by David J. Lobina

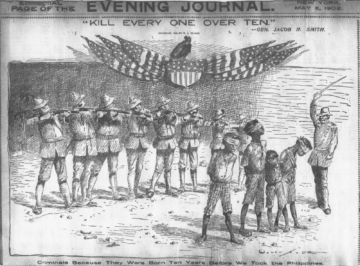

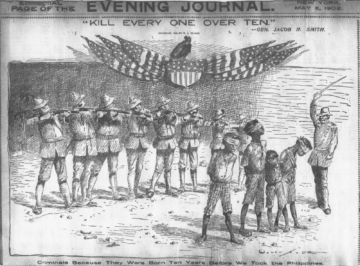

In a previous post, I joked that one of the most annoying things about living in an American world is the cultural hegemony that US soft power sort-of imposes everywhere. In that piece, I was concerned with the connotations that political concepts such as liberalism and libertarianism receive in US commentary, as these meanings vary to how these terms have been traditionally understood in Europe, where they originated, and some shifting of meaning has taken place in European discourse recently because of American influence, especially, as ever, in the UK (similarly for fascism, and even worse, sadly; see here). In the event, I did note in the article (endnote 1) that I was joking: the worst thing about living in an American world is US imperialism, with all the violence that derives therefrom.

More recently, in a series of posts on the legacy of Francisco Franco (last here), the Spanish dictator who provoked a civil war and then ruled Spain for close to 40 years, I argued that Franco’s actual legacy is the staggering number of dead people he left behind, many of whom were executed and buried in mass graves, their remains unlocated to this day.

Putting these two strands together, and in the context of the recent, blatant violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and the kidnapping of its head of state by US forces, I couldn’t help but feel that the human cost of the raid was not being discussed enough in most commentary. Yes, there are many important ramifications and some interesting discussions out there regarding previous US interventions in the region (here and here), the mostly meek response of US media (here), or the role of Venezuelan oil in all this (here), but one issue is usually mentioned only in passing: more than 50 people lost their lives in the raid, many of whom were simply doing their job, and some were in fact just bystanders (here and here).

And so I thought that instead of adding to contemporary commentary and write about this or that political aspect of the raid, I would this time post a list of conflicts the US has been involved with since the second world war, along with the number of people killed in these conflicts. Read more »

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

We sometimes say that someone is living in the past, but it seems to me that the past lives in us. It lives in our houses; it lies all around us. As I write this, I’m sitting on the couch under two blankets crocheted by my grandmother, who was born around the turn of the 20th century. The laptop sits on a folded blanket that came from Mexico via a friend years ago. And that’s just the surface layer. My closets and file cabinets are also full of the past.

We sometimes say that someone is living in the past, but it seems to me that the past lives in us. It lives in our houses; it lies all around us. As I write this, I’m sitting on the couch under two blankets crocheted by my grandmother, who was born around the turn of the 20th century. The laptop sits on a folded blanket that came from Mexico via a friend years ago. And that’s just the surface layer. My closets and file cabinets are also full of the past.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. January, 2026.

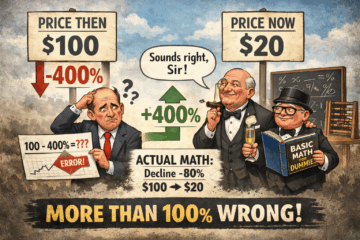

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. January, 2026. Oy. Where to start? Let me begin with a recent abuse involving percentages. Trump’s absurd claims about price declines of more than 100% have elicited a lot of well-deserved derision. How could someone with an undergraduate degree in business from Wharton make these mathematically impossible claims?

Oy. Where to start? Let me begin with a recent abuse involving percentages. Trump’s absurd claims about price declines of more than 100% have elicited a lot of well-deserved derision. How could someone with an undergraduate degree in business from Wharton make these mathematically impossible claims? In almost every medical school in the world, there is a cupboard—or a quiet back room—full of bones. The skulls are numbered, the femurs stacked like firewood, the ribs threaded onto metal wire. Officially, they are “teaching aids”. Unofficially, they are the remains of actual lives, reduced to objects that can be ordered from a catalogue.

In almost every medical school in the world, there is a cupboard—or a quiet back room—full of bones. The skulls are numbered, the femurs stacked like firewood, the ribs threaded onto metal wire. Officially, they are “teaching aids”. Unofficially, they are the remains of actual lives, reduced to objects that can be ordered from a catalogue. 2025 was a good year for books.

2025 was a good year for books.