| CARVIEW |

The parameters of the algorithms are a time window and a maximum quota of usage (e.g. requests or bytes) per window. The quota limits the size of a fast burst of requests. The maximum sustained rate is,

rate = quota / window

Leaky bucket and token bucket store the time of the previous request, and a bucket counting the available capacity. The rate determines how quickly capacity becomes available.

It’s easy to see that leaky bucket and token bucket are equivalent, because they simply count in opposite directions:

leaky -= (now - previous) * rate

leaky = clamp(0, leaky, quota)

leaky += cost

previous = now

return leaky < quota ? ALLOW : DENY

tokens += (now - previous) * rate

tokens = clamp(0, tokens, quota)

tokens -= cost

previous = now

return tokens > 0 ? ALLOW : DENY

GCRA tracks a “not-before” time, and allows requests that occur after that point in time. The not-before time is normally in the recent past, and requests increase it towards and possibly (when the client is over its limit) beyond the present time.

time = clamp(now - window, time, now)

time += cost / rate

return time < now ? ALLOW : DENY

It’s not trivially obvious that GCRA is equivalent to the other two. But we can convert the GCRA code into the leaky bucket code with a few transformations, as follows.

We can change from absolute time to relative time by taking now away

from the equations:

bucket = clamp(-window, time, 0)

bucket += cost / rate

return bucket < 0 ? ALLOW : DENY

But that change is incomplete: the stored bucket is relative to the

time of the previous request. To make it relative to the current time,

we need to remember when the previous request occurred, and after

retrieving the bucket we need to shift it to account for the passage

of time:

bucket -= now - previous

bucket = clamp(-window, time, 0)

bucket += cost / rate

previous = now

return bucket < 0 ? ALLOW : DENY

Now we will change units to count tokens instead of seconds. We can do

that by multiplying bucket by the rate, which is measured in

tokens per second. Note that quota = window * rate.

bucket -= (now - previous) * rate

bucket = clamp(-quota, time, 0)

bucket += cost

previous = now

return bucket < 0 ? ALLOW : DENY

Finally, add quota to bucket because positive numbers are nicer,

and we end up with the leaky bucket code.

bucket -= (now - previous) * rate

bucket = clamp(0, time, quota)

bucket += cost

previous = now

return bucket < quota ? ALLOW : DENY

Before writing this down I had a handwavey belief that these algoritms are equivalent – “it’s obvious!” enthusiatic gesturing. The tricky part was to explain the shift from relative to absolute time – why does GCRA use less storage? how does the passage of time become implicit? – so it was worth taking the time to make it as clear as I could.

The standard ITU GCRA variable names are:

-

Λ, the maximum rate, aka quota / window

-

T, the emission interval, 1 / Λ, aka window / quota

-

ta, the arrival time, aka

now -

τ, the jitter tolerance; τ + T == quota

-

TAT, the theoretical arrival time

ITU GCRA compares TAT - τ < ta where my GCRA compares

time < now

My “not-before” time is roughly TAT - τ, but ITU GCRA does the clamp and increment in a different order, so the actual not-before time is TAT - τ - T. This corresponds to the difference between τ and quota.

]]>RateLimit header

fields for HTTP. A RateLimit header in a successful response

can inform a client when it might expect to be throttled, so it can

avoid 429 Too Many Requests errors. Servers can also

include RateLimit headers in a 429 response to make the error more

informative.

The draft is in reasonably good shape. However as written it seems to require (or at least it assumes) that the server uses bad quota-reset rate limit algorithms. Quota-reset algorithms encourage clients into cyclic burst-pause behaviour; the draft has several paragraphs discussing this problem.

However, if we consider that RateLimit headers are supposed to tell

the client what acceptable behaviour looks like, they can be used with

any rate limit algorithm. (And it isn’t too hard to rephrase the draft

so that it is written in terms of client behaviour instead of server

behaviour.)

When a client has more work to do than will fit in a single window’s

quota, linear rate limit algorithms such as GCRA encourage the client

to smooth out its requests nicely. In this article I’ll describe how a

server can use a linear rate limit algorithm with HTTP RateLimit

headers.

spec summary

The draft specifies two headers:

-

RateLimit-Policy:describes input parameters to a rate limit algorithm, which the server chooses based on the request in some unspecified way. The policies are expected to be largely static for a particular client. The parameters are,- the name of the policy

pk, the partition keyq, the quotaw, the windowqu, the quota units

-

RateLimit:describes which policies the server applied to this request, and the output results of the rate limit algorithm. The results are likely to vary per request depending on client behaviour or server load, etc. The results are,- the name of the policy

pk, the partition keyr, the available quotat, the effective window

Both headers can list multiple named policies.

To obey a policy, the client should not make more than q requests

within w seconds. When it receives a response containing a

RateLimit header, the client should not make more than r requests

in the following t seconds.

(The draft calls r and t the “remaining quota” and “reset time”,

which assumes too much about the rate limit algorithm. I prefer to

describe them as the quota and window that are currently in effect.)

policy parameters

The client’s maximum sustained rate is

rate = quota / window

On average the interval between requests at the maximum rate is

interval = 1 / rate

= window / quota

The draft establishes a standard collection of possible quota units, which determine how the cost of a request is counted.

-

qu="requests"cost = 1 -

qu="content-bytes"cost = size of content -

qu="concurrent-requests"(not applicable to this article)

The partition key pk identifies where the server keeps the

per-client rate limit state. Typically a server will have a relatively

small fixed set of rate limit policies, and a large dynamic collection

of rate limit states.

linear rate limit algorithm

This linear rate limit algorithm is a variant of GCRA adapted to

use HTTP RateLimit header terminology.

The per-client rate limit state is just a “not-before” timestamp. Requests are allowed if they occur after that point in time. The not-before timestamp is normally in the recent past, and requests increase it towards and possibly (when the client is over its limit) beyond the present time.

The output results contain r and t values for the RateLimit

header. These must be whole numbers, though internally the algorithm

needs subsecond precision because there can be many requests per

second.

-

Get the client’s rate limit state. New clients are given a default not-before time in the distant past.

time = state[pk] or 0 -

Ensure the not-before time is within the sliding window. The minimum controls the client’s burst size quota; the maximum controls the penalty applied to abusive clients. This

clamp()also protects against wild clock resets.time = clamp(now - window, time, now) -

Spend the nominal time consumed by the request.

time += interval * cost -

The request is allowed if it occurs after the not-before time. The difference between the times determines the available quota and effective window. Round the quota down and the window up to whole numbers, so the client is given an underestimate of its service limit.

if now > time state[pk] = time d = now - time r = floor(d * rate) t = ceil(d) return ALLOW(r, t) -

The request is denied if there is not enough time available. The available quota is zero, and the effective window is the not-before time, rounded up as before.

if time >= now r = 0 t = ceil(time - now) return DENY(r, t)

That’s the core of the algorithm. There are a few refinements to consider, to do with strictness and cleanliness.

Over-limit clients can be treated more or less leniently:

-

The code above allows requests at the permitted rate regardless of how frequently the client makes attempts: denied requests are not counted.

-

Alternatively, the following code denies all requests from a client until its attempts slow down below the permitted rate. The cost is added to the effective window so that enough time is available when the client returns.

if time >= now state[pk] = time d = time - now d += interval * cost r = 0 t = ceil(d) return ALLOW(r, t) -

To apply an extra penalty time-out to clients that make requests within the not-before time, the server can increase the upper bound on the

clamp()into the future.

Finally, it’s a good idea to have a background task that reclaims unnecessary state belonging to idle clients:

for pk, time in state

if time < now - window

delete state[pk]

other rate limiters

The following discussion is mostly about explaining my claims in the introductory paragraphs at the start of this article.

There is a family of linear rate limit algorithms: GCRA behaves the same as a leaky bucket or a token bucket rate limiter (when they are implemented properly – there’s no need for a separate periodic leak / refill task), but GCRA uses less space per client (it doesn’t need an explicit bucket alongside the timestamp) and its code is simpler.

The HTTP RateLimit draft is based on algorithms that reset the quota

and window at a predictable time regardless of client behaviour. (The

draft allows other algorithms, but most of the text makes this

assumption.) After a client makes a burst of requests, it has to wait

until the reset time, then it is allowed to make another burst of

requests.

Another class of algorithm is based on keeping a log of client activity within a sliding window in the recent past. (This is expensive and wasteful!) Sliding-window algorithms allow new requests when old requests age out, so they encourage clients to repeat past behaviour. If a client starts with a burst then it can burst again in each subsequent window.

By contrast, when a linear rate limiter allows a client to make a fast burst of requests, it shrinks the effective window and then keeps the effective window small while the client is busy.

Smaller quotas and windows restrict the burst size, so they require smoother behaviour than larger quotas and windows, even though the ratio quota / window describes the same maximum rate.

Automatically shrinking the effective window reduces the permitted burstiness of subsequent requests. As a result, linear rate limiters smooth out the interval between requests, as well as controlling the number of requests per window.

Other algorithms can make clients behave smoothly too.

A linear rate limiter indirectly assesses a client’s request rate by relating a request counter to the passage of time. By contrast, an exponential rate limiter directly measures a client’s average rate and allows or denies requests by comparing the rate to the limit.

An exponential rate limiter can be used with HTTP RateLimit

headers in a similar manner to a linear rate limiter. That previous

article explains how to calculate the effective window (called

t_next) when a request is denied. When a request is allowed, the

output results for a RateLimit header can be calculated as follows.

(Beware, this snippet uses an awkward mixture of variable names from

this article and the previous article.)

if r_now < quota

state[pk].time = t_now

state[pk].rate = r_now

a = quota - r_now

r = floor(a)

t = ceil(a * window / quota)

return ALLOW(r, t)

The RateLimit header calculation for the exponential rate limiter is

just the reciprocal of the linear rate limiter. It has the same

smoothing effect for the same reasons.

I expect it’s possible to retrofit dynamic window shrinking on to other rate limit algorithms. But (as I wrote yesterday) it’s better to use a simple GCRA linear rate limiter.

PS. The terminology in this article is different from how

I previously described rate limit algorithms: in the past

I used rate = limit / period where the HTTP RateLimit draft uses

quota / window.

But linear (and exponential) rate limiters have a disadvantage: they can be slow to throttle clients whose request rate is above the limit but not super fast. And I just realised that this disadvantage can be unacceptable in some situations, when it’s imperative that no more than some quota of requests is accepted within a window of time.

In this article I’ll explore a way to enforce rate limit quotas more precisely, without undue storage costs, and without encouraging clients to oscillate between bursts and pauses. However I’m not sure it’s a good idea.

linear reaction time

How many requests does a linear rate limiter allow before throttling?

The parameters for a rate limiter are:

q, the permitted quota of requestsw, the accounting time window

So the maximum permitted rate is q/w.

Let’s consider a client whose rate is some multiple a > 1 of the

permitted rate (a for abuse factor)

c = a * q/w

I’ll model the rate limiter as a token bucket which starts off with

q tokens at time 0. The bucket accumulates tokens at the permitted

rate and the client consumes them at its request rate. (It is capped

at q tokens but we can ignore that detail when a > 1.)

b(t) = q + t*q/w - t*a*q/w

The time taken for n requests is

t(n) = n/c = (n*w) / (a*q)

After n requests the bucket contains

b(n) = q + n/a - n

The rate limter throttles the client when the bucket is empty.

b(t) = 0 = q + t * (1 - a) * q/w

0 = 1 - t * (a - 1) / w

t = w / (a - 1)

b(n) = 0 = q + n * (1/a - 1)

0 = q - n * (a - 1) / a

n = q * a / (a - 1)

For example, if the client is running at twice the permitted rate,

a=2, they will be allowed q*2 requests within w seconds before

they are throttled.

That’s a bit slow.

The problem is that the bucket starts with a full quota of tokens, and during the first window of time another quota-full is added. So a linear rate limiter seems to be more generous in its startup phase than its parameters suggest.

fixed window quota resets

This is a fairly common rate limit algorithm that enforces quotas more

precisely than linear rate limiters. It is similar to a token bucket,

but it resets the bucket to the full quota q after each window w.

The disadvantage of periodically resetting the bucket is that careless clients are likely to send a fast burst of requests every window. (A linear rate limiter will tend to smooth out requests from careless clients, though it can’t prevent deliberately abusive burstiness.) And a quota-reset rate limiter uses more space than a linear rate limiter: it needs a separate bucket counter as well as a timestamp.

-

each client has the time when its window started and a bucket of tokens

if c == NULL c = new Client c.bucket = quota c.time = now -

reset the bucket when the window has expired

if c.time + window <= now c.bucket = quota c.time = now -

the request is allowed if the client has a token to spend

if c.bucket >= 1 c.bucket -= 1 return ALLOW else return DENY

hybrid quota-linear algorithm

The idea is to have two operating modes:

-

Low-traffic clients are allowed to make bursts of requests, because that’s good for interactive latency.

-

High-traffic clients are required to smooth out their requests to an even rate.

The algorithm switches to smooth mode when a client consumes its entire quota and the bucket reaches zero, and switches back to bursty mode when the bucket recovers to a full quota.

Bursty mode avoids being too generous by adding at most one quota of tokens to the bucket per window. Smooth mode also avoids being too generous by starting with an empty bucket.

I’ve written this pseudocode in a repetitive style because that makes each paragraph more independent of its context, though it is still somewhat stateful and the order of the clauses matters.

-

the rate limit is derived from the quota and window

rate = quota / window -

a client that returns after a long absence is reinitialized like a new client; in bursty mode the time is the start of a fixed window and the bucket contains a whole number of tokens; we subtract one from the quota to account for the current request

fn reset() c.bucket = quota - 1 c.time = now c.mode = BURSTY return ALLOW -

initialize the state of a new client

if c == NULL c = new Client return reset() -

reset the state when a bursty client’s window has expired

if c.mode == BURSTY and c.time + window <= now return reset() -

when a client consumes its last token, switch modes; in smooth mode the time is updated for every request and the bucket can hold fractional tokens; apply a negative penalty so we don’t allow any over-quota requests before the end of the fixed window; add one to allow the next request at the start of the next window

if c.mode == BURSTY and c.bucket == 1 remaining = c.time + window - now c.bucket = -remaining * rate + 1 c.time = now c.mode = SMOOTH return ALLOW -

smooth mode accumulates tokens proportional to the time since the client’s previous request; update the request time so that tokens accumulate at the same rate whether the request is allowed or denied

if c.mode == SMOOTH c.bucket += (now - c.time) * rate c.time = now -

when the bucket has refilled, switch back to bursty mode

if c.mode == SMOOTH and c.bucket >= quota return reset() -

we have dealt with all the special cases; in either mode the request is allowed if the client has a token to spend

if c.bucket >= 1 c.bucket -= 1 return ALLOW else return DENY

discussion

This hybrid algorithm has a similar effect to running both a quota-reset and a linear rate limiter in parallel, but it uses less space.

The precision of quota enforcement in smooth mode is maybe arguable: It guarantees that the client remains below the limit on average over the whole time it is in smooth mode. But if it slows down for a while (but not long enough to return to bursty mode) it can speed up again and make more requests than its quota within a window.

opinion

I think it’s a mistake to try to treat each time window in strict isolation when assessing a client’s request quota. A linear rate limiter only seems to be unduly generous on startup if you ignore the fact that the client was quiet in the previous window.

As well as being more expensive than necessary (in some cases disgracefully wasteful), algorithms like sliding-window and quota-reset encourage clients into cyclic burst-pause behaviour which is unhealthy for servers. And I’ve seen developers complaining about how annoying it is to use glut / famine rate limiters.

By contrast, rate limiters that measure longer-term average behaviour by keeping state across multiple windows can naturally encourage clients to smooth out their requests.

So on balance I think that instead of using this hybrid quota-linear rate limiter, you should reframe your problem so that you can use a simple linear rate limiter like GCRA.

]]>There are four variants of the algorithm for shuffling an array, arising from two independent choices:

- whether to swap elements in the higher or lower parts of the array

- whether the boundary between the parts moves upwards or downwards

The variants are perfectly symmetrical, but they work in two fundamentally different ways: sampling or permutation.

The most common variant is Richard Durstenfeld’s shuffle algorithm, which moves the boundary downwards and swaps elements in the lower part of the array. Knuth describes it in TAOCP vol. 2 sect. 3.4.2; TAOCP doesn’t discuss the other variants.

(Obeying Stigler’s law, it is often called a “Fisher-Yates” shuffle, but their pre-computer algorithm is arguably different from the modern algorithm.)

the four variants

In the pseudocode below, min and max are the inclusive bounds on

the array to be shuffled; the arguments to rand() are the inclusive

bounds on its return value; and the loop bounds are inclusive too. I

chose this style to make the symmetries more obvious.

In all variants, it’s possible for the indexes this (the boundary

between the parts of the array) and that (chosen at random) to be

the same, in which case the swap is a no-op.

I could have written the loop bounds as min and max instead of

min+1 and max-1 to make the variants look as similar as possible,

but it’s more realistic to omit the loop iterations when this and

that are guaranteed to be equal.

It should be clear that rand() is invoked for spans of each size

between 2 and N (where N = max - min + 1) so the algorithms

produce N! possible permutations as expected.

boundary moves down, pick from lower

shuffle(a, min, max)

for this = max to min+1 step -1

that = rand(min, this)

swap a[this] and a[that]

boundary moves up, pick from higher

shuffle(a, min, max)

for this = min to max-1 step +1

that = rand(this, max)

swap a[this] and a[that]

boundary moves down, pick from higher

shuffle(a, min, max)

for this = max-1 to min step -1

that = rand(this, max)

swap a[this] and a[that]

boundary moves up, pick from lower

shuffle(a, min, max)

for this = min+1 to max step +1

that = rand(min, this)

swap a[this] and a[that]

the two kinds of shuffle

To merge four variants into two kinds, I’ll introduce some names that

allow me to describe them independently of the direction of iteration.

The todo part of the array is ahead of the iterator, i.e. lower if

we are moving the boundary downwards, higher if we are moving it

upwards. The done part of the array is behind the iterator, vice

versa.

Earlier I called this the boundary between the parts, but that was a

deliberate fencepost error which allowed me to gloss over an important

difference. In fact the boundary is next to this, and which side

it’s on depends on the kind of shuffle.

shuffle by sampling

The first two variants above work by sampling.

In this kind of shuffle, the indexes this and that are on the

todo side of the boundary. We pick an element at random from the

todo part of the array, and swap it into position next to the

boundary. Then the boundary is moved so that the picked element is

appended to the done part of the array.

The loop invariant or inductive hypothesis is that the done part of

the array is a random sample of all the elements from the original

array.

shuffle by permutation

The last two variants above work by permutation.

In this kind of shuffle, the indexes this and that are on the

done side of the boundary. First we move the boundary to append an

element from todo to done. Then we pick a random index in done,

and swap the element next to the boundary into that position.

The loop invariant or inductive hypothesis is that the done part of

the array is a random permutation of the elements that were originally

in the same prefix or suffix of the array.

coda

I was inspired to write this by “The Fisher-Yates shuffle is backward” and the examples that were added to Wikipedia’s article on the Fisher-Yates shuffle a few months ago.

The article by “Possibly Wrong” correctly points out that there are two kinds of shuffle, but it misses out one of the four variants. Wikipedia’s examples show all four variants but they are cluttered by conventional array indexing, and it doesn’t explain there are actually two kinds of shuffle.

There’s a classic off-by-one mistake that turns a shuffle into

Sattolo’s algorithm for cyclic permutations. It happens when the

random bounds are too narrow, so that is never equal to this, and

an element can never land in the same place that it started. This

change has the same effect on both kinds of shuffle.

I enjoyed revisiting this old classic and trying to beautify it. I hope you like the results!

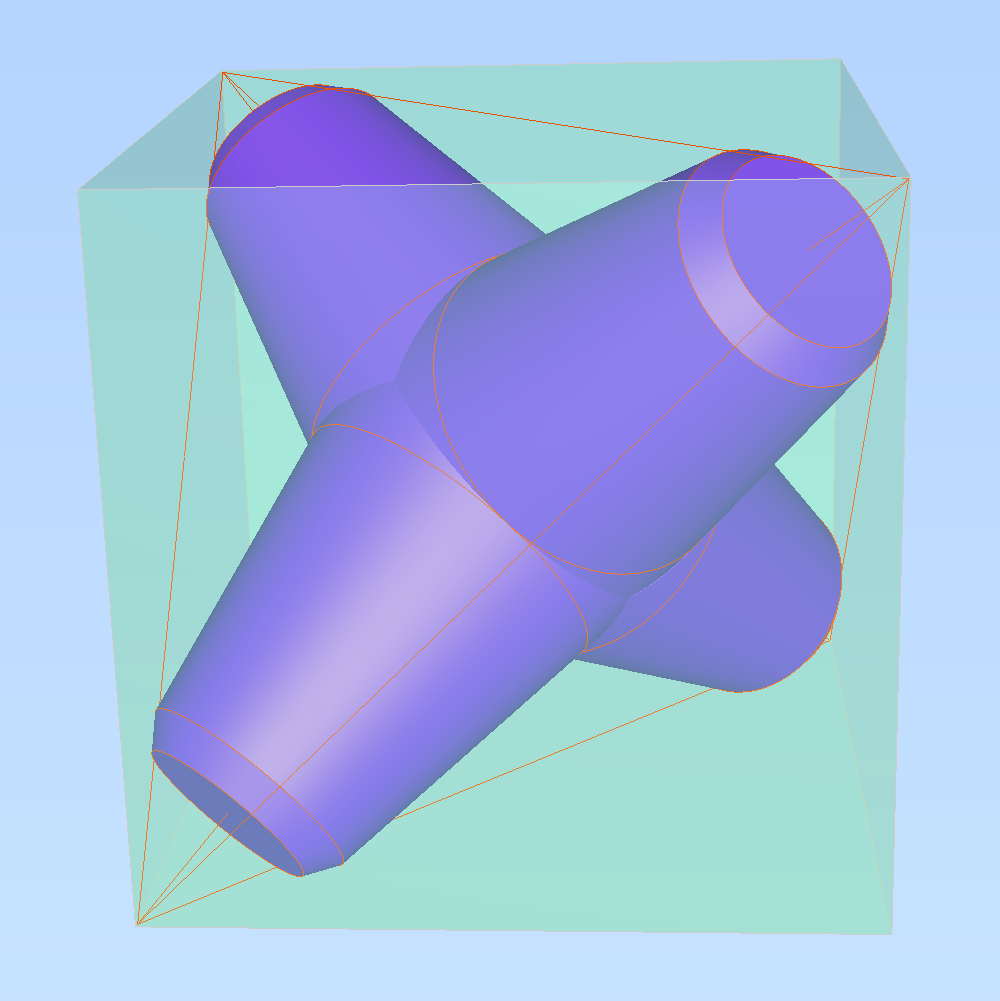

]]>There’s a bit of a craze for making tetrapod-shaped things: recently I’ve seen people making a plush tetrapod and a tetrapod lamp. So I thought it might be fun to model one.

I found a nice way to describe tetrapods that relies on very few arbitrary aesthetic choices.

Click here to play with an animated tetrapod which I made using three.js. (You can see its source code too.)

background and reference material

There is a patent for tetrapods written by the inventors of the tetrapod, Pierre Danel and Paul Anglès d’Auriac. It says,

The half angle a at the apex of the cone corresponding to one leg is between 9° and 14° while the leg length base width ratio b/c for each leg is between 0.85 and 1.15 and is preferably substantially 1/1.

One manufacturer has a diagram suggesting a taper of 10°.

A lot of pictures of tetrapods (one, two, three) have chunky chamfers at the ends of the legs. In some cases it looked to me like the angle of the chamfer matches the angle of the edges of the tetrahedron that the tetrapod is constructed from, which is the same as the angle of the faces of the cube that enclose the tetrahedron.

a surprising experiment

So I thought I would try constructing a tetrapod from the corners of a cube inwards.

My eyeball guesstimate sketch produced a result that’s amazingly neat. It’s the main reason I’m writing this blog post!

Using build123d and CQ-editor, I started with a cube centred on the origin enclosing a tetrahedron, with a common vertex at (100,100,100). I drew a pair of circles near the common vertex, just touching the faces of the cube and edges of the tetrahedron. These circles outlined where I thought the edges of the chamfer might be.

Using a taper angle of 10°, I found another circle centred on the origin that would be the base of the leg. I drew truncated cones to make the leg and chamfer, and replicated them to the three other axes of the tetrahedron.

With a bit of fettling of the sizes of the first two circles, I had a very plausible tetrapod!

To validate this sketch, I found the diameter of the circle around the leg near the centre of the cube where it just touches the x,y,z axes, and the distance from that circle to the end of the leg.

To my surprise, the width and length of the leg both came out very close to 100!

It’s good that they are about the same, because that’s what the inventors of the tetrapod specified. That means my eyeball guesstimate got the proportions about right. What’s amazing is that they match half the side length of the cube that I started with!

recipe for a tetrapod

You can read the source code for a tetrapod drawn using three.js and play with the resulting animation.

preliminaries

-

Pick a size.

The size is the length and diameter of each tetrapod leg, half the height of the tetrapod as it is constructed balancing on two legs, and a few percent less than half the height of the tetrapod when it’s standing on three legs.

-

The tetrapod is constructed inside a cube centred at the origin, with vertices at (± size, ± size, ± size). Inside the cube is a tetrahedron, and the tetrapod’s legs point towards its vertices.

In the picture above, the cube is shaded green, and the tetrahedron is outlined with straight red lines.

-

We will construct the positive leg along its main axis, the vector from the origin to the common vertex (+size, +size, +size).

The three other legs will be cloned from the positive leg.

-

The leg is constructed from truncated cones.

A cone is described by its taper, r / a = tan(θ), where a is the distance from the apex of the cone, and r is the radius of the circular section of the cone at that distance.

Every cone’s axis is the main axis, but their apex varies.

-

A cone is truncated by a circle with radius r and distance d from the origin along the main axis.

(Note that the apex distance a and origin distance d differ when the apex of the cone is not at the origin.)

-

We need two scaffolding cones.

The axis cone has its apex at the orign and its sides just touch the x,y,z axes.

axis_taper = sqrt(2)derivation

z = (0,0,1)

xyz = (1,1,1)

z · xyz = |z| |xyz| cos(θ)

1 = 1 * sqrt(3) * cos(θ)

a / h = cos(θ) = sqrt(1/3)

r² = h² − a² = |z|² − a² = 1 − 1/3

tan(θ) = r / a = sqrt(2/3) / sqrt(1/3) = sqrt(2)

The face cone has its apex at the common vertex. Its sides just touch the faces of the cube along the same lines as the edges of the tetrahedron.

apex_d = size * sqrt(3) face_taper = sqrt(1/2)derivation

xy = (1,1,0)

xyz = (1,1,1)

xy · xyz = |xy| |xyz| cos(θ)

2 = sqrt(2) * sqrt(3) * cos(θ)

a / h = cos(θ) = sqrt(2/3)

r² = h² − a² = |xy|² − a² = 2 − 2*2/3

tan(θ) = r / a = sqrt(2/3) / sqrt(4/3) = sqrt(1/2)

circles

The leg is constructed from four circles: waist, thigh, ankle, sole. In the picture above, you can see the thigh, ankle, and sole circles outlined in red. The waist is hidden inside.

As required by the inventors of the tetrapod, our chosen size is equal to the diameter of the thigh, and to the distance between the thigh and the sole.

The thigh circles just touch each other at the x,y,z axes.

The foot of the tetrapod, between the ankle and the sole, is the chamfered part. It is a section of the face cone.

The ankle circle is chosen so that the taper of the main part of the leg is about 10°. It turns out that a nice round number, r = size / 3, makes the taper 10.41°.

To fill in the core of the tetrapod, between the thigh circles of the four legs, we will extrapolate the leg taper to find the waist circle whose centre is the origin.

Hence,

-

Locate the thigh circle from its radius in the axis cone

thigh_r = size / 2 thigh_d = 0 + thigh_r / axis_taper -

Locate the ankle circle from its radius in the face cone

ankle_r = size / 3 ankle_d = apex_d - ankle_r / face_taper -

The thigh circle and leg length determine the position of the sole circle, from which we get its radius

sole_d = thigh_d + size sole_r = (apex_d - sole_d) * face_taper -

The thigh and ankle give us the taper of the leg

leg_taper = (thigh_r - ankle_r) / (ankle_d - thigh_d) -

Extrapolate back to the origin to find the radius of the waist

waist_d = 0 waist_r = thigh_r + thigh_d * leg_taper

legs

-

Make the positive leg from two truncated cones:

one between the waist and ankle,

one between the ankle and sole.

-

To make another leg, take a copy of the positive leg and rotate it 180° about the x or y or z axis.

Do this for all three axes to get all of the legs.

The legs overlap where their waists spread out around the origin. Conveniently, the legs meet at planes, so we can clip at these planes to make a model where they don’t overlap.

The positive leg meets the other legs at the three planes through the origin with normals:

(1,1,0)

(1,0,1)

(0,1,1)

vital statistics

When standing on three legs with one leg vertical, this tetrapod is

- 2.09 * size tall

- 2.52 * size max wide

- 2.25 * size min wide

The radii of the key circles of the leg are

- 1/2 * size thigh

- 1/3 * size ankle

- 0.27 * size sole

The radii from the vertical axis to the ends of the base legs are

- 1.08 * size to point touching the ground

- 1.37 * size to furthest point

The taper of the leg is 10.4°.

The underside of the tetrapod is surprisingly close to flat.

- 0.17 * size between the ground and the cusp between the legs

- 9.0° angle between skin of legs and ground

The middle of each face of the tetrahedron is close to the core of the tetrapod. That’s partly because of the small 9° angle between the legs and the ground, which is parallel to a face of the tetrahedron. It’s also because the thigh circles protrude a tiny amount through each face, because they are slightly larger than the circles that just touch the x,y,z axes and the faces of the tetrahedron. These inner circles have a radius of sqrt(6/25) * size.

-

The cusp where three legs meet is slightly inside the face, by 0.015 * size.

-

The thigh circles are larger than the inner circles by 0.010 * size.

epilogue

It almost feels like the shape of the tetrapod was discovered rather than designed.

A tetrahedron nested in a cube is a fun framework for a shape. Using half the cube’s side length to determine the length and width of the legs seems like a natural choice. Maybe the choice was based on how close sqrt(6/25) and 1/2 are?

A third of the side length for the taper is a plausible option that turns out quite elegant. Maybe the chamfer at the foot is designed? I like the way it both hints at the cube from which it was constructed, and presumably has good engineering properties such as making the corner less prone to damage and easier to remove from its mould.

One thing I have not yet managed to work out (except by punting the problem to a CAD kernel) is exactly what ellipse is formed where the legs intersect. Investigations continue…

]]>Recently, Chris “cks” Siebenmann has been working on ratelimiting HTTP bots that are hammering his blog. His articles prompted me to write some clarifications, plus a few practical anecdotes about ratelimiting email.

mea culpa

The main reason I wrote the GCRA article was to explain GCRA better without the standard obfuscatory terminology, and to compare GCRA with a non-stupid version of the leaky bucket algorithm. It wasn’t written with my old exponential ratelimiting in mind, so I didn’t match up the vocabulary.

In the exponential ratelimiting article I tried to explain how the different terms correspond to the same ideas, but I botched it by trying to be too abstract. So let’s try again.

parameters

It’s simplest to configure these ratelimiters (leaky bucket, GCRA, exponential) with two parameters:

- limit

- period

The maximum permitted average rate is calculated from these parameters by dividing them:

- rate = limit / period

The period is the time over which client behaviour is averaged, which is also how long it takes for the ratelimiter to forget past behaviour. In my GCRA article I called it the window. Linear ratelimiters (leaky bucket and GCRA) are 100% forgetful after one period; the exponential ratelimiter is 67% forgetful.

The limit does double duty: as well as setting the maximum average rate (measured in requests per period) it sets the maximum size (measured in requests) of a fast burst of requests following a sufficiently long quiet gap.

how bursty

You can increase or decrease the burst limit – while keeping the average rate limit the same – by increasing or decreasing both the limit and the period.

For example, I might set limit = 600 requests per period = 1 hour. If I want to allow the same average rate, but with a smaller burst size, I might set limit = 10 requests per period = 1 minute.

anecdote

When I was looking after email servers, I set ratelimits for departmental mail servers to catch outgoing spam in case of compromised mail accounts or web servers. I sized these limits to a small multiple of the normal traffic so that legitimate mail was not delayed but spam could be stopped fairly quickly.

A typical setting was 200/hour, which is enough for a medium-sized department. (As a rule of thumb, expect people to send about 10 messages per day.)

An hourly limit is effective at catching problems quickly during typical working hours, but it can let out a lot of spam over a weekend.

So I would also set a second backstop limit like 1000/day, based on average daily traffic instead of peak hourly traffic. It’s a lower average rate that doesn’t forget bad behaviour so quickly, both of which help with weekend spam.

variable cost

Requests are not always fixed-cost. For example, you might want to count the request size in bytes when ratelimiting bandwidth.

The exponential algorithm calculates the instantaneous rate as

r_inst = cost / interval

where cost is the size of the request and interval is the time since the previous request.

I’ve edited my GCRA algorithm to make the cost of requests more clear. In GCRA a request uses up some part of the client’s window, a nominal time measured in seconds. To convert a request’s size into time spent:

spend = cost / rate

So the client’s earliest permitted time should be updated like:

time += cost * period / limit

(In constrained implementations the period / limit factor can be precomputed.)

how lenient

When a client has used up its burst limit and is persistently making requests faster than its rate limit, the way the ratelimiter accepts or rejects requests is affected by the way it updates its memory of the client.

For exim’s ratelimit feature I provided two modes called “strict” and “leaky”. There is a third possibility: an intermediate mode which I will call “forgiving”.

-

The “leaky” mode is most lenient. An over-limit client will have occasional requests accepted at the maximum permitted rate. The rest of its requests will be rejected.

When a request is accepted, all of the client’s state is updated; when a request is rejected, the client’s state is left unchanged.

The lenient leaky mode works for both GCRA and exponential ratelimiting.

-

In “forgiving” mode, all of a client’s requests are rejected while it is over the ratelimit. As soon as it slows down below the ratelimit its requests will start being accepted.

When a request is accepted, all of the client’s state is updated; when a request is rejected, the client’s time is updated, but (in the exponential ratelimiter) not its measured rate.

The forgiving mode works for both GCRA and exponential ratelimiting.

-

In “strict” mode, all of a client’s requests are rejected while it is over the ratelimit, and requests continue to be rejected after a client has slowed down depending on how fast it previously was.

When a request is accepted or rejected, both of the client’s time and measured rate are updated.

The strict mode only works for exponential ratelimiting.

I only realised yesterday, from the discussion with cks, how a “forgiving” mode can be useful for the exponential ratelimiter, and how it corresponds to the less-lenient mode of linear leaky bucket and GCRA ratelimiters. (I didn’t describe the less-lenient mode in my GCRA article.)

anecdote

One of the hardest things about ratelimiting email was coming up with a policy that didn’t cause undue strife and unnecessary work.

When other mail servers (like the departmental server in the anecdote above) were sending mail through my relays, it made sense to use “leaky” ratelimiter mode with SMTP 450 temporary rejects. When there was a flood of mail, messages would be delayed and retried automatically.

When their queue size alerts went off, the department admin could take a look and respond as appropriate.

That policy worked fairly well.

However, when the sender was an end-user sending via my MUA message submission servers, they usually were not running software that could gracefully handle an SMTP 450 temporary rejection.

The most difficult cases were the various college and department alumni offices. Many of them would send out annual newsletters, using some dire combination of Microsoft Excel / Word / Outlook mailmerge, operated by someone with limited ability to repair a software failure.

In that situation, SMTP 450 errors broke their mailshots, causing enormous problems for the alumni office and their local IT support. (Not nice to realise I caused such trouble!)

The solution was to configure the ratelimiter in “strict” mode and “freeze” or quarantine over-limit bulk mail from MUAs. The “strict” mode ensured that everything after the initial burst of a spam run was frozen.

When the alert was triggered I inspected a sample of the frozen messages. If they were legitimate newsletters, I could thaw them for delivery and reset the user’s ratelimit. In almost all cases the user would not be disturbed.

If it turned out the user’s account was compromised and used to send spam, then I could get their IT support to help sort it out, and delete the frozen junk from the quarantine.

That policy worked OK: I was the only one who had to deal with my own false positives, and they were tolerably infrequent.

]]>One of the things that jj has not yet tackled is how to do better than git refs / branches / tags. As I underestand it, jj currently has something like Mercurial bookmarks, which are more like raw git ref plumbing than a high-level porcelain feature. In particular, jj lacks signed or annotated tags, and it doesn’t have branch names that always automatically refer to the tip.

This is clearly a temporary state of affairs because jj is still incomplete and under development and these gaps are going to be filled. But the discussions have led me to think about how git’s branches are unsatisfactory, and what could be done to improve them.

branch

One of the huge improvements in git compared to Subversion was git’s support for merges. Subversion proudly advertised its support for lightweight branches, but a branch is not very useful if you can’t merge it: an un-mergeable branch is not a tool you can use to help with work-in-progress development.

The point of this anecdote is to illustrate that rather than trying to make branches better, we should try to make merges better and branches will get better as a consequence.

Let’s consider a few common workflows and how git makes them all unsatisfactory in various ways. Skip to cover letters and previous branch below where I eventually get to the point.

merge

A basic merge workflow is,

- create a feature branch

- hack, hack, review, hack, approve

- merge back to the trunk

The main problem is when it comes to the merge, there may be conflicts due to concurrent work on the trunk.

Git encourages you to resolve conflicts while creating the merge commit, which tends to bypass the normal review process. Git also gives you an ugly useless canned commit message for merges, that hides what you did to resolve the conflicts.

If the feature branch is a linear record of the work then it can be cluttered with commits to address comments from reviewers and to fix mistakes. Some people like an accurate record of the history, but others prefer the repository to contain clean logical changes that will make sense in years to come, keeping the clutter in the code review system.

rebase

A rebase-oriented workflow deals with the problems of the merge workflow but introduces new problems.

Primarily, rebasing is intended to produce a tidy logical commit history. And when a feature branch is rebased onto the trunk before it is merged, a simple fast-forward check makes it trivial to verify that the merge will be clean (whether it uses separate merge commit or directly fast-forwards the trunk).

However, it’s hard to compare the state of the feature branch before and after the rebase. The current and previous tips of the branch (amongst other clutter) are recorded in the reflog of the person who did the rebase, but they can’t share their reflog. A force-push erases the previous branch from the server.

Git forges sometimes make it possible to compare a branch before and after a rebase, but it’s usually very inconvenient, which makes it hard to see if review comments have been addressed. And a reviewer can’t fetch past versions of the branch from the server to review them locally.

You can mitigate these problems by adding commits in --autosquash

format, and delay rebasing until just before merge. However that

reintroduces the problem of merge conflicts: if the autosquash doesn’t

apply cleanly the branch should have another round of review to make

sure the conflicts were resolved OK.

squash

When the trunk consists of a sequence of merge commits, the

--first-parent log is very uninformative.

A common way to make the history of the trunk more informative, and deal with the problems of cluttered feature branches and poor rebase support, is to squash the feature branch into a single commit on the trunk instead of mergeing.

This encourages merge requests to be roughly the size of one commit, which is arguably a good thing. However, it can be uncomfortably confining for larger features, or cause extra busy-work co-ordinating changes across multiple merge requests.

And squashed feature branches have the same merge conflict problem as

rebase --autosquash.

fork

Feature branches can’t always be short-lived. In the past I have maintained local hacks that were used in production but were not (not yet?) suitable to submit upstream.

I have tried keeping a stack of these local patches on a git branch that gets rebased onto each upstream release. With this setup the problem of reviewing successive versions of a merge request becomes the bigger problem of keeping track of how the stack of patches evolved over longer periods of time.

cover letters

Cover letters are common in the email patch workflow that predates git, and they are supported by git format-patch. Github and other forges have a webby version of the cover letter: the message that starts off a pull request or merge request.

In git, cover letters are second-class citizens: they aren’t stored in the repository. But many of the problems I outlined above have neat solutions if cover letters become first-class citizens, with a Jujutsu twist.

-

A first-class cover letter starts off as a prototype for a merge request, and becomes the eventual merge commit.

Instead of unhelpful auto-generated merge commits, you get helpful and informative messages. No extra work is needed since we’re already writing cover letters.

Good merge commit messages make good

--first-parentlogs. -

The cover letter subject line works as a branch name. No more need to invent filename-compatible branch names!

Jujutsu doesn’t make you name branches, giving them random names instead. It shows the subject line of the topmost commit as a reminder of what the branch is for. If there’s an explicit cover letter the subject line will be a better summary of the branch as a whole.

I often find the last commit on a branch is some post-feature cleanup, and that kind of commit has a subject line that is never a good summary of its feature branch.

-

As a prototype for the merge commit, the cover letter can contain the resolution of all the merge conflicts in a way that can be shared and reviewed.

In Jujutsu, where conflicts are first class, the cover letter commit can contain unresolved conflicts: you don’t have to clean them up when creating the merge, you can leave that job until later.

If you can share a prototype of your merge commit, then it becomes possible for your collaborators to review any merge conflicts and how you resolved them.

To distinguish a cover letter from a merge commit object, a cover letter object has a “target” header which is a special kind of parent header. A cover letter also has a normal parent commit header that refers to earlier commits in the feature branch. The target is what will become the first parent of the eventual merge commit.

previous branch

The other ingredient is to add a “previous branch” header, another special kind of parent commit header. The previous branch header refers to an older version of the cover letter and, transitively, an older version of the whole feature branch.

Typically the previous branch header will match the last shared version of the branch, i.e. the commit hash of the server’s copy of the feature branch.

The previous branch header isn’t changed during normal work on the feature branch. As the branch is revised and rebased, the commit hash of the cover letter will change fairly frequently. These changes are recorded in git’s reflog or jj’s oplog, but not in the “previous branch” chain.

You can use the previous branch chain to examine diffs between versions of the feature branch as a whole. If commits have Gerrit-style or jj-style change-IDs then it’s fairly easy to find and compare previous versions of an individual commit.

The previous branch header supports interdiff code review, or allows you to retain past iterations of a patch series.

workflow

Here are some sketchy notes on how these features might work in practice.

One way to use cover letters is jj-style, where it’s convenient to edit commits that aren’t at the tip of a branch, and easy to reshuffle commits so that a branch has a deliberate narrative.

-

When you create a new feature branch, it starts off as an empty cover letter with both target and parent pointing at the same commit.

-

Alternatively, you might start a branch ad hoc, and later cap it with a cover letter.

-

If this is a small change and rebase + fast-forward is allowed, you can edit the “cover letter” to contain the whole change.

-

Otherwise, you can hack on the branch any which way. Shuffle the commits that should be part of the merge request so that they occur before the cover letter, and edit the cover letter to summarize the preceding commits.

-

When you first push the branch, there’s (still) no need to give it a name: the server can see that this is (probably) going to be a new merge request because the top commit has a target branch and its change-ID doesn’t match an existing merge request.

-

Also when you push, your client automatically creates a new instance of your cover letter, adding a “previous branch” header to indicate that the old version was shared. The commits on the branch that were pushed are now immutable; rebases and edits affect the new version of the branch.

-

During review there will typically be multiple iterations of the branch to address feedback. The chain of previous branch headers allows reviewers to see how commits were changed to address feedback, interdiff style.

-

The branch can be merged when the target header matches the current trunk and there are no conflicts left to resolve.

When the time comes to merge the branch, there are several options:

-

For a merge workflow, the cover letter is used to make a new commit on the trunk, changing the target header into the first parent commit, and dropping the previous branch header.

-

Or, if you like to preserve more history, the previous branch chain can be retained.

-

Or you can drop the cover letter and fast foward the branch on to the trunk.

-

Or you can squash the branch on to the trunk, using the cover letter as the commit message.

questions

This is a fairly rough idea: I’m sure that some of the details won’t work in practice without a lot of careful work on compatibility and deployability.

-

Do the new commit headers (“target” and “previous branch”) need to be headers?

-

What are the compatibility issues with adding new headers that refer to other commits?

-

How would a server handle a push of an unnamed branch? How could someone else pull a copy of it?

-

How feasible is it to use cover letter subject lines instead of branch names?

-

The previous branch header is doing a similar job to a remote tracking branch. Is there an opportunity to simplify how we keep a local cache of the server state?

Despite all that, I think something along these lines could make branches / reviews / reworks / merges less awkward. How you merge should me a matter of your project’s preferred style, without interference from technical limitations that force you to trade off one annoyance against another.

There remains a non-technical limitation: I have assumed that contributors are comfortable enough with version control to use a history-editing workflow effectively. I’ve lost all perspective on how hard this is for a newbie to learn; I expect (or hope?) jj makes it much easier than git rebase.

]]>I’ve known for many years that “strongly typed” is a poorly-defined term. Recently I was prompted on Lobsters to explain why it’s hard to understand what someone means when they use the phrase.

I came up with more than five meanings!

how strong?

The various meanings of “strongly typed” are not clearly yes-or-no. Some developers like to argue that these kinds of integrity checks must be completely perfect or else they are entirely worthless. Charitably (it took me a while to think of a polite way to phrase this), that betrays a lack of engineering maturity.

Software engineers, like any engineers, have to create working systems from imperfect materials. To do so, we must understand what guarantees we can rely on, where our mistakes can be caught early, where we need to establish processes to catch mistakes, how we can control the consequences of our mistakes, and how to remediate when somethng breaks because of a mistake that wasn’t caught.

strong how?

So, what are the ways that a programming language can be strongly or weakly typed? In what ways are real programming languages “mid”?

-

Statically typed as opposed to dynamically typed?

Many languages have a mixture of the two, such as run time polymorphism in OO languages (e.g. Java), or gradual type systems for dynamic languages (e.g. TypeScript).

-

Sound static type system?

It’s common for static type systems to be deliberately unsound, such as covariant subtyping in arrays or functions (Java, again). Gradual type systems migh have gaping holes for usability reasons (TypeScript, again).

And some type systems might be unsound due to bugs. (There are a few of these in Rust.)

Unsoundness isn’t a disaster, if a programmer won’t cause it without being aware of the risk.

For example: in Lean you can write “sorry” as a kind of “to do” annotation that deliberately breaks soundness; and Idris 2 has type-in-type so it accepts Girard’s paradox.

-

Type safe at run time?

Most languages have facilities for deliberately bypassing type safety, with an “unsafe” library module or “unsafe” language features, or things that are harder to spot. It can be more or less difficult to break type safety in ways that the programmer or language designer did not intend.

JavaScript and Lua are very safe, treating type safety failures as security vulnerabilities. Java and Rust have controlled unsafety. In C everything is unsafe.

-

Fewer weird implicit coercions?

There isn’t a total order here: for instance, C has implicit bool/int coercions, Rust does not; Rust has implicit deref, C does not.

There’s a huge range in how much coercions are a convenience or a source of bugs. For example, the PHP and JavaScript == operators are made entirely of WAT, but at least you can use === instead.

-

How fancy is the type system?

To what degree can you model properties of your program as types? Is it convenient to parse, not validate? Is the Curry-Howard correspondance something you can put into practice? Or is it only capable of describing the physical layout of data?

There are probably other meanings, e.g. I have seen “strongly typed” used to mean that runtime representations are abstract (you can’t see the underlying bytes); or in the past it sometimes meant a language with a heavy type annotation burden (as a mischaracterization of static type checking).

how to type

So, when you write (with your keyboard) the phrase “strongly typed”, delete it, and come up with a more precise description of what you really mean. The desiderata above are partly overlapping, sometimes partly orthogonal. Some of them you might care about, some of them not.

But please try to communicate where you draw the line and how fuzzy your line is.

]]>My initial sketch was more complicated and greedy for space than necessary, so here’s a simplified revision.

(“p” now stands for prefix.)

layout

A p-fast trie stores a lexicographically ordered set of names.

A name is a sequence of characters from some small-ish character set. For example, DNS names can be represented as a set of about 50 letters, digits, punctuation and escape characters, usually one per byte of name. Names that are arbitrary bit strings can be split into chunks of 6 bits to make a set of 64 characters.

Every unique prefix of every name is added to a hash table.

An entry in the hash table contains:

-

A shared reference to the closest name lexicographically greater than or equal to the prefix.

Multiple hash table entries will refer to the same name. A reference to a name might instead be a reference to a leaf object containing the name.

-

The length of the prefix.

To save space, each prefix is not stored separately, but implied by the combination of the closest name and prefix length.

-

A bitmap with one bit per possible character, corresponding to the next character after this prefix.

For every other prefix that matches this prefix and is one character longer than this prefix, a bit is set in the bitmap corresponding to the last character of the longer prefix.

search

The basic algorithm is a longest-prefix match.

Look up the query string in the hash table. If there’s a match, great, done.

Otherwise proceed by binary chop on the length of the query string.

If the prefix isn’t in the hash table, reduce the prefix length and search again. (If the empty prefix isn’t in the hash table then there are no names to find.)

If the prefix is in the hash table, check the next character of the query string in the bitmap. If its bit is set, increase the prefix length and search again.

Otherwise, this prefix is the answer.

predecessor

Instead of putting leaf objects in a linked list, we can use a more complicated search algorithm to find names lexicographically closest to the query string. It’s tricky because a longest-prefix match can land in the wrong branch of the implicit trie. Here’s an outline of a predecessor search; successor requires more thought.

During the binary chop, when we find a prefix in the hash table, compare the complete query string against the complete name that the hash table entry refers to (the closest name greater than or equal to the common prefix).

If the name is greater than the query string we’re in the wrong branch of the trie, so reduce the length of the prefix and search again.

Otherwise search the set bits in the bitmap for one corresponding to the greatest character less than the query string’s next character; if there is one remember it and the prefix length. This will be the top of the sub-trie containing the predecessor, unless we find a longer match.

If the next character’s bit is set in the bitmap, continue searching with a longer prefix, else stop.

When the binary chop has finished, we need to walk down the predecessor sub-trie to find its greatest leaf. This must be done one character at a time – there’s no shortcut.

thoughts

In my previous note I wondered how the number of search steps in a p-fast trie compares to a qp-trie.

I have some old numbers measuring the average depth of binary, 4-bit, 5-bit, 6-bit and 4-bit, 5-bit, dns qp-trie variants. A DNS-trie varies between 7 and 15 deep on average, depending on the data set. The number of steps for a search matches the depth for exact-match lookups, and is up to twice the depth for predecessor searches.

A p-fast trie is at most 9 hash table probes for DNS names, and unlikely to be more than 7. I didn’t record the average length of names in my benchmark data sets, but I guess they would be 8–32 characters, meaning 3–5 probes. Which is far fewer than a qp-trie, though I suspect a hash table probe takes more time than chasing a qp-trie pointer. (But this kind of guesstimate is notoriously likely to be wrong!)

However, a predecessor search might need 30 probes to walk down the p-fast trie, which I think suggests a linked list of leaf objects is a better option.

]]>The gist is to throw away the tree and interior pointers from a qp-trie. Instead, the p-fast trie is stored using a hash map organized into stratified levels, where each level corresponds to a prefix of the key.

Exact-match lookups are normal O(1) hash map lookups. Predecessor / successor searches use binary chop on the length of the key. Where a qp-trie search is O(k), where k is the length of the key, a p-fast trie search is O(log k).

This smaller O(log k) bound is why I call it a “p-fast trie” by analogy with the x-fast trie, which has O(log log N) query time. (The “p” is for popcount.) I’m not sure if this asymptotic improvement is likely to be effective in practice; see my thoughts towards the end of this note.

layout

A p-fast trie consists of:

-

Leaf objects, each of which has a name.

Each leaf object refers to its successor forming a circular linked list. (The last leaf refers to the first.)

Multiple interior nodes refer to each leaf object.

-

A hash map containing every (strict) prefix of every name in the trie. Each prefix maps to a unique interior node.

Names are treated as bit strings split into chunks of (say) 6 bits, and prefixes are whole numbers of chunks.

-

An interior node contains a (1<<6) == 64 wide bitmap with a bit set for each chunk where prefix+chunk matches a key.

Following the bitmap is a popcount-compressed array of references to the leaf objects that are the closest predecessor of the corresponding prefix+chunk key.

Prefixes are strictly shorter than names so that we can avoid having to represent non-values after the end of a name, and so that it’s OK if one name is a prefix of another.

The size of chunks and bitmaps might change; 6 is a guess that I expect will work OK. For restricted alphabets you can use something like my DNS trie name preparation trick to squash 8-bit chunks into sub-64-wide bitmaps.

In Rust where cross-references are problematic, there might have to be a hash map that owns the leaf objects, so that the p-fast trie can refer to them by name. Or use a pool allocator and refer to leaf objects by numerical index.

search

To search, start by splitting the query string at its end into prefix + final chunk of bits. Look up the prefix in the hash map and check the chunk’s bit in the bitmap. If it’s set, you can return the corresponding leaf object because it’s either an exact match or the nearest predecessor.

If it isn’t found, and you want the predecessor or successor, continue with a binary chop on the length of the query string.

Look up the chopped prefix in the hash map. The next chunk is the chunk of bits in the query string immediately after the prefix.

If the prefix is present and the next chunk’s bit is set, remember the chunk’s leaf pointer, make the prefix longer, and try again.

If the prefix is present and the next chunk’s bit is not set and there’s a lesser bit that is set, return the leaf pointer for the lesser bit. Otherwise make the prefix shorter and try again.

If the prefix isn’t present, make the prefix shorter and try again.

When the binary chop bottoms out, return the longest-matching leaf you remembered.

The leaf’s key and successor bracket the query string.

modify

When inserting a name, all its prefixes must be added to the hash map from longest to shortest. At the point where it finds that the prefix already exists, the insertion routine needs to walk down the (implicit) tree of successor keys, updating pointers that refer to the new leaf’s predecessor so they refer to the new leaf instead.

Similarly, when deleting a name, remove every prefix from longest to shortest from the hash map where they only refer to this leaf. At the point where the prefix has sibling nodes, walk down the (implicit) tree of successor keys, updating pointers that refer to the deleted leaf so they refer to its predecessor instead.

I can’t “just” use a concurrent hash map and expect these algorithms to be thread-safe, because they require multiple changes to the hashmaps. I wonder if the search routine can detect when the hash map is modified underneath it and retry.

thoughts

It isn’t obvious how a p-fast trie might compare to a qp-trie in practice.

A p-fast trie will use a lot more memory than a qp-trie because it requires far more interior nodes. They need to exist so that the random-access binary chop knows whether to shorten or lengthen the prefix.

To avoid wasting space the hash map keys should refer to names in leaf objects, instead of making lots of copies. This is probably tricky to get right.

In a qp-trie the costly part of the lookup is less than O(k) because non-branching interior nodes are omitted. How does that compare to a p-fast trie’s O(log k)?

Exact matches in a p-fast trie are just a hash map lookup. If they are worth optimizing then a qp-trie could also be augmented with a hash map.

Many steps of a qp-trie search are checking short prefixes of the key near the root of the tree, which should be well cached. By contrast, a p-fast trie search will typically skip short prefixes and instead bounce around longer prefixes, which suggests its cache behaviour won’t be so friendly.

A qp-trie predecessor/successor search requires two traversals, one to find the common prefix of the key and another to find the prefix’s predecessor/successor. A p-fast trie requires only one.

]]>comparison style

Some languages such as BCPL, Icon, Python have chained comparison operators, like

if min <= x <= max:

...

In languages without chained comparison, I like to write comparisons as if they were chained, like,

if min <= x && x <= max {

// ...

}

A rule of thumb is to prefer less than (or equal) operators and avoid greater than. In a sequence of comparisons, order values from (expected) least to greatest.

clamp style

The clamp() function ensures a value is between some min and max,

def clamp(min, x, max):

if x < min: return min

if max < x: return max

return x

I like to order its arguments matching the expected order of the

values, following my rule of thumb for comparisons – and the

description of what clamp() does. (I used this flavour of clamp()

in my article about GCRA.) But I seem to be unusual in this

preference, based on a few examples I have seen recently.

clamp is median

Last month, Fabian Giesen pointed out a way to resolve this

difference of opinion: A function that returns the median

of three values is equivalent to a clamp() function that doesn’t

care about the order of its arguments.

This version is written so that it returns NaN if any of its arguments is NaN. (When an argument is NaN, both of its comparisons will be false.)

fn med3(a: f64, b: f64, c: f64) -> f64 {

match (a <= b, b <= c, c <= a) {

(false, false, false) => f64::NAN,

(false, false, true) => b, // a > b > c

(false, true, false) => a, // c > a > b

(false, true, true) => c, // b <= c <= a

(true, false, false) => c, // b > c > a

(true, false, true) => a, // c <= a <= b

(true, true, false) => b, // a <= b <= c

(true, true, true) => b, // a == b == c

}

}

When two of its arguments are constant, med3() should compile to the

same code as a simple clamp(); but med3()’s misuse-resistance

comes at a small cost when the arguments are not known at compile time.

clamp in range

If your language has proper range types, there is a nicer way to make

clamp() resistant to misuse:

fn clamp(x: f64, r: RangeInclusive<f64>) -> f64 {

let (&min,&max) = (r.start(), r.end());

if x < min { return min }

if max < x { return max }

return x;

}

let x = clamp(x, MIN..=MAX);

range style

For a long time I have been fond of the idea of a simple

counting for loop that matches the syntax of chained comparisons, like

for min <= x <= max:

...

By itself this is silly: too cute and too ad-hoc.

I’m also dissatisfied with the range or slice syntax in basically every programming language I’ve seen. I thought it might be nice if the cute comparison and iteration syntaxes were aspects of a more generally useful range syntax, but I couldn’t make it work.

Until recently when I realised I could make use of prefix or mixfix syntax, instead of confining myself to infix.

So now my fantasy pet range syntax looks like

>= min < max // half-open

>= min <= max // inclusive

And you might use it in a pattern match

if x is >= min < max {

// ...

}

Or as an iterator

for x in >= min < max {

// ...

}

Or to take a slice

xs[>= min < max]

style clash?

It’s kind of ironic that these range examples don’t follow the

left-to-right, lesser-to-greater rule of thumb that this post started

off with. (x is not lexically between min and max!)

But that rule of thumb is really intended for languages such as C that don’t have ranges. Careful stylistic conventions can help to avoid mistakes in nontrivial conditional expressions.

It’s much better if language and library features reduce the need for nontrivial conditions and catch mistakes automatically.

]]>the bug

I think it was my friend Richard Kettlewell who told me about a bug he encountered with Let’s Encrypt in its early days in autumn 2015: it was failing to validate mail domains correctly.

the context

At the time I had previously been responsible for Cambridge University’s email anti-spam system for about 10 years, and in 2014 I had been given responsibility for Cambridge University’s DNS. So I knew how Let’s Encrypt should validate mail domains.

Let’s Encrypt was about one year old. Unusually, the code that runs their operations, Boulder, is free software and open to external contributors.

Boulder is written in Golang, and I had not previously written any code in Golang. But its reputation is to be easy to get to grips with.

So, in principle, the bug was straightforward for me to fix. How difficult would it be as a Golang newbie? And what would Let’s Encrypt’s contribution process be like?

the hack

I cloned the Boulder repository and had a look around the code.

As is pretty typical, there are a couple of stages to fixing a bug in an unfamiliar codebase:

-

work out where the problem is

-

try to understand if the obvious fix could be better

In this case, I remember discovering a relatively substantial TODO item that intersected with the bug. I can’t remember the details, but I think there were wider issues with DNS lookups in Boulder. I decided it made sense to fix the immediate problem without getting involved in things that would require discussion with Let’s Encrypt staff.

I faffed around with the code and pushed something that looked like it might work.

A fun thing about this hack is that I never got a working Boulder test setup on my workstation (or even Golang, I think!) – I just relied on the Let’s Encrypt cloud test setup. The feedback time was very slow, but it was tolerable for a simple one-off change.

the fix

My pull request was small, +48-14.

After a couple of rounds of review and within a few days, it was merged and put into production!

A pleasing result.

the upshot

I thought Golang (at least as it was used in the Boulder codebase) was as easy to get to grips with as promised. I did not touch it again until several years later, because there was no need to, but it seemed fine.

I was very impressed by the Let’s Encrypt continuous integration and automated testing setup, and by their low-friction workflow for external contributors. One of my fastest drive-by patches to get into worldwide production.

My fix was always going to be temporary, and all trace of it was overwritten years ago. It’s good when “temporary” turns out to be true!

the point

I was reminded of this story in the pub this evening, and I thought it was worth writing down. It demonstrated to me that Let’s Encrypt really were doing all the good stuff they said they were doing.

So thank you to Let’s Encrypt for providing an exemplary service and for giving me a happy little anecdote.

]]>Recently, a comment from Oliver Hunt and a blog post from

Alisa Sireneva prompted me to wonder if I made an

unwarranted assumption. So I wrote a little benchmark, which you can

find in pcg-dxsm.git.

(Note 2025-06-09: I’ve edited this post substantially after discovering some problems with the results.)

recap

Briefly, there are two basic ways to convert a random integer to a floating point number between 0.0 and 1.0:

-

Use bit fiddling to construct an integer whose format matches a float between 1.0 and 2.0; this is the same span as the result but with a simpler exponent. Bitcast the integer to a float and subtract 1.0 to get the result.

-

Shift the integer down to the same range as the mantissa, convert to float, then multiply by a scaling factor that reduces it to the desired range. This produces one more bit of randomness than the bithacking conversion.

(There are other less basic ways.)

code

The double precision code for the two kinds of conversion is below. (Single precision is very similar so I’ll leave it out.)

It’s mostly as I expect, but there are a couple of ARM instructions that surprised me.

bithack

The bithack function looks like:

double bithack52(uint64_t u) {

u = ((uint64_t)(1023) << 52) | (u >> 12);

return(bitcast(double, u) - 1.0);

}

It translates fairly directly to amd64 like this:

bithack52:

shr rdi, 12

movabs rax, 0x3ff0000000000000

or rax, rdi

movq xmm0, rax

addsd xmm0, qword ptr [rip + .number]

ret

.number:

.quad 0xbff0000000000000

On arm64 the shift-and-or becomes one bfxil instruction (which is a

kind of bitfield move), and the constant -1.0 is encoded more

briefly. Very neat!

bithack52:

mov x8, #0x3ff0000000000000

fmov d0, #-1.00000000

bfxil x8, x0, #12, #52

fmov d1, x8

fadd d0, d1, d0

ret

multiply

The shift-convert-multiply function looks like this:

double multiply53(uint64_t u) {

return ((double)(u >> 11) * 0x1.0p-53);

}

It translates directly to amd64 like this:

multiply53:

shr rdi, 11

cvtsi2sd xmm0, rdi

mulsd xmm0, qword ptr [rip + .number]

ret

.number:

.quad 0x3ca0000000000000

GCC and earlier versions of Clang produce the following arm64 code, which is similar though it requires more faff to get the constant into the right register.

multiply53:

lsr x8, x0, #11

mov x9, #0x3ca0000000000000

ucvtf d0, x8

fmov d1, x9

fmul d0, d0, d1

ret

Recent versions of Clang produce this astonishingly brief two instruction translation: apparently you can convert fixed-point to floating point in one instruction, which gives us the power of two scale factor for free!

multiply53:

lsr x8, x0, #11

ucvtf d0, x8, #53

ret

benchmark

My benchmark has 2 x 2 x 2 tests:

-

bithacking vs multiplying

-

32 bit vs 64 bit

-

sequential integers vs random integers

I ran the benchmark on my Apple M1 Pro and my AMD Ryzen 7950X.

These functions are very small and work entirely in registers so it has been tricky to measure them properly.

To prevent the compiler from inlining and optimizing the benchmark loop to nothing, the functions are compiled in a separate translation unit from the test harness. This is not enough to get plausible measurements because the CPU overlaps successive iterations of the loop, so we also use fence instructions.

On arm64, a single ISB (instruction stream barrier) in the loop is enough to get reasonable measurements.

I have not found an equivalent of ISB on amd64, so I’m using MFENCE. It isn’t effective unless I pass the argument and return values via pointers (because it’s a memory fence) and place MFENCE instructions just before reading the argument and just after writing the result.

results

In the table below, the leftmost column is the number of random bits; “old” is arm64 with older clang, “arm” is newer clang, “amd” is gcc.

The first line is a baseline do-nothing function, showing the overheads of the benchmark loop, function call, load argument, store return, and fences.

The upper half measures sequential numbers, the bottom half is random numbers. The times are nanoseconds per operation.

old arm amd

00 21.44 21.41 21.42

23 24.28 24.31 22.19

24 25.24 24.31 22.94

52 24.31 24.28 21.98

53 25.32 24.35 22.25

23 25.59 25.56 22.86

24 26.55 25.55 23.03