| CARVIEW |

Recently, I wanted to better understand how the Cardano blockchain works on a technical level, in particular how the ledger and smart contracts work. Cardano is a rapidly moving target, and I had some trouble finding an accessible, yet detailed introduction. So, I decided to write up an introduction myself, after browsing through the documentation for Cardano, the (separate?) documentation for Plutus, the research papers, and the formal specifications. For me, the most accessible summary was M. Chakravarty et. al.’s paper “Functional Blockchain Contracts”, though for some reason, this paper still has draft status.

Cardano is a decentralized blockchain platform built on a proof-of-stake consensus mechanism. The main cryptocurrency on the Cardano blockchain is called ADA, named after lady Ada Lovelace.

Cardano is developed by the Cardano Foundation. You can find more information about their goals and ecosystem on their website. In this post, I would like to focus on the technology and give a brief, yet accessible introduction to how the Cardano ledger works, i.e. how transactions and smart contracts work. For more insight into the consensus protocol that is used to add transactions to the blockchain in real time, I refer to a blogpost by E. de Vries.

The Cardano Ledger

Basic transactions

This section presents the information you need to make sense of basic transactions on the blockchain, which you can view with e.g. the Cardano explorer.

A blockchain is a decentralized ledger. This ledger records transactions between different parties. A simple example of such a transaction is one where Alice (A) sends some quantity of digital currency to Bob (B). In the Cardano blockchain, this digital currency is called ADA. The following figure illustrates a transfer of four ADA from Alice to Bob:

The illustration shows the state before the transaction above the horizontal line, and the state after the transaction below the line: Before, Alice owns 4 ADA, while afterwards, Bob owns 4 ADA.

Unlike in the traditional banking system, where the bank authorizes who can submit transactions, anybody can submit a transaction to the blockchain. However, we have to make sure that only Alice is authorized to add this transaction to the ledger; otherwise, the system becomes useless, as e.g. Bob could attempt to add this transactions for his own benefit without confirmation from Alice. In a blockchain, this authorization is done using public key cryptography: Alice has a private key, which she uses to digitally sign the contents of the transaction. Using Alice’s public key, anyone can verify that it was indeed Alice who signed the transaction, but only someone who knows the private key is able to produce this signature. Typically, Alice uses a wallet software to manage her private key and sign transactions. The following figure illustrates the signed transaction:

If we know Alice’s public key, we can check that the signature is valid and that it was indeed Alice who authorized the transaction. In fact, the blockchain does not keep track of which key belongs to whom; Alice’s public key is simply included in the transaction data. Nothing prevents Alice from using multiple public and private key pairs, corresponding to different “accounts” or “wallets”.

The flip side of not relying on a bank to authorize transactions, and possibly revert them in the case of abuse, is that the security of your money is tied to the security of your private key. Specifically, a) you need to keep your private key secret, because other people can spend your money if they know it, and b) if you lose / forget / hide too well your private key, nobody, including you, can spend your money anymore. It cannot be stressed often enough: Your private key = your money!

In the real Cardano blockchain, parties are not identified by their public keys; instead, money is transferred between addresses. A party can use as many addresses as they like. While the public key of Alice is included in the transaction, the public key of Bob is not included, only one of his addresses. We will explain the relation between keys and addresses in more detail below.

In addition, the Cardano blockchain allows transactions between multiple addresses at once. For instance, a transaction may transfer money from one address to, say, two different addresses. The following figure illustrates a transfer of four ADA from address A, three of which go to address B, and one of which goes to address C:

The Cardano blockchain is public. Anyone can view the transactions on the Cardano explorer. For example, the transaction with ID 825c63… takes 42.42… ADA from an address and transfers 5 ADA to one address and 37.25… to another. In addition, 0.16… ADA is taken as a fee for including the transaction in the blockchain.

It is worth noting that the Cardano ledger does not record total balances of money owned by different addresses. It turns out that this simplifies the ledger model; we will discuss this below. Here, we merely note that storing total balances is not necessary, because the blockchain is public information, and one can compute the address balance by following all transactions from the beginning. The Cardano explorer does that automatically; for example, at the time of this writing, the address addr1q8kzwv… was involved in two transactions and has a total balance of 0 ADA.

On the Cardano blockchain, transactions are grouped into blocks, and blocks are grouped into epochs. This is relevant for determining which of the submitted transactions are to be included in the ledger, via the proof-of-stake consensus protocol, but as far as the currency is concerned, the grouping is irrelevant.

UTXO

While the previous section explained how to read basic transactions on the Cardano blockchain explorer, this section will present more details on how transactions are constructed. For example, many transaction which represent a simple transfer of currency between two parties are built using three addresses, one input and two output addresses, and sometimes even many more addresses. The reason is that Cardano uses an unspent transaction output (UTXO) model, similar to Bitcoin, which we will explain here.

On the surface, transactions in the unspent transaction output (UTXO) model may look like transfers of funds (money) between addresses, as described previously. However, on a deeper level, the UTXO model is better understood if we take a radical departure from the idea that addresses act as containers for funds. Instead, in the UTXO model, the containers for funds are the transaction outputs. Each transaction consists of a unique transaction ID, a set of inputs, and a list of outputs. Conversely, each output is uniquely identified by its position in the list of outputs and the transaction ID of the associated transaction. The inputs of a new transaction that is added to the blockchain are always references to previous outputs; moreover, once an output has been used as an input to a new transaction, it cannot be used a second time. Put differently, the inputs of new transaction may only refer to unspent transactions, which have not been used as input to another transaction yet. The fact that outputs are associated with addresses and funds is not relevant for being able to connect the inputs and outputs of transactions. The following figure illustrates the blockchain as a set of transactions with connected inputs and outputs

Here, the grey boxes within each figure correspond to inputs (above the line) and outputs (below the line). Each output can be connected to exactly one input; this is visualized by a dangling black line (output) which connects to a dangling red line (input).

The Cardano explorer is not a direct visualization of the UTXO model, because it does not directly show which transaction IDs the inputs reference. However, one can often infer this information from the addresses and funds associated with the input. For example, the address addr1q8kzwv… is involved in two transactions. The last output of the first transaction 34d8… is the input to the second transaction 825c…, because both the address and the amount of ADA are identical.

Funds and addresses do become important when validating transactions. For example, a transaction must conserve funds: The sum of funds of the inputs must be equal to the sum of funds of the outputs (minus a small transaction fee). We will discuss this in the next section.

Transferring funds between parties within the UTXO model often involves multiple inputs and outputs. For example, consider an unspent transaction output which contains 5 ADA. Any transaction that wants to use this output must use the entire sum. If we want to transfer 4 ADA to another party, we cannot do this with a transaction that expects 4 ADA as an input — we would not be able to connect it to the output, because an input and an output must match identically. However, we can create a transaction which takes an input with 5 ADA and transfers 4 ADA to one output with an address belonging to the other party, and 1 ADA to a second output with an address that is under our control. Many transactions on the Cardano blockchain are of this kind, for example the transaction 825c63…. However, it may also happen that we want to transfer 4 ADA, but only three outputs with 1.5 Ada each are available that are owned by us. In this case, we create a transactions with these three inputs and with two outputs, one that sends 3 Ada to the other party, and one with the remaining 0.5 Ada and an address owned by us. For example, the transaction 1bab… uses this scheme, as all the inputs have the same address.

This UTXO approach to transferring funds may seem a little roundabout at first, but the advantage is that all validity checks are confined to transactions — we can connect transactions in any way that adheres to the UTXO principle (each output is spent fully and at most once), and be guaranteed that the ledger conserves money as long as each individual transaction is valid. This simplifies the ledger model, and is an example of “compositionality”.

Transaction Validation

Having explained how inputs and outputs are connected via the UTXO model, we next turn to the validation of transactions, which is arguably the most important task of a blockchain. We will look at addresses and public keys for authorizing transactions in this sections, and discuss smart contracts in the next section.

The validation of transactions is what enables blockchain ledgers to store monetary value. To be considered valid, a transaction must pass several checks; only then can it be included in the blockchain ledger.

First, the transaction must conform to the UTXO model, i.e. every input refers to a unique unspent output. This effectively prevents double spending of funds.

Second, money must be conserved. The funds associated to the inputs may be redistributed and be assigned differently to the outputs, but the sum of funds of the inputs must be equal to the sum of funds of the outputs, minus a small transaction fee.

Third, the transaction must be authorized by the parties that own the addresses associated to the inputs. As mentioned in a previous section, this is done using public key cryptography. However, an address is not a public key, instead, it is the hash of a public key. This is a neat trick to reduce the size of the addresses. That said, it is impossible to check a signature by using just the hash of the public key. Thus, the transaction explicitly lists all the public keys that hash to the input addresses, thereby revealing the public keys. The transaction must be signed by all corresponding private keys (which must be kept secret by the parties). However, the public keys of the output addresses are not revealed; this saves space, and adds an extra layer of cryptographic protection by not exposing the public keys to a possible (though likely hopeless) offline cryptanalysis.

With these validation checks, the ledger is suitable for storing monetary value.

However, by allowing more complicated validation logic, we can support smart contracts, which are automated contracts for transferring funds and data. To this end, the Cardano ledger associates inputs and outputs not just with funds and addresses, but with additional, custom data which encodes the state of the smart contract. This leads to the Extended UTXO (EUTXO) model, which we discuss in the next section.

At the time of this writing, the data supported by the Cardano ledger, and also its data format, are not set in stone: From time to time, the Cardano blockchain will undergo a hard fork where the ledger format changes. However, thanks to a special programming technique known as a hard fork combinator, these forks are almost seamless: existing transactions on the ledger will be unchanged, and are compatible with all future transactions that are added to the chain. The Cardano ledger has already undergone a number of hard forks; the data formats are documented in formal specifications. The Cardano blockchain started with the Byron format, which supported UTXO model transactions of Ada. Then came the Shelly format, which enabled stake pools and staking rewards. The Mary hard fork enabled multi-assets (Shelly-MA), i.e. the transfer of tokens or currencies besides Ada. The Alonzo hard fork will enable smart contracts.

Smart Contracts and EUTXO

Blockchains can automate not just simple transfers of money, but also more complex exchanges involving multiple parties and conditions. Smart contracts are pieces of software that describe such exchanges.

On the Cardano blockchain, smart contracts are identified by their addresses. Instead of sending funds to an address controlled by a human, you can send funds to an address representing a smart contract, which will then perform some automated transactions involving your funds. By looking at the source code for this contract beforehand, you can understand exactly what the contract is going to do. The validity checks on the blockchain ensure that the contract is executed exactly as specified.

A simple example of an exchange suitable for a smart contract would be donation matching: Whenever Bob receives a donation, Alice wants to match that donation with an equal amount of money. One possible implementation in terms of a smart contract would would work as follows: First, Alice sends the funds she wants to use for donation matching to the contract. Then, any willing donor, say Dorothee, sends money to the contract, which will then automatically forward this money plus an equal amount of matching funds to the address owned by Bob.

This example shows that smart contracts often involve multiple transactions: Alice makes a transaction that transfers funds to the contract, and Dorothee makes a transaction that donates to Bob. These transactions need to adhere to the contract rules, e.g. that Alice is the first to make the transaction, and Dorothee must come second. Any smart contract consists of two components: an on-chain component, which ensures that transactions adhere to the contract rules, and an off-chain component, which is a program that Alice or Dorothee use to submit rule-abiding transactions. The on-chain component never submits any transactions to the blockchain, it only checks existing transactions for validity. The on-chain component is run on the nodes that validate the blockchain ledger, while the off-chain component is run by the user, e.g. as part of his wallet. For Cardano, the Plutus platform allows us to write both components using the same programming language, Haskell.

The on-chain component of a smart contract operates like a state machine. When an output of a transaction is a smart contract address, this address has to be accompanied by additional, custom state data. This data represents a new state of the contract. Here, the same hashing trick as for addresses is used: Only a hash of the data, not the data itself is included in the transaction. But when the input of transaction references this output, via the UTXO model, the data is included in full. In addition, this input has to come with additional, custom data called a redeemer, which has the role of user input, and corresponds to a state transition label for the state machine. The UTXO-like ledger model which includes state data and redeemer data is known as the Extended UTXO (EUTXO) model.

For example, the donation matching example above can be implemented with the following state machine:

The machine has a single state Funded addrA addrB, which indicates that the contract is funded and ready to match donations for Bob. This state stores both Alice’s address addrA , and Bob’s address addrB. The possible transitions are Donate for making a matched donation to Bob, and Refund to return Alice’s funds when she wants to end the fundraiser. The state machine may seem somewhat unusual in that the contract state does not contain information about Alice’s total funds, and that the donation amount is not recorded in the Donate transition. However, there is no need for this, because transaction inputs and outputs always store an amount of funds.

The on-chain component can implement this state machine by only accepting the following transaction (schemas) as valid:

Here, the first transaction schema corresponds to a Donate transition. It takes an amount y from Dorothee and transfers twice that amount to Bob, using the funds held by the smart contract input. The second transaction schema corresponds to the Refund transition. It returns all the funds in the contract to Alice by spending the input contract. Here, we have also added an input from Alice (with zero funds) in order to make sure that not only does all the money go to back to Alice, but also that only Alice can initiate a refund: As her address appears in the input, this transaction is only valid with her signature. Similarly, as the smart contract address appears as an input, the validator code of the smart contract is run on this transaction. By refusing all transactions that do not fit into these two schema, only valid transitions of the smart contract state are possible. (The description here is a bit oversimplified in that we have ignored transaction fees and the fact unspent outputs with zero funds are not allowed. Transactions on the blockchain always involve a small fee.)

Finally, to start a fundraiser for Bob, Alice can submit the following transaction to the chain.

This transaction creates a smart contract output with funds, ready to be spent as an input.

Conclusion

We have taken a look at the ledger for the Cardano blockchain. We have looked at basic transactions, the unspent transaction output (UTXO) model popularized by bitcoin, validation with addresses and public keys, and finally introduced the basics of smart contracts and how their on-chain components can be understood as state machines. That said, we have also skipped over some features of the ledger, such as multiple assets and staking, because I believe that they do not affect the substance of the EUTXO model and can be understood separately if desired. I hope this helps!

If this were a YouTube channel, I would ask you to smash the like button and click subscribe. Oh well. I guess I can ask you to leave comments below, though.

]]>I invite you to submit your paper to the 7th Workshop on Reactive and Event-based Languages and Systems (REBLS) in November 2020 in Chicago! I am on the program committee, though unfortunately, I probably won’t be able to attend.

Call for Papers

7th Workshop on Reactive and Event-based Languages and Systems (REBLS 2020)

co-located with the SPLASH Conference

Chicago, Illinois, USA

Sun 15 - Fri 20 November 2020

Important dates

Submission Deadline: 24 Jul 2020 21 Aug 2020.

Author Notification: 24 Aug 2020 18 Sep 2020.

Camera Ready Deadline: 5 Sep 2020 9 Oct 2020.

Introduction

Reactive programming and event-based programming are two closely related programming styles that are becoming more important with the ever increasing requirement for applications to run on the web or on mobile devices, and the advent of advanced High-Performance Computing (HPC) technology.

A number of publications on middleware and language design – so-called reactive and event-based languages and systems (REBLS) – have already seen the light, but the field still raises several questions. For example, the interaction with mainstream language concepts is poorly understood, implementation technology is still lacking, and modularity mechanisms remain largely unexplored. Moreover, large applications are still to be developed, and, consequently, patterns and tools for developing large reactive applications are still in their infancy.

This workshop will gather researchers in reactive and event-based languages and systems. The goal of the workshop is to exchange new technical research results and to better define the field by developing taxonomies and discussing overviews of the existing work.

We welcome all submissions on reactive programming, functional reactive programming, and event- and aspect- oriented systems, including but not limited to:

Language design, implementation, runtime systems, program analysis, software metrics, patterns and benchmarks.

Formal models for reactive and event-based programming.

Study of the paradigm: interaction of reactive and event-based programming with existing language features such as object-oriented programming, pure functional programming, mutable state, concurrency.

Modularity and abstraction mechanisms in large systems.

Advanced event systems, event quantification, event composition, aspect-oriented programming for reactive applications.

Functional Reactive Programming (FRP), self-adjusting computation and incremental computing.

Synchronous languages, modeling real-time systems, safety-critical reactive and embedded systems.

Applications, case studies that show the efficacy of reactive programming.

Empirical studies that motivate further research in the field.

Patterns and best-practices.

Related fields, such as complex event processing, reactive data structures, view maintenance, constraint-based languages, and their integration with reactive programming.

Implementation technology, language runtimes, virtual machine support, compilers.

IDEs, Tools.

The format of the workshop is that of a mini-conference. Participants can present their work in slots of 30 mins with Q&A included. Because of the declarative nature of reactive programs, it is often hard to understand their semantics just by looking at the code. We therefore also encourage authors to use their slots for presenting their work based on live demos.

Submission

REBLS encourages submissions of two types of papers:

Full papers: papers that describe complete research results. These papers will be published in the ACM digital library.

In-progress papers: papers that have the potential of triggering an interesting discussion at the workshop or present new ideas that require further systematic investigation. These papers will not be published in the ACM digital library.

Format:

Submissions should use the ACM SIGPLAN Conference acmart Format with the two-column, sigplan Subformat, 10 point font, using Biolinum as sans-serif font and Libertine as serif font. All submissions should be in PDF format. If you use LaTeX or Word, please use the ACM SIGPLAN acmart Templates.

The page https://www.sigplan.org/Resources/Author/#acmart-format contains instructions for authors, and a package that includes an example file acmart-sigplan.tex.

Authors are required to explicitly specify the type of paper in the submission (i.e., full paper, in-progress paper).

Full papers can be up to 12 pages in length, excluding references. In-progress papers can be up to 6 pages, excluding references.

Instructions for the Authors:

Papers should be submitted through: https://rebls20.hotcrp.com/

For fairness reasons, all submitted papers should conform to the formatting instructions. Submissions that violate these instructions will be summarily rejected.

Program Committee members are allowed to submit papers, but their papers will be held to a higher standard.

Papers must describe unpublished work that is not currently submitted for publication elsewhere as described by SIGPLAN’s Republication Policy (https://www.sigplan.org/Resources/Policies/Republication). Submitters should also be aware of ACM’s Policy and Procedures on Plagiarism.

All submissions are expected to comply with the ACM Policies for Authorship that are detailed at https://www.acm.org/publications/authors/information-for-authors.

Program Committee

Ivan Perez (PC Chair; NIA)

Alan Jeffrey, Mozilla Research.

Christiaan Baaij, QBayLogic.

César Sánchez, IMDEA Software.

Daniel Winograd-Cort, Target Corp.

Edward Amsden, Black River Software, LLC.

Guerric Chupin, University of Nottingham.

Heinrich Apfelmus.

Jonathan Thaler, University of Applied Sciences Vorarlberg.

Louis Mandel, IBM Research.

Manuel Bärenz, sonnen eServices GmbH.

Marc Pouzet, Université Pierre et Marie Curie.

Mark Santolucito, University of Yale.

Neil Sculthorpe, University of Nottingham Trent.

Noemi Rodrigues, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro.

Oleksandra Bulgakova, Sukhomlynsky Mykolaiv National University.

Patrick Bahr, University of Copenhagen.

Takuo Watanabe, Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Tetsuo Kamina, Oita University.

Tom Van Cutsem, Nokia Bell Labs.

Yoshiki Ohshima, HARC / Y Combinator Research.

Organizing Committee

Guido Salvaneschi, TU Darmstadt, Germany.

Wolfgang De Meuter, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium.

Patrick Eugster, Universita della Svizzera Italiana, Switzerland.

Francisco Sant’Anna, Rio de Janeiro State University, Brazil.

Lukasz Ziarek, SUNY Buffalo, United States.

HyperHaskell

— the strongly hyped Haskell interpreter —

version 0.2.1.0

HyperHaskell is a graphical Haskell interpreter (REPL), not unlike GHCi, but hopefully more awesome. You use worksheets to enter expressions and evaluate them. Results are displayed using HTML.

HyperHaskell is intended to be easy to install. It is cross-platform and should run on Linux, Mac and Windows. That said, the binary distribution is currently only built for Mac. Help is appreciated!

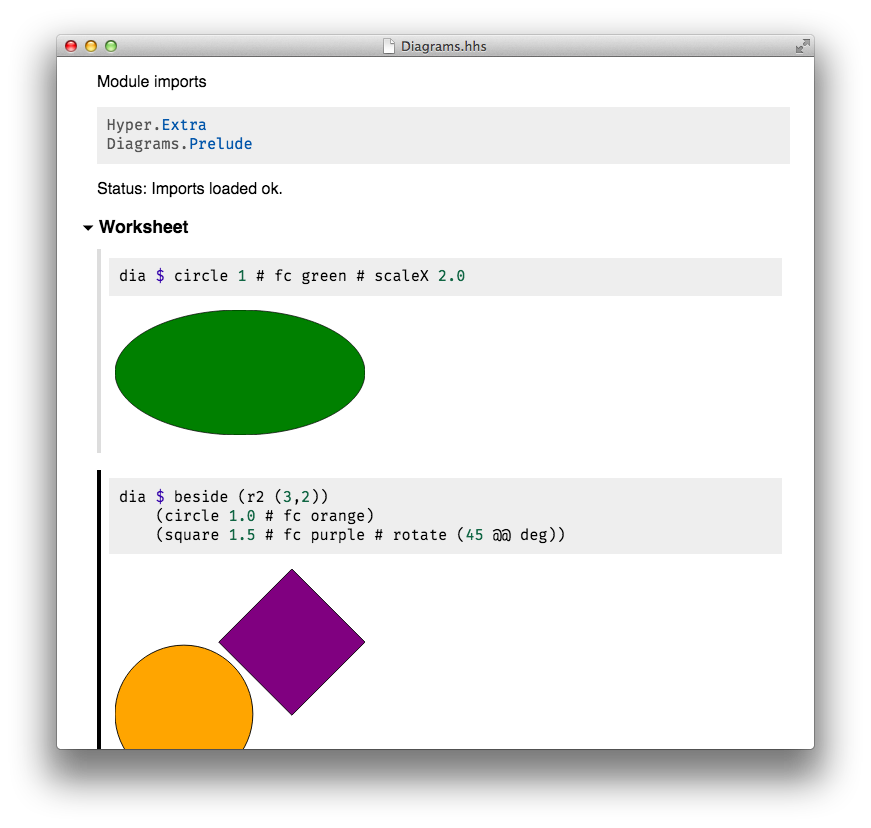

HyperHaskell’s main attraction is a Display class that supersedes the good old Show class. The result looks like this:

Version 0.2.1.0 supports HTML output, binding variables, text cells and GHC language extensions.

For more on HyperHaskell, see its project page on Github.

(EDITED 07 Aug 2018): Related projects that I know of:

- IHaskell — a Haskell kernel for Jupyter

- Haskell for Mac

- haskell.do

Unfortunately, IHaskell has a reputation for being difficult to install, since it depends on Jupyter. Also, I don’t think the integration of Jupyter with the local Desktop environment and file system is particularly great. Haskell for Mac is partially proprietary and Mac only. Hence this new effort.

]]>BOB is the forum for developers, architects and builders to explore technologies beyond the mainstream and to discover the best tools available today for building software.

I gave a talk on functional reactive programming; slides and videos are available.

I particularly liked the talk by Andres Löh on the Servant library, which allows you to scaffold a REST API entirely on the type level, and the talk by Stefan Wehr on the Swift language by Apple, which showed that functional programming already has become mainstream.

]]>This is essentially a maintenance release that fixes an important type mistake. Atze van der Ploeg has kindly pointed out to me that the switchB and switchE combinators need to be in the Moment monad

switchB :: Behavior a -> Event (Behavior a) -> Moment (Behavior a)

switchE :: Event (Event a) -> Moment (Event a)This is necessary to make their efficient implementation match the semantics.

Apart from that, I have mainly improved the API documentation, adding graphical figures to visualize the main types and adding an introduction to recursion in FRP. Atze has also contributed a simplified implementation of the model semantics, it should now be much easier to digest and understand. Thanks!

The full changelog can be found in the repository. Happy hacking!

]]>bytestring library, which is currently at version 0.10.6.0.

Every now and then, however, a library author feels that his work has reached the level of completion that he originally envisioned before embarking on the unexpectedly long and perilous journey of actually building the library. Today is such a day. I am very pleased to announce the release of version 1.0 of my reactive-banana library on hackage!

As of now, reactive-banana is a mature library for functional reactive programming (FRP) that supports first-class Events and Behaviors, continuous time, dynamic event switching, push-based performance characteristics and garbage collection.

As planned, the API has changed significantly between the versions 0.9 and 1.0. The major changes are:

Dynamic event switching has become much easier to use. On the other hand, this means that all operations that depend on the previous history, like

accumEorstepperare now required to be in theMomentmonad.Events may no longer contain occurrences that are simultaneous. This is mainly a stylistic choice, but I think it makes the API simpler and makes simultaneity more explicit.

If you have been using the sodium FRP library, note that Stephen Blackheath has deprecated the Haskell variant of sodium so that he can focus on his upcoming FRP book and on the sodium ports for other languages. The APIs for sodium and reactive-banana 1.0 are very similar, porting should be straightforward.

Thanks to Markus Barenhoff and Luite Stegeman, reactive-banana 1.0 now also works with GHCJS. If it doesn’t, in particular due to premature garbage collection, please report any offending programs.

Of course, the library will continue to evolve in the future, but I think that it now has a proper foundation.

Now, go forth and program functional reactively!

]]>Since its early iterations (version 0.2), the goal of reactive-banana has been to provide an efficient push-based implementation of functional reactive programming (FRP) that uses (a variation of) the continuous-time semantics as pioneered by Conal Elliott and Paul Hudak. Don’t worry, this will stay that way. The planned API changes may be radical, but they are not meant to change the direction of the library.

I intend to make two major changes:

The API for dynamic event switching will be changed to use a monadic approach, and will become more similar to that of the sodium FRP library. Feedback that I have received indicates that the current approach using phantom types is just too unwieldy.

The type

Event awill be changed to only allow a single event occurrence per moment, rather than multiple simultaneous occurrences. In other words, the types in the moduleReactive.Banana.Experimental.Calmwill become the new default.

These changes are not entirely cast in stone yet, they are still open for discussion. If you have an opinion on these matters, please do not hesitate to write a comment here, send me an email or to join the discussion on github on the monadic API!

The new API is not without precedent: I have already implemented a similar design in my threepenny-gui library. It works pretty well there and nobody complained, so I have good reason to believe that everything will be fine.

Still, for completeness, I want to summarize the rationale for these changes in the following sections.

Dynamic Event Switching

One major impediment for early implementations of FRP was the problem of so-called time leaks. The key insight to solving this problem was to realize that the problem was inherent to the FRP API itself and can only be solved by restricting certain types. The first solution with first-class events (i.e. not arrowized FRP) that I know is from an article by Gergeley Patai [pdf].

In particular, the essential insight is that any FRP API which includes the functions

accumB :: a -> Event (a -> a) -> Behavior a

switchB :: Behavior a -> Event (Behavior a) -> Behavior awith exactly these types is always leaky. The first combinator accumulates a value similar to scanl, whereas the second combinator switches between different behaviors – that’s why it’s called “dynamic event switching”. A more detailed explanation of the switchB combinator can be found in a previous blog post.

One solution the problem is to put the result of accumB into a monad which indicates that the result of the accumulation depends on the “starting time” of the event. The combinators now have the types

accumB :: a -> Event (a -> a) -> Moment (Behavior a)

switchB :: Behavior a -> Event (Behavior a) -> Behavior aThis was the aforementioned proposal by Gergely and has been implemented for some time in the sodium FRP library.

A second solution, which was inspired by an article by Wolfgang Jeltsch [pdf], is to introduce a phantom type to keep track of the starting time. This idea can be expanded to be equally expressive as the monadic approach. The combinators become

accumB :: a -> Event t (a -> a) -> Behavior t a

switchB :: Behavior t a

-> Event t (forall s. Moment s (Behavior s a)

-> Behavior t aNote that the accumB combinator keeps its simple, non-monadic form, but the type of switchB now uses an impredicative type. Moreover, there is a new type Moment t a, which tags a value of type a with a time t. This is the approach that I had chosen to implement in reactive-banana.

There is also a more recent proposal by Atze van der Ploeg and Koen Claessen [pdf], which dissects the accumB function into other, more primitive combinators and attributes the time leak to one of the parts. But it essentially ends up with a monadic API as well, i.e. the first of the two mentioned alternatives for restricting the API.

When implementing reactive-banana, I intentionally decided to try out the second alternative, simply in order to explore a region of the design space that sodium did not. With the feedback that people have sent me over the years, I feel that now is a good time to assess whether this region is worth staying in or whether it’s better to leave.

The main disadvantage of the phantom type approach is that it relies not just on rank-n types, but also on impredicative polymorphism, for which GHC has only poor support. To make it work, we need to wrap the quantified type in a new data type, like this

newtype AnyMoment f a = AnyMoment (forall t. Moment t (f t a))Note that we also have to parametrize over a type constructor f, so that we are able to write the type of switchB as

switchB :: forall t a.

Behavior t a

-> Event t (AnyMoment Behavior a)

-> Behavior t aUnfortunately, wrapping and unwrapping the AnyMoment constructor and getting the “forall”s right can be fairly tricky, rather tedious, outright confusing, or all three of it. As Oliver Charles puts it in an email to me:

Right now you’re required to provide an

AnyMoment, which in turn means you have totrim, and then you need aFrameworksMoment, and then anexecute, and then you’ve forgotten what you were donig! :-)

Another disadvantage is that the phantom type t “taints” every abstraction that a library user may want to build on top of Event and Behavior. For instance, image a GUI widget were some aspects are modeled by a Behavior. Then, the type of the widget will have to include a phantom parameter t that indicates the time at which the widget was created. Ugh.

On the other hand, the main advantage of the phantom type approach is that the accumB combinator can keep its simple non-monadic type. Library users who don’t care much about higher-order combinators like switchB are not required to learn about the Moment monad. This may be especially useful for beginners.

However, in my experience, when using FRP, even though the first-order API can carry you quite far, at some point you will invariably end up in a situation where the expressivitiy of dynamic event switching is absolutely necessary. For instance, this happens when you want to manage a dynamic collection of widgets, as demonstrated by the BarTab.hs example for the reactive-banana-wx library. The initial advantage for beginners evaporates quickly when faced with managing impredicative polymorphism.

In the end, to fully explore the potential of FRP, I think it is important to make dynamic event switching as painless as possible. That’s why I think that switching to the monadic approach is a good idea.

Simultaneous event occurences

The second change is probably less controversial, but also breaks backward compatibility.

The API includes a combinator for merging two event streams,

union :: Event a -> Event a -> Event aIf we think of Event as a list of values with timestamps, Event a = [(Time,a)], this combinator works like this:

union ((timex,x):xs) ((timey,y):ys)

| timex < timey = (timex,x) : union xs ((timey,y):ys)

| timex > timey = (timey,y) : union ((timex,x):xs) yss

| timex == timey = ??But what happens if the two streams have event occurrences that happen at the same time?

Before answering this question, one might try to argue that simultaneous event occurrences are very unlikely. This is true for external events like mouse movement or key presses, but not true at all for “internal” events, i.e. events derived from other events. For instance, the event e and the event fmap (+1) e certainly have simultaneous occurrences.

In fact, reasoning about the order in which simultaneous occurrences of “internal” events should be processed is one of the key difficulties of programming graphical user interfaces. In response to a timer event, should one first draw the interface and then update the internal state, or should one do it the other way round? The order in which state is updated can be very important, and the goal of FRP should be to highlight this difficulty whenever necessary.

In the old semantics (reactive-banana versions 0.2 to 0.9), using union to merge two event streams with simultaneous occurrences would result in an event stream where some occurrences may happen at the same time. They are still ordered, but carry the same timestamp. In other words, for a stream of events

e :: Event a

e = [(t1,a1), (t2,a2), …]it was possible that some timestamps coincide, for example t1 == t2. The occurrences are still ordered from left to right, though.

In the new semantics, all event occurrences are required to have different timestamps. In order to ensure this, the union combinator will be removed entirely and substituted by a combinator

unionWith f :: (a -> a -> a) -> Event a -> Event a -> Event a

unionWith f ((timex,x):xs) ((timey,y):ys)

| timex < timey = (timex,x) : union xs ((timey,y):ys)

| timex > timey = (timey,y) : union ((timex,x):xs) yss

| timex == timey = (timex,f x y) : union xs yswhere the first argument gives an explicit prescription for how simultaneous events are to be merged.

The main advantage of the new semantics is that it simplifies the API. For instance, with the old semantics, we also needed two combinators

collect :: Event a -> Event [a]

spill :: Event [a] -> Event ato collect simultaneous occurrences within an event stream. This is no longer necessary with the new semantics.

Another example is the following: Imagine that we have an input event e :: Event Int whose values are numbers, and we want to create an event that sums all the numbers. In the old semantics with multiple simultaneous events, the event and behavior defined as

bsum :: Behavior Int

esum :: Event Int

esum = accumE 0 ((+) <@> e)

bsum = stepper 0 esumare different from those defined by

bsum = accumB 0 ((+) <@> e)

esum = (+) <$> bsum <@ eThe reason is that accumE will take into account simultaneous occurrences, but the behavior bsum will not change until after the current moment in time. With the new semantics, both snippets are equal, and accumE can be expressed in terms of accumB.

The main disadvantage of the new semantics is that the programmer has to think more explicitly about the issue of simultaneity when merging event streams. But I have argued above that this is actually a good thing.

In the end, I think that removing simultaneous occurrences in a single event stream and emphasizing the unionWith combinator is a good idea. If required, s/he can always use an explicit list type Event [a] to handle these situations.

(It just occurred to me that maybe a type class instance

instance Monoid a => Monoid (Event a)could give us the best of both worlds.)

This summarizes my rationale for these major and backward incompatible API changes. As always, I appreciate your comments!

]]>