| CARVIEW |

Decades ago when I was in high school, I came across a Samuel Johnson quote: “Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it.”

Decades ago when I was in high school, I came across a Samuel Johnson quote: “Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it.”

It struck a chord with me. That prompted me to read James Boswell’s “Life of Samuel Johnson.”

An interesting bit of trivia. The credit for the first major dictionary of the English language goes to Samuel Johnson, also known as the great lexicographer. His “A Dictionary of the English Language” published in 1755 became the dominant English dictionary for over a century and is considered the first truly authoritative, comprehensive English dictionary.

Today I was reminded of that book during a conversation with a friend. The context was what Trump was doing. I quoted Johnson. “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” Johnson’s view was that pretended patriotism is often used as a cover for self-interest and deceit. He was critical of people who claimed to be patriots while acting in ways that undermined true national interest.

Given our time limitations, it is impossible for us to read more than an infinitesimally small portion of the vast collection of great literature. Fortunately, we have AI agents. They can summarize and surface the best bits. Expert users of AI agents learn where to find information on any subject of interest.

I gave Copilot a simple prompt: “Provide me detailed summary of The Life of Samuel Johnson.” Within seconds, I got a response. Here is an edited version. Begin quote.

A Detailed Summary of Boswell’s Life of Johnson

A detailed summary of The Life of Samuel Johnson is a bit like summarizing a cathedral — it’s not just the structure but the atmosphere that matters — but here’s a full, coherent account of what Boswell actually built and why it remains singular.

Published in 1791, The Life of Samuel Johnson is James Boswell’s monumental biography of his friend, the lexicographer, critic, poet, conversationalist, and moralist Samuel Johnson (1709–1784). It is widely regarded as the greatest biography in the English language — not because of its chronology, but because of its vividness. Boswell turns Johnson into a living presence.

The book blends eyewitness reporting, diary entries, letters, travel anecdotes, verbatim conversations, and Boswell’s own commentary. The result is less a “life” in the conventional sense and more a portrait of a mind in motion.

Boswell recounts Johnson’s difficult childhood: chronic illness, poverty, depression, and a fierce intellectual appetite.

Johnson’s brief time at Oxford is marked by brilliance but cut short by lack of funds. He drifts into school mastering, then into hack writing in Birmingham and later London.

Boswell emphasizes Johnson’s early struggles with melancholy, his lifelong fear of insanity, and his moral seriousness, already fully formed.

London and the Making of a Man of Letters

Johnson arrives in London nearly penniless and begins the long grind of literary labor: writing for magazines, translating, producing political pamphlets, and eventually composing The Dictionary of the English Language (1755).

Boswell highlights Johnson’s astonishing work ethic, hatred of pretension, and his belief that literature should serve moral ends.

A major portion of the book is simply Johnson talking — and Boswell listening. Boswell records Johnson’s wit, his thunderous moral pronouncements, his prejudices, his tenderness, and his ability to dominate any room. These conversations are the heart of the biography. They reveal Johnson’s mind more vividly than any formal essay.

Boswell devotes significant space to their shared travels, especially the 1773 journey to the Hebrides. These chapters show Johnson to be curious, open‑minded, occasionally irritable, and unexpectedly adventurous. The travel narrative also deepens their friendship — Boswell’s vanity and Johnson’s gruff affection play off each other beautifully.

Johnson’s Moral and Intellectual Character

Boswell presents Johnson as a devout Anglican, a defender of established institutions, a fierce opponent of slavery, a critic of luxury, and a man who believed deeply in duty, charity, and self‑discipline.

Yet Boswell also shows Johnson’s vulnerabilities: crippling melancholy, obsessive rituals, fear of death, and lifelong struggles with idleness.

This duality — strength and fragility — is central to the portrait.

Boswell records Johnson’s prayers, letters, and reflections on mortality with great tenderness. Johnson dies in 1784, surrounded by friends, after a final period of intense religious devotion.

Boswell’s genius lies in capturing conversation as literature, revealing character through small details, and refusing to hide his own foibles.

Boswell’s Life remains unmatched because it offers the most vivid portrait of a great mind ever written, a model of biographical intimacy, and a study of friendship between two very different men. It is both a historical document and a work of art.

End quote.

I cannot end this post without a few quotes from Boswell’s book.

-

- “Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it.”

- “The true, strong, and sound mind is the mind that can embrace equally great things and small.”

- “A man is seldom more innocently employed than when he is making money.”

- “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.”

- “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.”

(Boswell notes that Johnson meant false patriotism, not genuine love of country.) - “A decent provision for the poor is the true test of civilization.”

- “Integrity without knowledge is weak and useless, and knowledge without integrity is dangerous and dreadful.”

- “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.”

- “The only end of writing is to enable the readers better to enjoy life, or better to endure it.”

- “We are all prompted by the same motives, all deceived by the same fallacies, all animated by hope, obstructed by danger, entangled by desire, and seduced by pleasure.”

- “Almost every man wastes part of his life in attempts to display qualities which he does not possess.”

- “A man has no more right to say an uncivil thing than to act one.”

- “To cultivate kindness is a valuable part of the business of life.”

- “The mind is enlarged by knowledge, but it is not ennobled unless by virtue.”

- “Self-confidence is the first requisite to great undertakings.”

- “A man should keep his friendships in constant repair.”

- “Life affords no higher pleasure than that of surmounting difficulties.”

- “We are not to judge of the feelings of others by what we should feel in their place.”

- “He is not only dull himself, but the cause of dullness in others.”

- “That man has a great deal of brass, but no gold.”

- “Sir, your manuscript is both good and original; but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good.”

- “Sir, he reasons from premises which he does not understand to conclusions which do not follow.”

Time for music. Enjoy.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.

]]> Belgian cartoonist Philippe Geluck in his 1995 book Ma Langue au Chat wrote, “La mort, c’est un peu comme la connerie. Le mort, lui, il ne sait pas qu’il est mort . . . ce sont les autres qui sont tristes. Le con c’est pareil.”

Belgian cartoonist Philippe Geluck in his 1995 book Ma Langue au Chat wrote, “La mort, c’est un peu comme la connerie. Le mort, lui, il ne sait pas qu’il est mort . . . ce sont les autres qui sont tristes. Le con c’est pareil.”

Ricky Gervais adapted that insight. In October 2013 he wrote on twitter, “When you are dead, you do not know you are dead. It’s only painful & difficult for others. The same applies when you are stupid.”

Being stupid is not a crime. But beyond a certain point, people with very low IQ damage society. Their retardation is pernicious, particularly if they occupy positions of power and influence. Here’s a recent example.

Senator Josh Hawley questioning one Dr. Verma.

Doesn’t Verma have any friends and family who would tell her to not embarrass herself so much in public? She should take a few lessons from the little boy in the 1990 movie Kindergarten Cop.

A five-year old could have answered that question without hesitation. But Verma couldn’t. She is pathetic.

]]>

AI agents are the coolest innovation of our modern world. Every time you turn around, one more appears. It’s becoming hard to keep up with the advances. I am amazed. So should you be. Just for fun, I gave grok a simple prompt: “Summarize Atanu Dey’s views on Gandhi.”

Here’s the response. Begin quote:

Atanu Dey, an economist and classical liberal, holds highly critical and negative views on Mahatma Gandhi (whom he often refers to as Mohandas K. Gandhi to reject the “Mahatma” title as inaccurate and undeserved).

Based on his blog posts, X (formerly Twitter) statements, and writings, Dey portrays Gandhi as one of the most harmful figures in history, responsible for perpetuating India’s poverty, misery, and underdevelopment. He dismisses Gandhi’s deification as a myth propagated for political control and argues that Gandhi’s ideas and actions were delusional, manipulative, and evil. Below is a structured summary of Dey’s key opinions across themes, drawn from his own content.

On Gandhi’s Character and Personal Traits

Dey describes Gandhi as vain, egotistical, delusional, and ignorant, claiming he fancied himself an expert in economics, history, science, and morality despite lacking knowledge or training. For instance, Gandhi allegedly believed earthquakes were divine punishment for social evils like untouchability.

Dey calls him “one of the world’s greatest egotists,” a “tyrannical control freak,” and a “cunning” manipulator who used threats of self-harm (like fasting) as blackmail to impose his will. He accuses Gandhi of being a “sexual deviant” tormented by “abnormal appetites” and an “unhealthy fascination with matters sexual,” citing behaviors like sleeping naked with young women in his ashram while preaching celibacy to others. Dey quotes the Prime Minister of Travancore calling Gandhi “a most dangerous, semi-repressed sex maniac” and suggests his perversions drove many actions.

Additionally, Dey labels Gandhi a “racist and casteist,” noting his views that Africans were racially inferior to Caucasians and Indians, and his promotion of “Harijan” (people of God) as elevating one caste while associating others with the devil. He also calls Gandhi a “crypto Christian” who hypocritically advocated non-violence while supporting British wars.

Dey expresses personal disdain, stating, “I have a visceral hatred of Gandhi,” and compares him to an “evil genius” whose self-hatred (stemmed from sexual obsessions) led to hatred of Hindus. He argues Gandhi’s “good intentions” were indistinguishable from malice, making him “the most evil person who has ever lived so far,” causing more misery than Stalin, Mao, or Hitler.

On Gandhi’s Actions and Ideology

Dey rejects Gandhi’s philosophy as harmful and hypocritical. He criticizes non-violence as a “cunning device” dressed in piety, used to discourage retaliation—e.g., advising Hindus not to harbor anger against Muslims intent on destroying them, or telling Hindu women to commit suicide if raped by Muslims. Gandhi reportedly urged Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs in Lahore during Partition violence to “die with what you think is the dying city” rather than flee. Similarly, he advised Jews in Nazi Germany to commit suicide for a “moral victory.” Dey mocks Gandhi’s famous quote, “An eye for an eye will make the whole world blind,” as “absolute feces” and “moralistic stench.”

On economics, Dey condemns Gandhian self-sufficiency as preserving “poverty in body and mind,” insisting humans are interdependent. He argues Gandhi opposed industrialization, railways, and mass production as “evil,” promoting village economies and manual toil as virtuous while viewing comfort and prosperity as sinful. Dey calls this ideology a “defunct” disaster that “paved the way [to] India’s descent into hell,” comparable to communism’s havoc.

Politically, Dey sees Gandhi as a British “stooge” and “useful idiot” who delayed independence by cooperating with them—e.g., recruiting Indians for British wars and keeping natives in check. He claims the Khilafat movement encouraged Muslims to kill non-Muslims. Dey dismisses Gandhi’s role in independence as “Mi-ni-mal” (quoting Clement Attlee), attributing freedom more to economic unviability for Britain and figures like Subhas Chandra Bose. He accuses Gandhi of forcing Jawaharlal Nehru (whom “no one wanted”) into power over Vallabhbhai Patel, leading to socialist policies and enduring poverty.

On Gandhi’s Impact and Legacy

Dey blames Gandhi for India’s “pathetic and perennial” poverty, calling him the “Father of Indian poverty and endless misery” and “god’s curse on India.” He argues Gandhi’s promotion of Nehru created “British Raj 2.0″—a tyrannical, bureaucratic system where Indians became subjugated by homegrown overlords, denying true freedom despite independence. This “command, control, license, permit, quota” government enriched rulers while impoverishing people, condemning billions to suffering. Dey claims foreign powers like the US invoke Gandhi to lecture India on non-violence and poverty, preventing it from arming or prospering, while hypocritically not applying the same to themselves.

He warns that venerating Gandhi keeps India irrelevant and poor, urging rejection of his myth: “Until and unless Indians know the truth about the so-called ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi, I am afraid that India will continue to be pathetically and perennially poor.” Dey notes Gandhi was not awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, sarcastically calling it a “pity” given later recipients like Kissinger and Arafat.

In summary, Dey’s views are unrelentingly negative, framing Gandhi not as a hero but as a delusional tyrant whose legacy is a barrier to India’s progress. He emphasizes, “All things considered he was not good for India.”

End quote.

I would say that that’s a fair summary. Frankly, I would not have been able to summarize my writings so well. I am amazed, as I said before.

Next, I will post what grok’s response was to my query, “What are Atanu Dey’s views on Nehru?”

]]>

“General equilibrium is the statement that all the different parts of the economy influence each other, even if it’s remote, like mortgage-backed securities and their demands on automobiles.” — Kenneth Arrow

Economists rediscover Indra’s jewel net.

During my graduate school days at Berkeley, I once asked my advisor how she would characterize me. She replied, “You’re an old-world liberal. A classical liberal.” It took me several years to fully understand what she meant and how accurate her assessment was.

The dharmas (Sanatan dharma, Buddha dharma, and Jain dharma) have the concept of reincarnation. Some elements of a particular consciousness get transmitted from one life to another and are reborn in another particular consciousness. It’s possible. And there’s quite a lot of evidence that it could be true.

When I began learning about classical liberal ideas, it was as if I already knew them implicitly but was now merely learning the associated vocabulary. I conjecture that I am in some sense a reincarnated classical liberal.

My advisor was a tough woman. She had served her time in the Israeli army before getting her economics PhD. She was an expert on computable general equilibrium models. (See the notes to this post for a description of CGE models) I looked into them for a few months and concluded that they did not interest me. I was more of a price theory person, not into general equilibrium.

That said, GE is a fascinating concept that is (at least to some) intuitive. It was to me. I could see why it made sense. Every well-educated person should know what it is. Fortunately, these days knowing the basics of any topic is trivial: you ask an AI agent. But of course, you have to know what to ask. Education is what you need to be able to use AI agents.

General equilibrium (GE) models analyze how multiple markets interact simultaneously to determine prices, quantities, and allocations across an entire economy.

In the notes to this post, I list some of the important and influential GE models, based on their widespread use in theory and policy. I’ve focused on the classics and key modern variants, with brief descriptions of their core features and significance. (Disclosure: Written with a little help from my friend Grok.)

I also asked Grok for quotes related to GE. I used one of the quotes as an epigraph to this post.

“While economic theory in general may be defined as the theory of how an economic condition or an economic development is determined within an institutional framework, the welfare theory deals with how to judge whether one condition can be said to be better in some way than another and whether it is possible, by altering the institutional framework, to achieve a better condition than the present one.”— Kenneth Arrow

“The general theory of economic equilibrium was strengthened and made effective as an organon of thought by two powerful subsidiary conceptions — the Margin and Substitution.”— John Maynard Keynes

“We know, in other words, the general conditions in which what we call, somewhat misleadingly, an equilibrium will establish itself: but we never know what the particular prices or wages are which would exist if the market were to bring about such an equilibrium.”— Friedrich August von Hayek

“Nothing has done more to render modern economic theory a sterile and irrelevant exercise in autoeroticism than its practitioners’ obsession with mathematical, general-equilibrium models.”— Robert Locke

“Economists are good (or so we hope) at recognizing a state of equilibrium but are poor at predicting precisely how an economy in disequilibrium will evolve.”— Andreu Mas-Colell, Michael D. Whinston, and Jerry R. Green

I like Robert Locke’s delicate phrasing: “a sterile and irrelevant exercise in autoeroticism.”

The last quote above is by MWG, the authors of a grad-level micro econ textbook. That book is the stuff that nightmares are made of. (I mentioned that book in an Oct 2020 post. I also mention fixed point theorems in that post. The MWG book is available from the Oxford University Press for the low, low price of $159 plus tax and shipping.)

This post was about general equilibrium. It still is. But I somehow digressed into reincarnation. So let’s listen to a favorite song that is about reincarnation, shall we? Al Stewart begins his “One Stage Before” with —

It seems to me as though I’ve been upon this stage before

And juggled away the night for the same old crowd

These harlequins you see with me, they too have held the floor

As here once again they strut and they fret their hour . . .

Strut and fret their hour! Nicely done, Mr Stewart, very nicely done. No doubt taken from Macbeth’s soliloquy, “. . . A poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage . . .”

That’s it for now. Below is the promised intro to general equilibrium theories. Enjoy.

Image at the top of the post credit Indra’s Jewel Net. Indra’s net is an illustration of a GE model.

NOTES on General Equilibrium models

- Walrasian Equilibrium Model

Developed by Léon Walras in the late 19th century, this is the foundational static GE model. It assumes competitive markets where prices adjust via a hypothetical “tâtonnement” (groping) process until supply equals demand in all markets simultaneously, achieving equilibrium. Key features include price-taking agents, no production in basic versions (later extended), and Pareto efficiency under certain conditions. Its importance lies in establishing the concept of interdependence across markets, influencing microeconomic theory and proofs of equilibrium existence. It’s widely used to study resource allocation, tax incidence, and policy impacts in areas like trade and public finance.

- Arrow-Debreu Model

Formalized by Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu in the 1950s, this axiomatic extension of the Walrasian model incorporates uncertainty, time, and space through “contingent commodities” (e.g., goods delivered at specific times, locations, or states of nature). It assumes complete markets, convex preferences and technologies, and proves the existence and efficiency of competitive equilibria using fixed-point theorems. Significance: It provides a rigorous mathematical foundation for GE theory, enabling analysis of intertemporal allocation, risk-sharing, and welfare theorems. This model underpins much of modern finance and macroeconomics, though it’s criticized for unrealistic assumptions like perfect foresight.

- Overlapping Generations (OLG) Model

Introduced by Paul Samuelson in 1958 (building on earlier work by Maurice Allais and Irving Fisher), and extended by Peter Diamond in 1965 to include production. In this dynamic GE framework, agents live finite lives (typically two periods: young and old), overlapping across generations, with decisions on saving, consumption, and work affecting intergenerational resource transfers. Key features include potential for multiple equilibria, dynamic inefficiency (e.g., over-saving), and no infinite horizons. Its importance is in modeling life-cycle behavior, demographic transitions, Social Security, and economic growth; it explains phenomena like money as a store of value and challenges the Pareto efficiency of equilibria in infinite-agent settings. OLG models are crucial for studying fertility, human capital, and long-run dynamics absent in static models.

- Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) Models

Evolving from Walrasian and Arrow-Debreu foundations, CGE models were pioneered in the 1960s-1970s. These are numerical, data-driven simulations that calibrate economic theory to real-world data (e.g., via Social Accounting Matrices) to compute equilibria under policy shocks. Features include sector interdependencies, elasticities for substitution, and flexibility for taxes, trade, or externalities; they can be static or dynamic. Significance: Used by governments, international organizations (e.g., World Bank, IMF), and academics for policy analysis, such as fiscal reforms, trade agreements, or climate impacts. CGE bridges theory and empirics, revealing indirect effects that partial equilibrium misses.

- Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) Models

Developed in the 1980s-1990s, building on real business cycle theory and incorporating elements like sticky prices. DSGE integrates microfoundations with stochastic shocks (e.g., technology or demand) in a dynamic GE setting, often with infinite-lived agents optimizing under rational expectations. Variants include New Classical (frictionless markets) and New Keynesian (with rigidities like wage stickiness). Importance: Dominant in modern macroeconomics for forecasting, monetary policy (used by central banks like the Fed), and analyzing business cycles. It micro-founds aggregate behavior, allowing simulations of shocks, but faces criticism for oversimplifying real-world frictions post-2008 crisis.

These models form the backbone of GE theory, evolving from abstract static frameworks to practical tools for policy.

]]>

“‘I sometimes think,’ said the Eternal, ‘that the stars never shine more brightly than when reflected in the muddy waters of a wayside ditch.'”

Maduro

On January 3rd, the US Delta Force captured Nicolás Maduro, the dictator of Venezuela, in an overnight operation in Caracas that caught Maduro off-guard. The action was planned for months and executed flawlessly without a single US casualty.

Time.com reports: “President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela and his wife, Cilia Flores, were seized in a pre-dawn raid in Caracas by American special operations forces, the culmination of months of covert intelligence work and steadily escalating military pressure ordered by President Donald Trump to oust the authoritarian leader. The operation, officials said, unfolded in less than half an hour overnight but drew on weeks of rehearsals and a vast armada of aircraft and intelligence assets that tracked Maduro’s behavioral habits.”

Maduro and his wife were transported to New York to face drug‑trafficking charges. It appears to be the stuff that military action movies are made of.

No doubt there will be a movie soon.

Venezuela has the largest proven crude oil reserves in the world. The crude is heavy and requires petroleum refineries that can handle it. Venezuela does not have the capacity and depended on the US gulf coast refineries.

Resource Curse

Given its natural resource endowment, Venezuela could have been one of the richest economies in the world. But as is unfortunately quite common, some countries are doomed to fail because of what is called a “resource curse,” or the “paradox of plenty.”

This is the surprising phenomenon where countries rich in natural resources — such as oil, gas, or minerals — tend to experience slow or even negative economic growth, weaker development outcomes, higher corruption, and high inequality. The intuitive expectation is that abundant resources would bring prosperity, but the opposite often occurs.

This is due to factors like over-reliance on a single commodity (vulnerability to price swings), weak institutions and corruption. Resource revenues can fuel rent-seeking rather than productive investment and the neglect of other economic sectors. Venezuela is a textbook example of the resource curse.

Dutch Disease

Closely related to the resource curse is what economists call “the Dutch disease.” It occurs when a sudden boom in one sector (typically natural resource extraction) causes the national currency to appreciate sharply. This makes other export sectors (like manufacturing or agriculture) less competitive internationally, leading to their decline or stagnation. The term originated from the Netherlands’ experience after discovering large natural gas reserves in the 1960s, which boosted the guilder but harmed manufacturing exports.

Many countries suffer from resource curse and Dutch disease, but good institutions, economic diversification, and prudent management (like Norway’s sovereign wealth fund) can help avoid or mitigate them.

Institutions

Institutions matter fundamentally for the health of an economy. The constitution is an institution that provides the foundation upon which other institutions such as the government and the economic order (free market or command-and-control) are built.

Institutions are built by people. If the country has the good fortune to have good leaders, then it prospers regardless of how much or how little its resource endowment is. Conversely, poor leadership invariably condemns the people to misery.

Some countries escape the resource curse. Norway, richly endowed, is a great example. In contrast to that, many African countries suffer immensely. Then there’s Singapore. It got lucky that Lee Kuan Yew was in charge since its inception. He recognized that Singapore had very little in terms of natural resources. Therefore, it had to rely on being productive.

Venezuela

The pity is that the people of Venezuela have been suffering for decades. It relied on world crude oil prices, and its fortunes rose and fell with it. During the tenure of Hugo Chavez, oil prices were high and the people enjoyed lavish subsidies from the Chavez administration, corrupt though it was.

Maduro took control upon the death of Chavez in 2013. That coincided with the precipitous decline of oil prices and with it the decline in the living standard of Venezuelans. It’s a fascinating story of how to destroy an economy using the age-old socialist formula.

See this video for a quick review of the story: “How to bankrupt a country in 5 easy steps.” It may not be the most accurate but it should do for now.

With that, let’s move on to opinion. All things considered, it was time for Venezuela to have an external shock. The system was stuck in a very low equilibrium and an external shock often improves matters.

It was unlikely that any Venezuelan leader would have the foresight to change the trajectory of the economy. Trump has taken the first step of taking control of Venezuela. He wants the US to manage its oil resources. Is that good for Venezuelans? I think it is.

At the very least, the people will get some relief. Granted that the US is not a benevolent power and further granted that the US military-industrial complex will be the major beneficiary of the capture of Venezuela’s oil wealth, it is undeniable that the people will not be any worse off than they are now.

In a perfect first-best world, Venezuelan leaders would have been benevolent and would have managed their national wealth for the benefit of their people instead of being a dictatorial kleptocracy. Since it is a second-best world, what they had was a kakistocracy — where the least qualified and the most corrupt hold power.

The situation is bad. But we have to ask: It’s bad compared to what? Furthermore, we have to keep in mind that in our imperfect real world, there are no perfect solutions, only trade-offs.

Random Draw

Life’s a random draw. That’s true at the level of the individual and at the level of the collective. Some countries draw good cards. Singapore did. So did the United States at its founding. Other countries have no such luck. India drew a terrible hand in 1947. Over the decades, I estimate a couple of billion Indians have needlessly suffered immensely.

Venezuela is a small country. Current estimates place it around 30 million people. That’s the same as its population a decade ago. People were forced to migrate to neighboring countries in search of relief in the recent few years. The damage has been limited compared to the damage that India has suffered. But I digress.

Oil

Venezuela’s prospects have improved because of Trump’s move. Trump of course is not benevolently motivated. He is too stupid and too megalomaniacal for that. Whatever his motivations, Trump has finally done something that is good for the world. Thank goodness for small mercies.

Oil is a valuable resource but it does have an expiry date. I expect that in about 20 years or so, the demand for oil will fall to the point that very little of it will be extracted. The major source of energy will nuclear (fission and fusion). Therefore, it is in the interest of oil-rich countries to extract and sell as much oil as they can.

The exploitation of Venezuelan oil will be good for the people. Not just that, it will be good for the world economy. It will boost world economic growth.

Stuff in the ground is not wealth. It’s just stuff. Stuff becomes wealth when it is used for productive purposes. Chevaz and Maduro buried the economy. Time to dig it out and free the people to enjoy their inheritance.

Let’s close with a song.

Thank you, good night and may your god go with you.

]]>

December 25th is celebrated as the birthday of the most famous Jew ever, though Jews don’t consider Jesus the son of their god. They continue to wait for the messiah which they have been doing for a few thousand years. It’s interesting that Christians worship a Jew but have been persecuting Jews for over 2000 years. I find that very puzzling.

Christians make up approximately 31% of the world’s population, making Christianity the largest religion globally. Therefore, Christmas is a big deal in a significant part of the world and has been so for centuries.

Christmas is also celebrated in India although Christians constitute a low single-digit percentage minority of Indians. Christmas is big in India because Christianity was the religion of the people who colonized India for a couple of centuries. Indians are given to bending over to their rulers’ creed, be that Islamic or Christian. Christians and Muslims don’t much care for celebrating the major events of the dharmic traditions, but Hindus make a big show of being inclusive.

The sight of many Indian service industry workers going around in Santa Claus costumes has to the most shocking display of ignorance and servitude imaginable. It is culturally and climatically incongruent. The sight of people walking around in red suits more suited to freezing Nordic weather than to the sweltering heat of Mumbai is grotesque.

I love Christmas in America. One of my favorite things to do during the season in the SF bay area is to drive around those parts of town which put extra effort in decorating their houses with Christmas lights. The Willow Glen neighborhood in San Jose is special for its elaborately lighted homes, particularly around Glenbrook Ave & Lincoln Ave.

Here’s a picture from Christmas 2023.

Santa Claus has his origins in Saint Nicolas, a real historical person who was a Greek Christian bishop who lived around 270–343 CE. The modern Santa is a mainly American invention. In the 1930s, US department store advertising and Coca-Cola campaigns popularized the red suit. Santa became a global symbol of holiday consumerism, joy, and generosity detached from any explicit religious meaning.

A favorite contemporary essayist, David Sedaris, did a hilarious essay on Santa Claus. He read it live at the Carnegie Hall a few years ago. It is titled “Six to eight black men.” Here it is in three parts. Listen. Money back guarantee that you will like it.

And a bit of Christmas music.

That’s it for now. Merry Christmas to you and your loved ones.

Slavery is as old as civilization. As hunter-gatherers, humans could not have held slaves. Only with the advent of settled agriculture it became possible for some people to own other people. Every civilization has had the institution of slavery although one may get the impression that only the whites have enslaved blacks, and that the Americans in particular are guilty of the crime of slavery.

Slavery is as old as civilization. As hunter-gatherers, humans could not have held slaves. Only with the advent of settled agriculture it became possible for some people to own other people. Every civilization has had the institution of slavery although one may get the impression that only the whites have enslaved blacks, and that the Americans in particular are guilty of the crime of slavery.

Although that’s a common enough misconception, there’s no justification for it in this day of easy access to historical information. A quick question to any of the AI engines is all you need to learn about the awful history of slavery.

The Atlantic slave trade is the most cited but was neither unique nor even the worst. During the Atlantic slave trade, which lasted from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, around 12 million Africans were put on slave ships, sailed across the Atlantic Ocean and sold into slavery. Of this approximately 600,000 were transported to north America, which means that about 5% of all African slaves from the Atlantic slave trade were brought to America.

The Europeans did not capture slaves in Africa. The job of capturing Africans and selling them to Europeans was done by Africans. Africans enslaved Africans. They were the original slavers.

Did you know that blacks owned slaves in the American south? Only about two or three percent of Americans in the southern American states owned slaves and a good fraction of the slave owners were black.

The monotheistic religions are quite supportive of slavery. Judaism, Christianity and Islam have rules on how to treat slaves. They don’t have any prohibition on slavery but they do have all sorts of dietary prohibitions. That should tell you a lot about how enlightened those creeds are.

Even before the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Arabs captured millions of slaves around the world. The etymology of the word slave is revealing. It comes from Slav because many Slavs were sold into slavery.

The Arab slave trade, also known as the Trans-Saharan, Red Sea, or Indian Ocean slave trade, was a system of enslavement primarily conducted by Muslim traders and states from the 7th century AD through the 20th century, spanning over 1,300 years. It involved the capture, transport, and sale of slaves from sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe (such as Slavs and Circassians), the Caucasus, Central Asia, and parts of India and Southeast Asia.

I have appended a brief note composed by grok (lightly edited) about the Arab slave trade at the end of this piece. It’s a horror show. Read 15 Forgotten Slave Trades Outside the Atlantic World

A friend asked me to write about the economics of slavery. Slavery is in essence robbery. It involves the use of force to deprive a person of the use of his body and mind for his own purposes. Slavery is immoral, for certain but like theft or robbery, it’s not economically inefficient in its first-order effect. If I steal $10 from you, your loss is my gain. That is Pareto efficient because that theft in itself did not lead to any loss of the total amount of money; it only affected the distribution.

The second-order effects of theft or robbery are more likely to lead to social losses. If your property is likely to be stolen or property rights are not enforceable, then you may not put in the effort to create wealth.

If the product of your labor is going to be stolen, you will not work as hard and therefore society loses wealth. That makes slavery economically inefficient. In other words, slavery is beneficial to the slave owner but the gain to the slave owner is lower than the loss to the enslaved person.

Slavery ended because the economics of slavery changed. It is true that the abolitionists did have a hand in it. But in the end, economic forces abolished slavery in the developed world more than any humanitarian forces.

Quick lesson. As you know, economics is called the “dismal science.” Economics earned its “dismal” reputation by standing against slavery and for human equality, even when that stance was unpopular. Economists generally held that people of all races were fundamentally similar, entitled to liberty.

The phrase “dismal science” was coined by the Scottish historian and essayist Thomas Carlyle in his 1849 essay “Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question.” He used it derogatorily to criticize economics (then called political economy) for its opposition to his pro-slavery views.

He argued that blacks were inherently idle and inferior. He mocked philanthropists and economists who advocated free labor markets. Classical economists like John Stuart Mill responded vigorously. Mill’s 1850 rebuttal, “The Negro Question“, defended emancipation and free labor.

A widespread myth attributes the phrase to Carlyle’s reaction to Thomas Robert Malthus’s pessimistic predictions of population growth outstripping resources, leading to famine and misery. While Carlyle did criticize Malthus elsewhere, the specific term “dismal science” originated in the slavery debate, not population theory.

The end of traditional chattel slavery (legal ownership of people as property, inheritable across generations) began to end in the Western world around the beginning of the 19th century but did not end in the Islamic world until the middle of the 20th century.

Though slavery is abolished around the world, it still exists in the world today. Modern forms of slavery—as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO)—persist in many Muslim-majority countries. These include forced labor, human trafficking, debt bondage, forced marriage, and exploitative domestic work, affecting an estimated 50 million people globally in 2023, with disproportionately high prevalence in some regions of the Islamic world.

A clue to what explains the end of slavery is contained in the fact that the beginning of the end of slavery coincided with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England and then spread to the rest of the industrialized world, and then to the developing world.

Slavery was abolished in the US with the end of the American Civil war in 1865. (I recommend Ken Burns’ documentary “The Civil War.” It is available free on YouTube.) The southern states did not wish to be forced by the northern states to abolish slavery. The southern states were economically dependent on slave labor to work their cotton plantations. Eli Witney’s cotton gin made it efficient to separate the cotton seeds from the fiber but picking cotton required labor.

The industrial revolution began in the second half of the 18th century. Between 1760s and 1780s, James Watt improved Thomas Newcomen’s 1712 steam engine. That powered the industrial revolution with coal as the major source of energy.

About a century later, in 1859, commercial oil wells came into operation in Pennsylvania. That was the beginning of the displacement of human muscle power with power from crude oil. It became possible — not just morally justifiable — to end slavery.

Consider this. A barrel of oil has roughly 1700 kwh energy. That’s equivalent to five human-years of work. The use of oil, coal and natural gas provides the equivalent of ~500 billion humans’ worth of energy. On average, every human alive today has around 50 “slaves” working for him or her. It would be economically inefficient to enslave people.

We don’t need slaves because we have technology. And as we get more technology, the world will become a lot better. “The better angels of our nature” is credited for our moral progress but a look behind the curtain will reveal that technology has made it possible for us to become good.

Time for a bit of music.

That’s it for now. Thank you, good night, and may your god go with you.

Appendix: The Arab Slave Trade

The Arab slave trade, also known as the Trans-Saharan, Red Sea, or Indian Ocean slave trade, was a system of enslavement primarily conducted by Muslim traders and states from the 7th century AD through the 20th century, spanning over 1,300 years. It involved the capture, transport, and sale of slaves from sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe (such as Slavs and Circassians), the Caucasus, Central Asia, and parts of India and Southeast Asia. Key routes included overland caravans across the Sahara Desert to North Africa, maritime paths via the Red Sea to Arabia, and the Indian Ocean to regions like Zanzibar, Oman, and the Persian Gulf.

Slaves were sourced through raids, warfare, kidnappings, and tribute from African kingdoms, with major markets in cities like Cairo, Mecca, Khartoum, and Zanzibar. Estimates suggest 11–17 million Africans were enslaved over the centuries, with additional millions from other regions (e.g., up to 1.25 million Europeans via the Barbary Coast between 1530 and 1780).

High mortality rates occurred during transport, with up to 50% dying from exhaustion, disease, or exposure.

Slaves were used for domestic service, concubinage (especially women, who comprised a higher proportion), military roles (e.g., Mamluk soldiers or Janissaries), eunuch guards (many males were castrated), and limited agricultural labor, as large-scale plantations were discouraged after major revolts like the Zanj Rebellion (869–883 AD).

Islamic law regulated slavery, prohibiting the enslavement of fellow Muslims but allowing it for non-Muslims captured in jihad; it encouraged manumission as an act of piety, and children born to enslaved concubines and free Muslim fathers were often free and legitimate.

Racial prejudices existed, particularly against Black Africans, but slavery was not strictly racialized in doctrine.

Abolition was gradual, influenced by Western pressure, with bans in places like Zanzibar (1909), Saudi Arabia (1962), and Mauritania (1981, though enforcement lagged), and some modern revivals attempted by jihadist groups.

Contrast with the Atlantic Slave Trade

The Atlantic slave trade, driven by European powers (primarily Portugal, Britain, Spain, France, and the Netherlands), lasted about 400 years from the 15th to 19th centuries, peaking in the 18th century. It focused exclusively on Africans from West and Central Africa (e.g., regions like Angola, the Bight of Benin, and the Gold Coast), with an estimated 10–12.8 million people forcibly transported across the Atlantic Ocean in the infamous Middle Passage, where 12–15% died en route from disease, overcrowding, and abuse, contributing to total deaths of 4–5 million including pre-shipment losses.

Slaves were destined for the Americas, with Brazil receiving about 4.8 million (38%), the British Caribbean 2.3 million (18%), and the U.S. around 300,000 directly (plus internal trade).

They were primarily used for intensive plantation labor in crops like sugar, cotton, tobacco, and coffee, under a system of hereditary, racialized chattel slavery where enslaved status passed through the mother, and manumission was rare.

Key contrasts

-

-

- Duration and Scale: The Arab trade endured far longer (1,300+ years vs. 400) but at a lower annual intensity, with similar total African victims (11–17 million vs. 10–12.8 million).

- The Atlantic was more concentrated and industrialized, driven by colonial demand.

- Sources and Routes: Arab trade drew from diverse regions (Africa, Europe, Asia) via land and sea routes; Atlantic was limited to African coastal areas and transoceanic voyages.

- Demographics and Treatment: Arab trade favored females (2:1 ratio) for concubinage and castrated many males, leading to limited reproduction and integration through conversion/manumission; Atlantic favored males (2:1) for labor, with high reproduction in the Americas but brutal, non-integrative conditions and explicit racial hierarchies.

-

Uses and Economy

Arab slaves often filled domestic, military, or sexual roles with some social mobility (e.g., Mamluks rising to power); Atlantic emphasized exploitative agricultural and mining labor with no upward paths.

Abolition and Legacy

The Atlantic ended earlier due to humanitarian campaigns (e.g., British ban 1807, U.S. 1865), while the Arab trade persisted longer without equivalent internal movements, only curbed by external pressure.

The Atlantic created a large African diaspora in the Americas with lasting racial impacts, whereas the Arab trade’s effects are more integrated into Middle Eastern and North African societies, though less publicly acknowledged.

]]>

I looked at the title of this post and realized that the two words in it differ only in one letter. Funny, isn’t it? It’s going to be a sunny Sunday. Funny and sunny rhyme. I’m quite the wordsmith today. Which reminds me that I learned William Wordsmith’s 1804 poem Daffodils by heart in middle school and can still recite it by heart. Its final lines are the best:

“And then my heart with pleasure fills

And dances with the daffodils.”

So, what’s happening? Yesterday Courtenay drove down from Oakland to visit for a bit. Hadn’t seen her since January. She had tales of woe. Got fired from her job a few days ago; car’s leaking oil and could set her back a few thousand in repairs; husband and teenage son are tearing around the house breaking stuff; bills to pay; neighbors are being jerks, etc. But she’s a good sport and laughs it off.

You can take the girl out of Toledo, Ohio but you cannot take the Toledo, Ohio out of the girl, is what they say.

She has this something for her Honda delSol. She’s fixated on that car since she got it in 1993. That’s an unbelievable 32 years — considering that American’s replace their cars every seven years or so. She loves that wreck. I have borrowed the car occasionally. One time I drove it all the way to the Grand Canyon and back via Los Angeles.

Here’s a picture of the delSol. Guess what the California vanity license plate reads. Click on the image to get a better look at it.

Here’s a picture of the delSol. Guess what the California vanity license plate reads. Click on the image to get a better look at it.

It’s quite clever, actually. Notice “sol” and “soul” rhyme. But the other bit is even cleverer. Think about it. Fabulous prizes if you figure it out. The answer will be revealed at the end of this post.

Back in the day, I too owned a rather clever California license plate: “NU DEY”.

Back in the day, I too owned a rather clever California license plate: “NU DEY”.

Seeing it people may have thought that it was a cute way of writing “new day” but it is actually my name.

To my family and friends, my name is “Nu” — which in Bengali is called a dak naam. Every Bengali has a formal name (the first name or the given name or bhaalo naam) but is called by the informal name. My parents used to call me Nu, and I later was given Atanu as my first name.

Some of my friends have my permission to call me Nu. Yoga, for instance, calls me “Nu da” (da is short for dada or elder brother) and his two kids call me “Nu da uncle.” Funny.

Cars. How about a song that has something to do with cars? Here’s just the song we want — Drive by The Cars.

Who’s going to drive you home, tonight?

Important question. But the urgency of that question does come down a notch these days of robotaxis and self-driving cars. A few weeks ago, I got to have my first Waymo ride around Mt. View, CA. Here’s a short clip I took as I rode shotgun in the cab.

Notice that up here in California, fall begins and ends rather late. Even in late November, you can see lovely fall colors. Along the north east, fall end by late September.

I am quite simply impressed when I first encountered the most rudimentary form of self-driving — cruise control. “Wow! You don’t have to keep your foot on the gas and yet the car keeps going at the same speed. What will they think of next!” The first car with cruise control I got was a while back in 1989 — which was sort of rare then.

The Honda CR-V that I got in 2018 had what is called “adaptive cruise control.” It maintains the set speed but also adapts to traffic conditions by slowing down with slow traffic. The car also had “lane assist”: it would follow the lane. On road trips, ACC and LA were very useful. I could drive along for hours without actively driving for more than a few minutes. Not quite self-driving but definitely a huge improvement on having do for all the driving.

I believe that self-driving cars would be common in about 10 years in advanced industrialized countries; in underdeveloped countries, it may be another 10 years.

That would be a good thing since most people are lousy drivers. Indians, particularly, are the second worst. The worst? I think they say the Chinese are the worst.

Alright, time to wrap up. The song for today, most appropriately, is Lazy Day from the album On the Threshold of a Dream by the Moody Blues.

The answer to the license plate puzzle: it says, “ et soul”. Courtenay’s kids are half-French. The plate reads “heart and soul.” Told you it was quite clever.

et soul”. Courtenay’s kids are half-French. The plate reads “heart and soul.” Told you it was quite clever.

Happy Sunday!

]]>

Life is a random draw. Much of life is contingent and it’s like a random walk with many unpredictable twists and turns. Many unforeseen events have taken me down roads that I had no inkling about even a few months before I embarked on an adventure. One of those lucky turns happened around 33 years ago.

I was at the Sunnyvale Public Library, waiting in line to check out a few books. SPL was close to home. I would go there a few times a month. While waiting to check out books, I randomly picked up a book from a sorting cart. It was titled “Micromotives and Macrobehavior.” I glanced at a few paragraphs and decided to borrow the book.

That evening, I started reading the book. In a day, I had read the book. I found it fascinating. The author, it turned out, was someone named Thomas Schelling. He was an economist. It dawned on me for the first time that I was an economist. Until that point, I had not only not known what economics was but I had no idea that I was actually an economist.

A few months later, I was telling about that to a friend of mine, VA, in Palo Alto. He said, “Hey, I think you should get a Ph.D. in economics!” That planted a seed.

Years ago, I had enrolled for a Ph.D. in computer science at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. I was advanced in the program (“all but the dissertation”) when I visited a friend (same guy, VA) in Sunnyvale, CA, for the summer in 1994. I got to know many people. One of them said, “Hey, get a job.” So, I wrote up a resume and a week later I had a job at HP in Cupertino. (That HP site is where the Apple headquarters is now. Picture above.)

Years ago, I had enrolled for a Ph.D. in computer science at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. I was advanced in the program (“all but the dissertation”) when I visited a friend (same guy, VA) in Sunnyvale, CA, for the summer in 1994. I got to know many people. One of them said, “Hey, get a job.” So, I wrote up a resume and a week later I had a job at HP in Cupertino. (That HP site is where the Apple headquarters is now. Picture above.)

In a sense, I was not unfamiliar with the rigors of a Ph.D. program. But there was a little problem: I did not have any background in economics. Getting into a Ph.D. program in econ at a world-class university without any background is not an easy job. If I had been asked the simplest of questions — “Why does a demand curve slope downward?” — I would have replied “what’s a demand curve?”

Anyhow, my determination and persistence (unusual for me) paid off. UC Berkeley admitted me but I was told by the chairman of the admissions committee that I was most likely to fail out of the program.

As it happened, I did get through. My doctoral dissertation was on the Indian telecom sector. It investigated “the welfare consequences of the universal service obligation imposed cross-subsidies on the demand for telecommunications in India.”

I am pretty proud of that but I admit that now if I try to read my thesis, I can’t make head nor tail of it. Too much heavy mathematical modeling and then of course the econometrics is completely opaque. Anyway, I did learn a bit of economics at graduate school.

It all began with Thomas Schelling’s book. He was a brilliant man. Nine years ago, on Dec 13, 2016, Schelling passed away. I write to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to him.

It all began with Thomas Schelling’s book. He was a brilliant man. Nine years ago, on Dec 13, 2016, Schelling passed away. I write to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to him.

Here’s a brief summary of his work.

Thomas C. Schelling (1921–2016) was an American economist whose pioneering application of game theory to real-world strategic interactions profoundly shaped economics, particularly in understanding conflict and cooperation. He shared the 2005 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Robert Aumann for “having enhanced our understanding of conflict and cooperation through game-theory analysis.”

His key contributions are:

Strategy of Conflict and Bargaining (The Strategy of Conflict, 1960)

Schelling’s seminal book reoriented game theory toward mixed-motive situations, where parties have both conflicting and shared interests. He introduced concepts like:

Schelling’s seminal book reoriented game theory toward mixed-motive situations, where parties have both conflicting and shared interests. He introduced concepts like:

-

- Credible commitments: How promises and threats can be made believable (e.g., by irreversibly limiting one’s own options, such as “burning bridges”).

- Focal points (Schelling points): Tacit coordination without communication, where people converge on salient solutions (e.g., meeting in a city at a prominent landmark).

- Deterrence and brinkmanship: In nuclear strategy, the value of deliberate uncertainty or “threats that leave something to chance” to deter aggression.

These ideas influenced Cold War policies, arms control, and broader negotiations in trade, business, and international relations.

Models of Segregation (Dynamic Models of Segregation, 1971; expanded in Micromotives and Macrobehavior, 1978)

Schelling developed an early agent-based model showing how mild individual preferences for similar neighbors (e.g., wanting at least 30–50% like oneself) can lead to extreme macro-level segregation through “tipping points.” This demonstrated unintended emergent outcomes from individual “micromotives,” influencing urban economics, sociology, and behavioral economics. It highlighted how segregation persists without strong prejudice or external forces.

Applications

-

- Extended ideas in Arms and Influence (1966) to coercion and diplomacy.

- Contributed to behavioral economics by exploring self-commitment (e.g., in addiction or decision-making) and coordination problems.

- Later work touched on climate change (advocating carbon taxes), health policy, and global issues like nuclear taboos.

Schelling’s accessible, non-mathematical style—relying on logical reasoning and vivid examples—made his insights widely influential across economics, political science, and beyond, bridging theory with practical policy. His work remains foundational in strategic thinking.

Be well, do good work and keep in touch.

Previous 2005 post on the passing of Thomas Schelling.

]]>

I love homemade bread, and I love red wines. I am partial to the cabernet sauvignon, merlot and pinot noir varieties. The first two are from the Bordeaux and the third from the Burgundy regions of France. They are also great places to visit, as I did many years ago.

I love homemade bread, and I love red wines. I am partial to the cabernet sauvignon, merlot and pinot noir varieties. The first two are from the Bordeaux and the third from the Burgundy regions of France. They are also great places to visit, as I did many years ago.

My close friend and host — A in San Jose — occasionally bakes bread at home. A few days ago, we had some fresh out of the oven bread with Kerrygold Irish butter (from Costco, where else!) and paired it with some cabernet sauvignon (probably from Trader Joe’s.) The picture of the bread and wine appears at the top of this post. Click to embiggen.

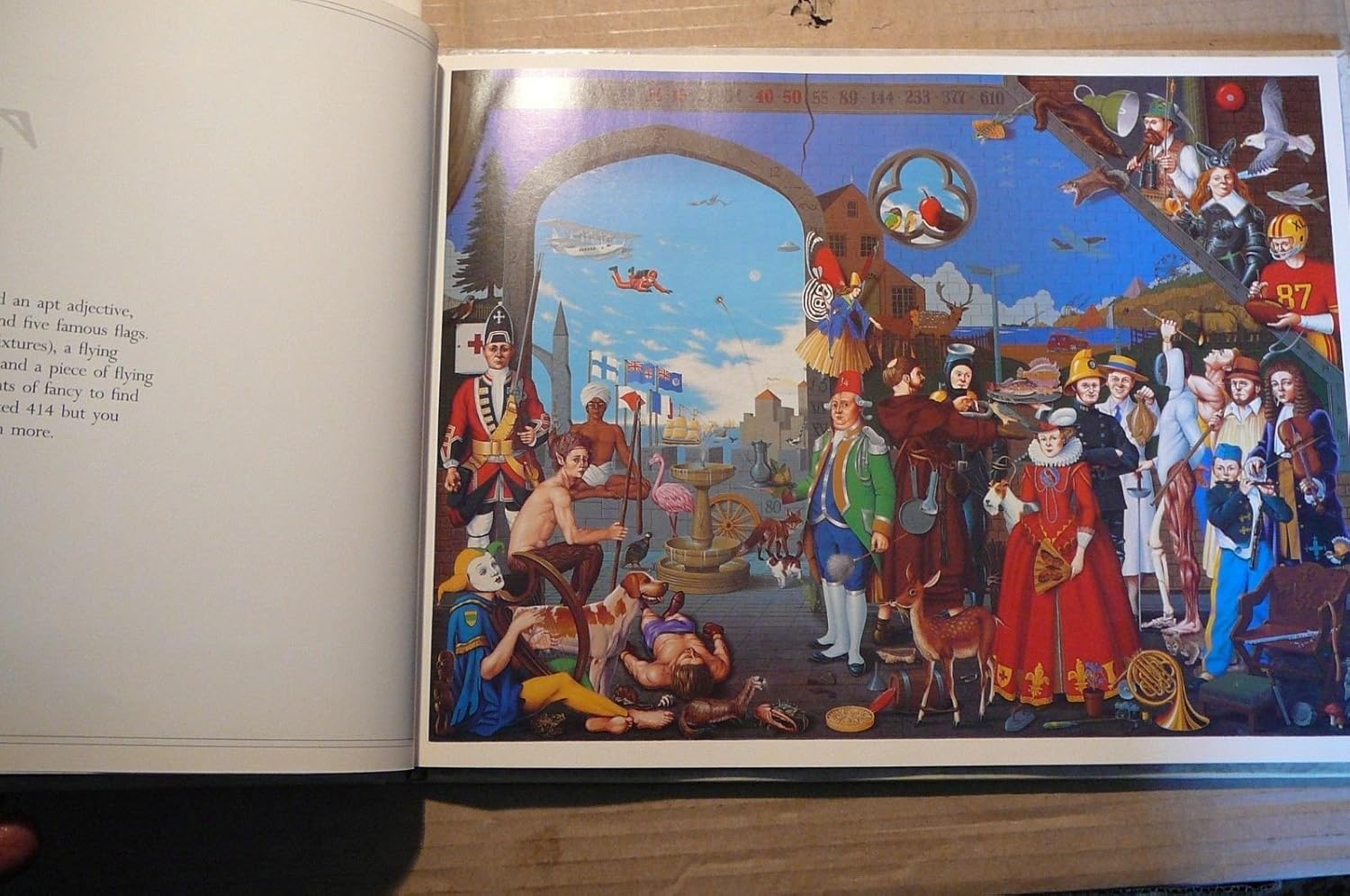

Look at that top image again. The picture book in it is an old favorite — The Ultimate Alphabet Book by the artist Mike Wilks, first published on Jan 1st, 1986.

I bought that book from Costco (where else) nearly 40 years ago. I have spent hours having fun naming the thousands of animals and objects hand painted in the book. A’s daughter D enjoys the book.

That picture of wine and bread brings me to the song that I want you to listen to: Leonard Cohen’s “Master Song.”

Here’s the first verse (and also the last verse) of the song.

I believe that you heard your master sing

When I was sick in bed

I suppose that he told you everything

That I keep locked away in my head

Your master took you travelling

Well, at least that’s what you said

And now, do you come back to bring

Your prisoner wine and bread?

And later in the song he writes —

I loved your master perfectly

I taught him all that he knew

He was starving in some deep mystery

Like a man who is sure what is true

And I sent you to him with my guarantee

I could teach him something new

And I taught him how he would long for me

No matter what he said, no matter what you’d do

I hope you get yourself a glass of red, turn down the lights, put your phone on silent, and listen to the song a few times.

The entire song is open to the listener’s interpretation. That’s the magic of Cohen’s poetry. About him, grokipedia.com says —

Leonard Cohen (1934 – 2016) was a Canadian poet, singer-songwriter, and novelist whose work spanned themes of love, loss, spirituality, and human frailty. Born in Montreal to a Jewish family, Cohen initially established himself in literary circles before transitioning to music in the 1960s. His introspective lyrics and gravelly baritone voice influenced generations of artists across folk, rock, and pop genres.

Cohen was a complex person, as creative people often are. He was ordained as a Zen Buddhist monk for a while. Here’s a bit from a qz.com July 2022 article, Leonard Cohen’s tortured love affair with Zen Buddhism.

For three decades, the Jewish poet pop star studied Zen Buddhism. At 65, he finally saw small miracles.

“There was just a certain sweetness to daily life that began asserting itself,” Cohen told The Guardian in 2001. “I remember sitting in the corner of my kitchen, which has a window overlooking the street. I saw the sunlight that shines on the chrome fenders of the cars, and thought, ‘Gee, that’s pretty.’”

After a lifetime of sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll, the smoking poet leaned into this epiphany. In 1994, Cohen retired to the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in Los Angeles, California and was ordained as a monk in 1996.

I love Cohen’s songs. The first time I heard a song written by him was when I was in college. The song was Suzanne from his 1967 album “Songs of Leonard Cohen.” But the Suzanne I heard then was sung by Neil Diamond. At that time I did not even know who Cohen was. I assumed that ND had written that song. Later I got to know and love Cohen’s genius.

Let’s listen to Neil Diamond sing that song.

The word burgundy (the wine-growing region of France) reminds me of another song. For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her by the always delightful Simon & Garfunkel.

Pressed in organdy

Clothed in crinoline

Of smoky Burgundy

Past the shop displays

I heard cathedral bells

Tripping down the alley ways

As I walked on

To wrap up this set of songs, let’s listen to Cohen’s “Take This Waltz.”

The words, oh the words. They are exquisite. And so is the music arrangement. I particularly love the female voice ornamenting Cohen’s voice. A commenter @QualeQualeson on the YouTube video wrote, “Always loved this tune and these lyrics. But for all my adoration, I simply cannot WAIT until Jennifer Warnes comes in with that second harmony. Sweet Jesus . . . a voice to die for. Recommend listening to her lead in Hair in 69, she would be around 22 at the time. That’s one minute you won’t be sorry spending on listening to vocals. God given talent.”

Listen to that bit from the song at 4:02 time stamp:

And I’ll dance with you in Vienna

I’ll be wearing a river’s disguise

The hyacinth wild on my shoulder

My mouth on the dew of your thighs

And I’ll bury my soul in a scrapbook

With the photographs there, and the moss

And I’ll yield to the flood of your beauty

My cheap violin and my cross

And you’ll carry me down on your dancing

To the pools that you lift on your wrist

Oh my love, oh my love

Take this waltz, take this waltz

It’s yours now, it’s all that there is

Full lyrics are there in the description to the video.

That’s it for now. Leave a comment if you have anything to ask or share.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.

]]>