| CARVIEW |

Why INIT HELLO even happened is a subject for another time. Today’s subject is also not specifically about the building where it was held, but now’s a good time as any to tell you about it if you’ve never heard of System Source.

System Source is a business sort of business that handles training and IT and does all that office sort of stuff, but it also contains a computer museum, which itself is composed of multiple other museums. It’s like a fun museum turducken.

INIT HELLO was organized rather quickly, months to be specific, and it’s a miracle it all came together so well. This was, in part, not only the effort of the organizers, the folks who dropped some cash to float the costs, and a lot of volunteer labor throwing in – it’s also because the owner of System Source opened doors for an odd, unproven, lumpy event to take place.

That kindness led to a fun little conversation at some point when it turned out the owner of System Source was also on the board of the Vintage Computer Festival, which I’d written about semi-recently.

He and I chatted a little about this and that related to the VCF organization, my interactions with it, and the law of unintended consequences.

Thus, here we are.

While I continue to not attend Vintage Computer Festivals, and my interactions along various lines tells me the inter-organizational structure of the place is prone to misunderstandings and confusion, you shouldn’t punish the attending exhibitors, who do some of the finest work in retrocomputing and have no say or agency in matters beyond their table space.

For many people who harbor love of old machines and concepts, and who are filled with a wish to share their knowledge or collections with a sympathetic and engaged audience, the Vintage Computer Festivals held throughout the United States (and soon Canada) are often their sole opportunity to connect with old (and new) fans of their efforts.

Some of my finest interactions with people who have gone above and beyond to maintain and present technology have happened at VCF-related events – and while I won’t drag them into a sort of paradoxical Jason Scott-attention Devil’s Bargain by mentioning them, I’ll say that I’ve enjoyed their smiles and their conversations. Solid, good people, doing good things: A brimming joy and wonder about these expensive machines converted to toys and educational entertainment about the world they came from.

A good display of computer history doesn’t just happen – it can represent years of careful collecting, precision layout of signs and wiring and explanatory diagrams, and then hauling (at great distance, personal expense, and time) into a waiting empty space at various venues. VCF is not the only place that offers this, of course; but even as one of a fabric of opportunities, it is a not insignificant percentage of the chances these exhibitors have in a given year to meet future fans and collaborators.

Interpersonal conflict is my personal candy, and while it’s a delightful jaunt when the gears turn just so and a truly well-crafted flaming arrow can be directed into unsuspecting machinery, I’ve been led to believe that my essays far exceeded their mark and have caused financial distress. Without diving too deep into research for that claim, I’ll simply say that it would truly make me sad to have some of these families and individuals, just trying to show their home-baked technological wares, be left standing in an underattended hallway or chamber hoping for an audience that seems less populated each passing year.

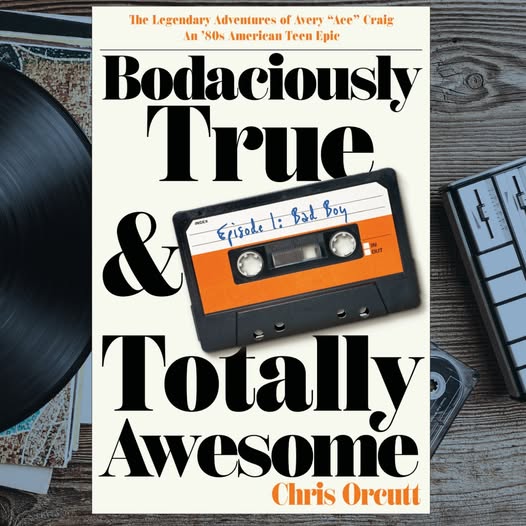

]]>When we want to amuse ourselves, Chris Orcutt and I calculate out how long we’ve been friends, because the number is massive by most standards and it’s one of our little consistencies through our individual, chaotic lives. The number as of this writing is 43 years.

We are no-holds-barred fans of each other, and of our divergent goals and efforts in our paths. The bias is deep-seated and profound, palpable really. If you’re building up a court case against one of us, the other will not join you, and in fact you may find yourself with a spoon in your neck before the proposal gets out of your mouth. We are bonded and we back each other up.

This round, it’s my turn.

After being literally across the street from the World Trade Center on 9/11/2001, Chris recalibrated his life and career away from (very good) copywriting for businesses and CEOs, and took his previous years as a journalist, and became a full-time novelist, which was always his dream. He’s been doing it ever since.

And not just doing it – excelling at it. His books have sold very well, and it is possible to grab them immediately. That is, a significant amount of times, he has set off on a book writing project, spent the years doing the drafts, refining, editing, and then publishing it where others can enjoy it. His books exist. The ratings are excellent. The boy can write.

In his 40s, he found himself at a bit of a crossroads.

He’d written some solid mystery novels, a number of anthologies, and more. And while writing is everything from frustrating to solid-state euphoria, and creating books was his heart and soul, he didn’t want to go into the ground having made “a bunch of books”.

He wanted to make something substantial. Something you could have an opinion on, but that opinion couldn’t include the words “slight” or “okay”. A piece of work you had to at least take off your hat for a moment and mutter “mother of god” before either reaching for it, or backing away. An accomplishment.

Ten years later, he’s there.

This is ten years of no nights out, scant visits to family and friends and events, and long walks with Dashiell the Dog in parks and trails working out the endless puzzles of a nine-part novel series.

Nine parts! Nearly two million words! I struggle to give context to this sort of dedication to the project. Chris has estimated he’s spent at least 30,000 hours over the decade writing the novel, but we all know you have to count all the time considering possibilities, discarding approaches, suddenly realizing you’ve been swimming laps but were deep in a scene.

I prefer percentages: Chris has spent 20 percent of his life on this project.

If nothing else, acknowledge the effort. Coming to the end of a project this massive, this involved, this concentrated diamond of goal, stands among very few who set off on such a journey. He fuckin’ did it.

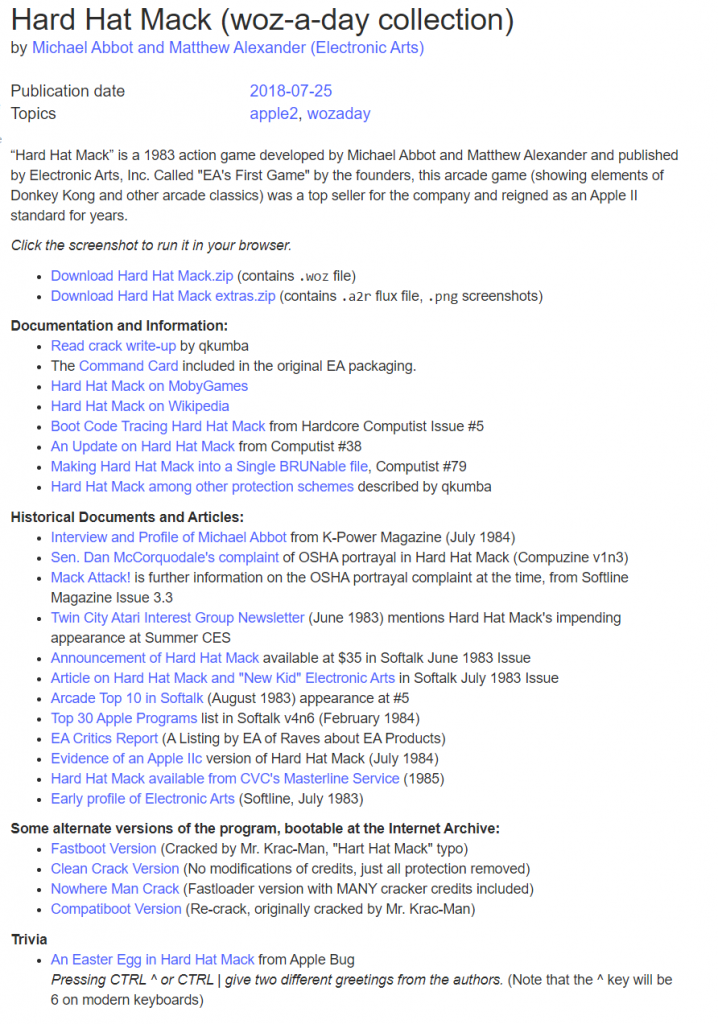

I will refrain from describing the depths Chris went to in making his novel, which takes place in the 1980s, as accurately as possible. But one small overlap with me naturally sticks in my mind:

In the book, his main character Avery Craig writes a letter on his Macintosh. Chris wanted the feel of the keyboard and the experience of a real Mac to guide his words, so he asked me, and I arranged, to have a vintage Mac, carrying case and all, available to use to make it authentic:

I respect the relentless hustle to do right by his project, to take the full walk around, to not guess but research and find out the true and real world he’s bringing together in this monument of printed pages.

Now, like Chris, you stand at a crossroads.

The nine-volume series begins to come out in 2026, with additional books to come out across a timeline. You can close this window and probably hear about the books coming out then, and buy the first one, fall in love with the tale and tell a friend, or just enjoy them however you enjoy your books.

or.

You can help an author of authentic skill, who redirected his laser-like abilities away from churning out noir after romance after adventure tale, who worked on a truly gigantic project, what very well seems to be the first teen epic, properly promote and prepare this series for a proper literary lifespan.

You see, books suffer.

Not from being able to get somewhere after being printed, to sell some copies after being put on shelves or online, to get a bit of an audience after being out there….

…they suffer because they need promotion and support and a hundred little costs to break through the membrane of life’s distractions and cacaphony to gain a foothold in universal awareness.

This novel series is coming out – that’s not a question. It’s done, getting the kind of polish as it goes to printers and gets distributed through various platforms. It’s going to happen. That’s not what Chris and his family and I are asking of you.

We’re asking for people to contribute support to the campaign and efforts to give this book series the respect and treatment it deserves.

The goal is simple: NO CHEAPING OUT.

No using clip art and basic fonts for the covers. No relying on a couple notes here and there to let people know about the project. No avoiding spending money on talented people in the field of promotion and awareness. The plan, evocatively described on their fundraising page, and the result of years of planning, is to put the same sweat equity into the promotion and sale of this project as was put into its creation, year in and year out, up to this point. The plan, taking up a whole wall of a hallway in their home, is to spend five years on this, half of what it took to make the series in the first place.

And to do that, they need funding. People who are looking to drop not just a few bucks expecting a printed series in their mailbox or inbox in a year or so…. but people who go to the page the Orcutts set up, read the pitch and plan, and said “OK, now this is quality.” People who will, impulsively or after great amounts of thought, put serious coin in the Orcutts’ hands with the understanding they are using this money to bring the all-important promotion of this life’s work to the greatest audience they can find.

The Orcutts will be doing this, what they promise on their page. I will personally refund your money if they don’t. That’s how much I believe in them.

They’ve described the whole project in detail. They’ve laid out the plan. They’ve set out all the good silverware and they’re inviting you in to see what they’re going to do. You either will go “well, uh, see you when it’s out” or you understand, from a person who himself has spent years and years on projects, that now is the time to be shockingly generous. Your contribution will have great ramifications for what this series can do to bring attention to what it is.

Just do it. Tell them I sent you.

]]>Let’s do a little of both.

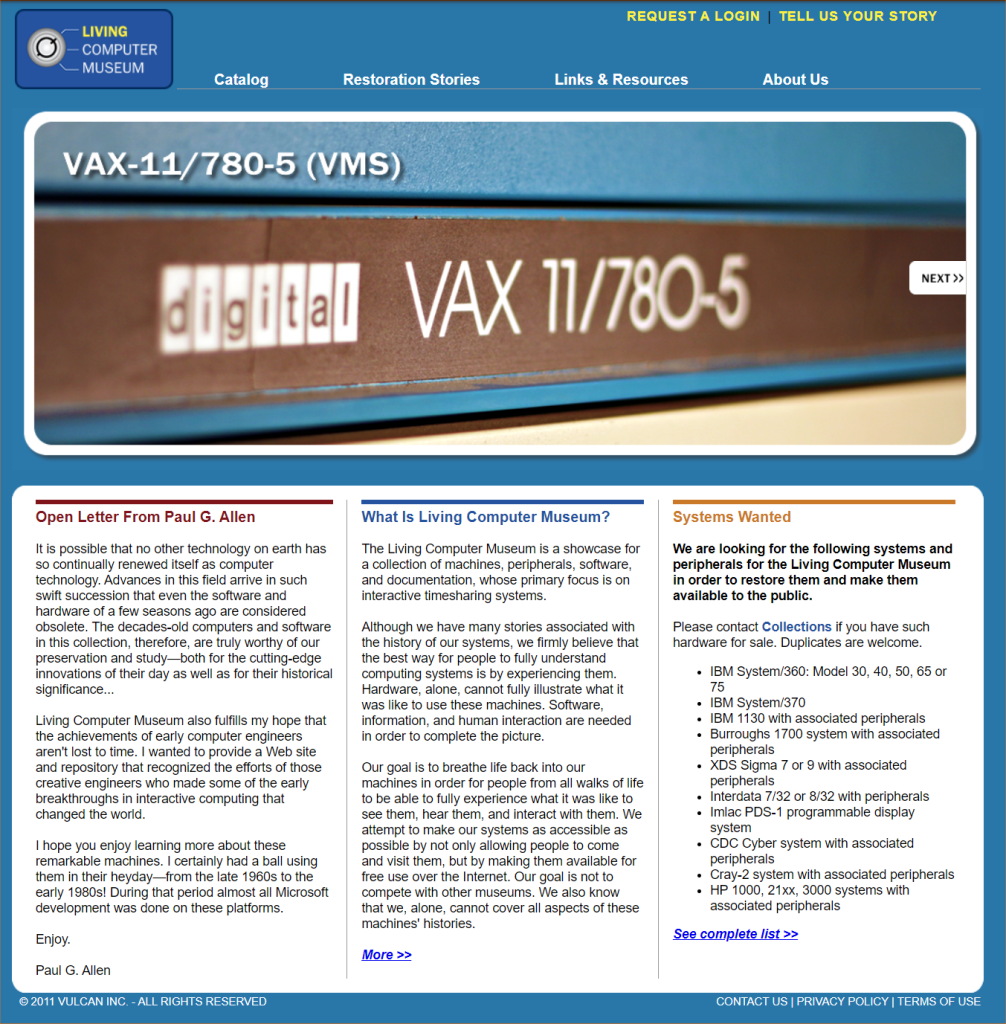

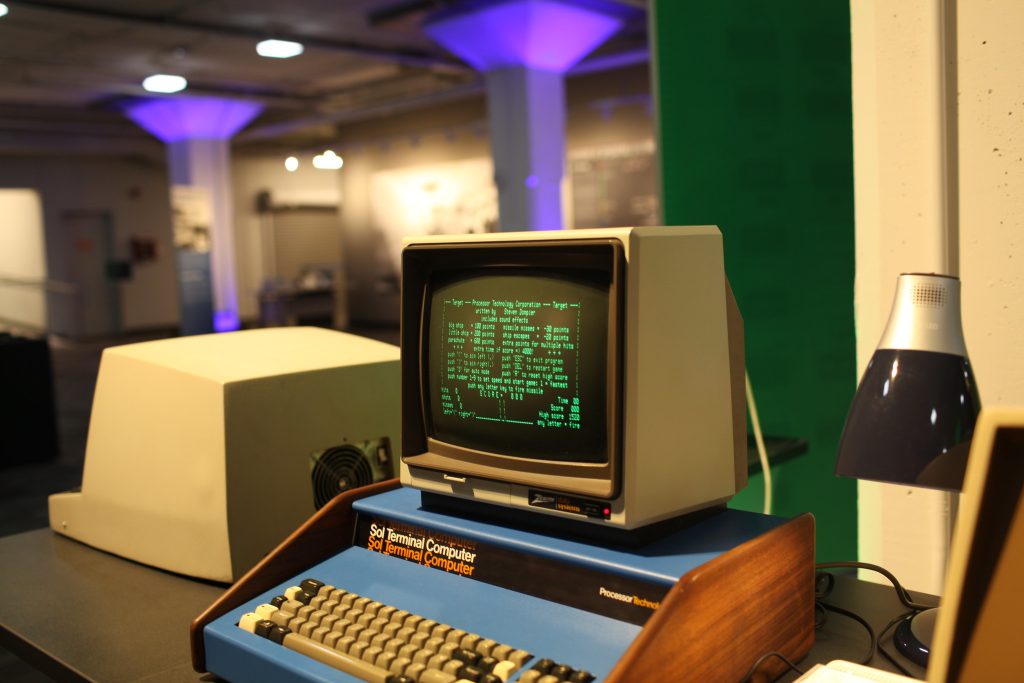

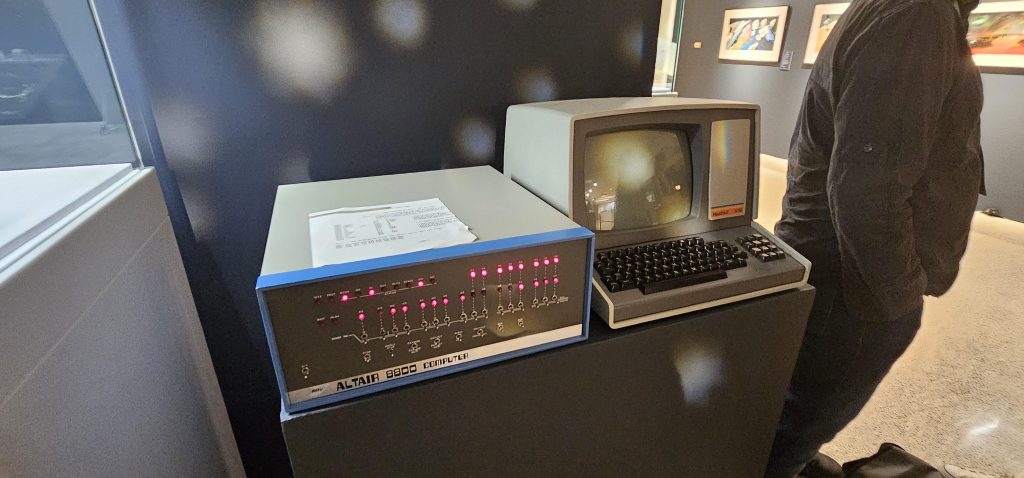

The proposition of the Living Computer Museum was initially simple, and rather amusing in a Slashdot-baity sort of way: You could apply to get an account on a real, actual ancient Mainframe hooked up to the Internet, which meant you could literally connect into real, actual ancient hardware. I assure you that to a segment of the population, this is an irresistible proposition. It’s also, ultimately, one that even the most ardent fans of “how it was” will leaf away from, because mainframes are their own wacky old world, like using a taffy-pull hook, and appeal on a day-to-day basis to a relative handful of die-hards.

But in 2011, the Living Computer Museum announced itself with the kind of slick webpage that promised computer history buffs a new wonderland.

There’s a lot to take in with this verbiage, but let’s keep going, for now.

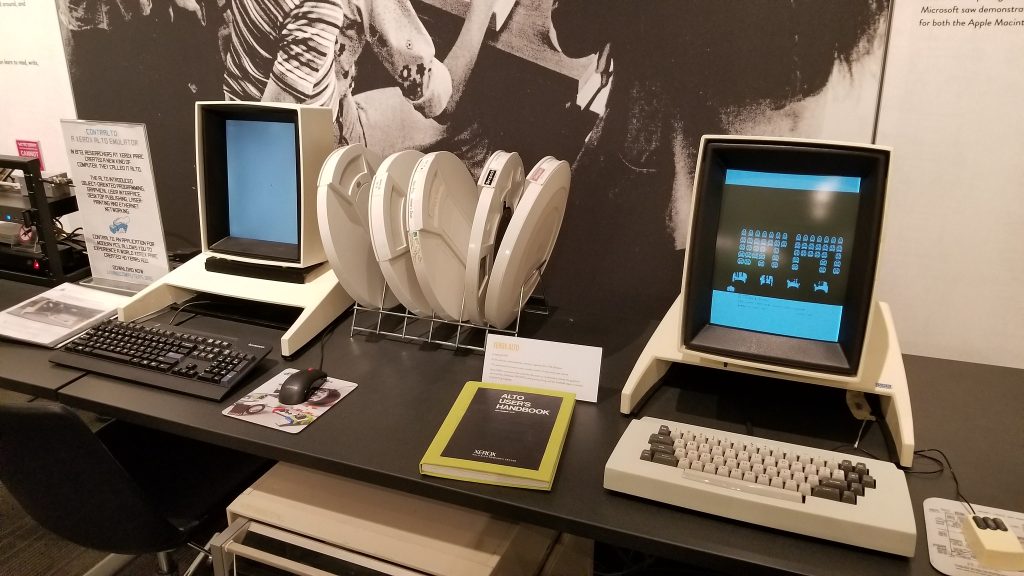

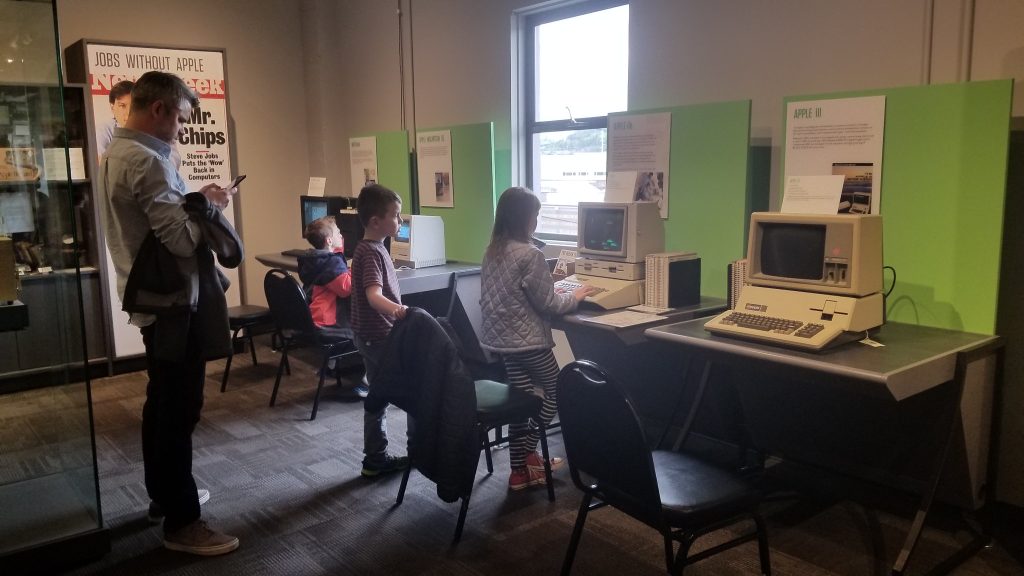

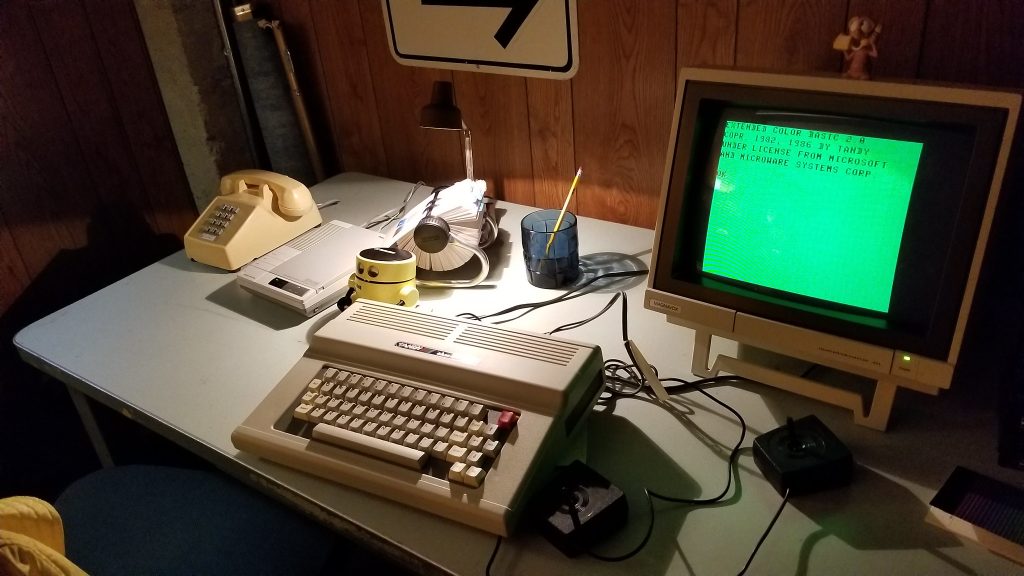

In 2012, the Living Computer Museum opened its actual, physical doors to the public in Seattle. A year later, I visited. It was rather nice. I got a grand and lovely tour by some very polite and friendly people, some of whom I’d known for years. The rooms, well appointed, well-lit, and in the case of the machine rooms, done to a sparkling arrangement, clamored for my attention and approval.

There were computer museums for years, decades before Living Computer Museum, scattered among the United States and the world. I’ve been to many of them – sometimes as an honored guest and backstage VIP, and sometimes just because I hastily read my “find me weirdo geek stuff” Google Maps results and negotiated public transit to walk into the door and walk around like a strutting mayor to see what’s what. In that pantheon, I would put LCM in the realm of “very well appointed, especially the mainframes” but not in the realm of “nobody, ever, has ever tried anything like this”. Just off the top of my head, the Computer History Museum in Mountain View has brought not just mainframes and historical computers back from oblivion, but hosted events in which their maintainers and figures have gotten a chance to get their stories on record.

Still, one couldn’t argue with it – the LCM was a solid new outpost in Telling Computer History, and it was on my shortlist of potential homes for materials I might donate in the future. I had a lovely conversation with a member of management about how they maintained functionality and also what their contingencies were for any sort of “endgame” that might befall the endeavor. He assured me they had storage aplenty, in the extremely unlikely event they had to face a closure. Ultimately I didn’t donate my materials there, simply because I found nearer geographic or mission-aligning homes.

My next, and it turns out last, major visit to the Living Computer Museum (outside of a few drive-bys) came in 2018, when I spoke at an event being held there. This gifted me with a chance to see how things had changed in 5 years, and how they had.

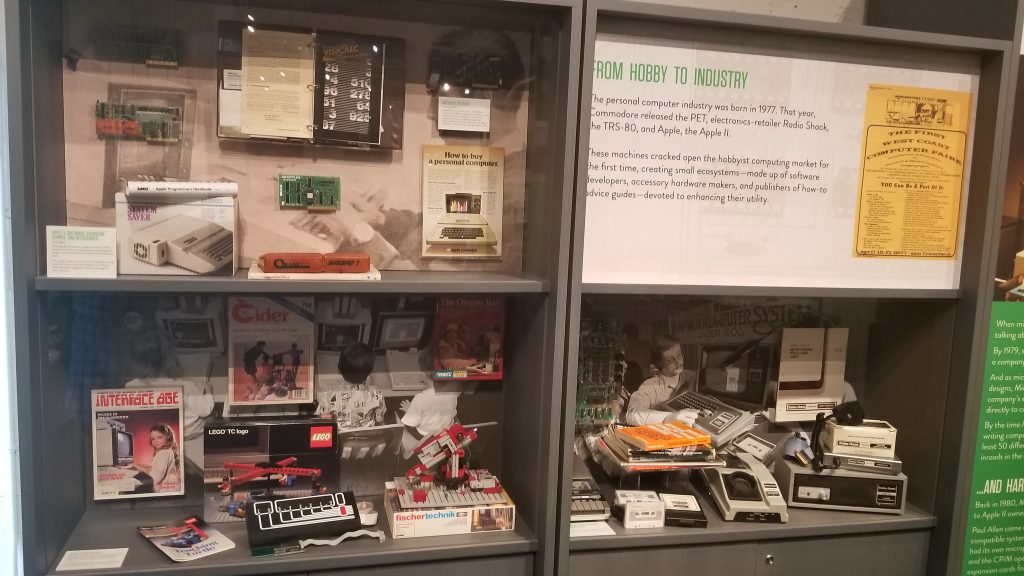

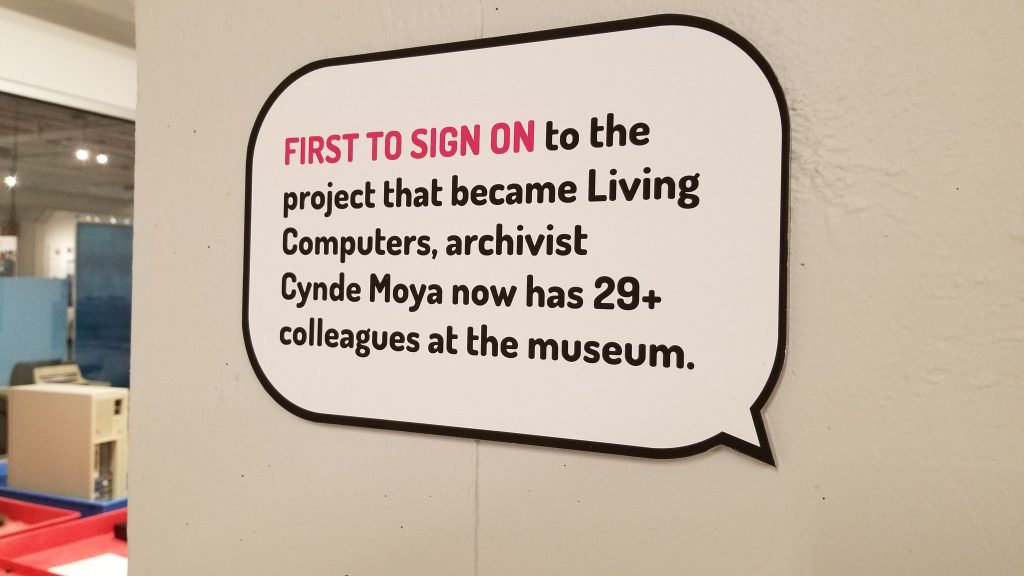

Here, then, was something approaching a dream. We had the display cases of technology and the clean carpets and cathedral ceilings of available space, filled not just with computers on desks but entire computer-related environments: classroom, arcade, basement, that showed youngsters what sort of context these computers had lived in. I met Cynde Moya, who had been described to me years earlier as a hard-nosed disciplined caretaker of the materials, and who turned out to be everything they said except hard-nosed – a truly dear overseer of things physical within these walls.

This was April 2018. I lived in the world I live all the time: full of hope, equally full of expectation of doom. But hope was winning.

In October of 2018, Paul Allen was dead.

I suppose everyone has opinions on billionaries, their position in the world, what they represent, and maybe almost everyone has, spoken or unspoken, an awareness that the level of money billions represents disengages you, whether you think so or not, from humanity.

I mean, sure, they cry, laugh, stub their toe, wonder if that’s rain coming, get surprised when the killer’s revealed in a well-done noir thriller. But there’s this cloud of wealth that is ever-present and depending on how it is maintained, or manifested, it slowly bleaches out the edges of living until you realize there is a shocking serenity in their countenance, a noise-cancelling blur that surrounds them, because there are always people whose job is to be aware of them and whose job is to ensure the serenity is maintained.

And there’s the sheer spending power of a billion. I’m sure I could toss out a hundred funny examples of the sheer numerical force of a billion dollars. For example, you could have someone buy a 2025 Subaru Outback, itself the rough amount on the lower end (nationally) of a Domino’s Pizza General Manager’s yearly salary before taxes, and push it into a lake. Taking Christmas and the pusher’s birthday off, to run through a billion dollars of Subaru Outbacks would take you 61 solid years.

But that’s not even very accurate. During that 61 years of pushing Subaru Outbacks into a lake (in Neutral, of course, I’m not a monster), the remaining amount of the money not being spent to purchase lake-bound outbacks would actually be MORE. THAN. A. BILLION. You would actually be richer than you started, if you invested it in even the most brain-dead obvious multi-percent-a-year funds, or left it in any bank. That’s because time and space warp around money.

So do people.

In 2018, after getting cancer in 2009 and 1982, Allen got it again, and this third (public) bout with it ended him, at age 65. His net worth at the time of his demise is the kind that publications who make it their business to will guess at, and the guess sat around $20 billion. Everyone has kind of accepted that, but it’s not really important if it’s $50, $15 or $5 billion. It’s a lot of money.

With his billions, over the decades, Allen owned or partly owned three sports teams, at least 10 companies ranging from airplanes, scientific research, media, and space flight. He owned massive real estate, a movie theater, threw buckets of cash at schools, the arts, and ultimately, a few museums.

To manage it all, he had a company whose purpose was to manage the money, because he wasn’t going to do it himself. The company’s name is Vulcan, Inc. Even after divestment and shutdown after Allen’s death, it has 700 employees. It is one of the largest trusts in the world. It is also now called Vale Group, but I’m going to keep calling it Vulcan.

Vulcan, a company whose job is to manage money and where that goes, is still quite intensely active as an entity, even with Paul Allen’s death. His sister, Jody Allen, chairs the organization she co-founded with her brother in 1986. This company is absolutely gargantuan in its scope and range, and remember, it is a company that just manages a ton of money – that’s the company’s entire purpose.

I wish to take a short moment to not demonize Jody Allen. As the remaining sibling in charge of this company, functionally working through her brother’s holdings, many of which she clearly had no interest or extant position in, and doing so for six years and counting, can’t be anything else than the strangest mixture of pain and endless complication. The $20 billion she’s now in charge of might soften the blow, but likely not by much.

And I apologize for the whiplash here. I’m not overly interested in going down the paths of describing what Jody should be doing, or what her responsibilities are. I am not privy to whatever deep law and lore and functions buried within Vulcan’s iron heart she and her army of people are dealing with, that six years later they are still slowly divesting organizations. I know she has personally called for cullings but I am not informed about the deepest depths of how the aspects of these billions function.

I want to refocus to the fact that Vulcan is divesting itself of the Living Computer Museum.

I want to refocus to the fact that the Living Computer Museum was never a museum.

Look, don’t jump down my throat about this. I’m as shocked as you are.

I didn’t get some inkling from the phone call I had a decade before about potentially donating to Living Computer Museum. I don’t have some spidey-sense about failure or darkness – I just see it everywhere in everything and I treat every day like it’s the one before they find a lump.

If, before it closed, you had made me stand in the center of the LCM and answer whether it was a museum, I’d have happily held up my top hot and shouted “Why yes! One of the finest in all the realms!”

And for all I’d know, it was a museum. There’s no laws on what a thing can call itself regarding being a museum, exhibition, tour, or display. It’s against the law to take money to attend the museum and you get led to an empty lot, sure. But if something has the vestements and affectation of a museum, and you see the big sign saying Museum out front and you go in and there’s displays and staff and events and meetings, you would certainly think it was a museum.

Turns out it wasn’t.

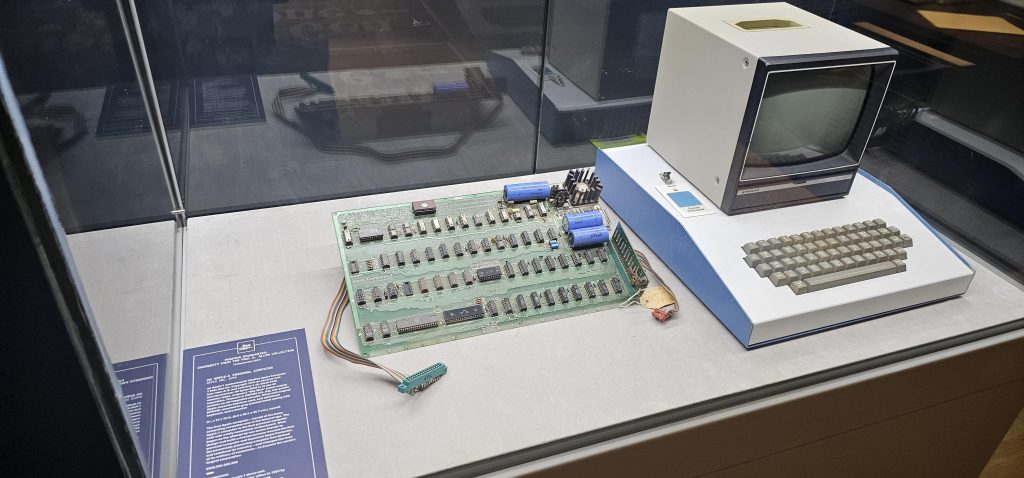

The auction house Christie’s announced it was doing an auction of some of the best portions of Paul Allen’s estate, first with art, and now it would be selling off technology. To fans and studiers of the Living Computer Museum, these items seemed familiar – some of them were on display in the museum.

I found out that some of these to-be-auctioned items would be on display near where I live, so I hopped in my car, parked grandiosely illegally in front of the building, and let myself in.

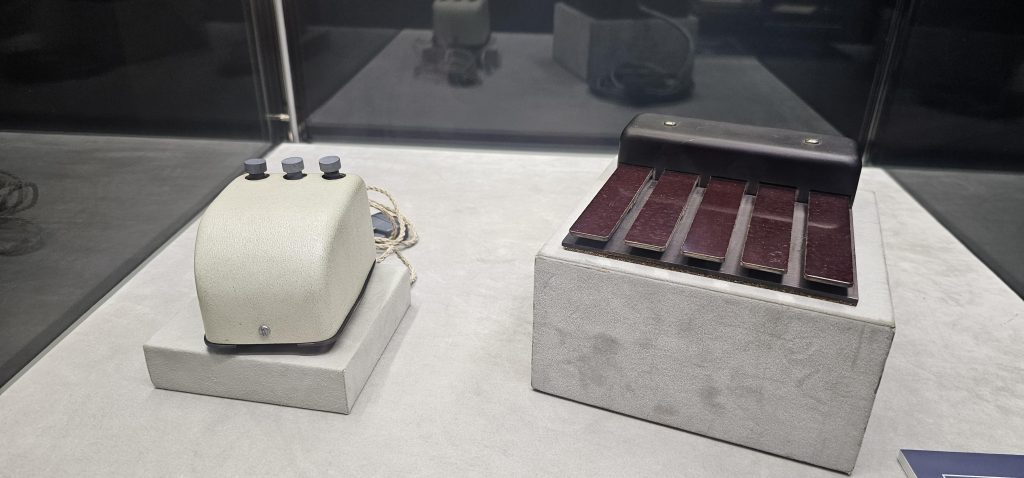

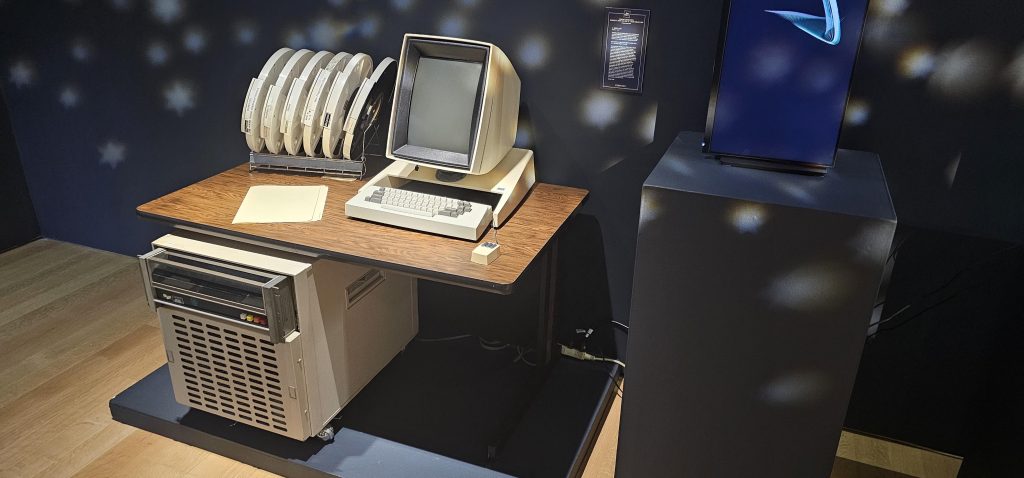

On display were all sorts of computer history of the “early major days” variety, ranging from a Xerox Star to an Englebart Mouse and even a Pac-Man machine. All had descriptions, all were held out where you could get very near them assuming the guard wasn’t watching too closely, and all of it with a starry-eyed disco-ball aesthetic indicating you were in a space lounge.

So yes, items from the museum were now going to be sold to the highest bidder in a few months. These were some of them, and likely there would be more.

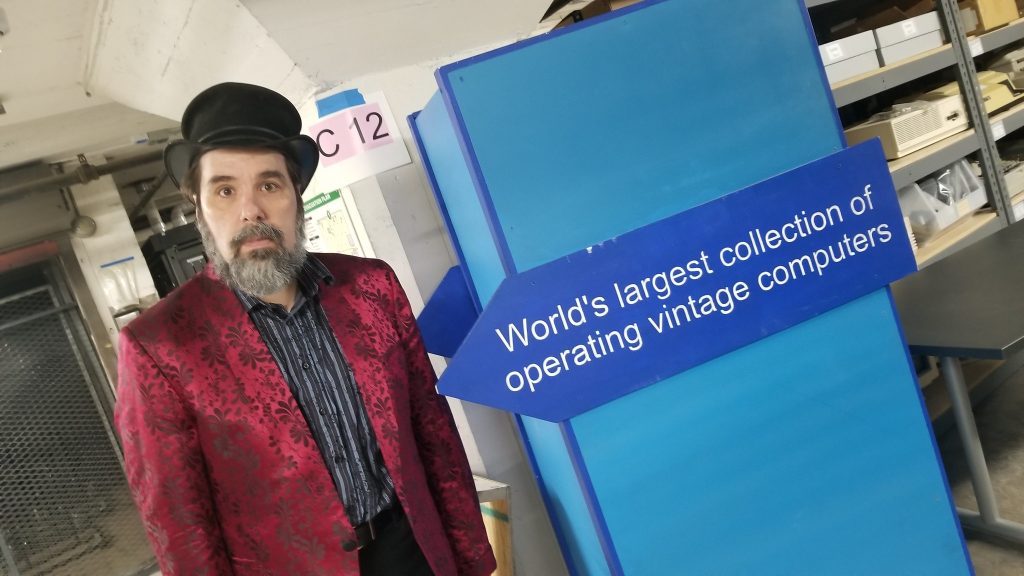

And then, among the relics, I found Stephen Jones.

Stephen Jones and I go a long way back. He was interviewed by me for the BBS Documentary in 2003. So that’s 20 years I’ve known the guy. At our interview session, he showed me his PXL-2000 and his Delorean, both of which I can assure you are high-end geek possessions of the time. And I found his conversation style charming, and his passion for technical subjects perfect for my film.

Stephen’s primary non-profit endeavor, the SDF Public Access UNIX system, was in full swing back then, and is still around now. “Do cool computer things, but don’t try to turn everything into a financial instrument” is not the motto, but it should be. It represents, to me, a lovely ideal of a truly living computer community, incorporating new technology as it expresses itself being something neat, or worth bringing in. Laptop Amish, if you’re stretching around for an anology, which you shouldn’t be. It’s a computer club. And he’s a big part of it.

He was also my initial “in” for the dish on the now-not-so-Living Computer Museum. We’d gone a long way, and here we were, in Christie’s in New York City, standing among offered-for-auction pieces of a gone billionaire’s museum, and maybe we needed to talk in detail, so we did. And I grilled him.

Let’s go back to that initial 2011 announcement page on the Living Computers Museum website, before it was officially an open building.

In the light of its piecemeal disassembly, a lot of this writing hits different. Here’s what I’ve picked up, from Stephen and others, and which I assume for some readers will be new information.

First, this was always intended to be an actual, non-profit, independent/independent-subsidiary museum. It never became that. It is not that. At best, the Living Computer Museum was a billionaire’s (sorry, multi-billionaire’s) collection of computers and technology.

Think of it another way: Jay Leno has a very famous garage that has many wonderful cars and vehicles in it. It is currently, as of this writing, run by a very competent manager named Bernard Juchli, who has been keeping the collection in line for over 20 years. That is, to say, that Leno has a massive collection of cars, competent staff to take care of it, facilities to show them (he has had a number of documentaries and television shows about the garage) and he could probably even open it to the public for an admission price. But you would be hard pressed to call it a “museum” in any sense beyond “it is a display people see videos about”.

As per the request in that 2011 webpage grab, people donated many computers and pieces of history to go into the museum. They expected, no doubt, that they and their children and their childen’s children could stop by displays and point and talk about the family connection to these items.

That was a mirage, a misunderstanding.

This was Paul’s collection of computers, aided by friends and fans. It was always that. The Living Computer Museum, it turns out, cost millions, over ten million a year, to operate as it was set up, and it never came close to making that amount of income from door sales and t-shirts. It never came close to even figuring out how it would.

It’s perhaps not surprising this misunderstanding could happen, and with what felt like all the time in the world, a mere five years and change of being open to the public might have seemed like a mere revving up for the grand plan of what would come next. But nothing came next. It was a collection you could walk through in a really, really nice display case.

And now it’s time to sell the collection.

Before I end up on a huge rant about what it means to be a museum, let me at least give you some relative good news.

The current rough plan is that the big-ticket items, like this Apple I, will be sold at auction. They’ll make beaucoup bucks, go into private collections or maybe even other institutions, and that’s that for the headliners. But that leaves a lot of other stuff.

SDF has a rough plan to raise funds and digitize software, documentation and other related items that are not part of these big-ticket sales (which will be relatively few) so that unique bits of history that are not headline-grabbing trinkets will, potentially, have a chance at being shared with the public.

And I’ve stepped into it. I’ve offered to take software and documentation and store it at the Internet Archive, and of course to work with SDF on ways to digitize/rip/scan materials and, also, host them at the Internet Archive.

It’s all preliminary, but my card is in the hat. Things are not going to be discarded, if I have anything to do with it. A lot can change, and we’ve already seen expectation vs. outcome with this whole experience, but rest assured, I’ve at least tried to provide one last safety net for the kind of history that easily finds itself gone because nobody steps forward. Internet Archive has stepped forward. Stay tuned to see how that works out.

But you know, what did we learn here? What did we actually come away with in the realm of lessons or teachings about what issues this whole mishegaas has churned up?

I have found, perhaps not to my surprise, that a few people in my orbit are displeased I have punched the dead billionaire, ostensibly about all the good the dead billionaire did. But I wish to point out the dead billionaire did give away all that money and yet still had 20 billion dollars at the end, money that went off and did not do as many nice things as the money given away. So much contributed, tax-free, and yet there’s even more. Perhaps this is not the best place to point out that every billionaire is, in many ways, a failure of society, but maybe we can put a pin in it when we have our first trillionaire, assuming that criticizing a trillionaire is not made illegal at that soonish juncture.

I did have some people say, in not so many words, that of course the Living Computer Museum would collapse once its Master of the House was no longer in charge, and I would take this time to point out that Gordon Bell, co-founder of the Computer History Museum, passed on in May of 2024 and yet the Computer History Museum lives and breathes in his absence. It wasn’t a hard problem.

It’s easy to call me ungrateful, but my ungratefulness comes from the narrative people weave near the power of money, like those myths formed around gods and devils, to explain why things are how they are. I appreciate life and its little whorls and eddies that capture us by surprise and we sink or swim. I do not appreciate acting like someone spending a lot of money on something that slightly amuses them earns them the greatest respect. Especially when, as I do now, I walk among a literal army of people working to clean up the mess left behind, after their march to oblivion.

]]>It flows fast, so fast that when you look away and look back it’s in many ways an entirely different river, not just a slightly different one. It used to be blue with an occasional brown or black. Nowadays, it’s basically brown and black and a signficant amount of it lets off a slow-moving steam that you’re positive causes cancer in 99% of living things. You used to swim in this river, but now you generally don’t, and by “generally don’t” you mean “never”.

Instead your interactions are thus:

You have an occasional cinderblock you wouldn’t feel comfortable throwing in the tiny lagoon you mostly hang out in, or the notably smaller (and cleaner, and calmer) rivers you swim in these days.

So, you walk down to the bank of the river of lost dreams and sulfuric nightmares and throw that cinderblock as far as you can to see what sort of massive splash it causes, and what horrors lurking underneath its surface will temporarily breach to snap and bite and thrash until it goes back to a flowing, nauseating shit-river.

Anyway, that’s how I tweet.

I wrote up this massive framing entry to prepare to write a meaningful weblog entry about what we’re all calling AI but is just “throwing so many GPUs at the problem that our inherent need to find fellow souls in the darkness does the rest”. I call it “Algorithmic Intensity” and started the journey of writing a contextual entry to give my thoughts considering 40 plus years with computers, hype cycles and expectations of technology.

I ended up not doing it, primarily because a lot of the same effort that took writing weblog material and doing presentations is mostly taken up by The Podcast. The amount of paying subscribers has dwindled over the six (!) years it’s been recording, but those folks do help with my medical bills and other costs, so they’re kind of getting the best of me, and definitely the best of my efforts. I mean, don’t worry, I like you too, errant reader from beyond the screen – but those folks keep my office rented, my doctors’ visits stress-from-bills-free and allow me not play Old Yeller with my domains.

This balancing act, of doing free and by some definitions altruistic sharing of information with the nitty gritty costs of material goods and services and vendors is the absolute classic conundrum, and lies at the heart of many an Internet Presence. One of my credoes when I’m talking to people who want to do some sort of endeavor is that Every Person Is At Least Five People when it regards to ongoing concerns that produce work on a persistent basis. Someone blasting out an epic every half-decade or so aside, if you find a “person” doing “a lot”, the chances are that that person has other people, friends or collaborators or employees, who are doing some of the lifting. To consider those people lone wolves is usually a fallacy, and therefore there are somewhat-hidden costs or measures of contribution that are leading to the thing you just … get to have.

I’ll save some comments on AI for the end. Let’s get to why I’m writing this at all.

The cinderblock I threw into the Twitter crap-stream was a comment that Google had made yet another user interface/experience shift, and in my opinion, this took a number of skirmishes the company has been waging against the idea of the world wide web and moved, intentionally or not, into outright war.

The actual content of the thread is sort of irrelevant to me; but just to satisfy curiousity, I was essentially indicating this: Google forcing, by default, to a majority of users over time to see a generated summary of the output of the aggregate browsed sets of material out on the internet, especially at the low-quality they’re doing it, is a fundamental shift in the implied social contract that allowed search engines to gain the utility they have. I did it in a handful of crappy tweets and was literally in between some Gyoza and my Sushi lunch and when I noticed sometime later that I was getting tons of notifications (I don’t have twitter as a client on my phone anymore, so I didn’t get buzzing or beeps or anything) and when I ran the analytics that the account has, the numbers were fucking ridiculous:

“My child has been kidnapped; if you see a grey Toyota with red stripes, call the police” deserves those kinds of numbers. So does “I, person responsible for ten years for this beloved product or franchise, was just summarily fired for unknown reasons”.

“I think Google made a boo-boo” absolutely does not.

But justice doesn’t exist for this sort of lottery, and I watched the flaming pyre of attention gain millions of (partial) humans and tens of thousands of “Engagements”, and I have a general rule about all this.

All this to say that once we’re up to this level of froth, whatever’s coming out of it has the stretched-almost-transparent feel of an already flimsy nylon sock over a 55-gallon drum of toxic waste. Twitter used to be amusingly knockabout in the variance of Opinion Tourists who would stop by for a quick hit; now it’s just a series of either “didn’t read” or “I am stopping by because the only way I feel anymore is the resistance from sticking a blade against your rib cage”.

On my cold read of the actual responses with actual words, they are best summarized as:

- You say AI-generated summaries are a step too far from Google. I do not like previous Google steps.

- It’s actually all great and you are old. (Someone called me a Boomer, but heaven’s sakes, I’m Gen X)

- Everything is terrible and this is terrible and you are terrible

- Herp Derp Dorp Duh (Rough translation)

Let’s waste the time with what I was bringing up, in a slightly cogent fashion:

For sure, Google has both innovated some amazing accesses to realms of information (Maps) and often provided a (usually bought from someone else) product that many might find useful (Mail) and has done services which take advantage of their well-funded technology to provide a nominal benefit to the world (the 8.8.8.8 DNS server). They’ve also, in their quest to make the web “better”, leveraged their near-monopoly on browser engines and search engines to create “programs” and “policies” that are little more than “make it better for Google” (AMP comes to mind, there’s many more).

Google’s constantly manipulation of web standards to suit their needs does not make them special; they’re just the assholes with a hand on the steering wheel for now. And like previous holders of this title, they’ve poisoned, cajoled, forced, ignored and ripped their way through standards, potential competitors and independent voices and figures along the way.

Picking out any specific sin (or “hustle”, as shallow techbros like to call it) is usually a Sisyphean task, but in the actual thing I was referring to in my tweet cinderblock, it was a program that Google implemented where an AI “summary” is showing up in a growing set of mobile and desktop instances (customers), completely choking off anything one might point to. I called this a declared war against the web. It is not the only war. It is not only warfare against the web. Picking it apart reveals chains linking to a thousand points of contention. I’d hoped to avoid AI discussion for some time but here we go.

I have lived through a variety of “revolutions” and hype cycles of said revolutions, and the fallout and resultant traces of same. I did a documentary about one. I enjoyed living through the others, although with time it’s been a case that I was often not old enough or given enough perspective to truly look down the sights of what was going on and derive a proper horror/entertainment from the various ups and downs.

And now, one version of a type of software that has been around for a long time is suddenly on everyone’s minds. It’s being used to make a variety of toys. A number of people are hooking those toys up to heart machines and bombs. And I’m fifty years old and I get to watch it all with a pleasant cola in my hand.

I’m profoundly cynical but I’m not generally apocalyptic. For me, what’s being called “Artificial Intelligence” and all the more reasonable non-anthropomorphizing terms is just a new nutty set of batch scripts, except this time folks are actually praying to them. That’s high comedy.

Also, my eyelids are growing heavy and I literally have to caffienate myself to keep talking about it. Fundamentally, there’s as much excitement for me in the “potential” of everything AI as there was for double-sided floppies, sub-$500 flatscreen televisions, console emulators, USB sticks, MiniDV cameras, and discount airflight. All of them enact change. All of them are logical innovation. All of them stayed, morphed, went. At no point in any of them did I have apoplexy or spiraling mental breakdowns. Life went on.

Regarding of “something should be done”, the point of my original planned weblog entry was to refer to the Aboveground as something some AI companies were doing – straddling that balance of “we are too new to be regulated or guided” and “it’s too late, we’re basically ungovernable”. My attitude is that Algorithmic Intensity should be punched in the crib, given a solid going over. I had a conversation with one AI person that “farm to table” tracing of the source material being trained on would be a must and that companies should be devising ways to provide that information. He said it was impossible. It is not impossible.

When I mess with this stuff (and I have accounts on a bunch of these services, that I mess around with), I have a fantastic time. I am doing all sorts of experiments and try-outs of the tech to see if it has uses for what I deal in, which is scads of information. My response continues to be, as it always has for something new, that setting the old stuff on fire to “force innovation” is a sign you are a world-class huckleberry. The main change in this particular round is I can’t remember a time we had so many people showing their whole and entire ass by saying “I can’t wait to fire ______ because this MAKESHITUP.BAT file is producing reasonably full sentences”. What a lovely tell. In my middle age, being able to have something go “beep” when a time-wasting numbnut has entered the chat is a golden algorithm, and the speed at which companies and individuals have been willing to throw everything out, reputation-wise, is a glorious moment.

Which brings me, again, to this specific Google situation.

There’s just no way the high-fructose syrup of the kind of answers these “smart agent” responses are giving in search engines will last. A number of people on Twitter told me that if a site could be summarized in 200 characters by this, they never deserved to exist anyway. Problem is, the 200 characters are NOT summarizing the site. It’s not even often good! It might get “better” but ultimately companies like this do not have the ability or skill to generate new creations or do helpful works – they can only remix and re-offer, buying out the same collections or licensing access. And if those terms are not good, they’re going to lose a lot of money buying back trust.

I don’t like writing about non-timeless things, but we are in a phase right now and that phase is both fleeting and extraordinarily entertaining to me. As I said to a friend recently,

“We get to be 50 and watching this all go down! Front row seats!”

How this all shakes out, what parts stick around and what snaps in half, is for luck and spite and challenge and response to decide. If the best people always won, our world would look and feel a lot different. But while the fireworks and trumpet blasts echo through the landscape, I’ll save a seat for you.

]]>I block. I block frequently, quickly, and across every single medium that consitutes “communication” in the contemporary era.

I’ve been doing it for well over a decade, but somewhere after my heart attack I upped the frequency and dropped the level at which the “block” action gets enacted. It is very, very easy to find yourself unable to directly communicate with me via the method I blocked you.

Why anyone would possibly care that I do this (beyond the people I block) is not entirely my responsibility, but I think there’s a point, so let’s keep going.

First, I’m rather easy to find and communicate with. I have many channels of ingress, from phone numbers and e-mails to social media and streaming. I do this mostly because I’m trying to be there when people have materials to donate to Internet Archive, or if they’re in distress and need to reach out to someone. Both these situations happen more than one might think. I appreciate both when they do, and do my best under the circumstances.

But the downside is that people can reach me very easily and all your instincts that there are spectacular counts of truly damaged individuals who have effortlessly acquired internet access and spray their damage around the world like some urine-filled lawn sprinker are, as I can personally attest, correct.

At some point, depending on how far back you have persisted online, there was this unspoken contract that you gave someone multiple bites of the apple to show how awful they were, under the theory that the first interaction was an inadvertently bad impression. That contract is no longer in effect. That’s a large contingency of folks gone; the masters of showing up in the middle of a conversation or communication, unbidden and unwanted, and dropping absolute bile into the stream. One strike and they’re out.

Occasionally, I even pre-block. I block people who, when I see them interacting with others, I have no overly powerful urge to envision ever being a part of their online lives. I suppose there’s some fundamental Fear of Missing Out that could be ginned up regarding them, that they might end up saying or doing something that I should know about, but I’ll let others tell me. There are a non-zero amount of times I’ve seen people say “Foobatz69 has a point” and I go look them up and I’ve blocked Foobatz69. Maybe I’ll peek in. I probably won’t.

Less obviously, it goes the other way too. In a notable amount of situations, I’ve blocked people because I recognize that I’m going to be the problem, that what I do and how I approach things are exactly the sort of activity that makes a given person or account go ballistic or switch to attack mode, so I save us both the trouble. I occasionally hear they’re confused. I do not seek to explain why. They continue to live a normal and happy life, and I continue along with mine.

So, why bring this all up?

Well, first, occasional this-and-that publicity has provided me with the ability to see discussions about myself in which a small number of blocked folks commiserated about the whole “Jason blocked me” situation and of course many have taken the Imagination Express to Injustice Town to describe a situation where I could possibly have come to the decision to block, and the general consensus will be some variation of a degredation of my mental health.

It’s quite the opposite. My mental health has never been better.

Outside of absolute buzzbomb cornhusks dropping corossive misery at every opportunity, there were a range of folks who I truly admired and respected who, upon my looking back retrospectively at our interactions across years, totally lacked warmth and friendliness from their position. Literally every response a vicious insult and somehow, I’d considered this a pleasant and comfortable dish to be served down the front of my tuxedo on common occasions. Their blockage is literally medication, a salve, an ointment. I’m free of my delusion that they are friends.

And again, there are folks who, I find, are going to be nothing but negative energy in my life, at a time when I am growing older and don’t see much need to throw my body and life into a deep dark well of irrelevant free-floating rage, never to be recovered or rewarded.

And you know? On at least a half-dozen occasions, which is more than any reasonable person should experience, I’ve had individuals who, upon being blocked and clearly indicated their presence and communication were unwelcome, proceed to track down and find every single communication channel still open to them and begin upping the energetic demands I explain myself. I’m talking chat systems, phone calls, e-mails from various addresses, and asking friends of mine who might still have contact with me to “put in a word” to “set the record straight”. In other words, I have entirely too many examples where people I had a bad feeling about have gone absolute full stalker mode, in a way that they would never imagine themselves as such, but absolutely are. On two of those six occasions, it happened physically.

None of those half-dozen are being unblocked. That was not the solution to the percieved issue.

I’m sharing this not for some sort of support plea, or to indicate I have a hard life. I have the mathematical opposite of a hard life.

I’m sharing it on the off-chance that someone reads this, realizes their relationship with someone or someones online is actually a massive negative energy drain, or rife with abuse, or simply a case of not realizing you’ve left a pathway to lightweight harassment that can do nothing but increase. If that’s the case, trust me. Block, block, block. Report and block. Mute and block. You will feel parts of your soul unclench that you didn’t previously understand were balled into tights fist of stress and simmering disaster. I’m involved in dozens, sometimes hundreds of interactions in a given week, and I do it. You should consider this your license to do it as well.

If this helps two people, it was worth it to discuss. And it’s already helped one, and that one is me.

]]>Naturally, as is the case when you post anything anywhere in public, I am called a liar. I’ll simply say that everything I describe in the blog entry happened. I contacted a VCF administrator and was told it was all disposed of, and that they kept the bins. I am fine with people claiming that disposal was not what happened, but this is what I was told, directly, in human words. The fact that I am seeing contradictory and confusing descriptions of what happened is not a checkmark destined for the Win column.

A few people have rushed to indicate that I need to be more careful describing “which” VCF entity is at fault. I am sad to report to them all that the Byzantine VCF structure of name licensing, geographic branding, and internal corporate entity is meaningless to anyone six inches away. You all know each other and you all interchangeably use nomenclature. If you are part of an organization that calls itself some form of “VCF” and need an opportunity to write a statement about how your organization in a solitary/separate entity and should be considered more worthy or ethical than others, feel absolutely free.

A small sliver of people were concerned I was saying that I was never going to go to any computer history conference or event again. I am a free person with the freedom to attend whatever is open to the public. As it stood, however, VCF East was the easiest event for me to attend, so it was where I saw people the most. A minor point is that I considered attendance a form of endorsement, but that is my own personal choice. The chances of me attending other events is, like death by cow, low but never zero.

The rest of the discussions I have seen from the blog entry, raging in the usual stages of social media and posting forums, have failed to require any further response or thought from me personally.

Finally, this is all relatively minor in terms of the work I do and projects I focus on, an event that brought me some fury but which has mostly played the part of filed under “life lessons”. I just got tired of having quiet inward emotion when I was reminded of the event, specifically when VCF announcements would pass by my screen, followed by nice folks asking if they would be seeing me at the event. Now I have made a statement, and rather than the beginning of a saga, I consider it the end of one. My conversations with people and organizations I shift materials to are much longer, much more involved, and with much more contingencies as a result of this event, and things are better for it.

Years ago, clearing out the Information Cube, I donated its contents to roughly 10 organizations, carefully splitting things up for the best home, as I’d been entrusted with these materials by many great folks who believed I’d make the right choices. Videogames went to the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment, books and many printed materials to the Internet Archive, piles of game-related magazines went to the Strong Museum of Play, multiple sets of Wired magazine went to a scanning group, and so on. This was a shipping container worth of material, so we are talking dozens and dozens of crates, received by trustworthy and great folks across the entire country.

Among these donations were a set of publications, mostly IEEE-related but with a few other sets of titles, to the Vintage Computer Federation, based in New Jersey. The donation was roughly this:

To make this donation, I paid for the containers, filled them, put many issues in bags, and then rented a truck to drive them the roughly 70 miles to the VCF headquarters in Wall, NJ. There I dropped them off and went home. This was roughly 2017.

A number of years later, I contacted the Vintage Computer Federation to ask how the magazines were doing, if they were part of a project, or if I needed to transfer them elsewhere.

I was told they tossed them out. Every one.

However, I was told, they had decided to keep the plastic boxes, and were making use of them.

As a result, I’ll state clearly: I have no intention of attending the Vintage Computer Festival or doing any sort of interaction with the VCF team again.

I’m mentioning this because I went to so many of the festivals, I know people would be expecting me to go, and I get mail every year looking forward to my attendance. I have indicated I would not be there, but not totally explained why. Now I have. I consider attendance to be an endorsement of this action, and I am fundamentally uninterested in whatever clumped-together set of words they might consider an apology. The concern is dead to me.

I also want to take this moment to clearly state that Evan Koblentz, the director of the Vintage Computer Federation for many years, who took the original donation, had absolutely no say or part in this pulping of historical magazines, having been driven out of the organization years before. Evan has always been a steel beam of dependable honesty and directness in all the years I’ve known him, which is bordering on decades at this point.

There’s not much else to say. Go if you want, but I won’t be there. Hopefully I will see some of the nice folks I know from the event in other contexts. Otherwise, it has been quite real, and they’re memories I won’t trash for their containers.

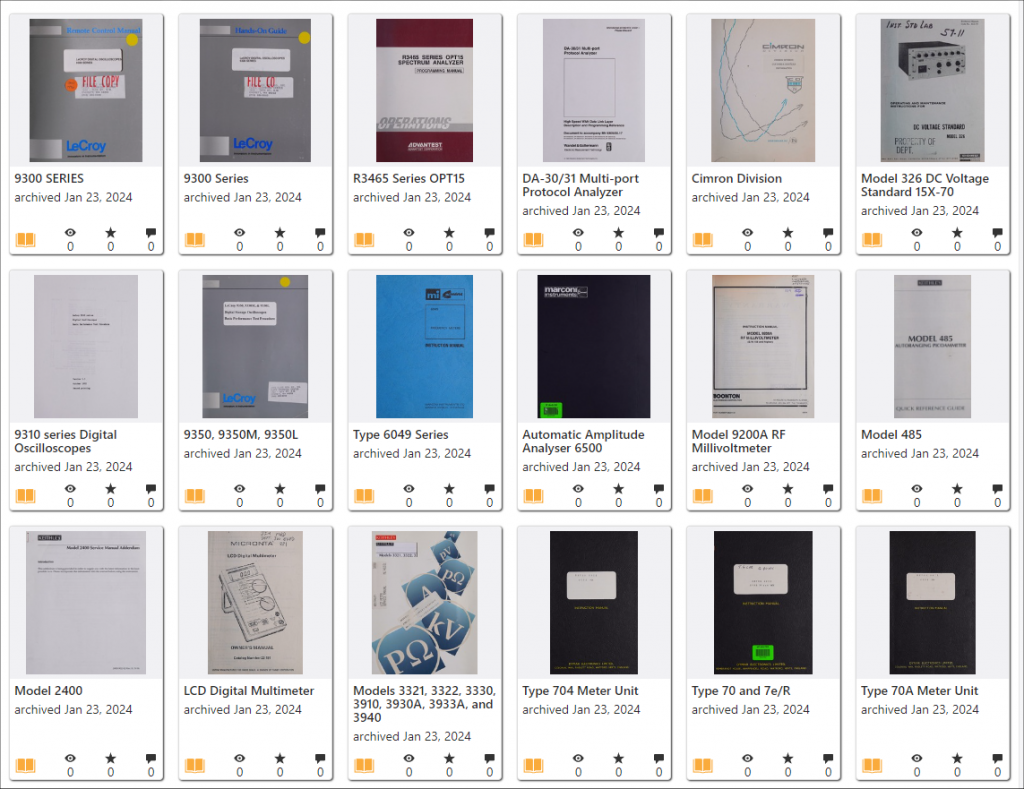

I’ve written so much about what is now called the Manuals Plus Collection. Let’s go find those:

- In Realtime: Saving 25,000 Manuals

- In Realtime: Prepping for the Transfer of 25,000 Manuals

- In Realtime: It Is Almost Halfway Done

- In Realtime: Day 2 Felt Like Week 4

- In Realtime: It Is Done

- A Small Dark Detour

- In Realtime: Post-Mortem

- A Little Bit of the Manuals

If you don’t want to walk those, I’ll make it simple: I got word in 2015 of a collection of manuals inside a business that was getting out of the business, and while a lot of well-meaning people talked a good game, they wanted to cherry-pick (people getting rid of stuff hate cherry-pickers), and I drove down to show I was serious, and after a week of work with MANY volunteers and contributors, we ended up with pallets of documentation inside boxes, numbering something like 50,000-60,000 manuals. (A rough estimate.)

Then they were stored in a storage unit. Then they were stored in a closed coffee house. Then they were transported to California. Then they were stored until last year, 2023.

Last year, a group called DLARC, doing digitizing and indexing projects around ham radio and radio technology, worked with me and the archive to sort out a few pallets of the manuals for products related to the history of radio/network technology, and off they went overseas to be scanned. And as of this month, the evaluated, professionally-scanned and available-to-the-world manuals are beginning to show up in this collection:

The Manuals Plus Collection

Like, it’s happening! It’s happening. It’s happening!

Like anything else open at Internet Archive, you can search the text contents (which are being automatically OCR-ed). You can download the original unformatted jp2 files in a zip. You can download a PDF generated from the jp2 files. You can read it online.

Either this is the first time you’ve heard of all this going on, or you’ve known about it and wondered whatever happened to that mass of manuals.

They’ve been kept in safekeeping, awaiting their moment. We reboxed them, and in fact, transporting them from MD to CA was the last major project I did before my heart attack. It might have been the last thing I ever did for the Archive! That would have been a pretty good way to go out.

But here, in 2024, the final stretch is going on.

And now, the pitch.

The group doing the digitizing does lots of digitizing for the Internet Archive. They are well-paid and legitimate professional contractors who are sent the items, and who do careful scanning to the best of the materials’ ability to provide access to the information, and then do quality checks, and then upload them. When they’re humming, they’re processing a pallet every couple of weeks (with lots of mitigating factors). They’re going to get through the four pallets sent to them from the DLARC sorting very quickly, in other words.

I’ve negotiated a situation where, if money is sent in, the remaining pallets that should be scanned can just be sent along without sorting them for DLARC funds, DLARC will fund any that happen to overlap with their mission, and the rest will just be done.

That’s if money is sent in.

How much money? We’re still working that number out. It’s going to be somewhere in the range of tens of thousands of dollars. So I’m looking for both big-ticket supporters (who can mail me at jason@textfiles.com) or individuals. In all cases, you’re just going to donate to the Internet Archive itself, which is at https://archive.org/donate and your donations are tax-deductible. Telling them you’re donating to support this project will help keep the project funded. (There’s a way to leave a comment, and if not, send me a note you did it and how much).

We’ve already sorted these things into pallets, and we know a subset of these (HP and Tektronix) are scanned elsewhere and don’t need to be specifically done this way. This leaves just the historically vital and informationally wonderful manuals dating from the 1940s through the 2000s. As they’re popping up, each one is a gift.

If we make less than we need to scan them all, then we’ll only scan up to where it’s paid for. I believe we can close it out, but if the interest/money isn’t there, then it isn’t there – fair enough. Browse the collection as it grows into thousands of manuals as it is and consider if you want to be part of all that. That’s definitely happening.

But what a happy ending it would be to push all these manuals through the process, and close it up. That’s why I’m popping up to talk about it, and why I hope you would consider contributing towards it, for a non-profit that deserves your support generally.

Meanwhile: It’s happening! It’s happening. It’s happening!!

]]>Computer Shopper was a hell of a magazine. I wrote a whole essay about it, which can be summarized as “this magazine got to be very large, very extensive, and probably served as the unofficial ‘bible’ of the state of hardware and software to the general public throughout the 1980s and 1990s.” While it was just a pleasant little computer tabloid when it started in 1979, it quickly grew to a page count that most reasonable people would define as “intimidating”.

In a world that saw hundreds of magazines and thousands of newsletters come and go about technology and computer-related subjects, Computer Shopper was its own thing entirely. Not only thick as a brick, but clearly opened to anyone who waved cash and covering vendors who were selling computer components down to the individual part level. You might have a good set of ads in PC Magazine but to browse over price lists of capacitors, power supplies and wiring, the massive monthly Computer Shopper issue was going to be your go-to.

There were two other aspects to Computer Shopper that has given it a halo of intrigue and positive memory: First, the paper was incredibly cheap, newspaper tabloid level by some eyes. This seeming disposability infers a weird sort of honesty about the advertising contents – it is what it is, it represents what the actual pricing is, and what’s actually available. The lack of pure slickness in the printing process was a baggage of “look, I’m lucky if we survive another month and this is the straight up price we’re offering” across the many hundreds of ads in a given issue.

But second, was the full-bore willingness to seemingly absorb anything computer adjacent into its pages. Pre-fab computers and commercially available software was listed inside, sure. But if you were selling tech clothing, clips, floppies, tapes, plugs, paper, switches and accessories… you had a home there as well. It gave a truly manic and freewheeling melee to the affair, and for those of us who wanted to know more than the standard 20-30 software packages everyone was buying, or to think about smacking together a bunch of parts to get a mutant-powerful system up and running, this was the place.

To a smaller set of us, the BBS Listings in the back were also a very notable aspect. BBS operators across all the spectrum of cliques and locations thought of Computer Shopper as the BBS yellow pages, the phone book of the online, for almost its entire run. You flipped to the back, found your area code or state, and downright eye-watering levels of BBS listings were waiting for you. Inaccurate? Sometimes. But a truly unique assemblage of what was.

That catches us all up to what Computer Shopper was. Like many print-based computer magazines, Computer Shopper grew in size into the many of hundreds of pages, some greater than 800. It thrived in the world before the World Wide Web took hold, and once you could do daily updates of parts and prices at various websites, the months-lag in printing schedule and the lack of responsiveness compared to websites made it lose curry, favor, and eventually pages. It died a quiet death in 2009, becoming a barely interesting site and then an uninteresting zombie.

Still, it was a heck of a run.

People often ask me the same basic questions regarding old computer history and access to it. One of them is to discuss potential holy grails, possibilities of where some effort might be afforded to acquire potentially lost information or artifacts before they’re gone.

A common go-to for me was Computer Shopper, because it’s a perfect storm of absolute fascination and completely intolerable amounts of barriers towards digitizing it into something readable online.

- It’s fantastically huge. If you scan in an issue, however you do it, you’re talking hundreds of pages for that month, all of them requiring babysitting to ensure they got through.

- The cheap, cheap paper is a nightmare to run through a scanner – either a flatbed-based misery or a sheet-fed scanner that’s one molecule of damage away from crunching pages up.

- The gutters (space between the spine and the information on the page) is offensively small – millimeters where there should be a half-inch. Especially towards the 1990s era, the instructions to advertisers about layout clearly didn’t make many bones about informing folks about margins. This means the books have to be split apart, a despicable sin that strikes against the heart of the pure.

- These myriad, no-gutter, cheaply-printed pages are both tabloid size and never considered text too small to allow. This means that not only is the page size not going to fit in 95% of the consumer scanners out there, but they’re going to need to be scanned at the highest level you can, to not miss anything. The page size, digitized, is going to be offensively huge.

So, the prospect this would ever happen was basically zero. You needed someone who had the time, inclination, and support to do what was going to be one of the more painful scanning projects extant.

It turned out to be me.

So, there I was whining online about how it was 2023 and nobody seemed to be scanning in Computer Shopper and we were going to be running into greater and greater difficulty to acquire and process them meaningfully, and I finally, stupidly said that if we happened on a somewhat-complete collection, I’d figure out how to do it.

And then an ebay auction came up that seemed to fit the bill.

Out in Ohio, someone decided to sell nearly 200 issues of Computer Shopper for a few thousand bucks.

It’s important to understand the usual per-issue prices for Computer Shopper, and that usual per-issue price can get as high as $50 an issue. Obviously, at some large scale, this becomes an untenably large price. But in this case, they were being sold for about $13 an issue, which is not zero, but somewhere in the realm of manageable: About $3,000 for the lot.

Now, I’m not going to have $3,000 to throw around like that. So I put the challenge out there: If people get together and give me $3,000, I’ll buy this lot and scan it it.

It hit goal in about 3 hours.

As you might have figured out, delivery/mail was not an option. To make that happen, I reached out for a volunteer, and a few people came forward, including Wes Kennedy, who made this his main project for a few days. He’d left one job and was starting another a week later, and “picking up all the issues, packaging them carefully, and putting them in the mail to Jason” became his fun-cation. He deserves all the kudos for this.

When 14 large boxes arrived, they included all the issues, put inside large paper envelopes and wrapped in blue plastic that definitely didn’t look like cocaine to the storage unit guys I cruised past.

So all of the issues were now safely within my control.

One might be inclined to say “Well, that’s only half the problem.” and you’d be off, because it’s actually less than a quarter of the problem. Acquisition, after all, was just money – buying issues in bulk and ending up with a good amount of them was just a case of assembling some cash.

No, it was definitely the scanning that was going to be the big …. issue.

If not obvious, the pages of this tabloid-sized periodical are not just big, they’re over the bounds of pretty much every scanner out there, at least in the consumer space. (There’s plenty of large-format scanners past the $5,000 range, and they’re also gargantuan affairs, meant to handle blueprints and posters.)

But I did find one commercial scanner that could do the work: A Fujitsu fi-7480 wide-size sheet-feed scanner, which tops out at about $3,500. I’ll simply say a kind anonymous donor bought it outright so I wouldn’t have to crowdfund for it, and for that I’m eternally grateful.

Here’s what dealing with that process looks like, with the scanner software (Vuescan) set carefully to neutral and pulling in the massive pages through the fi-7480:

…which brings up the situation involving the pages.

Now, about 12 years ago, I really raked someone over the coals for destroying copies of BYTE magazine to scan them. He was not happy about this at all, and there’s a chance he may have stopped his project just not wanting to deal with such criticism. I hope not, but I do stand by the fact that he indicated he was immediately disposing of the pages after scanning them, which meant any mistakes or oversights were permanent. (At one point, he mentioned having to fish a page out of the trash when he discovered he’d skipped it.)

At that point, I made a declaration of my standards for debinding/pulling apart a magazine to scan it:

“IF I have a document or paper set that requires some level of destruction to scan properly AND IF I have three copies of it AND IF there is no currently-available digital version of the document AND IF there is a call or clamor for this document set THEN AND ONLY THEN I will split the binding and scan at a very high resolution and additionally apply OCR and other modern-day miracles to the resulting document so that the resulting item is, if not greater than the original, more useful to the world.”

…I should have added an OR.

“…OR if there’s very little chance of anyone ever being able to assemble issues to scan in the foreseeable future.”

Because that’s rapidly what was happening with the Computer Shoppers.

$13 an issue is perhaps quite a bit, but people want even more for individual issues and it will be a bit of a stretch to actually acquire them all. So, even though I don’t own 3 copies personally, I also know the other two potential copies are passing among collectors at this point, so they’re being held, in some way, in trust. It’s my hope that I’ll eventually have a chance to do this work for all the issues, but until then, I work with what I got.

Debinding, the taking apart of a bound issue of a magazine to turn it into a stack of papers to scan in, turns out to be a process. A painful, time consuming, involved process. One which I knew would be involved but not as involved as it has definitely turned out to be.

Luckily, people have come before me. There is a rather beautiful documentation out there, about the best practices in debinding magazines, from Retromags. They walk through the pros and cons, the potential issues, the considerations while doing it, and the most common pitfalls that will befell your project if you don’t stay on top of them. I read this like the Book of Life before setting off on dealing with Computer Shoppers, because their “how to ski” primer was going to be critical as I skied backwards down a double-black-diamond slope of these bible-sized monsters.

In this case, I have to use a heat gun, aiming them at the glued issues of Computer Shopper, warming them up until the glue starts to become slightly liquid and then carefully pulling the pages apart from each other, placing them on a large table I’m working on. If the glue comes too close to the pages after I pull them apart, it actually sticks them back again. It’s a huge mess, and with hundreds of pages in a typical issue, hours of work.

There are banger groups out there working tirelessly to debind magazines, scan them in carefully, fix any issues with the looks, and upload them to various locations. One of them is Gaming Alexandria and it’s been a pleasure to fall in with them and discuss the nitty-gritty of this process. They’re scanning in obscure periodicals at scale and they know what they’re up to.

In fact, we’ve made a deal, where I’m just focusing on the “Raw Scans”, and these raws will go to them for post-processing, creating a more readable or functional set of final readable versions of Computer Shopper for people to appreciate. The Raws will always be available, of course – 600dpi TIFF files scanned neutrally of the original pages, placed together in mothra-sized .ZIP files that number up into the many gigabytes, for people to pull down when needed.

A scanned page of a typical issue looks like this (with a little size reduction for this essay):

You can see immediately the difficulties and intricacies of this project.

Like I indicated, there was very little care for margins, and none for minimum size of text. Computer Shopper advertisers did whatever they wanted, however they wanted, and into newsprint, which further made things whacky because bleed is a major issue, pulling the other side’s ink into the current one. And all of this on a massive piece of paper – so in total, the original TIFF file of this image is a full-on 20 megabytes – and this issue has over 400 pages.

And before I forget to mention… I did a test scan with an issue that I had two copies of, to work out any major bugs and problems. And one major problem was that there was a roller at the top of the feed scanner meant to separate a stack of pages into single ones and feed them in properly. Well, that roller grips the page so tightly, it started to pick up ink and put it on later pages, leaving streaks on the page. A quick browse through the service manual, and I had to remove that roller entirely. This means that I have to feed the pages in, one by one, since otherwise it’ll stick them together and jam.

Through all of this, we’re talking hours of work to do a single issue, and I have to do it a couple hundred times at least. This is going to be quite an epic task… which is, again, why we’re down to me doing it because the combination of cost, time and effort leaves almost nobody else who’d be in a position to be able to do, much less want to.

We did one issue, February 1986, “all the way through”. I debinded it, cropped it, scanned it, handed it to Gaming Alexandria to process, got it processed, and then put it on Internet Archive, resulting in three sets of images: The Raw Scans, a “Readable” version and an “Aesthetic” version.

The “Readable” version has been heavily processed and contrasted. It makes it very easy to read a page because it has a really nice dependable color setup for it:

Contrasted with the “Aesthetic” version, that looks more like you would expect the newsprint and bleed-through original to look:

I personally prefer the “Aesthetic” – it brings me back to the way things were when I would buy Computer Shoppers at the local Microcenter and scour them for information and inspiration. But a researcher, and more importantly an Optical Character Recognizer prepping things for searches by researchers, will much prefer working with the Readable version.

Now, Here Comes The Pitch.

So, I live here now.

For the next however-long-it-takes, I’ll be debinding issues, doing careful scans of them, then putting the resulting piles of pages into baggies and sending them into cold storage for permanent holding, awaiting the next time they might have use, or to redo a problematic scan. That’s happening. I’m just going to be on this all year, when I can.

But this effort of mine is rather meaningless unless there are real humans and smart scripts going over what’s being produced.

By a back of the napkin calculation, there will be at least 100,000 and more likely 150,000+ pages of Computer Shopper issues scanned during this project. There’s going to be a lot of them, and they’re going to be jammed full of information, imagery, embarrassment and glory.

I really hope that a group of people, together or separately, start using this bounty to rip out BBS listings, find trends in pricing and nomenclature, in tracking down humble beginnings and finding other amazing tidbits throughout computing history.

It’s nice to drop 400-800 pages at once into an item, but unless I get some of those nerds out there scouring the pages for interesting things, it’s just me scanning into a void.

If you know people will be interested, help them become aware. And if you see something interesting, bring it out and make it part of sharing, wherever you want to.

This will be an incredible amount of work. Folks threw thousands of dollars into acquisitions of hardware and paper and I’m going to blast a lot of my personal time into scanning these.

Make it worth it.

Addendum:

This entry got a lot of attention. Two questions arose, and I’ll answer them both here:

Are There Missing Issues?

Yes, there are. Here’s the list. If people want to donate or buy good quality copies for me, mail me at jason@textfiles.com. Here’s the missing issues as far as I can tell:

- Everything before November 1983

- 1984: January, October, November

- 1985: October

- 1988: June, November

- 1989: April

- 1994: April, May, August, November

- 1995: February, March

- 1996: April, May, June

- 1997: July, September

- 1998: January, May

- 1999: April, July, August

If people send them to me, I’ll take them off this list. So if this list is here, I’m still missing them.

Can I Help Support You?

Just enjoy the Podcast. I spend a lot of time on it.

]]>What I’m talking about is something else entirely.

It’s a situation where people want all the cachet of being outside the boundaries, in lawless territories where you survive on the wit and bravery (or brutality) of Taking The Initiative and damn the costs and risks, but also want to be protected and safe with all the constructs we in Civilization provide so you don’t wake up with your throat slit and your pockets turned out.

They want a fictional in-between place that doesn’t bend to the “inconvenient” rules and yet lets you summon them in a moment’s (or hour’s) notice when the game doesn’t go your way and you need to get the DM to re-roll for a Natural 20.

I have my own term for this phenomenon: The Aboveground, a mystical (and profitable) land where people want to believe they’re under the radar, being all subtle and hidden, when they’re actually functioning in plain sight.

(This is very different, I should note, from people who are functioning in an underground manner in plain sight with knowing intention of being watched and findable, just doing so in a double-switchback situation that means they function in that environment. Most people don’t actually want to take on the burden of this, but some do.)

I’ll give a hypothetical that I’ve used before trying to explain my thinking.

The Underground wants to do sketchy shit, so by word of mouth, everyone knows to meet over at Ken’s house, and Ken has a separate basement door entrance, so you know to park down the street and go to Ken’s house and let yourself in the gate and knock on Ken’s basement door and Ken lets you in because other people said you were cool. Once you’re all in there, drinking beers, everyone gathers up the stuff you’re going to do sketchy shit with and you head out into the woods and do sketchy shit.

The Aboveground wants to do all the woods stuff, except you meet at Starbucks and post it on multiple forums and tweet about it using some stupid codeword and also you want a sign at Starbucks telling people the Sketchy Shit Club meets around 6pm every Friday.

The simple fact is, we’ve been spending so many Herculean efforts to bring every single aspect of life online and make communication by massive observed networks and corporate-owned byways and highways that many people don’t even see these worlds as anything other than “the world”. From that lack of perception comes the continued desire to stay out of the eye of the public, or at least out of the eye of authority, to do neat or weird stuff that others might not approve of.

And yet, the fact is (or should be) that doing risky things entails risks. Playfully pop out of the window of your pal’s car to get on the roof to goof around, and you might injure yourself and die. Modify electronics or equipment to do something neat, and you might cross a wire and bust it up permanently, or (again) injure yourself. Take stupid chances, win stupid prizes, right?

But the growing denizens of the Aboveground don’t entirely like that. They’ve either internalized or integrated into their worldview that somewhere, out beyond the bounds of sight, they will always have a safety net, a ramp or an apparatus, that will ultimately provide comfort and rescue to pull them back from the abyss.

And to be clear: It’s an awesome deal if you can get it.

I, myself, have absolutely benefitted from taking wild swings at the fences and going out into the darkness with a flashlight and a prayer, emerging messy, sweaty, with a few cuts and a recurring nightmare about what almost happened there that one time. In my mind, the idea that ultimately, whoever or whatever found us would first try and get the injuries handled at a hospital, or would probably toss us at the edge of the border with an admonishment to not come back, was always humming along in the background, warm and safe. I’ve certainly walked in the Aboveground and fooled myself with the illusion that I wasn’t.

But that’s the point: The Aboveground is the Aboveground but it’s also the Illusion of the Underground cooked into it.

Perhaps that’s where I started to sour on it all, and recognize it for what it was: Cosplay for Hardship; a Kabuki Theater of acting out the long-worn tropes of the outlaw you once were, wearing the new business suit of what you actually are.

The Aboveground is a template that fits in hundreds of situations.

The reason I bring up this thought experiment and sidebar is related to the two most frequent times I see it in use, personally.

First, it’s what I started to see over the years as I would attend a lot of “hacking” conventions, where it was clear that the realms of curiosity and risk were being traded for 401(k)s, contract-driven shrunk horizons, and the safety and dependability for family. No shame in that. But yet, as that morphing and breaking out of the rebellious chrysalis happened, there was an insistence, or, more a demand that the strange, confused, brilliant and deranged hacking mentality be worn as a faded t-shirt or jacket throughout the process.

Hacking conferences are, in the present sense, overly Aboveground – they have to be. There are contracts signed, real names writing real checks with conference centers and multinationals that price out damage and vandalism, along with an at-call internal and external security force primarily focused on Stopping Crimes…. and yet people either still do the crimes, or they pretend that in some way, some squint-and-you-can-see-it version of being an outsider still persists with your name on the room and a credit card for the flight that brought you here. It’s endemic, marbled into the aging steak of these events, and it’s why, with very very little exception, I only attend ones I both like and which I can drive home from the same day.

And then there’s the other situation.

The entire technical industry and infrastructure space, especially the really “disruptive” ones, has progressively built itself not only on the idea that you should ignore the rules until someone actively stops you or you can get bought out, it nearly depends on it.

Fat with venture capital, bloated with many levels of management and oversight, and exhibiting absolutely no understanding of what represents long-long-term integration into the operations of humanity, good and bad, they instead chose the Aboveground lifestyle.