| CARVIEW |

Alaska

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, Alaska’s population of approximately 733,000 is 59% White (alone), 15% American Indian/Native Alaskan (alone), 12% multiracial, 7% Hispanic, and 6% Asian (alone). Given the substantial European ancestry among Hispanics, multiracial individuals, and American Indian/Native Alaskans, the overall proportion of European ancestry in Alaska is estimated at around 75%, comparable to the U.S. national average. Based on our computations, Alaska’s average Academic Achievement Quotient (ACHQ), derived from NAEP and PIAAC test scores, is 99.42, also near the U.S. average.

Academic achievement disparities by racial and ethnic groups in Alaska mirror those in the contiguous United States. NAEP main assessments (2015, 2017, 2019, 2022) for non-English language learners reveal an average math achievement gap of d = 0.93 standard deviations between White and American Indian/Native Alaskan students. IQ testing shows similar disparities. Grigorenko et al. (2004) administered the Cattell Culture Fair Test and Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale to 261 Yup’ik students (grades 9–12) in Alaska. As reported by Lynn (2016), the group scored an equivalent of IQ 86 on the non-verbal test and IQ 77 on the verbal test.

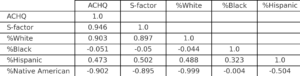

County-level data from the Stanford Education Data Archive indicate strong negative correlations between the percentage of American Indian/Native Alaskan residents and both ACHQ and an S-factor index based on rates of adults without a high school diploma, uninsured individuals, unemployment, SNAP recipients, and those living below 150% of the poverty line. These correlations persist after controlling for the percentage of Asian and Pacific Islander residents. Table 1 summarizes partial correlations between self-identified racial/ethnic (SIRE) percentages and both ACHQ and S-factor scores across 29 Alaskan counties, controlling for Asian and Pacific Islander populations.

Table 1. Partial correlations between SIRE percentages and academic achievement (ACHQ) and S-factor scores across 29 Alaskan counties, controlling for % Asian and Pacific Islander

Greenland

Greenland has a population of approximately 56,000, of which about 89% are reportedly Inuit (Bjerregaard et al., 2002). The remaining 9% consists primarily of Danes, other Europeans, and small groups such as Filipinos (Central Intelligence Agency, 2020). According to a large genetic study, the Greenlandic Inuit population has, on average, about 25% European ancestry. Based on these figures, the estimated country-wide ancestry proportions would be approximately 31% European, 67% Inuit (Amerindian), and 2% from other sources.

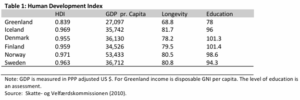

Since Greenland is a constituent country of Denmark, its Human Development Index (HDI) is not routinely reported by the UN. However, several estimates have been made for the 2008–2010 period: 0.869 (Hastings, 2009), 0.786 (Avakov et al., 2013), and 0.839 (Andersen et al., 2021). All are lower than Denmark’s HDI average of 0.93 to .95 for 2010. Summarizing the HDI components for 2010, Andersen et al. (2021) reports the following:

Table 2. Human Development Index (HDI) and component scores for Greenland and Nordic countries, as reported by Andersen et al. (2021).

Little cognitive data is available for Greenland. Becker (in View on IQ) provides an estimate of 98.89 (or 98.74 when scaled relative to the U.S. average) based on WISC Block Design scores from a sample of 40 Inuit adolescents in a study by Weihe et al. (2002). Becker excluded WISC Digit Span (SD) scores, which were low with raw scores of 2.8 and 2.3 for DS forwards and backwards, respectively, arguing that mercury exposure may have artificially lowered performance on that subtest. However, the children tested were not atypical, suggesting that if mercury exposure is affecting scores, it likely reflects a broader issue within the Greenlandic Inuit population. Using U.S. CNLSY scores as norms, computed in another post, the children’s estimated scores would be IQ 85 for Digit Span Backwards and IQ 79 for Digit Span Forwards. Averaging Block Design and Digit Span Backwards yields an estimated IQ of 92 (U.S.-normed) for the sample.

Additionally, Kleist et al., (2021) report validation results for an Greendlandic Inuit translation of The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS) dementia screen. The discussion and figures imply a mean score of around 24, significantly lower than scores found in validation studies of European populations (Nielson et al., 2019; M = 27.3; SD = 2.2).

Regarding the ACHQ, Statistics Greenland reports rates of satisfactory performance on achievement tests in Math, English, Danish, and Greenlandic. These scores are not directly comparable to Danish test scores, but analyzing student performance across Nuuk schools provides valuable insights. We examined results from top-performing schools on Danish tests. At Nuuk Internationale Friskole, a private international school, 90% of students were European, while 95% of students at Ukaliusaq were Inuit. Atuarfik Hans Lynge and Kangillinnguit had more mixed demographics and more admixed students, with approximately 50% and 33% of students, respectively, exhibiting predominantly European features. Pictures of the student bodies of the schools are shown below.

Based on percentages achieving satisfactory scores in years 2010 to 2019 we computed deviations scores relative to the Greenland average. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Deviation Scores for the Schools with the Highest Danish Language Performance in Greenland (Greenland average as reference)

| Greenlandic | English | Danish | Math | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Greenland | ref | ref | ref | ref | |

| Ukaliusaq | Public | -0.01 | -0.31 | -0.46 | 0.07 |

| Kangillinnguit Atuarfiat | Public | 0.18 | -0.90 | -0.92 | -0.11 |

| Atuarfik Hans Lynge | Public | 0.13 | -1.00 | -1.07 | -0.46 |

| Nuuk Internationale Friskole | Private | 0.57 | -1.42 | -1.34 | -0.81 |

Students at Nuuk Internationale Friskole scored 0.77 standard deviations (SD) above the Greenland average, calculated by averaging Math scores and the mean of the three language tests (English, Danish, and Greenlandic). Note, the numbers at this school were small with around 150 kids over a decade of data; estimates are not precise. This may represent an upper bound for the Danish-Greenland performance gap, as the school is selective. The extent of this selectivity is unclear, but Europeans in Greenland are often administrators, suggesting a potential cognitive advantage. If we assume these students perform 0.4 SD above the Greenland average due to selection, their residual advantage would be 0.4d. For comparison, selection for the children of U.S. military personnel at Department of Defense schools is estimated to be approximately 0.3d, where one parent is directly selected on a measure of general intelligence.

For the Admixture in Americas analyses, we will use the score of 92, derived from the average of the DS backwards and Block Design scores reported by Weihe et al. (2002). Based on our preliminary analysis of achievement data, the ACHQ is likely not below this value.

It is notable that Greenlanders in Denmark are reported to have higher educational dropout rates, increased levels of poverty, and greater incidence of homelessness (Graven et al., 2023). Additionally, Greenlanders disproportionately fail the Danish Parent Competency Test. According to Human Rights in Denmark, this may be partly due to lower measured cognitive ability scores, noting:

When the municipalities examine the basis for the forced removal of Greenlandic children in Denmark, a number of tests are generally used to measure parenting skills. But according to several sources, these tests are unsuitable because they are not adapted to the target group. Greenlandic parents risk achieving low test scores, so that it is concluded, for example, that they have reduced cognitive abilities without there being actual evidence for it. Such potential misjudgements can have far-reaching consequences for both children and parents, as they can ultimately contribute to the forced removal of a child. As stated in the memo, it is well known that, among other things, intelligence tests prepared and tested in a given context or culture cannot simply be used among other peoples or cultures. The criticism of the measurement tools used in connection with forced removals should therefore be taken seriously. In Denmark, 7 per cent of children born in Greenland and 5 per cent of children with at least one parent born in Greenland are placed outside the home, compared to 1 per cent of other children in Denmark. Testing of parenting skills among Greenlanders in Denmark. (Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2022)

Greenland is another country where more detailed research is needed on the relationship between ancestry and outcomes.

References

Andersen, T. M. (2021). The Greenlandic economy: Structure and prospects. In Greenland’s Economy and Labour Markets (pp. 11-29). Routledge.

Avakov, A. V. (2013). Quality of Life, Balance of Powers, and Nuclear Weapons, 2013: A Statistical Yearbook for Statesmen and Citizens (Vol. 6). Algora Publishing.

Bjerregaard, P., & Curtis, T. (2002). Cultural change and mental health in Greenland: the association of childhood conditions, language, and urbanization with mental health and suicidal thoughts among the Inuit of Greenland. Social Science & Medicine,

Central Intelligence Agency. (2020). The World Factbook. CIA.gov. Archived January 9, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/

Graven, V., Abrahams, M. B., & Pedersen, T. (2023). Total pain and social suffering: marginalised Greenlanders’ end-of-life in Denmark. Frontiers in Sociology, 8, 1161021.

Grigorenko, E. L., Meier, E., Lipka, J., Mohatt, G., Yanez, E., & Sternberg, R. J. (2004). Academic and practical intelligence: A case study of the

Yup’ik in Alaska. Learning and Individual Differences, 14(4), 183-207.

Hastings, D. A. (2009). Filling gaps in human development index: findings for Asia and the Pacific.

Kleist, I., Noahsen, P., Gredal, O., Riis, J., & Andersen, S. (2021). Diagnosing dementia in the Arctic: translating tools and developing and validating an algorithm for assessment of impaired cognitive function in Greenland Inuit. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 80(1), 1948247.

Lynn, R. (2006). Race differences in intelligence. Whitefish, MT: Washington Summit Publishers.

Moltke, I., Fumagalli, M., Korneliussen, T. S., Crawford, J. E., Bjerregaard, P., Jørgensen, M. E., … & Albrechtsen, A. (2015). Uncovering the genetic history of the present-day Greenlandic population. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 96(1), 54–69.

Nielsen, T. R., Segers, K., Vanderaspoilden, V., Bekkhus-Wetterberg, P., Bjørkløf, G. H., Beinhoff, U., … & Waldemar, G. (2019). Validation of the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS) in a multicultural sample across five Western European countries: diagnostic accuracy and normative data. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(2), 287-296.

Weihe, P., Hansen, J. C., Murata, K., Debes, F., Jørgensen, P. J., Steuerwald, U., … & Grandjean, P. (2002). Neurobehavioral performance of Inuit children with increased prenatal exposure to methylmercury. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 61(1), 41-49.

]]>

Table 1. Average PIAAC Literacy and Numeracy d-Values Between Non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal Individuals by Canadian Province/Territory (Mother Tongue Matches Test Language)

| Non-aboriginal / Metis d | Non-aboriginal / First Nations d | Non-aboriginal / Inuit d | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 0.21 | 0.56 | 1.18 |

| Ontario | 0.21 | 0.49 | NA |

| Manitoba | 0.23 | 0.81 | NA |

| Saskatchewan | 0.4 | 0.77 | NA |

| British Colombia | 0.22 | 0.59 | NA |

| Yukon | 0.46 | 0.87 | NA |

| Northwest Territories | 0.52 | 1.2 | 1.11 |

| Nunavut | NA | NA | 1.67 |

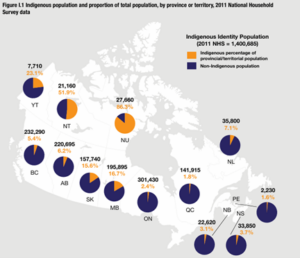

Given these disparities, along with the considerable variation in the geographic distribution of Indigenous populations, depicted in Figure 1, it is reasonable to expect that Amerindian admixture will correlate with regional cognitive outcomes—particularly with lower scores in the northern regions. In contrast, some, such as Professor Leon, have proposed that regional differences in cognitive performance reflect variation in UV radiation exposure.

Figure 1. Indigenous Population as a Percentage of the Total Population by Canadian Province/Territory

To investigate we computed first order administrative division (FOAD) cognitive and SES-related scores as follows:

1. Cognitive ability

We computed unit-weighted averages of math/numeracy and reading/literacy scores from four 21st-century assessments:

• School Achievement Indicators Program (SAIP), 2001–2002 — includes data from the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon

• Pan-Canadian Assessment Program (PCAP), 2007 and 2010 — includes Yukon

• Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), 2012 — includes the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon

• Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 2009, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2022 — limited to the provinces

PISA covers only the provinces. PCAP included Yukon in 2007 and 2010, while both SAIP and PIAAC included all three territories. The average correlation among scores from these four assessments across FOADs was r = .69, justifying their combination.

2. Province / Territory ancestry

Due to Canada’s rapid demographic change, published genetic ancestry estimates—such as those from Ancestry.com (2017)—are now outdated. More reliable estimates can be generated by weighting self-identified race/ethnicity (SIRE) percentages by the corresponding average genetic ancestry. This approach requires a few simplifying assumptions. We assume that most visible minority groups are genetically unadmixed, with the exception of Black and Latin American populations. For instance, individuals identified as Filipino are assumed to be 100% East Asian. This assumption is supported by their recent immigration history and admixture data from their countries of origin.

For Black Canadians from the West Indies, we apply admixture patterns found among Anglo-Caribbean populations, estimating an average of approximately 80% African and 20% European ancestry, while for Black Canadians from Africa we assumed 100% African ancestry. For Latin Americans—based on common countries of origin such as Mexico and Brazil—we use average admixture levels observed in U.S. Hispanic populations.

For Aboriginal groups, we rely on previously calculated admixture averages and apply them to relevant subgroups (e.g., Métis, First Nations). In cases where individuals are identified as mixed Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, we use the European Canadian average for the non-aboriginal component, given that the non-Aboriginal population in Canada has historically been overwhelmingly of European descent.

While not a perfect method, this approach is grounded in common sense and is consistent with that used by Putterman and Weil (2010).

3. HDI and S-factor scores\

We obtained HDI estimates for 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020 from Smits and Permanyer (n.d.) and averaged them. To compute S-factor scores, we used the OECD Regional Well-Being dataset (https://www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org/), applying principal factor analysis (PFA) with mean replacement. The variables included were: Education, Jobs, Income, Safety, Health, Accessibility of Services, and Housing. The first factor accounted for 61% of the total variance. Summary values are showing in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary Variables for Canadian Regions

| Region | Population | % European | % Arab | % African | % Amerindian | % East Asian | % South Asian | % Other | IQ | HDI | S-factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 36328475 | 0.705 | 0.019 | 0.04 | 0.048 | 0.093 | 0.071 | 0.024 | 100.56 | ||

| Newfoundland and Lab | 502100 | 0.883 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.085 | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 97.37 | 0.874 | 0.62 |

| Prince Edward Island | 150480 | 0.874 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.036 | 0.043 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 97.09 | 0.864 | 0.149 |

| Nova Scotia | 955860 | 0.86 | 0.011 | 0.027 | 0.048 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.006 | 98.12 | 0.872 | 0.376 |

| New Brunswick | 759195 | 0.898 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.049 | 0.017 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 97.47 | 0.866 | 0.735 |

| Quebec | 8308480 | 0.816 | 0.034 | 0.048 | 0.046 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.011 | 103.1 | 0.887 | 0.828 |

| Ontario | 14031755 | 0.644 | 0.02 | 0.051 | 0.034 | 0.106 | 0.108 | 0.037 | 101.13 | 0.899 | 0.229 |

| Manitoba | 1307185 | 0.682 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.108 | 0.105 | 0.054 | 0.012 | 97.97 | 0.869 | -0.736 |

| Saskatchewan | 1103200 | 0.752 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.11 | 0.066 | 0.041 | 0.007 | 97.74 | 0.882 | 0.496 |

| Alberta | 4177715 | 0.688 | 0.017 | 0.04 | 0.053 | 0.113 | 0.071 | 0.018 | 101.83 | 0.902 | 0.791 |

| British Columbia | 4915940 | 0.624 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.045 | 0.186 | 0.096 | 0.03 | 100.65 | 0.895 | 1.184 |

| Yukon | 39585 | 0.737 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.142 | 0.076 | 0.026 | 0.005 | 97.48 | 0.866 | -0.778 |

| Northwest Territories | 40380 | 0.539 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.345 | 0.062 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 94.03 | 0.893 | -1.433 |

| Nunavut | 36600 | 0.199 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.768 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 81.47 | 0.801 | -2.461 |

Table 3 presents partial correlations—weighted by the square root of population size—with non-focal ancestry (i.e., ancestry other than Amerindian, African, and European) statistically controlled. European ancestry is positively associated with IQ, the S-factor, and HDI, while Amerindian ancestry is negatively associated with all three outcomes. African ancestry shows a positive association with IQ and HDI; however, this likely reflects the settlement of highly selected African immigrants in high-performing FOADs such as Ontario and Quebec. Many of these individuals are recent migrants with elevated educational and occupational profiles. As such, their characteristics—like those of Asian immigrants—do not reflect historical admixture patterns and therefore fall outside the intended scope of our Admixture in the Americas project.

Table 3. Correlation Matrix for Canadian FOAD

| Amerindian | African | European | ACHQ | S-factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amerindian | – | ||||

| African | –.221 | – | |||

| European | –.982 | 0.032 | – | ||

| ACHQ | –.795 | 0.563 | 0.704 | – | |

| S-factor | –.671 | –.119 | 0.71 | 0.657 | – |

| HDI | –.640 | 0.489 | 0.56 | 0.827 | 0.576 |

The provincial-level results also replicate at the subprovincial level at least when using education attainment as an outcome. For example, Statistics Canada reports college attendance rates for 293 municipalities. These rates correlate at –.40 with Amerindian ancestry and at –.41 with Aboriginal self-identified race/ethnicity (SIRE). Since data are available for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations, it can be demonstrated mathematically that the observed correlations are driven by an Indigenous-specific effect, rather than by other factors varying between municipalities. Data attached.

Overall, despite Canada’s rapid demographic change, regional variation in outcomes continues to reflect performance differences between historical groups—namely, Aboriginal and European Canadians.

References

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (n.d.). OECD Regional Well-Being. https://www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org

Putterman, L., & Weil, D. N. (2010). Post-1500 population flows and the long-run determinants of economic growth and inequality. The Quarterly journal of economics, 125(4), 1627-1682.

Smits, J. and Permanyer, I. The Subnational Human Development Database. Sci. Data. 6:190038 https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2019.38 (2019).

OECD Regional Well-Being

Canada is rapidly diversifying as a result of relaxed immigration policies. According to the 2021 Census, individuals of European ancestry now constitute approximately 67% of the population, down from 83% two decades earlier. The largest non-European groups include East Asians (9%), South Asians (7%), Aboriginal peoples (6%), and Black Canadians (4%). The pace of demographic change has outstripped genetic survey estimates. For instance, Ancestry.com still reported over 90% European ancestry in Canada as recently as 2017, whereas the true proportion is now likely under 70%. Despite this shift, geographic variation in socioeconomic and cognitive outcomes continues to correlate strongly with European and Amerindian ancestry proportions. This post provides an overview of Aboriginal demographic distributions and cognitive performance in Canada.

Aboriginal Populations: Geographic Distribution

Canada’s Aboriginal populations includes three officially recognized groups: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. Most First Nations and Métis individuals reside in the ten provinces, with roughly 40% of First Nations people living on reserves. By contrast, the Inuit are primarily concentrated in the three territories, especially Nunavut. Outside Nunavut, major Inuit populations are found in Newfoundland and Labrador (~7,000) and the Northwest Territories (~4,000).

Table 1. Geographic distribution of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians

| Region | Total Population | First Nations | Métis | Inuit | Total Aboriginal | Non-aboriginal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provinces | 36,873,821 | 1,144,065 | 586,900 | 17,015 | 1,747,980 | 35,125,841 |

| • Reservations | ~428,000 | ~428,000 | ~0 | ~0 | ~428,000 | ~0 |

| Territories | 118,160 | 19,430 | 4,290 | 53,530 | 77,250 | 40,910 |

| • Yukon | 40,232 | 6,935 | 1,285 | 260 | 8,805 | 31,427 |

| • Northwest Territories | 41,070 | 12,315 | 2,890 | 4,155 | 19,360 | 21,710 |

| • Nunavut | 36,858 | 180 | 115 | 49,115 | 49,410 | 7,448 |

| Canada Total | 36,991,981 | 1,163,495 | 591,190 | 70,545 | 1,807,250 | 35,184,731 |

Genetic Admixture of Aboriginal Populations

Admixture estimates for the Métis are sparse in the academic literature, but informal data from 23andMe (e.g., r/23andme subreddit) suggest approximately 65% European and 35% Amerindian ancestry, using the East Asian component as a proxy for Amerindian.

Figure 1. 23andMe admixture “donuts” for Métis individuals

First Nations individuals on reserves show average ancestry estimates of ~25% European and ~75% Amerindian, based on samples compiled from Flegontov et al. (2019), Reich et al. (2012), and Verdu et al. (2014). Off-reserve First Nations likely have higher European admixture. For Inuit, Zhou et al. (2019) report about 5% European admixture among the Nunavik Inuit of Arctic Quebec. Greenlandic Inuit, by contrast, average about 25% European ancestry, though this is lower in eastern Greenland near Nunavut. For context, Moreau et al. (2013) report ~2% Amerindian admixture in the French Canadian population. Estimated admixture — this are admittedly rough estimates –is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Estimated admixture for White/European Canadians and Indigenous groups

| European % | Amerindian % | ||

| European Canadians | 0.98 | 0.02 | |

| Metis | 0.65 | 0.35 | |

| First Nations | 0.25 | 0.75 | |

| Inuit | 0.05 | 0.95 | |

Academic Achievement Gaps

In other posts, we have discussed the aptitude test scores of various ethnic groups. Given Canada’s rapidly changing population, it is difficult to keep pace. Regarding Aboriginal populations specifically, most academic achievement data in Canada pertain to off-reservation individuals residing in the ten provinces. This means the Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut are typically excluded. Approximately 40% of Aboriginal students live either on a reserve or in one of the territories, resulting in a substantial portion of the Aboriginal population—particularly First Nations and Inuit—not being represented in these datasets.

The most comprehensive data available for off-reserve Aboriginal students in the provinces come from the Pan-Canadian Assessment Program (PCAP), which evaluates the academic performance of 8th-grade students every three years. Administered by the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), PCAP publishes contextual reports for each assessment cycle, focusing on a specific domain (Mathematics, Reading, or Science). Mean scores are standardized with a total standard deviation (SD) of 100. Results from 2010 to 2019, converted into Cohen’s d values, are summarized in Table 3. Off-reserve First Nations and Inuit students perform approximately d = –0.55 to –0.60 below the non-Aboriginal mean, while Métis and individuals of mixed Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal ancestry—who likely have similar levels of European ancestry—score around d = –0.30 below non-Aboriginals.

Table 3. Achievement gaps (Cohen’s d) on PCAP tests

| Metis | Mixed aborig. / not | First Nations | Multiple aborig. | Inuit | |

| Math 2010 | 0.4 | 0.54 | 0.62 | ||

| Science 2013 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.84 | ||

| Reading 2016 | 0.23 | 0.56 | 0.31 | ||

| Math 2019 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.42 |

| Average | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.55 |

These performance patterns are also evident at the provincial level. While most provinces do not disaggregate achievement data by specific Aboriginal groups, Ontario is an exception. The Government of Ontario (n.d.) reports pass rates—defined as achieving Level 3 or 4—on provincial Mathematics and Reading assessments (EQAO). Table 4 presents these pass rates converted into Cohen’s d scores, assuming a normal distribution. Métis and First Nations students perform similarly to the results observed in the PCAP data. Because the vast majority of Métis reside in the provinces and outside of reserves, the available achievement data are broadly representative of Métis performance.

Table 4. Test score gaps between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students in Ontario (Cohen’s d, EQAO assessments)

| Metis | First Nations | Inuit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | N | d | N | d | N | d | ||

| Math_2011 | 337 | 0.33 | 1399 | 0.7 | ||||

| Math_2012 | 409 | 0.3 | 1549 | 0.7 | ||||

| Math_2013 | 454 | 0.3 | 1760 | 0.62 | 47 | 0.18 | ||

| Math_2015 | 536 | 0.39 | 1994 | 0.67 | 69 | 0.39 | ||

| Reading_2011 | 337 | 0.26 | 1399 | 0.6 | 24 | 0.57 | ||

| Reading_2012 | 409 | 0.19 | 1551 | 0.61 | 28 | 0.46 | ||

| Reading_2013 | 454 | 0.13 | 1759 | 0.5 | 47 | 0.22 | ||

| Reading_2015 | 536 | 0.35 | 1995 | 0.57 | 69 | 0.75 | ||

| Ave. | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.44 |

Another valuable data source—particularly for adult populations—is the 2012 Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Summary scores from this dataset, as reported by the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC, n.d.), include participants from all three territories, thereby capturing Inuit populations in Nunavut. However, the data remain limited to off-reservation individuals. A key advantage of the PIAAC dataset is its disaggregation of scores by whether the respondent’s mother tongue matches the language of the test (see Figure 2.12 for Literacy and Figure 2.13 for Numeracy). Table 5 summarizes comparisons between Aboriginal and non-aboriginal individuals whose mother tongue corresponds to the test language.

Table 5. Test score gaps (Cohen’s d) between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal individuals with matching test and mother tongue languages based on PIAAC 2012

| Metis | First Nations | Inuit | |

| N | 2025 | 2238 | 472 |

| d | d | d | |

| Literacy | 0.18 | 0.52 | 0.96 |

| Numeracy | 0.26 | 0.68 | 1.34 |

| Average | 0.22 | 0.6 | 1.15 |

The results suggest that differences are not simply due to linguistic bias since they show up among individuals who grew up speaking English or French. Adjusting for territorial distribution and on-reserve effects suggests Inuit, overall, score approximately d = 0.80 below non-aboriginals.

What about on reservations first nations? Bacic and Zheng (2024) report that on-reserve Indigenous students in British Columbia score approximately d = 0.38 below their off-reserve counterparts. Similarly, the Government of Ontario (n.d.) indicates that during the 2013–14 school year, only 19% of on-reserve Indigenous students met acceptable standards in mathematics, and 26.5% did so in reading. Based on the EQAO pass rate data used for Table 4, these figures correspond to an average performance roughly d = 0.64 below that of off-reserve Indigenous students—who themselves scored d = 0.62 below the non-Indigenous average. Taken together, these findings suggest that on-reserve First Nations students perform approximately one standard deviation below the non-Indigenous mean. Averaging across on- and off-reserve populations, the total First Nations population appears to score around d = 0.80 below the non-Indigenous population.

IQ Test Scores

For the Admixture in the Americas update, our primary focus is on achievement test scores. Nonetheless, it is worth revisiting IQ-based findings, particularly as only a handful of studies published in the 21st century have reported IQ data for Indigenous populations in Canada.

Inuit Populations

Two notable studies examine Inuit samples in Arctic Quebec. Jacobson et al. (2014) report a mean IQ of 91.8 among 282 Inuit children, based on a culturally adapted version of the U.S. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC). A consistent pattern—also observed in First Nations populations—is evident: relatively higher performance on spatial subtests and lower scores on verbal comprehension, processing speed, and working memory.

Plusquellec et al. (2007) provide corresponding data for the mothers of these children (N = 165–169). On the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), the mothers averaged 68.2. On Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (SPM), they scored an average of 34.7 raw. Because these women fell outside the SPM age norms, the raw score was converted using the Advanced Progressive Matrices (APM) norms using Becker’s (2023) tables. The corresponding APM score of 5.15 (rounded down to 5) for a mean age of 24.9 (rounded up to 25) yields an estimated IQ of 65.84. Applying a Flynn Effect correction (to the converted APM-based score) reduces this by an additional 3.99 points. Additionally, Faucher (1999) reported an average SPM score of 35.9 for 44 Inuit adults (mean age = 24.6) from Nunavik. This corresponds to an APM score of 6.02, which is equivalent to an IQ of 68.27 when rounded to age 25. Applying a Flynn Effect correction reduces this by 4.20 points.

Due to the heterogeneity across tests and the assumptions involved in converting SPM raw scores to standardized scores, we refrain from calculating a combined average. For broader context, Lynn (2016) reports a mean IQ of 91 for Arctic populations across Alaska, Canada, and Russia. The key point for our analysis is that both IQ and achievement scores for Inuit populations are comparatively low.

First Nations Populations

We identified nine 21st-century studies reporting IQ data across 11 First Nations samples:

-

Diaz (2005): WAIS-III Matrix Reasoning score of 9.02 for 42 on-reserve adults in British Columbia. Assuming this is a scaled subtest score (M = 10, SD = 3), this corresponds to an IQ of 95.1.

-

Morin (2006): Average IQ of 91.49 for 49 children on a Saskatchewan reserve, using the Das–Naglieri Cognitive Assessment System (CAS), a test specifically designed to be less culturally biased.

-

Root (2006): Root (2006) reported SPM scores on Forms A–D of 33.16 (N = 38) for students who later dropped out and 38.34 (N = 25) for those who graduated. According to Becker (personal communication, May 8, 2025), the conversion equation to the full form (A–E) is:

SPM_RS(A–E) = 0.0133 × [SPM_RS(A–D)]² + 0.4547 × [SPM_RS(A–D)] + 5.7301.

Applying this formula yields estimated raw scores of 35.43 and 42.71, respectively. Using Becker’s (2023) norms and an estimated age of 13.5, the corresponding IQ equivalents are 81.26 and 93.80. Adjusting for the Flynn Effect reduces each score by 3.99 points. -

Vanderpool & Catano (2008): Among 101 young adults (ages 18–28), CFAT = 87, SPM = 96, along with Mill Hill Vocabulary and Wonderlic scores. Differential item functioning analyses showed minimal cultural bias. Spatial abilities were comparable to the general military recruit population.

-

Dela Cruz & McCarthy (2010): PPVT-IV mean of 98.3 for 44 off-reserve children in Alberta Head Start.

-

Vicaire (2011): An average SPM score of 36.66 on Forms A–D was reported for 53 children in remote First Nations schools. Using the conversion formula referenced in relation to Root (2006), this corresponds to a full-form (A–E) raw score of 40.27. Based on Becker’s (2023) tables and an estimated age of 14, the corresponding IQ is 88.61. Applying a Flynn Effect correction reduces this by 6.09 points.

-

Janzen et al. (2013): CAS scores of 86.32 (N = 84, Alberta) and 91.49 (N = 49, Saskatchewan).

-

Babcock (2017): WISC-IV mean of 94.96 for 60 off-reserve First Nations children, compared to 100.6 for White children in the standardization sample.

-

Hanson (2019): WISC-IV mean of 78.56 for 102 First Nations children in the Northwest Territories. Subtest analysis showed relatively strong visual-spatial performance and weaker verbal scores.

Excluding the Diaz (2005) result and averaging across the remaining ten samples (with multiple test scores averaged for Vanderpool & Catano (2008), the unadjusted weighted mean IQ for 21st century First Nations individuals is approximately 88.47. Applying Flynn Effect corrections would lower this by one to two points. Lynn (2016), analyzing five Canadian studies from 1968–1987, reports a similar average of 85.2. While individual conversions may be debated, Lynn’s overall estimate appears broadly accurate. Most of these studies focus on individuals living on reserves, which aligns with achievement data indicating performance approximately one standard deviation below the non-Indigenous mean. The average for the broader First Nations population—especially off-reserve individuals—would likely be somewhat higher.

Thus, in this case, IQ test results align closely with academic achievement outcomes. For both First Nations and Inuit populations, scores are consistently lower than those of the non-aboriginal population. IQ test results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. IQ results across studies.

| Author | Test | N | FSIQ M | Flynn corrected FSIQ | Verbal | Spatial | Fluid | Working Memory | Processing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diaz (2005) | Martix subtest, WAIS-III | Native American | Califonia, LA | 64 | 98.35 | |||||||

| Martix subtest, WAIS-III | Native American | British Columbia reserves | 42 | 95.1 | ||||||||

| Morin (2006) | CAS | First Nations | Saskatchewan reserve | 49 | 91.49 | No | ||||||

| Root (2006) | SPM | First Nations | Quebec reserve U | 38 | 81.26 | 77.27 | ||||||

| Root (2006) | SPM | First Nations | Quebec reserve A | 25 | 93.80 | 89.81 | ||||||

| Vanderpool & Catano (2008) | First Nations | remote Manitoba | 101 | |||||||||

| CFAT | 87 | No | 89 | 95 | ||||||||

| SPM | 96 | No | 42 | |||||||||

| MHV | 91 | No | 28 | |||||||||

| Wonderlic | 88 | No | ||||||||||

| General population Recruits | 108 | |||||||||||

| CFAT | 104 | No | 104 | 99 | ||||||||

| SPM | 101 | No | ||||||||||

| MHV | 100 | No | ||||||||||

| Wonderlic | 106 | No | ||||||||||

| dela Cruz & McCarthy (2010) | PPVT-IV | Aboriginal | Alberta off reseve | 44 | 98.3 | No | ||||||

| Vicaire (2011) | SPM | First Nations | remote schools | 53 | 88.61 | 82.52 | ||||||

| Janzen et al. (2013) | CAS | Native Children | Alberta reserve | 84 | 86.32 | No | ||||||

| Janzen et al. (2013) | CAS | Native Children | Saskatchean reserve | 49 | 91.49 | No | ||||||

| Babcock (2017) | WISC-IV CAN | |||||||||||

| Asian | 96 | 102.34 | No | |||||||||

| Caucasian | 647 | 100.6 | No | |||||||||

| First Nation | Off reservation | 60 | 94.98 | No | ||||||||

| Other | 77 | 95.92 | No | |||||||||

| Hanson (2019) | WISC-IV CAN | First Nations | Northwest territories | 102 | 78.56 | No | 77.47 | 93.21 | 86.01 | 80.97 | 84.34 | |

| Faucher (1999) | SPM | Inuit | Nunavik | 44 | 68.27 | 64.07 | ||||||

| Plusquellec et al. (2007) | Inuit | Arctic Québec | 165-169 | |||||||||

| PPVT USA | 68.2 | No | ||||||||||

| SPM | 65.84 | 61.85 | 34.7 | |||||||||

| Jacobson et al. (2014) | WISC-IV USA, Inuit adapted | Inuit | Arctic Québec | 282 | 91.8 | No | 84.5 | 94.2 | 89.5 | 86.6 | ||

Conclusion

In Canada, both achievement and IQ tests consistently reveal cognitive disparities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations, particularly among First Nations and Inuit. These differences are observed nationwide and within provinces & territories and persist even when matching on language. Given the markedly uneven regional distribution of Aboriginal populations across Canada, we can reasonably expect that Amerindian ancestry will be negatively correlated with both cognitive ability and socioeconomic status across Canadian regions. In Part 2, we examine whether this prediction holds.

References

Babcock, S. E. (2017). Examining the influence of demographic differences on children’s WISC-V test performance: A Canadian perspective [Master’s thesis, University of Western Ontario].

Bacic, R., & Zheng, A. (2024). Race and the income‐achievement gap. Economic Inquiry, 62(1), 5–23.

Becker, D. (2023, October 25). National IQ dataset (Version 1.3.5) [Dataset].

Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), & Indigenous Services Canada (ISC). (n.d.). Adult competencies among Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Findings from the first cycle of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). Government of Canada.

Dela Cruz, A. M., & McCarthy, P. (2010). Alberta Aboriginal Head Start in urban and northern communities: Longitudinal study pilot phase. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 30(2).

Diaz, S. H. (2005). Differences in cognitive strengths between Native North Americans living in rural versus urban environments [Doctoral dissertation, Fielding Graduate University].

Faucher, C. (2002). Étude des associations entre le développement cognitif et la qualité de l’environnement familial dans la population inuit du Nunavik. National Library of Canada= Bibliothèque nationale du Canada, Ottawa.

Flegontov, P., Altınışık, N. E., Changmai, P., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Adamski, N., … & Schiffels, S. (2019). Palaeo-Eskimo genetic ancestry and the peopling of Chukotka and North America. Nature, 570(7760), 236–240.

Government of Ontario. (n.d.). Strengthening our learning journey: Third progress report on the implementation of the Ontario First Nation, Métis and Inuit education policy framework.

Hanson, J. (2019). Exploratory factor analysis of the Canadian Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—for a sample of First Nations students [Master’s thesis, Eastern Illinois University].

Jacobson, J. L., Muckle, G., Ayotte, P., Dewailly, É., & Jacobson, S. W. (2015). Relation of prenatal methylmercury exposure from environmental sources to childhood IQ. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123(8), 827–833.

Janzen, T. M., Saklofske, D. H., & Das, J. P. (2013). Cognitive and reading profiles of two samples of Canadian First Nations children: Comparing two models for identifying reading disability. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(4), 323–344.

Lynn, R. (2016). Race differences in intelligence: An evolutionary analysis (2nd rev. ed.). Washington Summit Publishers.

Moltke, I., Fumagalli, M., Korneliussen, T. S., Crawford, J. E., Bjerregaard, P., Jørgensen, M. E., … & Albrechtsen, A. (2015). Uncovering the genetic history of the present-day Greenlandic population. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 96(1), 54–69.

Moreau, C., Lefebvre, J. F., Jomphe, M., Bhérer, C., Ruiz-Linares, A., Vézina, H., … & Labuda, D. (2013). Native American admixture in the Quebec founder population. PLOS ONE, 8(6), e65507.

Morin, T. L. (2006). A cognitive approach to word-reading for First Nations children [Master’s thesis, University of Saskatchewan].

Plusquellec, P., Muckle, G., Dewailly, É., Ayotte, P., Jacobson, S. W., & Jacobson, J. L. (2007). The relation of low-level prenatal lead exposure to behavioral indicators of attention in Inuit infants in Arctic Quebec. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 29(5), 527–537.

Reich, D., Patterson, N., Campbell, D., Tandon, A., Mazieres, S., … & Bustamante, C. D. (2012). Reconstructing Native American population history. Nature, 488(7411), 370–374.

Root, R. (2008). Predictors of educational attainment among Naskapi adolescents [Doctoral dissertation, McGill University].

Vanderpool, M., & Catano, V. M. (2008). Comparing the performance of Native North Americans and predominantly White military recruits on verbal and nonverbal measures of cognitive ability. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 16(3), 239–248.

Verdu, P., Pemberton, T. J., Laurent, R., Kemp, B. M., Gonzalez-Oliver, A., Gorodezky, C., … & Malhi, R. S. (2014). Patterns of admixture and population structure in native populations of Northwest North America. PLOS Genetics, 10(8), e1004530.

Vicaire, M. (2011). Cultural identity, intelligence, and self-esteem: Towards enriching the understanding of academic outcomes in a community of First Nation students [Master’s thesis, McGill University].

Zhou, S., Xie, P., Quoibion, A., Ambalavanan, A., Dionne-Laporte, A., Spiegelman, D., … & Rouleau, G. A. (2019). Genetic architecture and adaptations of Nunavik Inuit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(32), 16012–16017.

]]>

Less is known about the performance of more recent immigrant-origin groups, as academic performance data disaggregated by race/ethnicity is generally not collected at the national level in Canada. However, relatively high academic performance among Chinese and other Northeast Asian Canadians has been documented since Peter Sandiford’s research on Vancouver’s Chinese population in the 1920s (Sandiford & Kerr, 1926), with further evidence summarized by Vernon (1982). More recent national and provincial achievement data corroborate these findings (Bacic & Zheng, 2024; Barber et al., 2021). By contrast, average performance among other ethnic groups—such as Asian Indians, Filipinos, and Hispanics—remains less clear. The same applies to the children of Black African immigrants, many of whom come from highly selected backgrounds — and whom are highly educated. While I have previously reported ethnic performance data from the Toronto District School Board, these findings should not be assumed to generalize nationally or even across Ontario.

Recently, I was able to compile a decade’s worth of Canadian Advanced Placement (AP) data, as reported by College Board (years: 2009, 2011–2019) and to convert AP threshold pass rates into d-scores using the method of thresholds. Unfortunately, post-George Floyd, College Board changed its policy and ceased reporting Canadian scores by race/ethnicity; as a result, data after 2019 is not available.

Note, for these analyses, I dropped the three studio art scores along with all of the ‘language & culture’ scores, as Warne (2016) found that these tests had low correlations with PSAT scores. (Both the original and modified datafiles are attached; thus if readers wish they can modify the analyses as desired.) Moreover, I computed d-values with respect to the total mean; since Asians score higher, self-identifying White Canadians scored below average. Additionally, I dropped the American Indian group since there were too few individuals to allow for reliable estimates. While Hispanic/Latino is a “visible minority” group in Canada, the number reporting as Hispanic in the Canadian AP datasets seems excessive. This group may include Iberians in addition to Latin Americans.

Summary results are presented below, with the final row reporting weighted-average ACHQ scores. Unlike in the United States, AP exams are not widely taken in Canada, so these results should be interpreted with caution — they represent a few more data points.

Table 1. Canadian 2009-2019 Advance Placement Results by Self-reported race/ethnicity

| Asian | Black | Hispanic | White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | d | N | d | N | d | N | d | |||

| 2019 | 14061 | 0.172 | 575 | -0.565 | 730 | -0.254 | 10516 | -0.180 | ||

| 2018 | 13282 | 0.181 | 504 | -0.385 | 557 | -0.285 | 10362 | -0.175 | ||

| 2017 | 12258 | 0.189 | 471 | -0.486 | 673 | -0.320 | 10856 | -0.146 | ||

| 2016 | 11291 | 0.172 | 519 | -0.490 | 590 | -0.330 | 10649 | -0.128 | ||

| 2015 | 10037 | 0.179 | 473 | -0.545 | 274 | -0.160 | 10359 | -0.094 | ||

| 2014 | 9619 | 0.221 | 440 | -0.584 | 286 | -0.240 | 10479 | -0.130 | ||

| 2013 | 9680 | 0.210 | 419 | -0.423 | 236 | -0.351 | 10901 | -0.135 | ||

| 2012 | 8887 | 0.213 | 380 | -0.584 | 188 | -0.277 | 10649 | -0.141 | ||

| 2011 | 8152 | 0.218 | 318 | -0.783 | 155 | -0.212 | 10920 | -0.125 | ||

| 2010 | 7172 | 0.233 | 204 | -0.794 | 202 | -0.094 | 10324 | -0.136 | ||

| 2009 | 6772 | 0.205 | 211 | -0.898 | 87 | -0.466 | 9602 | -0.126 | ||

| Ave d. | 0.196 | -0.557 | -0.275 | -0.138 | ||||||

| ACHQ M | 105.01 | 93.72 | 97.95 | 100.00 | ||||||

| N | 111211 | 4514 | 3978 | 115617 | ||||||

For comparison, Warne (2016) reports that, in the United States, the weighted mean AP group differences in 2015 were: d = 0.774 (White–Black), d = 0.484 (White–Hispanic), and d = –0.156 (White–Asian). Thus, relative to the U.S., all non-White groups perform better on AP tests in Canada. For other national-level comparisons using Canadian datasets, see here. As I’ve previously argued, it would be worthwhile to collect more robust data on ethnic differences across a range of countries prior to hypothesizing about causes, rather than relying solely on U.S. data.

The R code and data files can be found here.

References

- Bacic, R., & Zheng, A. (2024). Race and the income‐achievement gap. Economic Inquiry, 62(1), 5–23.

- Barber, M., & Jones, M. E. (2021). Inequalities in test scores between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth in Canada. Economics of Education Review, 83, 102139.

- Sandiford, P., & Kerr, R. (1926). Intelligence of Chinese and Japanese children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 17(6), 361.

- Vernon, P., (1982). The abilities and achievements of orientals in North America. Academic Press.

- Warne, R. T. (2016). Testing Spearman’s hypothesis with Advanced Placement examination data. Intelligence, 57, 87–95.

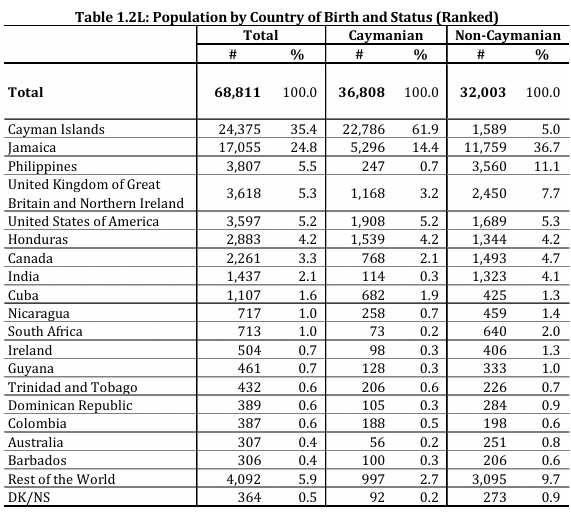

Figure 1. Population by Country of Birth for the Cayman Islands (2021)

The Cayman Islands government does not officially report race or ethnicity data, contrary to Wikipedia’s assertions. The 2008 CIA World Factbook estimates the racial composition as 40% Afro-European, 20% African, 20% European, and 20% “other,” but the basis for these figures is unclear, and their frequent citation lacks specificity.

Genetic ancestry data specific to the Cayman Islands is scarce. The only relevant study, Micheletti et al. (2020), analyzed 23andMe samples from 1,526 self-identified Black individuals from Jamaica and the Cayman Islands (not disaggregated). Participants were included if all four grandparents were born in the same country and reported historical ties to an African nation. The study found an average ancestry (corrected so to be out of 100%) of 78.89% African, 19.84% European, and 1.23% East Asian and Amerindian combined. Given Jamaica’s population (2.8 million) vastly exceeds the Cayman Islands’, most samples likely represent Jamaicans, limiting the study’s applicability to Caymanians.

To estimate Caymanian resident ancestry, we rely on several assumptions:

- Non-immigrant Caymanian residents (61.9% of the resident population) align with the CIA’s 2008 breakdown: 50% Afro-European, and 25% African, and 25% European.

- Black non-immigrant Caymanians born on the island have an ancestry profile similar to Jamaicans. Jamaican ancestry, based on four studies including Micheletti et al. (2020), is shown in Table 1. Except for Vergara et al. (2013), these studies focus on self-identified individuals of African descent. The 2011 Jamaican census shows 98.17% of Jamaicans identify as Black (92.11%) or mixed (6.06%), suggesting no need to adjust for non-Afro-descent groups (unlike Barbados or the Bahamas).

Table 1: Admixture estimates for Jamaica

| Ethnic group | N | Markers | European % | African % | Amerindian % | East Asian % | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afro-Caribbean | 119 | 15 STRs | 16 | 78.3 | 5.7 | Simms et al. (2010) | |

| Afro-Caribbean | 44 | 105 AIMs | 10.3 | 81.4 | 8.3 | Torres et al. (2013) | |

| General population | 706 | 237 AIMS | 14.00 | 76.00 | 9 | Vergara et al. (2013) | |

| Self-reported African ancestry | 45 | 551,510 SNPs | 11 | 89 | 1 | Mathias et al. (2016) | |

| Self-reported African ancestry | 1526 | 560,000 SNPs | 18.99 | 75.5 | 0.17 | 1.01 | Micheletti et al. (2020) |

| above corrected | 19.84 | 78.89 | 0.18 | 1.06 | Micheletti et al. (2020) | ||

| Average | 14.23 | 80.72 | 1.90 | 3.15 |

- White non-immigrant Caymanians resemble white British individuals (~100% European).

- Self-identified mixed-race non-immigrant Caymanians reflect an intermediate blend of African and European ancestry.

- Immigrants (38.1% of the resident population), mirror their countries’ average ancestry.

Weighting these groups by population share and ancestry profiles yields an approximate Cayman Islands average of 50% European, 40% African, 5% Amerindian, and 5% other (e.g., East Asian, South Asian). Without Cayman-specific genetic studies or detailed demographic data, this remains a rough estimate.

Turning to academic achievement, prior estimates suggested a CXC ACHQ of 85.41 and a GMATQ of 94.45 relative to the U.S. mean, averaging 89.48. However, these rely on selective samples (test-takers), limiting their representativeness.

Additional data from 2019-20, 2020-21, 2021-22, 2023-24 educational reports offer CAT4 scores for 1,543 Year 11 students in government schools, where most Cayman residents study (expatriates often attend private schools). These scores, (apparently) benchmarked against UK norms, yield a weighted mean of 92.88. This is much higher than the HVIQ of 74 estimated by Jason Malloy based on data from the middle of last century!

In this series, our focus is on ACHQ. For the academic years 2021-22 and 2023-24, the Department of Education has provided the Rising Stars assessment results for Year 6 students. Rising Stars is a UK-based assessment that aligns with the UK mean. Instead of reporting mean scores or percentages of students achieving basic levels, only the percentage of students performing at the level predicted by CAT4 is provided. However, with the application of clever statistical methods, it is possible to estimate the mean scores.

To illustrate, Figure 2 displays the 2023-24 attainment across Grammar, Punctuation, and Spelling (GAPS), Reading, and Mathematics relative to the predictions from the CAT4 test. To estimate the Academic Achievement Quotient (ACHQ), we consider 100% meeting expectations as equivalent to performing at the CAT4 mean. We express this relative to a normal curve by dividing the percentage meeting expectations by 2. For instance, in 2023, 81% met the GAPS predictions; halving this value (0.81/2 = 0.405) places it relative to a mean of 0.50 on a normal curve. Applying a normal curve transformation results in a difference of 0.24 (NORMSINV(0.50) – NORMSINV(0.405)) relative to the CAT mean. Averaging this difference across subjects and years gives a Cohen’s d of 0.37. With a CAT4 mean of 94.84 for the two years with Rising Stars data (UK-normed), we adjust by subtracting 0.37 *15 from the mean CAT4 for these years, resulting in 89.29. Since the UK ACHQ mean is 0.43 points above the U.S. mean, we add this difference to arrive at 89.72 (USA-normed).

Figure 2. Relative Performance on Rising Star versus CAT4 Assessments, 2023-24

Note: Figure from the 2023-24 government report showing Year 6 attainment in government schools, based on end-of-year school-based tests. Performance is measured as the percentage of students meeting CAT4-predicted levels (CAT4 Predictor), Rising Stars (RS), and Key Stage 2 SATs (KS2 SATS) across GAPS, Reading, Writing, and Mathematics.

This result aligns closely with our earlier estimate of 89.48, based on the average of CXC and GMAT scores. Thus, estimates derived from three different tests—normed against Caribbean, U.S., and UK populations—converge. We adopt an ACHQ of 89.37 as the current best estimate for the Cayman Islands. This is lower than the NIQ of 92.88 (for 2021 to 2023), which is consistent with governmental reports noting a discrepancy between these metrics. For example, in 2023 it is noted:

When the KS2 data is compared against both CAT4 predictors and Rising Stars estimates for this cohort, a consistent pattern emerged: students consistently lag behind their predicted or estimated levels across all areas. The striking aspect is the substantial variances mathematics: 56pp and 33pp for CAT4 and RS, respectively (See Figure 12). This underperformance may stem from gaps in foundational knowledge, insufficient practice opportunities, or potential misalignment between instructional approaches and the skills measured by these assessments.

We consider both NIQ and NACHQ to measure “national cognitive ability,” so one might average the two for a combined estimate. However, for consistency in this series, we rely on ACHQ.

In the context of the Admixture in Americans project, results from the Cayman Islands are of limited value due to uncertainties in ancestry and cognitive ability estimates, and, more significantly, the high proportion of recent immigrants, who cannot be assumed to represent their home populations.

References

Economic and Statistics Office. (2021). The Cayman Islands’ Human Development Index report 2021. Economic and Statistics Office.

Department of Education Services, Cayman Islands Government [DES]. (2021–2024). Data reports for academic years 2020–21 to 2023–24. Cayman Islands Government.

Mathias, R. A., Taub, M. A., Gignoux, C. R., Fu, W., Musharoff, S., O’Connor, T. D., … & Barnes, K. C. (2016). A continuum of admixture in the Western Hemisphere revealed by the African Diaspora genome. Nature communications, 7(1), 12522.

Micheletti, S. J., Bryc, K., Esselmann, S. G. A., Freyman, W. A., Moreno, M. E., Poznik, G. D., … & Mountain, J. L. (2020). Genetic consequences of the transatlantic slave trade in the Americas. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107(2), 265-277.

Simms, T. M., Rodriguez, C. E., Rodriguez, R., & Herrera, R. J. (2010). The genetic structure of populations from Haiti and Jamaica reflect divergent demographic histories. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 142(1), 49-66.

Torres, J. B., Stone, A. C., & Kittles, R. (2013). An anthropological genetic perspective on Creolization in the Anglophone Caribbean. American journal of physical anthropology, 151(1), 135-143.

Vergara, C., Murray, T., Rafaels, N., Lewis, R., Campbell, M., Foster, C., … & Barnes, K. C. (2013). African ancestry is a risk factor for asthma and high total IgE levels in African admixed populations. Genetic epidemiology, 37(4), 393-401.

]]>. . .

France governs three overseas departments in the Americas—French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique—along with three overseas American collectivities: Saint Barthélemy (St. Barth), Saint Martin, and Saint Pierre and Miquelon. The populations of these territories display a rich diversity of ancestries, making them an interesting case study.

Saint Pierre and Miquelon, located off the coast of Canada, has a population of approximately 5,819 and is the most European-influenced of France’s overseas territories. Its residents are primarily descendants of French settlers from Normandy, Brittany, and other regions, supplemented by recent migrants from metropolitan France. Saint Barthélemy, a small Caribbean island that separated from Guadeloupe in 2007, has a population of around 10,000. Although France does not officially collect ethnic or racial data, visual observations of children in local primary schools and at festivals suggest the population is roughly 80% of European ancestry (mostly French), 15% of African ancestry, and 5% of other origins. This aligns with historical settlement records, which indicate a majority of French descent.

Figure 1. School and Festival Pictures from St. Barts

Guadeloupe and Martinique are primarily inhabited by admixed Afro-European populations, with additional contributions from descendants of South Asian Indian groups. A 2019 study by Mendisco et al. analyzed mtDNA and Y-DNA haplogroups from individuals whose grandparents were all born in Guadeloupe, estimating ancestry proportions. Averaging these maternal and paternal markers suggests that Guadeloupe’s population is approximately 25.5% European, 69% African, 0.25% Amerindian, and 5.3% other (mostly South Asian). These estimates, which do not account for recent immigration, reflect higher African maternal ancestry and greater European paternal contributions, consistent with the region’s colonial history. Given Martinique’s similar historical trajectory, its ancestry composition is likely comparable, though slight variations may arise from local differences in settlement and immigration patterns.

Notably, island-wide studies on sickle cell anemia suggest that both Guadeloupe and Martinique have lower levels of African ancestry compared to Anglo-Caribbean countries such as Jamaica, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada, St. Lucia, and Tobago (Knight-Madden et al., 2019). As shown in Table 1, beta-S and beta-C gene frequencies—markers associated with African ancestry—are approximately 75% of the rates found in these other islands. Extrapolating from these figures suggests a somewhat lower African ancestry proportion of around 60%, since these other countries have around 80% African ancestry (when taking into account admixture in the respective Afro-Caribbean populations and the proportion of non-Afro-Caribbeans). However, due to the potential influence of genetic drift and selection on specific gene frequencies, the estimates based on Mendisco et al. (2019) remain the most reliable for these populations.

Table 1. Frequency Data on Sickle Cell-Related Alleles (β^S and β^C) by Country/Territory

| Country/Territory | β^S | β^C | β^S + β^C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jamaica | 0.055 | 0.019 | 0.074 |

| Guadeloupe | 0.042 | 0.012 | 0.054 |

| Martinique | 0.04 | 0.011 | 0.051 |

| French Guiana | 0.04 | 0.011 | 0.051 |

| Tobago | 0.051 | 0.02 | 0.071 |

| Grenada | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.071 |

| Saint Lucia | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.072 |

| Haiti | 0.062 | 0.012 | 0.074 |

| Saint Vincent & Grenadines | 0.055 | 0.015 | 0.07 |

| Cuba | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.014 |

Comprehensive admixture data for Saint Martin, a French overseas collectivity populated by admixed Afro-Caribbean groups, is limited. However, a study by Bera et al. (2001) examined HLA class I and II allele frequencies, revealing a population predominantly of African ancestry with a minor European component and no significant contributions from other groups. Based on this and comparisons with nearby islands like St. Kitts and Nevis, a rough estimate of Saint Martin’s ancestry might be approximately 80% African and 20% European, though this remains an approximation pending more detailed genetic analysis.

Figure 2. Festival Pictures from St. Martin

The majority of French Guiana’s population is comprised of recent immigrants and their descendants from countries such as Guyana, Suriname, Brazil, Haiti, China, Laos, Saint Lucia, and metropolitan France. The remainder includes Amerindians, Caribbean Creoles, and Maroons. Genetic studies suggest that the Maroons (Fortes-Lima et al., 2017), East Asians (Brucato et al., 2012), and Amerindians (Mazières et al., 2009) of this department exhibit little admixture. However, no genetic data is available for the Creole populations. Population admixture can be approximated by weighting ethnic or national groups according to their reported average ancestry; though official ethnic data is not collected in French Guiana various sources have reported estimates. The percentages provided, as detailed in Table 2, are plausible estimates.

Table 2: Admixture Estimates for French Guiana

| % Pop | African % | European % | Amerindian % | Other % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maroon | 15 | 98.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Creole | 25 | 80.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Amerindian | 3 | 0.68 | 9.56 | 89.76 | 0.00 |

| Guyana | 6 | 35.00 | 5.00 | 10.00 | 50.00 |

| Suriname | 12.5 | 40.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 50.00 |

| Brazilian | 9.3 | 19.60 | 68.10 | 11.60 | 0.00 |

| Haitian | 9.2 | 94.00 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Chinese | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| Laotian | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| St. Lucian | 3 | 71.67 | 18.22 | 7.22 | 2.90 |

| Metro. French | 12 | 2.83 | 87.20 | 0.00 | 9.97 |

| Weighted Ave. | 100 | 54.78 | 24.41 | 5.21 | 15.53 |

France is becoming increasingly less European in its demographic composition. Although ethnicity is not officially reported, detailed data on first- to third-generation immigrants by region of origin is available (INSEE, 2024). By combining this data with estimates of its overseas territories, admixture estimates can be derived for France as a whole. These estimates reveal a growing proportion of the population with North African and Middle Eastern ancestry, categorized here as “other.” The demographic shift, often described as the replacement of the indigenous French population, is substantially more pronounced among younger age groups, a trend partially obscured in overall population estimates. Admixture estimates for both France as a whole and its overseas departments and territories in the Americas are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Admixture Estimates for France and French American Possessions

| Country | Population | African % | European % | Amerindian % | Other % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France* | 68,373,647 | 4.97 | 84.67 | 0.00 | 10.36 |

| French Guiana | 292354 | 54.78 | 24.41 | 5.21 | 15.53 |

| Guadeloupe | 378561 | 69.00 | 25.50 | 0.25 | 5.30 |

| Martinique | 349,925 | 69.00 | 25.50 | 0.25 | 5.30 |

| St. Barth | 10,967 | 15.00 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 |

| St. Martin | 32489 | 80.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| St. Pierre et Miquelon | 5819 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

*Including overseas France; North Africans included as “Other.”

Since the 2017–2018 school year, France has administered yearly academic achievement tests to sixth and tenth graders, with assessments later expanded to other grades. The language test evaluates reading comprehension, oral language, spelling, grammar, and vocabulary, while the math test assesses knowledge of numbers, computation, problem-solving, geometry, and measurements. As of the time of writing, means and standard deviations were available for sixth-grade tests (2017–2023) and tenth-grade tests (2019–2024) for French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique.

Additionally, since 1998, the Journée Défense et Citoyenneté (JDC) has required citizens aged 16–25 to take language comprehension tests, which include tests of word recognition and passage comprehension. Percentages of individuals facing difficulties are reported by department. We converted these rates for 2014–15, 2018–19, 2019–20, and 2022–23 into d-scores. Data was available for French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. These test scores have been shown to correlate at r = .54 with a 66-item math test (Herrero et al., 2015). Although this correlation is substantially lower than the r = .85 found for PIAAC, it is relatively close to the r = .65 typically observed for academic achievement tests, such as the American NAEP tests.

Due to their smaller populations, data for Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Saint Barthélemy, and Saint Martin are less comprehensive, resulting in less precise estimates. Thus, for Saint Pierre and Miquelon, we additionally computed scores using all available data points, while for Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy, we calculated results additionally for grade 4. These findings are presented in Tables 4 and 5 below, respectively.

Table 4. Tests Scores for Saint Pierre & Miquelon

| Language | Math | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Grade | France | SP&M | France | SP&M | |||

| % Satisfactory | % Satisfactory | d | % Satisfactory | % Satisfactory | d | Ave. d | ||

| 2023 | Cours Préparatoire | 78.90 | 76.10 | 0.09 | 81.60 | 74.00 | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| 2023 | Cours Élémentaire 1 | 77.40 | 85.30 | -0.30 | 68.00 | 76.80 | -0.26 | -0.28 |

| 2023 | Cours Moyen 1 | 64.30 | 57.60 | 0.17 | 56.60 | 56.30 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| 2024 | Cours Moyen 2 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.09 | ||||

| 2019 | Middle school | -0.10 | -0.31 | -0.21 | ||||

| 2023 | Middle school | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 | ||||

| 2023 | Middle school | 52.90 | 44.80 | 0.20 | 47.10 | 41.90 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| 2019 | Middle school | -0.10 | -0.17 | -0.14 | ||||

| 2022 | Vocational School | 55.00 | 81.00 | -0.75 | 31.00 | 42.00 | -0.29 | -0.52 |

| 2022 | College Prep. | 92.00 | 95.00 | -0.24 | 77.00 | 84.00 | -0.26 | -0.25 |

Table 5. Test Scores for Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin

| Language | Math | Average | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d France / St. Martin | d France / St. Barts | d France / Martin | d France / St. Bars | d France / Martin | d France / St. Barts | d France / St. Barts | ||

| 6eme | 2019 | 0.94 | -0.06 | 1.16 | 0.36 | 1.05 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| 6eme | 2020 | 1.36 | -0.02 | 1.00 | -0.47 | 1.18 | -0.24 | -0.24 |

| 6eme | 2021 | 1.34 | -0.23 | 1.12 | -0.24 | 1.23 | -0.23 | -0.23 |

| 6eme | 2022 | 1.16 | 0.29 | 1.03 | 0.27 | 1.09 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| ave | 1.14 | -0.01 | -0.01 | |||||

| CE1 | 2019 | 0.95 | 0.15 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 0.80 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| CE1 | 2020 | 1.10 | -0.01 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| CE1 | 2021 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| CE1 | 2022 | 1.13 | -0.07 | 0.71 | -0.06 | 0.92 | -0.07 | -0.07 |

| ave | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |||||

| Grade 10 tech (LEGT R. Weinum & 2nde M. Choisy) | 2022 | 0.87 | 0.25 | 0.40 | -0.63 | 0.63 | -0.19 | -0.19 |

| Grade 10 prof (LP D. Jeffry & 2nde M. Choisy) | 2022 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.32 | -0.61 | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| ave | 0.64 | -0.04 | -0.04 |

For consistency, we rely on averages from sixth and tenth grades across these three collectivities, despite having only one year of tenth-grade data for Saint Martin, which was derived from a single school. For the overseas departments we averaged Grade 6, Grade 10, and the DofL test values. Results, alongside Human Development Index (HDI) and socioeconomic status (SES) data when available, are presented in Table 6 below. Academic achievement (ACHQ) and SES/HDI correlated strongly, with r-values ranging from .90 to .95, for regions with data. For the 13 Metropolitan French regions (that is, excluding overseas possessions) Grade 6 Math and Reading scores correlated at r = .69 with DofL scores, providing further support for the validity of the latter as measures of academic achievement.

Table 6. Test Scores, HDI, and S-factor for French Regions and Territories

| Region | Grade_6_ACH | Grade_10_ACH | DofL_ACH | ACH_ave | ACHQ | S-factor | HDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 99.28 | 0.886 | ||

| Auvergne-rhone-alpes | -0.101 | -0.142 | -0.121 | 101.10 | 0.727 | 0.881 | ||

| Bourgogne-franche-comte | -0.026 | 0.012 | -0.007 | 99.39 | 0.606 | 0.863 | ||

| Bretagne | -0.138 | -0.162 | -0.150 | 101.53 | 0.725 | 0.879 | ||

| Centre-val de loire | 0.008 | 0.039 | 0.024 | 98.93 | 0.683 | 0.865 | ||

| Corse | 0.059 | 0.210 | -0.112 | -0.026 | 99.68 | -0.17 | 0.843 | |

| Grand-est | -0.002 | -0.033 | -0.017 | 99.54 | 0.528 | 0.867 | ||

| Hauts-de-france | 0.137 | 0.036 | 0.087 | 97.98 | 0.294 | 0.852 | ||

| Ile-de-france | -0.069 | -0.147 | -0.108 | 100.90 | 0.708 | 0.93 | ||

| Normandie | 0.079 | 0.045 | 0.005 | 0.042 | 98.65 | 0.537 | 0.864 | |

| Nouvelle-aquitaine | -0.047 | -0.043 | -0.045 | 99.95 | 0.68 | 0.872 | ||

| Occitanie | -0.032 | -0.049 | -0.041 | 99.89 | 0.539 | 0.881 | ||

| Pays de la loire | -0.079 | -0.115 | -0.097 | 100.74 | 0.765 | 0.88 | ||

| Provence-alpes-cote d'azur | 0.004 | -0.090 | -0.043 | 99.92 | 0.391 | 0.883 | ||

| Guadeloupe | 0.460 | 0.565 | 0.700 | 0.575 | 90.66 | -1.194 | 0.841 | |

| French Guyane | 1.009 | 0.935 | 1.200 | 1.048 | 83.56 | -2.325 | 0.787 | |

| Martinique | 0.372 | 0.458 | 0.700 | 0.510 | 91.63 | -0.645 | 0.851 | |

| Mayotte | 1.496 | 1.589 | 1.800 | 1.628 | 74.86 | -2.176 | 0.764 | |

| La Reunion | 0.342 | 0.361 | 0.600 | 0.434 | 92.77 | -0.674 | 0.829 | |

| St-Pierre et Miquelon | -0.060 | -0.14 | -0.100 | 100.78 | ||||

| St. Martin | 1.140 | 0.64 | 0.890 | 85.93 | ||||

| St. Barthélemy | -0.01 | -0.04 | -0.025 | 99.66 |

Overseas departments and territories with less European influence tend to exhibit lower academic performance. This trend is holds when also considering the predominantly African population of Mayotte (Msaidie et al., 2011), the Afro-European-South Asian demographic mix of La Réunion (Berniell-Lee et al., 2008), and French Polynesia (not shown). However, the predominantly African Caribbean departments of Guadeloupe and Martinique demonstrate unexpectedly strong academic performance. The true ACHQ scores may even be higher insofar as JDC tests may be linguistically biased. However, that Guadeloupéens and Martiniquais do relatively better on the grade 6 and 10 language tests, which include an oral comprehension test, than the math tests would argue against linguistic bias. However, formal testing would be required to conclusively rule out any such bias.

While this analysis primarily focuses on achievement tests, findings from a study on IQ in the Guadeloupe population present a more complex picture. Oulhote et al. (2023) reported Raven’s Matrices scores for mothers and French-WISC scores for children from the TIMOUN mother-child cohort in Guadeloupe. The study involved 1,068 pregnant women recruited from the general population between November 2004 and December 2007, with a follow-up seven years later. Among the 569 children aged 7-8, the average WISC-IV score was 87.1 relative to the French mean. The 541 mothers achieved an average Standard Progressive Matrices (SPM) score of 35.4, equivalent to an Advanced Progressive Matrices (APM) score of 5.62 and an IQ of 70.79 based on British 1992 norms. Adjusted for the Flynn effect, this drops to 67.43. Averaging these scores yields a HVGIQ of 77 for Guadeloupe, which would need to be adjusted upwards a few points to align with U.S. metrics.

Jason Malloy also reported a low Raven’s Matrices score (IQ = 77, relative to the UK mean) for Guadeloupe, based on Massina et al. (2000). However, the Raven’s IQ scores are inconsistent with achievement test data, suggesting they may not accurately reflect the general cognitive ability of the population. Regardless, this series emphasizes academic achievement, which may diverge from nonverbal intelligence measures due to variations in schooling quality. This is evident in cases like Argentina, where achievement test scores are over 15 points lower than intelligence test scores.

Datafile, with sources.

References

Bera, O., Cesaire, R., Quelvennec, E., Quillivic, F., De Chavigny, V., Ribal, C., & Semana, G. (2001). HLA class I and class II allele and haplotype diversity in Martinicans. Tissue Antigens, 57(3), 200-207.

Berniell‐Lee, G., Plaza, S., Bosch, E., Calafell, F., Jourdan, E., Cesari, M., … & Comas, D. (2008). Admixture and sexual bias in the population settlement of La Reunion Island (Indian Ocean). American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 136(1), 100-107.

Brucato, N., Mazières, S., Guitard, E., Giscard, P. H., Bois, E., Larrouy, G., & Dugoujon, J. M. (2012). The Hmong diaspora: preserved south-east Asian genetic ancestry in French Guianese Asians. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 335(10-11), 698-707.

Dubut, V., Murail, P., Pech, N., Thionville, M. D., & Cartault, F. (2009). Inter‐and Extra‐Indian Admixture and Genetic Diversity in Reunion Island Revealed by Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA. Annals of Human Genetics, 73(3), 314-334.

Fortes-Lima, C., Gessain, A., Ruiz-Linares, A., Bortolini, M. C., Migot-Nabias, F., Bellis, G., … & Dugoujon, J. M. (2017). Genome-wide ancestry and demographic history of African-descendant Maroon communities from French Guiana and Suriname. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 101(5), 725-736.

Herrero, S., Huguet, T., & Vourc’h, R. (2015). Evaluation des compétences des jeunes en numératie lors de la JDC.[Assessing the numeracy skills of young adults during the JDC]. Educations Et Formations, 86, 259-282.

Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques. (2024). La diversité des origines et la mixité des unions progressent au fil des générations. INSEE. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6468640

Knight-Madden, J., Lee, K., Elana, G., Elenga, N., Marcheco-Teruel, B., Keshi, N., … & Hardy-Dessources, M. D. (2019). Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in the Caribbean: an update of the present situation and of the disease prevalence. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 5(1), 5.

Malloy, J. (2014, July 16). HVGIQ: Guadeloupe. Human Varieties. https://web.archive.org/web/20140724072218/https:/humanvarieties.org/2014/07/16/hvgiq-guadeloupe/

Massina, C., Le Gall, D., Aubin, G., Mazaux, J.M., Galanthe, E., Sainte-Foie, S., & Emile, J. (2000). Une observation de la récupération différentielle des deux langues chez une patiente aphasique bilingue français-créole guadeloupéen. Annales de Réadaptation et de Médecine Physique, 43, 450-464.

Mazieres, S., Callegari-Jacques, S. M., Crossetti, S. G., Dugoujon, J. M., Larrouy, G., Bois, E., … & Salzano, F. M. (2011). French Guiana Amerindian demographic history as revealed by autosomal and Y-chromosome STRs. Annals of Human Biology, 38(1), 76-83.

Mendisco, F., Pemonge, M. H., Romon, T., Lafleur, G., Richard, G., Courtaud, P., & Deguilloux, M. F. (2019). Tracing the genetic legacy in the French Caribbean islands: a study of mitochondrial and Y‐chromosome lineages in the Guadeloupe archipelago. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 170(4), 507-518.

Msaidie, S., Ducourneau, A., Boetsch, G., Longepied, G., Papa, K., Allibert, C., … & Mitchell, M. J. (2011). Genetic diversity on the Comoros Islands shows early seafaring as major determinant of human biocultural evolution in the Western Indian Ocean. European Journal of Human Genetics, 19(1), 89-94.

Oulhote, Y., Rouget, F., Michineau, L., Monfort, C., Desrochers-Couture, M., Thomé, J. P., … & Muckle, G. (2023). Prenatal and childhood chlordecone exposure, cognitive abilities and problem behaviors in 7-year-old children: the TIMOUN mother–child cohort in Guadeloupe. Environmental Health, 22(1), 21.

]]>Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is a predominantly Spanish-speaking U.S. territory. Its residents have full citizenship—allowing free movement to the mainland. Currently, more Puerto Ricans live on the mainland (5.8 million in 2023) than on the island (3.2 million). Based on the average of 16 samples, individuals on the island of Puerto Rico have an average European, African, and Amerindian ancestry of 66.67%, 19.80%, and 13.53%, respectively. The samples are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Admixture Estimates for Puerto Rico

| N | Markers | European % | African % | Amerindian % | Total % | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 181 | 44 AIMs | 65.5 | 16.2 | 18.3 | 100 | Salari et al. (2005) |

| 135 | 44 AIMs | 60.2 | 20.2 | 19.6 | 100 | Choudhry et al. (2006) |

| 223 | 104 AIMs | 62.7 | 22.8 | 14.6 | 100.1 | Risch et al. (2009) |

| 310 | 12 AIMs | 69.89 | 24.45 | 5.66 | 100 | Erdei et al. (2011) |

| 642 | 93 AIMs | 63.7 | 21.2 | 15.2 | 100.1 | Via et al. (2011) |

| 133 | 99 AIMs | 70 | 19 | 11 | 100 | Avena et al. (2012) |

| 803 | genome-wide | 67 | 20.6 | 12.4 | 100 | Galanter et al. (2012) |

| 55 | genome-wide | 72.4 | 14.8 | 12.8 | 100 | Gravel et al. (2013) |

| 65 | 20 | 12 | 97 | Vilar (2014) | ||

| 70 | 250800 markers | 78.31 | 12 | 9.68 | 99.99 | Montinaro et al. (2015) |

| 26 | 250800 markers | 69.73 | 21.37 | 8.92 | 100.02 | Montinaro et al. (2015) |

| 53 | genome-wide | 61 | 27 | 12 | 100 | Mathias et al. (2016) |

| 104 | genome-wide | 73.2 | 13.9 | 12.9 | 100 | Martin et al. (2017) |

| 415 | 100 AIMs | 64 | 21 | 15 | 100 | Irizarry‐Ramírez et al. (2017) |

| 425 | 105 AIMs | 61 | 21.1 | 18 | 100.1 | Pérez-Mayoral et al. (2019) |

| 409 | 105 AIMs | 61.3 | 20.7 | 18 | 100 | Pérez-Mayoral et al. (2020) |

| Simple Ave. | 66.56 | 19.77 | 13.5 | 99.83 | ||

| Corrected Ave. | 66.67 | 19.8 | 13.53 | 100 |