Click the link to read the article on the Aspen Journalism website (Heather Sackett):

January 23, 2026

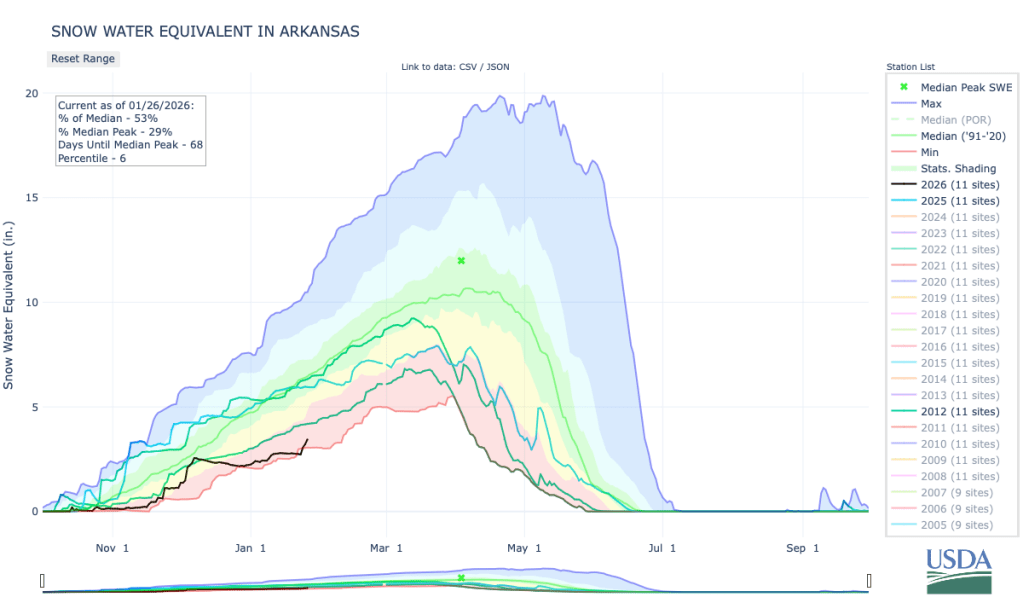

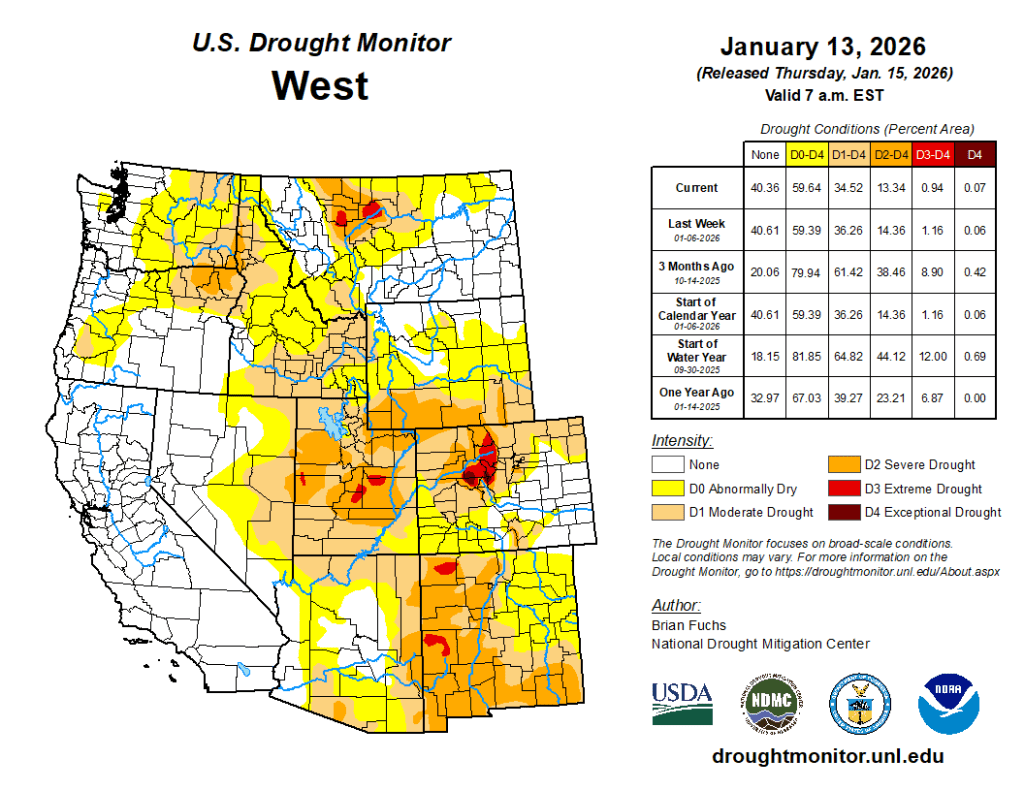

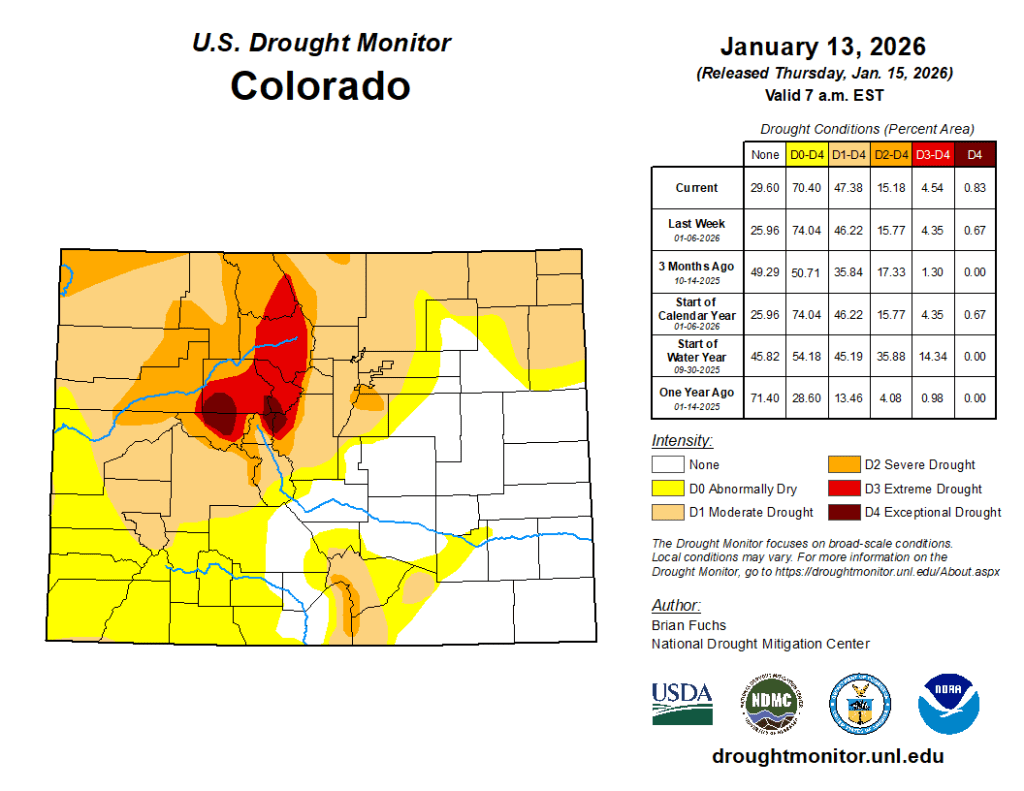

Pitkin County is making a historic deal to buy water currently used on the Front Range and put it back into the Roaring Fork.

The county plans to buy 60 shares of water from Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Co. and 34 shares from Fountain Mutual Ditch Co. For $6.5 million, Pitkin County will acquire about 71 acre-feet, although only 45 of those acre-feet represent Western Slope water that is currently diverted to the Front Range.

Pitkin County Commissioner Francie Jacober made the announcement at Wednesday’s board meeting of the Colorado River Water Conservation District.

“This is obviously going to help with the flows in the upper Roaring Fork,” Jacober said at the meeting. “It’s really exciting.”

The money for the purchase will ultimately come from the Pitkin County Healthy Rivers fund, which is supported by a 0.1% countywide sales tax. However, a portion of the funds for the purchase will initially come from the general fund, and the county will issue bonds before the end of the year that will be repaid using Healthy Rivers revenues.

According to a purchase and sale agreement related to the transaction that was posted online Friday, the Twin Lakes shares are being sold by Castle Concrete Co., while the Fountain shares are owned by Riverbend Industries, which is Castle Concrete’s parent company. Historically, the water involved has been used in the operation of a gravel pit and for gravel processing.

A memo outlining the deal noted that in order to purchase the Twin Lakes shares, the seller also required the county to buy the Fountain shares, which are estimated to yield about 26 acre-feet per year, but that water is not decreed for use on the west side of the Continental Divide.

“We are exploring options for disposing of these shares, either by trading for additional Twin Lakes shares or through sale, thereby offsetting a portion of the purchase price for the Twin Lakes shares,” the memo says.

Jacober told Aspen Journalism that the county worked with brokers West Water Research on the deal, which is set to close on April 2. Representatives from the company declined to comment on the pending transaction.

The Healthy Rivers board approved the expenditure in a 6-1 vote Jan. 15, and the Board of County Commissioners are set to consider the deal at the Jan. 28 regular meeting.

“I think the [Healthy Rivers] board is moved by the fact that water is really scarce in Colorado and there are not that many opportunities to own and control the timing of water, and that’s what we are excited about here,” said Healthy Rivers chair Kirstin Neff.

Pitkin County Deputy Attorney Anne Marie McPhee said the county heard that the shares were going to become available before they officially hit the market and officials approached the seller with an offer.

“That’s how we were able to get the shares,” McPhee said. “Because it’s very rare for these type of shares to come on the open market and usually the municipalities on the eastern slope are trying to get them as quickly as they can.”

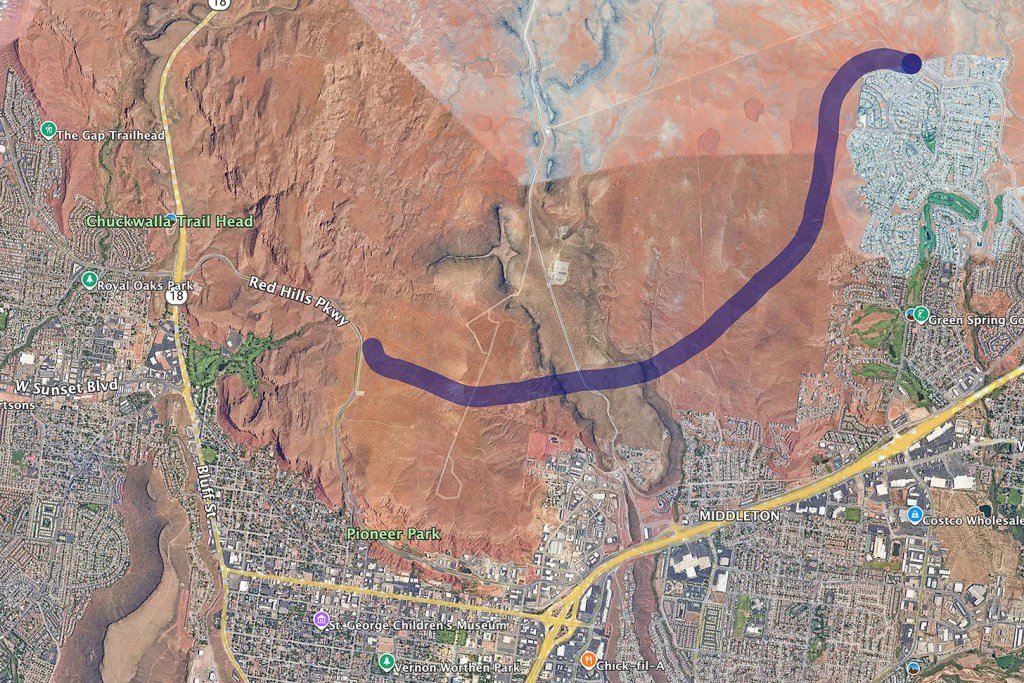

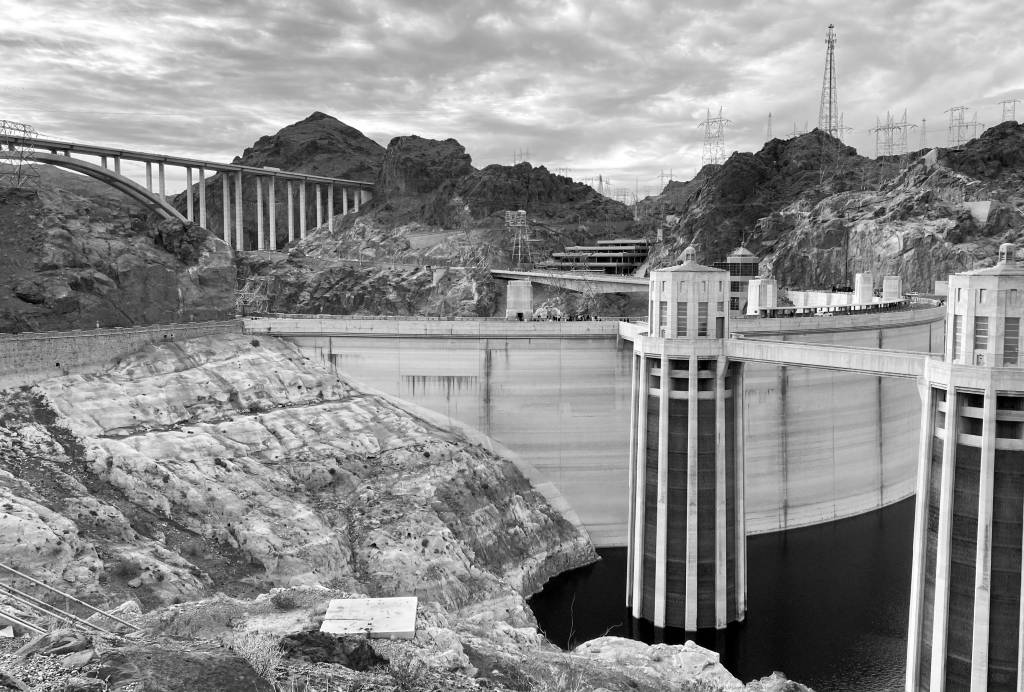

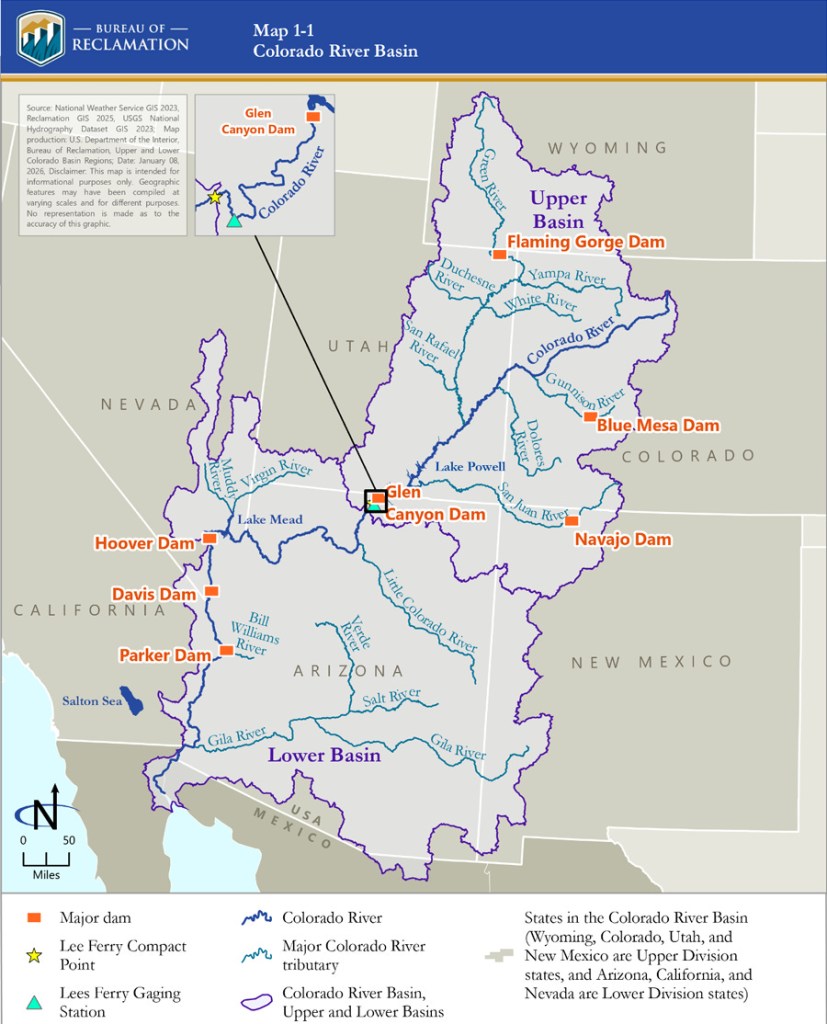

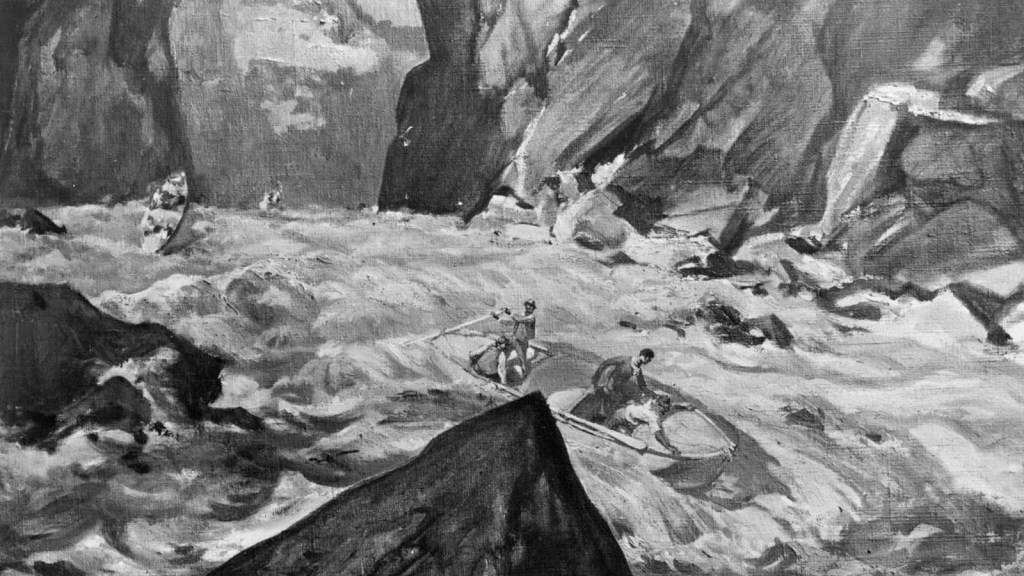

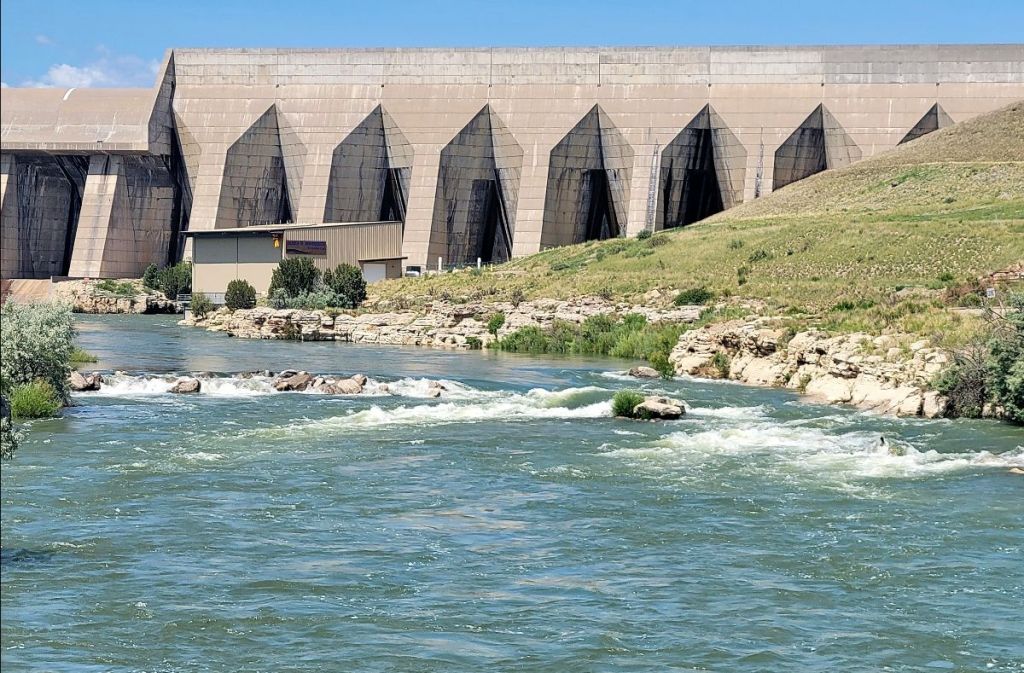

Twin Lakes system

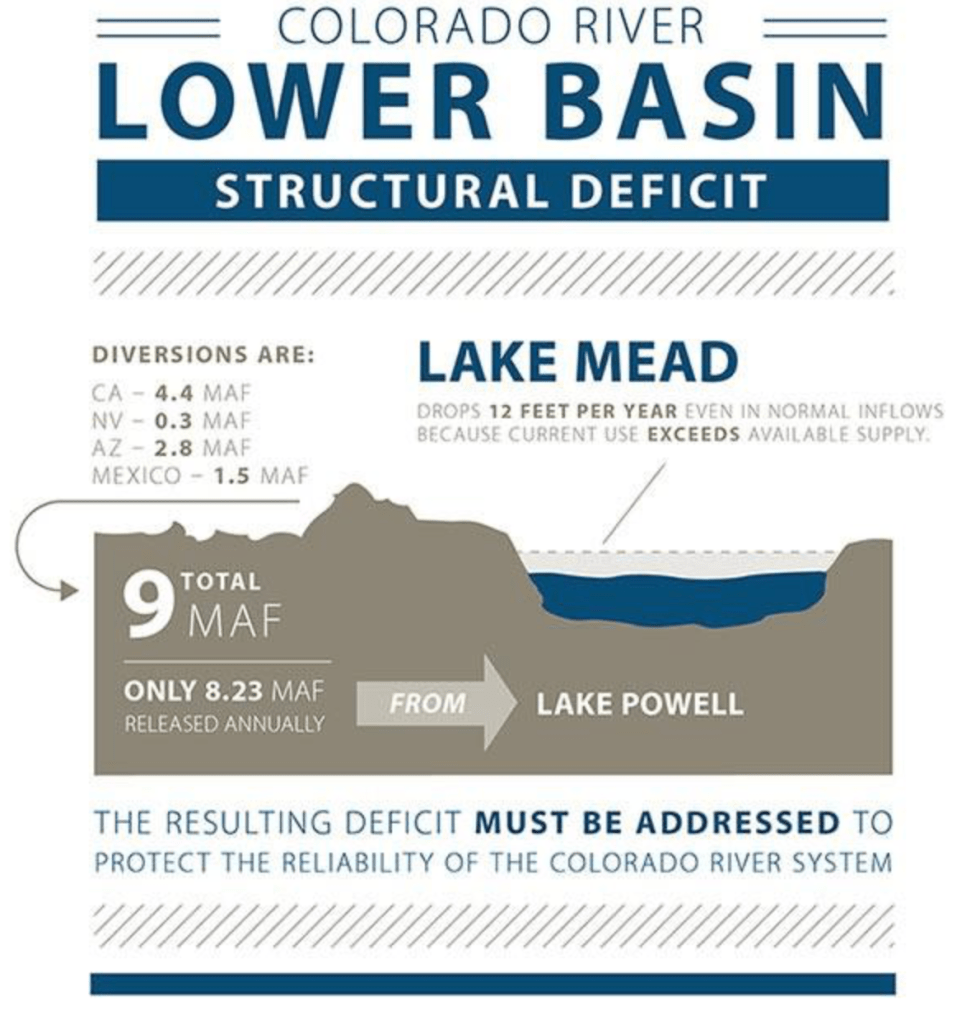

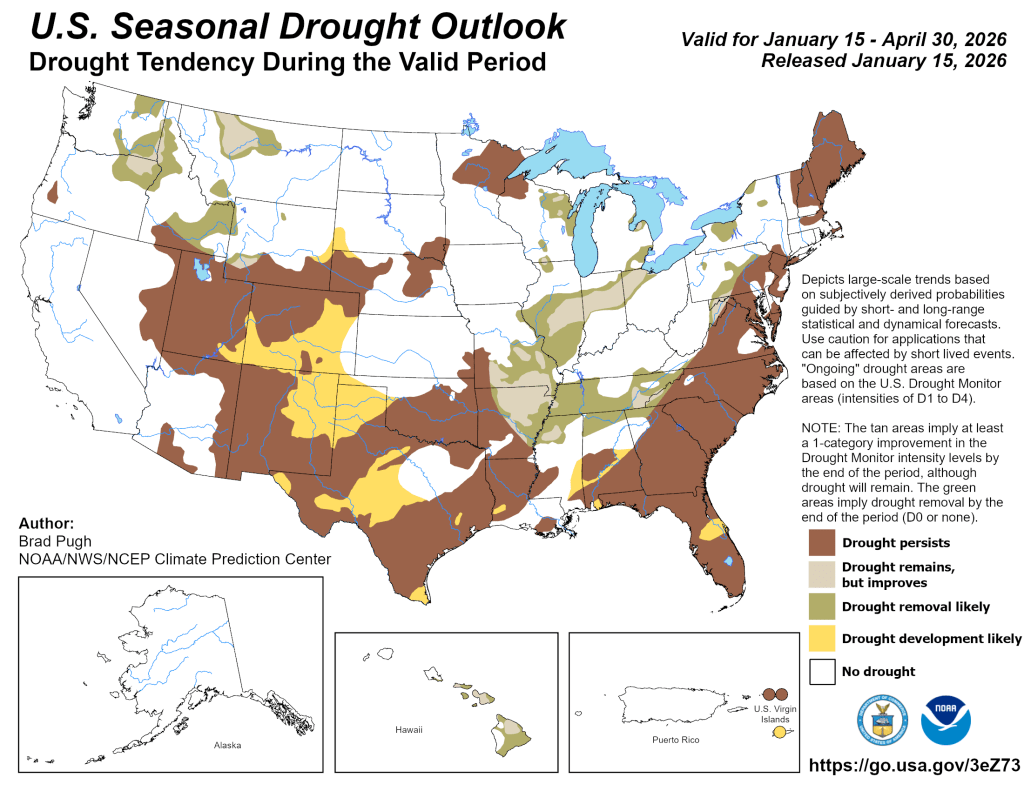

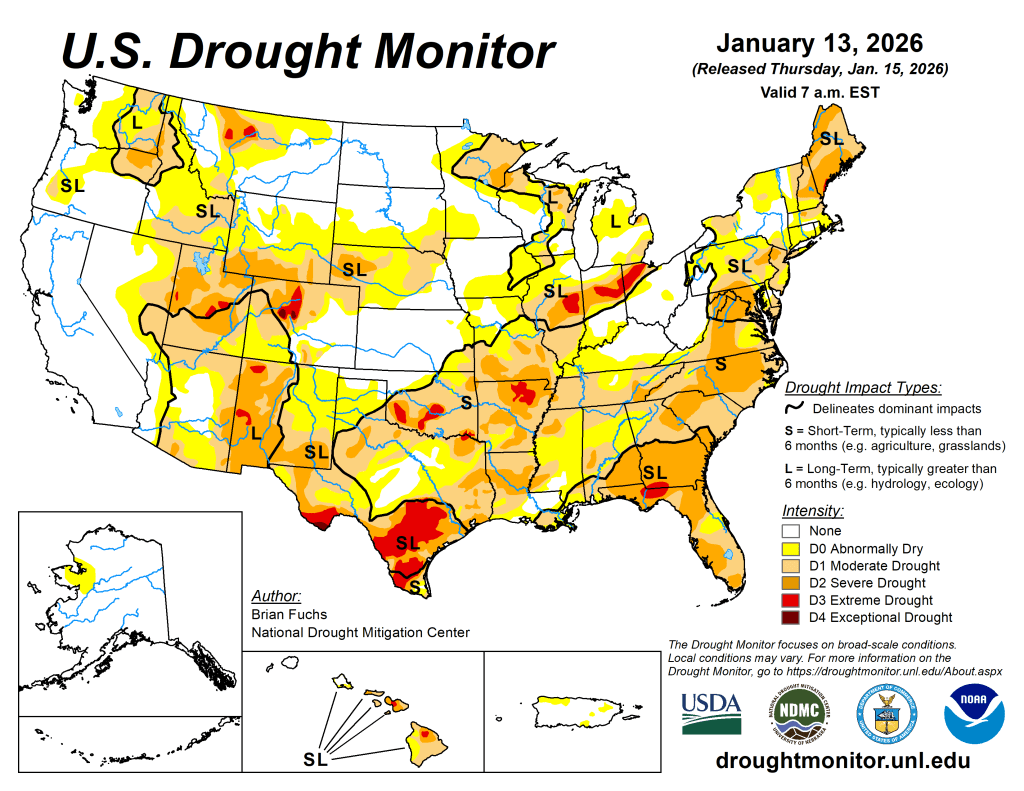

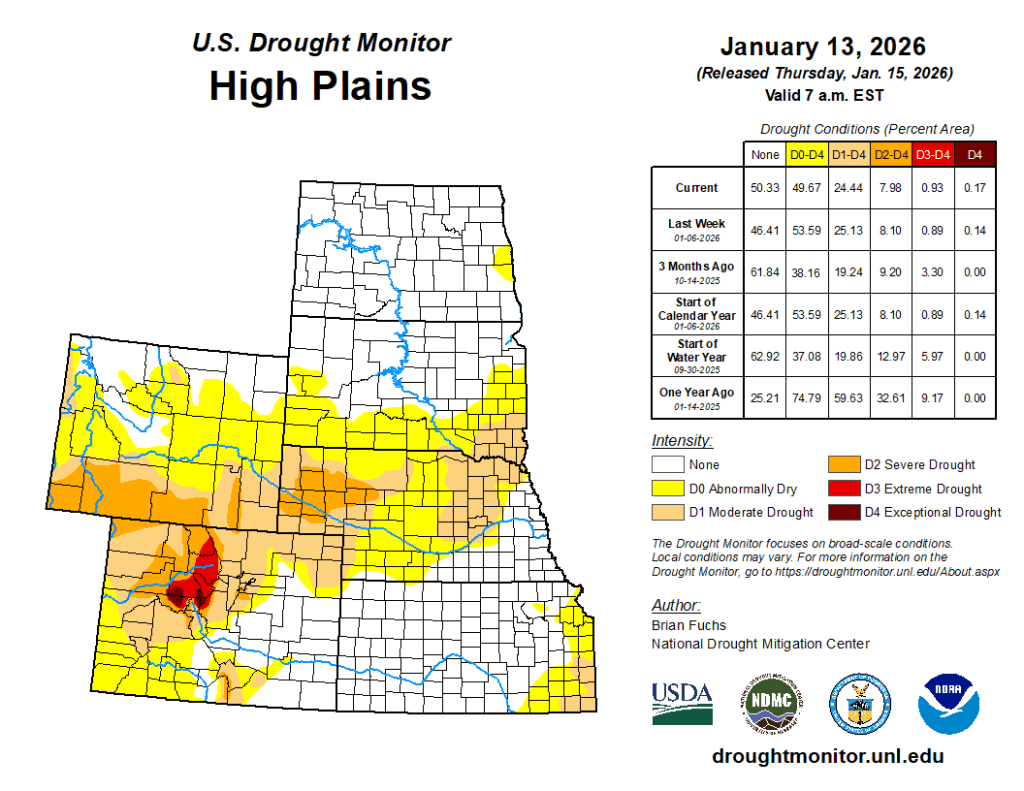

The Twin Lakes system is a complex and highly engineered arrangement of reservoirs, tunnels and canals that takes water from the headwaters of the Roaring Fork near Independence Pass and delivers it to Front Range cities in what is known as a transmountain diversion. Across the state’s headwaters, transmountain diversions take about 500,000 acre-feet per year from the Colorado River basin to the Front Range.

Four municipalities own 95% of the shares of Twin Lakes water: Colorado Springs Utilities owns 55%; the Board of Water Works of Pueblo has 23%; Pueblo West Metropolitan District owns 12%; and the city of Aurora has 5%.

The project is able to divert up to 46,000 acre-feet annually, or nearly 40% of the flows in the Roaring Fork headwaters, which can leave the Roaring Fork through Aspen depleted. Pitkin County’s purchase will return a small amount of that water to the Roaring Fork.

Pitkin County has long had a goal of boosting flows in the Roaring Fork, securing a recreational in-channel diversion water right for a park in Basalt and enacting exchange deals and other agreements with Front Range water providers that keep more water flowing west.

Twin Lakes President Alan Ward said the company is not directly involved in transactions between buyers and sellers of water shares. Twin Lakes must simply approve the transfer of certificates between the two.

County officials said they plan to release the water down the Roaring Fork during the irrigation season when flows are low, but not when the Cameo call is on, which already results in additional water in the Roaring Fork.

When irrigators in the Grand Valley place the Cameo call, which happens most summers, those with upstream junior water rights, such as Twin Lakes, have to stop diverting so that irrigators can get their share. When Twin Lakes shuts off, it boosts flows in the Roaring Fork.

McPhee said that although the deal is not cheap, it is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“You don’t get these opportunities to put physical water in the river anymore, particularly up at the headwaters,” she said. “So we are excited about this.”

Aspen Journalism is supported by a grant from the Pitkin County Healthy Community Fund.