| CARVIEW |

In December 2025, the White House sent a letter to the Smithsonian Institution requesting extensive documentation related to exhibitions, educational materials, internal processes, and collections. The request followed an earlier directive tied to an executive order and was framed as part of federal oversight.

In principle, this kind of oversight is not only appropriate—it is necessary. The President and senior staff have a responsibility to ensure that federally-funded institutions are operating effectively and that public resources are protected from waste, fraud, or abuse. Museums, like any other organizations that receive public funds or tax exemptions, should expect scrutiny and be prepared to demonstrate sound management and professional standards.

What concerns me is not the idea of oversight, but the scale, scope, and apparent purpose of this particular request. From a museum management and governance perspective, much of what is being asked for would require significant staff time to assemble, while providing little information that would actually inform decisions about efficiency, risk, misuse of funds, or as they phrased it, “Americanism.”

As someone who has worked with museum boards, executive directors, and city councils for more than three decades, I see troubling patterns here—patterns I have seen before, much closer to home.

First, I’ll share my open letter to Vince Haley, Director of the Domestic Policy Council, and Russell Vought, Director of the Office of Management and Budget, then I’ll relate this to museums and historic sites.

A Practical Take on the Smithsonian Review

Dear Mr. Haley and Mr. Vought,

The Administration’s interest in oversight and accountability at the Smithsonian makes sense. But as currently framed, this request is likely to consume a lot of time, produce uneven information, and create more confusion than clarity. There is a cleaner, more effective way to do this.

I’m writing as a museum professional who has spent more than thirty years working with boards, executives, and public institutions on governance, operations, and performance. I’ve seen what works—and what doesn’t—when large, complex organizations are reviewed under tight timelines.

The Smithsonian doesn’t operate like a single agency. It operates like a large, decentralized enterprise: 21 museums, the National Zoo, multiple research centers, and collections well over 150 million items. Authority, records, and systems are spread across many units. That structure isn’t a problem—but it does mean the scope of a review matters a lot.

Some parts of the request are straightforward and reasonable. Asking for current exhibition texts, public-facing materials, organizational charts, and formal approval processes is normal oversight and can be done.

Other parts are where things start to break down. Asking for a comprehensive inventory of 150 million items in the collections is like asking a multinational company to quickly produce one master list of every asset—from pencils to tractors—across all divisions and systems. Technically possible, but expensive, disruptive, and unlikely to give you clean or decision-ready information. The same is true for broad requests for internal communications, which tend to pull staff away from core work and generate huge volumes of material with limited payoff.

There’s also a line that’s worth being careful about. Oversight works best when it’s focused on accuracy, standards, and stewardship of resources. When document requests start to look like a way to drive specific interpretive outcomes—such as requiring a certain tone, viewpoint, or Americanism—it blurs the line between oversight and management. From a business perspective, that makes objective review harder, not easier.

Finally, the Smithsonian’s governance model matters. It’s a trust instrumentality with its own established records and disclosure practices, not a typical executive-branch agency (see Smithsonian Directives 501 and 807). Treating it as if it were subject to routine FOIA-style production increases legal and operational risk without improving results.

If this were a private-sector review, the fix would be simple: tighten the scope, phase the work, and focus first on the information that actually supports executive decisions. Start with public-facing materials and formal governance documents. Rely on system descriptions and controls instead of enterprise-wide inventories. Use existing processes rather than creating new ones under deadline pressure.

That approach would get you better information, faster—and with a lot less noise.

Respectfully,

Max van Balgooy

Why This Feels Familiar to Museum Professionals

What troubles me most is how familiar this dynamic feels.

I have seen the same behavior play out in museums when a board president or donor demands excessive information, insists on reviewing operational details beyond their expertise, or pushes staff into time-consuming exercises that have little to do with mission, impact, or sustainability. Often it looks like bullying.

The pattern is predictable:

- Staff time is diverted from mission-critical work.

- Morale suffers.

- Decision-making slows.

- The organization becomes reactive rather than strategic.

These actions are often justified as “oversight” or “accountability.” In reality, they rarely improve performance. More often, they reflect a belief that authority alone confers insight—that because someone can demand information, they therefore should.

Let’s be clear about where responsibility does—and does not—lie in these situations.

Staff are not responsible for holding board members accountable. They typically do not vote, they report to the board, and their job security depends on maintaining that relationship. Expecting staff to “push back” against inappropriate board behavior misunderstands the power dynamic and places them in an impossible position.

The only people who can correct bad behavior are other board members.

When peers stay silent to avoid conflict or quietly resign when things get uncomfortable, the problem does not go away. It deepens. Silence is tacit approval of misbehavior and resignation removes exactly the voices that could restore balance and perspective.

This is where governance truly fails (and where we might also apply the same expectations of Congress).

Boards have a fundamental duty of loyalty to the organization and a responsibility to the public it serves. Allowing one individual—whether a board chair or a wealthy donor—to distract staff from the mission, misuse resources, or impose costly demands with little benefit is a breach of that duty.

When oversight becomes performative, coercive, or disconnected from expertise, it stops serving the public interest. Museum professionals recognize this pattern because we live with its consequences and understand how disruptive it can be.

When governance falters and authority is exercised without sufficient judgment, organizations can lose focus, confidence, and capacity. Recovering from that kind of disruption is rarely quick; it often takes years to rebuild trust, realign around mission, and regain momentum. In some cases, I have seen organizations struggle so deeply that their survival was put at risk. Ultimately, these failures affect not just internal operations, but the public trust itself.

Museums exist to serve the public good, and requires oversight that is informed, proportionate, and grounded in responsibility.

]]>

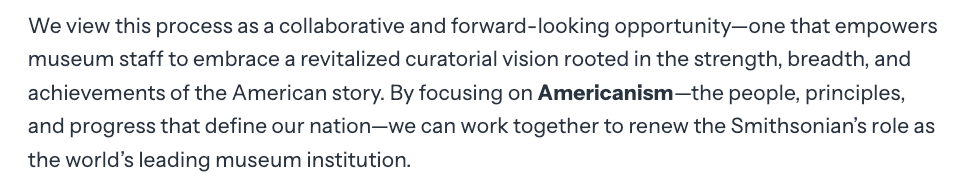

Graduate students recently finishing an introductory course in museum management with me at George Washington University offered useful insights to the field. Their end-of-semester reflections reveal where emerging professionals are gaining traction, where they’re still uncertain, and what this means for museums and nonprofits navigating an increasingly complex landscape.

What’s clicking

A clear shift is underway in how new professionals understand museums. Rather than seeing them as a set of departments or activities, students are beginning to read museums as systems: mission, governance, finances, staffing, and programs working together—or, sometimes, at cross-purposes. Core documents like budgets, Form 990s, strategic plans, and bylaws are no longer viewed as bureaucratic paperwork, but as evidence of priorities, capacity, and risk.

Equally important, many students are learning that management is less about finding the “right” answer and more about making defensible decisions with imperfect information. That realization—often uncomfortable—is a sign of professional formation. They are also becoming more fluent in professional communication: writing memos for decision-makers, structuring findings, and using standards as tools rather than checklists.

Where the strain shows

The productive strain is familiar to anyone who has worked in museums. Students struggled most when ideals collided with constraints—especially around finances, staffing, and governance. They felt the tension between mission-driven aspirations and organizational realities. That’s not a weakness; it’s the work.

More fragile, however, is the step from analysis to action. Many can diagnose issues well, but hesitate when asked to prioritize recommendations, weigh tradeoffs, or state clearly what should happen next given limited resources. Technical confidence—especially in presenting data clearly—also varies, suggesting that some skill gaps are practical rather than conceptual.

Why this matters now

For museums and nonprofits, this snapshot highlights both opportunity and risk. The opportunity lies in a generation of professionals who are learning early to think systemically, read institutions critically, and value evidence over intuition. That’s exactly what organizations need as they confront sustainability challenges, governance pressures, and heightened accountability.

The threat is a familiar one: without intentional mentoring and organizational cultures that support judgment, these emerging skills can stall. If early-career staff are shielded from budgets, planning documents, or board dynamics—or if recommendations are discouraged in favor of task execution—professional growth slows, and institutions lose potential leadership capacity.

Implications for the field

For museum managers and nonprofit leaders, the message is straightforward:

- Invite early-career staff into the real work. Where appropriate, share documents, explain tradeoffs, and talk openly about constraints. Transparency builds competence.

- Model prioritization. Show how you decide what not to do. This is often more instructive than celebrating new initiatives.

- Treat feedback as development, not evaluation. A culture that values revision and judgment over point-scoring mirrors how professional work actually happens.

- Invest in practical fluency. Small supports—templates, examples, shared language around evidence and recommendations—can dramatically improve confidence and effectiveness.

What comes next

For emerging professionals, the next step is practice: turning analysis into action, recommendations into decisions, and discomfort into judgment. For leaders, the task is to recognize that this developmental phase is not a liability but an asset—if it’s supported.

Museums and nonprofits don’t just need passion. They need people who can read systems, navigate constraints, and make thoughtful choices. The encouraging news? That capacity is already taking shape. The challenge now is whether our institutions are ready to meet it.

]]>

Apple Podcasts recently named The Rest is History its Podcast of the Year, and in a December 4 interview on In Conversation from Apple News, hosts Dominic Sandbrook and Tom Holland reflected on why history is resonating so strongly today. Sandbrook argues that despite assumptions, young people are deeply interested in the past—provided it is presented through compelling stories and vivid characters. Academic historians, he suggests, sometimes struggle to reach broad audiences because they avoid narrative. For Sandbrook, stories of the Second World War, Greek myth, the Trojan War, and Rome endure because they are foundational to human identity.

Holland adds that today’s students confront unprecedented content pressures, but unlike earlier generations, they are no longer limited to school as the sole venue for learning. The internet has created a lifelong landscape for historical discovery—“an enormous seam of gold,” as he describes it.

Their recognition is encouraging for museums and historic sites, which have long demonstrated that history becomes meaningful when it connects to human experience. Yet the podcast’s success also presents competitive pressure: if digital storytellers set the bar for engagement, museums cannot rely on authority alone.

Podcasts and digital media compete for attention, but they also model narrative techniques museums can adapt—story arcs, character focus, thematic depth. Museums hold assets podcasters do not: authentic places, objects, and in-person experiences that create emotional resonance and trust. The threat is complacency; the opportunity is reinvention.

Next Steps for Museums and Nonprofits:

- Double down on narrative interpretation that moves beyond names and dates to meaning and human complexity.

- Leverage digital extensions—podcasts, videos, or story-driven social content—to complement onsite experiences.

- Strengthen accuracy and nuance, ensuring that relevance never compromises rigor.

- Use interest in popular history as an entry point for deeper engagement, dialogue, and community connection.

The Rest is History reminds us: audiences are ready for ambitious, meaningful storytelling. Museums must continue to meet that appetite with clarity and courage.

]]>

Over the years, I’ve noticed something consistent in my museum management courses: graduate students are well-prepared to write academic papers, but many struggle when asked to write professional memos—the format that museum directors, CEOs, and board members actually read.

This isn’t a flaw in their abilities; it’s a mismatch between what universities traditionally teach and what museums need. Academic writing is designed to demonstrate thinking. Managerial writing is designed to support decisions.

In the museum field, we write memos all the time—to recommend actions, summarize findings, or prepare leaders for decisions. That’s why many of the assignments in my courses require students to write to a real audience: a museum director, board chair, or CEO. Students practice being clear, concise, and actionable—skills that will serve them throughout their careers.

At recent professional conferences, I’ve also heard colleagues say that emerging professionals often struggle with executive communication. They know their subject matter, but don’t always know how to structure recommendations for decision-makers. Supervisors want to help, but explaining “how to write a memo” can be surprisingly difficult without concrete models.

For years, I’ve used the FranklinCovey Style Guide for Business and Technical Communication as the foundation (available free online). It offers excellent standards and a managerial memo structure that aligns beautifully with museum leadership needs.

Still, many students found it challenging because executive writing feels so different from college writing. So I created a new two-page memo about memos: “Writing Professional Memos in Managerial Format” (available as a free download at the end).

This short guide distills what I’ve learned by reviewing hundreds of student memos in my courses. It breaks down the memo structure step-by-step, highlights common pitfalls (such as burying recommendations on page three), and offers tips for clearer, more confident writing.

If you are:

- an emerging museum professional trying to communicate more effectively, or

- a supervisor or mentor wanting a way to teach your staff what “good” executive writing looks like,

this handout may help.

You’re welcome to use it, adapt it, and share it freely. There’s nothing unique or proprietary about it, and you’re welcome to remove my name and use it with your own staff or students. If it helps strengthen communication in our field, that’s a win.

Clear writing leads to better decisions. Better decisions lead to better museums.

If you try it with your team or students, I’d love to hear how it goes. What other tools would help emerging professionals build confidence in their communication? Let me know in the comments or email me directly. And if you prefer a Word version, I’m happy to provide it via email.

]]>

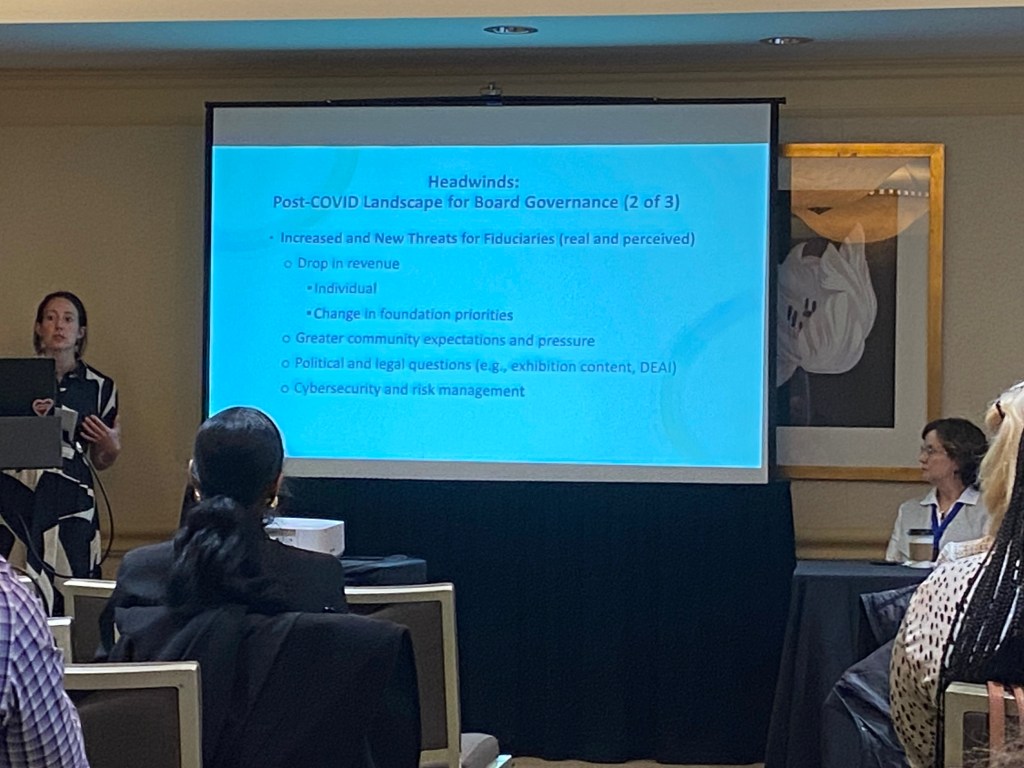

At the recent Mid-Atlantic Association of Museums (MAAM) conference in Pittsburgh, I attended “Headwinds and Tailwinds: A Panel Discussion about the Financial and Operational Impacts on the Museum and Arts Management Field.” One of the panelists, Hayley Haldeman of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, offered particularly insightful observations about board governance in the post-COVID landscape. Her comments confirmed what many of us have observed firsthand—museum boards are facing more challenges and opportunities than ever before.

A Changing Landscape—But Familiar Structures

Despite the upheavals of recent years, Haldeman noted that few organizations have made major changes to their board structures. Most boards remain large, and many governance documents have yet to be updated. The notable exception has been a growing emphasis on board diversity—though progress toward real inclusion varies widely.

At the same time, museums are experiencing significant leadership transitions. Many long-serving executive directors have retired, while others are navigating the aftermath of the “Great Resignation,” which has affected both staff and board leadership. These changes can be destabilizing, but they also open the door for renewal.

New Pressures on Museums and Nonprofit Organizations

Board service today comes with new (and sometimes unexpected) responsibilities. Museums and other nonprofit organizations are grappling with a range of threats, both real and perceived:

- Drops in individual giving and shifts in foundation priorities

- Greater community expectations for accountability and transparency

- Political and legal questions (e.g., DEAI initiatives, exhibition content)

- Cybersecurity and AI-related risks

Meanwhile, board members are harder to recruit and retain. COVID-19 reshaped personal and professional priorities, making time an even scarcer resource. For organizations, that means it’s harder than ever to fill board seats, onboard new members, and keep them engaged—especially when board work happens virtually.

Time for a Governance Audit

Haldeman encouraged organizations to treat this moment as an opportunity for a governance refresh. Start with a fundamental question: What do we need from our Board?

- Time: Are we using board members’ time efficiently and effectively? Remember that their time also equates to staff time.

- Treasure: Are we recruiting someone for their potential donation, or could we cultivate them as a donor without a board seat?

- Talent: What expertise, connections, or community insight do we need most right now?

From there, take a close look at whether your governance structure reflects your current needs. For mid-size to large boards, committees can act as the real workhorses—where expertise and engagement meet. Review which committees are essential and which can be sunset. Consider whether temporary task forces might serve specific projects more effectively than creating standing committees with no clear end.

A useful rule of thumb: the number of board members should roughly equal one-third the size of your staff. For example, an organization with 60 staff members might function best with a 20-member board—large enough for diversity of thought, but small enough to remain nimble and manageable.

The Governance Refresh

A comprehensive governance refresh often begins with a Bylaws review (ideally every three years). This isn’t about overhauling your entire system; it’s about ensuring alignment and removing inconsistencies.

Ask key questions:

- Are the committees listed in your Bylaws still active?

- Do your documents still use terms like trustee when you now say board member?

- Are quorum and term limits still appropriate?

Haldeman emphasized that this process takes time (e.g., 18 months or more) and is best done before embarking on a new strategic plan. Success requires clear communication and transparency between staff and board: sharing reports, clarifying responsibilities, and, most importantly, celebrating milestones along the way.

A Moment for Reflection and Renewal

Post-COVID governance may feel more complex, but it also offers a rare opportunity to reimagine how boards can serve our organizations more effectively. By taking stock of what we truly need from our boards and being willing to make thoughtful structural changes we can create governance systems that are not only more efficient and effective, but also more equitable and adaptive.

As Haldeman reminded us, this is the moment to adjust and prioritize—to make sure our boards are ready for what’s next.

]]>

Move beyond what we tell visitors to what they actually do—and discover how eight types of experiences can deepen learning and meaning.

When we think about interpretation in museums and historic sites, we often focus on what we want to say—the stories, facts, and insights that bring history to life. But what if we focused instead on what visitors do?

That simple shift—from content to experience—changes how we design tours, exhibitions, and programs. It encourages us to move beyond “telling” and toward engaging, offering visitors a range of ways to learn, reflect, and connect.

Recently, I’ve been revisiting an idea from educational research called the Eight Learning Events Model, developed at the University of Liège in Belgium. It identifies eight ways people learn: receiving, imitating, practicing, experimenting, exploring, creating, debating, and reflecting. Although the language in their articles is academic (and a bit European in tone), the concept translates beautifully into the world of museums. With a little adaptation, I’ve reimagined these eight learning events as the “Eight Ways to Engage Visitors.”

A Spectrum of Engagement

At one end of the spectrum, visitors receive information. They listen, read, or watch as museums provide structure and context—through a guided tour, an introductory panel, or a short video.

The next few experiences—observing, practicing, and experimenting—invite more active participation. Visitors watch a demonstration, try out a skill, or test how something works. These steps increase a visitor’s sense of agency. The museum moves from telling to showing to inviting.

Further along the continuum, visitors begin to explore on their own. They follow curiosity, seek patterns, or investigate questions that matter to them. When museums provide open-ended routes or interactive tools, visitors start to direct their own learning.

The most powerful experiences often come at the far end: creating, discussing, and reflecting. Here, visitors synthesize what they’ve learned, share ideas with others, and connect it to their own lives.

These moments—discussion circles, story walls, quiet spaces—are the ones people remember long after they leave. When visitors experiment, discuss, and reflect, they create personal meaning from shared experiences.

Methods and Formats

In my own interpretive planning work, I distinguish between methods and formats:

- Formats are the forms or physical shapes of museum activities—tours, exhibitions, workshops, publications, or webinars.

- Methods, by contrast, are the ways that people teach and learn with each other—such as transmitting, demonstrating, discussing, or practicing. They describe how engagement happens.

A person can share knowledge in a one-to-many method (transmission) through different formats, such as a guided tour or a lecture. Likewise, a single format—say, a guided tour—can include multiple methods: a lecture, a conversation, and a demonstration.

Most museums design for formats because they are visible and tangible; methods, by contrast, are often invisible. Yet method may be the more powerful design tool because it determines how meaning is created. The Eight Ways to Engage Visitors provides a vocabulary for thinking about methods—the range of ways museums and visitors can exchange knowledge, ideas, and skills.

When we combine intentional methods with thoughtfully chosen formats, interpretation becomes both more dynamic and more inclusive.

Two Sides of Every Experience

Each visitor experience also involves an action by the museum. Learning isn’t something that happens to visitors—it’s something museums design for.

- When a museum provides information, the visitor receives.

- When a museum demonstrates, the visitor observes and imitates.

- When a museum encourages discussion, the visitor exchanges ideas.

- When a museum prompts reflection, the visitor connects meaning to their own life.

This back-and-forth—between facilitation and participation—helps us see where interpretation succeeds and where it stalls.

If most of our programs fall into the “receiving” category, visitors may leave informed but not transformed. If we neglect the reflective end of the spectrum, visitors may have fun but not find meaning. The goal isn’t to replace one kind of experience with another, but to weave several together in an intentional manner.

A Tool for Reflection and Design

I’ve started using this framework in workshops with museum managers and graduate students, and the results are eye-opening. When museums map their current programs against the eight visitor experiences, patterns quickly emerge.

- A historic site might rely heavily on receiving (guided tours) and observing (demonstrations), but do little to encourage discussion or reflection.

- A history msueum might excel at experimenting and exploring but overlook opportunities for creating or connecting.

Once these patterns are visible, teams can ask sharper questions:

- Where could we build in opportunities for visitors to try, talk, or reflect?

- How can we balance structured and self-directed learning?

- How might our interpreters shift from delivering content to facilitating engagement?

Even small adjustments can make a big difference—a single open-ended question, a pause for reflection, or a prompt inviting visitors to share their own story can move people toward deeper engagement.

From Learning to Meaning

In the end, the Eight Ways to Engage Visitors isn’t just a checklist of techniques; it’s a mindset. It reminds us that visitors are active participants in meaning-making, not passive recipients of information.

Museums design the spaces where people can observe, wonder, test, create, and connect. By intentionally varying the kinds of experiences we offer, we not only serve different learning styles but also invite more personal, memorable encounters with the past.

Museums don’t simply preserve history or display art—they host experiences that help people understand themselves and the world around them.

If visitors leave not just knowing something new, but feeling inspired to explore, question, or create, then we’ve done our job well.

References

Leclercq, Dieudonné and Marianne Poumay. “The Eight Learning Events Model and Its Principles, Release 2005-1.” Liège, Belgium: LabSET, University of Liège, 2005. https://www.labset.net/media/prod/8LEM.pdf.

Verpoorten, Dominique, Marianne Poumay, and Dieudonné Leclercq. “The Eight Learning Events Model: A Pedagogic Conceptual Tool Supporting Diversification of Learning Methods.” Interactive Learning Environments 15, no. 2 (August 2007): 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820701343694.

]]>

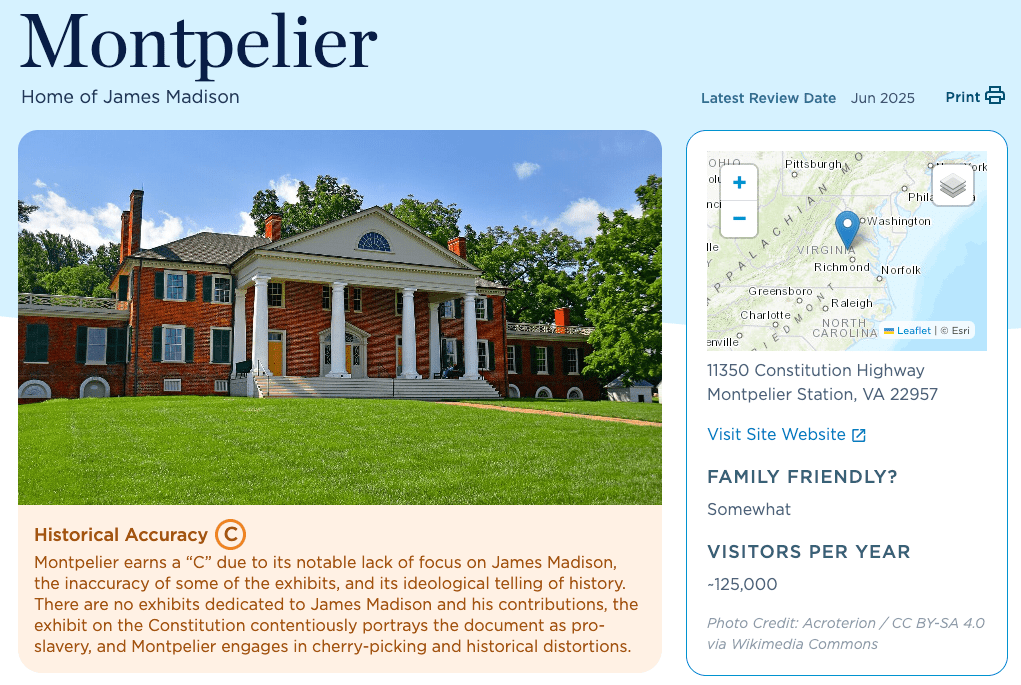

The Heritage Foundation’s new The Heritage Guide to Historic Sites: Rediscovering America’s Heritage promises to help Americans find “accurate” and “unbiased” history at presidential homes and national landmarks. Presented as a travel and education tool for the nation’s 250th anniversary, the site grades historic places from A to C for “accuracy” and “ideological bias.”

At first glance, it looks like a public service. But a closer look reveals that even when Heritage cites “evidence,” its historical reasoning exposes deep methodological and ideological flaws.

The Appearance of Evidence

The Heritage Foundation awards James Madison’s Montpelier in Virginia a C for historical accuracy, claiming the site shows a “notable lack of focus on James Madison” and that:

- Montpelier’s exhibition on the Constitution “gives the impression that slavery was the central animating force behind the Constitution.”

- Exhibit panels “contradict Madison’s own views” and fail to note that the framers avoided the word slavery because, as Madison wrote, they “thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.”

- A display on enslaved presidents omits the fact that Washington freed enslaved people in his will.

- One panel misreports that 11% of New Hampshire’s 1790 population was enslaved (instead of 0.11%), an error first identified in 2022 but apparently not corrected.

- A short film in The Mere Distinction of Colour connects slavery’s legacy to present-day racial issues such as police brutality and Black Lives Matter, which Heritage interprets as political.

- Finally, Heritage objects to Montpelier’s 2018 “rubric” for interpreting slavery, which it portrays as “spreading an ideology” of anti-racism and “restorative justice.”

At face value, these sound like factual concerns. Yet on closer examination, they reveal the Guide’s narrow interpretive lens.

Selective Accuracy and Historical Context

One actual error—the 0.11% statistic—is fair criticism. Museums should correct mistakes promptly. But the rest of Heritage’s objections are interpretive disagreements, not demonstrations of inaccuracy.

The Guide appears to focus on Montpelier’s award-winning exhibition The Mere Distinction of Colour, which interprets the lives of enslaved people on the plantation and examines the contradiction between liberty and slavery in the early republic.

Heritage insists that the Constitution’s clauses on “domestic violence and insurrection” referred only to Shays’ Rebellion, not slave revolts. Yet scholarship on the 1787 Convention shows that delegates often discussed internal uprisings and servile insurrections in the same breath; both threatened the new republic’s stability. Historians debate the extent, not the existence, of that connection.

Heritage also treats Madison’s statement about avoiding the word slavery as evidence of moral rejection rather than political compromise—a reading many historians would consider incomplete. The Founders’ choice of the euphemism “a person legally held to service or labor,” after all, didn’t prevent the Constitution from protecting slavery through the Three-Fifths Clause (Article I, Section 2), the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2), and the twenty-year moratorium on ending the transatlantic slave trade (Article I, Section 9).

Yes, President Washington freed the slaves he owned—after he and his wife had died, when they no longer needed people to work their farms. In addition, his will required that his sick and elderly slaves were to be supported—following Virginia law to prevent indigent slaves from becoming the responsibility of the state. This crucial context is missing from Heritage’s critique.

In short, Heritage presents Madison’s selective quotations as final authority and portrays any broader contextualization—about race, power, or contradiction—as “bias.” That is Heritage’s ideology disguised as neutral precision.

Importantly, the exhibition is only part of the visitor experience. The site offers guided tours of Madison’s home to share Madison’s life and legacy; operates the Center for the Constitution; and educates thousands of teachers, police officers, and civic leaders about constitutional principles every year. In other words, there is in fact a notable focus on James Madison and the Constitution—if the reviewer had taken a better look around. Again, the larger context is missing in the Guide.

It seems that Heritage downgraded Montpelier not because it misrepresents Madison, but because it also interprets the enslaved community. The reviewer seems to have evaluated the exhibitions, not the tours or programs that most visitors experience—and ignored substantial examples of balanced, evidence-based interpretation.

Misunderstanding Museum Practice

Heritage’s complaint about the film linking slavery’s legacy to modern racial issues also betrays a misunderstanding of how museums work. Public historians regularly connect historical themes to present-day questions to help audiences find relevance and continuity—one of the field’s best practices in civic education. As Shakespeare observed, “what’s past is prologue.” The past and present are connected and the job of the historian is to make the links visible.

Similarly, the best practices on interpreting slavery that Heritage dismisses as “ideological” was developed with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and a wide range of scholars, museum professionals, and Montpelier descendants. It has been widely adopted for ethical reasons: it involves people in the interpretation of their own ancestors’ lives. Calling this “spreading ideology” mischaracterizes a professional standard for inclusion and accountability.

The Professional Standard: Transparency and Balance

According to the American Historical Association’s Standards of Professional Conduct, historians must present evidence honestly, cite sources, and recognize complexity. Heritage’s Guide does none of this. It quotes selectively, offers no references, and presumes a single correct interpretation of Madison’s intentions.

Heritage’s grading system punishes exactly the practices that organizations like the American Alliance of Museums, American Association for State and Local History, American Historical Association, and National Council on Public History recommend.

Pedagogical Poverty

From the perspective of L. Dee Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning, Heritage’s approach also misses the mark. The Guide values only “Foundational Knowledge”—names, dates, and quotations—while ignoring other essential dimensions of learning:

- Integration: connecting ideas like liberty and slavery.

- Human Dimension: understanding the experiences of enslaved people and their descendants.

- Caring: motivating civic reflection and moral engagement.

- Learning How to Learn: encouraging visitors to question, compare, and evaluate evidence.

Museums like Montpelier intentionally design experiences that nurture these dimensions. Heritage’s “grading” system penalizes them for doing so.

Good history invites visitors to question, connect, and reflect. Heritage’s approach instead tells them to trust its verdicts and avoid sites that challenge them.

Why This Matters

The Historic Sites Guide arrives as museums prepare for the 250th anniversary of American independence. In today’s polarized climate, Heritage’s letter grades offer an easy shorthand: patriotic sites get A’s; those that interpret race, women, or power get C’s.

Heritage’s entry on Montpelier shows how “accuracy” can be reduced to the selective defense of one historical narrative. The organization’s critique, though sprinkled with facts, ultimately rejects the pluralism, transparency, and civic engagement that define best practices in public history—and the values I support for America as well.

For museum professionals, the lesson is clear: maintain high standards of evidence, acknowledge complexity, and keep history connected to the present.

]]>

When was the last time you opened your board manual?

For many nonprofits, that thick binder (or increasingly, PDF) sits quietly on a shelf until a new member joins or a crisis hits. Yet a well-organized, up-to-date board manual is one of the most valuable governance tools an organization can have. It orients new board members, preserves institutional memory, and keeps everyone—staff and volunteers alike—on the same page about the organization’s purpose, policies, and priorities.

Whether your historic site or museum is just forming its first board or has been operating for a century, a board manual is essential. For a new nonprofit, it lays the foundation for consistent governance and clarity of purpose. For an established organization, it keeps institutional memory strong and ensures that practices evolve alongside the organization’s growth. No matter the stage, the goal is the same—clarity, accountability, and continuity.

Let’s take a more detailed look at what a strong board manual should include and how to make it a living document rather than a forgotten binder.

1. Start with the Essentials

This first section grounds board members in the organization’s structure and identity. It’s the snapshot of who we are.

Include:

- Board of Directors list with terms, positions, and contact information

- Board calendar of meetings, events, and key decision points (e.g., budget approval)

- Organizational chart showing relationships between board, committees, staff, and the public

- Mission, vision, and values statements that are current, concise, and approved by the board

- “Quick Facts” page with founding date, budget size, number of staff, and a brief description of core programs

For new board members, this section offers invaluable context. For long-time members, it’s a reminder of the organization’s evolution and impact.

2. The Legal Backbone: Governing Documents

Your organization’s authority comes from its legal foundation. Every board member should have easy access to these documents:

- Articles of Incorporation

- Bylaws

- IRS Letter of Determination confirming nonprofit status

These aren’t just bureaucratic papers. They define the organization’s purpose, structure, and decision-making rules. Review them annually to ensure they reflect current practices. If your board doesn’t already have a schedule for bylaw review (for example, every three years), add that reminder to your manual.

3. Policies: The Framework for Decision-Making

Policies provide the guardrails that help organizations function fairly, transparently, and consistently. They answer the question, How do we do things here? Below are common policy categories and examples.

Administration

Include practical policies such as Document Retention and Disposition and Employee Handbook. These protect the organization’s integrity.

Board-Related: Governance

This refers to how power is exercised to manage an organization:

- Officers and Board Members Job Descriptions clarify expectations for service.

- Board Operating Policy explains how the board functions (e.g., developing agendas, meeting conduct, closed sessions, voting practices)

- Executive Director Job Description defines responsibilities and relation to board

- Committee Descriptions (Executive, Finance, etc.) describe purpose and reporting

- Conflict of Interest Policy, Whistleblower Policy, and Form 990 Review Procedures demonstrate ethical standards

Well-defined policies help avoid confusion, promote transparency, and protect both the organization and its people. When everyone understands how decisions are made and why they’re more likely to make good ones.

Finance

Financial stewardship is a key board responsibility, yet not every board member is a finance expert. That’s why clarity matters.

Include:

- Gift Acceptance Policy that defines criteria and procedures for accepting gifts

- Descriptions of Restricted and Endowment Funds (e.g., endowment or scholarship funds)

- Guidelines for Unrestricted Contributions and Special Funds (e.g. education, outreach, or museum collections funds)

- Investment Policy ensuring the organization’s investments align with the mission and financial objectives while managing risk

Adding short explanations for named funds such as how the Museum Collections Fund or Scholarship Fund is used helps board members understand donor intent and reinforces accountability.

4. Board Meetings: Keeping Records Accessible

A strong manual includes recent meeting agendas, minutes, and financial statements, along with the current budget, strategic plan, and most recent IRS Form 990. Include proof of board and officers liability insurance here as well.

These documents demonstrate transparency and make it easier for members to prepare for meetings, track decisions, and fulfill their fiduciary duties.

For digital manuals, link to shared folders with up-to-date materials. For printed versions, include a note reminding members where to access the most current files online.

5. About the Organization

Don’t underestimate the power of story. A brief history of your organization connects new members to its roots and reinforces why their service matters. Pair it with a summary of programs, initiatives, and member and public benefits to show how board decisions translate into mission impact.

This section can also include milestone achievements or awards—a subtle reminder that good governance has helped get you there.

6. Glossary of Terms

Every field has its jargon—fiduciary responsibility, Form 990, consent agenda, conflict of interest, restricted funds. A glossary gives members the confidence to engage meaningfully in discussions without feeling lost. It’s a small addition that makes a big difference, particularly for first-time board members or those new to the nonprofit sector.

Keeping Your Manual Alive

A board manual should evolve along with your organization. Here are a few best practices for keeping it current and useful:

- Update annually. Set aside time to review and revise it.

- Make it digital. A shared online folder or password-protected board portal allows instant access to updated materials.

- Review at onboarding. Walk new members through the manual during orientation so they understand how it’s organized and what resources it contains.

- Refer to it regularly. Encourage board chairs and committee leaders to reference relevant sections during meetings.

When the board manual is integrated into daily governance rather than treated as an archive, it strengthens the board’s confidence and cohesion.

Why It Matters

A board manual is an essential part of good management for historic sites and house museums. It ensures continuity when leadership changes, clarifies roles in times of uncertainty, and keeps everyone focused on the mission.

For start-up sites, creating a board manual early builds the habits of good governance and transparency from the beginning. For long-standing historic sites and museums, reviewing and refining your manual is an opportunity to align your current work with best practices and evolving standards. Wherever your organization falls on that spectrum, a living, well-maintained board manual keeps your mission, people, and policies moving forward together.

If you need help to create or update a board manual, Engaging Places can assist you. Contact us to learn more.

]]>

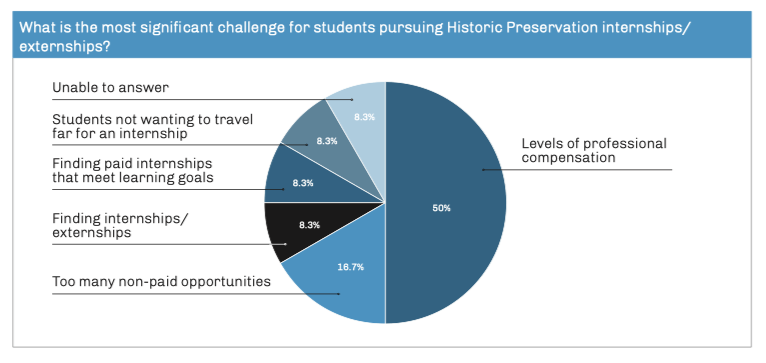

The Jenrette Foundation’s State of American Historic Preservation Education (September 2025) lands like a wake-up call for our field. At more than 25 pages, it’s not just a summary of trends in preservation education—it’s a challenge to rethink what we mean by “historic preservation” altogether. Although the report focuses on universities and training programs, its insights are strikingly relevant for leaders at historic sites and house museums.

At its core, the report argues that historic preservation is due for a rebranding—not a new slogan, but a new mindset. “Preservation isn’t about old buildings,” the authors write, “it’s about shared futures.” That’s a phrase that will resonate with anyone who’s struggled to convince visitors, funders, or policymakers that historic sites matter. For years, preservationists have known that saving a place is just the start; what matters is how that place connects to people, stories, and community life. The Jenrette report gives that idea institutional weight, calling for preservation to be seen as a civic, cultural, and economic force—an engine for workforce development, sustainability, and belonging.

The report’s emphasis on storytelling, collaboration, and interdisciplinary thinking matches the daily realities of site directors who balance history with hospitality, education, and revenue. Its critique of elitism and nostalgia also mirrors the conversations many of us are having about interpretation—whose stories are told, who feels welcome, and how our work contributes to justice and climate resilience.

But the report goes further, urging preservationists to embrace the skills and partnerships that make these ideals sustainable. It recommends closer ties between education and practice—hands-on training, internships, and community-engaged projects that produce professionals who are both thinkers and doers. For historic sites, that’s an invitation to host students, share expertise, and become living classrooms for preservation’s next generation. It also suggests a way to solve one of the field’s persistent challenges: attracting new, diverse talent. If students see historic sites as places of innovation and relevance—not just repositories of the past—they’re more likely to stay in the field.

The report’s economic argument will also sound familiar to site leaders who’ve learned to connect preservation with local vitality. It notes that preservation generates jobs, strengthens small businesses, and fuels cultural tourism—all themes that make our work easier to explain to city councils, chambers of commerce, and donors. Reframing preservation as infrastructure for community resilience could help historic sites position themselves as indispensable civic assets rather than optional cultural luxuries.

The Jenrette report’s most compelling message may be its insistence on humility and openness. Preservation, it argues, must become porous—welcoming new ideas, disciplines, and audiences. That’s a useful reminder for all of us managing historic places: our future depends not on what we’ve saved, but on how we invite others to join the work.

If there are weaknesses in the report it’s an inadequate discussion of methodology and a lack of evidence for their conclusions. It’s unclear who participated in the May 2025 survey or in the June 2025 convening. Was it all academics, as the Foundation’s Historic Preservation Education Advisory Committee is currently composed, or did it include other stakeholders, such as recent graduates of historic preservation programs and the organizations that hire them (e.g., historic sites, house museums, government agencies). The absence of voices from employers, mid-career professionals, and recent graduates weakens claims about “the field” writ large. The report sometimes implies national consensus but it may actually reflect a small subset of university professors.

Despite its weaknesses, the report serves a useful purpose: it articulates the direction preservation education ought to move. It’s a vision document, not a white paper. For leaders at historic sites and house museums, the key is to treat it as an agenda to test, not as settled evidence. The next step should be collaborative research—surveys that include employers, alumni, tradespeople, and community partners—to validate or challenge its claims.

What do you think? Does “historic preservation” generate objections over elitism and nostalgia in your community? How can smaller sites build partnerships with universities or preservation programs to strengthen hands-on learning? What’s one change that could make graduate education more relevant to the realities of your work?

]]>

The timeline is one of the most familiar tools in our interpretive toolkit. It helps us organize facts, identify turning points, and connect events over time. Yet the decision of what to include or exclude shapes the story we tell. Most timelines highlight wars, political milestones, or technological achievements. For many women, those events barely touched their daily lives.

As historian Joan Kelly famously asked, “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” Her answer revealed that what was celebrated as a golden age for men was, in fact, a period of restriction for women. That same question can and should be asked at every historic site: Did women’s lives improve or decline during the turning points we highlight? Or were their defining moments entirely different?

Reimagining the Timeline

What if, instead of centering wars and political leaders, we built timelines around women’s legal rights, economic opportunities, or access to education and institutions?

A productive starting point is the Declaration of Sentiments, drafted at Seneca Falls in 1848. Modeled on the Declaration of Independence, it exposed the inequalities shaping women’s lives—denying them property ownership, wages, custody, and representation. From there, we can trace how laws gradually redefined women’s autonomy.

At historic sites, property rights and control of earnings often provide the most immediate connection to women’s lived experience. These rights determined whether a woman could own her home, keep her wages, or manage inherited land. While suffrage is widely celebrated today, for most women in the nineteenth century, the right to property had a more tangible impact on their daily lives and independence.

The Case of Rebecca Veirs

How might this approach look in practice? It doesn’t take a famous reformer to show the impact of changing laws. Sometimes an ordinary woman’s experience tells us far more about how rights and opportunities evolved over time.

Rebecca Veirs of Rockville, Maryland provides one such example. Born in 1833, she married young and filed for divorce in 1880, seeking custody, alimony, and control of her family farm—rights that would have been impossible a generation earlier. Thanks to changes in Maryland law, she won a legal separation and retained her property. She went on to buy, develop, and sell land in her own name, unheard of just decades before, reshaping her community and her own future.

Her story illustrates how laws and reforms, not national political events, defined her life. A women’s history timeline for Maryland, for instance, might chart the passage of the Married Women’s Property Acts, the right to control wages, or access to divorce—all of which directly shaped women’s lives and agency.

Building Your Own Women’s History Timeline

When creating or revising interpretation, begin by asking:

- What laws governed women’s ownership, earnings, and inheritance in this community?

- When did women first gain (or lose) specific rights here?

- How did race, class, and marital status affect those rights?

Where to look:

- State archives often publish digitized laws and legislative acts.

- The Legal Status of Women in the United States of America series by the U.S. Women’s Bureau summarizes state-by-state changes.

- Legal dictionaries, historical law libraries, and scholarly works can help contextualize reforms.

Why It Matters

By grounding interpretation in women’s legal, social, and economic realities, we move beyond heroic exceptions to uncover the ordinary persistence of women’s lives—their overlooked negotiations, daily labor, and small acts of autonomy.

Timelines built this way do more than mark time. They reveal patterns of progress, resistance, and resilience, helping visitors see that history didn’t just happen to women; women helped make it.

Citations

- Library of Congress, U.S. History Primary Source Timeline, n.d. Online Presentation. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/.

- Joan Kelly, Women, History, and Theory: The Essays of Joan Kelly (University of Chicago Press, 1984), 19-50.

- First Convention Ever Called to Discuss the Civil and Political Rights of Women, Seneca Falls, New York, July 19, 20. July 19, 20, 1848. Online Text. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001107/.

- Lora Liss, Women’s Rights to Property At Divorce In Early Maryland: From Colonial to Modern Times, 1982. Online Text. hdl.handle.net/10822/1051348.