| CARVIEW |

I disappeared again – I’m sorry.

I’m trying to decide whether I’m done with this whole blogging malarky – there are aspects I miss – but I get overwhelmed with the effort it takes me now. So, if I do stick around, I might need to change the kinds of posts I publish and focus less on the long review posts I used to write, and would prefer to write if I could. I will return to reading other people’s blog posts when I can and just see how I feel over the next couple of months.

So here’s some reading highlights from the last few weeks.

Months ago I was fortunate enough to to be sent a review copy of Small Bomb at Dimperly (2024) by Lissa Evans. It was something to look forward to having so enjoyed her previous novels, Crooked Heart, Old Baggage and V for Victory. This novel introduces some new characters, set just as WW2 comes to an end. Corporal Valentine Vere-Thissett, finds himself a reluctant heir to a dilapidated estate. The house filled with assorted relatives and dusty taxidermy. Zena Baxter, working as secretary to Valentine’s eccentric old uncle, has fallen in love with the place – it’s a million miles from where she lived in London before she was evacuated as an expectant mother. Now her little daughter runs around the gardens happily and Zena is loath to return to London. This was such an excellent read – great characterisation and a brilliant setting.

My feminist book group chose to read The Holiday Friend (1972) by Pamela Hansford Johnson for our September discussion. It was a thoroughly engrossing read – one of PHJ’s later novels, it has a very seventies feel in parts – though, my group did all think that it could easily have been set/written twenty or thirty years earlier. Gavin and Hannah Eastwood are a very happily married couple on holiday on the Belgian coast with their very overprotected son Giles – who is nearly twelve. Melissa – a young student of Gavin’s is also in the village, staying at a much cheaper hotel – she deliberately followed the family, having decided that she is hopelessly in love with Gavin. There are several fascinating things here – the dynamics between everyone being the main one. This is a less humorous novel than some of PHJ’s more satirical novels, it’s much darker – and the ending is quite extraordinary. The author really leads the reader up the garden path.

My most recent read in my Margaret Drabble reading of 2024 The Witch of Exmoor (1996) was another hit. I continue to enjoy Drabble enormously. This is a complex literary novel – though I must say I find Margaret Drabble so readable – she’s worth spending a little more time on. This novel is about an elderly, eccentric writer and her three rather grasping adult children. It was a wonderfully sharply observed tale.

My most memorable real page turners I would say were Appointment with Yesterday (1972) by Celia Fremilin and Late and Soon (1943) by E M Delafield. Fremlin is just a master of atmosphere and I was obliged to sit up late with this one. It tells the story of a woman who arrives in a small seaside town with just a small amount of money in her pocket and no luggage – operating under an assumed name she is running from something that happened in the home she shared with her second husband. She spends her first night on a bench on the prom, determined to find a job and accommodation the following day. She’s terrified of the shadow that hangs over her – and gradually as she begins work as a daily help and gets a room in a lodging house, we see in flashback the life she had been living before. Trapped in a dark, claustrophobic basement flat, struggling to cope with the paranoid delusions of her new husband.

E M Delafield is less heart stopping perhaps – but just as compelling. Valentine Arbell is a middle aged widow living with her brother – and younger daughter in a large uncomfortable country house. Her eldest daughter lives in London, and rarely visits. When Colonel Lonergan is given a billet in her house she is delighted to find he is her old teenage flame. The relationship that inevitably reignites, is complicated by the fact Lonergan has had a relationship with Valentine’s older daughter Primrose, a cold, sneering young woman whose biting sarcasm is especially aimed at her mother.

A couple of other recent reads include The British Library women’s writers collection of stories Stories for Summer (2024) which contains stories by all the kinds of writers I love. Cat’s Eye (1988) by Margaret Atwood – a reread after more than thirty years, I had forgotten what a long book it was. I read on Kindle. A brilliant evocation of childhood, exploring, art, memory and perception. I am looking forward to discussing it with my book group next week. I treated myself to the hardback of The Hazlebourne Ladies Motorcycle and Flying Club (2024) by Helen Simonson. Set just after the end of WW1, it’s a thoroughly entertaining read, with lots of brilliant feisty female characters and Simonson does quite well in showing how women had to fight to retain the small bits of independence they had begun to get during WW1 and were already beginning to lose.

Well I have worn myself out, so I will end it there. I hope I will be back soon – but if you don’t hear from me don’t worry, I’ll just be hiding again.

]]>

Hello! I am dipping my toe back in the water – just to see how it feels.

My last post on Heavenali was in mid June, and at the beginning of July I stopped reading other blog posts and announced on social media that I would be taking a break. Although I didn’t put a time scale on it – I had the vague idea of coming back at the end of August/beginning of September. A complete break from both writing and reading blog posts was necessary because I had suddenly become totally overwhelmed with it. Coming back I doubt I will be blogging any more often – but I need to reignite my enthusiasm. Fellow bloggers I will start to read your blog posts again – although finding time and energy to do that has become one of the hardest things for me oddly enough.

So what have I been doing/reading since the middle of June? I have been reading mainly fiction, as usual – but quite a range of things within that. There have been light fiction, literary fiction, older and new books, translated fiction, kindle books rereads and even a tiny book of poetry. I think I can honestly say I have been enjoying my reading over the past couple of months – and it has been lovely just reading, not thinking about whether I was going to write about a book I was reading or not.

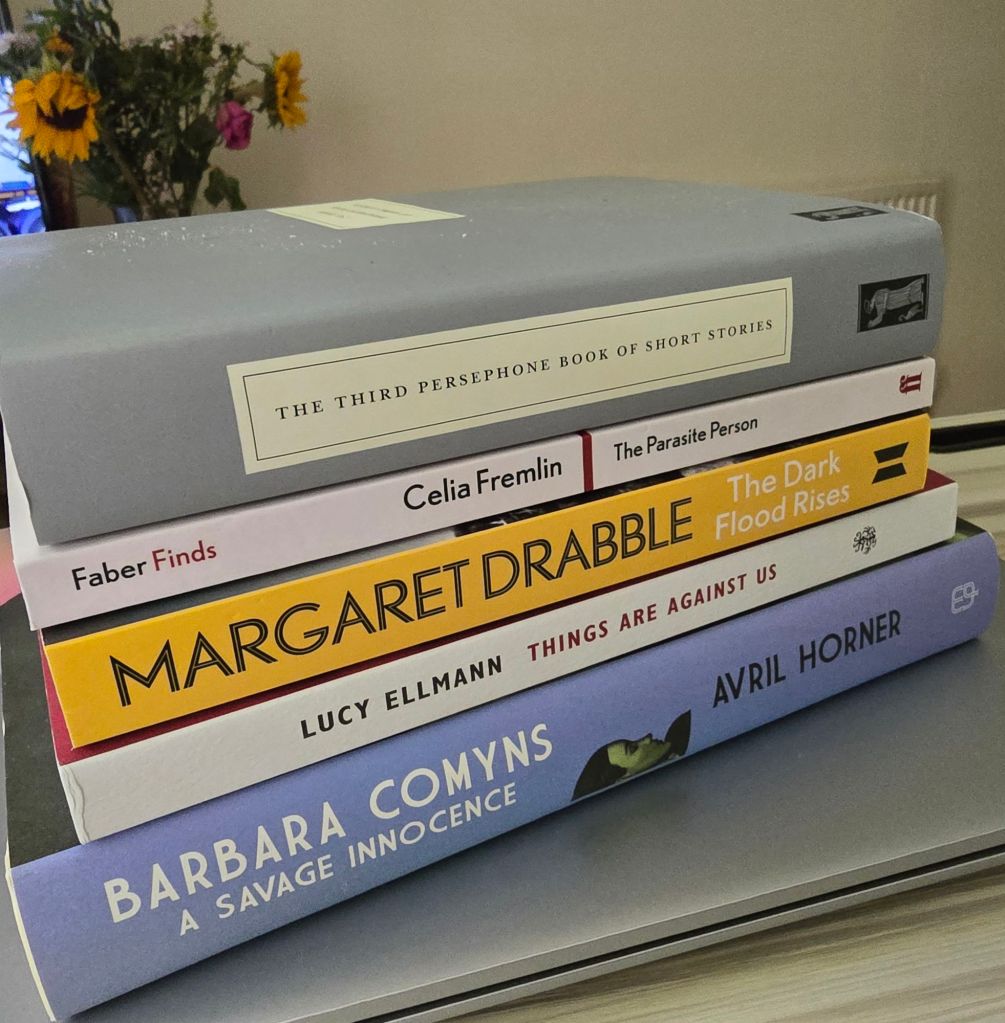

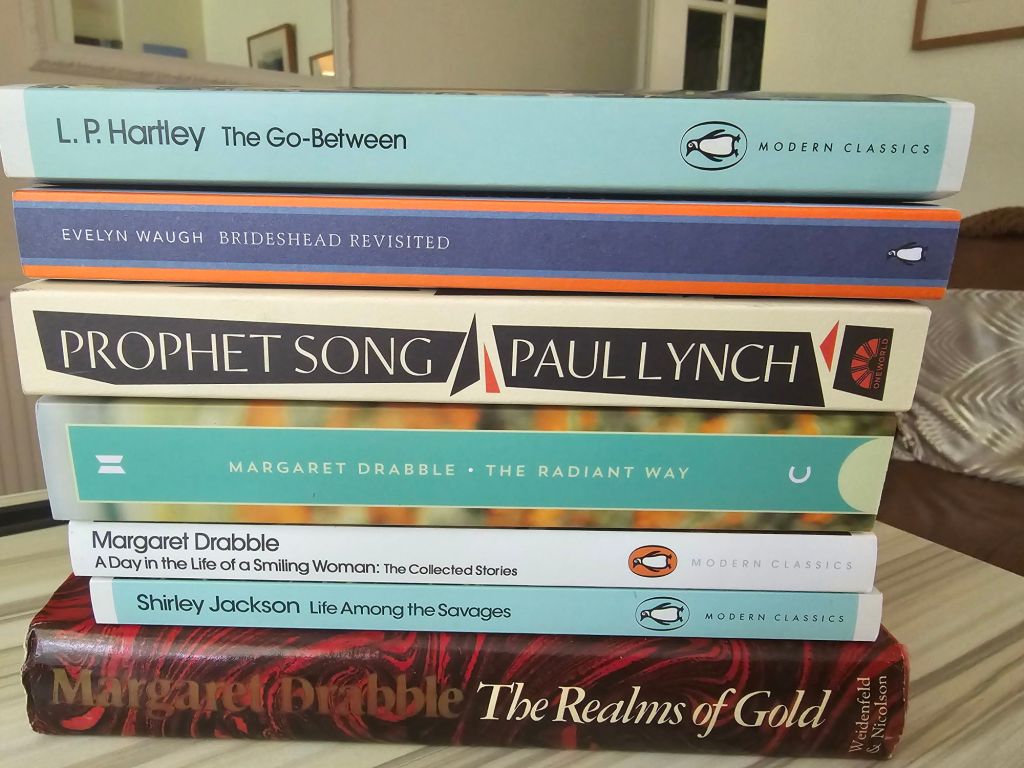

I have continued with my Margaret Drabble reading – which has proved a huge joy this year – I continue to be impressed with Drabble’s fierce intelligence, her books are literary, and sometimes complex and yet I find myself drawn more and more to her novels. I read A Day in the Life of a Smiling Woman – a collection of stories that was published in 2011 but contains stories written across a period spanning about forty years. The Radiant Way – three friends who first met at Cambridge negotiate the first few years of the Thatcher era facing personal and professional challenges. A Natural Curiosity is the second book in the Radiant Way trilogy so that was next – and was my favourite of the trilogy. I read the third book The Gates of Ivory a couple of weeks ago – a really ambitious novel set in London, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, which I really enjoyed spending time with. What an extraordinary writer Drabble is.

When reading such complex literary novels it’s sometimes necessary to dig out some lighter palate cleansers. My WI virtual book group tends to pick lighter books. I read Dear Mrs Bird by A J Pearce with them, and The Invisible Woman’s Club by Helen Paris. I wasn’t that impressed by Dear Mrs Bird which I had expected to really like, but definitely liked The Invisible Women’s Club – a book about older women, gardening, friendship and a campaign to save some allotments. I read it during a very difficult week in the UK – news wise – and it provided something like a soothing balm to my sad heart. There was about a fortnight when I could barely look at social media and I needed nice books to read. I also read the British Library’s Death of a Bookseller – another good piece of escapism, with some lovely bookish details. I finally read Before the Coffee Gets Cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi, a whimsical Japanese novel that has been hugely popular. Not my usual thing perhaps, but I really liked it. I also finally got around to reading my first book by Claire Fuller who I had heard such good things about. I read Unsettled Ground, which was a darker novel than I realised but I enjoyed Fuller’s depiction of marginalised people living on the edge of society.

My other book group, the feminist book group which is also now virtual, has been reading some excellent books. Some of the choices recently have been rereads for me – and at least one of the ones coming up will be too. In June I reread The Spare Room by Helen Garner. It’s a beautiful thoughtful novel – Garner is particularly good at not presenting either of the two female protagonists as a hero or villain, there’s no sentimentality, just raw honesty. Our July read was The Wren, the Wren by Anne Enright – I didn’t dislike it exactly, but I was definitely underwhelmed, it took a while to get into and there were characters I wish we had had more of. It made for an interesting discussion though. Our August read was The Crowded Street by Winifred Holtby – it was my third reading of this 1924 feminist classic and I loved it all over again, in fact it was probably my favourite reading of it.

August is Women in Translation month – and I wanted to join in a bit even though I wasn’t writing blog posts. I began August reading Claudine at School by Colette on my Kindle – even though I had recently bought a pile of old Colette books on ebay. Those other Colette books are definitely calling to me though. I read Premonition, my first novel by Banana Yoshimoto which I thoroughly enjoyed. A much tougher read for Witmonth however was A Woman in Berlin, by an Anonymous German woman, it’s a tough, fairly uncompromising account of about eight weeks in 1945, when the Russians took over Berlin. I then read The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson which was so good, a slighter darker story than others by Jansson I have read, but beautifully written.

Some other fantastic vintage reads include The Fly on the Wheel by Katherine Cecil Thurston, which was originally sent to me by Kaggsy, a reread of The Go-Between by L P Hartley, None Turn Back by Storm Jameson, Nothing is Safe by E M Delafield which I read in a day and Out of the Window a Persephone book I simply couldn’t put down.

Aside from reading I have been trying to get out a little more often – there have been a few outings with the help of friends and family. My new powerchair is heavy and needs two people to lift in and out of cars, but it has been lovely going to local parks and a National Trust property – recently meeting up with other wheelchair users in a local park, on a day the sun actually shone. I spent a lot of August watching the Olympics and I haven’t stopped indulging in my love of world drama – and this past week I have got my jigsaw board out again.

So I am tentatively saying, I’m back, I’m reading a book which I hope will be my first proper book review in more than two months. I hope you’re all well and the books have treated you well, I look forward to catching up with some of you soon via my blog reader.

]]>

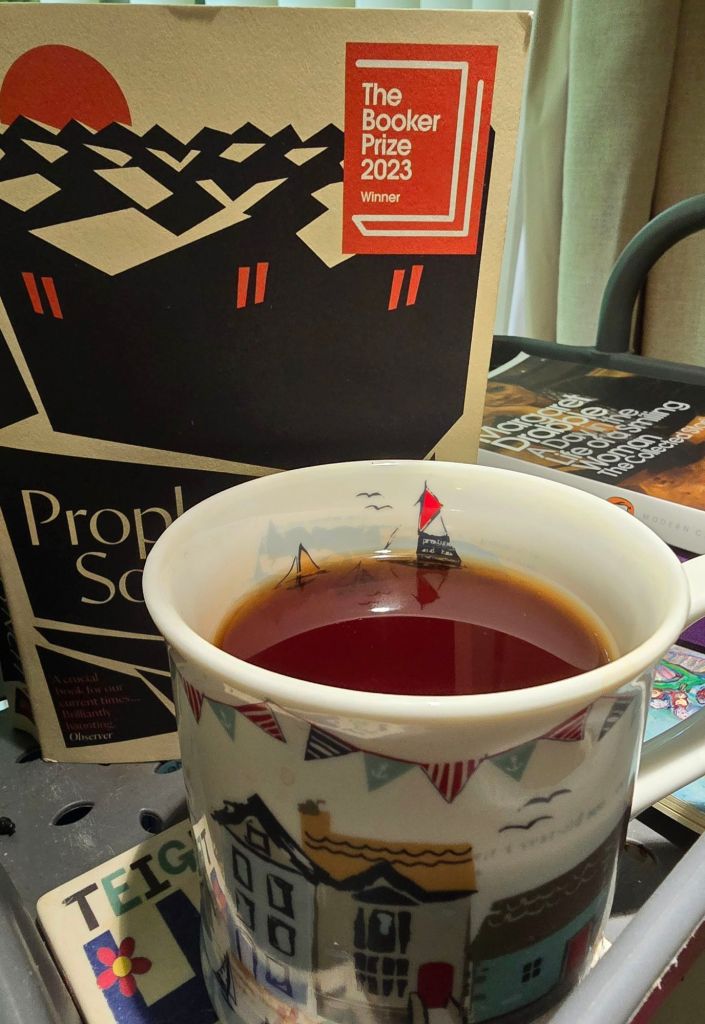

Last year’s Booker Winner Prophet Song has been on my radar to read ever since it was longlisted last year. Typically, I have only got around to buying myself a copy recently.

I thought it was an incredibly powerful novel, hugely thought-provoking too, to the extent that I found myself thinking about it even while I wasn’t actually reading it. It’s a dystopian novel, chillingly told – of a society on the brink. It’s rather depressing, truth be told, because these things or things very like it have already happened in countries such as Syria – only here the country is Ireland – and suddenly we can see ourselves in these events and the view is rather terrifying. It’s so easy to imagine that such things take place in other places far removed from Western Europe, America, Canada etc – if we choose to be complacent (and many of us do not, at all) we could feel safe from such terror – but should we? Having said that – I just couldn’t stop reading, or thinking about it.

“and the prophet sings not of the end of the world but of what has been done and what will be done and what is being done to some but not others, that the world is always ending over and over again in one place but not another and that the end of the world is always a local event, it comes to your country and visits your town and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news, an echo of events that has passed into folklore,”

Most reviews I have seen of this novel state that it is set in a near future Ireland, although in an interview I saw with the author on YouTube he insisted that nowhere in the novel is the period revealed – which is the case, I don’t know what to take from that, as I had assumed that it was set in the near future. Certainly this is a very recognisable world, a world of ordinary suburban houses, families juggling work, children and household tasks.

Much has probably already been said about the style of this novel. It is written in large blocks of text with no paragraphs and no speech marks. I would say don’t let that put you off – I know not everyone likes that kind of style. There are frequent page breaks – every three or four pages which I think help make the look of the text less dauntingly dense. However, I didn’t find this a difficult book to read at all – I found the style lends itself to the compelling nature of the story, and the poetic, brilliant language is a real pleasure to read. The author never allows us to become confused in who is speaking and the whole narrative flows beautifully and uninterruptedly to its conclusion. I enjoyed the rhythm of the language and I can absolutely see why it won the Booker.

From the outset this is a heartstopping story. It begins on a wet Dublin evening, when Ellish Stack, a scientist and mother of four is brought to the front door. Two officers from the GNSB, Ireland’s newly formed secret police, ask to speak to her husband, a teacher and trade unionist. Ireland has recently undergone great change, a new government is driving the country toward tyranny. Everything familiar is slowly starting to disappear. First her husband disappears – vanished into a silent, secret world, others in the country are also starting to disappear. Protests are quickly and often brutally quashed. People at work begin to look at Ellish differently, it might not be safe to discuss certain topics over the phone, the state now controls the TV news. Ellish tries to shield her children from the reality of what is happening but it quickly becomes apparent that she can’t – her older children, around sixteen, fourteen and twelve (there’s also a baby) can’t help but be affected by the atmosphere around them, their mother’s fear – their father’s absence, the curfew and their favourite foods disappearing from the shops. Her daughter Molly becomes frightened and silent, her son Bailey begins to wet the bed – his rage is a white hot fury of confusion and terror. As her eldest son Mark nears his seventeenth birthday there is another fear – that her bright, ambitious boy will be forced to join the army, Ellish decides to hide him, enlisting the help of another woman who’s husband has also disappeared. However, Mark decides to join the rebel forces fighting to overthrow the government – and he too disappears into a world of silence and fighting.

Ellish’s elderly father lives nearby, he seems to be in the early stages of some unspecified dementia, but he has sudden moments of clear sighted clarity – but his vulnerabilities give Ellish someone else to worry about as he refuses to go to live with her and the children. We sense the world watching events unfold, holding its breath, shaking its head in disbelief. Ellish’s sister in Canada, urges her to flee – sending a large sum of money to help bribe her family’s way out of the country. However, Ellish can’t bear to leave her husband and eldest son behind her – insists on believing that things can’t stay like this for long – not in her country.

“History is a silent record of people who could not leave, it is a record of those who did not have a choice, you cannot leave when you have nowhere to go and have not the means to go there, you cannot leave when your children cannot get a passport, cannot go when your feet are rooted in the earth and to leave means tearing off your feet.”

It becomes clear that the country is becoming more and more divided. More and more people proudly wear the badge of the ruling party showing where their allegiances lie – while others protest or send their sons to join the rebels. Many people hide in their homes, listening to the battle for freedom going on above their heads, in suburban communities of Ireland – it is almost unimaginable. Only, it isn’t really, we have seen it all before – and we see how quickly fear encourages people to turn away from who they used to be, creating division and suspicion everywhere.

“if you say one thing is another thing and you say it enough times, then it must be so, and if you keep saying it over and over people accept it as true – this is an old idea, of course, it really is nothing new, but you’re watching it happen in your own time and not in a book.”

I don’t want to say too much more about the actual plot – but it is quite the rollercoaster – and this ordinary family is changed forever in ways hard to imagine. I thought this was a quite brilliant novel – and I am so glad I finally got around to reading it.

]]>

One of the reasons I chose to give myself a little reading project for 2024, was to help revitalise my enthusiasm for blogging. Although I read slower than I once did, my enthusiasm for that at least has never waned. Writing about the books I read has become more of an issue. However, despite my enjoyment of my Margaret Drabble reading this year – I haven’t even managed to write about all of the books I’ve read in full. The Realms of Gold was one of the books I read in May that I most wanted to write about. It’s a fairly complex novel – though not especially difficult to read, so I only hope I can do it some justice. It was an easy five star read for me, layers of brilliance and multiple themes with a strong, likeable heroine.

Frances Wingate is a successful archeologist, divorced with children, she has recently separated from her married lover Karel – despite knowing she loves him. The novel opens as Frances is abroad to deliver a lecture at an academic conference. Alone in her hotel room she remembers her relationship with Karel and their parting a few months earlier – willing him to come back to her. Karel’s marriage is very unhappy, and Frances believes Karel and she should be together, and yet, she ended their relationship almost on a whim. There’s a flashback to a rather unpleasant incident between Karel and his wife, which shows him ‘beating her up’ in frustrated fury – no doubt, it is indicative of the 1970s, that we are supposed to see this as a forgivable one off by a man driven to distraction and deeply unhappy. There are some things in books that don’t stand the test of time so well. There are a few sections of the novel told from Karel’s POV and he is a pretty decent guy, nothing like the above incident might suggest – it’s the kind of thing that is confusing for modern readers. Things like this don’t spoil books for me, they give me something else to think about – the wider context being a sociological one perhaps. There’s another male character in the book who is far more problematic – there’s no suggestion of violence, yet Drabble portrays him as controlling and difficult with chilling accuracy. I find the difference in Drabble’s own attitude to these men quite interesting.

Frances frequently suffers bouts of depression, depression we discover runs in the family, but Frances has learned to live it with, clawing her way out of it bit by bit.

“She still didn’t feel exactly cheerful, though the worst was over. She walked up and down for half an hour or more, muttering to herself, trying to divert the energy of the experience to some more useful end, but she was exhausted. It was, after all, as though some bad weather had passed over her, leaving her a little flattened, like a field after heavy rain. It would take her some time to shake it off and slowly uncrackle and unfurl herself again. Meanwhile, she walked up and down, and had another drink.”

Frances is a real grown up, she’s a strong, intelligent woman, who manages her career and four children with seeming ease. Her work focuses a lot on landscape and she has some passionate beliefs in the importance of landscape for the civilisations of the past. Some of the themes of this novel involve revealing the truths of the past, civilizations and their rituals, like marriage or funeral rites, the raising of children and supporting other relatives.

“Too much of the world was inhospitable, intractable… Why prove that it had ever once been green?”

Before flying home, Frances decides to send Karel a postcard telling him she loves him, sure that the mere sight of it will bring him back to her. There has been a postal strike in the country where the conference is being held but Frances doesn’t take that into account at all. Once at home she resumes her usual normal family life – waiting for Karel to get in touch. She visits her parents, and her brother, who has struggled with depression, and solved it with drink. She worries about her nephew Stephen who has found himself with a wife and baby while still very young, and with his wife hospitalised for a mental health condition, he is trying to manage everything on his own. In time we see Frances was right to be concerned. There is another academic conference on the horizon, and by the time she leaves, she still hasn’t heard from Karel.

Interestingly, we also get a glimpse of some of Frances’ unknown relatives in the East Midlands. David; a distant cousin, is a geologist, working very much within the same world as Frances; he is in the audience when she gives her speech at the start of the novel As Frances still uses her married name, he has no idea of the family connection, and it isn’t until later in the novel, at another academic conference in Africa that they finally meet. Frances makes a kind of pilgrimage to the rural East Midlands town of Tockley where she and her brother holidayed as children, not realising there is a cousin living just down the road who she passes in the street. We meet this cousin, Janet, living in what feels like a small, stifling Lincolnshire town, coping with the rigours of a young baby, married to a rather horrible, slightly controlling man, (who I referred to above) who is virtually no help at all, and has stripped away any confidence that Janet might have once had, she dislikes sex and tries to avoid his nightly, advances.

“Her neighbour was a constant threat to her, and she would avoid encounters if she possibly could. It was not that there was anything overtly threatening about her – on the contrary, it was her very meekness that constituted the menace. She was an awful warning, – poor Jean Cooper, of what Janet herself so nearly was timid, nervous, gauche, sad, unfinished. She lived in the downstairs flat of the house next door, with her silent husband, and she was going mad, Janet thought, from boredom, so mad that she would even overcome her shyness to talk endlessly, nervously, over the garden hedge.”

Later, when an unexpected family crisis brings her home from the African conference early, Frances meets Janet, and on meeting the husband, knows just what kind of man he is.

Drabble weaves all these strands together brilliantly, her world becomes immersive and Frances was a pleasure to spend time with. What a fascinating writer Margaret Drabble is.

]]>

I have not had a particularly good blogging month – I seem to be saying that every month this year. I keep promising myself that I will write more reviews and then failing to do so. Blogging aside, I have enjoyed this month of reading. I don’t seem to be increasing the amount I read, but I’m really not bothered about that any more. I read some thoroughly immersive and compelling books this month.So, I would like to try and give a little flavour of all those books I have failed to review below.

It was only last month that I read the third Richard Osman book. My virtual WI bok group had chosen to read The Last Devil to Die (2023) by Richard Osman, his fourth in the successful Thursday Murder Club series, so I found myself returning to these characters sooner than I might otherwise have done. It was the only book I read on Kindle this month too. This novel continues several of the threads from the previous books, including the relationships of the two police officers and the story of Elizabeth’s husband Stephen – who is suffering some form of dementia. This is definitely the best book of the four – written with real warmth, it is surprisingly poignant, with a clear sense of everyone getting older, things changing and moving on. I believe Osman is taking a break from this series to concentrate on a new series, and this does seem to be a good place to leave everyone.

I heard about the novel Twice Lost (1960) by Phyllis Paul on another blog – and immediately bought a copy. Phyllis Paul is an English novelist who seems largely forgotten now despite having published a number of works between 1933 and 1967. Twice Lost is a slow burn, not a particularly quick read, I have seen it likened to The Turn of the Screw and Picnic at Hanging Rock, well I haven’t read the second of those, and I don’t really think it’s as dark as The Turn of the Screw. A child, Vivian Lambert disappears after a tennis party on a lovely summer day in an English village. Teengaer, Christine Grey is the last person to see Vivian, and is haunted by her disappearance for years after. Then, someone claiming to be the grown up Vivian appears and the mystery only deepens. Phyllis Paul makes the child Vivian unsympathetic, and the relationships between all the other characters are strange and dysfunctional. It’s a strange, unsettling novel, with a stifling, claustrophobic atmosphere.

Following on from that, Clothes-Pegs (1939) by Susan Scarlett reissued by Dean Street Press was a much lighter read. Annabel takes a job at a high end dressmaker’s in the sewing room, but is unexpectedly promoted to the role of ‘mannequin’ showing off the fine clothes to wealthy customers. Poor Annabel has to endure the cattiness of her fellow models, and when she catches the eye of Lord David de Bett she also unleashes the fury of the Honourable Octavia Glaye who has her own eye on David. A sweet comfort read, that reminded me a lot of Susan Scarlett’s Babbacombe’s – there’s a familiarity in the set up – but I enjoyed it nonetheless.

As I wanted to start the Comyns biography on my birthday, and I had finished Clothes-Pegs the afternoon before, I had to find something short for bedtime. On the Pottlecombe Cornice by (1908) Howard Sturgis fitted the bill. A tiny hardback novella from Michael Walmer. It’s really just a short story. Major Hankisson has retired to a little fishing village where a lovely new stretch of white road goes across the brow of the hill. Here is where the Major chooses to go walking, every day he sees a beautiful older woman, with whom he doesn’t speak, but enjoys seeing each day. He decides to find out what he can about her.

Long anticipated, and bought for me by Liz for my birthday Barbara Comyns – Savage Innocence (2024) by Avril Horner is the only book read in May that I have also reviewed, so I won’t repeat myself here. It was easily my book of the month.

With The Realms of Gold (1975) by Margaret Drabble I continued my Drabble reading. Another brilliant read, a complex, intelligently written immersive novel, quite a slow read, but one I loved spending time with. Frances Wingate is a successful archeologist, divorced with children, she has recently separated from her married lover Karel – despite knowing she loves him. The novel opens as Frances is abroad to deliver a lecture at a conference. Later she travels to an African country for a similar event. She ruminates on her time with Karel – willing him to come back to her. Meanwhile we get a glimpse of some of her unknown relatives in the East Midlands. Naturally all the strands come together in a novel about family, civilisations, rituals and landscape. I think this is the longest of the Drabble novels I have read so far and It’s a shame that this novel remains out of print. I’m considering reading some of her short stories in June.

One of the books I bought recently was calling to me from the tbr; Life Among the Savages (1953) by Shirley Jackson is a memoir of family life. It is quite simply a delight. The memoir opens as Shirley and her husband and their two eldest children move to an old house in Vermont. Jackson’s account is very funny, as she manages misbehaving children, domestic mayhem and a rather oblivious husband. Her children (two more will be born) are imaginative and quite exhausting just to read about. There are imaginary friends, two cats and a dog to add into the equation – it’s glorious. Happily there is a sequel called Raising Demons, which I have also now ordered.

Well it was only a matter of time before I re-read Who was Changed and Who was Dead (1954) by Barbara Comyns. I re-read Our Spoons Came from Woolworths last year – and I had promised I would re-read the rest of Comyn’s novels. Reading that wonderful biography has just spurred me on. It is a famously strange and macabre novel, the river floods, ducks swim through the drawing room, then villagers go mad, some of them dying rather gruesomely. It is also rather brilliant. Surely a novel that could only have been written by Barbara Comyns.

So that’s it. I am contemplating a couple of book group reads at the moment. My feminist book group will be reading Spare Room by Helen Garner – I read it years ago, but a re-read will be required, so will be buying a new copy. My virtual WI book group is going to be reading The Sealwoman’s Gift by Sally Magnusson, which I can’t quite decide whether I want to read or not, so I haven’t bought that yet either. I have decided I will probably read a collection of Margaret Drabble’s short stories in June, and I have also decided to read the books I have now rather than keep reading chronologically and buying new ones. Having decided that it’s quite likely I won’t stick to it. Everything else will be decided by my mood.

What have you been reading in May? and what are you looking forward to next?

]]>

If I wrote only one book review this month (that is now looking fairly certain) the book review I had to write was this one. Despite having another terrible month in blogging terms, I have enjoyed what I have been reading, and the highlight of the month has been this long awaited biography of one of my favourite writers. Liz and I had agreed some time ago that she would buy me this for my birthday, so that was why I didn’t read A Savage Innocence when it first came out in March – I think I rather enjoyed having it to look forward to. I actually managed to arrange my reading so that I could start it on the afternoon of my birthday – it felt like a treat in itself.

Barbara Comyns was a unique voice among the legion of twentieth century women writers that I have come to love. She stands out as being completely unlike anyone else, her deceptively straightforward, naive writing style, her childlike narrators who gradually reveal chilling realities, her sense of the macabre and the absurd. She has a delicious wry humour, delivered in a deadpan voice that disarms the reader, but also shields them from too much horror. Her life equipped her to understand the difficulties faced by women, the reality of poverty and child bearing. I have read all her books, and have come to love that uniqueness. I was looking forward to finding out more about the woman who wrote those books, and I wasn’t disappointed.

Barbara Comyns own life was every bit as extraordinary as her books – her life informed her writing as we see in this brilliantly researched biography. Avril Horner shows where we can see the parallels with Comyns’ own life in her fiction – using extracts from the books, her letters, diaries and tantalisingly some unpublished works to prove her links. It is a thorough, detailed and completely absorbing read for the Comyns fan. Horner is careful to only draw parallels with fiction and life where she can prove it, and is also clear to point out where Comyns’ work is wholly fictional. The many extracts throughout the biography are a complete delight, there is so much of Barbara’s own voice in this biography, it feels like a really truthful but affectionate portrait.

Barbara Comyns was born in 1907 in Bidford-on-Avon in Warwickshire, one of six children. Her father was a self made man, a Birmingham brewer who married a woman who was his social superior – at least according to her family. The family home was Bell Court, a manor house on the banks of the river Avon. Like many women of her class and generation, Barbara’s education was rather haphazard spending very little time in school, her education was mainly left to one of a series of governesses. As a young woman Barbara saw herself as an artist, setting out to study art and particularly sculpture. Writing was to come into her life much later – and she didn’t publish her first book until she was forty. As a young woman she was surrounded by artists and married to her first husband, a young artist – she enjoyed surrealism – which shows in her writing, and lived in grinding unromantic poverty, just like Sophia in Our Spoons Came from Woolworths.

Horner explores Comyns’ personal relationships which were rather complicated, she was married twice, had at least two other partners and her second child born while she was married to her first husband was not his child. While living with her partner Arthur Price she even sailed pretty close to the wind – legally speaking in some of her money making schemes – if nothing else we see Barbara as a survivor. Artist, dog breeder, piano restorer, antique dealer, housekeeper, landlord and writer and a woman who moved house continually – I lost track of the number of houses, and flats she lived in both here and in Spain (where she lived for eighteen years). We also meet Diana – a woman who Barbara had a long and volatile friendship with – she was married to one of Barbara’s former lovers, the man who was the father of her daughter Caroline.

Barbara’s second husband was Richard Comyns Carr, an MI6 officer who was good friends with Kim Philby – and may have lost his job because of that friendship. However Horner also makes some fascinating suggestions about Comyns’ Carr and the possibility he was still doing some work for MI6 while he was living in Spain with Barbara in the 1950s and 60s.

Horner examines how Barbara became the writer she was – she was first and foremost a voracious reader. Her writing life had many ups and downs. Her first book evolved out of telling her children stories of her own childhood to entertain them. She had her supporters, her husband and the writer Graham Greene among them, but she didn’t always find publishers for her novels. She divided opinion, and her book sales even when reviews were glowing weren’t huge. It was frustrating and led to Barbara doubting her own ability – and meant some books appeared only several years after they had first been written. Money was still often tight – and it was partly because of that, that she and Richard left England for Spain. There was some success later when Virago started to reissue her novels in the 1980s, it was the first time that Barbara felt successful – but how sad that it came so late. It seems to have been Barbara Comyns fate to fall in and out of fashion over the decades, I think all her novels should be in print – those of us who have struggled to find copies of The Skin Chairs and Out of the Red, into the Blue – know the pain of trying again and again to find reasonable priced copies of books we are desperate to read. I’m certain if they were all in print, then people would read them. Hopefully this biography will renew interest in Barbara Comyns which has grown over the last few years as other novels became more available through publishers like Virago and Daunt.

Barbara Comyns lived a hugely eventful and turbulent life and Avril Horner explores it with honesty and affection – this is a brilliantly compelling biography and I loved spending time with it. Of course it has made me want to reread all my Comyns books too.

]]>