| CARVIEW |

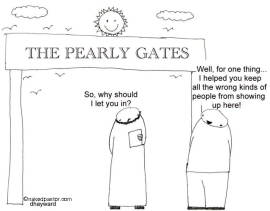

It is all too common to hear Protestant-minded Christians contrast the New Testament with the Old on the grounds that now God lives with us—directly—while in the old days people had to go to God through priests and other intermediaries. It is not difficult to find biblical support for such a notion, as Hebrews especially contrasts the old covenant with the new on the grounds that “Jesus the mediator of a new covenant” speaks and acts directly on our behalf (Heb 12:24; cf. 12:14-29; 9:11-10:25). But for all the influence such passages have had, they risk obscuring the fact that across scripture, not only in the Old Testament but also in the New, God most often chooses to speak and act through others.

Acts 10 is a case-study in indirection. This story of how a Roman Centurion named Cornelius came to accept the gospel serves as a paradigm for the inclusion of the Gentiles into the people of God. The curious thing about the story, however, is how indirect God is about bringing Cornelius to faith. When we first meet him, he and all his family are already “devout and God-fearing,” characterized by generosity and prayer (10:2; all quotations from the NIV). But however good and pious Cornelius is, God is apparently not satisfied to leave him there. Cornelius has a vision, in which an angel appears and praises his piety: “Your prayers and gifts to the poor have come up as a memorial offering before God” (10:4). God is pleased with Cornelius’ faithfulness, but God responds by sending a messenger, an angel, to speak for him.

And even the angel does not actually reveal anything to Cornelius directly—instead he tells Cornelius to “send men to Joppa to bring back a man named Simon who is called Peter” (10:5). Meanwhile, Peter himself is also praying when he too has a vision, in which “a voice” directs him to kill and eat an unclean animal, something forbidden to him as a Jew (10:9-16). Is this the voice of God himself, or another angel? We are not told, but after awaking from the dream, Peter then hears from “the Spirit,” who instructs him to go with the men who have come from Cornelius (10:19-20).

Obeying, Peter follows these men to Cornelius’ house and tells him about his vision, while Cornelius retells his own. Peter then replies with a long speech that is all about how God acts through others:

“I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism, but accepts men from every nation who fear him and do what is right. You know the message God sent to the people of Israel, telling the good news of peace through Jesus Christ, who is Lord of all. You know what happened throughout Judea, beginning in Galilee after the baptism that John preaches—how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and power, and how he went around doing good and healing all who were under the power of the devil, because God was with him.

“We are witnesses of everything he did in the country of the Jews and in Jerusalem. They killed him by hanging him on a tree, but God raised him from the dead on the third day and caused him to be seen. He was not seen by all the people, but by witnesses whom God had already chosen—by us who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead. He commanded us to preach to the people and to testify that he is the one whom God appointed as judge of the living and the dead. All the prophets testify about him that everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name.” (10:34-43)

Read that again and note all the different intermediaries God uses to speak to Cornelius. Though Jesus himself—his life and death and resurrection—stand at the center of everything here, God is claimed to speak and act through numerous others:

- The people of Israel, to whom God sent the message of “the good news of peace through Jesus Christ” (10:36),

- John the Baptist, who preached baptism before the coming of Christ (10:37),

- “All the prophets,” who testified on Christ’s behalf (10:43), and finally

- Peter himself and the other apostles, who saw the risen Christ and were commanded to preach (10:39-42).

In fact, Peter makes a point of stressing the limited nature of this final group of eye-witnesses: “He was not seen by all the people, but by witnesses whom God had already chosen” (10:41). In other words, while God in Christ could have revealed himself to all people directly, he chose not to do so. In Cornelius’ case, it is only when Peter came and spoke that he and his family—people already praised as God-fearing before they ever met Peter—are filled with the Spirit: “While Peter was still speaking these words, the Holy Spirit came on all who heard the message” (10:44). Only through Peter’s mediation does God finally make himself fully present to Cornelius, through the Holy Spirit.

For many, this is an uncomfortable idea. Isn’t the whole point of the incarnation that God is with us, directly and unmediated? Why should God go to all the trouble to take on human flesh, die and rise again on our behalf, only to fall right back to the same old indirect means of speaking and acting—through prophets, angels and human witnesses? Yet according to the author of Acts, that is exactly what God did. God did not speak to Cornelius directly; he first sent the people of Israel, who brought the words of the prophets. Then, even when Cornelius responded with faith and prayer and generosity, God still did not speak directly, but sent an angel. And even that angel did not reveal God’s word directly, except to send him to Peter. It wasn’t even that God sent Peter to Cornelius—though God did that as well—God made Cornelius take the first step by sending messengers to Peter, then made Peter follow the messengers back to Cornelius. Wouldn’t it have been easier if God had just appeared to Cornelius in person?

Why all this indirection?

After all, the author of Acts had just finished telling us about the conversion of Paul, who unlike Cornelius was met by the risen Christ directly, on the road to Damascus (Acts 9). Yet even there—even with the Apostle Paul—God insisted on using others, as Jesus appeared to Paul only in order to send him to Ananias, a man otherwise unknown to us (9:4-6). Jesus then also appears to Ananias, and directs him to go to Paul (still named Saul at that point), and it is only when Ananias obeys and goes and speaks to Saul that he too is “filled with the Holy Spirit” and baptized (9:17-18). The pattern is clear: Whether for an obscure Roman soldier or the Apostle Paul himself, God makes a point of using others to carry his message, and even requires those who would come to him—those who would be “filled with the Holy Spirit” and know God more intimately and directly—to first go to one of those who already knows God.

According to Acts, it doesn’t matter whether we are violent persecutors or generous God-fearers, God calls us through others, and sends us to others ourselves. These are the patterns Acts establishes at the founding of the church, and they are the paradigms that all of us have followed since: Every one of us who has come to Christ has done so thanks to the words and deeds of others. Every one of us who has been reached through others is called to reach out to others ourselves. There is no other way to God. Christ is the mediator, and we are the body of Christ.

So before we lament the indirection of God’s use of intermediaries—before we contrast those “old” ways with the “new” thing God has done in Christ—it is worth pausing to see what we gain from God’s choice to act indirectly. Instead of a bunch of isolated individuals, each provided a direct uplink to heaven, God has ensured that our faith is and must be defined by relationships, by mutual dependency, by community. If God had simply appeared to Cornelius directly and left it at that, Cornelius would never have had reason to reach out to Peter, and Peter would never have had reason to visit him. Cornelius, the Gentile, would have remained in the confines of his own family and context. Peter, the Jew, would have remained confined by the narrow view he sums up in 10:28-29,

“You are well aware that it is against our law for a Jew to associate with a Gentile or visit him. But God has shown me that I should not call any man impure or unclean. So when I was sent for, I went without raising any objection.”

It is only because God chose to act indirectly that the wall dividing Peter the Jew from Cornelius the Gentile was brought down, and a new possibility for community was opened up.

But even here we must be careful not to let what is new blind us to what was old, nor let us too strongly contrast “the law” with “the gospel.” This indirection, this insistence of God to act through others, was no new thing, and did not only become good with the coming of Christ. Peter’s words in 10:28-29 are too strong, and if taken in isolation they threaten to obscure Cornelius’ own history with God, which did not begin when Peter walked through his door.

Long before Cornelius ever met Peter, he had already met any number of those Jews Peter claims were forbidden to associate with Gentiles, and they apparently not only respected him, but associated with him enough to lead him to become a God-fearer in the first place (10:22). Not just the apostles, but all “the people of Israel” were sent by God the message of “the good news of peace through Jesus Christ” (10:36), joining in the larger pattern of intermediation stretching back to the prophets and continuing to the present, as Peter describes it. It was first and foremost through those others that God became known to Cornelius and his family, and after Peter left, it was these who remained as the context for his new life in Christ. The coming of Peter may have been the turning point in Cornelius’ relation to God, but it was neither the beginning nor the end of it. Both before and after this God was speaking and acting through others, indirectly but transformationally.

So it remains. Through Christ and the Holy Spirit, God makes himself directly available to people “from every nation” (10:34). But God has always done so through others—through us. The good news of the gospel is that God so much values human community that he even became human himself. The challenge of the gospel is that God so much values human community that he even sent us to carry his word for him. For through this indirect means, God calls us not just closer to him, but closer to our fellow human beings, no matter how different from us they may seem.

]]>

The so-called “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.” Image by Karen L. King. Click for full images and translation; posted by Harvard Divinity School.

As everyone knows by now, this past week Karen L. King, Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard, publicized the discovery of a small, purportedly 4th-century, Coptic manuscript in which Jesus refers to “my wife.” Besides contacting the New York Times, King also posted her academic paper (provisionally accepted for publication in Harvard Theological Review; PDF), along with a set of high-resolution photos, just before flying off to Rome to present her findings at the International Congress of Coptic Studies.

While the media, public and talk-show hosts have been speculating about what this means for modern debates concerning marriage, ordination and the latest bridal fashions (probably), scholars have been eagerly debating the authenticity of the manuscript itself. Bloggers James McGrath and Mark Goodacre have collected links to much of the discussion, including three brief articles by Francis Watson, a professor at Durham University. Watson argues that the manuscript was produced by copying texts from the Gospel of Thomas and other sources, perhaps even from a modern edition of the former. McGrath has expressed caution concerning Watson’s critique (and posted this humorous but instructive observation about the difficulty of telling coincidence from allusion), but at least some of Watson’s points appear to be valid, and the comments section of Goodacre’s posts include additional substantive observations. Other discussions–mostly critical–have spread across dozens of blogs, raising many points that will need to be addressed before this Coptic text could be accepted as authentic. Even the mainstream media has begun to acknowledge the issues raised in these debates.

Personally, I’m reserving judgment, but it is looking less and less likely that this is truly a fourth-century translation of a second-century document, as King claimed. As Richard Bauckham has suggested, even if Watson’s observations about the close parallels to the Coptic version of the Gospel of Thomas fall short of proving that this is a modern forgery (though that is a distinct possibility), they may well indicate that it was composed in Coptic originally, rather than being a translation from Greek. That would suggest, to me, one of two conclusions: Either it is a later Gnostic text first composed in the fourth century, or it is a sophisticated modern forgery by someone familiar with the Coptic language. At the very least, the shape and cut edges of the manuscript, and the maximum plausible length of the missing parts of the lines, all raise serious doubts about the nature of this text and its subsequent handling.

What is more interesting to me today, though, is what all of this reveals about the nature of scholarship in an age of round-the-clock news service and social media. Amidst so much press attention, it is a little disconcerting to hear that King’s paper met with extreme skepticism at the conference in Rome. Worse, yesterday it came to light that Harvard Theological Review is not committed to publishing King’s article after all, in light of the concerns already raised through their own internal review process (which King frankly acknowledged in the draft of her paper). The whole thing is starting to look rather embarrassing for Harvard, but more importantly, it indicates the danger of going to the press (or the internet) with one’s research before it has been fully vetted by one’s colleagues. “Accepted for publication” is not the same as published.

Now King’s article is not a bad piece of work. Though its conclusions are a bit overstated, to my mind, it is a well-researched and level-headed discussion that avoids the hyperbole that has swirled around it in the press. King has also been consistent in publicly rejecting speculations that this could “prove” that Jesus was actually married, emphasizing that at most it would show that the issue was discussed in the early church. Her academic treatment of the material may not be completely above reproach (questions here center mainly on the anonymous source of the manuscript), but its submission for peer-reviewed publication and presentation at the International Congress of Coptic Studies are entirely appropriate avenues for publicizing such a potentially ground-breaking discovery.

Beyond that, though, King’s publicizing of the manuscript raises real issues. Inviting the New York Times to publish such a discovery is not unusual, but allowing the Smithsonian to produce a documentary showcasing the “sensational” find before it has even been presented at an academic conference is hardly a mark of careful scholarship, regardless of whether this manuscript turns out to be authentic. The decision to post the draft of a peer-reviewed article online, before its appearance in the peer-reviewed journal itself, also seems problematic. King has won a great deal of attention for her work in this way, but she may dearly regret it if it turns out that she has been taken in by a fraud.

In this day and age, the media can be counted upon to broadcast such a story regardless of how it first comes to light, so the decision to hold a press-conference and at least try to limit the over-reaction is defensible. Nevertheless, the recent trend to go to the media first with such stories only deepens the public’s misconceptions about the nature of biblical and archeological research, giving everyone undue opportunity to celebrate the unmasking of traditional Christian belief, or the impiety of ivy league professors, as their taste may be.

In light of all that, it would be tempting to say that King’s going public in this way has done nothing but undermine the careful, reasoned debate that should be the mark of good scholarship. But the reality is much more complex and interesting, as the last week has demonstrated. By making both her paper and the high-resolution images of the manuscript public, King has also succeeded in facilitating an engaging and fruitful online discussion among her colleagues that would hardly have been possible before the rise of blogging and social media. Without the online publication of her work–premature as it may have been–the discussions that would have followed any leak to the media might have been much more superficial and speculative, and certainly would have been much less widely known.

To be sure, the fractured nature of online discussions (spread across the comment threads of a hundred blogs) can seem a poor medium for sustained academic discussion–and sometimes it is!–but the collaboration this enables has indeed quickly and effectively sketched out the major issues that will need to be addressed in relation to this discovery, as well as made some substantial progress towards evaluating them. Such debates can only occur to a limited extent at conferences, and would take months or even years to sort out through traditional publication, but it has happened in a matter of days online. It is only unfortunate that King herself–who has been traveling–has not been party to these discussions.

Given the speed of the media cycle, such a quick response from the scholarly community is indispensable. In the past, the publicized reactions to such announcements have too often been limited to knee-jerk responses from religious organizations, with a few skeptical but uninformed soundbites from established scholars, if we’re lucky. Substantive scholarly responses normally only came much later, long after the press has moved on to other news. Now such academic discussions can happen in real time, and have in this case directly impacted the media’s portrayals of the story–at least to a certain extent.

Additionally, all of this should help ensure that the peer-reviewed publications that do eventually follow will be better-focused than otherwise–though one wonders how, or if, they will explicitly credit these discussions for whatever insights the latter have provided. Blog-conversations are certainly no substitute for such scholarly publications, but neither are they irrelevant to them, and are essential in cases of “breaking news” like this. The days of dismissing blogging as an unimportant side-light are long over, and both its perils and potential for the advancement of research are here to stay.

]]>

Image by MorBCN, by Creative Commons license.

The Society of Biblical Literature International Meeting is less than a month away! For those who might be interested, my paper on Numbers 31 will be presented in one of the Pentateuch sections on Wednesday the 25th (Section 25-46). And if any fellow bloggers will be attending and would like to get together for a meal or whatever, I’ll be in Amsterdam from Saturday evening through Thursday morning. Here’s my abstract:

]]>Revenge and Redemption in Numbers 31

The slaughter of the Midianites in Numbers 31 has received surprisingly little attention outside of the commentaries, yet it is a fascinating text that takes up many earlier traditions in new and creative ways, with a literary sensitivity not often recognized. Picking up its story from Numbers 25 (in 31:2a and 16) and Numbers 20:1-13 (in 31:2b), it depends upon and in various ways adapts regulations found not only in the Priestly literature (esp. Exod 30:11-16; Num 19), but also in Deuteronomy (esp. 20:10-15), and elsewhere. Further strong literary connections are also to be seen with Joshua 22 and Judges 21:1-14.

Thus, Numbers 31 appears to be a late attempt to draw together diverse traditions concerning YHWH-war, as German scholarship especially has emphasized (e.g. Achenbach, Vollendung der Tora, Fistill, Israel und das Ostjordanland; Seebass, Numeri 22,2-36,13). How these traditions are reconciled and adapted, however, warrants further study. In particular, in will be argued that Numbers 31 not only attempts to coordinate YHWH-war traditions related to נקם and חרם with Priestly traditions of purification and the cult, it also uses a variety of literary means to contrast Moses’ command to slaughter the young boys and sexually active women in 31:14-18, with the כפר of “the officers” in 31:48-54. Both actions can be viewed as enactments of YHWH’s נקם and attempts to avert the “plague” (Num 31:16; cf. 25:7-9, 18; and Exod 30:12), but each offers a very different solution to that threat. In the end, it is not Moses’ call for slaughter that is afforded lasting significance, but the officers’ generous gift to the sanctuary.

Inching towards Deutsch. Photo from hexadecimal, by Creative Commons.

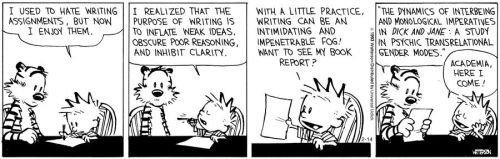

The problem with learning any new language is that it isn’t just one thing to learn; it is several quite distinct things that each must be mastered. You can have a perfect understanding of grammar but have to look up every other word in a dictionary. Or you can learn to speak fluently but not be able to read a sentence. Grammar, reading, writing, speaking, hearing–each is a distinct skill with plenty of overlap but not as much as one might expect. Each requires its own distinct strategies–and lots of practice–which can make learning a language very frustrating and time-consuming. I’ve studied eight languages now, and the only one I can claim to have mastered in all of these areas… is English.

Nevertheless, after living 20 months in Germany, including not only taking nine months of intensive German courses, but also studying two further languages in German (Ugaritic and now Latin), I’ve picked up a few things that might be worth passing on. With Joel beginning a new theological German study group this week, it seems a good time to look back on what I’ve found helpful so far, and what seems to work best for specific aspects of the language.

German Grammar

I began studying German privately about three years ago to prepare for doctoral work. At the time I did not expect to need to do anything but read it, so I picked up April Wilson’s German Quickly: A Grammar for Reading German and started working through it on my own. I’ve posted an initial review of this book before, and my opinion is largely the same now. Her grammatical explanations are generally clear and concise, her abundant use of German aphorisms makes the material more memorable, and her exercises are well thought-out. For English speakers who just need to read the language, it is probably the best place to start. But of course, the title is a misnomer–there’s no such thing as German quickly. As Mark Twain jokes in a brilliant article called “The Awful German Language” (ok, I think he’s joking…):

a gifted person ought to learn English (barring spelling and pronouncing) in thirty hours, French in thirty days, and German in thirty years.

Wilson’s book can “quickly” give you a foundation for reading German (how quickly depends entirely on how hard you are willing to work at it), but it won’t suffice on its own. For one thing, it just isn’t organized to be systematic, but rather to teach important points a little at a time. It is not a reference grammar, and even with the aid of its index it is only of limited help in answering specific grammatical questions.

The clearest systematic summary of basic to intermediate grammar I’ve found is Monika Reimann’s Essential Grammar of German: With Exercises (translated into English by Wolfgang Winkler). Strangely, only the German original appears to be available on Amazon.com, but you might be able to turn up a copy of the English version on Bookfinder.com. If not, the German version is itself intended for people just starting to learn German, so its charts and brief explanations should be comprehensible by the time you have gotten through an English introduction. It is sensibly laid out to make it easy to find specific topics, and it also includes abundant exercises to teach you to recognize and apply each of the topics it covers (a separate answer key is also available for sale). It is, however, just an introductory grammar, and lacks coverage of more advanced issues, such as verb-preposition connections and verb-noun connections.

For those and other (slightly) more advanced material, I’ve used an Übungsgrammatik für die Grundstufe (by Erhard Heilmann) and Übungsgrammatik für die Mittelstufe (by Friedrich Clamer, Erhard Heilmann and Helmut Röller). I found both very helpful despite being entirely in German (the hazards of taking intensive courses in Germany), but they are probably not to be recommended for self-study, and anyway they don’t appear to be easily available in the states. More likely to be useful to you are Martin Durrell’s Essential German Grammar and Schaum’s Outline of German Grammar, both of which I have used a bit and have been highly recommended to me by others.

Whichever grammar you use, one tip I can give is to spend some extra time at the beginning learning the article, pronoun and adjective declensions. Three genders, four cases and a range of seemingly inconsistent endings can make German nouns extremely difficult for the novice, but many German sentences simply cannot be understood without being able to distinguish various forms of the article (der, das, die, etc.), so internalizing those will make a huge difference in the speed and ease with which you can read, as well as the understandability of your speaking and your hope of following spoken German, should those be important to you. To that end, I adapted the following from various charts in Reimann’s Essential Grammar, which helps illustrate the patterns to the endings a bit better than a black-and-white arrangement shows (note that these are just the endings, not the full articles, pronouns, etc.; [Update: Image corrected; click to enlarge]):

Probably more irritating to an English speaker than the case system, however, is the German tendency to shove the verbs off to the end of the sentence. There’s a joke that German monographs have to be published in two volumes because the second one contains all the verbs. As Mark Twain again put it:

An average sentence, in a German newspaper, is a sublime and impressive curiosity; it occupies a quarter of a column; it contains all the ten parts of speech — not in regular order, but mixed; it is built mainly of compound words constructed by the writer on the spot, and not to be found in any dictionary — six or seven words compacted into one, without joint or seam — that is, without hyphens; it treats of fourteen or fifteen different subjects, each inclosed in a parenthesis of its own, with here and there extra parentheses which reinclose three or four of the minor parentheses, making pens within pens: finally, all the parentheses and reparentheses are massed together between a couple of king-parentheses, one of which is placed in the first line of the majestic sentence and the other in the middle of the last line of it —after which comes the VERB, and you find out for the first time what the man has been talking about; and after the verb — merely by way of ornament, as far as I can make out — the writer shovels in “haben sind gewesen gehabt haben geworden sein,” or words to that effect, and the monument is finished.

And yes, that was all one sentence. In three years, I’ve still not grown fully accustomed to German sentence structure, but one thing that really helped me was a simple observation one of my teachers made: Despite how it may appear, German sentence structure is not about pushing all the verbs to the end, but rather about creating a frame for the sentence. By splitting the verb in half and putting one half at the beginning and the other at the end (or in the case of subordinate clauses, the subject at the beginning and the verb at the end), Germans give a clear signal of where each thought-unit begins and ends. As my teacher put it: “Das Verb umarmt den Satz”, the verb embraces or enfolds the sentence. I don’t know if that makes it any easier to understand a monster German sentence, but it at least helps me not to get so annoyed by them.

Reading German

Reading is more than just grammar, however. You will also need a good dictionary or two and a lot of vocabulary practice. Wilson includes an appendix discussing German-English lexicons, which is a good place to start, though it is several years old now. I currently own seven German dictionaries, plus three or four little phrasebooks, and I’ve yet to find one that does everything I want. The Oxford German Dictionary and Collins German Unabridged Dictionary are relatively comprehensive (there is no such thing as a truly comprehensive German dictionary, since as Twain noted above, Germans can make up new words whenever they want just by sticking old ones together), but they are much too big to carry around and flip through on a regular basis. For a more convenient option–not to mention free–there are also some excellent online lexicons available. My favorite is dict.cc, which also allows you to download and use the database offline.

Personally, however, I find the process of looking up a word in a paper dictionary itself an important part of learning vocabulary (typing it in just doesn’t have the same effect), and it can also be helpful to highlight directly in the dictionary those terms you tend to look up the most often. This not only makes them easier to find later, but if you use distinct colors (for instance, for the different genders of nouns), it also makes the terms more memorable. Since remembering which gender each noun is seems to be one of the hardest things for English-speaking learners (this still gives me headaches!), anything you can do to help on that point is well worth it.

Thus when I am reading I prefer to have a small soft-cover lexicon within reach, and the best I’ve found so far is Langensheidt’s Taschenwörterbuch Deutsch-Englisch, which includes more terms than many desktop lexicons despite fitting in your pocket. It is easy to flip through with one hand even while holding a thick German novel in your other, and rarely lacks the word I’m seeking. Unfortunately, it was designed for German speakers rather than English, so it saves space by omitting plural noun endings and irregular verb forms. Thus it really needs to be supplemented with a list of irregular verbs (I just taped one into the front cover), and requires you to be able to recognize plural endings on your own, which will be much easier if you have taken the time to learn the article declensions.

If you don’t want to have to look up every other word, though, you’ll also need to start practicing vocabulary. Wilson’s German Quickly, like many other introductions, includes general vocabulary lists to get you started, and there are some good websites and programs available to help you. Wilson’s lists can be found on FlashcardExchange, which will save you a lot of data entry. If you are willing to put in a bit more effort, Anki is a nice little program available for free download (or as an overpriced app) that lets you create dynamic flashcards with color, images, recordings and even videos (if you are so inclined).

Whether you use one of those programs or plain old pen and paper, I’ve found that color-coding your vocabulary helps with memorizing, especially the gender of nouns. Adding a memorable image, sentence or quote to each flashcard can also be a great help. The key is not to pick something mundane–the more outrageous the image or sentence, the more likely you are to remember it. The trouble of course, is creating such flashcards takes a lot of time, and I must admit that I only managed to do it for a couple hundred terms. And then, of course, you have to actually use them to practice. Especially important is to memorize the gender of each noun as you learn it, as it is extremely hard to retrain yourself later if you ignore this aspect of the language up front. I speak from experience on this.

Most of all, however, both vocabulary acquisition and reading comprehension simply take–drumroll, please–actually reading! There is no substitute for reading as much German as you can, in as many different genres as you can. Narratives are always easier to read than journal articles and the like, so start with children’s books and a contemporary German Bible (as in English, there are many German versions, some easier to read than others). Another great option is to find a German translation of one of your favorite books, as knowing the story in advance makes it much easier to follow along even if you don’t understand every word. Regardless, it will be slow going at first, but you’ll pick up speed quickly if you keep at it.

For example, early on I picked up a German translation of the Harry Potter books at a flee market here. It took me a good week to get through the first chapter of the first book, but only two months to finish Der Stein der Weisheit, one month to finish the second book, and two weeks to finish the third. Admittedly, I was taking intensive German courses at the same time, but the basic vocabulary repeats so often in a novel that it really does make a huge difference just reading as much of it as you can. A word to the wise, though: German narratives make ample use of the simple past tense (also called the preterite or imperfect, or in German Präteritum or Imperfekt) and the subjunctive (Kunjunktiv), which most introductions don’t teach right away. You’ll save yourself a lot of headaches if you familiarize yourself with those first, and again you’ll want a list of irregular verbs close at hand (for instance, here is a PDF).

Being able to breeze through a familiar narrative, however, is much easier than getting through an academic text, so you will also need to practice reading as much of those as possible as well. Introductory textbooks will of course include their own texts at a basic and intermediate level, and a German Bible can also offer good practice in a variety of genres as well as building your theological vocabulary. On that score, a number of people have recommended Helmut Ziefle’s Modern Theological German, which includes a set of texts drawn from the German Bible and a number of classic German theologians, bound together with a German lexicon. Unfortunately, I found the book disappointing. The practice-texts are helpfully arranged in increasing order of difficulty, but thin on explanation, and the exercises are not overly helpful. That new terms are defined directly opposite the text makes translation much easier (perhaps too easy), but the dictionary itself is almost worthless. I’ve yet to find a single term in it that was lacking from my general-purpose dictionary, and even its theologically-oriented definitions are rarely more helpful than their general-purpose counterparts, while its 20,000 entries are simply not sufficient for reading complicated texts. It’s a shame too, as given how many German terms have become standard even in English scholarship (think of Sitz im Leben or Heilsgeschichte) a good dictionary of theological German would be very welcome indeed, if only someone would produce one.

Speaking and Listening

Finally, for those who would like to actually use and understand spoken German–or at least gain a better idea of how the German alphabet is actually pronounced–I’m afraid no book alone will do. A decent place to start is with German versions of animated films such as those from Pixar. Since they are made for kids, the language is generally pretty simple, and the voice-overs are often just as natural as the originals (which is never the case with live-action movies, despite justifiable German pride in their dubbing ability). I would also highly recommend Pimsleur’s Speak and Read Essential German. Despite its title, Pimsleur will teach you precious little reading German, but it is still well worth using, both for getting a sense for German pronunciation and establishing some basic vocabulary and sentence structure. Its conversational method and use of timed reminders to cement new vocabulary and concepts in your memory offer a welcome break from flashcard-based methods, and it can be used very effectively while driving or doing other activities that preclude holding flashcards or a textbook. It is expensive to purchase, unfortunately, but many public libraries will have it available to check out.

Such is unfortunately not the case with RosettaStone, which is even more expensive (and has very harsh restrictions preventing installation on multiple computers, which is a problem if you have to reformat). Despite that, it is still a fraction of the cost of a German course at a university, and definitely worth the money if you can find no more formal method to practice speaking. It teaches vocabulary much faster than Pimsleur, in part because it uses images to increase retention, and it is much more pleasant to use than ordinary flashcards. My wife never took a single German course, but after completing two levels of RosettaStone and one level of Pimsleur, she had learned enough to converse in German. To this day she has hardly touched a grammar book, but after finishing all five levels of RosettaStone and simply getting out there and talking to people as much as she can, she probably speaks German better than I do at this point, simply because she has never let fear of making mistakes keep her from speaking. That said, her reading and writing German have not advanced nearly as far since neither Pimseleur nor RosettaStone are very effective at teaching those aspects of the language. RosettaStone is also built with Flash, of all things, so it is rather buggy considering how much it costs.

What is especially good about both Pimsleur and RosettaStone is that they teach you to speak German untranslated. That is, they can very quickly teach you to respond naturally in German without first having to translate into or out of English in your head. RosettaStone uses no English at all, relying solely on images to teach you the meaning of new words and constructions (which is the source of both its advantages and disadvantages, as it is not always clear what grammatical distinctions they are trying to teach you). Pimsleur, lacking the possibility of images, does provide an English translation for everything, along with some brief grammatical explanations, but it deliberately teaches you not to rely on such translations, and in fact replaces more and more of the English prompts with German ones as the course progresses.

Nevertheless, both Pimsleur and RosettaStone can lead you astray at times, either because they lack real grammatical explanations, or because they are simply inaccurate. For instance, I went around for the first two months here greeting people with Angenehm! because that was how Pimsleur taught me to say “Nice to meet you.” I found it odd that no one ever said it back to me, until one day I said it to the president of the university (!) and he replied “Nein.” Apparently, he did not recognize it as a greeting at all, and thought I was saying his job as president was “pleasant,” which he (playfully I hope!) denied. (For the record, the most standard way to say “It’s nice to meet you!” in these parts is: Freut mich, Sie/dich kennenzulernen!)

The moral of the story is, if you really want to learn German, move to Germany, or at least find a good immersion class taught by a native speaker. At the very least, be sure to use both a good grammar book and something like Pimsleur or RosettaStone, as either one by itself can only teach you a small part of the German language. If you would like to do more though, check out your local community colleges to see if they offer German courses, or if you live near one of the Goethe institutes, they are supposed to be very good, though very expensive.

Better yet, come to Germany yourself. Here in Göttingen there is an excellent institute that offers six-week courses (150 class hours) for 400€ or less. There are also grant foundations that provide funding for study in Germany (e.g. Fulbright and DAAD), and indeed if you can find a way to meet the entrance requirements, tuition at a German university costs virtually nothing compared to an American one (the undergrads in Göttingen were protesting this year when tuition was raised to a whopping 717€ per semester! As a doctoral student with a stipend, I paid only 142€ this semester to attend one of the best universities in the world). A number of American universities also have their own exchange programs, and more established scholars should consider applying for a Humboldt grant.

But even if you are just looking for a good vacation spot, with a bit of German practice on the side, Germany is a beautiful country, with lovely old cities and castles and a fantastic train system. It is well worth a visit.

]]>

[UPDATE 6/2012: I am very pleased to report that the recent software update has resolved virtually all of the complaints noted below, making this an even better device than it already was.]

Having received a Kindle Touch for Christmas, I thought I’d offer a quick review and comparison with the Kindle 3 (now known as the Kindle Keyboard). I’ve also included a list of gestures near the end, since I’ve not been able to find one elsewhere.

My wife got a Kindle 3 over the summer and we both fell in love with it immediately. It is an extremely well-designed device that can make reading digital text virtually as easy and natural as reading on paper. I’m not one to spend a lot of money on ebooks–though Amazon does have an impressive library of them–so mostly we’ve used it for reading classics, which are generally free since they are out of copyright. Amazon has a number of them itself, and many more are available through Project Gutenberg. I’ve also used it here and there for academic reading, either of classic texts like Wellhausen’s Prolegomena, contemporary articles that are available as PDFs through the university library, or personal notes and documents.

Sometimes this works great, other times less so. For documents that are not already formatted for the Kindle (.mobi), you either have to load them unconverted, which limits their functionality, or use Amazon’s conversion service, which is great but not without problems. One need only email the document to them with “convert” in the subject line and it will be sent directly to your Kindle within a few minutes, but unfortunately it only really works effectively with Word documents and searchable PDFs that are exclusively in English, and it can’t handle Hebrew or other right to left scripts at all. Even German comes out a bit garbled when converted, and transliterated semitic languages are unreadable. In all cases, original formatting will tend to be lost or cause display issues. Unconverted PDFs can be loaded instead, which will preserve the original scripts, formatting and images, but such cannot then be searched or highlighted, and unless they are saved to a smaller page-size to begin with (as with many journal articles), they tend to be too small to view comfortably without scrolling.

The Kindle Touch shares most of these advantages and disadvantages with the Kindle 3, but it does have a couple of additional limitations. In particular, there is no landscape mode, and you cannot highlight across a page break. The first is the more irritating, as unconverted PDFs, as I said, often cannot be viewed comfortably as whole pages, and work better in landscape mode (half a page viewed at a time). It is unclear why they deleted this feature–perhaps it would have made the page-turn gesture recognition software more complicated?–but hopefully they will bring it back for future models, or preferably through a software update (unlikely?). As for highlighting across the page, there is a workaround: simply decrease the font side using the pinch gesture until the full quote is on one page, make your highlight, then restore the text to its usual size. [UPDATE: Both landscape mode and the ability to highlight across pages have now been added.]

Apart from those limitations, the Touch is in almost all other ways an improvement over the Keyboard version. Besides being smaller and lighter (it easily fits in my jeans pocket), while still keeping the same 6” screen size, the new burnished aluminum look is much more attractive, yet is still rubberized so as not to slip in the hands or feel cold. I can comfortably use it with one hand, including page-turning and for longer periods of time, though I find that I most often tend to use my other hand to turn the page.

In general, I find the touch interface much quicker and more natural for navigation and highlighting than the Kindle 3’s directional pad, not to mention saving a great deal of clicking. Simply being able to press and drag from the first word to the last is much easier, and adding a note is no more difficult with the on-screen keyboard than with the tiny little hardware keyboard on the Kindle 3, which I always found rather ugly. Granted those with big fingers will find either one difficult, but personally, I find I can type a bit faster with the on-screen keyboard. Neither model is conducive to extended note-taking, however. The only real downside of the Touch on this score, and it is not a small one, is that there does not appear to be any way to make corrections within a note except to delete everything that follows and retype it. Tapping at a point earlier in the note does not move the cursor, which seems a rather glaring omission from the software. At least with the Kindle 3 you could move the cursor with the directional pad. [UPDATE: This feature has now also been added. Three cheers for listening to customer feedback!]

The E-Ink display is noticeably clearer and brighter over against the Kindle 3, since the touch capability is provided by inferred scanners built into the bezel, rather than built into the screen itself. This also means that unlike an iPhone or iPad, it works without direct skin contact, so you can read with gloves on or even use the back of a pen or other pointer. The latter can be helpful if you have thick fingers, though the touch sensitivity does not appear to be quite as good with a pen as with my finger. The downside is that bumping the screen (e.g. with your sleeve) will be treated the same as your fingers would be.

In general, the touch capability is reasonably accurate, but not quite as good as I would have hoped. You really have to hit the on-screen buttons directly in the middle to activate them, and it does not always recognize my taps to turn the page, while other times I apparently have not held long enough to begin highlighting and instead accidentally turn the page. Presumably that will improve simply by getting more used to the device. There are also a small number of gestures built in, though for some reason Amazon does not (yet) appear to have any documentation for these. Trial and error and some help from Google has turned up the following (note that not all of these work with all kinds of documents, but with standard ebooks they normally do; if you know of any further gestures I’ve missed, please let me know!):

- Tap the Page moves forward one page

- Tap the Right Edge moves back one page

- Tap the Top Edge accesses Back, Search, Menu and Formatting Options

- Tap the Top Right Corner adds or removes a bookmark.

- Swipe Left moves forward one page

- Swipe Right moves back one page

- Swipe Up jumps to the next chapter (or section break)

- Swipe Down jumps to the previous chapter (or section break)

- Pinch Inwards reduces the font size one level

- Pinch Outwards increases the font size one level

- Press-and-Hold (2 seconds) accesses a pop-up dictionary definition with additional options

- Press (2 seconds) then Drag adds a highlight, then opens a pop-up dialogue with additional options. Close with a Tap.

The Swipe page turns are not really necessary when reading a book, since a simple tap accomplishes the same goal. I tend to do it anyway, though, as it feels more like turning a real page, and makes the refresh delay seem less unnatural to me. The Kindle also seems slightly more accurate at recognizing swipes than taps. On the Home Screen, where tapping a book title opens it (and press-and-hold accesses additional options), swiping appears to be the only means of turning the page. One issue I have had, and at first irritated me a great deal, is that occasionally a stray bump is interpreted as a Swipe Up, which jumps you to the next chapter. If this happens though, you can simply tap the top of the screen to access the menu, then click the Back button (looks like an arrow) to return to your previous position–much easier than trying to find your place by paging back repeatedly!

Accessing the menu does take an extra step compared to the Kindle 3, and also adds a bit of extra time for the additional page refresh. Indeed, the page refresh speed in general appears to be slightly slower with the Kindle Touch compared to the Kindle 3, and the Kindle 4 is quicker still, but most of the time I don’t even notice. Even the Home page takes a bit longer to load, despite there being a hardware button to access it (the four little lines on the front that look like a speaker), so as others have also noted, this is likely a software issue rather than a hardware problem, and might hopefully be improved by software updates. [UPDATE: This also seems to have been resolved, as I no longer detect any noticeable difference in load speed. If anything the Touch may be a bit quicker than our Kindle 3.]

I should also note that both our Kindle 3 and Kindle Touch were purchased with Wi-Fi and “Special Offers.” I have no need for the 3G and in any case prefer the convenience of emailing documents to my Kindle, which is free with the Wi-Fi version, but costs a nominal fee with the 3G version. As for the ads, I’ve been pleasantly surprised by how unobtrusive they are: They do not show up in reading mode at all; you only see them in sleep mode and as a small banner on the bottom of the Home page. Moreover, they sometimes even offer legitimately good deals, such as free ebooks and audiobooks, half-off coupons for Amazon itself, and similar things. That said, I have noticed that the number of these seems to have decreased lately, with more standard ads taking their place (e.g. currently they are cycling through a $15 off ad for jeans on Amazon, a $50 discount for Travelocity, and standard ads for T-Mobile and a Katherine Heigl movie). If the latter two type of ads come to replace more and more of the former two, I may become rather less happy with the Sponsored Offers version than I currently am, but if it really gets bad, I can always pay the difference for the non-ad version later.

All around, I’m very pleased with the Kindle Touch, and definitely prefer it to the Kindle 3, even if it still leaves room for improvement in future models. In particular, I would like to see a model that had a touch screen with a small number of hardware buttons for Home, Menu, Back, and Search (useful for dictionaries especially), as the latter three currently require an extra tap each. The one button design seems an unnecessary concession to the iPhone/iPad, and I see no reason to stick with it. On the other hand, though at first I thought I would miss the hardware Forward/Backward buttons, in practice they are unnecessary and would probably just get in the way.

]]>

Image by neoporcupine on Flickr, by Creative Commons License.

Like any American male, I’m genetically obligated to love driving. I grew up building race tracks for my Hot Wheels and drawing pictures of Porsches and Lamborghinis. My best friend had a gas-powered go-cart that we used to race around the neighborhood, pretending we were in the Indy 500. To a kid, a car is freedom–to go where you want, when you want, without parental supervision. To drive is to be an adult. Unfortunately that is only too true.

The first day I had my license, I caused an accident. I changed lanes on the freeway without double-checking my blind-spot and ran a guy off the road. The worst was that I didn’t even realize I’d done it, and continued on my merry way. After a while I noticed that some jerk was following me, and when I got to my destination he stopped right next to me and stared the whole time I was getting out of the car. I gave him a dirty look and walked away. That night, we got a call from the state patrol informing us of the accident, which the guy who followed us had apparently reported. Needless to say I felt like an idiot, and never again forgot to check my blind-spot.

Luckily the damage was minor, but the affair still cost us $300. Another accident a couple of years later seemed even less significant (I backed into a parked car) but ended up costing a lot more because it just so happened to catch the driver-side door at the wrong angle. A $1000 deductible and 3 years of higher insurance premiums for what looked like a little ding. I haven’t been in an accident since high school, but owning a car never gotten any cheaper. Loan payments, insurance, regular oil and filter changes, maintenance and repairs and gas, gas and more gas add up to an incredibly costly investment.

I’ve owned four cars, which were purchased for $6000, $1000 (from a family member), $11,000 (plus $3000 interest) and $5500 (plus $800 interest). I ran the first one into the ground, prematurely, as I did not realize the problem was fixable until it no longer was. The second was traded 6 years later for $800. The third I sold for $2000 (that was some serious depreciation!), and the fourth I also sold for $2000. That’s over $20,000 in sunk costs, not to mention hundreds of dollars a year for insurance, thousands of dollars a year in gas, and who knows how much more for repairs, major and minor.

Today I own no cars, three adult bikes, three children’s bikes, a bike-trailer and a Laufrad. All-told they cost somewhat less than 500€, require no gas or insurance beyond my normal personal liability insurance (pretty much necessary in Germany), and I can repair almost anything that goes wrong with them myself. If the worst came to the very worst, I could replace any one of them for under 200€. If I had to do that every other month all year, it would cost me less than I was paying in insurance for my cars in the US.

Last night I spent two hours fixing a flat tire on my bike, re-aligning my daughter’s chain, and adding a new coupling for the bike-trailer to my wife’s bike. It was the most effort I’ve had to spend on the bikes at one time all year, and it cost me 11€ for the coupling and a 10-cent patch. Later this week I might replace my rear brake-pads. That will set me back another 5€ and about 20 minutes. I don’t even want to think about what a blown tire, a drive-shaft problem, a new trailer hitch and new brakes would have cost on a car, even if I could fix them myself, but I’m fairly certain it would be just a bit more than 16€.

Living in Göttingen, I go almost everywhere by bike. I have a basket that suffices for a small bag or a few items, and if I need to move something bigger, I can use the bike trailer. If we need to go somewhere too far for the kids to bike themselves, they also can ride in the trailer (which is what it is actually designed for). We even have a kid’s seat on my wife’s bike that can be used in good weather. Two or three times a month we might take a bus instead, especially if our destination is up a steep hill or the weather is really nasty, and a couple times a year we may have reason to rent a car for a longer trip, though we usually just take the train. That goes everywhere, is comfortable and convenient, and isn’t necessarily expensive if you buy your tickets in advance or take the slower trains.

When I think of all the years I insisted on climbing into my car to drive 2 minutes down the road in the states, it seems absurd. Who on earth decided that it was a good idea to power 2000 lbs. of metal, glass and plastic by burning an expensive and highly explosive liquid, when a 20 pound bicycle powered by your own two legs could get you there just as quickly?

To state the obvious: A bike requires virtually no natural resources to use, produces no pollution, gives great exercise, and costs pennies on the dollar to maintain. On a sunny day it is better than a convertible, and far more peaceful. It is fully customizable and just about anyone can learn to repair one. When was the last time you tried to replace anything more complicated than a lightbulb on your car? I don’t even know what half the things under the hood do, much less how to fix them, while even my five year old can understand how a bike works. Yet despite all these advantages, few Americans even consider using a bike as a regular means of transportation, much less an exclusive one. For most of us (myself included before this year), biking is a form of recreation, nothing more.

To be sure, shopping and other errands require better planning on a bike, but that’s a small sacrifice. There are also risks involved–if a car hits a bike, the bike loses, every time–but I’m not convinced that biking is any less safe than driving in general, particularly in a city with good bike paths. A more common problem is weather, though with proper clothing that is not as big of an issue as one might expect. Heavy snow can sometimes make biking impossible, but personally I’d rather bike in the snow than in the rain, especially when the temperature is in the mid-30s–like today. Often the best you can do then is wait it out, as even wet days are rarely consistently rainy.

A bigger headache is broken glass. Bike tires are a lot more fragile than steel-belted radials, and people around here seem to have a bad habit of breaking beer bottles right in the middle of the bike lanes. It happens so often, I’ve begun to suspect it’s intentional. It’s rare if I can go a week before finding a new patch of broken shards somewhere along my usual route to work, and it is not always easy to see them quick enough to avoid them. Even so, the city has enough street-sweepers to do a reasonably good job of clearing such things up, and my flat tire this week was surprisingly the first I’ve had on this bike, and only the fourth I’ve had to fix all year.

Of course, if you’d rather not face the weather and the beer-bottle mine-fields, you can always ride the bus. It would take a lot of 2€ bus fare to add up to the cheapest used car, and even a monthly pass will be a fraction of the typical car payment. Sure, buses are less convenient than your own sedan, but they certainly beat sitting in traffic. That I once to looked down on people who took the bus just seems silly now. Why drive when I can sit and read while someone else takes me where I need to go? And if I do want to get there faster, even a car is no quicker than a bike over short trips, since a biker doesn’t have to stick to the roads or find a parking place. All told, I could probably count on one hand the number of times I’ve actually wished I had a car in the last year.

Granted, there are probably few better places in the world to live without a vehicle than in Göttingen. It is a medium-sized city in a mostly flat valley, with moderate weather and a compact city-center. Besides the excellent transit system, there are bike paths on almost every street and most other places as well. Many stores have more bike-stands than parking spots, and drivers are well-accustomed to watching out for riders. Much of the downtown area is closed to traffic entirely, and it is amazing how that one rule can make a city of 100,000 feel more like a small town, without eliminating the conveniences of living in a city. It is almost impossible to go downtown without running into someone you know, simply because everyone is walking rather than racing past each other in their cars. Seeing a friend means you can actually have a conversation, not just a honk and a wave.

Unfortunately, it simply would not be possible to live without a car in most places in America. Urban sprawl, lack of decent bike lanes and unwary drivers would make biking impractical if not dangerous, especially with kids. Before we moved to Germany, my wife worked 30 miles from home and I went to school 60 miles away, and the only way we could have moved closer would have been to quit my job. Even going into town meant driving a couple of miles along a stretch of highway with a 55 mph speed limit and no sidewalks. Bus service was spotty at best, and train service a joke. To live without a car there would have been virtually impossible. But maybe if more people were willing to try it, more places would devote the resources necessary to make it feasible.

Sometimes I wonder how long it will take me to fall back into the habit of driving everywhere again, if and when we move back to the US. As it stands, I’d be happy to live the rest of my life in a place where I don’t need to own a car. But at the end of the day I can’t deny that a part of me would still love to drive one now and then. After all, I am living in the land of the Autobahn.

]]>

Polyglot Bible; image by sukisuki on Flickr, by Creative Commons licence.

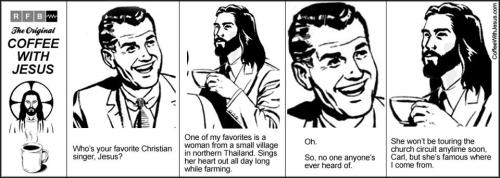

Perusing the bewildering array of sessions at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting, it would be easy to wonder whether “Fostering Biblical Scholarship” (our official mission) can mean fostering just about anything to do with the Bible. Is there anything beyond an interest in the Bible itself that holds us together as a society? What, after all, has “Bakhtin and Biblical Imagination” to do with “Economics in the Biblical World,” “Linguistics and Biblical Hebrew” to do with “Bible and Film”? Are our approaches to the text so diverse that there isn’t even a common standard of measure?

I have a theory: The art of biblical scholarship—all biblical scholarship—is the art of making meaningful connections between a text and something else. “This text is better understood in connection with X” or “X is better understood in connection with this text” could summarize the vast bulk of what we call biblical scholarship. That might seem like nothing more than a restatement of the problem, since X could be almost anything: another text or set of texts, another aspect or portion of the same text, a tradition or source or redactional layer, a scribal practice or transmission error, the history of transmission, the history of tradition, a genre or typescene or trope, a symbol or metaphor or any other particular form of language, a literary theory, a sociological theory, a way of life (whether ancient or modern), a ritual or custom, an archeological find, an image or icon, a people-group, an historical event, a theory of history, a theory of midrash, a theory of myth, a theory of mind, a method or methodology, a social, religious, political or economic movement, a philosophical system, a theological system, a theological tenet, a theological error, an ideology, modern science, ancient science, modern film, medieval children’s stories, teaching, preaching, blogging.

But this is not just to restate the diversity of biblical scholarship, it is also to see that each of these otherwise very dissimilar topics shares a similar structural relation to the text. Each of them is drawn upon to argue either that some aspect of the text can be seen more clearly in the light of the thing to which it is compared, or vice versa. Such a wide range of things to which the text can be connected explains the wide range of kinds of scholarship we engage in, the wide range of standards of evidence and argument we employ, and the wide range of conclusions we come to, but all such comparisons operate within a similar set of parameters.

Namely, virtually all good biblical scholarship, regardless of its methods and emphases, 1. makes an original connection, 2. provides compelling reasons for accepting that connection, 3. acknowledges the limitations of the connection, and 4. shows how the connection helps us to better understand either the text or the thing to which it is compared. Whether focused on historical criticism or queer theory, semiotics or Christology, any good biblical scholarship will try to show how the connection it proposes is original, convincing and fruitful. Any particular piece of scholarship may focus on one of those areas more than others, but one cannot completely ignore any of them for long.

When biblical scholarship goes bad, it tends to happen on one of those same points (whether due to poor writing or poor thinking): Either it fails to make connections that are original or non-trivial, or it fails to offer cogent, relevant and compelling reasons for accepting the connections it proposes, or it fails to counter damaging objections to its proposals, or it fails to show a significant interpretive pay-off that would result from accepting them. Non-scholarly readings of the Bible, in general, are uncritical in their making of such connections–even if sometimes insightful–but they cannot avoid making them, whether they are drawn from one’s personal life, social context, theological framework, secondary sources, or their own familiarity with the text. All of us are in the business of making connections with the text; what makes our reading of the Bible “scholarship” is our attempt to do so critically, by being explicit about the reasons, sources and implications of our proposals.

That’s my theory, anyway. Whether it is original or has any interpretive pay-off, I’ll leave for you to decide.

“The High Septon once told me that as we sin, so do we suffer. If that’s true… tell me… why is it always the innocents who suffer most, when you high lords play your game of thrones?”

George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones may be the most “realistic” fantasy novel I’ve ever read. It’s extremely well-detailed, emotionally gripping, endlessly surprising without being improbable, and unflinchingly dark. This is no children’s fairy tale, but a deeply troubling and moving epic, full of violence, brutality and sex, but also honor, valor and humor. Driven by its characters more than its plot, it gives us images of humanity at its best and (more often) worst.

Though set in a fictional world rather like Middle-Earth, there are no elves or dwarves or orcs, in fact little supernatural activity of any kind. But if there is no magic object to find or destroy, there is also no single villain to expose and defeat. The action is driven by the intrigues and wars of seven kingdoms, none of which are fully innocent nor guilty. The attention is on the Stark family, who mostly try to be noble, with varying levels of success, as they face off against the Lannisters, who mostly range from arrogant to conniving to downright wicked. If in most other series the Lannisters would be nothing more than the hissable villains, though, Martin refuses to let us hate them all. In fact, the most entertaining character of all is a Lannister.

The book allows for a spiritual dimension to the world–both giving piety a central role in many of its characters’ lives and in hinting at monsters on the edge of the world–but it is men and women who are most to be honored and feared here. The gods are real–or maybe they’re not–but it is the selfish and selfless, cowardly and courageous decisions of human beings that drive this story, often to heartbreaking ends. There may be a dark evil force on the horizon, but there is unquestionably one in the human heart, turning friends against one another, and twisting even honor and loyalty to ruin, while the wicked walk free and seize power.

The story is told through the eyes of several different characters (each in separate chapters), which pays off beautifully, giving the book a great deal of psychological depth. At times, though, Martin makes surprising choices about which character to follow at key points. This is never more obvious than when he refuses to give us a first-person view of the two climactic battles in the book. The first is experienced through a person too far away to see more than fragments. The second and decisive one is even further removed, as we only hear of it as it is described to a character on the losing side, well after the fact.

At first this seems disappointingly anticlimactic, but maybe that was the point, as it prevents us from feeling too smugly victorious, ignoring the trail of blood that led there. Unlike so many other fantasy books I’ve read, the emotional climax for me came not at the turning of a battle, but in a quiet decision to give up vengeance for honor and solitude for brotherhood, a decision that almost no one else saw.

And more than anything, that is what makes the book so enjoyable, despite its darkness: that there are still people left–broken and flawed though they are–who will choose nobility and justice even if it kills them. And unlike in most books of this sort, it often does.

]]>

Many people seem to feel a strong taboo against writing in books. Maybe they don’t want to ruin the aesthetic of a clean printed page. Maybe they don’t want to disrupt the author’s train of thought. Maybe they just can’t bear to stop reading and pick up a pen. All very noble ideals, no doubt, but not very practical for serious research. In my opinion a book is a tool, and as much as we all wish we were Will Hunting, most of us need to do more than just read if we hope to remember the details later, and marking up a book is probably the quickest way of facilitating later recall. Besides that, no book is entirely correct or in all parts equally insightful or useful, and I see no problem at all with indicating your judgments on such matters directly in the book itself.

Personally, the only times I bother restraining myself from underlining and adding marginal notes are: 1. when I’m reading fiction purely for pleasure, 2. when the book is so lousy that nothing seems worthy of underlining, but not so outrageous as to demand vigorous rebuttal, or 3. when I do not own the book. And there’s the rub, since as a poor graduate student I simply cannot afford to buy most of the books I must use.

If I do own the book, or have a photocopy of it, I mark it up like crazy, underlining everything significant or interesting, starring anything especially important to remember, and even writing little notes and comments in the margins. I always do this in pencil, in part because I find the grey less obtrusive than a pen or (worse) a highlighter, but most of all so that I can make adjustments if I change my mind about what was important, or realize a particular marginal note has misunderstood some key point (which of course, never happens to me!). When I can underline in this way, I generally do not take external notes on first reading, except when I am struck by some novel thought that requires fuller discussion than is possible in the margin.

This approach makes for a messy book but not only does it take far less time to underline than it does to summarize the key points in a separate document. It also facilitates finding the information I’m looking for later in a way that even detailed notes do not necessarily improve upon. Not only do you have the key information already marked on the page, but the simple act of underlining requires you to read the line at least twice, and stopping to add a marginal note only further solidifies the idea in your head. Both require you to pay fairly close attention to the position of the text on the page, and I often find that even months later I can remember approximately where on the page the information I underlined will be, if only I can find the proper page.

Even more valuable is that marking up a book or article in this way allows one to reread it by skipping from underline to underline, which takes a fraction of the time of rereading the whole book, while still capturing the main points. I find that if I do this immediately after finishing the full work for the first time, I can not only quickly take fuller external notes (in a notebook or on my computer, depending on my mood), but I am also in a much better position to evaluate the value and validity of the author’s statements than I was upon first reading (and I can always reread the larger context around the underlining, if necessary later). By contrast, when I have not been able to mark the most important lines in a work, a second reading takes virtually as long as the first, and is only feasible for the most important resources.

In short, I find that by marking up my books and articles, and only afterwards taking fuller notes from the underlining, I can read both more quickly and more effectively than trying to both read and take notes at the same time. The trouble, of course, is that I cannot do this with library books. Well, I have done it with library books, but I’m older and wiser and hopefully a lot more considerate than that now. And in any case, I have a feeling Göttingen’s libraries would be far less forgiving of that sort of thing that my old liberal arts college.

What to do then? So far none of the solutions I have found are ideal: Either I photocopy or scan all the key parts of the book (as I always do for articles) and mark up the photocopies as usual, or I take detailed notes while reading, combined with the use of sticky notes or page flags.

The problem with the first, aside from the little legal and ethical issue of copyright violation, is that it really isn’t practical to photocopy the whole of any but the shortest books, and it is often difficult to predict in advance how much of the book will actually be worth reading in detail. I’ve often found that many of the sections I photocopied either prove unnecessary, or else depend on some other section that I had not photocopied. There is also the expense of the photocopies themselves, and though I am currently blessed with a virtually unlimited budget for that sort of thing (I sure wasn’t while writing my M.A. thesis!), there is still the environmental issue and even the practical problem of having piles of photocopies everywhere.

Using digital scans on the computer or similar device could alleviate some of these concerns, but I’ve yet to find a digital technology that allows all that I would want to do with a book, from smoothly flipping through, to naturally taking notes in context, all while sitting back in a chair rather than leaning over a desk. I also find that I write better when I can lay out my sources and notes side-by-side while I am writing, and even having a second screen for the computer is not sufficient to replicate that experience. As much as I still long for the day when I could carry all my books and notes around in my pocket–if not as a replacement, at least as a supplement–I don’t see that happening any time soon.

As for skipping the copies and just taking full notes as I read, this is feasible if the book is only tangentially relevant to my interests, such that I only need to keep track of a few of the points it makes, but if it is a monograph devoted directly to the question I am currently researching, this method is way too time consuming to be practical. It takes long enough to read a 300 page book without taking notes, but it takes 10 times as long if I try to type or write out summaries or quotations of all the key points as I go. Unfortunately, failing to do so makes it far less likely that I will be able to remember or find the required information later, even if searchable online versions have made that somewhat easier.

If I know that I can keep the book for a while, I can take less detailed notes if I combine them with sticky flags stuck to the pages of the book themselves. This is still less precise and more time consuming than underlining, but for longer and more important books that cannot simply be purchased or photocopied, it is better than nothing, at least until I have to remove all the flags and return the book. My main problem with this, though, is that unless you use a whole lot of them, such flags can only point out the general part of the page and not specific sentences. I also find that the more flags I use, the more difficult it becomes to flip through the book, and the less useful they are as a means of quickly finding an important section later.

My latest method, which I like quite a bit better, uses little strips cut from sticky-notes, not to hang off the page as flags, but simply stuck in the margins in place of underlining (pictured at the top and in close-up here). It is no substitute for underlining when I can do that, but it needn’t take any longer and can be nearly as precise, without disrupting page-turning like too many flags do.

I simply cut a very thin strip of sticky-note and put it directly next to the sentences that I wish to highlight, cutting it down or adding additional depending on how long a section I need to emphasize. For important details, I use a brighter color like pink, and for especially important points, I can still hang a flag off the edge of the page like normal. Full size sticky-notes can also be used in place of marginal notes, so long as one does not go overboard with them.

Using this method, I can then go back through the book a second time to take fuller notes nearly as well as I could with an underlined copy, without having to do any damage to the book itself. It also saves greatly on the number of sticky-notes I need to use, and should I need to return the book, I can always scan the marked pages before doing so and keep the digital copy for context, without needing to print it off (since it is already marked up), nor needing to determine in advance how much of the book I’ll need.

So that’s my current approach. I’m sure it could use improvement (one trouble I anticipate is the little strips falling out too easily), but in the mean time I’m curious what methods other people use to keep track of what they read. Do you aim for speed and efficiency, or do you have a more detailed and methodical approach? Either way, what tips and tricks have you found?

]]> Images copyright Warner Brothers.

Images copyright Warner Brothers.

Love is stronger than death. – Unknown