| CARVIEW |

Introduction

This is what I have to say, which of course is something important. As you can see we can use headings and other formatting in our work.

Al-Andalus was an area of the Iberian Peninsula that the Muslim-ruled and it was conquest .The story is that in the year 711, an oppressed Christian chief, Julian, went to Musa ibn Nusair, the governor of North Africa, with a plea for help against the tyrannical Visigoth ruler of Spain, Roderick. In the text book {Medieval Iberia: readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish sources, 2nd edition: edited by; Olivia Remie Constable} there a two primary source about the conquest of al-Andalus by Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam narrative of the conquest of al-Andualus and Ibn al-Qutiyya history of the conquest and both have different narration to tell and different dates of when things happened and how they saw them. Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam’s moralization tales of the conquest of al-Andalus offer a telling glimpse into the world of mainstream, pious Muslims as they reflected on Islam’s experience of conquest and we got to understand that his writing are typical of the Islamic culture of his time, also historians in recent decades have tended to discount the usefulness of Ibn “Abd al-Hakam and accounts likw for he study of the Islamic conquest of Spain. some have doubted whether many of the persons mentioned, such as Julian and Taria, even existed {Medieval Iberia: readings from Christian, Muslim, Jewish sources, 2nd edition: edited by; Olivia Remie Constable}. How he saw things from his own perspectives and the way he understood things is different from Ibn al-Qutiyya who was an Andalusi author and is said to have been a descendent of Sara, the granddaughter of the last Visigothic king, Witiza (Ibn al-Qutiyya’s name means “the son of the Gothic woman” ).There are also some persons mentioned and it is hard to know for a fact if they even existed or it was just the way he understood things. Ibn al-Qutiya was said to be a descendant of Sera and his narration contained elements not found in other sources or accounts but doesn’t mean his narration of the history of al-Andalus conquest is the real story cause he also had his own view and perspective of things and although Ibn al-Hakam provided one of the earliest accounts of the conquest of 711, he was writing far away in the eastern Islamic world {Medieval Iberia: readings from Christian, Muslim, Jewish sources, 2nd edition; edited by: Olivia Remie Constable}. Ibn al-Qutiyya’s narration was written long after the conquest that it describes, and it contains element not found in other accounts.however, these may record family traditins and reflect an Andalusi perspective of events although Ibn “Abd al-Hakam provides one of the earliest accounts of the conquest of 711, he was writing far away in the Eastern Islamic world {Medieval Iberia: readings from Chistian, Muslim, Jewish sources, 2nd edition: edited by; Olivia Remie Constable}. They both have different experience and perspective of when meeting Tariq, Musa and the other Muslim kings, also Ibn al-Hakam talks about a slave girl according to him name Umm Hakim in Tariq and An island off the coast of the Southern Spain captured by Tariq which is also said to be named after her as Wadi Umm Hakim, he also shared his account with various stories in which Musa, Tariq, and members of the caliphal family in Syria quarrel and intrigue over sharing the vast spoils from al-Andalus.

The secondary source is from (Dahm, Murray. “The Other Side) about how the Arabic sources, when addressed at all, have usually been dismissed as useless, and unreliable in comparison toavaliable lat in, christian material. The Arabic sources themselves are indeed complicated, but this viewpoint has generally been held because of attitudes towards the Islamic period in Spanish history, also several Arabic Chronicles survive which treat in sparse or great detail the conquest of al-Andalus and the actions of Tariq ibn Ziyad and Musa ibn Nusayr and, later, of ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Mu’ awiyz {Dahm, Murray. “The Other Side: Arab Sources on the Conquest of Al-Andalus.” Medieval Warfare 1, no. 3 (2011): 10-12. Accessed May 28, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48577857.}, this is understandable because most sources have contradictions and are difficult to use because of personal or ideological biases and since we can’t make out how the conquest took places, there are several unanswered questions and this can get complicated if many resources aren’t use because each and every one has it’s own bias and perspective of how the conquest went down. in the realm of Al-Andalus an era of unique cultural infusion developed alongside a constant conflict for dominance. Although tolerant and independent, Al-Andalus was far from harmonious and the Umayyad provincial establishment was simply the beginning of the struggles for political legitimacy, the battles for military supremacy, and a tide of glory that would ultimately crest in the victorious campaigns of one powerful general {Ford, Galen. “The Caliphate of Córdoba: Historical Introduction.” Medieval Warfare, vol. 5, no. 4, 2015, pp. 6–9. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/48578470. Accessed 28 June 2021}. Traditionally the invocation of al-Andalus has been understood as a purely nostalgic gesture, and more recently as a reenactment of medieval conflict. On 1 hand, this study establishes that al-Andalus is indeed a key element in narratives of identity and that paying attention to the rhetoric and symbolism employed reveals how various types of oppression are reiterated, on the other hand, this inquire reveals that many writers and filmmakers depart from traditional invocations of al-Andalus and creatively reinterpret the past. This little piece is a synopsis from the book The Afterlife of an-Andalus: Muslim Iberia in contemporary Arabic and Hispanic narrative, The Afterlife of al-Andalus examines medieval Muslim Iberia, or al-Andalus, in twentieth and twenty-first century narrative, drama, television and film from the Arab world and its diaspora, as well as from Spain and Argentina {“The Afterlife of Al-Andalus: Muslim Iberia in Contemporary Arab and Hispanic Narratives: A Synopsis.” Middle East Report, no. 284/285, 2017, pp. 55–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45198529. Accessed 28 June 2021}.

In seeing the big picture and recognizing the different points of view from each source from both the primary and secondary, I can understand that the primary sources could be the ones closest to the original information about the conquest and even though they each have different narrations of it they all had useful and well detailed facts. The dates and many persons mentioned many not be accurate or true but the facts each of them gave different elements that were not found in other accounts and each had their own contains of elements that could not be compared to each other. The secondary source was from a journal article which has been avoided to be use because of the ideals it has and that tells you that the interpretation use might not have enough useful details needed and the other source is from a book the Afterlife of al-Andalus which can be used to focus on the role of invocations of al-Andalus in relation to questions of culture, religion, sexuality and gender. With reading and understanding each source you get to have a big picture of how each of them have self-knowledge and perspective of what the want the readers to understand, each source apply accounts for differences and somewhat similarities.

]]>

Crusading Impact on Christian Iberia

Luke Frolick

History 365 Medieval Spain

June 27, 2021

Throughout European history, Iberia had the unique distinction of sustained religious tolerance in comparison to its neighboring countries. While conflict still existed, the majority of it stemmed over rulership, with most rulers allowing some sort of religious freedom. When the Crusades began, the Roman Catholic Church declared Christian supremacy which was enforced with war and violence. The goal was to take Jerusalem back from the Muslims and eradicate them. While a fury rose up over Europe, it didn’t take hold in Iberia immediately. Through persistence of the Church, we’ll look at how Christian extremism was able to erode relative tolerance by focusing on this one side of the conflict.

The Umayyad Dynasty began rule in Iberia in 756, with its capital in Cordoba. It encompassed all Iberia but a few small Christian kingdoms in the North, and part of Northern Africa. This dynasty prospered and in the tenth century, it was one of the wealthiest nations at the time and a major cultural center. After the collapse of the Cordoban caliphate in 1031, the unity under a single ruler collapsed with it. Smaller taifa kingdoms from across Iberia competed with each other for supremacy. As some kingdoms had wealth, but not enough people, they hired outside protection through mercenaries. The gold offered was enticing to the Christian lands in the North, and so Christian kingdoms entered into alliances with the taifa kingdoms. This caused infighting and conflict between mercenaries whom had no religious affiliation, were Christians, Muslims or Christians alongside Muslims. Religion played little to no factor in any of the fighting.

An example of the most famous mercenary was the Castilian nobleman Rodrigo Diaz, commonly referred to as El Cid, who lived from 1045-99. Through his military career, he served under the Christian Kings Fernando I of Leon-Castile, his son Alfonso VI, then followed by fighting for the Arab Muslim emir of Zargoza.[1] After this service, he set up his own army, made up of Christians and Muslims. From 1089 he fought independently until he took the city of Valencia, where he set himself up as taifa ruler.

Chronicle of the Cid, a medieval document covering the life of Rodrigo Diaz, comments on taking the city of Valencia. Though a predominantly Christian city, the Cid ensured both groups would be able to live alongside each other. “He commanded and requested the Christians that they should show great honor to the Moors, and respect them, and greet them when they met: and the Moors thanked Cid greatly for the honor which the Christians did them.”[2] Although the Cid clearly had no religious motive in his exploits, he was later held up as a Christian warrior, highlighting specific battles. This was not the first or only time events would be appropriated for specific religious goals.

The Chanson de Roland (Song of Roland) is an early example of Christian propaganda to fuel the Crusades and Reconquista in Spain. The original eighth century ballad, passed down orally, recounted the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, where Charlemagne’s army is ambushed by Basque rebels on their return to France from Spain. When eventually written down in the eleventh century, details were drastically changed or removed by the author to create a distinctly religious conflict in the narrative. Left out were details that Charlemagne allied himself with the Muslim ruler of Saragossa on his expedition into Northern Spain. The Christianized Basques were turned into demonic, pagan, Islamic barbarians. The entire perspective of Christians fighting Christians is removed. The battle changed into a large scale martyrdom of Christian Knights. Roland was one such knight and portrayed the hero, fighting for Charlemagne. His battle cry, “Pagans are wrong, Christians are right” creates a black and white narrative, with clear distinctions as who is right and wrong.[3] The song concludes with Roland receiving the highest divine reward upon death, “And God sent to him his cherubim, and St. Michael of the seas, and with them went St. Gabriel, and they carried the soul of the count into paradise.”[4]

These stories of heroism were also backed by papal support for religious conflict. In rallying support for the Holy Crusade to take Jerusalem, Pope Leo IV, followed by Pope John II made multiple declarations from 847-848, called “indulgences,” as rewards for killing Muslims. These indulgences would act as a penance, absolve one of nearly all sins and guaranteeing them a heavenly resurrection, among other blessings.[5] Initially only applying to the Franks, in the areas that would become France, these indulgences proved popular among the people. They would later extend to pilgrims to encourage taking Jerusalem and in 1089 and 1091, Pope Urban II included the same indulgences to campaigns in Spain. The First Crusade to Jerusalem would prove more appealing, even to Spanish Christians,[6] however, the seeds were planted by that declaration to increase religious fervor in the decades to come.

As the twelfth century continued, the Christian influences previously mentioned began to have a greater hold on Northern Europe. The Chronica regia Coloniensis (Royal Chronicle of Cologne), a historical record written in the second half of the twelfth century, contains a series of letters attributed to a Bishop of the Roman Catholic diocese of Porto. These letters set a precedent for future perceptions of Iberian conflicts from the late eleventh through the early twelfth century, the time surrounding the First Crusade. The conflicts are described as an extension of the Eastern Crusades, claiming suffrage of the Iberian Christians at the hands of the Muslims. As the Second Crusade was beginning to take shape in the mid-twelfth century, the Christian participants from Northern Europe felt obligated to support the war effort, rallying under religion.[7]

In 1147, Pope Eugenius III declared a Second Crusade. The call was made to take back Edessa, a county set up during the First Crusade, which was captured in 1144. In addition, there would be an effort to take Damascus.[8] Many answered the call, as penance, devotion to God and for glory, ideals the Church had been propagating for well over a century.

During this time, Alfonso VII of Castile had been involved in regional conflicts to assert his claim as King over Castile and Leon. Despite being a conflict over rulership, Alfonso took advantage of papal support for the eradication of the Muslims and altered his motivations to that of being a holy war. This came along with the benefits of indulgences and would garner him more support.[9] It would be at the siege of Lisbon that Alfonso would be able to take advantage of the traveling Crusaders from the North.

The most efficient route to the Holy Land was by ship. Many of the Crusaders from Northern Europe sailed along the East Coast of France, around the entire Iberian Peninsula, then West across Southern Europe towards Jerusalem. Heeding the call, the initial fleet that launched in 1147 was fairly substantial. As they approached Lisbon, on the Western coast of Portugal, they saw that it was besieged by Alfonso VII. As a predominantly Muslim city, Alfonso was able to convince this force to aid in taking Lisbon. A document from the time describes the city as “the basest element from every part of the world had gathered there, like the bilge water of a ship, a breeding ground for every kind of lust and impurity…”[10] which fueled the Crusaders righteous indignation. Despite the city surrendering relatively quickly, there were many problems that arose, both during and after the siege.

Among Alfonso’s Portuguese contingents, many of the troops that arrived were from different countries, but also from splintered groups inside those countries. “Norman, Anglo-Norman, Frankish, Gascons, Flemish, Frisian and Rheiners”[11] made up the siege forces, with many of them in conflict back in their homeland. Being forced into relatively close quarters created disputes which could have worsened had the siege lasted longer. After the siege ended and the terms for surrender were made and accepted, due to tensions from culture, religion or both, they were violently broken. “The men of Cologne and the Flemings … did not observe their oaths or their religious guarantees. They ran hither and yon. They plundered. They broke down doors. They rummaged through the interior of every house. They drove the citizens away and harassed them improperly and unjustly. They destroyed clothes and utensils. They treated virgins shamefully. They acted as if right and wrong were the same. They secretly took away everything which should have been common property. They even cut the throat of the elderly Bishop of the city, slaying him against all right and justice…”[12] The same document then mentions how the Normans and the English “for whom faith and religion were of the greatest importance” stayed true to their oaths and “obligations of faith.”[13] This account tries to give reason and blame to the chaos taking place, as it would have been too rampant and extensive to exclude.

The success in taking Lisbon further emboldened Crusaders to attack cities along the al-Andalusian coast. While the Almoravids of al-Andalus were defending themselves from the Almohads, an extreme Islamic group from Northern Africa, Crusaders were left with little opposition. By 1149, along with Lisbon, the tifa of Tortosa and the port city of Almeria were taken.[14]

The failure of the Second Crusade was characterized by not being able to take Damascus. Like the different groups fighting in the siege of Lisbon, lack of cohesion, and very likely conflict between the armies of France, Germany and Jerusalem played a part in that failure. The kings of each respective country blamed each other for their defeat.[16] Turning attention away from this failure, victories in Iberia were emphasized to prove Crusaders still had divine support. The concept of Reconquista, taking back previously Christian lands from the Muslims, became more propagated. It would increasingly be used in reworking past conflicts and as a basis to garner support for the Catholic Church and Christian rulers.

Throughout the next half century, rulership was contested in Iberia in many conflicts, mainly due to politics, not religion. Through the Third and Fourth Crusade, Spanish Christians were comparatively involved very little, being more concerned about their living conditions at home. Outside forces did pose a threat along the coasts of Iberia as indulgences were still granted to fighting the Muslims in Spain. Northern Europe still circled the coasts of Iberia to get to Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Crusaders were eager to raid and plunder on their journey, with little regard as to whether they were sacking Christian, Muslim or mixed communities, taking advantage of the civil strife in the area.

In 1213, Pope Innocent III in preparation for a Fifth Crusade, revoked the offer of indulgences in Spain, except for the Spaniards themselves. This was to focus on the war in taking back Jerusalem, rather than Spanish exploits.[17]

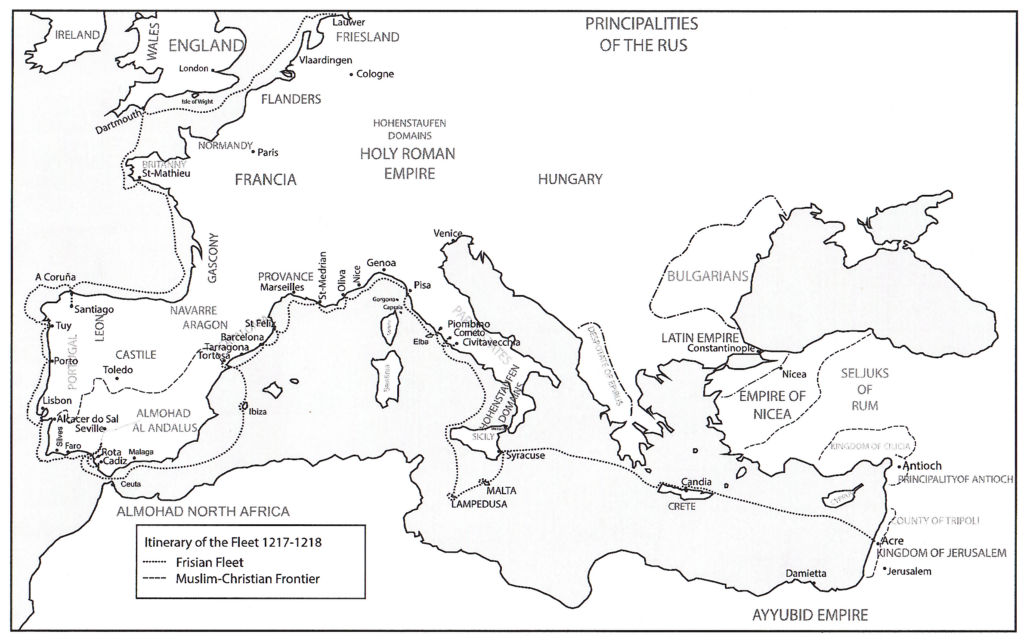

With the Fifth Crusade beginning in 1217, despite the cancellation of the indulgences, Crusaders traveling the Iberian coast continued their raiding and aggression on their journey to the Holy Land. Over a century of propaganda, holy Christian wars and demonizing the Islamic people had rooted itself in the minds and culture of those participating in this Crusade. An eyewitness account, from the Dutch-Latin document, De Itinere Frisonum describes the journey of a Frisian fleet from its departure on May 31, 1217 to April 26, 1218 when it lands in Acre. The document carries the theme of Christian redemption along with references to previous Crusader exploits and victories in Iberia, such as the conquest of Lisbon among a few others. This fleet was no different and continued to sack Andalusi cities. The reason for this, was in imitation of previous Crusaders. Attacking and raiding these cities was just as much a part of their Crusade as fighting in the Holy Land. While this document wasn’t heavily circulated at the time, by the end of the sixteenth century, this story was well known in Friesland.[18]

As the map shows, the journey of the Frisian fleet holds very closely to the routes described in the earlier crusades, even landing in some of the cities and ports of past exploits. This journey was a pilgrimage itself, in following their ancestors or heroes. Until the crusades ended, the act of pilgrimage and raiding continued, whether they had papal support or not, because it had become a tradition.

These external influences and attitudes were the beginning steps in creating specifically religious conflict throughout Iberia. Religious minorities would find it increasingly difficult to live and cities and territories would be increasingly pressured to be either Christian or Muslim.

As the long rule of the Caliphate came to an end, the power vacuum left behind created smaller kingdoms which were in a state of constant struggle for domination with each other. With the Roman Catholic Church trying to increase its influence over Europe, Iberia continued to be the exception. Religious tolerance was more prominent than in other countries. While there was still conflict, it was mostly about land and rulership as opposed to religion. Christians and Muslims fought alongside and against each other, and amongst themselves. Through creating a narrative of Christian verses pagan, while rewriting historical events, and prejudiced propaganda, the Church slowly eroded Christian Muslim sympathies. Through the onset of the Crusades, Northern Europe slowly imposed Crusader ideology throughout Iberia. With the invention of Reconquista, indulgences and violent tradition, the true complexity of their history slowly faded into simplistic battles of religion.

Bibliography:

Allen, S. J., and Emilie Amt. The Crusades: a Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, and I. Butler. “The Song of Roland.” Essay. In The Crusades: a Reader, 22–24. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, and R. Southey. “Chronicle of the Cid.” Essay. In The Crusades: a Reader, 288–91. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, C. W. David, and J. A. Brundage. “The Conquest of Lisbon.” Essay. In The Crusades: A Reader, 292–96. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Allen, S. J., Emilie Amt, O. J. Thatcher, and E. H. McNeal. “Early Indulgences.” Essay. In The Crusades: A Reader, 17. North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Ayala, Carlos De, Francisco García Fitz, Santiago J. Palacios, and Lucas Villegas-Artistizabal. “Las Guerras Peninuslares Contra Al-Andalus: Una Vision Desde Las Fuentes Narrativas Unltramontanas (c. 1064-c. 1217).” Essay. In Memoria y Fuentes De La Guerra Santa Peninsular (Siglos X-XV), 103–29. Madrid: Trea, 2021.

O’Grady, Selina. In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance. London: Pegasus Books, 2020.

Rosenthal, Joel T., Paul E. Szarmach, and Lucas Villegas-Aristizabal. “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217-1218.” Essay. In Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History 15:67–149. 3rd Edition. Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2021.

Tyerman, Christopher. The World of the Crusades. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

[1] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 288.

[2] S. J. Allen, Emilie Amt, and R. Southey, “Chronicle of the Cid,” in The Crusades: a Reader (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 288-291, 289.

[3] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 117,118.

[4] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Song of Roland,” in The Crusades: a Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 22-24, 24.

[5] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “Early Indulgences,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), p. 17.

[6] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 291.

[7] Carlos De Ayala et al., “Las Guerras Peninuslares Contra Al-Andalus: Una Vision Desde Las Fuentes Narrativas Unltramontanas (c. 1064-c. 1217),” in Memoria y Fuentes De La Guerra Santa Peninsular (Siglos X-XV) (Madrid: Trea, 2021), pp. 103-129, 117.

[8] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 136.

[9] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 173.

[10] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Conquest of Lisbon,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 292-296, 293.

[11] Carlos De Ayala et al., “Las Guerras Peninuslares Contra Al-Andalus: Una Vision Desde Las Fuentes Narrativas Unltramontanas (c. 1064-c. 1217),” in Memoria y Fuentes De La Guerra Santa Peninsular (Siglos X-XV) (Madrid: Trea, 2021), pp. 103-129, 116.

[12] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Conquest of Lisbon,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 292-296, 295.

[13] S. J. Allen and Emilie Amt, “The Conquest of Lisbon,” in The Crusades: A Reader (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2014), pp. 292-296, 296.

[14] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 137.

[15] Christopher Tyerman, The World of the Crusades (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 295.

[16] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 137.

[17] Selina O’Grady, In the Name of God: The Role of Religion in the Modern World: A History of Judeo-Christian and Islamic Tolerance (London: Pegasus Books, 2020), 296,297.

[18] Lucas Villegas-Aristizabal, “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217-1218,” in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, vol. 15 (Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2021), pp. 67-149, 76-80.

[19] Lucas Villegas-Aristizabal, “A Frisian Perspective on Crusading in Iberia as Part of the Sea Journey to the Holy Land, 1217-1218,” in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, vol. 15 (Tempe: ACMRS Press, 2021), pp. 67-149, 109.

]]>LESSON TOPIC: Jews and Conversos in Medieval Christian Spain

AIM: Give the students knowledge on the identities of Jewish and Converso people in Spain at the time of Christian rule.

OBJECTIVES: Students will be able to understand why Jews converted to Christianity and the struggles that they faced as Jews and as Conversos. Using this knowledge they will produce a piece of work reflecting what they understand.

MATERIALS: Lesson plan, video, printed copies of the Disciplina clericalis primary document, blank papers, pencils.

WARM UP:

We begin by gathering in a circle to start the lesson. Then start by talking about any personal/school/current events. Next we will review what we learned in the last class. I will then briefly explain what will happen in today’s class.

VISUAL COMPONENT:

This is meant to be the light and fun part of the lecture. It is to get us thinking about the topic. The video I made is unlisted on YouTube and I emailed you the link.

Here is the script:

The Lex Visigothorum is a set of rules created during the Visigothic Chrsitian rule over Spain.

Woah woah woah, what is Visigoth and where is Spain?

Well take a look at this: the Visigoths were a Christian group that conquered Roman Spain in around 507. Over the course of the 6th century many converted to Christianity and by the end of the century most of them had.

Why?

From intermarriage with the Catholic roman Iberians who greatly outnumbered them and also from political and social pressures.

Ok, this makes more sense.

Lets head back to the studio

Now what was the Lex Visgothorum again?

A set of rules created by the Visigoths!

Can I see it?

I don’t have a picture of the Lex Visigothorum itself, but here is a photo of the Liber ludicum from 1600 that was published with the Lex Visigothorum

So this set of rules must have lasted a long time

It sure did

Who exactly made it?

Well it was first put into order in 654 under King Recceswinth then revised by king Ervig.

Why are we talking about it?

Many of the sections of this Law Code address Jewish people that convert to Christianity but secretly still practice Judaism.

Was that allowed?

You’re about to find out!

So what are we waiting for!

Let’s start by talking about the testimony of faith by converted Jews, this is what the Jewish people would have to recite when they converted to Christianity. I am just going to read some important parts of it. First off, they must admit that they previously did not embrace the Christian faith to full extent, here is that part: “…whereas the perifidy born of our obstinacy and the antipathy resulting from our ancestral errors influenced us to such an extent that we did not then truly believe in our Lord Jesus Christ and did not sincerely embrace the Catholic faith, therefor now, freely and voluntarily, we promise Your Majesty for ourselves, our wives, and our children, by this, our memorial, that henceforth we will observe no Jewish customs or rites whatever, and will not associate, or have any intercourse with any unbaptized jews. Nor will we marry any person related to us by blood, within the sith degree, which union has been declared to be incestuous and wicked. Nor will we, or our children, or any of our posterity, at any time hereafter, contract marriage outside our sect; and both sexes shall hereafter be united in marriage according to Christian rites.”1 What do you say to this?

This tells me that they once already converted to Christianity but did not believe in the Christian faith fully

This is right

It must have been difficult for early converts as they could not see or have relations with any Jew that wasn’t baptized

Very true and this might be why some of them converted but did not follow the rules of conversion. In the document it lays out more rules converts must follow, do you think you could guess any?

Hmmm, well I would suppose they couldn’t partake in any Jewish holidays.

That’s right, it says “We will not celebrate the Passover, Sabbath, and other festival days, as enjoyed by the Jewish ritual.”2

It wouldn’t possibly be so strict to restrict what foods they eat, would it?

It would, you must not make any distinction in food or have any Jewish ceremonies. In fact, they even have to eat meat with no disgust or dislike even if it was against their Jewish beliefs.

Wow, that seems like its taking it too far.

Religion was taken very seriously at this time.

What happened to those that did not follow these rules?

It says in this document: “…in the case a single transgress or should be found among our people, he shall be burned, or stoned to death, either by ourselves, or by our sons. And should Your Majesty graciously grant such culprit his life, he shall at once be deprived of his freedom, so that Your Majesty may deliver him to be forever a slave to anyone whom Your Majesty may select…”3

This is a very severe punishment. It seems that although the Jews had some sort of religious freedom, they could not change their minds once they became Converso’s or coveted Christians.

This is true and though they did have religious freedom, there was much coercion for them in medieval Spain to convert. This includes the violent attacks against Jews in 1391 and the expulsion of the Jews in 1492.

Ahh I see, so it was technically labelled as a choice but it wasn’t really a fair choice

Exactly, now you’re getting it!

READING COMPONENT:

Teacher: May I please ask the class to now read the document that was handed out titled Disciplina clericalis, early 12th century. We will be discussing this document afterwards.

DISCUSSION:

Discussion points:

What can the Disciplina clericalis tell us about the experience of a converso?

– They can honestly and passionately change faiths, not just pretend to do so

– He seems truly moved by his faith, in fact it was his inspiration for writing this book.

– They must always be on the defensive side and be prepared to prove themselves.

In what ways do we see the rules of the Lex Visigothorum reflected in Alfonsi’s writing?

– When Alfonsi writes on hypocrisy he states “‘Imagine a man who both openly and secretly shows himself as obedient to God…’”4. He is shaming those who hide their obedience to God. This reflects the section in the Lex Visigothorum when Converso’s must be against anyone who tries to take back the Jewish religious or traditional lifestyle. In his mind, he may see this as hypocrisy because many self-proclaimed Converso’s still secretly practiced Jewish traditions.

– In the Lex Visigothorum they swear to “…uphold the Catholic faith…”5. Alfonsi certainly reflects that he has been upholding Christianity and that he has a fear of God in him that drives his faith.

What kind of values and ideas might converso’s have that Jewish people who do not convert and Christians do not? Think about how many Jews were coerced, punished, killed or exiled for being Jewish and the struggles of converting faiths.

– In the Disciplina clericalis it is clear that trust and loyalty are very important when he tells the story of the half friend. This may not be something Christians have to go through as they do not need the extra defence or security on their friendships for they were not once at risk or a minority. For conversos, it is important for them to have people of like-mind and whom they can count on and trust for although they are now Christian, they are still of Jewish origin.6

– Another example in Disciplina clericalis is when Alfonsi tells the story of The Anti, the Cock, and the Dog. This describes needing to be smarter, stronger and nobler than others (animals). I interpret this as a means of proving himself to others, which is something a converso may need to do since they have not been Christian their whole life. 7

– After analyzing parts of the Lex Visigothorum, we are able to hypothesize that these Converso’s would be very resilient as they have had to completely change their lifestyle, religion and most likely their social groups as well. They would also have to be quite brave to be able to convict fellow conversos, including friends and family, of being traitors to the Christian faith knowing the consequences.

LECTURE:

When looking at a topic in history, it is not only important to look at primary sources, but also at secondary sources. Why is this? (to understand other biases and how other scholars interpret history). Today’s lecture will focus on one more primary source and two secondary sources to further understand the identity and life of Converso’s in Christian Iberia.

We are going to begin by discussing a primary document from a bit later than both the previous documents. The first video we watched today referenced anti-Jewish violence that occured in 1391. I think it is good for us to look at that in a bit more detail. The information I am providing for you on the riots that occurred comes from the primary document Hasdai Crescas’s Letter to the Community of Avignon, 1391. In this letter, it explains that on June 4, 1391, the Christians came into the town of Seville which had many Jewish families and caused death and destruction with fire and other means. Here is a passage from this document: “The majority, however, changed their faith. Many of them, children as well as women, were sold to the Muslims, so that the streets occupied by Jews have become empty. Many of them, sanctifying the Holy Name, endured death, but many also broke the holy Covenant.”8 This document can tell us that many Converso’s may have only converted to Christianity because of fear, which may not be a very good basis for their new faith. This may have caused instability in their later identity as many of them most likely secretly still hold allegiance to their former faith.

Now we are going to finish by connecting the works of other scholars to our knowledge from primary documents. David Nirenberg wrote an article called “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation: Jews and Christians in Medieval Spain”, in this he discussed the effects of marriage, sex and relation laws between Jews, Christians and Converso’s. He argues that by having rules against intermarriage and sex it further segregates the Converso’s from the Christians. Here is a quote from the article: “In the mid-1430s; a number of people began to articulate the view that converts and their descendents were essentially different from (that is, worse than) “natural” Christians and therefor (among many other things) unmarriageable”9. Nirenberg, however, believes that this segregation that is made is not because of their closeness to being Jewish, but for the fear that their children or future generations will become Jewish. So if we think about Jewish identity and how it would form from Nirenberg’s perspective we see that they were very excluded from both Christain and Jewish groups, this would have pushed them together to form a unique identity. This perspective on Converso’s identity is backed up as well by scholar Benjamin Gampel. His article “The “Identity” of Sephardim of Medieval Christian Iberia” explains that as Jewish people converted to Christianity they began to construct their identities on both Jewish and non-Jewish elements. He also argues that these new identities are not uniform, which makes sense since they are so new. He explains that differences in culture and patterns contribute to this diversity of identity.

When we look at our analysis of the three primary sources and cross reference them to our secondary sources, we notice a pattern. These conversos were careful, prepared, brave, unique, unstable, and resilient. They have been through struggles unique to them. We are not going to move on to your assessment, which is in the form of an assignment.

ASSIGNMENT:

Students must take what they learned from each section of the lesson (video, reading, discussion and lecture) and complete an assignment.

Students must make a mind map on a blank piece of paper that includes all the characteristics, events and themes that make up the identity of a conversation. They can also either draw a converso in the middle or simply define a converso in one sentence. Below is an example:

REFLECTIVE CIRCLE:

Finishing off by asking the following questions to the class:

On a scale of one to ten how much did you enjoy this class?

We are going to go around the circle to either say one thing you learned today or one thing you would like to add to today’s lesson

How has your perspective changed during this class from what you might have known before on the topic?

Footnotes:

1 Lex Visigothorum (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 24.

2 Lex Visigothorum, 25.

3 Lex Visigothorum, 25.

4 Alfonsi, Petrus, Disciplina clericalis, early 12th century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 201.

5 Lex Visigothorum, 24.

6 Alfonsi, Disciplina clericalis, 201-202.

7 Alfonsi, Disciplina clericalis, 201.

8 Hasdai Crescas’s Letter to the Community of Avignon, 1391, (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2016), 165.

9 Nirenberg, David, “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation: Jews and Christians in Medieval Spain,” The American Historical Review 107, no. 4 (2002): 1092.

REFERENCES CITED

Alfonsi, Petrus. “Disciplina clericalis, early 12th century.” Translated by P.R. Quarrie. In Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources, ed. 2., edited by Olivia R. Constable, 199-202. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

“Lex Visigothorum.” In Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources, ed. 2., edited by Olivia R. Constable, 23-26. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Gampel, Benjamin R. “The “Identity” of Sephardim of Medieval Christian Iberia.” Jewish Social Studies, New Series, 8, no. 2/3 (2002): 133-38. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4467632.

Nirenberg, David. “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation: Jews and Christians in Medieval Spain.” The American Historical Review 107, no. 4 (2002): 1065-093. Accessed May 28, 2021. doi:10.1086/532664.

Saperstein, Marc, and Marcus, Jacob Rader. The Jews in Christian Europe : A Source Book, 315-1791. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2016. Accessed May 28, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central.

]]>

Andalusian Muslim women’s gender expectations in relation to social class, time, and comparable laws were determined by women’s social status in Medieval Iberia under Muslim rule from 10th century to 13th century. By reflecting on these gender expectations that were considered virtuous by looking at the way women were behaving under different circumstances from different narrative in primary sources and secondary sources within the topic, in order to gain holistic understanding of the social and political context, one other aspect of this research is to see if these concept had changed over time from the golden age of Umayyad Caliphate until the final Taifa period where Muslim dominance in Iberia waned. In order to compare and contrast these works, elements we must look at from the two primary sources are: the perspective and the narrative of the story; what the story is about; social status of the characters;the reflection of gender expectation through the literature.

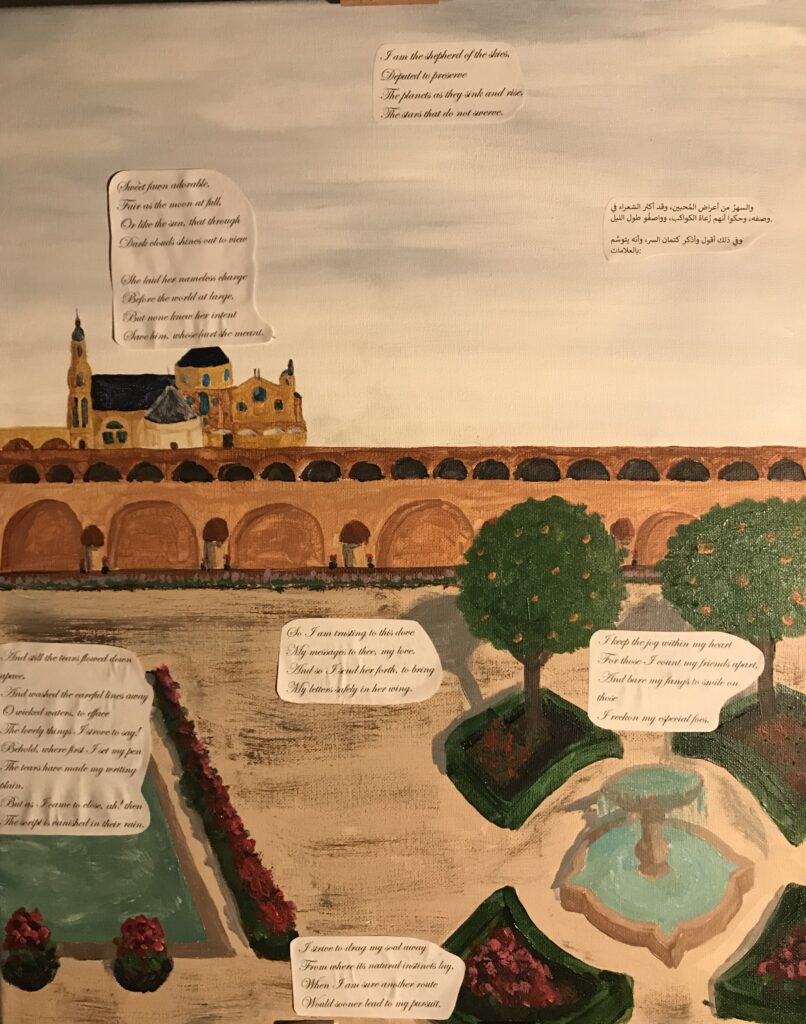

The passage The Ring of the Dove written by Ibn Hazm was written approximately from the beginning of 10th century in Cordoba.(Constable & Zurro, 2012) It is a famous piece of literature that was compared and contrasted by many authors in medieval writing until today. The author Ibn Hazm fell in love with a slave girl in his household when he was a teenager, and the text itself demonstrates his feelings for her changed overtime during the political influence that was brought to his family during the period of Umayyad civil war. Ibn Hazm’s father worked as a Vizier for Almansor, but his family was forced into hiding after Almanzor died and Hisham II took the throne for the second time, so basically their family is on the opposite side of the power. Ibn Hazm went back to his hometown Cordoba after a few years, he met the slave girl again at a relative’s funeral, however, he realized to him, her beauty faded away when she was not protected under the household.(Dangler, 2015)

In this case, Ibn Hazm was fond of the girl’s avoidance, delicacy, chastity and purity; what was attractive to him was the way she kept herself distant. Ibn Hazm tried to approach her during a family gathering, but he did not try to break their distance, but in a position of spectator of her change after they had left Cordoba. However, she does not appear charming to him anymore after the family moved away without her, so she has to find a living on her own. Meanwhile, Ibn Hazm criticized that she was losing her beauty because of lack of maintenance overtime.

The text “Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad” translated by Barbara Cynthia Robinson from Arabic is a story that happened in around 13th century Al-Andalus, it comes from a female narrative of a ajuz, which could be understood as matchmaker, someone that helps setting lovers up for meetings.(Cynthia Robinson, 2007) This love story happened between the Merchant’s son from Syria, Bayad, and the slave girl of hajib’s daughter Sayyida named Riyad. The matchmaker set Bayad and Riyad up at a gathering in Sayyida’s garden, where everyone sang songs and poems. While Bayad admitted his crush on Riyad in an obscure way, by complimenting on her beauty, which everyone was impressed about, Sayyida was furious at Riyad while she realized it and responded to him in a much more blunt and straightforward poem because she was not maintaining the characteristics that she was supposed to, it was a serious problem for Sayyida because she was going to exile her from the household sell her on the market. This manuscript reflects the gender expectations in 13th century Al-Andalus and provides some insight into the virtues that women should have in relation to their social class.

For instance, Riyad, as a slave girl has the lowest social status, Bayad and Sayyida have more power to make decisions in the society. Thus, the one obvious outcome of Riyad expressing love directly to Bayad was considered rude and out of character, and was heavily criticized in the story. In comparison, Bayad was able to openly sing the song to Riyad without causing any troubles. According to Bayad, while he was describing Riyad, he liked her and praised her characteristics for being shy, beautiful and silent.(Cynthia Robinson, 2007, p. 33)Moreover, when the old lady was trying to comfort Sayyida for Riyad’s action, she stated that “for we are all women and we have no reason and so we don’t know how to guide ourselves— how can we guide ourselves, then? There’s no blame in what Riyad did…” she used ‘ourselves’ in the choice of word specifically, this could indicate that the idea of the dependant as the stereotype for muslim women in 13th century Iberia exists regardless of their social status.(Cynthia Robinson, 2007, p. 36) Though Sayyida’s words while she was angry suggested that she had the power to decide for her slave’s life since Sayyida’s father wanted Riyad as his mistress, which shows upper class males are able to openly express their love affection but women have much less likely chance to do so, near the end of the manuscript, it was revealed that the person who kept the lovers from seeing each other was the hajib, meaning that the right to choose their loved ones is largely based on one’s social status. Meanwhile, more than one spot in the story stated that women are supposed to be silent, beautiful, chaste and dependent.

There are some similarities of what both women were facing in the story The Ring of the Dove and Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad. Both love stories began with love at first sight from the male perspective without having the process of further knowing each other, and kept a moderate distance between each other because of the need to examine if the woman was being unrevealed and chaste. Both stories highlight men’s affection and social acceptance for women was largely based on females’ restrained, meekness and purity. It was shown in The Ring of the Dove where Ibn Hazm finally met her at the family gathering when she was trying to stay away, it also shows when he saw her again years after saying all her beauty and attractive traits faded away, which including her fragileness and shyness. It is similar in Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad after Riyad expressed her feelings to Bayad in the poet singing activity, everyone in the garden was in shock that she did such an action. Riyad was punished by her master, Sayyida for this inconsiderate act, which proved that it is not socially acceptable for women to do so directly. While the identity of both female characters were slaves in these stories, the male character in both stories had higher social status than women, Ibn Hazm was a poet and came from a well-educated elite family, Bayad was a Syrian merchant’s son. While the male characters maintain their higher social status, there is no sign of forcing the girl to be together in both stories, except for the hajib, Sayyida’s father, who tried to ask to take Riyad through her daughter. It is slightly confusing and contradictory that through Sayyida’s words it seems like slaves in these households can just be traded and sold in the market. However, unlike the hajib, both Ibn Hazm and Bayad showed their respect when they were going to approach the women they love, although Riyad and the slave girl in The Ring of the Dove were both from lower social status.

Although there are some common themes in women’s life related to love affairs in both of the stories, there are also many elements that can influence the reality of their life. First, the perspective of these two texts are distinctively different, thus it would be subjective when the individual is judging or recalling certain events, which should be taken in consideration while investigating the story. The narrator from The Ring of the Dove, Ibn Hazm, his philosophical and political experience the changed for himself, also lead to his father’s pass away, according to the textbook, his feelings for the slave girl is also an implication for his hometown changed and declined throughout the first fitna, so the metaphor was also used on his past experience with the one he loved.The mindset when Ibn Hazm was creating in this book also constitutes his cherish to the past. Whereas Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad has a completely different narrative, this story also comes from the ajuz that experienced it, however, the perspective shifts around the main characters. However, the effect of the ajuz is actually a treasure and cherishes the appearance of true love.(V. Besprechungen, 2009, p. 364) Furthermore, sometimes women’s ability and events are marginalized in historical literature and documents, making it challenging to interpret when connected to other background information. (Shamsie, 2016) In these two texts, both muslim women had very different endings, in The Ring of the Dove,the slave girl did not overstep the boundary, facing Ibn Hazm’s love and admire, she still held her behaviour of moderation and self-control, even if toward the end when Ibn Hazm changed his emotions, she did not change. In Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad, Riyad did not choose to follow the widespread and accepted idea of holding in her own emotion, but to follow her heart to express her love to Bayad. At the end, Bayad and Riyad reunited successfully, but the voices against them from the society emerged in the literature during their effort towards reunion.

In relation to Islamic law, the reason women or people in general show less affection is also because their spirit should be submissive to God, so to distribute this energy to the person that they love is considered wrong in Islamic definition.Because one’s soul should not be dominated by a human being.(Benaim de Lasry, 1981, p. 136) This point can be supported with quotes from the poems in Hadith Bayad Wa Riyad, “Love holds absolute power over my soul… It’s terrible power breaks me to pieces through desire, causing me pain and tears.” “And melted my body from the pains of love–I was left without my soul.” When they are describing love in their literature, it comes out as comparatively negative phrases although they are passionate about each other. The indirect expression continued in the 13th century, where ajuz acted like “go-between” in the lover and the beloved to balance it out.(V. Besprechungen, 2009) Furthermore, only men in islamic iberia were allowed to permit marriages, very few women at the time had the right to decide on their own marriage.(Coope, 2017b, p. 89) According to Coope, in Earlier Al-Andalus, around 9-10 centuries, because women’s action were not taken seriously in the society, the fact that the patriarchal society reinforced the idea that in relationships and marriages that women should be submissive and distant, which continues to have impact on how islamic society went about defining intersex relationships, and expected women to be that way.(Coope, 2017a)

In conclusion, by coming to understand these gendered relationships, with the focus on female gender expectations in Islamic Al-Andalus, interpreting these relationships to other social elements such as social and legal systems the nature of patriarchal society is revealed. The two texts, regardless of social status, it is not socially acceptable for Islamic women in Al-Andalus to express their love directly. Though better social status brings a variety of possibilities to their own choices and sometimes even other people from lower social status. This is a symptom of larger developments in the Islamic world but the unique scene painted by these authors in Al-Andalus provides us with a means with which to view these trends through.

Reference

]]>Spain in 1391 was encompassed by violent acts committed by Christians towards the Jewish population. This conflict was based around the frustration of Christians trying to show the superiority of their religion to the Jews. This essay will be discussing the forced conversions of Jews, by Christians in the 1391 riots against the Jews, also known as the Massacres of 1391, for the violence portrayed onto the Jewish communities in Spain. The main ideas we will be looking at in this essay are what led the series of riots to take place, what these riots looked like, the implications left behind after the riots ended, as well as, looking into why Christians believed that they were entitled in forcing Jews to convert to Christianity. To begin this essay the first aspect of the events on 1391 that we will be exploring is what led to the violent conflicts between Christians and Jews. Exploring the idea of the gathering in Seville and the interaction that took place between Ferran Martinez and Hia Ibn Attaben. The Second aspect we will than look into is this massacre, discovering what these violent acts looked like, how Jews were being treated by the Christians and how the riots and massacre expanded throughout the rest of Spain. The third aspect that we will be looking at is the idea of Jews as Conversos, exploring the relationship between Jews, Christians and Muslims, prior to and during these events. As well as, looking at the repercussions of this forced conversion and how Conversos had to adapt to the change in their society and way of living. The last aspect we will look at explores a primary source about the Christian faith, this source is written by a man who has converted from being a Jew to Christianity. This source will be used to show why Christians feel a sense of entitlement to convert Jews out of their religion, and into Christianity, the “superior” religion. I think that each of these aspects we will explore in relation to the 1391 riots and massacres of Jews, really highlight the significance of this event in Spanish history. This is another very important battle of religion, and this time it is Christians trying to prove that their religion is superior and should be the one that is followed by everyone.

This forced conversion of Jews to Christianity was one that was created by Christians insecurities of their faith in comparison to the Jews. In 1388, there was a group of Jews that would gather in order to air their grievances against the archdeacon, Ferran Martinez: “On 11 February 1388, A large crowd gathered before the gates of the royal palace, that Alcazar, in Seville – one of the largest cities in the kingdom of Castille.”[i]. Hia Ibn Attaben was key in bringing people to this gathering, with the intention “to publicly air their grievances against one of Seville’s most prominent citizens, Archdeacon Ferran Martinez, a canon at the cathedral, whose incendiary sermons had been threatening the security of the Jewish community.”[ii] Ferran took advantage of the disputes, encouraging riots against the Jews in Seville. Forcing them to choose between conversion to Christianity or death. The specific site of this gathering was important as it was “one of the most public and visible spaces in the city.” [iii] The gathering was a “diverse representative sample”, showcasing the multitude of different religious orders that all were centered in this area.[iv] The riots that began in Seville spread all over Spain, driven by the idea that Christians were fighting for religious superiority over the Jews, increasing tension among the two groups. In Castille, there was a significant turning point in this battle for superiority where Enrique De Trastanara utilized anti-Semitism to gain an advantage over his half brother. The state of the economy and political realm held a significant influence over how these riots escalated.

One of the riots, the “Massacre of 1391”, had a significant number of casualties and fatalities. Following this event Jews were trying to escape the cities, moving away from the larger cities where violence against them was escalating in frequency and severity. The aftermath of this massacre held significant socioeconomic, social, and religious influence in the two faith groups, “The conversion to Christianity of many thousands of Jews caused by the massacres, forced disputation, and segregations that marked the period between 1391 and 1415 produced a violent destabilization of traditional categories of religious identity.”[v] There was a group of leaders, including St. Vincent Ferrer who wanted to increase the distance between Christians and Jews in two ways, “First, by converting as many Jews as possible to Christianity; and second, by sharpening the boundaries between Christians and those (ideally few) Jews who would inevitably remain in Christian society until the end of time.” [vi] The massacre began to spread and develop in Spain, originating in Seville the violence spread to “Cordoba and Toledo, and then into the lands of the Crown of Aragon.” [vii]During the riots the King of Aragon was becoming frustrated about conversions, not being able to tell who was a “true” or “natural” Christian, and those who had converted from Judaism. From there it continued to spread to Valencia, “By August pogroms raged into the city of Barcelona, on the Mediterranean island of Majorca, and into Northern Spain.”[viii] Prior to the riots in Seville there was a general feeling of contentment and peace between the different religious orders in this area. This abruptly ended when Ferran Martinez took action against the Jews and the pre-existing tensions began to interfere with the previous notion of peace.

The year 1391 held immense significance to the Jews, this is when they experienced the greatest loss of life during the Middle Ages. Jewish, Muslim, and Christian groups were being pushed together in terms of land and communities causing tensions to build and progress into violence, “Their coexistence was not easy, for each of the three religious communities felt at risk, both physically and spiritually, from the others,” [ix] The relations between these groups can be characterized at this point in history by their “punctuated equilibrium”, defined as, “long periods of constant but functional conflict separated by episodes of widespread violence.” [x] Their interactions with each other always had a history of conflict, while sometimes they were able to coexist, this also gave reason for violence towards one another. This year was also significant to Christian groups, when the crisis brought about by the question, “who is a Jew?”, lead to the decay of the Iberian Peninsula. Following this year of violence towards the Jewish groups there was an increase of conversion to Christianity as a protective measure. This was done to keep their jobs, housing, and safety secure following the rioting in previous years. This uptake in conversions increased the discussion surrounding the questions of who a Christian was and who a Jew was; this led to more violence as these questions were considered on a broad scale. The Jews became labelled as the “conversos”, who had to strive to seek the approval of the “true” or “natural” Christians. In doing this they hoped to gain what the Christians had; they yearned for the honor and respect that they were not given as Jews. This need to gain honor and approval was integral in their acceptance in those groups, “Conversos desired to achieve a degree of honor and respect among Old Christians, perhaps both in reaction to, and in order finally to possess, the honor, meaning the prestige, that the law and society had denied them as Jews.” [xi] In an attempt to be able to function in their surrounding environment, after losing so much stability in the massacre and riots, gaining acceptance to Christian groups was significant in re-establishing their communities.

The basis of the superiority that Christians felt over the Jews was rooted in the idea that God is Almighty in power, knowledge and will. The connection to this omnipotent god gave them a sense of superiority over those who didn’t have this direct relationship. There is a commandant in the Christian faith to convert, “as a religious duty to Him [God], as those giving thanks, praising, and glorifying but not comprehending for His essence or apprehending any part of it.”[xii]This is an impassioned view of God and their mission in conversion, seeing God as the creator, the all powerful. As the creator they see God as being involved in the lives of all people, “this, then, is our teaching about the triune nature of the oneness of the creator.” [xiii] Based on this understanding of God as all powerful creator they were not able to comprehend how other religious orders and individuals did not follow their creator. In their view, if God is this all-powerful being, and they are following him, they perceive that they have a certain level of power and entitlement over anyone who did not follow God. So, at this point in time the Christians felt that the Jews were not in line with who God was, but that themselves were. This perception of Judaism, and other religious orders, is the basis on which their fight for superiority is built.

The forced conversion of Jews in Spain in 1391 is a very important aspect that makes up Spanish history. It stemmed from the interaction that took place between Ferran Martinez and Hia Ibn Atabey in Seville. Hia Ibn Atabey, publicly brought his grievances forward to the archdeacon, which as we can see did not go over well. This resulted in Ferran Martinez gaining power and taking his frustration, and sense of revenge out on the Jews, leading to the riots and massacres. These massacres that took place were filled with violence. The idea for Jews was that you either converted to Christianity, you hid and ran away from the violence, or you were killed. This idea developed and expanded all over Spain, and only worsened as time went on. The Jews who did convert to Christianity were than given the title Conversos. However, as conversos they were than trying to start their lives over again. They needed to try and obtain freedom and ability to function in society, while they were still being looked down on by these Old Christians. The last item that we discussed was built around the primary document, discussing the greatness of Christianity. We discussed within the essay that this sense of entitlement that Christians had could’ve come from many different things. The first being that they maybe saw this forced conversion as a calling from God, so it had to be done, or it could’ve also been self motivated, as they saw God as this all powerful, eternal being and they believed that if they believed that and wanted to achieve that powered, then everyone else should as well. 1391 in Spain was filled with an immense amount of conflict and destruction to relationships between the Christians and Jews. I think that this event is very significant to keep in mind, especially when continuing to study further into Spanish history as this event had a major impact on the many events that followed.

Bibliography

“In Support of the Trinity (mid-twelfth century).” Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim and Jewish Sources, Translated by Thomas E. Burman. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Irish, Maya Soifer. “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” The Medieval Roots of Antisemitism: Continuities and Discontinuities from the Middle Ages to the Present Day., Edited by Jonathon Abrams and Cordelia Heb. New York: Routledge. Pg. 306-319.

Nirenberg, David. “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation: Jews and Christians in Medieval Spain.” The American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 4. Oxford University Press, October 2002.

Nirenberg, David. “Mass Conversion and Genealogical Mentalities: Jews and Christians in Fifteenth Century Spain.” Past and Present, No. 174. 2002. Pg. 6-41.

Oeltjn, Natalie. “A converso confraternity in Majorca: La Novella Confariade Sant Miquel.” Jewish History, 24. Toronto, Canada: Springer Science and Business Media, 2010. Pg. 53-85.

[i] Maya Soifer Irish, “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” (New York: Routledge) 306.

[ii] Maya Soifer Irish, “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” (New York: Routledge) 306.

[iii] Maya Soifer Irish, “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” (New York: Routledge) 306.

[iv] Maya Soifer Irish, “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” (New York: Routledge) 306.

[v] David Nirenberg, “Mass Conversion and Genealogical Mentalities: Jews and Christians in Fifteenth Century Spain,” (Past and Present, 2002) 6.

[vi] David Nirenberg, “Mass Conversion and Genealogical Mentalities: Jews and Christians in Fifteenth Century Spain,” (Past and Present, 2002) 12.

[vii] Maya Soifer Irish, “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” (New York: Routledge) 307.

[viii] Maya Soifer Irish, “Towards 1391: The Anti-Jewish Preaching of Ferran Martinez in Seville.” (New York: Routledge) 307.

[ix] David Nirenberg, “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation: Jews and Christians in Medieval Spain,” (Oxford University Press, October 2002) 1066.

[x] David Nirenberg, “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation: Jews and Christians in Medieval Spain,” (Oxford University Press, October 2002) 1066.

[xi] Natalie Oeltjen, “A converso confraternity in Majorca: La Novella Confariade Sant Miquel,” (Toronto, Canada: Springer Science and Business Media, 2010) 68.

[xii] “In Support of the Trinity (mid-twelfth century),” (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) 195.

[xiii] “In Support of the Trinity (mid-twelfth century),” (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012) 195.

]]>Following the collapse of the Visigothic Kingdom in Iberia to the Muslim invaders from Maghreb at the start of the 8th century a new series of polities would begin to emerge in the region of Iberia north of the Cantabrian mountains that would eventually grow to encompass the rest of the peninsula throughout the next several centuries. With such a rapid shift in power structures and relationships with the establishment of Al-Andalus new Christian rulers used a variety of tactics besides military conquest and religious means in order to create a new base of legitimacy and authority for themselves such as bending trade, legal infrastructure, local cultural customs and their own personal dynastic histories. These methods laid the foundations for new rulers to exercise their authority over a volatile and constantly shifting political and cultural climate.

One of the primary and most unique methods through which the new dynasties of Christian rulers established themselves was through the use of dynastic chronicles, focusing on the Chronicle of Alfonso III in this instance. As it stands presently, there are extremely limited sources detailing exactly what transpired in the region that gave rise to the Kingdom of Asturias immediately following the Muslim invasion during the early to mid-8th-century. Seemingly, one of the best sources for this time period is a series of chronicles written during the following two centuries detailing the primary actors in the region and their accomplishments. However, upon closer inspection there begins to arise a pattern in the ways this turbulent period is described by those looking back on it. These chronicles can be considered as primary sources not for the 8th century in which they most detail, but for how the people of the 20th century viewed and made sense of the events of the 8th century. To be even more specific, the “people” refers to those who were involved in its creation, namely the namesake of this particular chronicle, King Alfonso III and his court who are the most likely authors. The Chronicle of Alfonso III specifically details a line of kings beginning with Visigothic Kings of the 7th century and ending with Alfonso III himself, with one of its main focuses being on the exploits of a certain King Alfonso I, who of which there is very little corroborating evidence to have actually existed (Rosenwein 2018). To establish some context, Alfonso III did much to expand the small pocket that was his Kingdom of Asturias, so much so that not only was the kingdom able to be split into 3 separate realms upon his death amongst his sons, but his reign also began a strong cultural and religious link to the more powerful Christian realms to the north-east. This expansion necessitated a greater degree of control, and thus Alfonso III likely sought for was to increase his standing amongst his subjects. By this avenue of thinking, it has be theorized that Alfonso I had either had his life greatly exaggerated or had been nearly completely fabricated in order to serve as a “discourse node” through which Alfonso III could garner legitimacy for his own reign (Escalona 2004). By establishing new characters that would serve as the ‘founders’ of the new realm, but also connecting himself to the Visigothic dynasties without needing to bear the liabilities for their swift defeat at the hands of the Muslims Alfonso III had created means through which to establish himself as a core pillar at the foundation of his burgeoning kingdom.

Another way the Christian kings established themselves and their authority throughout their growing realms was through the different legal systems of each realm. Following similar inheritance laws as the Visigoths, the splitting of the realm of Alfonso III started the trend of fracturing kingdoms that would go one to develop unique systems of governance, as evidenced by the vastly different systems in place in Castile and the Crown of Aragon for instance. As time progressed and so did the expansion of the Christian kingdoms, the county of Castile evolved into the most powerful polity in Iberia and understanding the internal structures that allowed this to come about is critical for understanding the future of the Spanish kingdom. As Castile grows and its presence becomes more and more prominent in Iberia its impact on trade and resulting influence the monarch had on regulating trade became more and more intertwined with the realm laws of Castile- particularly during the rule of Alfonso VIII, as we can see the changes undergone since the times of Alfonso III and how the new territories and its associated peoples and resources came to impact the kingdom during a shift in the balance of power of Iberia away from Al-Andalus (Rosenwein 2018). For an earlier example, one can look to an exchange charter in the earlier kingdom of Asturias-Leon. Asturias-Leon emerged from the conflict between brothers following the death of Alfonso III when these two realms were originally split, and while not comparable to exchange charters of other Christian realms at the time in size, the data present particularly in regard to transactions between lay people give a glimpse into how the wider developments of the realm from both external (territory gain, conquest, etc.) and internal (monarch authority, religious matters, cultural and technological developments) factors affect the primary subjects of a Christian realm in Iberia (Davies 2019).

The economic prosperity of the realm certainly keeps a ruler’s position stable, but when changes need to be made a power exercised a ruler with no effective control over the state apparatus will not be able to inflict their will. In the reverse sense, rulers needing to expand their legitimacy and control over newly conquered lands, territory under control of powerful nobles with entrenched traditions, or just another ethnic group have made use of the legal and justice system to expand their authority. While it was difficult for rulers to truly ruler directly until later into the early modern era, medieval Iberian kings made use of judges that would only be acting on behalf of the king (Viso 2017). One of the most important institutions for rulers was the Cortes in which a large gathering of subjects representing different classes could petition the king and he could respond in kind with direct decrees. While it may seem to be a mechanism for the populace to better communicate their concerns to the monarch, no other system could have allowed the ruler to directly impose his will on most of his most important subjects so efficiently.

A final example of an element that monarchs used to lay the foundations for new realms was in the unique cultural practices from north of the Cantabrian Mountains. While prior to the Muslim invasion Christians had been spread all throughout Iberia, the kingdoms that would develop into Spain and Portugal had their beginnings in the Kingdom of Asturias, which was isolated to the relatively small and isolated northern region of what we would also call Asturias today. The fact that the only independent Christian realm was limited to this area for more than a century can narrow down our field of research when analyzing those time periods such as the 8th century when there are very little primary documents. This cultural focus on the mountainous territory means that the locations of settlements and eventually cities has remained relatively unchanged through the ages (Cortina and Díaz-Guardamino 2015).

By analyzing contemporary documents and researching the contexts in which they were written combined with modern analyses can give us a clear picture on the different methods of that Christian Iberian kings used to establish not only their own rule but propping up their growing realms in a turbulent time. The benefits of understanding the structures behind the rise of the new Christian kingdoms lies not only in understanding the society of Iberia throughout the rest of history up to present, but also towards wider subjects such as the effect Spain and Portugal had on the events of colonialism during the early modern age and the following decolonialism trends which had global ramifications.

Works Cited

Cortina, Miguel Ángel de Blas, and Marta Díaz-Guardamino. 2015. Megaliths and Holy Places in the Genesis of the Kingdom of Asturias (North of Spain, Ad 718–910). The Lives of Prehistoric Monuments in Iron Age, Roman, and Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198724605.001.0001/isbn-9780198724605-book-part-18.

Davies, Wendy. 2019. Exchange Charters in the Kingdom of Asturias-León, 700–1000. Christian Spain and Portugal in the Early Middle Ages. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429326653-5.

Escalona, Julio. 2004. Family Memories. Inventing Alfonso I of Asturias. Brill Academic Publishers. https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/44838.

Rosenwein, Barbara H. 2018. Reading the Middle Ages: Sources from Europe, Byzantium, and the Islamic World, Second Edition. 3rd ed. University of Toronto Press.

Viso, Iñaki Martín. 2017. “Authority and Justice in the Formation of the Kingdom of Asturias–León.” Al-Masāq 29 (2): 114–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503110.2017.1349979.

]]>

Jewish Conversion to Christianity in Late Medieval Spain:

Women’s Reasons for Converting and the Effects That Followed

In the late medieval period in Spain, there were a myriad of reasons that Jews converted to Christianity. This paper will focus on why Jewish women sought out conversion and how converting affected conversas (female word for convert). Paola Tartakoff highlighted that Jewish women converted under two broad sets of circumstances: “some went over to Christianity with their husbands or fathers, while others chose baptism in order to assert control over their lives”[1]. Conversions were hardly ever forced; however, coercion from extraneous factors were often contributors. Women who converted with their husbands and fathers seemed to do so out of necessity, whether that be for protecting their inheritance and dowry, or for protection against prosecution in the future. On the other hand, baptising to gain autonomy can be seen in many factors for conversion. Violence against Jewish people in 1391 resulted in mass conversion in the years to follow[2]. Some women chose to convert for issues involving marriage (wanting to marry or divorce). Additionally, some baptized to seek economic relief in a time where Jewish communities were facing extreme financial issues[3].

Even when conversion was sought after to escape dire situations, what followed after baptism was not vastly superior. Apostates faced various struggles after baptism. Most struggled with poverty after renouncing Judaism, leaving them dependant on Christian charity[4]. Some conversas who were coerced into conversion were forced to present as Christians in public but practiced Judaism secretly. While some apostates did so, not everyone did; nonetheless, the danger of being accused or caught of Judaizing a common concern as it could result in severe punishment[5]. Christians were suspicious of the converts because they did not know who was being unfaithful, and many Jews viewed the converts as traitors and sinners[6]. Tensions from both groups left the converts in an uneasy situation.

Conversion

1391 was filled with violent raids against Jewish people in Castile and the Crown of Aragon following the deaths of King Juan I and the archbishop of Seville, Pedro Gómez, in 1390[7]. Both were attacked for being “Jew-sympathisers’, so following their demise, Ferrán Martinez magnified anti-Jewish preaching, leading to the riots[8]. This brutality reached Girona in August, led to mass conversions, the death of about 40 Jews, and the destruction of the Jewish community[9]. The majority of the Jewish community survived by escaping to Gironella tower, a refuge where they stayed for several months[10]. While technically safe, the living conditions were less than desirable, and many Jews converted starting August 10[11], possibly to escape the conditions of the tower[12]. Life for the Jewish people in Girona did not improve after 1391 as economic burdens began to escalate in the years to follow[13].