized and oppressed.

Okay. I’m going to leave y’all with a couple of lil’ thoughts, lil’ insights that I feel like I wanted to encapsulate about what being a working ally looks like. And I want to bring us back to this politics of imperfection and responsibility. You see imperfection and it’s your responsibility to do something about it. We’re all imperfect, and it’s our responsibility to work on our own imperfections and educate ourselves and become better allies.

And I think in one’s life you have to focus on what you can affect. Focus on what you can change. If you go too far up and too far out the weight of it becomes crushing. You cannot fix everything, but you can see things in your environment that can get better. You can overhear an interaction, or someone says something offensive, and you can step in and help that person learn how not to do that again. With grace. With grace. Because that’s when things work.

Sing each others’ praises. You’re amazing, let each other know. Identify those amazing members of your communities that are doing good work and doing beautiful work and signal boost them. Help their names get out there, help people know about who they are because that helps them be more successful and have greater impact. Name dropping is the funnest thing in the world – do it.

Here’s one that’s hard. It’s the hardest one of all. Try to humanize your antagonists. Like I said, when I was young and being subject to a lot of violence I tried to understand why it was happening. This is not something you have to or should do if it’s not safe, but you can try to do it if it’s safe for you to do so. There’s a podcast I wanted to mention called Conversations with People Who Hate Me, it’s by this person Dylan Marron, who is a media activist and has other series like Unboxing where he physically unpacks things like white supremacy culture. This podcast is so fascinating, he finds people who have doxxed him online, or given him abuse in social media – I don’t even want to go into what they say – but he’ll identify the people and have long consensual recorded conversations with them about why they said the things they did and do they really hate them and what’s their background. I swear, if there’s anything you listen to this year let it be this. It humanizes these people who have hurt him, it shows you that each and every one of them has pain of their own that’s creating this aggression toward other groups. Invariably these conversations are peaceful and generative. They come to a place of greater understanding.

Finally y’all, believe in resilience. We all have it – we’re all suffused with it. And if you’re in this room, you have more than most people. [Facilitator applause.] Resilience is what lets you continue to be an ally even when it’s hard, even when stuff doesn’t work out. To work in community and believe in the resilience of that community even when it’s under assault, because let’s face it: our communities are under assault and we have to be resilient with one another. And lean on each other and celebrate each other. And try to see what’s behind that antagonism that’s coming at us.

That was my presentation. [Appaluse.]

Question from Diversity Coordinator Ariel Stevenson: So who wants to be a librarian?

Answer from Char: That was my secret mission, to convert all of you. We recruit!

Comment from Floyd Lai: We have a few minutes, I think one of the benefits of inviting faculty from campus to come is for you all to get to know some of the folks that are working and doing amazing work. I appreciate the connection, because now when you walk into the library you might have a very different perspective on what’s happening there. We have about 5-7 minutes if you want to ask questions of Char.

Question: What was that image of the shirt and the heart?

Answer: Ah yes, that’s an image I use in presentations to represent that I wear my heart on my sleeve and work hard. I really do love the work that I do and you have to put your heart into your work or you become a zombie. The day in and day out of administrative work can be challenging, but if you keep focused on that love and that good outcome then it motivates you to continue doing the important stuff and the good stuff, like 24 hour access and helping to solve food insecurity on campus.

Question: You said that there are gender neutral bathrooms now in the Library? Where are they?

Answer: If you’re in the elevator lobby by the Context exhibit space on the 3rd floor, you’ll see a sign that says “gender inclusive restrooms” pointed at a hallway and in that hallway there are three of them. We’re also working with different offices on campus to construct two new gender inclusive restrooms on the 2nd floor as well, because the one thing that the 24/5 space doesn’t have yet is a gender inclusive restroom and that’s not acceptable to me. That’ll happen hopefully by the beginning of next year.

Question: I have a comment about the exhibits, they’re amazing and I loved the one about banned books. Whoever is doing that is awesome.

Answer: Thank you, I’ll pass that along.

Same student: Also, the staplers in the copy rooms are always empty. [Laughter.]

Answer: You’re breaking my heart with that, you know? [Laughter.] It’s literally my job to fix that and I will, I promise. [Note – I’ve since increased student assistant stapler filling from every other day to daily].

Question: You probably already answered this but, every morning when you wake up what is your drive to continue? I know that you want to make sure that there is a change, but some days it’s just like “what the hell, I’m exhausted and I’ve ben fighting these people for months now and they’re still not doing it.” What’s that spark that keeps you going and looking for that light in a dark room.

Answer: That’s such a great question. I give it space. If I have a hard situation or I get a bummer answer to something I’ve been working on, I’m going to let that situation sit there for a couple of days until my spirit heals, and in the interim I’m going to take care of myself, something I can get done, like fill the staplers or something. [Laughter]. You’ve got to give yourself breaks as you’re hammering on this stuff. Take care: rest, rejuvenate, go back to the fight. Rest, rejuvenate, go back to the fight. And I just know that this is all the right thing to do – I would be ashamed of myself if I just let these problems sit there and persist. It is my responsibility and it’s very clear to me. I can’t fix everything, no one can fix everything, that’s grandiosity and it doesn’t work. But if you see a problem, work on the problem. There’s a lot of problems – see it, work on it, figure out how to work on it.

Question: How do you – you mentioned some things about your whiteness – how did you navigate in between those spaces of activism, and knowing when to step up when to step back and when to give space. How did you navigate between those different processes and maybe even pushback from others?

Answer: It’s such a hard question and such a good question. I am quiet and I listen and I learn. I don’t know if this is an intuitive thing or a learned thing, but I know when to keep my mouth shut and I know when to be really loud. I know that I will make mistakes in communities that I am not of. I know that others who are not of my communities will also make mistakes. I have solidarity in that experience of messing up badly. I am willing to have that incredibly discomfiting experience of being taught and being told that I need to learn. For me, in my workplace is where I step up loud and hard and get this stuff done because that is the space that I inhabit on my day-to-day, and I’m in a group of colleagues who are focused on a similar mission. And because I have class and race and positional privilege in that it’s my time to step up and advocate for others. When I’m in other activist spaces, spaces that are predominately POC working on issues that affect POC, I’m much more quiet and I hang back and I don’t jump out and try to say “I’m queer I’m trans, look at me” – there’s no need for me to throw out my oppression credibility every time I’m in an activist space. I did that here because I was asked to, because I needed to. So I try and I think other white folks should try and navigate with grace and humility and care and an utter sharp awareness of what you have, who you are, what you’re comprised ,of and how it affects other people, even without you intending it to. It’s like a sensitivity, a dial. Like a literal environmental sensitivity. I think that social justice activism helps you develop a sensitivity to these dynamics, knowing when to be quiet, go home, read up, and not constantly be asking the people are impacted to tell you what’s up.

Okay, it’s time. Y’all are so awesome, thank you so much.”

This was part 3 of a three-installment series. If you’re just realizing this, go back and read parts 1 and 2.

—

[1] California’s minimum wage is increasing incrementally each January to a living wage threshold of $15 in 2023. Which is a very good thing, and I’ll write about student assistant employment practices/wage justice in a future post.

—

Postscript: I have a new website at charbooth.com for updated presentation, publication, cv etc. content but will keep info-mational active for blog type things.

]]>You can see the full slide deck here, and this transcript begins at slide 23.

allyship, community, and tools for change: social justice summit keynote transcript (part 2 of 3).

Char: “So, I work in Kellogg Library as an administrator. Social change and social justice are not actually in my job description. So I have to put them in there, I have to make these things part of my day-to-day work and justify my rationale for doing so to the benefit of the institution. My job, in its simplest form, is to make sure people are paid and that our building doesn’t fall over [laughter]. There’s some other stuff in there too, like, being on committees. So I could just do that and we’d have people with paychecks, a library that’s standing, and way less awesome things happening on my watch. I would still get paid the same amount of money, but I’d have no self-respect because I wasn’t using my position to make things better in the world and in my community.

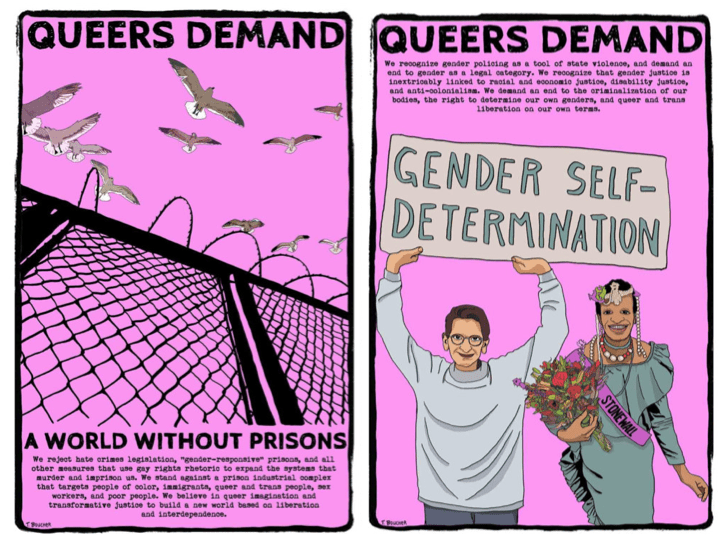

One of the things that I’ve managed to do as an activist administrator is to try and improve the visibility of resources for trans and gender non-conforming people on this campus. Here’s another person I want to call out in my community orbit who does incredibly important art and design work as an activist – Micah Bazant, who created this graphic and is one of the founders of the Trans Life and Liberation Art Series.

When I got to our Library a couple of years ago I noticed that we have three awesome single stall de facto all-gender restrooms on the third floor that just said “restroom” on them. Then I noticed that the door leading back to the restrooms was always closed and locked. And I asked “why is this like this?” “Oh, anyone can use those but they just can’t find them so no worries.” To me, that’s completely unacceptable. So instantly, it’s my job to figure out how to fix that. To get that hallway door unlocked and propped open, get those restrooms labeled as gender inclusive, and raise awareness in the community that they exist.

So I begin to figure out the different levers I had to pull to make that happen. What activism on the ground in an administrative job often looks like is being able to deal with the minutiae that it takes to make that happen. There’s so many different rules and regulations and groups and people you have to convince and costs you have to pay but if you just keep at it it happens… eventually. Not always, granted, but you can make it happen. So seeing that as a need our organization was not being a good enough ally to trans and GNC people – I saw that because I’m one of them, I didn’t have to be one of them to see it, but I saw it, and I fixed it, and that is a good thing. And every day I try to see something like that and fix it and keep moving toward that goal.

So I begin to figure out the different levers I had to pull to make that happen. What activism on the ground in an administrative job often looks like is being able to deal with the minutiae that it takes to make that happen. There’s so many different rules and regulations and groups and people you have to convince and costs you have to pay but if you just keep at it it happens… eventually. Not always, granted, but you can make it happen. So seeing that as a need our organization was not being a good enough ally to trans and GNC people – I saw that because I’m one of them, I didn’t have to be one of them to see it, but I saw it, and I fixed it, and that is a good thing. And every day I try to see something like that and fix it and keep moving toward that goal.

Partly because of this effort I was asked to Chair a campus-wide Trans and Gender Non-Conforming Task Force this last winter. This was an intensive process – we were given about four months to do this herculean task of reviewing the university’s resources and how we can make them better for trans people. Instead of doing your normal, typical “we could improve the bathrooms a bit” or “make that name change thing a little easier” we went for it and tried to encourage the university to comprehensively address all of these issues. I know as a realist that it’s not all going to happen. When these things are implemented, not all the recommendations in our report will be done, but enough of them will be done to have actually achieved change. And while it’s hard as a trans person to be asked to do that work, to be asked to highlight the flaws and the ways you’re oppressed and how your institution could fix that oppression – in this case, I wanted to be the one doing that. Because another administrator who didn’t have the same experience might not know as well where to look for issues and solutions. In that case I felt responsible for being that ally, and recognizing that my position of privilege in the university allowed me to effectively advocate for people like me.

And so that’s one of those moments where I accepted the fact that looking through all these statistics about how much more trans women of color die than everyone else, literally crying as I’m writing this report, that I can take on because I think it will do something. It hurt me, it made me lose sleep, it made me feel pretty awful for a couple of months. But that’s alright with me this time, I made that choice because of my power and positionality in the university. I knew that delegated to someone else, perhaps I and the committee couldn’t have covered the same ground, or that some direct perspective could have been lost. When you’re confronted with the challenge of doing social justice work in the world, of doing this activism which you are obviously willing to do, you have to make calculations about what you can take on and the pain that you’re willing to endure to be responsible for making that change. And it’s not always going to be something you want to take on. And that’s okay.

I’m going to shift gears a little bit and talk about my past. Up til now has been my current story, but I want to go back some years and think about those early cracks, those early hurts that happened in my life and how I’m trying to turn and twist them around. And how I’ve survived that and learned from it and learned to take it forward.

I’ve lived all over the country for what feels like a million different jobs, but I mentioned that I come from Texas (and very much so). Long line of Anglos in Texas: teachers, preachers, and capitalists, basically. I also come from an incredibly rigid gender binary. So that’s my momma – she’s amazing – but that image is the embodiment of the culture I was raised in. Debutante city.

My first conscious memory as a child was realizing that I wasn’t a boy – it’s so vivid in my mind. From that point on, I was about four years old, I never fit this binary mold. I knew that I was different, I knew I was trans. By the time I was twelve I also came out as queer in this small bible belt town, and I endured a ferocious amount of persecution and violence. I was just that kid, I was that one kid that got attacked in that way. I never turned away from my identity, I never backed down from it, and I have the scars to prove it. Those years were so incredibly difficult for me. I managed to get out by the time I was seventeen. I had a couple of teachers that helped me graduate early from high school – kind of like, “you’re going to die, and we’re going to help you so you don’t have to.” This was an incredible privilege. I don’t know why these people did this for me, but they saw me struggling and touched me and said we’re going to work with you on this. Otherwise… [shrugs].

One of the things that I was able to realize throughout all of that torture is that the people who were perpetrating this violence against me were themselves struggling, were themselves victims of poverty and oppression. There is no oppressor without their own story, no antagonist without their own pain. So even at this young age I realized that “I’m a target, but these people are also targeted.” It’s a cycle that goes down, a cycle of oppression.