| CARVIEW |

Igor Pak's blog

On faith, religion, conjectures and Schubert calculus

Just in time for the holidays, Colleen Robichaux and I wrote this paper on positivity of Schubert coefficients. This paper is unlike any other paper I had written, both in the content and the way we obtained the results. To me, writing it was a religious experience. No, no, the paper is still mathematical, it’s just, uhm, different. Read this post till the end to find out how, or go straight to the paper (or perhaps both!)

Faith, religion and miracles — math got them all!

Mathematicians rarely if ever discuss the subject. When they do, they get either apologetic about it “there are no contradictions…”, or completely detached as if you can be deeply religious on Sunday morning and completely secular on Tuesday afternoon. See e.g. Robert Aumann’s extensive interview or this short clip by Freeman Dyson, two of the most admired people in their respective fields.

I have neither a religious education nor a specialized knowledge to speak on the subject, obviously. But in the age of Twitter (uhm, X.com, sorry) that minor issue never stopped anyone. So having said that, let me give a very vague and far-fetching primer to mathematicians in the language you could relate. This might prove helpful later on.

Faith is the foundation of it all. You really can’t do math without foundations. Outside of certain areas you don’t really need to understand it or even think about it all that that much. Just accept it and you’ll better off. For example, it is likely that the more you think about consistency of PA the less certain you get about what you are doing, so stay on the happy side.

This does not mean you need to be consistent with your owb tenants of faith. For example, it’s perfectly fine to have a paper in algebra using the Axiom of Choice (AC) while in another in descriptive set theory, where you go out of your way to avoid AC, and that’s the whole point of the paper. Still, it’s not like you were ever doubting AC — more like you have a multifaith personality.

Belief system is what it sounds like. If you are a working mathematician you probably already have a lot of opinions on a wide range of research questions, conjectures, etc. For example, maybe you accept some conjectures like Riemann Hypothesis, reject others like Navier-Stokes, remain very interested but undecided on problems like P vs. NP, and couldn’t care less about others like Yang-Mills. It’s all well and good, obviously.

There are many more shades of gray here. For example, you might believe in the abc conjecture, think that it hasn’t been proved yet, but willing to use it to prove other results whatever the status. Or perhaps, you believe that Goldbach’s conjecture is definitely true, that it’s a matter of time until it’s proved, but are completely unwilling to use it as an assumption (I used it as an assumption once, maddening some old school referees; luckily the odd version of GC holds and was sufficient). Or perhaps you are aware that the original proof of the Lyusternik-Schnirelmann theorem on three closed geodesics had major issues, as were many subsequent proofs of the theorem; still you are willing to trust Wikipedia that the theorem is true because you don’t care all that much anyway.

Ideally, you should question your beliefs whenever possible. If you are thinking about a conjecture, are you sure you believe in it? Maybe you should try to disprove it instead? It’s ok to change your mind, to try both directions, to believe or even to disbelieve all authorities on the matter. I have written extensively about the issue in this blog post, so let’s not rehash it.

One more thing about a belief system is that different beliefs usually have different levels of confidence. Some beliefs are core and people rarely change their mind. These don’t fall into faith category, in a sense that different people can have different core beliefs, sometimes in contradiction with each other. This is usually why a vast majority might strongly believe some conjecture is true, while a vocal minority might believe it’s false just as strongly.

For example, some people believe that mathematical order is absolutely fundamental, and tend to believe that various structures bring such an order. My core belief is sort of the opposite — because of whatever childhood trauma I experienced, I believe in universality theorems (sometimes phrased as Murphy’s law), that things can be wildly complicated to the extreme unless there is a good reason for them not to. Mnëv’s universality theorem is perhaps the most famous example, but there are many many others. This is why I disprove conjectures often enough and prove many NP– and #P-completeness results — these are different manifestations of the same phenomenon.

Religion is what you do with your belief system, as in practicing religion. If you have a lot of beliefs that doesn’t make you smart. That makes you opinionated. To be considered smart you need to act on your beliefs and actually prove something. To be considered wise you need the ability to learn to adjust your belief system to avoid contradictions with your other beliefs as new evidence emerges, and make choices that lead somewhere useful.

In mathematics, to practice an organized religion is to be professional, when you get paid for doing research. The process is fundamentally communal involving many people playing different roles (cf. this Thurston’s MO answer). Beside the obvious — researcher, editor, referee, publisher — there are many others. These include colleagues inviting you to give talks, departmental committees promoting you based on letter written by your letter writers. Some graduate students will be studying and giving talks on your work, others will be trying to simplify the arguments and extend them further. The list goes on.

In summary, it is absolutely ok to be an amateur and have your own religious practice. But within a community of like-minded scholars is where your research becomes truly valuable.

Miracles are the most delightful things that ever happen to you when learning or when doing mathematical research. It’s when you discover somethings, perhaps even prove that it works, but remain mystified as to why? What exactly is going on that made this miracle happen? Over time, you might learn one or several reasons, giving you a good explanation after the fact. But you have to remember your first impression when you just learned about the miracle.

It’s even harder to see and acknowledge miracles in celebrated textbook results. You have to train yourself to see the miracles for what they are, rather than for what they now appear to be when textbook packages them in neat nice boxes with a bow on top. One way to remind yourself of miracle powers is to read “Yes, Virginia“ column that I mentioned in this holiday post — it will melt you heart! Another way is to teach your favorites — when you see a joyful surprise in your students’ eyes, you know you just conveyed a miracle!

This may depend on your specific area, but in bijective combinatorics you have to believe in miracles! Otherwise you can never fully appreciate prior work, and can never let yourself loose enough to discover new miracles. To give just one example, the RSK correspondence is definitely on everyone’s the top ten list of miracles in the area. By now there are at least half a dozen ways to understand and explain it, but I still consider RSK to be a miracle.

Of course, one should not get overexcited about every miracle they see and learn to look deeper. For example, a combinatorial interpretation of Littlewood–Richardson coefficients is definitely a miracle, no doubt about it. But after some meditation you may realize that it’s really the same miracle as RSK (see §11.4 in my OPAC survey).

Backstory of the bunkbed conjecture paper

After I wrote this blog post about our disproof of the Bunkbed Conjecture (BBC), the paper became viral for 15 minutes. Soon after, I received several emails and phone calls from journalists (see links in the P.P.S. of that post). They followed the links to my earlier blog post about disproofs of conjectures and asked me questions like “What is the next conjecture do you plan to disprove?” and “Do you think disproving conjectures is more important than proving them?” Ugh… 😒

While that earlier post was written in a contrarian style, that was largely for entertainment purposes, and not how I actually think about math. Rather, I have an extensive somewhat idiosyncratic belief system that sometimes leads me think that certain conjectures are false. But breaking with conventional wisdom is a long and occasionally painful process. Worse, being a contrarian gives you a bad rap as you are often get confused with being nihilistic.

So let me describe how I came to believe that BBC is false. I was asked this multiple times, always declining out of fear of being misunderstood and misquoted. but it’s a story worth telling.

This all started with my long FOCS paper (joint with Christian Ikenmeyer), where we systematically studied polynomial inequalities and developed a rather advanced technology to resolve questions like “which of these can be proved combinatorially by a direct injection?” To give a basic example, if the defect (difference between two sides) is a polynomial that is an exact square, then the polynomial is obviously nonnegative but it often can be shown that the defect has no combinatorial interpretation, i.e. not in #P. See more in this blog post on this.

Now, I first learned about the Bunkbed Conjecture soon after coming to UCLA about 15 years ago. Tom Liggett who was incredibly kind to me, mentioned it several times over the years, always remarking that I am “the right person” to prove it. Unfortunately, Tom died just four years ago, and I keep wondering what he would have made of the story…

Anyway, when writing my OPAC survey two years ago, I was thinking about the problem again in connection to combinatorial interpretations, since BBC becomes a polynomial inequality when all edge probabilities are independent variables. Like everyone else, I assumed that BBC is true. But I figured that the counting version is not in #P since otherwise a combinatorial proof would have been found already (since many strong people have tried). So I made this into Conjecture 5.5 in the OPAC paper, and suggested it to my PhD student Nikita Gladkov.

I believed at that time that there must be a relatively small graph on which the BBC defect will be a square of some polynomial, or at least some positive polynomial (on a [0,1]n hypercube of n variables) with negative coefficients. That was our experience in the FOCS paper. Unfortunately, this guess was wrong. In our numerous experiments, the polynomials in the defect seemed to have positive coefficients without an obvious pattern. It was clear that having a direct injective proof would have been a miracle, the kind of miracle that one shouldn’t expect in the generality of all graphs.

This led to a belief contradiction — either a stronger version of BBC holds for a noncombinatorial reason, or BBC is false. In the language above, I had a core belief in the power of combinatorial injections when there are no clear obstructions. On the other hand, I had only a vague intuition that BBC should hold because it’s the most natural thing and because if true it would bring a bit of order to the universe. So I changed my mind about BBC and we started looking for a counterexample.

Over the next two years I asked about BBC to everyone I met, suggesting that it might be false in hope someone, anyone, gives a hint on how to proceed and what to rule out. Among those who knew and had an opinion about the problem, everyone was sure it’s true. Except for Jeff Kahn who lowered his voice and very quietly told me that he also thinks it’s false, but made me a promise not to tell anyone (I hope it’s ok now?) I think he was hinting I shouldn’t say these things out loud to avoid getting the crank reputation. I didn’t listen, obviously. Not being in the area helped — nobody took me seriously anyway.

In the meantime, Nikita and his friend Alexander Zimin made quite a bit of effort to understand multiple correlation inequalities (FKG style) for percolation on general graphs. This eventually led to the disproof as explained in the BBC blog post mentioned above.

Schubert positivity

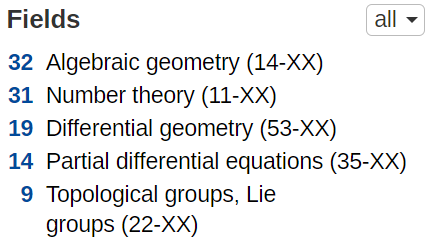

In Algebraic Combinatorics, Schubert coefficients are nonnegative integers which generalize the Littlewood-Richardson (LR) coefficients mentioned above. Since the latter have extremely well studied combinatorial interpretations, the early hope was that Schubert coefficients would also have one. After decades of effort and advances in a handful of special cases, this became a major open problem in the area, the subject of numerous talks and papers.

I never believed this hope, not for a second. In the OPAC survey, I stated this as a conjecture: “Schubert coefficients are not in #P” (see Conj. 10.1). Again, this not because I was a contrarian — I had my reasons, three in fact.

First, that’s because I studied the miracle of RSK and the related miracle of LR-coefficients for over thirty years (yes, I am that old!) As a bijection, RSK is extremely rigid. So if any of the (essentially equivalent) combinatorial interpretations of LR-coefficients could generalize directly, it would have been done already. However, the progress has been exceedingly difficult (see e.g. Knutson’s 2022 ICM paper).

Second, I also have a strong belief that miracles are rare and don’t happen to the same combinatorial objects twice for different reasons. This is a variation on “lightening doesn’t strike twice” idea. It is in principle possible that LR-coefficients have a completely new combinatorial interpretation radically different from the 20+ combinatorial interpretations (see OPAC survey, §11.4), all of them related by relatively easy bijections. But I had my doubts.

Third, I knew quite a bit about efforts to find a combinatorial interpretation for Kronecker coefficients which also generalize LR-coefficients in a different direction. Joint with Greta Panova, I have written extensively on the subject. I was (still am) completely confident that Kronecker coefficients are not in #P for many reasons too long to list (this is Conjecture 9.1 in my OPAC survey). So I simply assumed that Schubert coefficients are also not in #P, by analogy.

Having concluded that one should work in the negative direction, Colleen and I made a major effort towards proving that Schubert coefficients are not in #P, aiming to emulate the strategy in my paper with Chan, and in earlier work with Ikenmeyer and Panova. The basic idea is to show that the positivity problem is not in the polynomial hierarchy PH, which would imply that the counting problem is not in #P. We failed but in a surprisingly powerful way which led me to rethink my whole belief system when it comes to Schubert calculus.

By the Schubert positivity problem we mean the decision problem that Schubert coefficients are positive. This problem is a stepping stone towards finding a combinatorial interpretation, and is also of independent interest. In our previous paper with Colleen, we proved that the positivity problem is in the complexity class AM assuming the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis (GRH). This is a class that is sandwiched between first and second level of the polynomial hierarchy, so in particular in contains NP and BPP, and is contained in Π2. In particular, my dream of proving that the positivity problem is not in PH was doomed from the start (assuming PH does not collapse).

Now that that Schubert positivity is in PH this explains the earlier failures, but leaves many questions. First, should we believe that Schubert coefficients are in #P? That would imply that Schubert positivity is in NP, a result we don’t have. Second, where did we go wrong? Which of my beliefs were mistaken, and what does that say about the rest of my belief system?

Let me start with the second which easier to answer. I continue to stand by our first belief (the miracle of RSK and LR) — this is going nowhere. I am no longer confident in the second belief. It is possible that #P is so much larger than traditional combinatorial interpretations that there is more to the story. And lightnings can strike twice if the buildings are especially tall…

More importantly, I now completely reject the third belief of analogy between Kronecker and Schubert coefficients. While the former is fundamentally representation-theoretic (RT), as our proof shows the latter is fundamentally algebro-geometric (AG). They have nothing in common except for the LR-coefficients. At the end, while we proved that Schubert positivity is in AM (assuming GRH) using the Hilbert’s Nullstellensatz, a key problem in AG.

Faced with a clash of core beliefs, Colleen and I needed to completely rethink the strategy and try to explain what do our results really mean? Turned out, my issues were deeper than I thought. At the time I completely lacked faith in derandomization, which is getting close to be a foundation belief in computational complexity, on par with P ≠ NP. I was even derisive about it in the P.S. to my BBC blog post.

On a personal level, saying that P = BPP is weird, or at least unintuitive. It contradicts everything I know about Monte Carlo methods used across the sciences. It undermines the whole Markov chain Monte Carlo technology I worked on in my PhD thesis and as a postdoc. I even remember a very public shouting match on the subject between the late Steven Rudich and my PhD advisor Persi Diaconis — it wasn’t pretty.

After talking to Avi Wigderson while at IAS, I decided to distance myself and think rationally rather than emotionally. Could P = BPP be really true? Unless you know much about derandomization, even P = ZPP seems unmotivated. But these conjectures have a very good reason in their favor.

Namely, the Impagliazzo–Wigderson’s theorem says that under a reasonable extension of the exponential time hypothesis (EHT), itself an advance extension of P ≠ NP, we have P = BPP. Roughly speaking, if hard NP problems are truly hard (require exponential size circuits), one can simulate binary strings by embedding meshed up solutions into the strings which then look random in a sense of poly-time algorithms can’t tell them apart. This is extremely vague and somewhat misleading — read up more on this in Vadhan’s monograph (Chapter 7).

There is also a CS Theory community based argument. In this 2019 poll conducted by Gasarch, there is near unanimous 98% belief that P = BPP by the “experts” (others people were close to even split). Given that P ≠ NP has 99% belief by the same experts, this crosses from speculation to the standard assumption territory. So it became clear that I should completely switch my core belief from P ≠ BPP to P = BPP.

And why not? I have blindly believed the Riemann Hypothesis (RH) for decades without any in-depth knowledge of analytic number theory beyond a standard course I took in college. I am generally aware of applications of RH across number theory and beyond, see quotes and links here, for example. From what I can tell, RH withstood all attempts to disprove it numerically (going back to Turing), and minor dissents (discussed here) do not look promising.

This all reminded me of a strange dialogue I had with Doron Zeilberger (DZ) over lunch back in October, when we went to celebrate the BBC disproof:

DZ: What conjectures do you believe? Do you believe that RH is true?

IP: I am not sure. Probably, but I don’t have enough intuition either way.

DZ: You are an idiot! It’s 100% true! Do you believe that P ≠ NP?

IP: Yes, I do.

DZ: Ok, you are not a complete idiot.

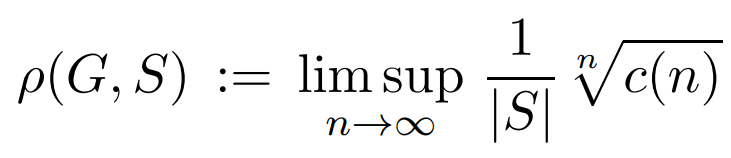

Anyway, back to the story. I figured that if you believe in RH you may as well believe in GRH. And if you believe in P ≠ NP you may as well believe in ETH. And if you believe in ETH you may as well believe in the Impagliazzo–Wigderson’s Assumption (IWA) which implies that P = BPP. And if you believe in IWA you may as well believe in the Miltersen–Vinodchandran Assumption (MVA) which is an interactive proof version of IWA introduced in this paper, and which implies that NP = AM. Once you break this it into steps, the logic of this implication becomes clear and the conclusion extremely believable.

Having thought through these implications, Colleen and I wrote this note which prompted this blog post. We aim at people in algebraic combinatorics and obtain the following:

Main Theorem [Robichaux–P.] Schubert positivity is in NP (i.e., has a positive rule) assuming GRH and MVA.

The theorem is the closest we got to proving that Schubert coefficients are in #P. The note is written in a somewhat unusual style, explaining the results and refuting potential critiques. Quotes by Poincaré and Voltaire are included in support of the case. Check it out!

In summary, the theorem above completely resolves the Schubert positivity problem albeit conditionally and from computational complexity point of view. It assumes two very hard conjectures, each stronger than a million dollar problem. But so what? It’s not even the first theorem which assumes two million dollars worth of conjectures (it’s a long article — search for “two million dollars”). And with inflation, one million in 2000 is about two millions now, so it’s probably ok to assume two such conjectures in one theorem anyway… 😉

Happy Holidays! Happy New Year! Best wishes everyone!

Concise functions and spanning trees

Is there anything new in Enumerative Combinatorics? Most experts would tell you about some interesting new theorems, beautiful bijections, advanced techniques, connections to other areas, etc. Most outsiders would simply scoff, as in “what can possibly be new about a simple act of counting?” In fact, if you ask traditional combinatorialists they would be happy to tell you they they like their area to be trend-resistant. They wouldn’t use these words, obviously, but rather say something about timeless, or beautiful art, or “balls in boxes”. The following quote is a classic of this genre:

Combinatorialists use recurrence, generating functions, and such transformations as the Vandermonde convolution; others, to my horror, use contour integrals, differential equations, and other resources of mathematical analysis. (J. Riordan, Combinatorial identities, 1968)

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, then you already know how I feel about such backward-looking views. When these win, the area becomes stale, isolated, and eventually ignored by both junior researchers and the “establishment” (leading math journals, granting agencies, etc.) Personally, I don’t I don’t see this happening in part due to the influence of Theoretical Computer Science (TCS) that I discussed back in 2012 in this blog post.

In fact, the influence of TCS is so great on all aspects of Combinatorics (and Mathematics in general), let me just list three ideas with the most impact on Enumerative Combinatorics:

- Thinking of a “closed formula” for a combinatorial counting function as algorithm for computing the function, leading to Analysis of Algorithms type analysis (see Wilf’s pioneer article and my ICM paper).

- The theory of #P-completeness (and related notions such as #P-hard, #EXP-complete, class GapP, etc.) explaining why various functions do not have closed formulas. This is now a core part of Computational Complexity (see e.g. Chapter 13 in this fun textbook).

- The idea that a “combinatorial interpretation” is simply a function in #P. This is my main direction these days, see this blog post, this length survey and this OPAC talk and this StanleyFest talk.

All three brought remarkable changes in the way the community understands counting problems. In my own case, this led to many interesting question resulting in dozens on papers. Last year, in the middle of a technical complexity theoretic argument, I learned of a yet another very general direction which seem to have been overlooked. I will discuss it briefly in this blog post.

Complete functions

Let A be a set of combinatorial objects with a natural parametrization: A = ∪ An. For example, these can be graphs on n vertices, posets on n elements, regions in the square grid with n squares, etc. Let f: A → N be a function counting objects associated with A. Such functions can be, for example, the number of 3-colorings or the number of perfect matchings of a graph, the number of order ideals or the number of linear extensions of a poset, the number of domino tilings of a region, etc.

We say that f is complete if f(A)=N. Similarly, f is almost complete if f(A) contains all sufficiently large integers. For example, the number of perfect matchings of a simple graph is complete as can be seen from the following nice construction:

Moreover, the number of domino tilings of a region in Z2 is complete since for every integer k, there is a staircase-type region like you see below with exactly k domino tilings (this was observed in 2014 by Philippe Nadeau).

In fact, most natural counting functions are either complete or almost complete. For example, the number of spanning trees of a simple graph is almost complete since the number of spanning trees in an n-cycle is exactly n, for all n>2. Similarly, the number of standard Young tableaux |SYT(λ)| of a partition λ is almost complete since |SYT(m,1)|=m. Many other natural examples are in our paper with Swee Hong Chan (SHC) which started this investigation.

Concise functions

Let f be an almost complete function. We say that f is concise if for all large enough k, there exist an element a ∈ An such that f(a) = k and n < C (log k)c, for some C, c>0. Just like explicit constructions in the context of Graph Theory (made famous by expanders), this notion makes perfect sense irrespectively from our applications in computational complexity (see our paper with SHC linked above).

Note that none of the simple constructions mentioned above imply that the corresponding functions are concise. This is because the size of combinatorial objects is linear in each case, not poly-logarithmic as we need it to be. For the number of perfect matchings, an elegant construction by Brualdi and Newman (1965) shows that one can take n = O(log k). This is the oldest result that we know, that some natural combinatorial counting function is concise.

For the number of domino tilings, SHC and I proved an optimal bound: there is a region with O(log k) squares with exactly k domino tilings. The proof is entirely elementary, accessible to a High School student. The idea is to give explicit transformations k → 2k and k → 2k-1 using gadgets of the following kind:

As always, there are minor technical details in this construction, but the important takeaway is that we obtain an optimal bound, but the regions we construct are not simply-connected. For simply-connected regions the best bound we have is O(log k log log k) for the snake (ribbon) regions, via connection to continued fractions that was recently popularized by Schiffler. Whether one can obtain O(log k) bound in this case is an interesting open problem, see §6.4 in our paper with SHC.

Many concise functions

For the number of spanning trees, whether this function is concise remained an open problem for over 50 years. Even a sublinear bound was open. The problem was recently resolved by Stong in this beautiful paper, where he gave O((log k)3/2/(log log k)) upper bound. Sedláček (1967) conjectured that o(log k) bound for general graphs, a conjecture which remains wide open.

For some functions, it is easy to see that they are not concise. For example, for a partition λ of n, the number of standard Young tableaux |SYT(λ)| is a divisor of n! Thus, for k prime, one cannot take n<k in this case.

Curiously, there exist functions, for which being almost complete and concise are equivalent notions. For example, let T ∈ R2 be a set of n points in general positions in the plane. Denote by g(T) the number of triangulations of T. Is g almost complete? We don’t know but my guess is yes, see Conjecture 6.4 in our paper with SHC. However, we do know exponential lower and upper bounds Cn < g(T) <Dn. Thus, if g is almost complete it is automatically concise with an optimal O(log k) upper bound.

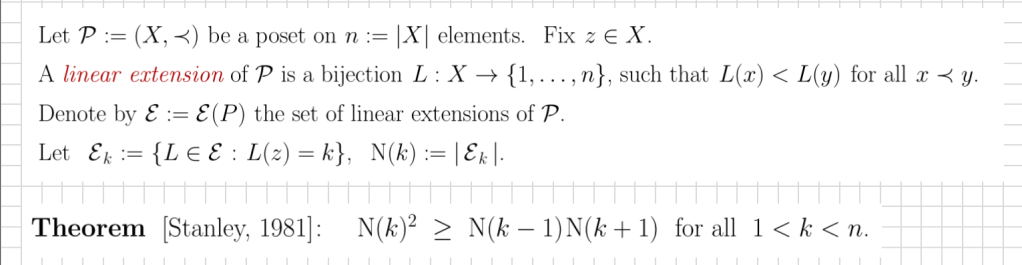

Our final example is much too amusing to be skipped. Let e(P) denote the number of linear extensions of a poset on n elements. This function generalized the number of standard Young tableaux, and appears in a number of applications (see our recent survey with SHC). Tenner proved a O(√k) bound, the first sublinear bound. The conciseness was shown recently by Kravitz and Sah, where they established O(log k log log k) upper bound. The authors conjectured O(log k) bound, but potentially even O((log k)/(log log k)) might hold.

Consider now a restriction of the function e to posets of height two. In our paper with SHC, we have Conjecture 5.17 which claims that such e is still almost complete. In other words, for all large enough k, one can find a poset of height two with exactly k linear extensions. Since the number of linear extensions of such posets is at least (n/2)!2 this would give an optimal bound for general posets as well, so a very sharp extension of the Kravitz–Sah bound. We should mention an observation of Soukup (p. 80), that 13,168,189,439,999 is not the number of linear extensions of a height two poset. This suggests that our conjecture is either false, or likely to be very hard.

Latest news: back to spanning trees

In our most recent paper with Swee Hong Chan and Alex Kontorovich, we resolve one Sedláček’s question and advance another. We study the number τ(G) of spanning trees in a simple planar graph G on n vertices. This function τ is concise by Stong’s theorem (his construction is planar), and it is easy to show by planarity that τ(G) < 6n. Thus, a logarithmic upper bound O(log k) is the best one can hope for. Clearly, proving such result would be a major advancement over Stong’s poly-logarithmic bound.

While we don’t prove O(log k) bound, we do get very close — we prove that this bound holds for the set of integers k of density 1. The proof is both unusual (to me as a combinatorialist), and involves a mixture of graph theory, number theory, ergodic theory, and some pure luck. Notably, the paper used the remarkable Bourgain–Kontorovich technology developed towards the celebrated Zaremba’s Conjecture. You can read it all in the paper or this longish post by Alex.

P.S. Being stubborn and all, I remain opposed to the “unity of mathematics” philosophy (see this blog post which I wrote about the ICM before later events made it obsolete). But I do understand what people mean when they say these words — something like what happened in our paper with Alex and Swee Hong with its interdisciplinary tools and ideas. And yet, to me the paper is squarely in Combinatorics — we just use some funky non-combinatorial tools to get the result.

Princeton President to Princeton Jews: For the sake of free speech please shut up!

The readers of this blog know know that I stay away from non-math related discussions. It’s not that I don’t have any political opinions, I just don’t think they are especially valuable or original. I do however get triggered by a clear anti-Semitism, discrimination of Jews by the universities, and by personal disrespect. The story below is a strange mixture of these.

As I was visiting the IAS in Princeton, I had the dubious fortune to attend a speech by Christopher Eisgruber last week. Eisgruber has been Princeton’s President since 2013 and a long time Princetonian. To say I was disappointed is to say nothing — I was appalled by the condescension and the lack of empathy. But I think President Eisgruber left feeling that it was a successful event. Let me set the scene first before I explain what happened.

Last Saturday was Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, the day of atonement and repentance. This is also a day of remembering the dead, and there were a lot of deaths to remember this year. This is also a day to recognize rising antisemitism and pray for peace.

President Eisgruber was invited to speak at the Jewish Center, Princeton’s leading Conservative congregation. I think he was invited not as an expert on Constitutional Law (which he is), but as a President of a major research university with a sizable Jewish community that has been suffering for the past year and is in desperate need of healing.

It seems, President Eisgruber had not noticed. The speech he chose to give was on freedom of speech and how great (well, excellent!) Princeton is doing in that regard (oh, joy!) And how happy and satisfied was the Princeton Jewish community in the past year (wait, what? really?)

President Eisgruber explained at great length the importance of free speech, including the offensive speech. That it’s vital for productive debate. That as a private university Princeton could do more, of course, but he is absolutely uninterested in policing speech beyond constitutional requirements.

Now, I spent over 30 years in academia in the US, so I heard it all before. Probably everyone in academia has. It’s fine in the abstract. The reality is different. By now, everyone on a major university campus is well familiar with universities’ proclivities towards protecting one kind of speech and not protecting the other. Eisgruber’s speech was epitome of this hypocrisy, highlighted by the setting and aggravated by insensitivity of his answers.

During the Q&A, President Eisgruber clarified that all those anti-Israel slogans like “from the river to the sea…” and “globalize the intifada” that were heard on campus are nothing to worry about. Because you see, they have a committee which looked at those slogans and concluded they are not anti-Semitic, at least not always (depending on the context, perhaps?) Because even The New York Times (apparently, a reputable authority on the subject) concluded that these slogans mean different things to different people, so it’s all good. In fact, he continued,

I sincerely believe that even the majority of those who said these things are not anti-Semitic.

Whether he believes it’s ok to have an anti-Semitic minority on Princeton campus was never clarified.

At this point President Eisgruber hedged and said that “we must remember” that it’s not about whether the Jewish community is offended, but rather whether the speech is constitutionally permissible. Without ever disclosing his personal views, he double-hedged and mentioned one Middle Eastern scholar at Princeton, who suggested that these slogans are simply in bad taste. And like all things Princetonian, that scholar must be the world’s leading authority (I am paraphrasing).

President Eisgruber then triple-hedged and mentioned that he “promised to the general council” to say that those who are still aggrieved should not ask him (“I don’t decide these things”), but rather can again petition that all-powerful committee presiding over permissible speech. He slyly smirked at the audience and suggested that if we lose that’s also ok, because being offended is just part of life…

When a brave Princeton faculty asked for his views on speech against other marginalized communities, he was unable to get out of the hole he just dug for himself. So he chose to lie. He said he would be ok to have such an offensive speech, that it really doesn’t matter against what community is the speech. Not a soul in the audience believed him, obviously, even the 13 year olds knew better.

Asked to give examples, he stiffened for a second, but then started stalling. He recalled a booth on a sidewalk which spewed ani-gay propaganda at students. He admitted that of course that booth was on public property, so even if he wanted to shut it down he couldn’t. But even if he could, maybe he wouldn’t, that even though he hated that speech, it was allowed under the Constitution, although it did make bad news at the time, but that’s ok. Ugh… At that point, the answer lasted long enough for the audience to forget what was the question, which was the intent I presume.

Most appallingly, President Eisgruber explained to us that apparently the Princeton Jewish community is “thriving”. Are you sure that Princeton students are any different in their views from the UC students, Mr. President? Although this is his first time ever giving a talk in a synagogue (he thought he was bragging, I think), he “had seen student surveys” which proved that

Last year, the Jewish students at Princeton were more satisfied than in previous years.

He didn’t give any numbers, so it’s hard to know what level of satisfaction is he even talking about. How bad exactly were these numbers to begin with, that they hadn’t significantly dropped? Please make them public, so we can take a look! For example, in 2022 UCLA did make their surveys public and we can easily read the bottom of this table:

What President Eisgruber is saying is so much contrary to common sense, you have to be blind, deaf and have no access to social media to believe that. A simple Google search would suggest that Princeton Has Become a Hostile Place for Jews and produce this report card. There is even an official Title VI investigation by the US Department of Education into into Princeton over alleged antisemitism on campus. Great job, Mr. President!

I would be amiss to say that President Eisgruber showed no empathy at all. He did, when he lamented:

I feel so bad for presidents of other universities who had to testify for three hours under bright lights!

I don’t think either of these presidents were in the audience, but I am sure they would have appreciated the sentiment. (Full disclosure: UCLA former Chancellor Gene Block also testified to the House Committee.)

Now, university presidents are basically politicians. Good politicians know how to read the audience and can fake empathy. Bad politicians recycle old speeches written for donors and dwell on tedious legal details. Clearly, President Eisgruber is either a really terrible politician, or has been at the job for so long that he simply stopped caring.

I have several theories of what happened. Maybe he thought that his story of a Holocaust survivor grandfather would give him cover to say anything. Or maybe he thought that this was a private event closed to outsiders, and these Princeton Jewish folks are just too invested in the community to voice a protest. Or maybe he just loves Constitutional Law and has nothing else to say. Perhaps, all of the above.

But my favorite theory is that he thought he was helping. Clearly, after you tell people who are suffering “don’t feel bad” they will feel an instant relief, right? Because, you see, whatever we are feeling is not Princeton University’s fault, it’s all fault of the ever so binding US Constitution…

I hate to speculate if President Eisgruber gives the same kind of speeches to other marginalized communities. But if that’s the case, maybe it’s time to follow all those “other university presidents” and resign. Let us grieve and suffer in peace without you lecturing us on how we should feel and admonishing us for wanting equal treatment or just to feel safe on campus.

You clearly care a great deal about the law, Mr. President, so maybe you can get back to doing it full time? Please leave the presidency to someone who has at least an ounce of empathy.

The bunkbed conjecture is false

What follows is an unusual story of perseverance. We start with a conjecture and after some plot twists end up discussing the meaning of truth. While the title is a spoiler, you might not be able to guess how we got there…

The conjecture

The bunkbed conjecture (BBC) is a basic claim about random subgraphs. Start with a finite graph G=(V,E) and consider a product graph G x K2 obtained by connecting the corresponding vertices on levels V(1) and V(2). Sort of like a bunkbed. Now consider random subgraphs of a this product graph.

Bunkbed Conjecture: The probability that vertices u(1) and v(1) are connected is greater or equal than the probability that vertices u(1) and v(2) are connected.

In other words, the probability of connecting two vertices on the same level cannot be smaller than when connect vertices on different levels. This is completely obvious, of course! And yet the conjecture this problem defeated several generations of probabilists and remained open until now. For a good reason, of course. It was false!

The origins of the conjecture are murky, but according to van den Berg and Kahn it was conjectured by Kasteleyn in the early 1980s. There are many versions of this conjecture; notably one can condition on the subset of vertical edges and ask the same question. Many partial results are known, as well as results for other probabilistic models. The conjecture is false nonetheless!

The direction

Why look for a counterexample if the conjecture is so obviously true? Well, because you always should. For any conjecture. Especially if everyone else is so sure, as in completely absolutely sure without a doubt, that the conjecture is true. What if they are all wrong? I discuss this at length in this blog post, so there is no need to rehash this point.

The counterexample

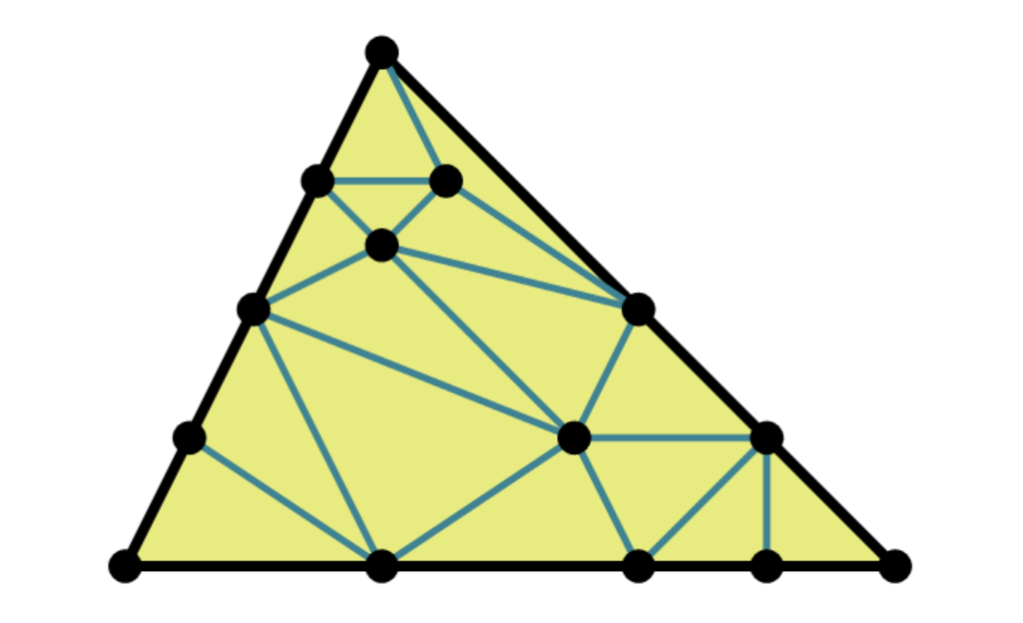

We disprove the conjecture in a joint paper with Nikita Gladkov (UCLA) and Alexandr Zimin (MIT), both graduate students. Roughly speaking we take the following 3-hypergraph from a recent paper by Hollom.

We then replace each yellow triangle with the following gadget using n=1204, placing a in the shaded vertex, while v1 and vn are placed in the other vertices of the triangle (so the red path goes into the red path). For a stronger version of the conjecture that’s all there is. For a weaker version, some additional tweaks needed to be made (they are not so important). And we are done!

The resulting graph is has 7523 vertices and 15654 edges. The difference between probabilities for paths between u1 and u10 at the same and different levels as in the conjecture is astronomically small, on the order of -10-6500. But it’s negative, which is all we need. Very very roughly speaking, the red path is the only path which avoids shaded vertices and creates a certain bias which give this probability gap. Formalizing this is a bit technical.

The experiments

Of course, the obvious way to verify our counterexample computationally would fail miserably — the graph is much too large. Instead, we give a relatively elementary completely combinatorial disproof of the BBC that is accessible to a wide audience. I would rather not rehash technical details and ideas in the proof — it’s all in our paper, which is only 12 pages! See also the GitHub code and some explanation.

I do want to mention that giving formal disproof was not our first choice. It’s what we ended up doing after many failures. There is always a bit of a stigma people have about publicly discussing their failures. I know very few examples, only this one famous enough to be mentioned. So let me mention briefly how we failed.

Since I was sure the bunkbed conjecture is false (for reasons somewhat different from my contrarian philosophy), we started with a myriad of computer experiments trying all small graphs. When those failed, we tried to use AI and other computer assisted tools. We burned many hours on a giant UCLA Hoffman2 Cluster getting closer for a while. In hindsight, we didn’t look in the right place, obviously. After several months of computer experiments and no clear counterexample, it felt we are wasting time. We then thought a bit more about philosophy of what we are doing and stopped.

Before I tell you why we stopped, let me make a general recommendation. Please do try computer experiments for whatever you are working on. Make an effort to think it through and design a good experiment. Work hard to test as much as your computer technology allows. If you need some computing power, ask around. Your university might just have the resources. Occasionally, you can even ask a private company to donate theirs.

If you succeed, write a paper and publish it. Make your code and work notes publicly available. If you fail, do exactly the same. If the journals refuse to publish your paper, just keep it on the arXiv. Other people in your area would want to know. And as far as the NSF is concerned, all of this is “work product”. You can’t change the nature of the problem and the results you are getting, but you deserve the credit regardless.

Let me repeat: Do not fear telling other you have not succeeded in your computer testing. Fear others making the same mistakes or repeating the same work that you did.

The curse

One reason we stopped is because in our initial rush to testing we failed to contemplate the implications of Monte Carlo testing of even moderately large graphs. Here is a quote from the paper:

Suppose we did find a potential counterexample graph with only m=100 edges and the probability gap was large enough to be statistically detectable. Since analyzing all of 2m ≈ 1030 subgraphs is not feasible, our Monte Carlo simulations could only confirm the desired inequality with high probability. While this probability could be amplified by repeated testing, one could never formally disprove the bunkbed conjecture this way, of course.

This raises somewhat uncomfortable questions whether the mathematical community is ready to live with an uncertainty over validity of formal claims that are only known with high probability. It is also unclear whether in this imaginary world the granting agencies would be willing to support costly computational projects to further increase such probabilities (cf. [Garrabrant+’16], [Zeilberger’93]). Fortunately, our failed computational effort avoided this dystopian reality, and we were able to disprove the bunkbed conjecture by a formal argument.

Societal implications aside, it is an interesting question whether a reputable math journal should accept a counterexample that is tested with 99.99% confidence, and the results can be replicated and rechecked by others. Five sigma may be a gold standard in nuclear physics, but math journals tend to prefer 100% correctness (even though some papers they publish are 100% incorrect).

What I do know, is that most journals would refuse to even consider a “five sigma counterexample”. While details of the situations differ quite a bit, I knew what happened to the (rather interesting) Sills–Zeilberger paper, which was eventually published, but not after several desk rejections. But PhD students need jobs in reality, not in theory. That is really why we stopped. Why persevere and create controversy when you can just try doing something else?

P.S. There is yet another layer to all of this. Back in 1999, I asked Avi Wigderson if P=BPP? He said “Yes“. Last week I asked him again. This is 25 years later, almost to the day. He said “Yes, I am absolutely sure of that.” It’s one of his favorite conjectures, of course. If he is right, every probabilistic counterexample can be turned into deterministic. In other words, there would be a fully rigorous way to estimate both probabilities and prove on a computer that the conjecture is false. But you must have guessed what I was thinking when I heard what he said — now he used “absolutely sure“…

P.P.S. There is a very nice YouTube video about our paper made by Trefor Bazett. Another (even better) YouTube video by Johann Beurich (in German). See also this article in Quanta Magazine, this in IFLScience, that in Pour la Science (in French) and that in Security Lab (in Russian) about our work and this blog post.

UPDATE (June 13, 2025). This took awhile, but the paper was just published at PNAS.

We deserve better journals

By and large, math journals treat the authors like a pesky annoyance, sort of the way a local electric company treats its customers. As in — yes, serving you is our business, but if you don’t like our customer service where else are you going to go? Not all editors operate that way, absolutely not all referees, but so many it’s an accepted norm. We all know that and all play some role in the system. And we all can do better, because we deserve better.

In fact, many well meaning mathematicians do become journal editors, start new journals, and even join the AMS and other professional societies’ governing bodies which oversee the journals. This helps sometimes, but they quickly burn out or get disillusioned. At the end, this only makes second order improvements while the giant sclerotic system continues its descent from bad to worse.

Like everyone else, I took this as a given. I even made some excuses: evil publishers, the overwhelming growth of submissions, everyone stressed and overworked, papers becoming more technical and harder to referee, etc., etc. For decades I watched many math journals turn from friendly if not particularly warm communal endeavors, to zones of hostility.

Only most recently, it occurred to me that it doesn’t have to be this way. We should have better journals, and we deserve a better treatment (I was really off the mark in my first line of this post). Demanding better journals is neither a fantasy nor a manifesto. In fact, physicists have already figured it all out. This post is largely about how they do it, with some lessons and suggestions.

What we have

If you don’t know what I am talking about, walk to any mathematician you see at a conference. If you have a choice, choose the one who looks bored, staring intensely at their shoes. Ask them for their most frustrating journal publishing story. You may as well sit down — the answer might take awhile. Even if they don’t know you (or maybe especially if they don’t know you), they will just unload a litany of the most horrifying stories that would make you question the sanity of people staying in this profession.

Then ask them why do they persevere and keep submitting and resubmitting their papers given that the arXiv is a perfectly fine way to disseminate their work. You won’t hear a coherent answer, but rather the usual fruit salad of practical matters: something about jobs, CVs, graduate students, grants, Deans, promotions, etc. Nobody will ever mention that their goal is to increase their readership, verify the arguments, improve their presentation style, etc., ostensibly the purpose of mathematical journals.

While my personal experience is a relatively happy one, I do have some scars to show and some stories to tell (see this, that and a bit in that blog posts on publishing struggles). There is no need to rehash them. I also know numerous stories of many people because I have asked them these questions. In fact, every time I publish something like this blog post (about the journals’ hall of shame), I get a host of new horror stories by email, with an understanding that I am not allowed to share them.

The adversarial relationship and countless bad experiences make it is easy to lose sight of the big picture. In many ways we are privileged in mathematics to have relatively few bad and for-profit actors. Money and grant funding matters less. We don’t have extreme urgency to publish. We have some relatively objective ways to evaluate papers (by checking the proofs). One really can work on the Moon, as long as one has a laptop and unlimited internet (and breathable air, I suppose).

We have it good, or at least we did when we started sliding into abyss. Because the alarms are not ringing, the innovation in response has stuttered. We are all just chugging along. Indeed, other than a few new online journals, relatively little has changed in the past two decades.

This is in sharp contrast with physics, which had very few of the advantages that math has (depending on the area). Besieged on all sides, physics community was forced to adapt faster and arguably better in response to changes in the publishing landscape. In fact, the innovations they made are so natural to them, their eyes open wide in disbelief when they hear how we continue to publish math papers.

The following is a story of the Physical Review E (PRE), one of the journals of the American Physical Society (APS). I will start with what I learned about the PRE and APS inner working, their culture, successes and challenges, some of which ring very familiar. Only afterwards I will get back to math publishing, the AMS and how we squandered our advantages.

What’s special about PRE?

I chose to write about the PRE because I published my own paper there and enjoyed the experience. To learn more about the journal, I spoke to a number of people affiliated with PRE in different capacities, from the management to members of the Editorial Board, to frequent authors and reviewers. These interviews were rather extensive and the differences with the math publishing culture are much too vast to summarize in a single blog post. I will only highlight things I personally found remarkable, and a few smaller things that can be easily emulated by math journals.

PRE’s place in the physics journal universe

PRE is one of five similarly named “area journals”: PRA, PRB, etc. More generally, it is one of 18 journals of the APS. Other journals include Physical Review Letters (PRL is APS’s flagship journal which published only very short papers), Physical Review X (PRX is another APS’s leading journal, online only, gold open access, publishes longer articles, extremely selective), Reviews of Modern Physics (APS’s highest cited journal which publishes only survey articles), and a number of more specialized journals.

The APS is roughly similar to the the AMS in its prominence and reach in the US. APS’s main publishing competition include the Institute of Physics (IOP, a UK physics society with 85 titles, roughly similar to the LMS), Nature Portfolio (a division of Springer Nature with 156 titles only a few of them in physics), and to a lesser extent Science by AAAS, various Elsevier, SIAM journals, and some MDPI titles.

Journal structure

The PRE editorial structure is rather complicated. Most of the editorial work is done by an assortment of Associate Editors, some of whom are employed full time by the APS (all of them physics PhD’s), and some are faculty in physics or adjacent fields from around the world, typically full time employed at research universities. Such Associate Editors receive a 2 year renewable contract and sometimes work with the APS for many years. Both professional and part time editors do a lot of work handling papers, rejecting some papers outright, inviting referees, etc.

The leadership of PRE is currently in flux, but until recently included Managing Editor, a full time APS employee responsible for running the journal (such as overseeing the work of associate editors), and a university based Lead Editor overseeing the research direction. The APS is currently reviewing applications for a newly created position of Chief Editor who will presumably replace Managing Editor, and is supposed to oversee the work of the Lead Editor and the rest of the editorial team (see this ad).

There is also an “Editorial Board”, whose name might be confusing to math readers. This is really a board of appeals (more on this later), where people serve a 3 year term without pay, giving occasional advice to associate editors and lending their credibility to the journal. Serving on the Editorial Board is both a service to the community and minor honor.

Submissions

The APS is aware of the role the arXiv plays in the community as the main dissemination venue, with journals as an afterthought. So it encourages submissions consisting of arXiv numbers and subject areas. Note that this makes it different from Nature and Science titles, which forbid arXiv or other online postings both for copyright reasons and so not to spoil future headline worthy press releases.

The submissions to all APS journals are required to be in a house two column style with a tiny font. Тhere are sharp word count limits for the “letters” (short communications) and the “articles”. These are rather annoying to calculate (how do you count formulas? tables?), and the journals’ online software is leaves much to be desired.

Desk rejections

At PRE, about 15-20% of all papers are rejected within days after the initial screening by managing or associate editors, who then assign the remaining papers according to research areas. Some associate editors are reluctant to do this at all, and favor at least one report supplemented by initial judgement. This percentage is a little lower than at the (more selective) PRL where it is reported to be 20-25%. Note that all APS journals pay special attention to the style, so it’s important to make an effort to avoid being rejected by a non-expert just because of that.

Curiously, before 2004, the percentage was even lower at PRL, but the APS did some rather interesting research on the issue. It concluded that such papers consume a lot of resources and rarely survive the review process (see this report). Of course, this percentage is relatively low by math standards — several math journals I know have about 30-50% desk rejections, with another 30-40% after a few quick opinions. On the other hand, at Science, over 83% papers get rejected without an external review.

Review process

Almost all the work is handled by associate editors closest to the area. The APS made a major overhaul of its classification of physics areas in 2016, to bring it to modern age (from the old one which resembles the AMS MSC). Note aside: I have been an advocate for an overhaul of MSC for a while, which I called a “historical anachronism” in this long MO answer (itself written about 14 years ago). At the very least the MSC should upgrade its tree structure (with weird horizontal “see also…” links) to a more appropriate poset structure.

Now, associate editors start with desk rejections. If the paper looks publishable, they send it to referees with the goal of obtaining two reports. The papers tend to be much shorter and more readable by the general scientific audience compared with the average math paper, and good style is emphasized as a goal. The reviewers are given only three weeks to write the report, but that time can be extended upon request (by a few more weeks, not months).

Typically, editors aim to finish the first round in three months, so the paper can be published in under six months. Only few papers lag beyond six months at which point, the editors told me, they get genuinely embarrassed. The reason is often an extreme difficulty in finding referees. Asking 4-8 potential referees is normal, but on rare occasions the numbers can be as high as 10-20.

Acceptance rate

In total, PRE receives about 3,500-4,000 submissions a year, of which about 55-60% get accepted, an astonishingly high percentage when compared to even second tier math journals. The number of submissions has been slowly decreasing in recent years, perhaps reflecting many new publications venues. Some editors/authors mentioned MDPI as new evil force (I called MDPI parasitic rather than predatory in this blog post).

For comparison, PRL is an even bigger operation which handles over twice as many papers. I estimate that PRL accepts roughly 20-25% of submissions, probably the lowest rate of all APS journals. In a more extreme behavior, Nature accepts about 8% submissions to publish about 800 papers, while Science accepts about 6% submissions to publish about 640 papers per year.

It is worth putting number published paper in perspective by comparing them with other journals. PRE and PRL publish about 1,800 and 2,100 papers per year, respectively. Other APS journals publish even more: PRD publishes about 4,000, and PRB close to 5,000 papers a year.

For math journals true acceptance ratios are hard to find and these numbers tend to be meaningless anyway due to self-selection and high cost of waiting for rejection. But numbers of published papers are easily available: Jour. AMS publishes about 25, Mathematika about 50, Proc. LMS about 60, Forum Math. Sigma in the range of 60-120, Bull. LMS in the range of 100-150, Trans. AMS about 250, Adv. Math. about 350, IMRN in the range of 300-500, and Proc. AMS about 450 papers per year. These are boutique numbers compared to the APS editorial machine. In the opposite extreme, MDPI Mathematics recently achieved the output of about 5,000 papers a year (I am sure they are very proud).

Publication

When a paper is accepted at PRE, it is sent to production which APS outsources. There are two quick rounds of approval of LaTeX versions compiled in the house style and proofread by a professional. It then gets published online with a unique identifier, usually within 2-3 weeks from the date of acceptance. Old fashioned volumes and numbers do exist, but of no consequence as they are functions of the publication date. There is zero backlog.

Strictly speaking there is still a print version of the PRE. I was told it is delivered to about 30 libraries worldwide that apparently are unconcerned with deforestation and willing to pay the premium. In truth, nobody really wants to read these paper versions. The volumes are so thick and heavy, it is hard to even lift them up from a library shelf. Not to dwell on this too much, but some graduate students I know are unaware even which building houses our math library at UCLA. It’s hard to blame them, especially after COVID…

Appeals

When a paper is rejected, the authors have the right to appeal the decision. The paper is sent to a member of the Editorial Board closest to the area. The editor reads both the paper and the referee reports, then writes their own report, which they sign and send to the authors. More often than not the decision is confirmed, but reversals do happen.

Since what’s “important” is ultimately subjective, appeals serve an important check on Associate Editors and helps keep peace in the community. Numerically, only about 3-5% of rejected papers are sent for an appeal, about 2-3 papers per Editorial Board member each year.

Embarrassingly for the whole field, I cannot think of a single math journal with an appeals process (except, interestingly, for MDPI Mathematics, which famously has the selectivity of a waste bucket). Even Nature has an appeals process, and nobody ever thinks of them as too friendly.

Note: some math journals do allow resubmissions of previously rejected papers. These papers tend to be major revisions of previous versions and typically go the same editor, defeating the point of the appeal.

Editorial system

The APS has its own online editorial system which handles the submissions, and has an unprecedented level of transparency compared to that of math journals I am familiar with. The authors can see a complete log of dates of communications with (anonymized) referees, the actions of editors, etc. In math, the best you can get is “under review” which brings cold comfort.

The editors work as a team, jointly handling all incoming email and submission/resubmission traffic. Routine tasks like forwarding the revision to the first round referees are handled by first person available, but the editorial decisions (accept/reject, choices of referees), are made by the assigned Associate Editor. If an Associate Editor has a week long backlog or is expecting some inactivity, his queue is immediately redistributed between other editors.

Relations between APS journals

Many PRE papers first arrive to PRL where they are quickly rejected. The editorial system allows editors from one journal see all actions and reports in all other APS journals. If the rejected PRL paper fits the scope of PRE and there are reports suggesting PRE might be suitable, PRE editors try to invite such papers. This speeds up the process and simplifies life to everyone involved.

For longer papers, PRE editors also browse rejections from PRX, etc. From time to time, business oriented managers at the APS raise a possibility of creating a lower tier journal where they would publish many papers rejected from PRA–PRE (translation: “why shouldn’t APS get some of MDPI money?”), but the approach to maintain standards keep winning for now. From what I hear, this might change soon enough…

Note: In principle, several editorial systems by Elsevier and the like, do allow transferring papers between math journals. In practice, I haven’t seen this feature ever used (I could be wrong). Additionally, often there are firewalls which preclude editors in one journal from see reports in the other, making the feature useless.

Survey articles

The APS publishes Reviews of Modern Physics, which is fully dedicated to survey articles. Associate Editors are given a budget to solicit such articles and incentivize the authors by paying them about $1,500 for completion within a year, but only $750 is the project took longer. The articles vary in length and scope, from about 15 to about 70 pages (when converted from APS to the bulky AMS style, these pages numbers would more than double). There are also independent submissions which very rarely get accepted as the journal aims to maintain its reputation and relevance. Among all APS publications, this journal is best cited by a wide margin.

We note that there are very few math journals dedicated to surveys, despite a substantial need for expository work. Besides Proc. ICM and Séminaire Bourbaki series which are by invitation only, we single out the Bull. AMS, EMS Surveys and Russian Math Surveys (in Russian, but translated by IOP). Despite Rota’s claim “You are more likely to be remembered by your expository work“, publishing surveys remains difficult unless you opt for a special issue or a conference proceedings. In the last two years I wrote two rather long surveys — on combinatorial interpretations and on linear extensions. Word of advice: if you want to have an easy academic life I don’t recommend doing that — they just eat up your time.

At PRE, there are no surveys, but the editors occasionally solicit “perspectives”. These are forward looking articles suggesting important questions and directions (more like public NSF grant applications than surveys). They publish about five such articles a years, hoping to bring the number up to about ten in the future.

Profiled articles

In 2014, following the approach of popular magazines, PRE started making “Editors’ Suggestions”. These are a small number of articles the editors chose to highlight, both formally and on the website. They are viewed as minor research award that can be listed on CVs by the authors.

Outstanding referee award

The APS instituted this award in 2008, to encourage quick and thorough refereeing. This is a lifetime award and comes with a diploma size plaque which can be hang on the wall. More importantly, it can be submitted to your Department Chair and your friendly Dean as a community validation of your otherwise anonymous efforts.

Each year, there are a total of about 150 awardees selected across all APS journals (out of tens of thousands referees), of which about 10 are from PRE. This selection is taken very seriously. The nominations are done by Associate Editors and then discussed at the editorial meetings. For further details, see this 2009 article about the award by the former Editor-in-Chief of Physical Reviews, which ends with

We feel that the award program has been most successful, and we will be continuing it at APS. [Gene D. Sprouse, Recognizing referees at the American Physical Society]

Note that such distinguished referee awards are not limited to APS or even physics. It’s a simple idea which occurred to journals across “practical” disciplines: accounting, finance, economic geography, economics, public management, regional science, etc., but also e.g. in atmospheric chemistry and philosophy. Why wouldn’t a single math journal have such an award?? Count be flabbergasted.

Community relations

As we mentioned above, in much of physics, the arXiv is a preferred publication venue since the field tends to develop at rapid pace, so strictly speaking the journal publications are not necessary. In some areas, a publication in Nature or Science is key to success, especially for a junior researcher, so the authors are often willing to endure various associated indignities (including no arXiv postings) and if successful pay for the privilege. However, in many theoretical and non-headline worthy areas, these journals are not an option, which is where PRL, PRE and other APS journals come in.

In a way, PRE operates as a digital local newspaper which provides service to the community in the friendliest way possible. It validates the significance of papers needed for job related purposes, helps the authors to improve the style, does not bite newcomers, and does not second guess their experimental finding (there are other venues which do that). It provides a quick turn around and rarely rejects even moderately good papers.

When I asked both the editors and the authors how they feel about PRE, I heard a lot of warmth, the type of feeling I have not heard from anyone towards math journals. There is a feeling of community when the editors tell me that they often publish their own papers at PRE, when the authors want to become editors, etc. In contrast, I heard a lot of vitriol towards Nature and Science, and an outright disdain towards MDPI physics journals.

It could be that my sample size was too small and heavily biased. Indeed, when I polled the authors of MDPI Mathematics (a flagship MDPI journal), most authors expressed high level of satisfaction with the journal, that they would consider submitting there again. One of my heroes, Ravi P. Agarwal who I profiled in this blog post, published an astounding 37 papers in that journal, which clearly found its target audience (so much that it stopped spamming people, or maybe it’s just me).

Note aside: Personally, the only journal I actually cared about was the storied JCTA where my senior colleague Bruce Rothschild was the Editor in Chief for 25 years, and where I would publish my best combinatorics papers. In 2020, the editorial board resigned in mass and formed Combin. Theory. I am afraid, my feelings have not transferred to CT, nor have they stayed with JCTA which continues to publish. They just evaporated.

Money matters

Despite a small army of professional editors, the APS journals provide a healthy albeit slowly decreasing revenue stream (about $43 mil. in 2022, combined from all journals, see 2022 tax disclosures on ProPublica website). The journals are turning a profit for the APS (spent on managers and various APS activities) despite all the expenses. They are spending more and making more money than the AMS (compare with their 2022 tax disclosures on ProPublica). There is much more to say here, but this post is already super long and the fun part is only starting.

Back to math journals

In the 20th century world with its print publishing, having a local peer review print journals made sense. A university of a group of universities would join forces with a local publisher and starts the presses. That’s where local faculty would publish their own papers, that’s where they would publish conference proceeding, etc. How else do you explain Duke Mathematical Journal, Israel Journal of Mathematics, Moscow Mathematical Journal, Pacific Journal of Mathematics, and Siberian Journal of Mathematics? I made a lot of fun at the geographical titles in this blog post, and I maintain that they sound completely outdated (I published in all five of these, naturally).

Now, in the 21st century, do we really need math journals? This may sound like a ridiculous question, with two standard replies:

- We need peer review, i.e. some entity must provide a certificate that someone anonymous read the paper and takes responsibility for its validity (sound weak isn’t it?).

- We need formal validation, i.e. we need to have something to write on our CVs. Different journals have different levels of prestige associated with them leading to distinctions in research recognition (and thus jobs, promotions, grants, etc.)

Fair enough, but are you sure that the journals as we have them are the best vehicles for either of these goals? Does anyone really believes that random online journals do a serious peer review? Where is this idea coming from, that the journals with its obvious biases should be conferring importance of the paper?

How are we supposed to use journals to evaluate the candidates, if these journals have uncertain rankings and in fact the relative rankings of two journals can vary depending on the area? Shouldn’t we separate the peer review aspect which makes multiple submission costly and unethical, from the evaluation aspects which desperately needs competition between the journals?

Again, this all sounds ridiculous if you don’t step back and look objectively at our publishing mess where a math paper can languish in journals for over a year, after which it is returned without a single referee report just because someone decided that at the end the paper is not good enough to be refereed. This happened to me multiple times, and to so many other people I lost count (in one instance, this happened after 3 years of waiting!)

Publishing utopia

Now, I know a lot of people whose dream publishing universe is a lot of run-by-mathematicians not for profit small online publications. It’s great to rid of Elsevier and their ilk, but it would not solve the issues above. In fact, this would bring a lot of anarchy and further loss of standards.

From my perspective, in a perfect world, “the people” (or at least the AMS), would create one mega journal, where the arXiv papers could be forwarded by the authors if they wish. Hundreds of editors (some full time, some part time) divided into arXiv subject areas, would make the initial screening, and keep say 30-40% of them to be send for review. Based on my reading of the arXiv stats, that gives about 10-15K papers a year to be refereed, a number way below what APS handles. The mega journal would only check validity and “publish” only based on correctness.

Publication at the mega journal would already be a distinction albeit a minor one. To ensure some competition, we would probably need to break this mega journal into several (say, 3-5) independently run baby megas, so the authors have a choice where to submit. In the utopia I am imagining, the level of rigor would be the same across all baby megas. It would also be a way to handle MDPI journals which would be left with a reject pile.

This wouldn’t take anything away from the top journals (think Annals) who would not want to outsource their peer review. In fact, I heard of major Annals papers studied by six (!) independent teams of referees, that’s above and beyond. But I also heard of Annals papers which seem to had no technical check at all (like this one by this guy), so the quality is maybe inconsistent.

So what about distinctions? The remnants of the existing general journals would be free from peer review. They would place bids on the best papers attracting them “modulo publication in the mega journal” with some clear set deadlines. The authors would accept the best bid, like graduate admissions, and the paper will be linked to the journal website in the “arXiv overlay” style.

Alternatively, some specialized or non-exclusive journals will make their own selections for best papers in their areas, which could be viewed as awards. One paper could get multiple such awards, and “best journal where the paper could be accepted” optimization issue would disappear completely. This would make a better, more fair world. At the very least, such awards would remove the pressure to publish in the top journals if you have a strong result.

Even better, one can imagine a competitive conference system in the style of CS theory conferences (but also in some areas of Discrete Math) emerging in this scenario. The conference submission could require a prior arXiv posting and later keep track of “verified” papers (accepted to the mega journal). When disentangled from the peer review, these conference could lead to more progress on emerging tools and ideas, and to even the playing field for researchers from small and underfunded universities across the world.

Note that there are already some awards for math papers given by third parties, but only a handful. Notably, AIM has this unusual award. More recently, a new Frontiers of Science Award was introduced for “best recent papers” (nice cash prize for a paper already published in the Annals and the like). Of course, most CS theory conferences have been giving them for decades (the papers later get published by the journals).

Would it work? Wouldn’t the mega journal be just another utility company with terrible service? Well, I don’t know and we will probably never get to find out. That’s why I called it a utopia, not a serious proposal. But it can hardly get any worse. I think pure math and CS theory are unique in requiring true correctness. When correctness is disentangled from evaluating novelty and importance, the point of the mega journal would be to help the authors get their proofs right and the papers accepted. Until then, journal editors (and referees to a smaller degree) have a conflict of interest — helping the authors might mean hurting the journal and vice versa. Guess who usually gets hurt at the end?

Back to reality

Obviously, I have no hopes that the “mega journal” would ever come to life. But NOT because it’s technically impossible or financially unsound. In other fields, communities manage somehow. The APS is a workable approximation of that egalitarian idea. Recently, eLife made another major experiment in publishing — we’ll see how that works out.

But in a professional society such as the AMS where new leadership handpicks two candidates for future leadership in a stale election? With a declining membership? Which claims the Fellow of the AMS award as it biggest achievement? Oh, please! Really, the best we can hope for is for a large “lower tier” journals with a high acceptance ratio. Why would AMS want that? I am glad you asked:

Case for higher acceptance rates at AMS journals