| CARVIEW |

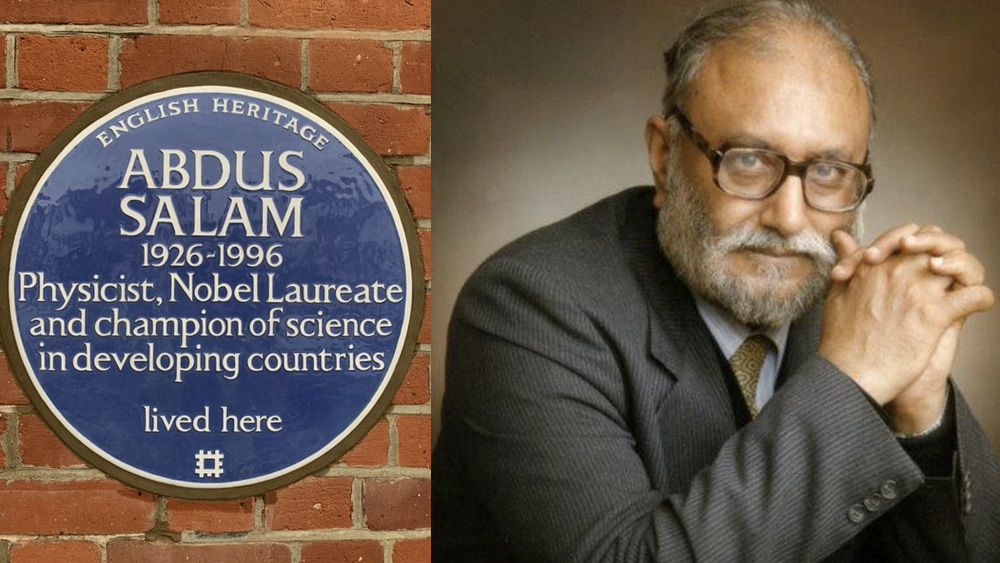

Today English Heritage unveils a new blue plaque to the theoretical physicist and Nobel Laureate Abdus Salam (1926-1996), with an appeal for more nominations for scientists to increase their representation in the London scheme. As a historian of science sitting on their Blue Plaque panel, I am delighted to support this call.

Scientists and natural philosophers account for around 15% of the more than 950 blue plaques in London. Some of these will be found categorised under medicine or engineering but the scheme lists just 66 plaques online under the category of science, in contrast to 102 as fine arts, 171 politics and 213 literature. These numbers are a product of the scheme’s earlier history, under the Society of Arts, London County Council and Greater London Council, as well as of broader cultural assumptions about who and what should receive such marks of public esteem.

The contributors to science honoured by blue plaques include key figures of the 17th-century Royal Society, Isaac Newton and Christopher Wren, as well as household names such as Charles Darwin and Alan Turing. But our understanding of science suffers if it encourages an assumption that its progress has been due only to a few geniuses, usually white and male, and often seen as working in isolation from society.

Happily, this scheme also recognises a whole range of other contributors and contributions. One plaque marks the Holborn site of the shop and workshop of the watchmaker Thomas Earnshaw, another the home of the Scottish plant collector and ‘tea thief’ Robert Fortune, and in Hackney we find a plaque to the zoologist Philip Gosse. The new plaque to Salam reminds us that not all eminent contributors to science in London were white or born in the west.

There are also, especially after recent calls for nominations, several plaques marking women scientists. These include the increasingly celebrated figures of Ada Lovelace and Rosalind Franklin but also a number whose plaques should help them to be more widely recognised, such as the botanists Agnes Arber and Helen Gwyenne-Vaughan and the electrical engineer and physicist Hertha Ayrton.

One of the distinctive features of the scheme is that a building associated with a nominated figure should still survive. While this limits who can be put forward, it has the benefit of encouraging us to think about these individuals in context – not just as those who contributed ideas and information to their scientific field, but as people who lived and worked, loved, laughed and prayed, across London’s boroughs. Science is a human endeavour that is not, and never has been, isolated from place.

The biases of building survival, as well as the wealth and connections that are often prerequisites for success, mean that many blue plaques are found on substantial buildings in places like Westminster, Kensington and Chelsea. But we find that other locations and a wide variety of stories are revealed by these combined markers of place and people.

Abdus Salam’s plaque is on a red-brick Edwardian house in Putney, his London base from 1957 until his death in 1996. While the wording of the plaque tells of his international fame and role in championing science in developing countries, the location is residential, a home where he studied and wrote, and listened to music and Quranic verses on his record player.

The very first plaque to a scientific figure, unveiled by the Society of Arts in 1876, is in Marylebone. It celebrates Michael Faraday (1791-1867), known for his discoveries in electromagnetism at the Royal Institution. However, the plaque records that he was ‘Apprentice here’, for the building is where he worked not as a chemist but as a bookbinder. His apprenticeship moved him from Newington Butts in Surrey to a building from which he could attend scientific lectures.

In Hackney, though sadly not currently visible from the street, there is a plaque to Joseph Priestley (1733-1804). A chemist, best known for his discovery of gases, including Oxygen, Priestley was also a teacher and preacher. His plaque, calling him ‘Scientist, Philosopher and Theologian’, tells us that this was the site of the Gravel Pit Meeting, a nonconformist religious congregation to which Priestley was minster.

While Priestley’s is one of the wordier plaques, it is another man of science who has one of the most evocative. This is Luke Howard (1722-1864), described as ‘Namer of Clouds’. He was the amateur meteorologist who proposed the classification and Latin names for clouds. He was also a manufacturing chemist of means, whose plaque is at 7 Bruce Grove in Tottenham. Now owned by developers it is currently vacant and at risk, with campaigners hoping to save it from further deterioration. As the site of Tottenham’s only blue plaque, and a Grade II listed building, it would be a tragedy to lose Howard’s former home.

English Heritage, and the Blue Plaque panel, rely on the public to make proposals for plaques such as these. They particularly welcome those that help reveal the significant stories that link scientists and London’s buildings.

]]>Edinburgh to Hawai’i: the short astronomical career of John Walter Nichol

20 November 2020, 19:30-21:00 – Free

The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh (via Zoom for members; visitors can watch live via their YouTube channel): further details here.

The name John Walter Nichol enters the history of astronomy for his participation as an observer in one of the British expeditions to observe the transit of Venus in 1874. He was said to have been an assistant at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, but little else has been added; he was just one of the small army of observers mobilised that year. He is, however, brought to life in the caricatures that another member of his expeditionary team produced to record their ‘Life and Adventures’ on expedition. These prompted me to find out more: what brought this Edinburgh native to astronomy and to Hawai’i, and where did he go next?

]]>Expeditionary Astronomers: the 1769 Transit of Venus and British Voyages of Scientific Exploration, at the Royal Astronomical Society on 11 October 2019 (30 minutes).

Mathematical Practice and 18th-Century British Voyages of Scientific Exploration, at the Museum of London for the annual Gresham College Lecture of the British Society for the History of Mathematics on 23 October 2019 (45 minutes).

Arber, born Agnes Robertson, researched the physical forms and microscopic structures of living and fossil plants, publishing some seventy scientific articles and eight books over a long career. She investigated several plant families, including cereals and grasses, seed-producing and flowering plants, and their places within taxonomy and evolutionary history. In her sixties she became the first woman to win the medal of the Linnaean Society and the third to be a fellow of the Royal Society.

She wrote, in 1916, that should an alien visit Earth it might think of science as “some elixir which could be bought for hard cash and which would ensure salvation to any nation obtaining it in sufficient quantities.” She nevertheless saw good research as “an expression of the personality” of the scientist.

While part of the shift to a more experimental approach to botany, Arber was distinctive in also drawing on philosophy and history. These were fields she contributed to in their own right, particularly on the nature and origins of biological research. Her book Herbals, their Origin and Evolution remains a standard, and an admiring obituarist wrote of her “breadth of outlook, philosophical insight, profound learning, and meticulous attention to detail”. Her work remains of interest to 21st-century developmental botanists, philosophers and historians.

Arber lived in Cambridge for most of her career but the London links required for Blue Plaque recognition are also strong. She was born there and attended the academically ambitious North London Collegiate School for Girls (NLC), then sited off Camden Road, where she met old girl, Ethel Sargant, in whose home laboratory she began botanical research. It was in London, too, that Arber gained a first-class degree at University College, London, later returning to hold the Quain Studentship, gain her doctorate, work as a teaching assistant and, in 1908, lecturer.

Between her two UCL degrees, Arber attended Cambridge University, having won an entrance scholarship to Newnham College in 1899. She, again, achieved a first-class marks but, as a woman, was not awarded a degree. Nevertheless she returned to Cambridge the year after her appointment at UCL, on her marriage to the paleobotanist Edward A. Newell Arber. He had, apparently, enticed her to move by suggesting “that life in Cambridge offered unique opportunities for the observation of river and fenland plants.”

In Cambridge Arber was allowed space within Newnham College’s Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women, founded in 1884. She worked largely unfunded and after the Balfour closed in 1927 no satisfactory alternative space or position was found and she set up a laboratory at home. Her husband had died in 1918, leaving her to raise their six-year-old. Arber could, however, afford domestic help and her daughter remembered that her mother “snatched time from her writing to do the necessary minimum of domestic things” rather than vice versa.

Arber’s career was marked by an outstanding published output and much recognition but was also significantly shaped by the limited nature of the opportunities available. It was not until 1945 that any woman became a fellow of the Royal Society and only in 1948 that Cambridge University condescended to award degrees to women. Where routes were opening up, Arber took advantage.

She was the beneficiary of the determined efforts of women such as Frances Buss (founder of the NLC) and Emily Davies (founder of Girton College, Cambridge) to create establishments for girls’ and women’s education, including in the sciences, and to campaign for their right to university degrees and political representation. A generation earlier she would not have been able to gain degrees in London or work within a Cambridge laboratory.

However, the difficulties and need for careful career management are also clear. Family support and connections were essential, as were networks of female mentorship and collegiate encouragement. The fact that Aber was able to learn key techniques from Ethel Sargant was hugely important as, undoubtedly, was the community of women within the Balfour Laboratory and among the mixed attendance of meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS), where Arber was active for many years.

The limits to her career are typical. She followed her husband to Cambridge, losing a professional position and influential colleagues at UCL. It was reported to be a happy marriage, and family trips helped inspire the couple’s daughter Muriel Agnes Arber to a geological career, but one wonders what Arber might have achieved had she remained in London. She could afford, and came to enjoy, life as a lone researcher but her career suffered because she did not, as the botanist F.O. Bower put it, “occupy a scientific position of note”.

The sense of women gaining just so much and no more is well illustrated by Arber’s career within the BAAS. Like other women, Arber found an opportunity here that was closed elsewhere. In 1921 she was made the botany section’s president only to then be persuaded to resign in the face of male botanists finding it “not agreeable” to have one female president directly follow another, Edith Rebecca Saunders having taken the role in 1920.

Such dynamics are, necessarily, under consideration when the Blue Plaque Panel deliberates nominations. Judging the significance and reputation of individuals within groups that were systematically denied opportunities – and, indeed, of those with every privilege that made a career in the public eye almost inevitable – is difficult.

The scheme was founded in 1866 and, predictably, the proportion of women honoured in its early decades was not high. It is still not high enough, partly because of this history; of the more than 900 plaques just 129 (around 14%) are for women. A sign of the slowly changing times is that nearly two-thirds of those went up after 1986, when English Heritage took over the scheme.

Recently the scheme has called for, welcomed and generated its own nominations for individuals from under-represented groups that meet the scheme’s criteria. Since a 2016 appeal for nominations, the Panel has for the first time been able to shortlist more women than men (51%), though the wait for permissions and annual schedule of unveilings means it will take time for this to translate into new plaques.

For a while yet, then, the proportion of plaques to women will remain less than ideal, meaning that commentators will – quite rightly – keep raising the issue. We rely on members of the public to continue to help by putting forward nominations. There is more work to be done: make your suggestions here.

Further reading: Kathryn Packer, ‘A laboratory of one’s own: the life and works of Agnes Arber, FRS, 1879–1960’, Notes and Records of the Royal Society, 51 (1997), 87–104.

]]>

Ackermann, Silke, Kremer, Richard L., and Miniati, Mara, Scientific Instruments on Display. Leiden: Brill, 2014. Pp. xxxiv + 231. ISBN 978-90-04-26439-7. £88 (hardback).

The twelve chapters in this volume are drawn from papers given at the 2010 Scientific Instrument Symposium, which met in the newly renovated Museo Galileo and took the theme “Instruments on Display”. Some of the contributions are fairly slight in length and analysis, but together they encourage “thinking about the cultural, technical or scientific significance of how scientific instruments have been displayed in venues other than those for which they were originally made”, even if they do not quite lead to “general frameworks” for such thoughts (p. xvii). The usefulness of the collection is in its variety. “Display” and “instruments” are interpreted broadly, generating a plurality of meanings that reflect changing views of science, instruments, the public, museums and markets. Instruments rather rarely appear as tools but are, instead, commodities, relics, adornments, scenery and means of educating or conveying national, cultural, institutional, scientific or technical histories. Likewise, while “display” often relates to museum galleries and exhibitions, it also points to schoolrooms, laboratories, observatories, showrooms, theatres, cinemas, books and portraits.

The book opens with its longest chapter: Marco Beretta on the Museo di Storia della Scienza (now Museo Galileo) in Florence and its founder and champion Andrea Corsini. Drawing on the museum’s archives, including photographs of early displays, we see the manoeuvring required to develop this “shrine to science” (p. 4), for scholarly study and public edification. Beretta reveals Corsini’s labours, competing schemes that threatened them and the development of the displays. We learn that Corsini had an international scholarly correspondence, and it would have been interesting to pursue the question of cross-national similarities and differences. Why was the early twentieth century a key moment, across Europe and the US, for historic scientific instrument collections, but, also, what was specific to Italy and Florence? Beretta is anxious to absolve Corsini of association with fascism, but rather passes over Mussolini’s opening of the museum and the fact that its “most steadfast patron”, Prince Piero Ginori Conti, was a “convinced supporter” (p. 22). Surely these things influenced the museum’s presentation of scientific instruments.

The theme of individual passion as the motivating force behind instrument displays is evident elsewhere. The Paris Observatory’s display of its “patrimonial collections”, discussed by Laurence Bobis and Suzanne Débarbat, was about institutional identity but required individual directors to value defunct instruments, displays and public interest. The university displays discussed by Steven Turner and Richard Paselk were absolutely reliant on individuals. Turner describes Chicago’s Science Teaching Museum, a “Demonstration Laboratory” set up by physics professor Harvey B. Lemon, which gained admiration and imitators but closed when he resigned. Paselk is the “guardian angel” (p. 148) of Humboldt State University’s scientific instruments museum, as collector, curator and fundraiser. His chapter, describing its genesis and development, reinforced by an early online presence, gives insight into the collectors’ role, although it might helpfully have raised questions of motivation and meaning.

The chapters by Alison Boyle, Richard Dunn and Silke Ackermann form a useful group. They focus on three major London institutions – the Science Museum (SM), the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and the British Museum (BM) – and chart changes to the city’s museological landscape and the identities of each institution. Similar instruments could be displayed in each for significantly different purposes, illustrating scientific principles, the techniques of applied art or aspects of cultural history. However, internal changes and conflicts also played out in displays and floor plans that reflect the views of directors, curators, scientists, educators or industrial partners. As Boyle shows, the SM’s purpose of educating the public about modern science has often sat awkwardly with its role as a custodian of historical collections. In Florence, instruments were collected as relics and historical artefacts, but at the SM they often became so only accidentally, as time passed and as curators moved away from presenting modern science through linear sequences of instrumental development. The result has been “akin to two different institutions – a science museum and a science centre – sharing space within one building.” (p. 54).

As Dunn writes, the SM and V&A are “two very different institutions with a common origin” (p. 61). Scientific instruments have formed a small but persistent part of the latter’s collections, not to illustrate principles or histories of scientific disciplines but as examples of the applied arts. Their function was largely irrelevant, with focus instead on materials, techniques and decoration. However, the V&A’s increasingly historical approach has encouraged attention to instruments’ uses, relating to domesticity or fashion as much as science and knowledge. This brings V&A’s recent displays close to those of the BM, as described by Ackermann. While its eighteenth-century founders might aspire to an encyclopaedic collection, subsequently, and with the foundation of other museums, the presence of scientific artefacts raised questions and required justification. Today, however, they are seen as being one aspect of wider cultures: they “naturally take their place” alongside other objects associated with a particular time and location (p. 92).

A common complaint regarding modern museum displays is that they include relatively few objects. Curators could, however, take inspiration from other kinds of presentation described here, which are as historically specific as, say, recreated laboratories. There are, for example, the dense displays created by instrument manufacturers for world expositions, as described by Richard Kremer, in his chapter on the United States Centennial Exhibition, and by Peggy Kidwell and Amy Ackerberg-Hastings, as part of their chapter on the various contexts of slide rule display. Even the most humble instruments could be made aesthetically pleasing when arranged, en mass, in geometric patterns. Inga Elmqvist Söderlund likewise shows how instruments could be displayed as enticing commodities and objects of desire in seventeenth-century frontispieces.

As Ingrid Jendrzejewski’s chapter on seventeenth-century theatrical productions reminds us, however, in different contexts instruments can be objects of ridicule. Telescopes quickly moved from novelty requiring exposition to recognised resource for metaphor and humour, symbolising deception, lack of perspective or a failure to take up accepted social roles. “[M]ost characters who carried telescopes on the seventeenth-century stage were not meant to be taken seriously” (p. 179). Jendrzejewski’s examples include instruments being evoked verbally and stage directions requiring actors to carry or manipulate “all manner of Mathematical Instruments” (p. 183). It would be fascinating to know more about such props: were they real instruments, or based on them, and what were audiences presumed to recognise? They were, undoubtedly, a long way from the realistic props and scenery required in film, discussed in the short contribution from Ileana Chinnici, Donatella Randazzo and Fausto Casi. Remarkably, the 1963 film of The Leopard featured antique instruments once owned by Prince Giulio Fabrizio Tomasi, the inspiration for the story’s main character.

Given the visual and material focus, it is good that each chapter is well illustrated. Collectively, the images are suggestive of changes over time and the broad ways in which the theme can be interpreted. They form a provocative source that, along with the case studies, can be put to use by scholars interested in the history of science, scientific instruments, material culture, museums and the history of science in public. It joins a growing literature that reveals a desire to bring such studies together to their mutual benefit.

]]>

Govoni, Paola, and Franceschi, Zelda Alice (eds.), Writing about Lives in Science: (Auto)Biography, Gender, and Genre. Goettingen: V&R Unipress, 2015. Pp. 287. ISBN. 978-3-8471-0263-2. €44.99 (hardback).

Biography within the history of science has repeatedly been rescued, revived and reconsidered: from Thomas Hankins’s 1979 ‘Defense of Biography’, to the essays in Telling Lives in Science (1996, eds. Michael Shortland and Richard Yeo), the 2002 workshop that led to The History and Poetics of Scientific Biography (2006, ed. Thomas Söderqvist), the 2006 ‘Focus’ section in Isis and now this collection. Many of those who have written biographies have been reflexive about their motivations and their version of their subject’s life and character. Richard Westfall, for example, produced some fascinating reflections for the 1985 collection Introspection in Biography, showing the wisdom of B.J.T. Dobbs’s comment that Newton is “something of a Rorschach inkblot test” for historians (Isis 85 (1994), 516). Those academic biographies of major figures have, after all, still been produced and, as Margaret Rossiter and Pnina G. Abir-Am led the way from the 1980s onward, so too have collections and considerations of lives of women scientists.

Thus, while it may be true, as Paola Govoni says in the introduction to this collection, that historians of science “seem to suffer from a certain uneasiness when faced with biography as a genre” (p. 8), that uneasiness has resulted in plenty of words. This book adds to them but helpfully brings together various strands to remind us of: the usefulness of biographical approaches to understanding the social and cultural worlds of science; the important insight provided by the self-reflections of historians and biographers; and the biography’s role in shaping views of what it means to live a life in science. While this last point has been made in a number of previous studies, several chapters in this collection bring home forcefully the importance of scholarship that brought women’s lives in science to light. Abir-Am’s chapter on women scientists of the 1970s in particular reveals the difficulties and impossibilities of those lives, which we must grasp if the still present “leaky pipeline” of women’s careers is ever to be mended.

Thus, although, as Paula Findlen writes, professional historians of science may have avoided biography as “too heroic, too isolating and idolizing of the individual” (p. 92), we might feel sympathy for those whose writings have done a little championing, as well as gratitude to those who did the spadework to save these lives from further oblivion, whether 20th-century feminists and women scientists or the 18th-century compilers of biographical dictionaries discussed in Findlen’s chapter. This book is, then, as much an account of gender history in relation to history of science as of biography, although it demonstrates the importance of the biographical genre for women’s history, and the direct links with campaigns for equality. The first three brief introspective chapters on biographical writing and its reception (Evelyn Fox Keller and Georgina Ferry) and gender history (Londa Schiebinger), all reflect contemporary gender politics in science and/or academia, and the authors’ sense of the “imperative” (p. 43) to address this in their work. They are, as Zelda Alice Franceschi writes in her Afterword, “women who have taken a stand” (p. 267).

As is often the way with collected volumes, there is some repetition – in particular discussions of the attitude within professional history of science to biography or to gender studies – and some unevenness. The chapters range from autobiographical reflection on writing biography to analysis of historical biographies and demonstrations of a modern biographical approach. They vary in length, structure and readability but tend to cluster their historical focus. There is particular attention to the 18th century – with discussions of the lives of Laura Bassi and other women of Enlightenment science by Marta Cavassa, Findlen, Massimo Mazzotti and Schiebinger – and the 20th century, with chapters on writings associated with Marie Curie (Vita Fortunati), the interweaving lives and writings of mid-century anthropology (Franceschi), and late-century biosciences (Keller and Abir-Am). This is not the place to find an historical overview of the roles of biography or gender in science, although the formational historiography is well covered.

While certain figures – Bassi, Curie, Barbara McClintock – receive repeated and sustained attention, the chapters reveal a range of de-centring strategies that have been adopted to avoid the perceived pitfalls of biography. Several show that looking at comparative or interlocking lives can help us to reflect better on the meaning of each, and on their relevance to and within the wider context. Cavazza writes of the “metabiographies” (p. 69) of Bassi, which do more to reveal contemporary views of gender than the women herself, while Findlen discusses the use of “eccentric biography” (p. 115). Govoni uses group biography to establish fuller networks of influence than those revealed in the autobiography of the writer Italo Calvino, while Franceschi considers genealogies of lives and life-writings, to which Abir-Am adds “ego-histoire” (p. 226) when considering women of her own generation and its impact (or lack of impact) on those that followed. On the evidence here, Mazzotti is surely right to see biography not in opposition to social and cultural studies of science but as “one of the most effective ways to explore how cognitive and social structures are constructed, sustained, and modified” (p. 136).

There is much to enjoy in this book even for those who do not have a direct interest in biography, gender or the individuals discussed. The passion of several of the authors for their work and broader mission – less often, tellingly, for their subjects – comes over clearly in their chapters. There are also some lovely stories that reveal the historian’s world and craft, with memories of career-defining finds in card catalogues, discussions with archivists and the support of partners and colleagues. Most salutary, however, is the reminder of just how difficult it was for women to forge careers in academia, not just in the 18th century but also in the late 20th. While it is clear that biographies are not today written by professional historians to provide aspirational role models, these essays demonstrate the overwhelming significance of networks, mentors, family and supporters to forging and understanding lives in science.

]]>I am looking particularly for copies of the medal that were made from the original die that was engraved by John Sigismund Tanner at the Royal Mint (his signature ‘T’ is visible on Athena/Minerva’s plinth). One of the very earliest is that given to John Belchier (below, now at the British Museum) – it was awarded in 1737 but he only received the medal after copies were first struck in 1742.

As far as I can tell, this original die was used throughout the 18th and 19th century. Every dozen or so years a fresh batch of medals was struck and then handed out annually until they ran out. By the early 20th century a new die had been produced – this was used for the medals given to Joseph Lister (1902) and Dimitri Mendeleev (1905, below – I think now at the Russian Academy of Sciences). If you compare the images you can see that the face of the figure has changed and the handle on the air pump is straight rather than curly.

I do not yet know just when the die was re-engraved, or who was responsible, although the obverse is now signed TM. The medal changed again substantially in the 20th century, with a new die designed by Mary Gillick, dates 1944 (below, Royal Society). Gillick, also responsible for the young Queen Elizabeth II on British coins 1953-70, dispatched Athena and brought in a portrait of Godfrey Copley.

So far, for the medals awarded between 1737 and 1901, I have only tracked down eight [Edit: this number will increase as I find more – I have 11 as of 11/11/16]. There must be many more out there and I’d love to know of any in private or public collections.

Those I know about, all from the original die, are:

1737, John Belchier, British Museum M.8316

1747, Gowin Knight, British Museum

1752, John Pringle, Royal Society M/132

1770, William Hamilton, British Museum (from Sophia Banks Collection)

1772, Joseph Priestley, Royal Society M/112

1775, Nevil Maskelyne, National Maritime Museum ZBA2361

1776, James Cook, British Museum M.4833

1818, Robert Seppings, National Maritime Museum MED1003

1831, George Biddell Airy, National Maritime Museum MED2122

1858, Charles Lyell, Royal Society M/167

1883, William Thomson, The Hunterian (Glasgow) GLAHM:C.1916.13

I also know of engravings of the 1753 medal given to Benjamin Franklin (in the Gentleman’s Magazine), and the 1750 medal given to George Edwards (on the title page of his Natural History of Uncommon Birds). In addition, the medal given to Edward Sabine in 1821 was sold a couple of years ago, but I don’t know where it ended up.

The complete list of Copley Medallists can be found on Wikipedia. Can anyone help me track down any other extant Copley Medals of the 18th and 19th centuries?

]]>Readers of this blog will be particularly interested in the funding available for the MA in History of Science, Medicine, Environment and Technology or MSc in Science, Society and Communication. As well as a dedicated £5000 scholarship students for the former can also apply for the full scholarship for MA study within the School.

Those interested in PhD-level research have several schemes to choose from. There are full scholarships via the AHRC consortium of which Kent is part (CHASE) and the University (Vice Chancellor’s Research Scholarships), and up to 20 (ranging from full to fees-only) focused on selected broad themes suiting the wide range of interests among the School’s staff. In particular, note the one on the History of Scientific Visualisation, open to any project fitting the theme and any period between 1700-2000, to be undertaken with my colleague Omar Nasim. (Depending on the topic, either I or Charlotte Sleigh might second supervise.) Full details are copied below.

Do add comments here or email if you have any questions – I am Director of Postgraduate Recruitment and Admissions for the School. The deadline for CHASE scholarships is 13 January 2016, for VC and School PhD Scholarships is 31 January and 13 March for Masters’ funding.

‘The History of Scientific Visualization, ca. 1700-2000’

The theme is writ large so as include all sorts of possible projects within its scope. But of particular interest are those proposals will sync well with the diverse interests of the members of SMET. As such, the project selected will follow along these broad lines: (1) a study that pays attention to the roles played in the history of science of a particular medium or a range of media (digital, pencil and paper, photography, engraving, or plaster models, etc.). This should be linked to (2) a sensitivity for techniques, practices and methods in the use of media, especially as they connect to specific kinds of scientific activities, such as observing, experimenting, communicating, displaying, instructing, and so on. (3) The scientific practices associated with visualization should also be embedded into cultural and intellectual, institutional and social contexts. Welcome are projects that extend possible contexts into the non-Western or global history contexts as well, so as to challenge the present state-of-the-art in the field and look at ways in which images might be produced, reproduced, and received within a variety of cultures, societies, or nations. And finally, (4) there is a preference for projects that are strongly interdisciplinary.

Directions:

a) Connecting the history of scientific visualization to reception, consumption, and production across disciplinary and national boundaries.

b) The impact that culturally embedded practices of visualization had not just on the history of sciences but also in the arts of a given period.

c) The ways in which the presentation of scientific images relates to their production will be a major direction to be taken.

d) The power of the images in science for society and commerce is also something to be taken seriously. The ways in which such images shape how science is viewed but also used by non-scientific actors.

For further information please contact Dr Omar Nasim.

This post is an appendix, where I can show more of the eclipse maps published than I could on the Guardian’s website. I should add, too, that these were not the first predictions or maps of solar eclipses, and that there were earlier German, Dutch and French maps.

Here, however, is Halley’s first map, from Eclipse Maps, which was published in advance of the event, encouraging observation. It is titled “A Description of the Passage of the Shadow of the Moon over England, In the Total Eclipse of the Sun, on the 22d Day of April 1715 in the Morning”. I am not sure where the original is kept, but it may be the same as that reproduced in black and white in Jay Pasachoff’s article on Halley’s eclipse maps, which is from the Houghton Library. The full text, which is not high enough resolution to read here, has been transcribed by Pasachoff.

Halley seems to have produced more than one edition of the map before 22 April 1715 (O.S. – the anniversary was celebrated on 3 May N.S.), and also one after the event, showing the path as corrected by observations. This copy of his “A Description of the Passage of the Shadow of the Moon over England as it was Observed in the late Total Eclipse of the Sun April 22d, 1715 Manè” is from the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, where you can see some superbly high-resolution images.

Halley came back to his winning formula when another eclipse rolled along. His map, published in 1723 (annotated November 17123 here), showed both the recomputed path of the 1715 eclipse and the predicted path of 11 May 1724. This image is from the Houghton Library’s Tumblr, where it is available in higher resolution. The text declares that the first map “has had the desired effect” in encouraging observation and uses this one to demonstrate that his predictions had been pretty good in 1715 and were worth acting on again.

However, as my post discussed, William Whiston was also in the business of predicting eclipses and selling scientific paraphernalia. Like Halley, he was making predictions based on John Flamsteed’s observations at the Royal Observatory and corrected with Isaac Newton’s theory, and encouraging observations. Whiston made comparison of his observations with Halley’s and his two eclipse-predicting broadsheets are again from the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy’s Library here and here.

The one I think is the earlier from Whiston was dated 2 April 1715 and titled “A Compleat Account of the great Eclipse of the Sun which will happen Apr. 22 in the Morning”. It is much more text-heavy and technical in content, and the map is a celestial one, showing the positions of the heavenly bodies rather than the path of the shadow on Earth.

A second broadsheet by Whiston did show the Sun’s shadow on the Earth, but from a global point of view. The title too emphasised that this was not just an English matter: “A Calculation of the Great Eclipse of the Run, April 22d 1715 in ye Morning, from Mr Flamsteed’s Tables; as corrected according to Sr Isaac Newton’s Theory of ye Moon in ye Astronomical Lectures; with its Construction for London Rome and Stockholme”. It also advertised an instrument that could be bought from Whiston.

John Westfall and William Sheehan’s new book on observing eclipses, transits and occultations, indicates the Whiston and Halley’s estimates varied by about 25 miles, which perhaps puts the more triumphant claims of accuracy in perspective. I think (correct me below if I am wrong) that Halley’s prediction was the more accurate, but there was an element of luck involved. Above all, his map, showing geographical detail of England beneath the path of totality, was much more persuasive and appealing – this is the main reason that the 1715 eclipse became ‘Halley’s’.

Whiston had learned the importance of the image by 1724. His “The Transit of the Total Shadow of the Moon” this time showed familiar coastal outlines, although again other parts of Europe were included: Paris would be a better observing site than London this time. This version is from the Science & Society Picture Library and belongs to the Royal Astronomical Society.

And so the maps continued: there are many to explore in the wonderful albums at Eclipse Maps. It was a flourishing business come eclipses in the 1730s and beyond, especially that of 1764, as many publishers jumped on the opportunity that Halley and Whiston had spotted in 1715. So too, of course, had the person that links all the images shown here: the engraver and cartographer John Senex, who deserves a much fuller biography on Wikipedia than this!

]]>

There were, however, more than a few staff and visitors who were annoyed that we were mixing fact and fiction and taking away the authoritative voice of the Museum. How would people learn anything? How would they know what was real history and which were the real objects? Either proving or entirely dismissing their point, most visitors, particularly tourists there for a photograph on the prime meridian, probably didn’t even realise that they were not seeing a straight forward exhibition.

What those who worried about ‘reality’ perhaps don’t fully appreciate is the extent to which fictions and fakes are always a part of museum displays. It is the joy of something like this exhibition – or the really wonderful Stranger than Fiction exhibition at the Science Museum – that they force you to think harder about what we’re presented with and how we too blindly trust the authority and ‘reality’ of certain modes of presentation.

For me, this photograph I took in the Royal Observatory’s Octagon Room during Longitude Punk’d nicely brings out some of what I mean.

While, even for the non-too eagle-eyed, it is clear that the dress in the centre, created for Longitude Punk’d, is not 18th century, for most visitors it might appear that this is a modern piece, with historical nods, simply dropped into a 17th-century space. It is a fiction dropped into history. But things are not what they seem.

Firstly, of course, we can note the museological trappings that make this space very different to the one that John Flamsteed knew. There are barriers, electric lights and museum labels, also a smooth, light wood floor. But what of those paintings? The instruments? The clocks and panelling?

A right old mix-up is the answer. Artfully arranged to evoke the 1676 engraving of the room by Francis Place:

![Prospectus intra Cameram Stellatam [View inside the Star Room] (Photo: National Maritime Museum)](https://teleskopos.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/octagon-room.jpg?w=645)

The astronomical quadrant, on the left, is a ‘real’ historic object, but some 75 years too late for this set-up. The telescope on the right (out of sight in my picture, but recreating the one in the engraving) is pure prop, without lenses. It used to offer those who bothered to take a look a view of a faded slide of Pluto (the cartoon dog). Now, after much effort of the sort that only those acquainted with the pace of change in large museums will appreciate, it has a picture of Saturn (the planet), fuzzed and chromatically distorted to give some sort of idea of what it was like looking through an early telescope. Obviously Saturn ain’t really visible, through the windows, in the daylight.

What of the paintings? Well, the rather splendid portrait of Charles II (left) is from 1670. I assume (correct me if I’m wrong – annoyingly the catalogue entry doesn’t give the provenance) that this has stayed at Greenwich, if not this room, throughout the centuries – it is certainly similar to the one in the engraving. However, for the purposes of this post we should note that it is nevertheless “thought to be a copy of a Lely”.

The engraving also shows us a painting of the Duke of York, later James II, who had been, perhaps significantly, Lord High Admiral until 1673. However, the one that is currently there is in fact a commissioned replica from 1984. I have no idea what happened to the (copy?) Lely of James that was originally there. Did Charles survive and not James because of an anti-Catholic Astronomer Royal (nearly all of them, I reckon, before the 20th century)? Answers below, please.

The clocks, originally by Thomas Tompion, are perhaps the most complex story of all. Again, what’s in the two images appears to match but that’s about where it stops. Famously, after Flamsteed’s death his wife Margaret sold off the books and instruments at the Observatory, fairly seeing them as private property since they had either been bought by or gifted to Flamsteed. The clocks, therefore, left the observatory.

Today, one of the clocks is back, but on the other side of the room. That is because it was altered and its original 13-foot pendulum changed so that it could be turned into a longcase clock. The clock, with the original dial fitted into an 18th-century wooden case and its mechanism on display in a late 20th-century glass case, is a completely different beast. Next to it is a (wonderful) interloper: a Tompion longcase, which only moved to the Observatory in 2010.

What you can see in the top picture is two replica dials (although the one on the far right is a replica of a sideral clock that, although it was included in the Place drawing, seems never to have actually been installed at the Observatory: a replica of a fiction, therefore) and a reconstruction. The reconstruction, a “tribute” to Tompion by a horology student at West Dean College, has a transparent dial so that the extraordinary pendulum, with a backwards-and-forwards rather than side-to-side motion, can be admired. Excitingly, though, for seekers of ‘reality’, the clock’s positioning was “made possible as many of the original holes for the mount fittings are still visible.”

There we have it. The most original thing in the room are some holes behind the skirting.

]]>