| CARVIEW |

Lady Susan

by Jane Austen (1794),

(in Northanger Abbey, Lady Susan, The Watsons and Sanditon).

Oxford World’s Classics, 2008 (1871).

Will you walk into my parlour?” said the Spider to the Fly,

‘Tis the prettiest little parlour that ever you did spy;

… Oh no, no,” said the little Fly, “to ask me is in vain,

For who goes up your winding stair can ne’er come down again.”

This was my July 2013 review of Austen’s Lady Susan, reposted just as a film adaptation arrived in cinemas (though rebranded with a completely different Austen title as Love & Friendship – written when she was in her teens).

Are tweets a modern equivalent of Lady Susan‘s letters? And if so, how would public responses be written if, instead of handwritten letters, the emails of Lady Susan Vernon and other contemporaries were published piecemeal on the internet for general titillation?

It’s worth noting that, back in 2013, each tweet (as they were then called) was limited to 140 characters.

@calmgrove 5 Jul

Lady Susan Vernon seems a nice woman: very family oriented, recently widowed, keen to have daughter well educated. What’s not to like? Hmm?

@calmgrove 5 Jul

Ah. Lady Susan presents a different face when writing to friend Mrs Alicia Johnson: outrageous flirt, cruel mother, muckstirrer. Worrabitch!

@calmgrove 6 J

Lady Susan’s sister-in-law, Catherine Vernon, thinks her own husband gullible and Lady Susan manipulative. Who’s the unreliable narrator?

@calmgrove 6 Jul

Catherine V’s brother Reginald hears reports that Lady Susan is an ‘accomplished Coquette’ and ‘distinguished Flirt’. You just fear for him.

@calmgrove 6 Jul

Lady Susan foists herself on her brother- and sister-in-law for Christmas. No love lost between the two women but they play the game.

@calmgrove 6 Jul

Letter 7 very revealing. Lady S thinks daughter Frederica stupid, with ‘nothing to redeem her’, but must be married off to vapid Sir James.

@calmgrove 6 Jul

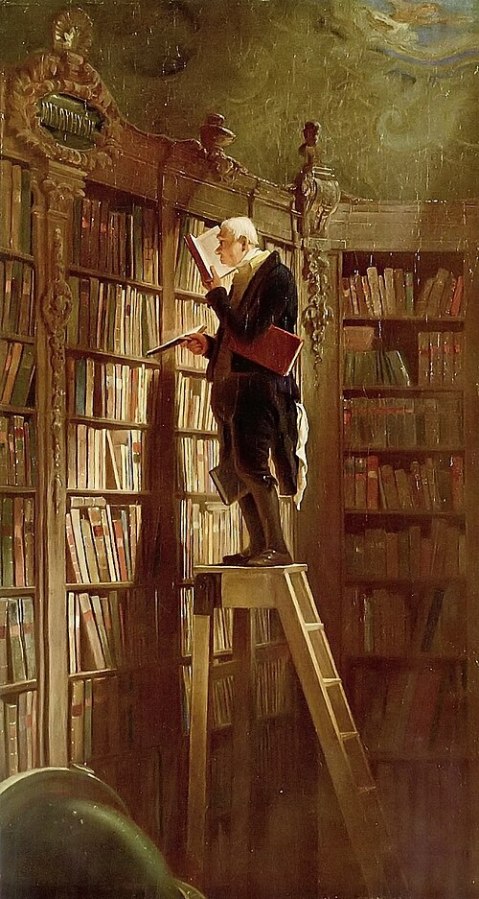

What tangled webs she weaves! Lady S now intent on ensnaring poor Reginald de Courcy. Indulged as a child, she’s now a spoilt sociopath.

@calmgrove 7 Jul

Reginald’s sister and parents very concerned about man-eating gold-digging Lady S, but fly in spider’s web does not control his own destiny.

@calmgrove 7 Jul

OMG Lady S’s daughter’s got wind of plans to marry her off to young fogey Sir James and has run away from school! Caught. And now expelled.

@calmgrove 7 Jul

So, now Frederica’s at her uncle and aunt’s house with her mother. Turns out she’s pretty, not stupid, but shy. And ogling Reginald. Oops.

@calmgrove 7 Jul

Consternation! Ardent Sir James has followed Frederica. The young girl turns for help to Reginald, object of her ma’s regard. Cue uproar!

@calmgrove 7 Jul

Halfway through tweeting review of Austen’s Lady Susan, recalling Jane writing this was only a year or so older than 16-year-old Frederica.

@calmgrove 8 Jul

Lady S’s machinations could blow up in her face but she deftly averts disaster: Reginald’s assuaged, Catherine managed, Sir James sent home.

@calmgrove 8 Jul

The merry widow’s ‘gay and triumphant’ again, plans her wedding to Reginald and Frederica’s to Sir James. But Frederica *sad face* still.

@calmgrove 8 Jul

Self-congratulating Lady S resolves to punish all who defy her, Frederica, Reginald and Catherine; plans return to London for capital fun.

@calmgrove 8 Jul

Frederica left behind with aunt and uncle while Lady S intends shenanigans in Town with wife-cheater Manwaring and/or Reginald de Courcy…

@calmgrove 9 Jul

After a few weeks in the country playing games with people’s lives and feelings Lady S removes to London, where affairs start to unravel.

@calmgrove 9 Jul

As in the best farces the action comes thick and fast: Lady S, persona non grata with some and over-familiar with others, hears bad news.

@calmgrove 9 Jul

Reginald hears of Lady S’s affair with a married man and dumps her; friend Alicia is forbidden contact with her. Can anything else go wrong?

We don’t know what title Jane Austen would have intended to give this novel if it had been published in her lifetime; but when it eventually appeared more than half-a-century after her death it was called Lady Susan after the character who sits at the centre of a web of intrigue, tweaking the threads of everyone she comes into contact with. I find it extraordinary that Austen, who probably began this in 1793 when only eighteen, was able to so convincingly portray such an attractive but utterly ruthless widow in her mid-thirties. This she achieved despite being not much older than Frederica, the unhappy daughter of Lady S.

Whilst we abhor the crimes of the selfish protagonist of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley we are fascinated by his close shaves and perhaps secretly thrilled by his successes. It helps that many of his dupes are painted as rather less than likeable and that Ripley’s desires are largely aesthetic. Lady Susan’s dupes, although they are bland and usually weak, are however largely innocent, and her desires for wealth, status and the thrill of the chase can seem merely venal in comparison. We want her to fail in her machinations because, despite her famous beauty, youth and quick tongue, she has no redeeming features that we can really empathise with.

As it stands the novel has rather an abrupt ending. It may be that Austen, having concocted forty-one letters purporting to be from some half-dozen correspondents, found that she had fallen out of love with her coquette and simply stopped the tale. Or that she was unsure how to take the tale further. It’s surmised that in 1805 she did a fair copy of her teenage novel and added the perfunctory conclusion that her posthumous readers find less than satisfying, with indications that loose strands may or may not be tied up. It’s interesting that the authorial voice intrudes here, as it certainly does at the very end both Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey: it’s as though she can’t resist adding her ironic asides, all the while with a twinkle in her eye.

Pretty much everybody, having done their homework, describes this as an epistolary novel, adding that the fashion for such novels was nearing its end in the late 1700s. Even Stevenson, setting his Treasure Island in the 18th century, included correspondence from Squire Trelawney to flesh out Jim Hawkins’ narrative in order to give a period flavour to his adventure story. As a technique for displaying characters’ motivations and thoughts, authentic voices and dissembling utterances, friendships and formalities it can often be more effective than the all-knowing third-person narrative.

Can texts, tweets and social network messages ever match the colourful verbosity of longhand missives? Their impact is very different, of course, though we mustn’t imagine that because they lacked instant messaging the Regency period wasn’t capable of several posts a day, with replies often within daylight hours.

What is crystal clear is that Austen’s wit, trenchant commentary, plot handling and surgical dissection of manners were all fully formed before she was twenty. Though critics agree that it’s not in the same league as her mature works it’s still a matter of wonder that Austen was setting so high a standard of excellence in novel-writing. And Lady Susan, while not exactly a Black Widow spider, is still for me one of the great comedic creations; it’s all the more remarkable that, where a lesser talent would ensure that natural justice was done and Lady Susan had her come-uppance, this young writer chose to make her monster survive to ensnare more victims.

This 2013 post was first republished 28th May, 2016, and again now.

]]>

What’s Bred in the Bone (1985)

by Robertson Davies,

No 2 in The Cornish Trilogy.

Penguin Books, 2011 (1991).

‘That alchemy is a pretty kind of game

Somewhat like tricks o’ the cards to cheat a man

With charming.’

— ‘The Alchemist’ (1610) by Ben Johnson.

This, the absorbing central title in Robertson Davies’s Cornish Trilogy, follows The Rebel Angels (1981) before the series is completed with The Lyre of Orpheus (1988). Like the preceding volume it deals with the fallout from the death of Francis Cornish on his 72nd birthday in 1981, and some of the dilemmas faced by the three trustees of the Cornish Foundation for the Promotion of the Arts and Humane Scholarship.

We meet the trustees, all of whom had appeared in The Rebel Angels – nephew Arthur Cornish, Arthur’s wife Maria (née Theotoky), and Professor the Reverend Simon Darcourt – of Toronto’s University of St John and the Holy Ghost – who’s also the executor of Frank Cornish’s will.

However there’s a problem: Darcourt is trying to write an official biography of the deceased, a man of great renown in Canada and Europe as an acknowledged art expert; but there are lacunae in Frank’s career and whispers about forgery, and nobody living seems to know much about his upbringing or what really motivated him.

Darcourt expresses a hope that “When his collections have been examined it may emerge that he was a more significant figure in the art world of his time than is at present understood.” For us readers, thankfully, there’s elucidation from two individuals, and in keeping with Davies’s grand plan mixing the metaphysical with the physical the pair assessing Frank’s life are disembodied entities – a tutelary spirit called the Daimon Maimas and one of the minor Angels of Mercy known as the Lesser Zadkiel. Through their discourse we learn about the intimate mysteries connected with this Canadian, in particular “the delight, the torment, and the bitterness of his life.”

Born in Blairlogie, a backwoods town in Ontario, Frank’s story actually begins before his conception, and it’s bound up with how the McRory family gets to be involved with Major – later Sir – Francis Chegwidden Cornish from Cornwall, England. Some of the family moves to Toronto, which is where Frank goes to school and then gets his first degree at ‘Spook’ (which is how the University of St John and the Holy Ghost is familiarly known).

We learn about his artistic leanings, formed from a mix of Catholic and Anglican influences and life drawing in a mortuary, and then his experiences studying Modern Greats at Corpus Christi, Oxford. It is here that he learns about ‘the profession’ pursued by his father and other men “who follow their noses and see whatever’s to be seen,” before proceeding to restoring paintings in Austria under Meister Tancred Saraceni, who tells him: “Find your legend. Find your personal myth.”

Thus far the relatively bald outline of the novel’s premise, but this being a book by Robertson Davies then the reader is promised a deep dive into alchemy, psychology, art history, hagiography, family secrets, astrology, obsessions, love affairs, Ben Jonson’s work, the Allied Commission for Monuments and Fine Arts (popularly known as Monuments Men) and much, much more. In particular we learn quite a bit about fakery and art works such as a striking portrait of a jester and The Marriage of Cana triptych being restored at Austria’s Schloss Düsterstein. Mozart had his A Musical Joke, Haydn his Surprise Symphony, Davies has his Drollig Hansel painted by the so-called Alchemical Master to make a monkey out of art experts.

What Francis discovers for himself is that ‘a great picture must have its foundation in a sustaining myth, which could only be expressed through painting by an artist with an intense vocation;’ for the artist this may involve a descent into the realm of the archetypal Mothers. Robertson Davies seems to be trying something similar in this inventive and clever novel, inbuing it with his own obsessions and his personal history, heavily fictionalised. When What’s Bred in the Bone was published in 1985 Davies was himself 72, the same age as his protagonist whose life history forms the central work in this literary triptych; Davies too was born in a small Ontario town like Francis’s Blairlogie and followed an educational path similar to that of Francis Cornish.

Let’s end with one of the novel’s many leitmotifs, a reproduction of the Pre-Raphaelite painting that Francis keeps in his bedroom: this is Love Locked Out (1890), a work completed by American artist Anna Lea Merritt in memory of her husband and housed at Tate Britain. Cupid is at the locked door of a tomb, waiting “for the door of death to open and the reunion of the lonely pair.” In the novel it spoke profoundly to Francis for several reasons, and in a way we may assume it says something about Davies at this point in his life; it does indeed seem to suggest that finding and then faithfully investing your personal myth in whatever you create is what helps distinguish the great artist in whatever medium they choose to excel at. That in itself is a kind of alchemy.

What’s Bred in the Bone was my 21st title for #20BooksOfSummer despite my delay in composing and posting this review.

Prompted by Reading Robertson Davies, a project formerly hosted by Lory Widmer Hess, by happenstance this review was first posted on the 12th September 2024, the birthday (and death-day) of Francis Cornish; it’s now reposted in advance of my review of the final part of the Cornish Trilogy on 3rd September over on CalmgroveBooks.

]]>

The Rebel Angels

by Robertson Davies

in The Cornish Trilogy,

Penguin Books, 2011 (1981).

‘Wit is something you possess, but humour is something that possesses you.’ — Clement Hollier.

John Aubrey, filth therapy, Franz Liszt, Romany lore, François Rabelais, academic feuding, Paracelsus, a bequest – all this and more are part of the ferment amongst certain of the scholars of Davies’s fictional Canadian college, fomenting the events that ultimately result in murder.

The college of St John and the Holy Ghost, known colloquially as Spook, is in some ways the equivalent of Rabelais’s Abbey of Thélème, where the motto was Fais ce que tu voudras – ‘Do what you will’; naturally, since the Greek θέλημα means ‘wish’ or ‘strong desire’, various strong wills at Spook strive to achieve what they most want, with consequences that may differ from what’s intended.

Central to the action is Maria Theotoky, a postgraduate student around whom two pairs of opposing academics battle for ascendancy, along with Arthur Cornish, whose uncle’s death and bequest helps precipitate the action of the whole drama.

Benefactor Francis Cornish has died and has left much of his collections of artworks, historic manuscripts and autographed musical scores to Spook, to be administered by his nephew Arthur Cornish, aided by Professors Clement Hollier, Simon Darcourt and Urquhart McVarish. Hollier, whose specialism is comparative literature but who sees himself as a palaeo-psychologist, has his eye on a Gryphius MS because it clearly contains some correspondence between Rabelais and the physician and alchemist Paracelsus. Soon, however, he suspects his colleague Urquhart McTavish has quietly and greedily squirrelled it away while denying any knowledge of it.

Hollier had intended his gifted student protégée Maria Magdalena Theotoky to be the recipient of the manuscript for doctoral study, but with no manuscript forthcoming things are at an impasse. It is at this point that former monk and roué John Parlabane comes into all their lives – and then things get very complicated indeed, as only Robertson Davies can devise. It’s only a matter of time before we discover the significance of the novel’s title and who the rebel angels are.

I shall tell you who the rebel angels originally were, according to apocryphal books in the Bible: Samahazai is one, and Azazel the other. Samahazai – also Shemhazai, amongst other spellings – was one of the fallen angels who slept with the Daughters of Men and engendered Giants, while Azazel was seen as the former angelic being living out in the wilderness to whom the Hebrews sent the ritual scapegoat. As the novel takes the form of two separate narratives composed by Maria and Fr Simon Darcourt it takes a while for the title’s relevance to register.

As appears the case with all of the author’s novels the text is awash with literary references, tangled plots, complex characters, intellectual niceties, witty dialogues and devilish humour. In keeping with its principal Mcguffin The Rebel Angels is a Rabelaisian romp through and through, with not so covert examples of the Seven Deadly Sins displayed prominently. To take one example, Gluttony, there are at least two principal feasts featured, the college’s Guest Night at the end of the summer term, where Rabelais’s phrase (as translated by Thomas Urquhart) “chirruping in their cups” is applied to the feasters, while a Christmas meal at Maria’s Romany mother’s house rivals Trimalchio’s dinner party in the Satyricon, where tellings using Tarot cards hint at later developments.

To counteract any impression that this is an entirely intellectual novel we are introduced to the notion of ‘filth therapy’, a concept Rabelais would have celebrated and here noted as the subject of a scientific investigation into the link between physiology, what we’d now call the gut microbiome, and inhibited defecation. You won’t now be surprised to know that Davies creatively links this with the care of string instruments on the one hand and the manner of the murder that is explicitly described on the other.

Davies mined his experiences at and memories of Toronto’s Trinity College to create credible if heightened scenarios for his Spook-set novel. As if to underline his metafictional approach he has the disreputable academic John Parlabane (whose name happens to be the first word in the text) compose an autofictional novel, part set in a college like Spook.

Entitled Be Not Another and drawn from an epigram by Paracelsus – ‘Be not another, if you can be yourself’ – Parlabane’s scurrilous fiction in reality represents a typical sleight of hand from Davies, perhaps indicating that appearances can be deceptive even as they reveal. Davies’s own fiction cleverly plays with our perceptions; having found it both witty and humorous, engaging and enjoyable, I anticipate reading more of the same in the two sequels.

First published 28th August 2023, this review is reposted in advance of a review of the final part of the trilogy. My review of volume two appears tomorrow, 2nd September 2025.

Read as one of Cathy @746.com‘s 10 Books of Summer from my list and from my 2023 TBR Pile Challenge, and also reviewed (on what would’ve been Davies’s 110th birthday) for Entering the Enchanted Castle Lory’s Reading Robertson Davies project.

Roadside Picnic

by Arkady Strugatsky and Boris Strugatsky.

Translated by Olena Bormashenko,

foreword by Ursula K Le Guin,

afterword by Boris Strugatsky, 2012.

Gollancz, 2012 (1972).

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

From ‘An Essay on Man: Epistle II’ by Alexander Pope

The proper study of mankind is man.

Superficially a speculative thriller, the Strugatsky brothers’ Roadside Picnic for me turned out to be a deeply philosophical novel under its science-fictiony veneer. For the most part it focuses on a character called Redrick, a chancer who lives for the pleasures of alcohol, tobacco, gambling and occasional sex, living at some unspecified future time somewhere in North America. So, initially, a not very edifying tale.

The ostensible premise is that extraterrestrial visitors have touched down at six points on the Earth’s surface and then just as mysteriously departed, leaving behind their detritus in what turn out to be highly dangerous, disturbance-filled Zones. It is for this debris that Redrick and others enter the Zone adjacent to Harmont, to retrieve alien junk for the black market.

But there are deeper matters to think about than mere cupidity. At the central point of the novel we find ourselves listening to a conversation about the implications of this First Contact, implications that should matter to all humankind but which if ever considered are soon forgotten. In its underhand way Roadside Picnic encourages us to quietly consider those implications.

When Alexander Pope wrote about quintessential Man as “Plac’d on this isthmus of a middle state, | A being darkly wise, and rudely great” he could easily have had in mind not just the human race in general but someone like Redrick in particular. Red is a Stalker, one of the best, expert at navigating through the toxic Harmont Zone to retrieve desired objects exhibiting perpetual motion, everlasting energy and other impossible attributes. He is happy to sell to the local branch of the International Institute of Extraterritorial Cultures or to the highest bidder, and despite official clampdowns he is generally lucky in getting away with his illegal forays.

In her foreword to this edition Ursula Le Guin describes Red as “ordinary to the point of being ornery,” and it would be easy to think this is about him and the various and varied people he comes into contact with. It would be equally easy to think this is about the absent aliens and their marvellous artefacts and thus typical of ‘hard sf’ with its focus on mechanics, astrophysics and the like. But we would be wrong to think along these lines, for this novel challenges us to think about our humanity.

For, contrary to the thinking of xenologists who might, as with certain religionists, imagine alien minds – or those of deities – to ultimately function in a way similar to humans, it may be that there’ll be in fact no way for aliens to communicate with us, or indeed for them to be aware of us. The Visit that occurred for the people of Harmont and others, and the debris they left behind, could be likened to a roadside picnic by day trippers or holidaymakers with their discarded litter, with no message of significance intended. So are we supposed to regard the novel as essentially nihilistic in tone?

I don’t think so. In many ways Roadside Picnic is a modern equivalent to the medieval quest for the holy grail. The last section of the novel is, in amongst Red’s stream of consciousness musings, a physical search for an object that might grant wishes, the attainment of which could result in the quester’s transfiguration, or the healing of mankind’s woes, or maybe nothing at all. That Red is accompanied by a young man called Arthur may or mayn’t be relevant; but that Redrick is himself a Perceval or Galahad surely can’t be in doubt.

And what is the story’s notional goal? Is it about man’s search for meaning? Is it to discover the soul of humanity? Or is it instead a chimaera, an insubstantial construct? Written before his death, Boris Strugatsky’s afterword mentions the initial notes he and his brother made for Roadside Picnic: “Thirty years after the alien visit, the remains of the junk they left behind are at the center of quests and adventures, investigations and misfortunes. The growth of superstition, a department attempting to assume power through owning the junk, an organization seeking to destroy it. …” In other words, quests which may end in failure, and questions may have no answers.

Alexander Pope in his 1733 Essay on Man wrote that Man, “With too much knowledge for the sceptic side, | With too much weakness for the stoic’s pride, | He hangs between,” adding that this in-between state rendered the individual “in doubt to act, or rest; | In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast …”

God or beast? Redrick may not have decided on which side he leans, but perhaps he asks himself whether he’s primarily a sceptic or a stoic. As this reader has often done.

Read for the tenth anniversary of #SciFiMonth, hosted by Lisa at deargeekplace.com and Imyrel at onemore.org.

Post first published 27th November, 2022, and reposted 29th August 2025, the day after the centenary of Arkady Strugatsky’s birth. I’ve also reviewed Hard to Be a God (1964) here on my CalmgroveBooks blog, and will be reading and reviewing The Doomed City there later this year.

]]>

One Billion Years to the End of the World

by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky,

translated by Antonina W Bouis (1978).

Penguin Classics Science Fiction, 2020 (1977).

“I was told that this road

Yosano Akiko (attributed)

would take me to the ocean of death,

and turned back halfway.

Since then crooked, roundabout, godforsaken paths stretch out before me.”

A physicist, a biologist, an engineer, an orientalist and a mathematician walk into an astrophysicist’s apartment. No, it’s not the start of a joke but essentially the main action of this immersive novella by the Strugatsky brothers, also translated as Definitely Maybe: A Manuscript Discovered Under Unusual Circumstances.

Set in 1970s St Petersburg, then known as Leningrad, most of the action takes place in astrophysicist Dmitri Malianov’s apartment while his wife and son escape the city’s hot and humid July oppressiveness in Odessa on the Black Sea. Here he seems to be on the brink of discovering a link between stars and interstellar matter which he dubs ‘Malianov cavities’.

But he is constantly being interrupted, by phone calls, a delivery from the deli, even a visit from one of his wife Irina’s schoolfriends. And he is not the only specialist who isn’t able to settle to achieving a breakthrough — which is where the physicist, biologist, engineer, orientalist and mathematician come in. What is there to link their inability to progress their work, and who or what is causing it?

‘All right,’ Weingarten said very calmly. ‘These events did happen to us?’

Chapter 6

‘Well, yes.’

‘The events were fantastic?’

‘Well, let’s say that the were.’

‘Well then, buddy, how do you expect to explain fantastic events without a fantastic hypothesis?’

The fantastic hypotheses these specialists come up with are that either alien beings from a ‘supercivilization’ are attempting to stop the human race from too rapidly innovating or that a Homeostatic Universe is itself trying to protect itself. These seem to be the only ways to explain why distractions, headaches, mysterious notes, warning visits, even natural phenomena, all seem to conspire to divert the scientists from their work. But are they correct in their hypotheses?

This was such a diverting read, simultaneously humorous, philosophical, suspenseful and speculative. Written during the years when Soviet Russia was under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev the novel is rife with barely suppressed paranoia, a paranoia which — despite being variously ascribed to the notion of ancient masters of the occult, alien intelligences or the Cosmos itself — aroused sufficient suspicion from the Soviet authorities that the novella first appeared in an expurgated form.

Interestingly, apart from occasional exclamations, God is never evoked as the cause of the scientists’ woes, though perhaps the concept of divine intervention in human affairs is ridiculed by the mathematician Vecherovsky:

‘Why measure nonhuman expediency in human terms? And then remember with what force you smack yourself on the cheek to kill a crummy mosquito. A blow like that could easily kill all the mosquitoes in the vicinity.’

Chapter 7

Behind the bewilderment of Malianov and his colleagues, and doubtless the bewilderment of many readers, there is a sense that the whole narrative is really a Cosmic joke — were it not for a couple of unsettling features. Firstly, the story sequence is presented as a series of numbered ‘excerpts’, each often starting or ending mid-sentence, as though extracted from a typescript by an observer. Secondly, about two-thirds or so through the text the excerpts switch without warning from third person to first person, with Malianov himself as narrator whereas before he was the observed subject. With such tricks (along with a suicide, the unexpected appearance of Irina’s friend Lida, a duplicate passport and cryptic telegrams) do the authors maintain the suspense and suspicions so essential to the creation of paranoia. And we mustn’t forget the unbearable heat and humidity that dominate events, even when a thunderstorm precedes the climax, intended to add to the oppressive atmosphere.

As my introduction to the work of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky this slim volume didn’t fail to impress. The brothers survived the siege of Leningrad, with Arkady becoming an editor and translator of Japanese and English texts and Boris working in the fields of astronomy and engineering. Their complementary specialisms feature strongly in this novella (which, incidentally, works well as the basis of a filmscript), from the boffin babble that punctuates the men’s agitated conversations to the citing of authors Graham Greene, John Le Carré and H G Wells, and what must be a quote from a tanka by the Japanese feminist poet Yosano Akiko which peppers the text and eventually concludes it.

The tanka’s bleak, fatalistic nature provides part of the yin-yang appeal of this fiction, and even unconsciously echoes the then unreported meltdown and accidents at the Leningrad nuclear power plant in 1975, not long before the novella’s publication.

Read for Novellas in November #NovNov and SciFiMonth

My first ever Strugatsky title, this post was first published 12th November 2021, and reposted 28th August 2025 to mark the centenary of Arkady Strugatsky‘s birth.

]]>

Wandering among Words 13: Incongruity

incongruous (adj.)

from Latin incongruus, inconsistent, not agreeing, misfit, unsuitable.

Call me sad if you like but I’ve always liked puns, Christmas cracker riddles and dad jokes, however groanworthy they indubitably are. For instance, ‘What do you get when you cross a policeman with a skunk?’ – ‘Law and odour.’

Okay, I’ll accept the inevitable sigh that must’ve followed. But what about the unintended puns or confusing messages that come from public notices, the ones that result from carelessness, a lack of proofreading, or simple ignorance of grammar?

I’ll talk about how such unintentional wordplay may work, but how about we first look at some examples.

I’ll start with this well-known example from the X/Twitter account dedicated to the late physicist Richard Feynman’s thoughts. This post shows what’s labelled as ‘Schrödinger’s dumpster’ (what those of us in the UK call a ‘skip’): an enigmatic stencilled message on the side reads EMPTY WHEN FULL.¹ What does it mean? Are we confronted by a metaphysical paradox, a bin that’s simultaneously void and yet also chock-a-block? Or is it simply an instruction?

Well of course this is due to a peculiarity of the English language, when verbs can be repurposed as nouns (and vice versa) or, as here, a medieval adjective may become a verb and then, in time, a noun indicating a unfilled bottle, say, or a voided plastic container.

But unclear phrasing can so easily lead to ambiguity that potentially borders on farce. Take the sign often seen on emergency exits, THIS DOOR IS ALARMED. Is it just me or do you also have a vision of the door with a shocked face – like Kevin in Home Alone or the man in Munch’s The Scream (which I think must’ve inspired Kevin’s reaction to the astringent on his cheeks)?

Instead, it’s of course a warning not to push open the door unnecessarily – or suffer the consequences! Here the ambiguity arises from ‘alarmed’ functioning both as a past participle of the transitive verb ‘to alarm’ and the verbed form of the noun meaning a warning device. As a side note, the word ‘alarm’ derives via French from the medieval Italian command All’ arme! (‘To arms!’) from which both verb and noun derive.

Here’s another public sign where it’s best not to confuse a noun with a verb. It shows in both symbolic and labelled form what North Americans would call an elevator but which Brits bafflingly call a ‘lift’ because it, well, lifts us from floor to floor. Woe betide the unwary transatlantic traveller who would mistake the noun as an imperative verb…

Note: according to this Lift sign, that it’s likely only men have the competency to operate the complex panel of buttons that move the cabin up or down. I think a significant proportion of the human race may have something to say about that.

Now I turn to road signs that are simply slipshod because of a lack of appropriate punctuation. SLOW POLICE is not of course a reflection of the ability or alacrity of the esteemed force but a command to reduce speed, by order of any officers who may soon be in evidence on the road ahead. An innocuous full stop or exclamation mark would help clarify matters, would it not?

But this road sign I spotted in Pembrokeshire takes that ambiguity to new levels, imputing qualities to innocent youngsters that must surely be inaccurate, or even libellous.

These few examples of lexical paradoxes are enough to point out that public notices often need grammarians or simply people with a working brain to phrase instructions with no hint of ambivalence. Now, how to account for the reactions some of us may have – grin, smirk, groan, snigger, grimace, belly laugh, tut or shake of the head?

Most jokes and all puns work on the principle of incongruity, which can be defined here as the presence of two incompatible meanings in the same situation. Behaviourists used to see our sudden reactions to such incongruous situations as evolutionary: if a predatory animal approached or arrived amongst a group of chimpanzees, say, screeches of alarm, screwing up of eyes and baring of teeth would alert others to the threat, and the simultaneous joining in of these responses would affirm the social bonds individuals in the group had with each other.

I first learned this theory from Arthur Koestler’s The Act of Creation (1964, 1969)² and it seemed to explain how, for example, an audience’s reaction to a stand-up comedian cracking jokes which highlighted some incongruity or other might resemble how a troop of primates habitually respond to threat. More recently a meta-analysis³ of 150 studies suggested three stages in the laughter process – initial bewilderment, mental resolution, and a potential all-clear signal – which apparently further extended Koestler’s hypothesis.

Humour, which often seems to reflect personal tastes, thus fulfils a social role, clearly. But it also has its origins in violence, the verbal equivalent of, as it were, an unexpected slap in the face. Think of the words and phrases we use whenever hilarity is provoked, such as pratfall, practical joke, slapstick, punch line – these aren’t in themselves at all reassuring. But maybe the violent reaction jokes initiate – baring of teeth, guffaws, hysterical laughter, tears – are indeed intended to consolidate communality, social ties, togetherness against adversity.

Thank goodness then that we have public bodies which unthinkingly authorise incongruous signage, for they’re merely providing additional means for us to bond socially through our group smiles and our laughter.

Have you come across other ambiguous signage? And are you familiar with alternative explanations of how humour works? Let me know in the comments!

¹ Here’s the original tweet:

² Arthur Koestler. The Act of Creation: The Danube edition. Picador, 1975.

³ A summary from Carlo Valerio Bellieni, Università di Siena: https://theconversation.com/why-do-we-laugh-new-study-considers-possible-evolutionary-reasons-behind-this-very-human-behaviour-190193

Post first published 18th January 2024.

]]>

Wandering among Words 12: the 1948 show

Normally in this ‘Wandering among Words’ feature I explore a group of words or phrases related through meaning, sense and/or etymology. This time, however, I’m going to resort to a gimmick, by examining words and phrases which first appeared in print seventy-five years ago – in 1948. (Not without coincidence this was the year I was born.)

Incidentally, the word gimmick has an American origin, appearing in the first decade of the 20th century. Meaning a trick or device to attract attention, it could be derived from gimcrack (a trifle or knick-knack) – though apparently there’s a faint possibility it’s an anagram of magic.

And as it so happens the first appearance in print of a derived word, gimmickry, does indeed date from 1948 – according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary time-traveler webpage, whence I’ve selected the terms that have most tickled my fancy … and maybe yours too!

This postwar year of 1948 was when Orwell was completing Nineteen Eighty-four, the date chosen by the simple expedient of reversing the last two digits (the novel was published the year after). Like most years 1948 saw innovations in scientific and technological fields such as xerography, a form of dry photocopying; the word was concocted from Ancient Greek ξηρός (xērós) meaning ‘dry’ and γραφή (graphḗ) ‘writing, drawing’ – from which came the trademarked term Xerox .

.

Also new was the transistor, the analog(ue) computer and hi-fi, short for ‘high-fidelity’ (from which by analogy we derive ‘WiFi’). On your brand-new hi-fi you could play your LPs or long-playing records and listen to the wireless. Meanwhile in science you could have had quantum field theory explained to you, unless of course you’d forgotten key concepts by the end because your short-term memory had let you down.

Orwell’s future dystopia was less about science and technology though, more about politics, and so we have new political terms entering the discourse in 1948. Unsurprisingly the year that saw the establishment of Israel as a state introduced the adjective Israeli, now regretfully very much in the news. Three years after the United Nations was set up the world also started hearing about quasi governmental organisations, now usually called non-governmental organisations or NGOs.

After the first hijacking of a commercial flight occurred in July, the term air piracy became current; greyer areas in wrongdealing saw sweetheart deals becoming a familiar term, along with sleaze, a neologism derived from Silesian (‘sleezy’) cloth which was supposedly flimsy and so applied to dubious politicking. Sadly we are much too familiar with political sleaze.

More liberal virtuous folk may have preferred to involve themselves in ecumenism, from a Greek concept οἰκουμένη, ‘oikoumene’ meaning the whole inhabited earth (οἶκος signifies ‘home’) and in 1948 applied to the movement to promote unity among established Christian churches. Ursula Le Guin was later to borrow a form of the word as ‘Ekumen’, applying it to the successor of the League of All Worlds in her Hainish cycle of speculative novels – much as the United Nations was the successor of the less than successful League of Nations.

In the real world of 1948, however, and in private, couples might’ve only just become aware that what they often indulged in was now known as the missionary position (doubtless because the first Kinsey report, ‘Sexual Behavior in the Human Male’, was published that year). Hopefully there was never a need for either partner to resort to a panic button because, although the device had been installed in bombers during the Second World War, systems incorporating such devices were only just being installed for security in business premises around this time: it would be a while before personal panic alarms would become generally available.

In terms of public media, changes in approaches to journalism and the press led to the term cover story becoming familiar in 1948, along with kiss and tell stories. Pop culture was alive with fashion terms after the deprivations of the war years: the figure of the supermodel (as opposed to a ‘super’ model or a super-model) rose to further prominence, beside which ordinary fashion models may possibly have been uncool. Cool people must have started playing the card game canasta around now, because I remember growing up in the early 1950s with memories of my mother inviting her friends over to play the game.

The phenomenon of the line dance existed before 1948 but apparently this precise phrase first appeared now: it must’ve been the ideal activity to counteract over-indulgence in vodka martini, arancini or fusilli, the last two possibly purchased from a deli, an abbreviation of the German delikatessen or Dutch delicatessen, the place to buy savoury delicacies. If you were a messy eater you could take your soiled clothes to one of those newfangled launderettes, perhaps driving there in your estate car.

It may be tempting to think compilers of such lists may be taking the mickey but I assure you I’ve checked the background to many of these examples. (By the way, ‘taking the mickey’ is Cockney rhyming slang, short for Mickey Bliss = ‘piss’.) However, while some of the terms may seem to have been spur of the moment neolgistic inventions, a fair number have a long back history although not appearing in print precisely in this form before 1948. I don’t think I’ve dropped a clanger in this respect – anyway, I’ve come too far to rejig this post!

It just remains for me to note two final terms in the field of linguistics. First is Linear A, an early Minoan script from ancient Crete that remains undeciphered since it was first identified. The term was actually coined in the early 1900s by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in order to distinguish it from Linear B, a script only shown as late as 1952 to be in Mycenaean Greek; I’m assuming the phrase being assigned to 1948 is because it was when it first came to the notice of the general public. The other term is proto language, a lost parent language from which it’s hypothesised certain modern languages may be derived. Whether Linear A was one of these has yet to be established.

And with this etymological mystery I’ve come to the end of my retrospective wordy jaunt. If you fancy seeing what words and phrases first saw the light of day the year you were born this is where you can explore: https://Merriam-Webster.com/time-traveler/2022

First published 3rd December 2023. Incidentally, this post’s subtitle is in reference to a precursor of Monty Python’s Flying Circus: featuring Tim Brooke-Taylor, Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Marty Feldman and Aimi MacDonald, it was broadcast in 1967 and titled At Last the 1948 Show

]]>

!!!!! Inelegant, admittedly, but so is its overuse.

!!!!! Inelegant, admittedly, but so is its overuse.