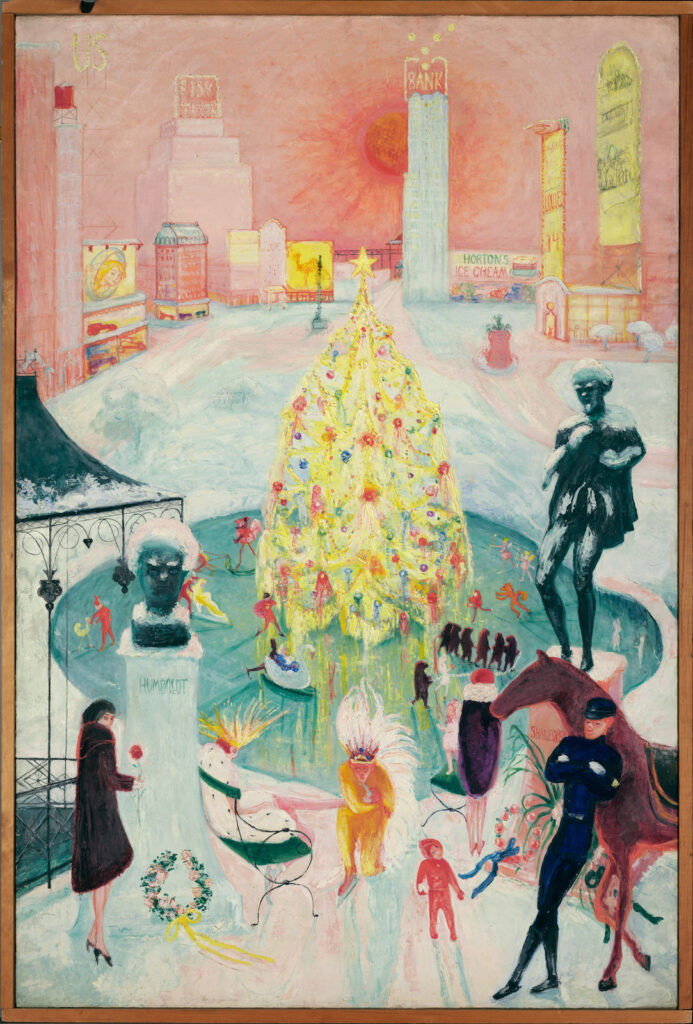

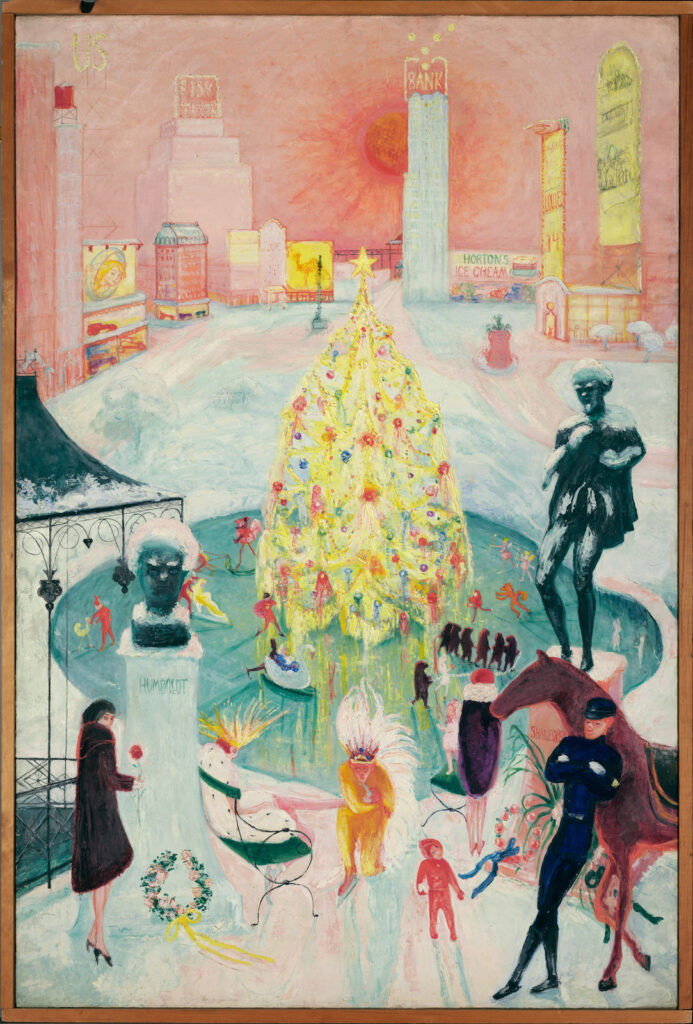

Painting is not photography, so the date of 1930-40 for a painting that includes a reference to a broadway show that only ran in 1925 is plausible, given other evidence. Merry Christmas and Happy Hannukah.

| CARVIEW |

the making of, by greg allen

Painting is not photography, so the date of 1930-40 for a painting that includes a reference to a broadway show that only ran in 1925 is plausible, given other evidence. Merry Christmas and Happy Hannukah.

While speedrunning through Soutines at Christie’s the other day, this popped up, Sherrie Levine’s 1984 watercolor of a Soutine that belonged to Melva Bucksbaum.

Of course, it’s not a watercolor of a Soutine, but a watercolor of a reproduction of a Soutine, yet another flattening step removed from the intense painterly construction of Soutine’s portrait.

The Aspen Museum had a whole show of early Sherrie Levine this past summer, and it’s worth remembering that rephotographing reproductions à la After Walker Evans was just one of Levine’s techniques for exploring the reproduction and circulation of images. Others included buying and framing posters of paintings; framed plates from art books; drew photos of drawings; and painted photos of paintings.

Back in the day, these watercolors were discussed in terms of their declarative absence of the original’s structure and painterly action, and as a thin, even surface on a thick paper ground. But they’re paintings of photos, so whatever flattening is there counts as documentation.

Anyway, I’m not finding a ton of stuff about Levine’s watercolors, nor of her exploration of Soutine. What I do see, though, makes me wonder why Bucksbaum, of all people, matted this picture this way, when it feels like it should be floated on its sheet.

Martin Herbert writing on Gerhard Richter for Apollo

For three decades, he could increasingly do anything, while coolly suggesting that perhaps none of it mattered in the grand scheme of things, even as his paintings also persistently whispered that maybe it did. Like so much great art, his can be endlessly revisited due to its fathoms-deep ambiguity. Look at an earlyish, unassuming canvas like Bridge (at the Seaside) (1969): a spit of land and outstretching bridge forming a horizon line under a delicately blueing, star-dotted evening sky, nobody around, the lower half fuzzily ambiguous: maybe it’s water, maybe beach, maybe half of each. Here is a casual, banal, snapshot-style update of the German landscape tradition, a knowingly minor thing. Yet it’s also somehow hushed and beautiful, almost tender—everything and nothing swirling together for you to tease apart or accept, finally, as indivisible.

I had wanted to avoid exhausted, but maybe I need to get to the Fondation Louis Vuitton Richter retrospective after all, for the acceptance of indivisibility

Gerhard Richter at Full Scale [apollo-magazine]

Chaïm Soutine was one of the first artists I found instead of being taught, and I am still enthralled by the intense, uphoved world of his paintings. [His real life, kind of a bummer, tbqh.]

Anyway, after @pg5-ish reblogged Soutine’s Two Children on a Tree Trunk (1942-3) into my tumblr dashboard this morning, I went looking for it, and found instead this great little painting of an unsettled little guy, which sold at Christie’s in 2016.

As I read I found myself flagging more and more paragraphs to quote here from David Velasco’s Equator essay, “How Gaza Broke The Art World.” The whole surreally infuriating scene with Klaus at the opening of Nan Goldin’s retrospective at the Neue Nationalgalerie? The whole Artforum debacle? The fracture of our collective illusions about the art world? Then Sam McKinniss’s Nan Goldin’s Press Conference (2025) scrolled by, and now I can say just go read the whole thing.

Sorry, Mark Rothko’s late paintings, there’s a new annoying read of art as foreshadowing kid in town. Victor Brauner’s 1931 self-portrait has been on the Pompidou’s Surrealism anniversary world tour for a while now, and is currently on view at THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART, where Andrew Wasserman photographed it yesterday, at a distance that hopefully doesn’t need a content warning.

The wall label reads, “Victor Brauner lost his left eye in an accident in 1938. Seven years before, curiously, he had made this small self-portrait with a removed eye, which now acquired the aura of prophecy. Brauner accepted his partial loss of physical sight, saying it had turned him into a seer.”

Which is still more circumspect than the Pompidou—who owns the painting but does not publish it, apparently—which calls the painting a “premonition,” and the foundation of Brauner’s surrealist cred: “cette œuvre occupe une place symbolique dans la vie et la création de Victor Brauner, annonçant l’accident qui le frappa lors d’une rixe entre Óscar Domínguez et Esteban Francès, dans la nuit du 27 au 28 août 1938, et qui le priva définitivement de son œil gauche (l’œil droit dans le tableau).”

So some things here: the accident was a bar fight between two other artists, and the eye Brauner actually lost was not the one missing in the painting. Losing his eye had an understandably large impact on the artist and his life and practice, well beyond the symbolic. The allure of using art to make sense of such a loss is also understandable.

The Pompidou’s text mentions writings about Brauner’s case and the Surrealist fascination with eyes and sight. So maybe the best thing that can be said is that post hoc prophecying is a lens [sic] on the past, a strategy for making meaning. So is irony, and whether it was prophetic, Brauner’s painting is certainly ironic. Maybe he should have been a Dadaist instead.

While looking for Ivanka’s Christopher Wool next to her Eames lounge chair, I stumbled across this Eames plywood screen that Wool painted in 2002. It was acquired by a Geneva art collector-turned-jewelry designer named Arlene Bonnant for her CAP Collection, which she published a book about in 2005, right before flipping a tranche of it in 2007. Some of her haul might not have ever even made it out of the crate before she flipped it. She held off on selling the screen, though, until 2014.

It’s wild how I can imagine being psyched for an object like at one point, but five minutes of Googling has really soured me on it. What a cursed combination of search terms this turned out to be.

Christmas came early because @nobrashfestivity did some welcome work tidying up this photo of a Christmas tree on a stool in Marcel Duchamp’s Paris studio. The Beinecke still says no date, and I didn’t know it when I posted it in 2021, but in 2008, flickr user leiris202 dated this photo to 1907, which would be six years before the legendary original Bicycle Wheel Duchamp got his sister Suzanne to photograph, so he could backdate his 1915 re-creation.

The wild thing is that there was possibly as much as an entire decade in which Christopher Wool might have known that Ivanka Trump had bought one of his prints, and he might have just thought, “lol weird but whatever.”

And if he just stayed silent during the first administration, when Ivanka was in the White House, but the print wasn’t in her instagram feed, he could have just clammed up and let Richard Prince do all the disavowing.

But now, with her tryna be just a pensive bookfluencer in her DWR chair, dropping her reading list, while her civilian husband cuts a side deal with Putin her dad just [gestures to all this], does Wool feel a little different about his screenprinted exploration of the meaning of abstract painting being used as a backdrop for the regime? Or is it just par for the course? [@crampell.bsky.social via @chrisrusak.com]

[one google search later: oh right, we’ve all known since 2016. I guess Wool just decided to walk the Marfa desert and collect barbed wire about it.]

Since October 2023, Max Schumann, the artist and former director of Printed Matter, has been making paintings based on photos and video clips of protests against the US/Israeli genocide in Palestine. Flag Book is a risograph compilation of this series, and is available again at Printed Matter. [s/o visitor]

Flag Book, 2025, ed. 150 by Max Schumann, $30 [printedmatter.org]

Previously, related, June 2023: Max Schumann Benefit Bash Prints for Printed Matter

Wolfgang Tillmans is selling the remaining posters from his Pompidou exhibition to benefit Between Bridges, his foundation in Berlin that promotes democracy, intercultural dialogue, art, and LGBTQIA+ rights.

I saw it on insta where, Tillmans reports, he can’t mention the name of his foundation because the platform will throttle his post because it reads as advertising, which they want him to pay for.

The posters ship from Europe, which is a phrase that a year ago would have been so normal you wouldn’t even notice it, and now, as I type this, I don’t even know if it’s possible or tariff-throttled.

So I’m gonna buy a poster from an artist I like which I saw on the internet, to support democracy and queer rights, because that is now a revolutionary provocation, apparently. Maybe I should have gotten the Frank Ocean one.

Original exhibition poster: Nothing could have prepared us / Everything could have prepared us (Version 2) €25 [wolfgangtillmans.bandcamp.com/merch via ig]

I don’t even watch TV, and yet knew a couple of weeks ago that Heated Rivalry had broken containment. But I did not expect to ever find reason for it to end up here. And yet. The picture above is from the fourth episode of the six-part series, a sex-forward, gay hockey romance produced by a Canadian streaming service I’ve never heard of, using some undetermined amount of Canadian public media funding. It’s become explosively popular, and transformed its unknown leads from waiters into stars. But that’s not important now, or at least here.

What matters is that someone on Threads—if the post ever turns up in my instagram recommended grid again, I’ll credit them—posted the scene above, and noticed that the painting in between the two guys on the sofa is an abstracted version of the cover of the book from which Heated Rivalry is adapted:

So one guy in the secret eight-year situationship has a portrait of the two of them in a faceoff, hanging over his sofa—which could mean nothing. Honestly, I don’t know what it means, if it’s an actual plot point or just a production design easter egg. And if it was just a neat cover reference, I’d leave it floating on the internet.

But that painting is also similar in both form and approach to paintings by that most Canadian master of Canadian subjects, Douglas Coupland. In 2010 Coupland showed G72K10, a series of paintings geometrically abstracted from iconic landscapes by the Group of Seven, artists who formed the foundation of Canadian visual cultural identity in the early 20th century. “These are the images that the Canadian government officially used…to inculcate a sense of nationalism,” Coupland explained in 2012, “So when Canadians see my abstract works, they know they know what they’re seeing – they just don’t know why”

Is this hockey player’s painting supposed to be a Douglas Coupland? The character is Russian and living in Boston, so probably not. But does that mean the production designers weren’t referencing Coupland, or at least inspired by Coupland’s work and approach? Even the most seemingly incongruous element, the wedges of gold leaf, echo elements in Coupland’s most recent iceberg paintings, in 2023.

The show takes place over many years, and the scene above is in 2016. Which, for Toronto, was a Peak Douglas Coupland Art Moment. He’d just had two museum shows, and unveiled five public art commissions, including at least three new G7-related abstractions, in bank lobbies and plazas all over town.

Now popping geometric abstraction is not just Coupland’s; it’s a language employed by artists as varied as Odili Donald Odita and Dyani White Hawk. But the Canadian force is strong with this one. And Coupland’s low-key intense Canadian-ness seems to resonate with a show that itself has an exceptionally Canadian aura. It’d almost be weird if Coupland wasn’t a reference.

Previously, related, 2011: What I looked at: Douglas Coupland Roots Paintings

It was nice to start seeing emails from Patrick Parrish in my inbox again, but it was not until he posted his speedrun of the recent design auctions in NYC that I realized how much I’d missed his design blog, MONDOBLOGO, in my online life.

Here is Parrish’s photo of Marcel Breuer’s lights reflected across a Ron Arad chair, one of two that didn’t sell at Sotheby’s. He also has photos of a private dinner being set up in the gallery, which used to be the Whitney Museum of American Art, then the Met, then the Frick.

Listening to Luc Tuymans’ interview with Ben Luke on A Brush With… in the car yesterday, I was fascinated by his regular use of a cinematic or almost narrative framework for making his shows. Which sounds distinct from making paintings for a show, although there are apparently paintings that function a specific way in a show, as a start, or a coda. But there is also a crucial structure or sequence, a context that is somehow foundational to a show and the work in it, yet which is unarticulated, or seemingly completely unacknowledged.

And what struck me was that after the show is done, and the works are sold and scattered, this vital structure disappears forever. The paintings are set adrift, left on their own.

Working toward a show and planning a show is not unusual; it even makes a lot of sense. Considering how works in a show will be situated and seen in space and time is also extremely normal. But there was something oddly specific about Tuymans’ discussion of his narrative approach that set it apart; it stuck, but we all moved on.

Then toward the end of the conversation, Tuymans talked about preparing for a show, and then a dealer came and picked some works to take to an art fair, and in the process, wrecked the whole show.

[I’m paraphrasing here, partly because the transcript is not readily available, but mostly because Tuymans also made a throwaway comment about not being “a primadonna, and I always meet my deadlines,” and I am past a deadline on a piece I’ve been stuck on, and typing just to type is a way to break the jam, but also, I’m hoping feeling called out by someone who’s always sounded arrogant to me, and who, frankly, I did kind of imagine as a primadonna, will also get me finished on this damn thing.]

Anyway, Tuymans then said he switched to making art fair work, paintings which exist on their own, conceived as orphans, and void of whatever the narrative structure or context of a show might give them. He went on to say they weren’t exactly lesser works, but…a different priority. [This feels important to get right, and I’ll come back and add the actual quote after a relisten. UPDATE: OK, here.]

Ben Luke: “When you make a work for an art fair, does it differ at all in terms of… do you approach it differently from the subject matter point of view?”

Luc Tuymans: “Yes, because it’s a singular work, or singular works, that are somehow related to what I’m thinking at that moment what could be relevant or not, but it has a different stance. I mean, it doesn’t have the same priority, let’s put it that way, as a show.”

But there is a whole unspoken category of Luc Tuymans Art Fair Paintings, and maybe looking at them alongside/in contrast to his real paintings will be a productive exercise as curators construct narratives of their own.

My incredibly chic landlady at business school used to compare something great to a nickel rocket. One time I asked her where that phrase came from, and she had no idea.

That has nothing to do with anything, really, except Ry Rocklen somehow nickel-plated a whole-ass phonebook, and it looks incredible.

It was kind of overshadowed by the massive trophy altar Rocklen showed it with at Untitled in 2011, but on its own, this feels like the more enduringly interesting object.

Rocklen also nickel- and copper-plated a set of sheets, and then shoes and stuff, all perhaps prelude to Charles Ray making a shiny metal version of him.

“Are you unfurling the—?”

“The limited-edition knit blanket rendition of the cover of issue no. 56 (Spring 1973), featuring Meditation on the Theorem of Pythagoras by Mel Bochner (1940-2025) that’s supposed to start shipping December 15th, but isn’t guaranteed for holiday delivery? Yeah. Yeah I am.”

Issue No. 56 Blanket, Mel Bochner (Limited Edition), $199 [theparisreview.org]