| CARVIEW |

Instead, we should have helpful error messages explaining why a property does not hold; which parts of the specification failed and which concrete values from the trace were involved. Not false, unsat, or even assertion error: x != y. We should get the full story. I started exploring this space a few years ago when I worked actively on Quickstrom, but for some reason it went on the shelf half-finished. Time to tie up the loose ends!

The starting point was Picostrom, a minimal Haskell version of the checker in Quickstrom, and Error Reporting Logic (ERL), a paper introducing a way of rendering natural-language messages to explain propositional logic counterexamples. I ported it to Rust mostly to see what it turned into, and extended it with error reporting supporting temporal operators. The code is available at codeberg.org/owi/picostrom-rs under the MIT license.

Between the start of my work and picking it back up now, A Language for Explaining Counterexamples was published, which looks closely related, although it’s focused on model checking with CTL. If you’re interested in other related work, check out A Systematic Literature Review on Counterexample Explanation in Model Checking.

All right, let’s dive in!

QuickLTL and Picostrom

A quick recap on QuickLTL is in order before we go into the Picostrom code. QuickLTL operates on finite traces, making it suitable for testing. It’s a four-valued logic, meaning that a formula evaluates to one of these values:

- definitely true

- definitely false

- probably true

- probably false

It extends propositional logic with temporal operators, much like LTL:

- nextd(P)

-

P must hold in the next state, demanding a next state is available. This forces the evaluator to draw a next state.

- nextf(P)

-

P must hold in the next state, defaulting to definitely false if no next state is available.

- nextt(P)

-

P must hold in the next state, defaulting to probably true if no next state is available.

- eventuallyN(P)

-

P must hold in the current or a future state. It demands at least N states, evaluating on all available states, finally defaulting to probably false.

- alwaysN(P)

-

P must hold in the current and all future states. It demands at least N states, evaluating on all available states, finally defaulting to probably true.

You can think of eventuallyN(P) as unfolding into a sequence of N nested nextd, wrapping an infinite sequence of nextf, all connected by ∨. Let’s define that inductively with a coinductive base case:

$$ \begin{align} \text{eventually}_0(P) & = P \lor \text{next}_F(\text{eventually}_0(P)) \\ \text{eventually}_(N + 1)(P) & = P \lor \text{next}_D(\text{eventually}_N(P)) \\ \end{align} $$

And similarly, alwaysN(P) can be defined as:

$$ \begin{align} \text{always}_0(P) & = P \land \text{next}_T(\text{always}_0(P)) \\ \text{always}_(N + 1)(P) & = P \land \text{next}_D(\text{always}_N(P)) \\ \end{align} $$

This is essentially how the evaluator expands these temporal operators, but for error reporting reasons, not exactly.

Finally, there are atoms, which are domain-specific expressions embedded in the AST, evaluating to ⊤ or ⊥. The AST is parameterized on the atom type, so you can plug in an atom language of choice. An atom type must implement the Atom trait, which in simplified form looks like this:

trait Atom { type State; fn eval(&self, state: &Self::State) -> bool; fn render( &self, mode: TextMode, negated: bool, ) -> String; fn render_actual( &self, negated: bool, state: &Self::State, ) -> String; }For testing the checker, and for this blog post, I’m using the following atom type:

enum TestAtom { Literal(u64), Select(Identifier), Equals(Box<TestAtom>, Box<TestAtom>), LessThan(Box<TestAtom>, Box<TestAtom>), GreaterThan(Box<TestAtom>, Box<TestAtom>), } enum Identifier { A, B, C, }Evaluation

The first step, like in ERL, is transforming the formula into negation normal form (NNF), which means pushing down all negations into the atoms:

This makes it much easier to construct readable sentences, in addition to another important upside which I’ll get to in a second. The NNF representation is the one used by the evaluator internally.

Next, the eval function takes an Atom::State and a Formula, and produces a Value:

A value is either immediately true or false, meaning that we don’t need to evaluate on additional states, or a residual, which describes how to continue evaluating a formula when given a next state. Also note how the False variant holds a Problem, which is what we’d report as definitely false. The True variant doesn’t need to hold any such information, because due to NNF, it can’t be negated and “turned into a problem.”

I won’t cover every variant of the Residual type, but let’s take one example:

enum Residual<'a, A: Atom> { // ... AndAlways { start: Numbered<&'a A::State>, left: Box<Residual<'a, A>>, right: Box<Residual<'a, A>>, }, // ... }When such a value is returned, the evaluator checks if it’s possible to stop at this point, i.e. if there are no demanding operators in the residual. If not possible, it draws a new state and calls step on the residual. The step function is analogous to eval, also returning a Value, but it operates on a Residual rather than a Formula.

The AndAlways variant describes an ongoing evaluation of the always operator, where the left and right residuals are the operands of ∧ in the inductive definition I described earlier. The start field holds the starting state, which is used when rendering error messages. Similarly, the Residual enum has variants for ∨, ∧, ⟹, next, eventually, and a few others.

When the stop function deems it possible to stop evaluating, we get back a value of this type:

Those variants correspond to probably true and probably false. In the false case, we get a Problem which we can render. Recall how the Value type returned by eval and step also had True and False variants? Those are the definite cases.

Rendering Problems

The Problem type is a tree structure, mirroring the structure of the evaluated formula, but only containing the parts of it that contributed to its falsity.

enum Problem<'a, A: Atom> { And { left: Box<Problem<'a, A>>, right: Box<Problem<'a, A>>, }, Or { left: Box<Problem<'a, A>>, right: Box<Problem<'a, A>>, }, Always { state: Numbered<&'a A::State>, problem: Box<Problem<'a, A>>, }, Eventually { state: Numbered<&'a A::State>, formula: Box<Formula<A>>, }, // A bunch of others... }I’ve written a simple renderer that walks the Problem tree, constructing English error messages. When hitting the atoms, it uses the render and render_actual methods from the Atom trait I showed you before.

The mode is very much like in the ERL paper, i.e. whether it should be rendered in deontic (e.g. “x should equal 4”) or indicative (e.g. “x equals 4”) form:

The render method should render the atom according to the mode, and render_actual should render relevant parts of the atom in a given state, like its variable assignments.

With all these pieces in place, we can finally render some error messages! Let’s say we have this formula:

eventually10(B = 3 ∧ C = 4)

If we run a test and never see such a state, the rendered error would be:

Probably false: eventually B must equal 3 and C must equal 4, but it was not observed starting at state 0

Neat! This is the kind of error reporting I want for my stateful tests.

Implication

You can trace why some subformula is relevant by using implication. A common pattern in state machine specs and other safety properties is:

precondition ⟹ before ∧ nextt(after)

So, let’s say we have this formula:

alwaysN((A > 0) ⟹ (B > 5 ∧ nextt(C < 10)))

If B or C are false, the error includes the antecedent:

Definitely false: B must be greater than 5 and in the next state, C must be less than 10 since A is greater than 0, […]

Small Errors, Short Tests

Let’s consider a conjunction of two invariants. We could of course combine the two atomic propositions with conjunction inside a single always(...), but in this case we have the formula:

always(A < 3) ∧ always(B < C)

An error message, where both invariants fail, might look the following:

Definitely false: it must always be the case that A is less than 3 and it must always be the case that B is greater than C, but A=3 in state 3 and B=0 in state 3

If only the second invariant (B < C) fails, we get a smaller error:

Definitely false: it must always be the case that B is greater than C, but B=0 and C=0 in state 0

And, crucially, if one of the invariants fail before the other we also get a smaller error, ignoring the other invariant. While single-state conjunctions evaluate both sides, possibly creating composite errors, conjunctions over time short-circuit in order to stop tests as soon as possible.

Diagrams

Let’s say we have a failing safety property like the following:

nextd(always8(B < C))

The textual error might be:

Definitely false: in the next state, it must always be the case that B is greater than C, but B=13 and C=15 in state 6

But with some tweaks we could also draw a diagram, using the Problem tree and the collected states:

Or for a liveness property like nextd(eventually8(B = C)), where there is no counterexample at a particular state, we could draw a diagram showing how we give up after some time:

These are only sketches, but I think they show how the Problem data structure can be used in many interesting ways. What other visualizations would be possible? An interactive state space explorer could show how problems evolve as you navigate across time. You could generate spreadsheets or HTML documents, or maybe even annotate the relevant source code of some system-under-test? I think it depends a lot on the domain this is applied to.

No Loose Ends

It’s been great to finally finish this work! I’ve had a lot of fun working through the various head-scratchers in the evaluator, getting strange combinations of temporal operators to render readable error messages. I also enjoyed drawing the diagrams, and almost nerd-sniped myself into automating that. Maybe another day. I hope this is interesting or even useful to someone out there. LTL is really cool and should be used more!

The code, including many rendering tests cases, is available at codeberg.org/owi/picostrom-rs.

A special thanks goes to Divyanshu Ranjan for reviewing a draft of this post.

]]>This is not a sponsored post.

Why do I even bother, you might ask? Sunlight makes me energetic and alert, which I need when I work. Living in the Nordics, 50% of the year is primarily dark, so any direct daylight I can get becomes really important. I usually run light mode on my Framework laptop during the day, but working in actual daylight with these displays, or plain old paper, is even better.

The Setup

Here are the main components of this coding environment:

- Daylight DC-1: an Android-based tablet with a “Live Paper” display (Reflective LCD, not E-Ink)

- 8BitDo Retro Mechanical Keyboard: a mechanical Bluetooth-enabled keyboard, with Kailh key switches and USB-C charging and optional connection

- Termux: a terminal emulator for Android, with a package collection based on

apt - SSH, tmux, and Neovim: nothing surprising here

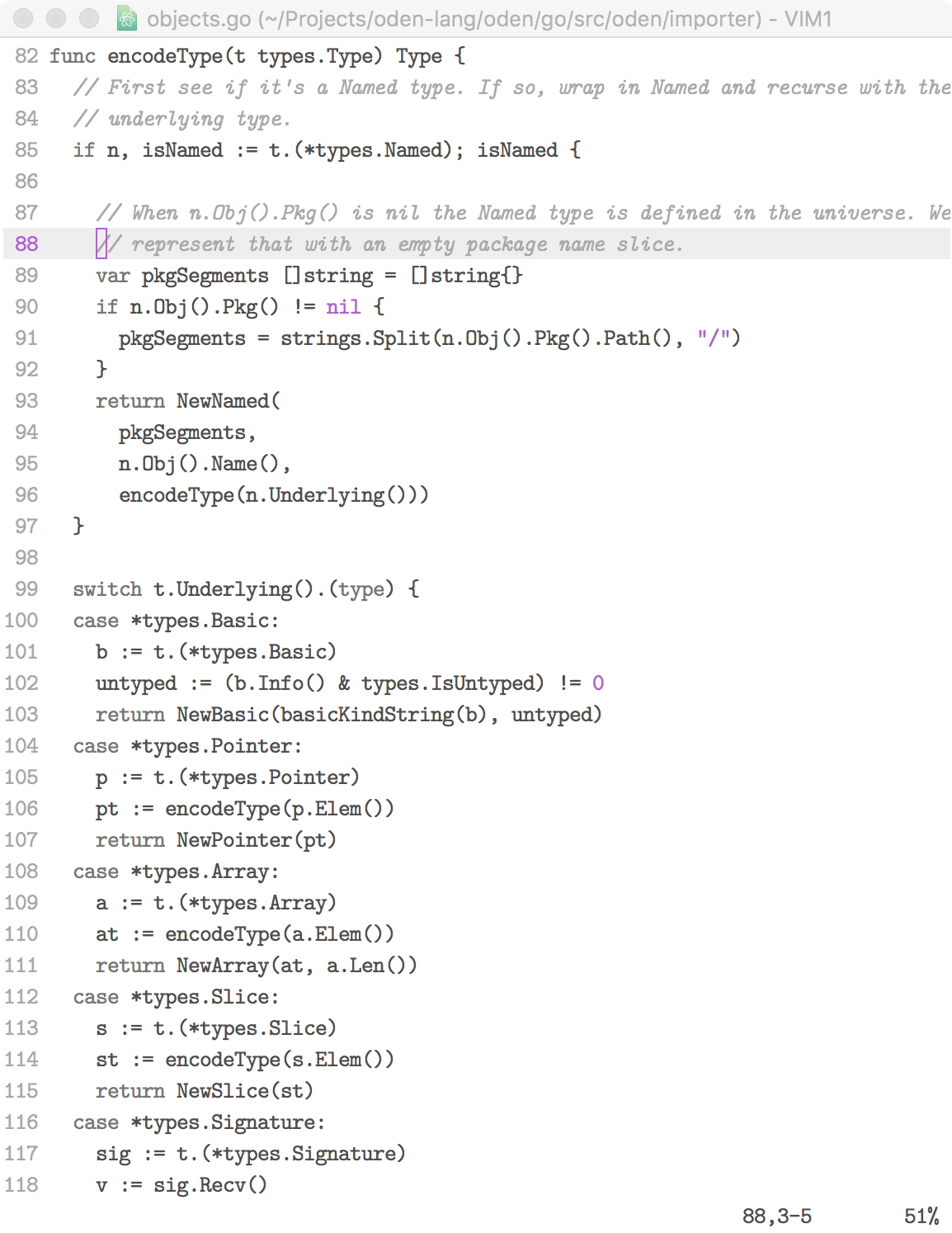

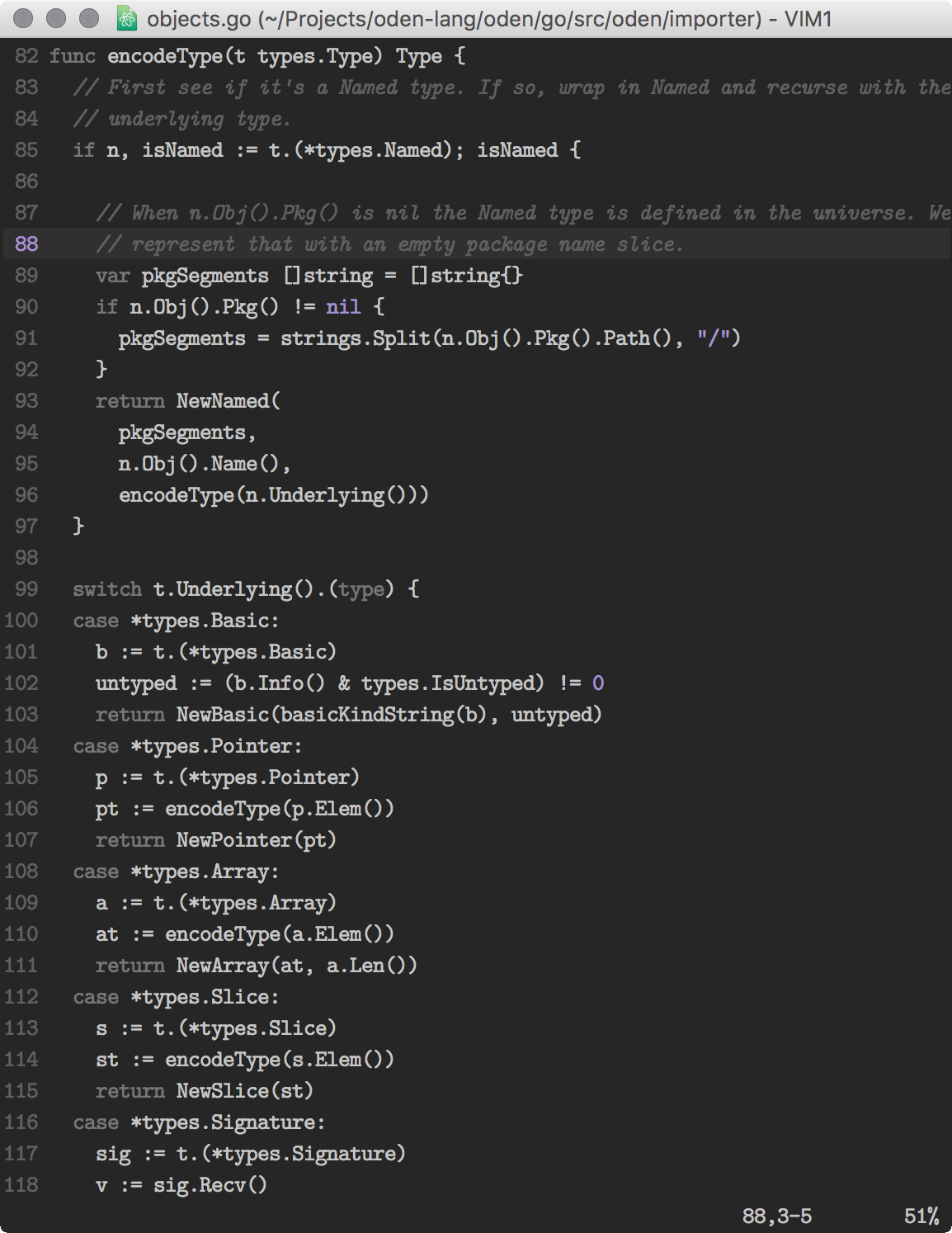

I use a slimmed-down version of my regular dotfiles, because this setup doesn’t use Nix. I’ve manually installed Neovim, tmux, and a few other essentials, using the package manager that comes with Termux. I’ve configured Termux to not show its virtual keyboard when a physical keyboard is connected (the Bluetooth keyboard). The Termux theme is “E-Ink” and the font is JetBrains Mono, all built into Termux. Neovim uses the built-in quiet colorscheme for maximum contrast.

Certain work requires a more capable environment, and in those cases I connect to my workstation using SSH and run tmux in there. For writing or simpler programming projects (I’ve even done Rust work with Cargo, for instance), the local Termux environment is fine.

Sometimes I want to go really minimalist, so I hide the tmux status bar and run Goyo in Neovim. Deep breaths. Feel the fresh air in your lungs. This is especially nice for writing blog posts like this one.

My blog editing works locally in Termux, with a live reloading Chrome in a split window, here during an evening writing session with the warm backlight enabled:

There’s the occasional Bluetooth connection problem with the 8BitDo keyboard. I also don’t love the layout, and I’m considering getting the Kinesis Freestyle2 Blue instead. I already have the wired version for my workstation, and the ergonomics are great.

Daylight DC-1 vs Boox Tab Ultra

What about the Boox? I’ve had this device for longer and I really like it too, but not for the same tasks. The E-Ink display is, quite frankly, a lot nicer to read on; EPUB books, research PDFs, web articles, etc. The 227 PPI instead of the Daylight’s 190 PPI makes a difference, and I like the look of E-Ink better overall.

However, the refresh rate and ghosting make it a bit frustrating for typing. Same goes for drawing, which I’ve used the Daylight for a lot. Most of my home renovation blueprints are sketched on the Daylight. The refresh rate makes it possible.

When reading at night with a more direct bedside lamp, often in combination with a subtle backlight, the Boox is much better. The Daylight screen can glare quite a bit, so the only option is backlight only. And at that point, a lot of the paperlike quality goes away.

You can also get some glare when there’s direct sunlight at a particular angle:

Even if I don’t write or program directly on the Boox, I’ve experimented with using it as a secondary display, like for the live reload blog preview:

To sum up, these devices are good for different things, in my experience. I’ve probably spent more time on the Boox, because I’ve had it for longer and I’ve read a lot on it, but the Daylight has been much better for typing and drawing.

Another thing I’d like to try is a larger E-Ink monitor for my workstation, like the one Zack is hacking on. I’m hoping this technology continues to improve on refresh rate, because I love E-Ink. Until then, the Daylight is a good compromise.

The goal is to get one of Amp’s most central pieces, the ThreadWorker, under heavy scrutiny. We’ve had a few perplexing bug reports, where users experienced corrupted threads, LLM API errors from invalid tool calls, and more vague issues like “it seems like it’s spinning forever.” Reproducing such problems manually is usually somewhere between impractical and impossible. I want to reproduce them deterministically, and in a way where we can debug and fix them. And beyond the known ones, I’d like to find the currently unknown ones before our users hit them.

Generative testing to the rescue!

Approach: Lightweight DST in TypeScript

Amp is written in TypeScript, which is an ecosystem currently not drowning in fuzzing tools. My starting point was using jsfuzz, which I hadn’t used before but it looked promising. However, I had a bunch of problems getting it to run together with our Bun stack. One could use fast-check, but as far as I can tell, the model-based testing they support doesn’t fit with our needs. We don’t have a model of the system, and we need to generate values in multiple places as the test runs. So, I decided to build something from scratch for our purposes.

I borrowed an idea I got from matklad last year: instead of passing a seeded PRNG to generate test input, we generate an entropy Buffer with random contents, and track our position in that array with a cursor. Drawing a random byte consumes the byte at the current position and increments the cursor. We don’t know up-front how many bytes we need for a given fuzzer, so the entropy buffer grows dynamically when needed, appending more random bytes. This, together with a bunch of methods for drawing different types of values, is packaged up in an Entropy class:

class Entropy { random(count): UInt8Array { ... } randomRange(minIncl: number, maxExcl: number): number { ... } // ... lots of other stuff }A fuzzer is an ES module written in TypeScript, exporting a single function:

Any exception thrown by fuzz is considered a test failure. We use the node:assert module for our test assertions, but it could be anything.

Another program, the fuzz runner, imports a built fuzzer module and runs as many tests it can before a given timeout. If it finds a failure, it prints out the command to reproduce that failure:

Fuzzing example.fuzzer.js iteration 1000... Fuzzing example.fuzzer.js iteration 2000... Fuzzer failed: AssertionError [ERR_ASSERTION]: 3 != 4 at [...] Reproduce with: bun --console-depth=10 scripts/fuzz.ts \ dist/example.fuzzer.js \ --verbose \ --reproduce=1493a513f88d0fd9325534c33f774831Why use this Entropy rather than a seed? More about that at the end of the post!

The ThreadWorker Fuzzer

In the fuzzer for our ThreadWorker, we stub out all IO and other nondeterministic components, and we install fake timers to control when and how asynchronous code is run. In effect, we have determinism and simulation to run tests in, so I guess it qualifies as DST.

The test simulates a sequence of user actions (send message, cancel, resume, and wait). Similarly, it simulates responses from tool calls (like the agent reading a file) and from inference backends (like the Anthropic API). We inject faults and delays in both tool calls and inference requests to test our error handling and possible race conditions.

After all user actions have been executed, we make sure to approve any pending tool calls that require confirmation. Next, we tell the fake timer to run all outstanding timers until the queue is empty; like fast-forwarding until there’s nothing left to do. Finally, we check that the thread is idle, i.e. that there’s no ongoing inference and that all tool calls have terminated. This is a liveness property.

After the liveness property, we check a bunch of safety properties:

- all messages posted by the user are present in the thread

- all message pairs involving tools calls are valid according to Anthropic’s API specification

- all tool calls have settled in expected terminal states

Some of these are targeted at specific known bugs, while some are more general but have found bugs we did not expect.

Here’s a highly simplified version of the fuzzer:

export async function fuzz(entropy: Entropy) { const clock = sinon.useFakeTimers({ loopLimit: 1_000_000, }) const worker = setup() // including stubbing IO, etc try { const resumed = worker.resume() await clock.runAllAsync() await resumed async function run() { for (let round = 0; round < entropy.randomRange(1, 50); round++) { const action = await generateNextAction(entropy, worker) switch (action.type) { case 'user-message': await worker.handle({ ...action, type: 'user:message', }) break case 'cancel': await worker.cancel() break case 'resume': await worker.resume() break case 'sleep': await sleep(action.milliseconds) break case 'approve': { await approveTool(action.threadID, action.toolUseID) break } } } // Approve any remaining tool uses to ensure termination into an // idle thread state const blockedTools = await blockedToolUses() await Promise.all(blockedTools.map(approve)) } const done = run() await clock.runAllAsync() await done // check liveness and safety properties // ... } finally { sinon.restore() } }Now, let’s dig into the findings!

Results

Given I’ve been working on this for about a week in total, I’m very happy with the outcome. Here are some issues the fuzzer found:

- Corrupted thread due to eagerly starting tool calls during streaming

-

While streaming tool use blocks from the Anthropic API, we invoked tools eagerly, while not all of them were finished streaming. This, in combination with how state was managed, led to tool results being incorrectly split across messages. Anthropic’s API would reject any further requests, and the thread would essentially be corrupted. This was reported by a user and was the first issue we found and fixed using the fuzzer.

Another variation, which the fuzzer also found, this was a race condition where user messages interfered at a particular timing with ongoing tool calls, splitting them up incorrectly.

- Subagent tool calls not terminating when subthread tool calls were rejected

-

Due to a recent change in behavior, where we don’t run inference automatically after tool call rejection, subagents could end up never signalling their termination, which led to the main thread never reaching an idle state.

I confirmed this in both VSCode and the CLI: infinite spinners, indeed.

- Tool calls blocked on user not getting cancelled after user message

-

Due to how some tool calls require confirmation, like reading files outside the workspace or running some shell commands, in combination how we represent and track termination of tools, there’s a possibility for such tools to be resumed and then, after an immediate user cancellation, not be properly cancelled. This leads to incorrect mutations of the thread data.

I’ve not yet found the cause of this issue, but it’s perfectly reproducible, so that’s a start.

Furthermore, we were able to verify an older bug fix, where Anthropic’s API would send an invalid message with an empty tool use block array. That used to get the agent into an infinite loop. With the fuzzer, we verified and improved the old fix which had missed another case.

How about number of test runs and timeouts? Most of these bugs were found almost immediately, i.e. within a second. The last one in the list above takes longer, around a minute normally. We run a short version of each fuzzer in every CI build, and longer runs on a nightly basis. This is up for a lot of tuning and experimentation.

Why the Entropy Buffer?

So why the entropy buffer instead of a seeded PRNG? The idea is to use that buffer to mutate the test input, instead of just bombarding with random data every time. If we can track which parts of the entropy was used where, we can make those slices “smaller” or “bigger.” We can use something like gradient descent or simulated annealing to optimize inputs, maximizing some objective function set by the fuzzer. Finally, we might be able to minimize inputs by manipulating the entropy.

In case the JavaScript community gets some powerful fuzzing framework like AFL+, that could also just be plugged in. Who knows, but I find this an interesting approach that’s worth exploring. I believe the entropy buffer approach is also similar to how Hypothesis works under the hood. Someone please correct me if that’s not the case.

Anyhow, that’s today’s report from the generative testing mines. Cheers!

]]>I know there are probably tons of blog posts by the newly converted. I’m not trying to offer any grand insights, I’m just documenting my process and current ideas.

Gradually, Then Suddenly

I’ve been a typical sceptic of Copilot and similar tools. Sure, it’s nice to generate boilerplate and throw-away scripts, but that’s a minor part of what we do all day, right? I even took a break from using them for many months, and I’ve had serious qualms with their use in some areas outside coding.

After messing around with copilot.lua in Neovim, I tried Cursor. Their vision and what they’ve already built opened my eyes, especially the shadow workspaces, Tab, and the rule files. At the same time, a critical mass of friends and peers were building new products on top of these models; things I highly respect and can see massive value in.

Since then I’ve actively been looking for how I can use LLMs — beyond the auto-complete and chat interaction modes, beyond making me a slightly more productive developer. Don’t get me wrong, I love being alone coding for hours in a cozy room. It’s great. But I’m also curious to see how far I can push this myself, and of course how far and where the industry goes.

Taking on New Projects

One project that I’ve been working on goes under the working name site2doc. It’s a tool that converts entire web sites into EPUB and PDF books. Mostly because I want it for myself. I’d like to read online material, typeset minimalistically and beautifully, offline on my ebook reader. It turned out others want that too. There are great tools for converting single pages, but not for entire sites.

My main problem is that the web is highly unstructured and diverse. To be frank, a lot of sites have really bad markup. No titles at all, identical titles across pages, <h1> elements used inconsistently. The list goes on. This makes it very difficult for site2doc to generate a useful table of contents.

A friend suggested using LLMs to extract the information, and I experimented with using screenshots as input to classify pages. Both Claude 3.5 Sonnet and Gemini 2.0 Flash performed well, but I haven’t been able to generalize the approach across many sites. There’s just too much variability in how websites are structured, and I’m not sure how to handle it. I’m open to suggestions!

The other project, temporarily named converge, is a bit closer to what everyone else is doing: using LLMs for programming. It’s an agent that, given some file or module, covers it with a generated test suite, and then goes on to optimize it. The key idea is that the original code is the source of truth. The particular optimization goal could be performance, resource usage, readability, safety, or robustness. So far I’ve focused only on performance, partly because evaluation is straightforward.

Going beyond example-based test suites, I’ve been thinking about how property-based testing (PBT) might fit in. The obvious approach is to have the LLM generate property tests rather than examples. I don’t know how well this would work, if the LLM can generate meaningful properties.

A more interesting way is to generate an oracle property that compares the behavior of new code generated by the LLM to the original code: ∀i.old(i) = new(i), where i is some generated input. This provides a rigorous way to verify that optimizations preserve the original behavior. I’m curious to see how PBT’s shrinking could guide the LLM to iteratively fix the generated code.

Another random idea: have the LLM explain existing code in natural language, then generate new code based only on the description. Run the old and new code side-by-side, and see how they differ, functionally and non-functionally.

I’ve only run converge on toy examples and snippets so far. I’m sure there are major challenges in applying it to larger code bases. Here’s what it currently does to Achilles numbers in Rosetta Code:

» converge -input AchillesNumbers.java time=2025-02-11T09:35:44.877+01:00 level=INFO msg="test suite created" time=2025-02-11T09:35:45.271+01:00 level=WARN msg="tests failed" attempt=1 time=2025-02-11T09:35:53.308+01:00 level=INFO msg="test suite modified" time=2025-02-11T09:35:53.709+01:00 level=WARN msg="tests failed" attempt=2 time=2025-02-11T09:36:02.457+01:00 level=INFO msg="test suite modified" time=2025-02-11T09:36:02.885+01:00 level=INFO msg="tests passed" time=2025-02-11T09:36:09.508+01:00 level=INFO msg="increasing benchmark iterations" duration=0.038339998573064804 attempt=0 time=2025-02-11T09:36:15.056+01:00 level=INFO msg="increasing benchmark iterations" duration=0.2295980006456375 attempt=1 time=2025-02-11T09:36:21.225+01:00 level=INFO msg="increasing benchmark iterations" duration=0.5998150110244751 attempt=2 time=2025-02-11T09:36:28.010+01:00 level=INFO msg="benchmark run" time=2025-02-11T09:36:35.737+01:00 level=INFO msg="code optimized" attempt=0 time=2025-02-11T09:38:19.094+01:00 level=INFO msg="tests failed" ... time=2025-02-11T09:38:33.798+01:00 level=INFO msg="code optimized" attempt=9 optimization succeeded: 1.870953s -> 1.337585s (-28.51%)That took about three minutes. It does all sorts of tricks to make it faster, but one that caught my eye was the conversion from HashMap<Integer, Boolean> to HashSet<Integer>, and finally to BitSet. Here’s part of the diff:

... public class AchillesNumbers { - - private Map<Integer, Boolean> pps = new HashMap<>(); + private final BitSet pps = new BitSet(); + private final BitSet achillesCache = new BitSet(); + private static final byte[] SMALL_PRIMES = {2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47}; + private static final int[] POWERS_OF_TEN = {1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 1000000, 10000000, 100000000}; + private static final short[] SQUARES = new short[317]; + private static final int[] CUBES = new int[47]; + private static final short[] TOTIENTS = new short[1000]; ... }Unlearning

I’m surprised to find myself as excited as I am now. I did not see it coming! Just during the last few days, I’ve realized how much I need to unlearn in order to make better use of what these models have learned.

I was implementing control flow, using Claude to generate various bits of code for the converge tool. Then I realized that, hey, maybe it should be the other way around? Claude plans the control flow, and my tool just provides the ways of interacting with the environment (modifying source files, running tests, etc). It’s not a revelation, but an example of how one might need to think differently.

Even more down to earth, things like saying “do X for me” rather than asking “how do I do X?”. Instead of asking for some chunk of code, I tell it to solve a problem for me. Of course, I still review the changes. Cursor and Cody have both been great ways of changing my thinking.

What other habits and thought patterns might need to change? I don’t know how programming will look in the future, but I’m actively working on keeping an open mind and hopefully playing a small role in shaping it.

Comment on Hacker News or X.

]]>This morphed into a technical challenge, while still having that creative aspect that I started with. Subsequent screenshots with the fixed grid and responsive tables sparked a lot of interest. About a week later I published the source, and since then there’s been a lot of forks. People use it for their personal web sites, mostly, but also for apps.

I’d like to explain how it works. Not everything, just focusing on the most interesting parts.

The Fixed Grid

This design aligns everything, horizontally and vertically, to a fixed grid. Like a table with equal-size cells. Every text character should be exactly contained in a cell in that grid. Borders and other visual elements may span cells more freely.

The big idea here is to use the ch unit in CSS. I actually did not know about it before this experiment. The ch unit is described in CSS Values and Units Module Level 4:

Represents the typical advance measure of European alphanumeric characters, and measured as the used advance measure of the “0” (ZERO, U+0030) glyph in the font used to render it.

Further, it notes:

This measurement is an approximation (and in monospace fonts, an exact measure) of a single narrow glyph’s advance measure, thus allowing measurements based on an expected glyph count.

Fantastic! A cell is thus 1ch wide. And the cell height is equal to the line-height. In order to refer to the line height in calculations, it’s extracted as a CSS variable:

So far there’s no actual grid on the page. This is just a way of measuring and sizing elements based on the width and height of monospace characters. Every element must take up space evenly divisible by the dimensions of a cell; if it’s top left corner starts at a cell, then its bottom right must do so as well. That means that all elements, given that their individual sizes respect the grid, line up properly.

The Font

I’ve chosen JetBrains Mono for the font. It looks great, sure, but there’s a more important reason for this particular choice: it has good support for box-drawing characters at greater line heights. Most monospace fonts I tried broke at line heights above 110% or so. Lines and blocks were chopped up vertically. With JetBrains Mono, I can set it to 120% before it starts to become choppy.

I suspect Pragmata Pro or Berkeley Mono might work in this regard, but I haven’t tried them yet.

Also, if you want to use this design and with a greater line height, you can probably do so if you don’t need box-drawing characters. Then you may also consider pretty much any monospace font. Why not use web-safe ones, trimming down the page weight by about 600kB!

To avoid alternate glyphs for numbers, keeping everything aligned to the grid, I set:

And, for a unified thickness of borders, text, and underlines:

:root { --border-thickness: 2px; font-weight: 500; text-decoration-thickness: var(--border-thickness); }This gives the design that thick and sturdy feel.

The Body

The body element is the main container in the page. It is at most 80 characters wide. (Huh, I wonder where that number came from?)

Now for one of the key tricks! I wanted this design to be reasonably responsive. For a viewport width smaller than 84ch (80ch and 4ch of padding), the body width needs to be some smaller width that is still evenly divisible by the cell dimensions. This can be accomplished with CSS rounding:

This way, the body shrinks in steps according to the grid.

The Horizontal Rule

Surprisingly, the custom horizontal rule styling was a fiddly enterprise. I wanted it to feel heavy, with double lines. The lines are vertically centered around the break between two cells:

To respect the grid, the top and bottom spacing needs to be calculated. But padding won’t work, and margin interacts with adjacent elements’ margins, so this required two elements:

hr { position: relative; display: block; height: var(--line-height); margin: calc(var(--line-height) * 1.5) 0; border: none; color: var(--text-color); } hr:after { display: block; content: ""; position: absolute; top: calc(var(--line-height) / 2 - var(--border-thickness)); left: 0; width: 100%; border-top: calc(var(--border-thickness) * 3) double var(--text-color); height: 0; }The hr itself is just a container that takes up space; 4 lines in total. The hr:after pseudo-element draws the two lines, using border-top-style, at the vertical center of the hr.

The Table

Table styling was probably the trickiest. Recalling the principles from the beginning, every character must be perfectly aligned with the grid. But I wanted vertical padding of table cells to be half the line height. A full line height worth of padding is way too airy.

This requires the table being horizontally offset by half the width of a character, and vertically offset by half the line height.

table { position: relative; top: calc(var(--line-height) / 2); width: calc(round(down, 100%, 1ch)); border-collapse: collapse; }Cell padding is calculated based on cell size and borders, to keep grid alignment:

th, td { border: var(--border-thickness) solid var(--text-color); padding: calc((var(--line-height) / 2)) calc(1ch - var(--border-thickness) / 2) calc((var(--line-height) / 2) - (var(--border-thickness))) ; line-height: var(--line-height); }Finally, the first row must have slightly less vertical padding to compensate for the top border. This is hacky, and would be nicer to solve with some kind of negative margin on the table. But then I’d be back in margin interaction land, and I don’t like it there.

table tbody tr:first-child > * { padding-top: calc( (var(--line-height) / 2) - var(--border-thickness) ); }Another quirk is that columns need to have set sizes. All but one should use the width-min class, and the remaining should use width-auto. Otherwise, cells divide the available width in a way that doesn’t align with the grid.

The Layout Grid

I also included a grid class for showcasing how a grid layout helper could work. Much like the 12-column systems found in CSS frameworks, but funkier. To use it, you simply slap on a grid class on a container. It uses a glorious hack to count the children in pure CSS:

.grid > * { flex: 0 0 calc( round( down, (100% - (1ch build-feed.sh build-index.sh flake.lock flake.nix generate-redirects.sh LICENSE Makefile README.md src target watch.sh (var(--grid-cells) - 1))) / var(--grid-cells), 1ch ) ); } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(1)) { --grid-cells: 1; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(2)) { --grid-cells: 2; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(3)) { --grid-cells: 3; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(4)) { --grid-cells: 4; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(5)) { --grid-cells: 5; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(6)) { --grid-cells: 6; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(7)) { --grid-cells: 7; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(8)) { --grid-cells: 8; } .grid:has(> :last-child:nth-child(9)) { --grid-cells: 9; }Look at it go!

Unlike with tables, the layout grid rows don’t have to fill the width. Depending on your viewport width, you’ll see a ragged right margin. However, by setting flex-grow: 1; on one of the children, that one grows to fill up the remaining width.

The Media Elements

Images and video grow to fill the width. But they have their own proportions, making vertical alignment a problem. How many multiples of the line height should the height of the media be? I couldn’t figure out a way to calculate this with CSS alone.

One option was a preprocessor step that would calculate and set the ratio of every such element as a CSS variable, and then have CSS calculate a padding-bottom based on the ratio and the width:

However, I eventually settled for small chunk of JavaScript to calculate the difference, and set an appropriate padding-bottom. Ending up in JavaScript was inevitable, I suppose.

Summary

There are many small things I haven’t shown in detail, including:

- the debug grid overlay, which you see in the screenshots

- ordered list numbering

- the tree-rendered list

- various form controls and buttons

- the custom

detailselement

But I think I’ve covered the most significant bits. For a full tour, have a look at the source code.

There are still bugs, like alignment not working the same in all browsers, and not working at all in some cases. I’m not sure why yet, and I might try to fix it in at least Firefox and Chromium. Those are the ones I can test with easily.

This has been a fun project, and I’ve learned a bunch of new CSS tricks. Also, the amount of positive feedback has been overwhelming. Of course, there’s been some negative feedback as well, not to be dismissed. I do agree with the concern about legibility. Monospace fonts can be beautiful and very useful, but they’re probably not the best for prose or otherwise long bodies of text.

Some have asked for reusable themes or some form of published artifact. I won’t spend time maintaining such packages, but I encourage those who would. Fork it, tweak it, build new cool things with it!

Finally, I’ll note that I’m happy with how the overall feel of this design turned out, even setting aside the monospace aspect. Maybe it would work with a proportional, or perhaps semi-proportional, font as well?

]]>

In the eternal search of a better text editor, I’ve recently gone back to Neovim. I’ve taken the time to configure it myself, with as few plugins and other cruft as possible. My goal is a minimalist editing experience, tailored for exactly those tasks that I do regularly, and nothing more. In this post, I’ll give a brief tour of my setup and its motivations.

Over the years, I’ve been through a bunch of editors. Here are most of them, in roughly chronological order:

- Adobe Dreamweaver

- Sublime Text

- Atom

- Vim/Neovim

- IntelliJ IDEA

- VS Code

- Emacs

The majority were used specifically for the work I was doing at the time. VS Code for web development, IntelliJ IDEA for JVM languages, Emacs for Lisps. Vim and Emacs have been the most generally applicable, and the ones that I’ve enjoyed the most.

I’ve also evaluated Zed recently, but it hasn’t quite stuck. The start-up time and responsiveness is impressive. However, it seems to insist on being a global application. I want my editor to be local to each project, with the correct PATH from direnv, and I want multiple isolated instances to run simultaneously. Maybe I’ll revisit it later.

Returning to Neovim

Yeah, so I’m back in Neovim. I actually started with the LazyVim distribution based on recommendation. On the positive side, it got me motivated to use Neovim again. But I had some frustrations with the distribution.

The start-up time wasn’t great. I guess it did some lazy loading of plugins to speed things up, but the experience was still that of an IDE taking its time to get ready. Not the Neovim experience I was hoping for.

More importantly, it was full of distractions; popups, status messages, news, and plugins I didn’t need. I guess it takes a batteries-included approach. That might make sense for beginners and those just getting into Neovim, but I realized quickly that I wanted something different.

Supposedly I could strip things out, but instead I decided to start from scratch and build the editor I wanted. One that I understand. Joran Dirk Greef talks about two different types of artists, sculptors and painters, and this is an exercise in painting.

More concretely, my main goals are:

- Plugins

-

I want to keep plugins to an absolute minimum. My editor is meant for coding and writing, and for what I work on right now. I might add or remove plugins and configuration over time, and that’s fine.

- User interface

-

It should be as minimalist as I can make it. Visual distractions kept at a minimum. This includes busy colorschemes, which I find add little value. A basic set of typographical conventions in monochrome works well for me.

- Start-up time

-

With the way I use Neovim, it needs to start fast. I quit and start it all the time, jumping between directories, working on different parts of the system or a project. Often I put it in the background with C-z, but not always. Making it faster seems to be mainly an exercise in minimizing plugins.

I have to mention Nix, you know?

I manage dotfiles and other personal configuration using Nix and home-manager. The Neovim configuration is no exception, so I’ll include some of the Nix bits as well.

The vim.nix module declares that I want Neovim installed and exposed as vim:

In that attribute set, there are two other important parts; the plugins list and the extraConfig.

Plugins

Let’s start with the plugins:

plugins = with pkgs.vimPlugins; [ nvim-lspconfig (nvim-treesitter.withPlugins(p: [ p.bash p.json p.lua p.markdown p.nix p.python p.rust p.zig p.vimdoc ])) conform-nvim neogit fzf-vim ];Basically it’s five plugins, not counting the various treesitter parsers:

- nvim-lspconfig

- LSP is included in Neovim nowadays, but it doesn’t know about specific language servers. The

lspconfigplugins helps with configuring Neovim for use with various servers. - nvim-treesitter

- This provides better highlighting for Neovim. I’ve only included the languages I use right now. No nice-to-haves. I could probably remove this plugin, but I haven’t tried yet.

- conform-nvim

- Auto-formatting is useful and I don’t want to think about it. Of course, I could run

:%!whatever-formatter, but I’d rather have the editor do it for me. - neogit

- Magit was the reason I clung to Emacs for so long. Neogit is, for my purposes, a worthy replacement. It enabled me to finally make the switch.

- fzf-vim

- A wrapper around the awesome fzf fuzzy finder. I use

:Filesand:GFiles, as quick jump-to-file commands (thinkC-pin VS Code or Zed). They are bound to<Leader>ffand<Leader>gf, respectively. This might be another plugin I could do without, writing a small helper aroundfzf, or just making do with:findand**/wildcards. On the other hand, I’m trying out:Buffersinstead of stumbling around with:bnextand:bprev.

One great thing with the Nix setup is I don’t need a package manager in Neovim itself.

Batteries Are Included

Many things I don’t need plugins for. For instance, there are a ton of plugins for auto-completion, but Neovim has most of that built in, and I prefer triggering it manually:

- File name completions with

C-x C-f - Omnicomplete (rebound to

C-Spacein my case) - Buffer completions with

C-x C-n - Spelling suggestions with

C-x C-sorz=

I’ve tried various snippet engines many times, but not found them very useful. Most of my time is spent reading or modifying existing code, not churning out new boilerplate. Instead they tend to clutter the auto-completion list. Snippets might make more sense for things like HTML, but I don’t write HTML often, and in that case I’d prefer some emmet/zen-coding plugin.

You can get great mileage from learning how to use the Quickfix list. I’m no expert, but I prefer investing in composable primitives that I can reuse in different ways. Project-wide search-and-replace is such an example:

:grep whatever :cfdo s/whatever/something else/g | update :cfdo :bdHere we search (:grep, which I’ve configured to use rg), substitute and save each file, and delete those buffers afterwards.

I also use :make and :compiler a lot. Neovim is cool.

Life in Monochrome

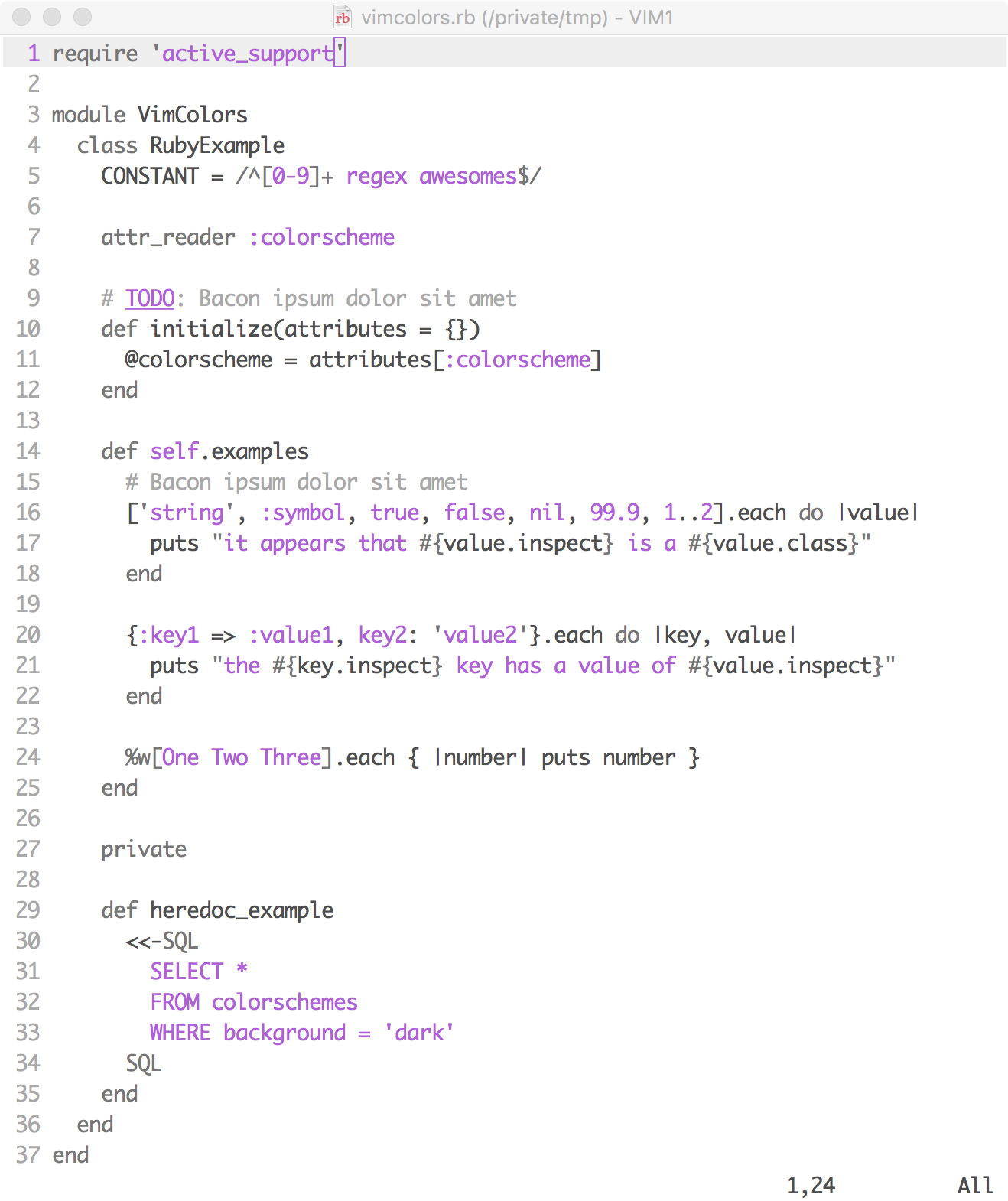

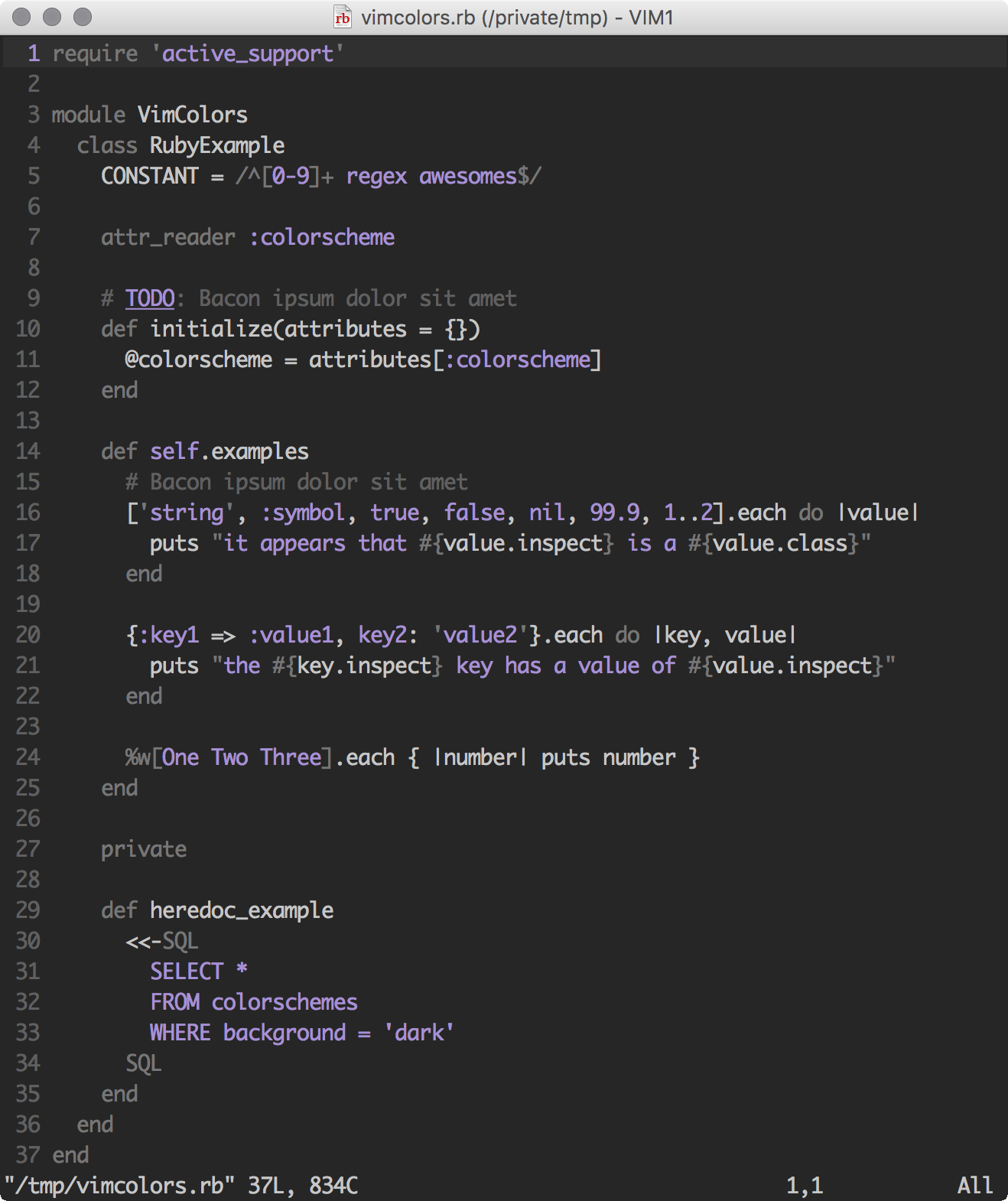

Maybe I’m just growing old, but I prefer a monochrome colorscheme. Right now I’m using the built-in quiet scheme with a few extra tweaks:

set termguicolors set bg=dark colorscheme quiet highlight Keyword gui=bold highlight Comment gui=italic highlight Constant guifg=#999999 highlight NormalFloat guibg=#333333It’s black-and-white, but keywords are bold, comments are darker and italic, and literals are light gray. Here’s how it looks with some Zig code:

Maybe I’m coming off as nostalgic or conservative, but I do find it more readable this way.

Another thing I’m going to try soon is writing on the Daylight Computer, hopefully in Neovim. Being comfortable with a monochrome colorscheme should come in handy.

The Full Configuration

My config uses a Vimscript entrypoint (extraConfig in the Nix code). This part is based on my near-immortal config from the good old Vim days. Early on, it calls vim.loader.enable() to improve startup time. I use Lua scripts for configuring the plugins and related keymap bindings. Maybe everything could be Lua, but I haven’t gotten that far yet. However, it’s nice to have the base config somewhat portable; I can just copy-paste it onto a server or some other temporary environment and have a decent /usr/bin/vim experience.

You’ll find the full configuration in nix.vim and the Lua bits inside the vim/ directory.

That’s about it! I’m really happy with how fast and minimalistic it is. It starts in just above 100ms. And I can understand all of my configuration (even if I don’t understand all of Neovim.) Perhaps I’ve spent more time on it than I’ve saved, but at least I’m happy so far.

I’m writing and publishing this on my birthday. What a treat to find time to blog on such an occasion!

]]>What I’m describing in this post is a trade-off that I find comfortable to use in Python, especially with the new features that I’ll describe. Much of this works nicely in Kotlin and Typescript, too, with minor adaptions.

The principles I try to use are:

- Declarative rather than imperative operations on data

- Transform or fold data using

map,reduce, or for-comprehensions instead of for-loops - Functions with destructuring pattern-matching to dispatch based on data

- Use

whenstatements rather thanif instanceof(...)or inheritance and dynamic dispatch - Programs structured mainly around data and functions

- Programs are trees of function invocations on data, rather than class hierarchies, dependency injection, and overuse of exceptions

- Effects pushed to the outer layers of the program (hexagonal architecture)

- Within reasonable bounds, functions in the guts of programs are pure and return data, whereas the outer layers interpret that data and manage effects (IO, non-determinism, etc)

This list is not exhaustive, but I’m trying to keep this focused. Also, I’m intentionally not taking this in the direction of Haskell, with typeclass hierarchies, higher-kinded types, and so on. I don’t believe cramming such constructs in would benefit Python programs in practice. Furthermore, I won’t be talking about effects and hexagonal architecture in this post.

The examples are all type-annotated and checked with Pyright. You could do all of this without static type-checking, as far as I know.

Finally, note that I consider myself a Python rookie, as I mostly use it for small tools and scripts. The largest program I’ve written in Python is Quickstrom. This post is meant to inspire and trigger new ideas, not to tell anyone how to write Python code.

All right, let’s get started and see what’s possible!

Preliminaries

First, let’s get some boilerplate stuff out of the way. I’m running Python 3.12. Some of the things I’ll show can be done with earlier versions, but not all.

We’ll not be using any external packages, only modules from the standard library:

You might not want to use wildcard imports in more serious programs, but it’s acceptable for these examples.

Pattern Matching

Let’s start with a classic example from the functional programming world: an evaluator for a simple expression-based language. It only supports a few operations in order to keep it simple. First, we the different types of expressions there are using dataclasses and a union type:

type Expr = int | bool | str | BinOp | Let | If @dataclass class BinOp: op: Literal["<"] | Literal[">"] lhs: Expr rhs: Expr @dataclass class Let: name: str value: Expr body: Expr @dataclass class If: cond: Expr t: Expr f: ExprThe syntax for type aliases and the union type operator (|) are both new additions. You could create type aliases before using regular top-level bindings, but mutually recursive types required some types to be enclosed in strings. Otherwise, Python would complain that the second type (e.g. BinOp in the code above) wasn’t defined. It’s a bit cleaner now.

Note that we existing primitive types from Python (int, bool, and str), combined with dataclasses for complex expressions. The str is interpreted as a reference to a name bound in the lexical scope, not as a string literal, as we’ll see in the following snippet.

The evaluator tracks bindings in the Env. Evaluating an expression results in a value that is either an integer or a boolean.

Now, let’s look at the eval function. Here we pattern-match on the expression, which is a union. For literals, we just return the value:

References are looked up in the environment:

Let-bindings create a new environment with the new binding:

Finally, the BinOp and If branches pattern-match on the evaluated nested expressions to make sure they’re of the correct types:

case BinOp(op, lhs, rhs): l = eval(env, lhs) r = eval(env, rhs) match op, l, r: case "<", int(), int(): return l < r case ">", int(), int(): return l > r case _: raise ValueError( f"Invalid binary operation {op} on {lhs} and {rhs}" ) case If(cond, t, f): match eval(env, cond): case True: return eval(env, t) case False: return eval(env, f) case c: raise ValueError(f"Expected bool condition, got: {c}")All right, let’s try it out:

Nice! But this is far from a robust evaluator. If we run it with a deep enough expression, we’d get a RecursionError saying that the maximum recursion depth was exceeded. This is a commonly occurring problem when writing recursive functions in Python.1 The eval function could be rewritten with an explicit stack for operations and operands, but it’s a bit fiddly.

In some cases, you can restructure a recursive function as tail-recursive, and then manually convert it to a loop. Perhaps you could automatically optimize tail-calls, or use a trampoline. Some solutions avoid stack overflows, at the expense of increased heap memory usage. In simpler cases, combinators like map and reduce might suffice, instead of explicit recursion.

Either way, recursive functions and stack overflow is something to watch out for.

Generics

Since Python 3.12, it’s also much nicer to work with generic types. Previously, you had to define type variables before using them in type signatures. This felt very awkward to me.

Let’s look at an example that models a rose tree data type. To spice it up a little, I’m including a map function for both types of the tree nodes. This is equivalent to fmap in Haskell, but without the typeclass and higher-order types.

type RoseTree[T] = Branch[T] | Leaf[T] @dataclass class Branch[A]: branches: list[RoseTree[A]] def map[B](self, f: Callable[[A], B]) -> Branch[B]: return Branch([b.map(f) for b in self.branches]) @dataclass class Leaf[A]: value: A def map[B](self, f: Callable[[A], B]) -> Leaf[B]: return Leaf(f(self.value))Let’s print these trees using pattern matching. Here’s a function that’s written as a loop, maintaining a list of remaining sub-trees to print:

def print_tree[T](tree: RoseTree[T]): trees = [(tree, 0)] while trees: match trees.pop(0): case Branch(branches), level: print(" " * level * 2 + "*") trees = [(branch, level + 1) for branch in branches] + trees case Leaf(value), level: print(" " * level * 2 + "- " + repr(value))It could be even simpler using plain recursion, but then we could run into stack depth issues again. Anyway, let’s try it out:

example = Branch( [ Leaf(1), Leaf(2), Branch([Leaf(3), Leaf(4)]), Branch([Leaf(5), Leaf(6)]), Leaf(7), ] ) >>> print_tree(example.map(str)) * - '1' - '2' * - '3' - '4' * - '5' - '6' - '7'As you can see from the repr being printed, all the values are mapped to strings.

Protocols

As a last example, I’d like to show how you can do basic structural subtyping using protocols. This is useful in cases where you don’t want to define all variants of a union in a single place. For instance, you might have many types of events that can be emitted in an application. Centrally defining each type of event adds unwanted coupling. Breaking apart a base class for events and the code that later on consumes the events decreases cohesion. In such cases, a protocol might be a better option.

We’ll need a new import:

Now, consider the following events in module A:

@dataclass class Increment[Time]: id: str time: Time def description(self: Self) -> str: return "Incremented counter" @dataclass class Reset[Time]: id: str time: Time def description(self: Self) -> str: return "Reset counter"We made them generic just to showcase the combination of protocols and generics. The Time type parameter isn’t instantiated in any other way than datetime in this example.

In another module B — that doesn’t depend on A, and isn’t depended upon by A — the protocol is defined, along with the log_event function:

class Event[Time](Protocol): id: str time: Time def description(self: Self) -> str: ... def log_event(event: Event[datetime]): print(f"Got {event.id} at {event.time}: {event.description()}")Increment and Decrement both implement the Event protocol by virtue of being structurally compatible. They can both be passed to log_event:

If we annotate the Event protocol with @runtime_checkable, we can check it with isinstance and use it in match cases:

@runtime_checkable class Event[Time](Protocol): ... def log(x: Any): match x: case Event() if isinstance(datetime, x.time): log_event(x) case _: print(x)Pretty neat!

That’s all I have for now. Maybe more Python hacking and blog posts will pop up if there’s interest. I’m positive to the evolution of Python and functional programming, as it’s something I use quite regularly.

Join the discussion on Twitter, Hacker News, or Lobsters.

Thank you @tusharisanerd for reviewing a draft of this post.

See On Recursion, Continuations and Trampolines for more in-depth explanations of various solutions to recursive functions and the stack.↩︎

This post focuses on how to use LTL to specify systems in terms of state machines. It’s a brief overview that avoids going into too much detail. For more information on how to test web applications using such specifications, see the Quickstrom documentation.

To avoid possible confusion, I want to start by pointing out that a state machine specification in this context is not the same as a model in TLA+ (or similar modeling languages.) We’re not building a model to prove or check properties against. Rather, we’re defining properties in terms of state machine transitions, and the end goal is to test actual system behavior (e.g. web applications, desktop applications, APIs) by checking that recorded traces match our specifications.

Linear Temporal Logic

In this post, we’ll be using an LTL language. It’s a sketch of a future specification language for Quickstrom.

A formula (plural formulae) is a logical expression that evaluates to true or false. We have the constants:

truefalse

We combine formulae using the logical connectives, e.g:

&&||not==>

The ==> operator is implication. So far we have propositional logic, but we need a few more things.

Temporal Operators

At the core of our language we have the notion of state. Systems change state over time, and we’d like to express that in our specifications. But the formulae we’ve seen so far do not deal with time. For that, we use temporal operators.

To illustrate how the temporal operators work, I’ll use diagrams to visualize traces (sequences of states). A filled circle (●) denotes a state in which the formula is true, and an empty circle (○) denotes a state where the formula is false.

For example, let’s say we have two formulae, P and Q, where:

Pis true in the first and second stateQis true in the second state

Both formulae are false in all other states. The formulae and trace would be visualized as follows:

P ●───●───○ Q ○───●───○Note that in these diagrams, we assume that the last state repeats forever. This might seem a bit weird, but drawing an infinite number of states is problematic.

All of the examples explaining operators have links to the Linear Temporal Logic Visualizer, in which you can interactively experiment with the formulae. The syntax is not the same as in the article, but hopefully that’s not a problem.

Next

The next operator takes a formula as an argument and evaluates it in the next state.

next P ●───○───○ P ○───●───○The next operator is relative to the current state, not the first state in the trace. This means that we can nest nexts to reach further into the future.

next (next P) ●───●───○───○───○ next P ○───●───●───○───○ P ○───○───●───●───○Next for State Transitions

All right, time for a more concrete example, something we’ll evolve throughout this post. Let’s say we have a formula gdprConsentIsVisible which is true when the GDPR consent screen is visible. We specify that the screen should be visible in the current and next state like so:

gdprConsentIsVisible && next gdprConsentIsVisibleA pair of consecutive states is called a step. When specifying state machines, we use the next operator to describe state transitions. A state transition formula is a logical predicate on a step.

In the GDPR example above, we said that the consent screen should stay visible in both states of the step. If we want to describe a state change in the consent screen’s visibility, we can say:

gdprConsentIsVisible && next (not gdprConsentIsVisible)The formula describes a state transition from a visible to a hidden consent screen.

Always

But interesting state machines usually have more than one possible transition, and interesting behaviors likely contain multiple steps.

While we could nest formulae containing the next operator, we’d be stuck with specifications only describing a finite number of transitions.

Consider the following, where we like to state that the GDPR consent screen should always be visible:

gdprConsentIsVisible && next (gdprConsentIsVisible && next ...)This doesn’t work for state machines with cycles, i.e. with possibly infinite traces, because we can only nest a finite number of next operators. We want state machine specifications that describe any number of transitions.

This is where we pick up the always operator. It takes a formula as an argument, and it’s true if the given formula is true in the current state and in all future states.

always P ●───●───●───●───● P ●───●───●───●───● always Q ○───○───●───●───● Q ●───○───●───●───●Note how always Q is true in the third state and onwards, because that’s when Q becomes true in the current and all future states.

Let’s revisit the always-visible consent screen specification. Instead of trying to nest an infinite amount of next formulae, we instead say:

always gdprConsentIsVisibleNeat! This is called an invariant property. Invariants are assertions on individual states, and an invariant property says that it must hold for every state in the trace.

Always for State Machines

Now, let’s up our game. To specify the system as a state machine, we can combine transitions with disjunction (||) and the always operator. First, we define the individual transition formulae open and close:

let open = not gdprConsentIsVisible && next gdprConsentIsVisible; let close = gdprConsentIsVisible && next (not gdprConsentIsVisible);Our state machine formula says that it always transitions as described by open or close:

always (open || close)We have a state machine specification! Note that this specification only allows for transitions where the visibility of the consent screen changes back and forth.

So far we’ve only seen examples of safety properties. Those are properties that specify that “nothing bad happens.” But we also want to specify that systems somehow make progress. The following two temporal operators let us specify liveness properties, i.e. “good things eventually happen.”

Quickstrom does not support liveness properties yet.1

Eventually

We’ve used next to specify transitions, and always to specify invariants and state machines. But we might also want to use liveness properties in our specifications. In this case, we are not talking about specific steps, but rather goals.

The temporal operator eventually takes a formula as an argument, and it’s true if the given formula is true in the current or any future state.

eventually P ○───○───○───○───○ P ○───○───○───○───○ eventually Q ●───●───●───●───○ Q ○───○───○───●───○For instance, we could say that the consent screen should initially be visible and eventually be hidden:

gdprConsentIsVisible && eventually (not gdprConsentIsVisible)This doesn’t say that it stays hidden. It may become visible again, and our specification would allow that. To specify that it should stay hidden, we use a combination of eventually and always:

gdprConsentIsVisible && eventually (always (not gdprConsentIsVisible))Let’s look at a diagram to understand this combination of temporal operators better:

eventually (always P) ○───○───○───○───○ P ○───○───●───●───○ eventually (always Q) ●───●───●───●───● Q ○───○───●───●───●The formula eventually (always P) is not true in any state, because P never starts being true forever. The other formula, eventually (always Q), is true in all states because Q becomes true forever in the third state.

Until

The last temporal operator I want to discuss is until. For P until Q to be true, P must be true until Q becomes true.

P until Q ●───●───●───●───○ P ●───●───○───○───○ Q ○───○───●───●───○Just as with the eventually operator, the stop condition (Q) doesn’t have to stay true forever, but it has to be true at least once.

The until operator is more expressive than always and eventually, and they can both be defined using until.2

Anyway, let’s get back to our running example. Suppose we have another formula supportChatVisible that is true when the support chat button is shown. We want to make sure it doesn’t show up until after the GDPR consent screen is closed:

not supportChatVisible until not gdprConsentIsVisibleThe negations make it a bit harder to read, but it’s equivalent to the informal statement: “the support chat button is hidden at least until the GDPR consent screen is hidden.” It doesn’t demand that the support chat button is ever visible, though. For that, we instead say:

gdprConsentIsVisible until (supportChatVisible && not gdprConsentIsVisible)In this formula, supportChatVisible has to become true eventually, and at that point the consent screen must be hidden.

Until for State Machines

We can use the until operator to define a state machine formula where the final transition is more explicit.

Let’s say we want to specify the GDPR consent screen more rigorously. Suppose we already have the possible state transition formulae defined:

allowCollectedDatadisallowCollectedDatasubmit

We can then put together the state machine formula:

let gdprConsentStateMachine = gdprConsentIsVisible && (allowCollectedData || disallowCollectedData) until (submit && next (not gdprConsentIsVisible));In this formula we allow any number of allowCollectedData or disallowCollectedData transitions, until the final submit resulting in a closed consent screen.

What’s next?

We’ve looked at some temporal operators in LTL, and how to use them to specify state machines. I’m hoping this post has given you some ideas and inspiration!

Another blog post worth checking out is TLA+ Action Properties by Hillel Wayne. It’s written specifically for TLA+, but most of the concepts are applicable to LTL and Quickstrom-style specifications.

I intend to write follow-ups, covering atomic propositions, queries, actions, and events. If you want to comment, there are threads on GitHub, Twitter, and on Lobsters. You may also want to sponsor my work.

Thank you Vitor Enes, Andrey Mokhov, Pascal Poizat, and Liam O’Connor for reviewing drafts of this post.

Edits

- 2021-05-28: Added links to the Linear Temporal Logic Visualizer matching the relevant examples. Note that the syntax is different in the visualizer.

Footnotes

What is Quickstrom?

Quickstrom is a new autonomous testing tool for the web. It can find problems in any type of web application that renders to the DOM. Quickstrom automatically explores your application and presents minimal failing examples. Focus your effort on understanding and specifying your system, and Quickstrom can test it for you.

Past and future

I started writing Quickstrom on April 2, 2020, about a week after our first child was born. Somehow that code compiled, and evolved into a capable testing tool. I’m now happy and excited to share it with everyone!

In the future, when Quickstrom is more robust and has a greater mileage, I might build a commercial product on top of it. This one of the reasons I’ve chosen an AGPL-2.0 license for the code, and why contributors must sign a CLA before pull requests can be merged. The idea is to keep the CLI test runner AGPL forever, but I might need a license exception if I build a closed-source SaaS product later on.

Learning more

Interested in Quickstrom? Start by checking out any of these resources:

- Main website

- Project documentation, including installation instructions and usage guides

- Source code

And keep an eye out for updates by signing up for the newsletter, or by following me on Twitter. Documentation should be significantly improved soon.

Comments

If you have any comments or questions, please reply to any of the following threads:

]]>WebCheck

During the last three months I’ve used my spare time to build WebCheck. It’s a browser testing framework combining ideas from:

- property-based testing (PBT)

- TLA+ and linear temporal logic

- functional programming

In WebCheck, you write a specification for your web application, instead of manually writing test cases. The specification describes the intended behavior as a finite-state machine and invariants, using logic formulae written in a language inspired by the temporal logic of actions (PDF) from TLA+. WebCheck generates hundreds or thousands of tests and runs them to verify if your application is accepted by the specification.

The tests generated by WebCheck are sequences of possible actions, determined from the current state of the DOM at the time of each action. You can think of WebCheck as exploring the state space automatically, based on DOM introspection. It can find user behaviors and problems that we, the biased and lazy humans, are unlikely to think of and to write tests for. Our job is instead to think about the requirements and to improve the specification over time.

Specifications vs Models

In property-based testing, when testing state machines using models, the model should capture the essential complexity of the system under test (SUT). It needs to be functionally complete to be a useful oracle. For a system that is conceptually simple, e.g. a key-value database engine, this is not a problem. But for a system that is inherently complex, e.g. a business application with a big pile of rules, a useful model tends to grow as complex as the system itself.

In WebCheck, the specification is not like such a model. You don’t have to implement a complete functional model of your system. You can leave out details and specify only the most important aspects of your application. As an example, I wrote a specification that states that “there should at no time be more than one spinner on a page”, and nothing else. Again, this is possible to specify in PBT in general, but not with model-based PBT, from what I’ve seen.

TodoMVC as a Benchmark

Since the start of this project, I’ve used the TodoMVC implementations as a benchmark of WebCheck, and developed a general specification for TodoMVC implementations. The TodoMVC contribution documentation has a high-level feature specification, and the project has a Cypress test suite, but I was curious if I could find anything new using WebCheck.

Early on, checking the mainstream framework implementations, I found that both the Angular and Mithril implementations were rejected by my specification, and I submitted an issue in the TodoMVC issue tracker. Invigorated by the initial success, I decided to check the remaining implementations and gradually improve my specification.

I’ve generalized the specification to work on nearly all the implementations listed on the TodoMVC website. Some of them use the old markup, which uses IDs instead of classes for most elements, so I had to support both variants.

The Specification

Before looking at the tests results, you might want to have a look at the WebCheck specification that I’ve published as a gist:

The gist includes a brief introduction to the WebCheck specification language and how to write specifications. I’ll write proper documentation for the specification language eventually, but this can give you a taste of how it works, at least. I’ve excluded support for the old TodoMVC markup to keep the specification as simple as possible.

The specification doesn’t cover all features of TodoMVC yet. Most notably, it leaves out the editing mode entirely. Further, it doesn’t cover the usage of local storage in TodoMVC, and local storage is disabled in WebCheck for now.

I might refine the specification later, but I think I’ve found enough to motivate using WebCheck on TodoMVC applications. Further, this is likely how WebCheck would be used in other projects. You specify some things and you leave out others.

The astute reader might have noticed that the specification language looks like PureScript. And it pretty much is PureScript, with some WebCheck-specific additions for temporal modalities and DOM queries. I decided not to write a custom DSL, and instead write a PureScript interpreter. That way, specification authors can use the tools and packages from the PureScript ecosystem. It works great so far!

Test Results

Below are the test results from running WebCheck and my TodoMVC specification on the examples listed on the TodoMVC website. I’ll use short descriptions of the problems (some of which are recurring), and explain in more detail further down.

| Example | Problems/Notes | |

|---|---|---|

| Pure JavaScript | ||

| ✓ | Backbone.js | |

| ❌ | AngularJS |

|

| ✓ | Ember.js | |

| ✓ | Dojo | |

| ✓ | Knockback | |

| ✓ | CanJS | |

| ✓ | Polymer | |

| ✓ | React | |

| ❌ | Mithril |

|

| ✓ | Vue | |

| ✓ | MarionetteJS | |

| Compiled to JavaScript | ||

| ✓ | Kotlin + React | |

| ✓ | Spine | |

| ✓ | Dart | |

| ✓ | GWT | |

| ✓ | Closure | |

| ✓ | Elm | |

| ❌ | AngularDart |

|

| ✓ | TypeScript + Backbone.js | |

| ✓ | TypeScript + AngularJS | |

| ✓ | TypeScript + React | |

| ✓ | Reagent | |

| ✓ | Scala.js + React | |

| ✓ | Scala.js + Binding.scala | |

| ✓ | js_of_ocaml | |

| – | Humble + GopherJS |

|

| Under evaluation by TodoMVC | ||

| ✓ | Backbone.js + RequireJS | |

| ❌ | KnockoutJS + RequireJS |

|

| ✓ | AngularJS + RequireJS |

|

| ✓ | CanJS + RequireJS | |

| ❌ | Lavaca + RequireJS |

|

| ❌ | cujoJS |

|

| ✓ | Sammy.js | |

| – | soma.js |

|

| ❌ | DUEL |

|

| ✓ | Kendo UI | |

| ❌ | Dijon |

|

| ✓ | Enyo + Backbone.js | |

| ❌ | SAPUI5 |

|

| ✓ | Exoskeleton | |

| ✓ | Ractive.js | |

| ✓ | React + Alt | |

| ✓ | React + Backbone.js | |

| ✓ | Aurelia | |

| ❌ | Angular 2.0 |

|

| ✓ | Riot | |

| ✓ | JSBlocks | |

| Real-time | ||

| – | SocketStream |

|

| ✓ | Firebase + AngularJS | |

| Node.js | ||

| – | Express + gcloud-node |

|

| Non-framework implementations | ||

| ❌ | VanillaJS |

|

| ❌ | VanillaJS ES6 |

|

| ✓ | jQuery | |

✓ Passed, ❌ Failed, – Not testable

- Filters not implemented

-

There’s no way of switching between “All”, “Active”, and “Completed” items. This is specified in the TodoMVC documentation under Routing.

- Race condition during initialization

-

The event listeners are attached some time after the

.new-todoform is rendered. Although unlikely, if you’re quick enough you can focus the input, press Return, and post the form. This will navigate the user agent to the same page but with a query parameter, e.g.index.html?text=. In TodoMVC it’s not the end of the world, but there are systems where you do not want this to happen. - Inconsistent first render

-

The application briefly shows an inconsistent view, then renders the valid initial state. KnockoutJS + RequireJS shows an empty list items and “0 left” in the bottom, even though the footer should be hidden when there are no items.

- Needs a custom

readyWhencondition -

The specification awaits an element matching

.todoapp(or#todoappfor the old markup) in the DOM before taking any action. In this case, the implementation needs a modified specification that instead awaits a framework-specific class, e.g..ng-scope. This is an inconvenience in testing the implementation using WebCheck, rather than an error. - No input field

-

There’s no input field to enter TODO items in. I’d argue this defeats the purpose of a TODO list application, and it’s indeed specified in the official documentation.

- Adds pending item on other interaction

-

When there’s a pending item in the input field, and another action is taken (toggle all, change filter, etc), the pending item is submitted automatically without a Return key press.

.todo-count strongelement is missing-

An element matching the selector

.todo-count strongmust be present in the DOM when there are items, showing the number of active items, as described in the TodoMVC documentation. - State cannot be cleared

-

This is not an implementation error, but an issue where the test implementation makes it hard to perform repeated isolated testing. State cannot (to my knowledge) be cleared between tests, and so isolation is broken. This points to a key requirement currently placed by WebCheck: the SUT must be stateless, with respect to a new private browser window. In future versions of WebCheck, I’ll add hooks to let the tester clear the system state before each test is run.

- Missing/broken link

-

The listed implementation seems to be moved or decommissioned.

Note that I can’t decide which of these problems are bugs. That’s up to the TodoMVC project maintainers. I see them as problems, or disagreements between the implementations and my specification. A good chunk of humility is in order when testing systems designed and built by others.

The Future is Bright

I’m happy with how effective WebCheck has been so far, after only a few months of spare-time prototyping. Hopefully, I’ll have something more polished that I can make available soon. An open source tool that you can run yourself, a SaaS version with a subscription model, or maybe both. When that time comes, maybe WebCheck can be part of the TodoMVC project’s testing. And perhaps in your project?

If you’re interested in WebCheck, please sign up for the newsletter. I’ll post regular project updates, and definitely no spam. You can also follow me on Twitter.

Comments

If you have any comments or questions, please reply to any of the following threads:

Thanks to Hillel Wayne, Felix Holmgren, Martin Janiczek, Tom Harding, and Martin Clausen for reviewing drafts of this post.

]]>This tutorial was originally written as a book chapter, and later extracted as a standalone piece. Since I’m not expecting to finish the PBT book any time soon, I decided to publish the chapter here.

System Under Test: User Signup Validation