| CARVIEW |

(Images © Gianmarco De Chiara)

More about Gianmarco De Chiara’s work here

]]>

Interviewed by Marinos Tsagkarakis

Edited by Chiara Costantino

Yoav, how did you come to photography?

I have two distinct first memories of coming into photography. When I was really little, 5 or 6 years old, my parents had let me take some photographs and I remember being told that I constantly cropped the heads of the people I shot by accident, and that became a huge concern for me as a child. The second memory, which continues to play a big role in my life, is of me at the age of 8 staging a picture that I’ve asked my father to take. There was a stream of water crossing a picnic area and I wanted my father to photograph me jumping over and across the water. The picture I had in mind was kind of heroic, and I was obviously aware already at the time to the perspective of photography on reality. I’ve waited anxiously for the film to return from the photo shop just to discover a harsh disappointment when the picture I was jumping over the water was nothing like what I have imagined. I was small, shot from above and the stream of water seemed even smaller compared to its surroundings. Ever since I became obsessed with photography. I blamed as a child the cheap point and shoot camera that my family had for the disappointing image and every time I was walking by a camera store I would stand in front of the window display and examine the large professional cameras with their lenses fantasizing what magical photographs I would have captured with them. Even though my entire childhood was based on film cameras, the first camera I owned was a digital one, which I started using during junior high than high school, through my army service and into my BA in photography. I got into photography with the misconception that the camera is responsible for making wonderful photographs, like the ones I’ve always imagined, and slowly learned that it is the photographic perspective through which we adapt to see the world that is responsible for the magic in photography. Today I use Large Format film cameras, which are the simplest cameras. They simply reflect your perspective of reality through the photographed image.

Have you made any studies on photography?

During my B.A in photography I volunteered in the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo in order to enter the restricted areas behind the zoo cages and displays. It was my first body of work where I was taking a Large Format camera outside of the studio. It took me hours to photograph each location. I was sitting on the camera’s large case trying to see the flipped image on the ground glass (an image is naturally upside down when appearing on a ground glass, just like our vision before the brain flips it back) and figure out how to mediate the spaces that not many eyes will see behind the scenes of the Zoo. My more recent work, which I started during my Masters Degree in photography, focuses on the relation of our interpretation and expectations of reality when photography blends seamlessly with our vision of reality.

Tell me more about your photographic work. What are the themes that you focus?

I focus on places with restricted access wither it is because they are restricted and inaccessible to me or rather to many others as well , places and spaces that had been seen in photographs prior to our encounter with them in reality or even places that we will never encounter ourselves and we will know them forever through photographs. My photographic work concerns about the influence photography has on our perception of reality, even places that we never been to are part of our reality if can see them in photographs. As part of my process I build scale models of certain places that I don’t have access to so I can refer to their images as the expectations of the place and the perception of places we either cannot reach or see in photographs before we see them with our own eyes.

You have joined army for 3 years. Has this experience affected your relationship with photography?

The army service was the most surreal period of my life. Nothing really made sense, and the places I had access to during the army became inaccessible after my service, and therefore seem almost fictional or nonexistent. I couldn’t always carry a camera with me during my army service, and an old cellular phone captured the few images I did take with a camera (one of the earliest camera phones). The army service has seeded the urge to regain access to my “photographic memories” – which seem photographic in potential but have never been fulfilled and were not photographed. Eventually miniatures became an instrument through which I revisit my ‘unphotographed’ memories, through building and photographing scale models I can have access to the lost photographic opportunities I have in mind, and share them with the world. After all that is what we do in photography, sharing what our eyes had seen or what we think we remember in my case.

Your images and your projects have vivid elements from American photography. What are your influences?

I have in mind the great nomadic American photographers like Joel Sternfeld, Stephen Shore and Mitch Epstein, who set out for photographic journeys to discover their own homeland. Yet I often feel that they were also seeking for an America as it was portrayed vividly in the work of Edward Hopper and artists like him. Newer works by Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson also comes into mind where the relation to American cinema and the influence of Edward Hopper blend together. These people, these wonderful artists have set a photographic idea of America along with its cinematic history that through which I saw America before moving to New York. My work if so is somewhat in response to the American idiom that I have inherited from the mediated American culture.

What is your project “A form of view” about?

What is your project “A form of view” about?

A Form of View refers to the accumulation of images that form a certain perception of different aspects in our world. Certain elements accumulate to a certain mass that they form a visual vocabulary, which we use to assign a certain cultural narrative to the places, and the landscape that we see. Israel and America are two natural landscapes for me to explore under this body of work because Israel where I grew up in is an Americanized culture and America is the ideal we are looking up to and the place I always dreamt going to. The idea of Israel and the idea of America (USA) is being formed by certain images with certain context. Some images are iconic and play an important role in the historic perception of a place while some other accumulate in many version of the same and form a cultural identifiers that together give us a certain visual idea of what’s Israeli and what’s American. We are being raised and being taught about our world through images the form of the landscape appears under certain context in images. A Form of View therefore has a double meaning – one aims at the actual form of the view – the panoramic view of a landscape while the other meaning suggests that our view is being formed by a vocabulary of contextualized images.

What are the similarities and the differences between American and Israeli culture and how do you illustrate them in your images?

I will start with the biggest difference – America is the origin of Americanization while Israel, like many other countries in the world, are only a copy of this culture. So in some sense Israel is a distorted image of America – replicating cultural aspects as they are being mediated across the ocean and through photography, cinema, consumption and music. The similarities are visual and cultural and this is where it gets both complicated and interesting. It is obvious that they will look similar in some sense – almost all forests look the same (to a certain visual extent) and all deserts look alike. Also an Americanized Israel will appear similar where American culture was imported into Israel. Yet although they appear similar certain aspects that will seem visually correct might be telling a story of a functional misunderstanding – like for example any triangular roof top in Israel is functionally ridiculous – the function of a triangular roof is to support the weight of snow and tiling prevent from rain leaking into the house – both rain and snow are scarce in the Middle Eastern Israel and therefore aspiring to have a triangular roof says a lot on the way we base our culture assimilation on what we can see.

Do you think that your work “A form of view” is close to conceptual photography?

This is a tough question. I know that there is a lot of conceptual thinking going into this body of work, yet I would say that conceptual photography is seeking for something a little bit different. I love conceptual photography yet I cannot give in fully to the restrictions involved when it comes to a conceptual work process – or maybe I never truly understood what is conceptual photography and I was producing conceptual work all along. I think that the biggest thing that differs me from a conceptual artist is the childish background to everything I make.

Tell me who is your favorite American and your favorite Israeli photographer.

My American mentor is the amazing, one and only, David Levinthal. My Favorite Israeli photographer, and my friend, is Shai Kremer, beyond doubt!

(Images © Yoav Friedländer)

More about Yoav Friedländer’s work

Marinos Tsagkarakis was born (1984) and raised in the island of Crete, in SouthernGreece. He studied contemporary photography at STEREOSIS Photography School, in Thessaloniki, Greece. He is a member of the collective “Depression Era” that inhabits the urban and social landscapes of the economic crisis in his home country. His work has been featured in numerous exhibitions and international festivals, including Mois De La Photo in Paris, European Month of Photography and Fotoistanbul. Moreover, he has exhibited his photographs in important art spaces such as Benaki Museum (Athens), Museo de Bogotá (Colombia) and several galleries in Canada, USA and Europe.

]]>

Her works have been published in Italian and foreign magazines.

Interviewed by Chiara Costantino

Hi Tiziana, how did you come to photography?

Since I was a child I’ve always loved art in all its forms, from painting to sculpture and i just needed to find my ideal means of expression: I found it 10 years ago when I received my first camera, I immediately understood that it would become my best friend for a long time, becoming soon an overwhelming passion.

Are there photographers and other artists who influenced you?

Photographically I’m influenced by the work of Robert Adams, William Eggleston, Thomas Struth, Joel Meyerowitz, Stephen Shore, Walker Evans and Italian photographers like Gabriele Basilico, Ghirri and Guido Guidi. Lately I’ve been fascinated by German director Wim Wenders’ photography and by his excellent description of desolate place or urban setting.

On your site you wrote that you have “the anxiety to understand the outside world through the sight”. Please explain how you do it through your photographs.

Photography is for me an exercise of observation and reflection of reality around me, so my photographs are influenced by my perception of reality, from my experience, from my thoughts.

Analog or digital?

Both, but for the most part of my work I use the digital camera, because it gives me more freedom of expression.

You visited many European cities and portrayed them. Which aspects have you focused on?

I am a great lover of urban landscape, my photographic research focuses on the metropolis, seen as a place of dialogue in which I’m in search of the relationship between identity and urban space. For example in my work “Berlin Explorer” I investigated the relationship between history and urban landscape and as the soul of the city and its people are influenced by its architecture.

What countries do you want to visit most and why?

Photography for me means travel, through the images to tell the surrounding reality, dwelling especially on large urban spaces. Photography allows to represent historical memory, everyday life and future. In the coming months I plan two trips; one to Budapest in Hungary, I am very happy, I want to walk along the river Danube and admire the beauty of the architecture of this city, I’m sure the atmosphere will inspire my photographic work, another trip will be in Istanbul in Turkey, a city full of charm and mystery which extends between the continents of Europe and Asia, divided by the charming Bosphorus Strait.

What are your goals for the future?

My goals for the future are experimenting with photography and make new work experiences, travelling to wonderful countries, learning about new cultures and new people and capturing everything with my camera.

Your “Light in the Night” project is about cities at night, when there’s almost no sign of any human presence. Tell us more.

Light in the Night is an open work born in 2013, I photographed at night some European cities such as Bucarest, Krakow, Warsaw, Paris, Praha, Tirana with no traffic, no people, closed shops, metro stations deserted, cities are in a silent solitude and reveal their most intimate side. Streets are animated only by blue Light of the night, neon lights and distant sound and everything is emptied from its daily function. Sometimes there is a human figure and seems to emerge from a dramatic estrangement and lack of communication with the surrounding space. Night experience in the city changes urban space’s perception.

What do you miss the most in your life?

I think I’m very lucky because I have everything I need!!! I live in a city by the sea in southern Italy, where in April is already summer, I am surrounded by my wonderful friends, I have a boyfriend who adores me and with whom I travel a lot and my passion is turning in my work. The only thing I miss is a life experience outside Italy, I would like to live for a while in Berlin or London but I’m working at this

The question you expected me to ask is…

What are your influences beyond photography? Cinema and Literature are the main sources of my inspiration

(Images © Tiziana Bel)

Chiara Costantino (1984) lives in Bologna, Italy. She creates and curates content and social media for Fluster Magazine. She works as a web content editor, social media specialist, translator and web marketer. Chiara loves Sphynx cats, Murakami’s books, vegan cooking and of course photography, especially street and conceptual photography and every work that explores gender and identity. The Internet is her home and you can tweet her at @c84costantino

Chiara Costantino (1984) lives in Bologna, Italy. She creates and curates content and social media for Fluster Magazine. She works as a web content editor, social media specialist, translator and web marketer. Chiara loves Sphynx cats, Murakami’s books, vegan cooking and of course photography, especially street and conceptual photography and every work that explores gender and identity. The Internet is her home and you can tweet her at @c84costantino

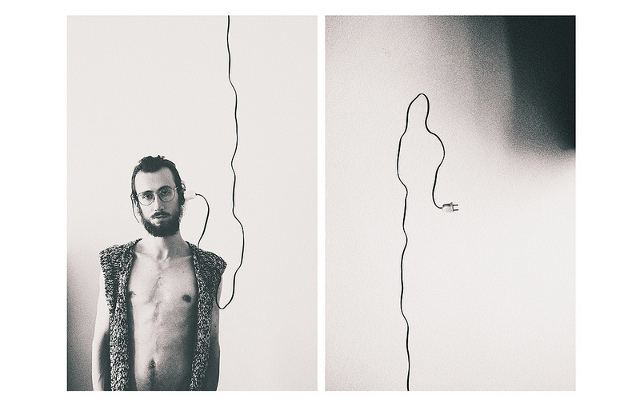

Her main topic are people; it remains crucial in the path of the artist to capture the human individual and grasp its deeper and inner appearance, trying to make it clear through the image.

In 2013 she approached the world of fashion. In 2014 Benedetta was interviewed by Vanity Fair – Style.it in the Emerging Photographers section. Previously she exhibited in group and solo exhibitions in Rome and Milan.

Edited by Chiara Costantino]]>

( Images © Benedetta Ristori) More about Benedetta Ristori's work here

Text and pictures by Milena Fadda

Edited by Chiara Costantino

Sometimes, some places seem to live in an eternal fairy tale. That’s the misreading with the thin line which separates perception from real life. Far from dreamy landscapes and elite tourism, Sardinia is facing the heaviest crisis in its history. Unemployment has reached its maximum rate between 2009 and 2013, with a quarter of the residents living in poverty. Hazardous industrialization and lack of sustainable policies have led to increasing environmental troubles. Through the years, many people have asked themselves which could be the very way to save the day for our resources and our people. We hope not to be so far from the solution. My portfolio focuses on Sardinia caught at the end of its industrial era. During the last 60 years, the second island in Mediterranean Sea, despite its vigorous natural environment, has built up the idea that we all can survive without depending on our territory. Now we ask to ourselves: is economic development worth the price we are paying?

( Images © Milena Fadda)

More about Milena Fadda’s work here

]]>He’s both into analog and digital photography , with a passion for experimental and b&w shots plus electronic music production. His motto is “Street is reality check”.

Currently he’s looking for an editorial/commercial adventure no matter where.

More about Mirko Grifoni’s work here

]]>The Depression Era project is a collective of photographers, artists, researchers, writers, architects, journalists and curators formed in 2011, recording the Greek crisis through images and texts. It was originally inspired by the photographic program of the Farm Security Administration, which was designed to capture the impact of the Great Depression on the American people. Master-minder of the project is the photographer Pavlos Fysakis.

Text by Marinos Tsagkarakis

Edited by Chiara Costantino

The Project started inhabiting the urban and social landscapes of the crisis. It began as a collective experiment, picturing the Greek land, the private lives of outcasts, the collapse of Public systems, the emergence of the Commons and snapshots of the everyday life, aiming to understand and present the social, economic and historical transformation currently taking place in Greece.

The photographers of the Depression Era belong to that new generation of contemporary Greek artists who face the crisis with sensitivity and dynamism, acting with as clear a gaze as possible. One of the greatest advantages of DE’s artists is that they represent a wide range of variety in respect of photographic media, visual languages and aesthetic approaches, embodying personal view and emotion. The target is to get beyond the effects of economic crises attempting to transform all the cumulative energy and disappointment of Greek people into awareness and resistance. They suggest that we should not want “to understand but rather to collect the world”. The “collection” of the crisis is inexhaustible, unlimited and infinite.

The quality of the project is provided by its proposed methods of collective expression, co-existence, shared coordination and widespread dialogue of cultures, besides its ambition to offer a reception of and a critical approach to crisis through the lens of the camera. In the end, what is perhaps most fascinating about this project for the non-Greek viewer is the ways in which the Depression Era understands its images and texts as not Greek, but European. The viewpoints it offers, whether through image or text, or video, give us all an idea of the shape of things to come. They also show ways of overcoming the limiting lines of crisis as a global state of being, a universal, collective turning point.

Last November, Depression Era exhibited a big part of the project at the Benaki Museum in Athens. Moreover, parts of the project have already been showcased at the Bozar Center for Fine Arts in Brussels, at the Mois de la Photo in Paris, the European Month of Photography in Budapest, the PhotoBiennale of the Thessaloniki Museum of Photography and at Fotoistanbul – Beşiktaş International Festival of Photography.

Depression Era Project artists are:

Theofanis Avraam / Petros Babasikas / Georges Charisis / Georges Drivas / Pavlos Fysakis / Marina Gioti / Giorgos Gripeos / Yiannis Hadjiaslanis/ Zoe Hatziyannaki / Harry Kakoulidis / Christos Kapatos / Kostas Kapsianis / Panos Kiamos / Petros Koublis / Nikandre Koukoulioti / Tassos Langis / Maria Louka / Maria Mavropoulou / Dimitris Michalakis / Giorgos Moutafis / Yorgos Prinos / Christina Psarra / Dimitris Rapakousis / Georges Salameh / Spyros Staveris / Olga Stefatou / Angela Svoronou / Vaggelis Tatsis / Yiannis Theodoropoulos / Marinos Tsagkarakis / Dimitris Tsoumplekas / Lukas Vasilikos / Pasqua Vorgia / Chrissoula Voulgari / Eirini Vourloumi.

(Images ©)

More about them and about Depression Era Project here

Marinos Tsagkarakis was born (1984) and raised in the island of Crete, in Southern Greece. He studied contemporary photography at STEREOSIS Photography School, in Thessaloniki, Greece. He is a member of the collective “Depression Era” that inhabits the urban and social landscapes of the economic crisis in his home country. His work has been featured in numerous exhibitions and international festivals, including Mois De La Photo in Paris, European Month of Photography and Fotoistanbul. Moreover, he has exhibited his photographs in important art spaces such as Benaki Museum (Athens), Museo de Bogotá (Colombia) and several galleries in Canada, USA and Europe.

]]>Interviewed by Nassia Kapa

Edited by Chiara Costantino

Hello Mike, tell us a bit about the persona behind the camera. What would be the most important thing you’d like to let people know about you as photographer?

Its essential to separate the art from the artist. Who I am is irrelevant. My work speaks for itself.

What is your relationship with photography? When did it start and what does it mean to you?

Originally, I was interested in film-making but found it to be too collaborative. I want to present a singular vision. Photography allows me that.

Your work is a mixture of documentary and street photography. What sort of stories are interested in telling through your photographs?

I am non political and non conceptual. I present the raw ingredients of a story, and the observer creates the narrative. There is no right or wrong. My intention does not matter to the observer. Once i create the art; the observer owns it.

Tell us about the places you have photographed. Why do they inspire you?

The majority of my work was shot in Istanbul, Bucharest, and Morocco. Everything and everywhere is capable of inspiring me. I revel in being displaced and out of my element; its the main fuel to my creativity. I use the camera to forge an understanding of a new place. It forces me to see things that are hidden and beautiful.

Do you shoot analogue or digital? Why do you often choose the red scale in your photography?

Digital is inherently a compromise. I shoot exclusively analog. I use a lot of expired film, which may account for the “red-scale”.

Many of your photographs evoke a certain atmosphere and a thought provoking light, scenery, despite of complete human absence. Tell us a bit about that.

Many of your photographs evoke a certain atmosphere and a thought provoking light, scenery, despite of complete human absence. Tell us a bit about that.

Atmosphere is always my main focus; with or without humans. I want to provoke something intangible rather than concrete. Instead of stories; i want to convey feelings.

How do you see yourself as photographer in 5 years?

I foresee nothing. The only thing on my mind is what I will create today. 5 years from now it will be the same; only I hope to be rich and famous.

Any projects you are currently working on and would develop in the future?

I have an ongoing project of self-portraits taken in street scenes. The self tends to be obscured and distracted by the more obvious surroundings.

Beside photography, what other source of communicating stories would you use?

I want to be a novelist, but right now my main focus is visual arts.

Give an advice to young fellow photographers out there.

There are no rules. Strive to be the best or else there is no point.

(Images © Mike Lund)

More about Mike Lund’s work here

Nassia Kapa, aka Nassia Katroutsou, is an independent self-taught Greek photographer based in London, UK. Restless in mind and passionate in heart, she only realised her genuine obsession with photography, when her need for self-awareness and repositioning in life was of vital importance. She has participated in local exhibitions in Athens, Greece and her work has been hosted among Greek and international photography related web pages and magazines. Nassia Kapa is an escape exit for Nassia Katroutsou, and her main target is to experience life to it utmost limits, using photography as a vehicle.

]]>

Edited by Chiara Costantino

( Images © Barbaros Cangürgel)

More about Barbaros Cangürgel’s works here

]]>

Text and pictures by María Callizo Monge

Edited by Chiara Costantino

Lineas Alienadas (Alienated Lines) is a work in progress that started in 2010. It describes overpopulation, massive construction and lack of individuality. María Callizo’s work talks about overcrowding and the inability to find ourselves; the huge amount of people living in the same area, people who come and go, people who escape. Thousands of people and buildings, gathered into a mass. There is no space.

Life disappears and is replaced by hundreds of new lives.

Who are you, compared to this immense mass?

How to find out what you are looking for, in such an overcrowded world?

How to find out our individuality?

( Images © María Callizo Monge)

More about María Callizo Monge’s work

]]>